Chapter 7

Using Mindfulness for Yourself and Others

In This Chapter

![]() Discovering a short mindful exercise you can use anywhere

Discovering a short mindful exercise you can use anywhere

![]() Finding mindful ways of taking care of yourself

Finding mindful ways of taking care of yourself

![]() Applying mindfulness in relationships

Applying mindfulness in relationships

You require a lot of looking after. You need to eat a balanced diet and exercise regularly to maintain optimum health and wellbeing. You need to have the right amount of work and rest in your life. And you need to challenge yourself intellectually, to keep your mind healthy. You need to socialise and also save some time just for yourself. Achieving all this perfectly is impossible, but how can you strive to take care of yourself in a light-hearted way, without becoming overly uptight and stressed?

Mindfulness can help you look after both yourself and others. Being aware of your thoughts, emotions and body, as well as the things and people around you, is the starting point. This awareness enables you to become sensitive to your own needs and those of others around you, therefore encouraging you to meet everyone’s needs as far as possible.

A caring, accepting awareness is the key to healthy living. Mindfulness is a wonderful way to develop greater awareness. This chapter details suggestions for looking after yourself and others through mindfulness.

Using a Mini Mindful Exercise

You don’t need to practise mindfulness meditation for hours and hours to reap its benefits. Short and frequent meditations are an effective way of developing mindfulness in your everyday life.

Introducing the breathing space

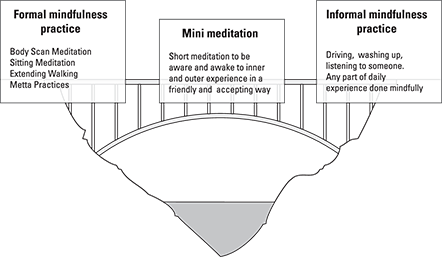

When you’ve had a busy day, you probably enjoy stopping for a nice hot cup of tea or coffee, or another favourite beverage. The drink offers more than just liquid for the body. The break gives you a chance to relax and unwind a bit. The three-minute mini meditation, called the breathing space (illustrated in Figure 7-1 and 7-2), is a bit like a tea break, but beyond relaxation, the breathing space enables you to check what’s going on in your body, mind, and heart – not getting rid of feelings or thoughts, but looking at them from a clearer perspective.

Practising the breathing space

You can practise the breathing space at almost any time and anywhere. The meditation is made up of three distinct stages, which I call A, B, and C to help you to remember what to practise at each stage. The exercise doesn’t have to last exactly three minutes: you can make it longer or shorter depending on where you are and how much time you have. If you only have time to feel three breaths, that’s okay; doing so can still have a profound effect. Follow these steps, which are available as an audio track (Track 17):

Sit upright with a sense of dignity, but don’t strain your back and neck. If you can’t sit upright, try standing; even lying down on your back or curling up is acceptable. Sitting upright is helpful, because it sends a positive message to the brain – you’re doing something different.

Sit upright with a sense of dignity, but don’t strain your back and neck. If you can’t sit upright, try standing; even lying down on your back or curling up is acceptable. Sitting upright is helpful, because it sends a positive message to the brain – you’re doing something different.

Figure 7-1: How the breathing space acts as a bridge between formal and informal mindfulness practice.

- Practise step A below for about a minute or so, then move on to B for a minute, ending with C also for a minute – or however long you can manage:

Step A: Awareness:

Reflect on the following questions, pausing for a few seconds between each one:

- What bodily sensations am I aware of at the moment? Feel your posture, become aware of any aches or pains, or any pleasant sensations. Just accept them as they are, as far as you can.

- What emotions am I aware of at the moment? Notice the feelings in your heart or belly area or wherever you can feel emotion.

- What thoughts am I aware of, passing through my mind at the moment? Become aware of your thoughts, and the space between yourself and your thoughts. If you can, simply observe your thoughts rather than becoming caught up in them.

Step B: Breathing:

Focus your attention in your belly area – the lower abdomen. As best you can, feel the whole of your in-breath and the whole of each out-breath. You don’t need to change the rate of your breathing – just become mindful of it in a warm, curious and friendly way. Notice how each breath is slightly different. If your mind wanders away, gently and kindly guide your attention back to your breath. Appreciate how precious each breath is.

Step C: Consciously expanding:

Consciously expand your awareness from your belly to your whole body. Get a sense of your entire body breathing (which it is, through the skin). As our awareness heightens within your body, notice its effect. Accept yourself as perfect and complete just as you are, just in this moment, as much as you can.

The breathing space meditation encapsulates the core of mindfulness in a succinct and portable way. The full effects of the breathing space are:

- You move into a restful ‘being’ mode of mind. Your mind can be in one of two very different states of mind: doing mode or being mode. Doing mode is energetic and all about carrying out actions and changing things. Being mode is a soothing state of mind where you acknowledge things as they are. (For lots more on being and doing mode, refer to Chapter 5.)

- Your self-awareness increases. You become more aware of how your body feels, the thoughts going through your mind, and the emotion or need of the moment. You may notice that your shoulders are hunched or your jaw is clenched. You may have thoughts whizzing through your head that you hadn’t even realised were there. Or perhaps you’re feeling sad, or are thirsty or tired. If you listen to these messages, you can take appropriate action. Without self-awareness, you can’t tackle them.

- Your self-compassion increases. You allow yourself the space to be kinder to yourself, rather than self-critical or overly demanding. If you’ve had a tough day, the breathing space offers you time to let go of your concerns, forgive your mistakes and come back into the present moment. And with greater self-compassion, you’re better able to be compassionate and understanding of others too.

- You create more opportunities to make choices. You make choices all the time. At the moment, you’ve chosen to read this book and this page. Later on you may choose to go for a walk, call a friend, or cook dinner. If your partner snaps at you, your reaction is a choice to a certain extent too. By practising the breathing space, you stand back from your experiences and see the bigger picture of the situation you’re in. When a difficulty arises, you can make a decision from your whole wealth of knowledge and experience, rather than just having a fleeting reaction. The breathing space can help you make wiser decisions.

- You switch off automatic pilot. Have you ever eaten a whole meal and realised that you didn’t actually taste it? You were most likely on automatic pilot. You’re so used to eating, you can do it while thinking about other things. The breathing space helps to connect you with your senses so that you’re alive to the moment.

Try this thought experiment. Without looking, remember whether your wrist watch has roman numerals or normal numbers on it. If you’re not sure, or get it wrong, it’s a small indication of how you’re operating on automatic pilot. You’ve looked at your watch hundreds of times, but not really looked carefully. (I explain more about automatic pilot in Chapter 5.)

- You become an observer of your experience rather than feeling trapped by it. In your normal everyday experience, no distance exists between you and your thoughts or emotions. They just arise and you act on them almost without noticing. One of the key outcomes of the breathing space is the creation of a space between you and your inner world. Your thoughts and emotions can be in complete turmoil, but you simply observe and are free from them, like watching a film at the cinema. This seemingly small shift in viewpoint has huge implications, which I explore in Chapter 5.

- You see things from a different perspective. Have you ever taken a comment too personally? I certainly have. Someone is critical about a piece of work I’ve done, and I immediately react or at least feel a surge of emotion in the pit of my stomach. But you have other ways of reacting. Was the other person stressed out? Are you making a big deal about nothing? The pause offered by the breathing space can help you see things in another way.

- You walk the bridge between formal and informal practice. Formal practice is where you carve out a chunk of time in the day to practise meditation. Informal practice is being mindful of your normal everyday activities. The breathing space is a very useful way of bridging the gap between these two important aspects of mindfulness. The breathing space is both a formal practice because you’re making some time to carry it out, and informal because you integrate it into your day-to-day activities.

- You create a space for new ideas to arise. By stopping your normal everyday activities to practise the breathing space, you create room in your mind for other things to pop in. If your mind is cluttered, you can’t think clearly. The breathing space may be just what the doctor ordered to allow an intelligent insight or creative idea to pop into your mind.

Figure 7-2: The three-minute breathing space meditation progresses like an hourglass.

Using the breathing space between activities

Aim to practise the breathing space three times a day. Here are some suggested times for practising the breathing space:

- Before or after meal times. Some people pray with their family before eating a meal to be together with gratitude and give thanks for the food. Doing a breathing space before or after a meal gives you a set time to practise and reminds you to appreciate your meal too. If you can’t manage three minutes, just feel three breaths before diving in.

- Between activities. Resting between your daily activities, even for just a few moments, is very nourishing. Feeling your breath and renewing yourself is very pleasant. Research has found that just three mindful breaths can change your body’s physiology, lowering blood pressure and reducing muscle tension.

- On waking up or before going to bed. A short meditation before you jump out of bed can be a wholesome experience. You can stay lying in bed and enjoy your breathing. Or you can sit up and do the breathing space. Meditating in this way helps to put you in a good frame of mind and sets you up for meeting life afresh. Practising the breathing space before going to bed can calm your mind and encourage a deeper and more restful sleep.

- When a difficult thought or emotion arises. The breathing space meditation is particularly helpful when you’re experiencing challenging thoughts or emotions. By becoming aware of the nature of your thoughts, and listening to them with a sense of kindness and curiosity, you change your relationship to them. A mindful relationship to thoughts and emotions results in a totally different experience.

Using Mindfulness to Look After Yourself

Have you ever heard the safety announcements on a plane? In the event of an emergency, cabin crew advise you to put your own oxygen mask on first, before you help put one on anyone else, even your own child. The reason is obvious. If you can’t breathe yourself, how can you possibly help anyone else? Looking after yourself isn’t just necessary in emergencies. In normal everyday life, you need to look after your own needs. If you don’t, not only do you suffer, but so do all the people who interact or depend on you. Taking care of yourself isn’t selfish: it’s the best way to be of optimal service to others. Eating, sleeping, exercising, and meditating regularly are all ways of looking after yourself and hence others.

Exercising mindfully

You can practise mindfulness and do physical exercise at the same time. In fact, Jon Kabat-Zinn, one of the key founders of mindfulness in the West, trained the USA men’s Olympic rowing team in 1984. A couple of the men won gold – not bad for a bunch of meditators! And in the more recent 2012 Olympics in London, several athletes claimed that meditation helped them to reach peak performance and achieve their gold medals.

To start you off, here are a few typical physical exercises and ideas for how to suffuse them with mindfulness.

Mindful running

Leave the portable music player and headphones at home. Try running outside rather than at the gym – your senses have more to connect with outside. Begin by taking ten mindful breaths as you walk along. Become aware of your body as a whole. Build up from normal walking to walking fast to running. Notice how quickly your breathing rate changes, and focus on your breathing whenever your mind wanders away from the present moment. Feel your heart beating and the rhythm of your feet bouncing on the ground. Notice whether you’re tensing up any parts of your body unnecessarily. Enjoy the wind against your face and the warmth of your body. Observe what sort of thoughts pop up when you’re running, without being judgemental of them. If running begins to be painful, explore whether you need to keep going or slow down. If you’re a regular runner, you may want to stay on the edge a little bit longer; if you’re new to it, slow down and build up more gradually. At the end of your run, notice how you feel. Try doing a mini meditation (described in the first section of this chapter) and notice its effect. Keep observing the effects of your run over the next few hours.

Mindful swimming

Begin with some mindful breathing as you approach the pool. Notice the effect of the water on your body as you enter. What sort of thoughts arise? As you begin to swim, feel the contact between your arms and legs and the water. What does the water feel like? Be grateful that you can swim and have access to the water. Allow yourself to get into the rhythm of swimming. Become aware of your heartbeat, breath rate, and the muscles in your body. When you’ve finished, observe how your body and mind feel.

Mindful cycling

Begin with some mindful breathing as you sit on your bike. Feel the weight of your body, the contact between your hands and the handlebars, and your foot on the pedal. As you begin cycling, listen to the sound of the wind. Notice how your leg muscles work together rapidly as you move. Switch between focusing on a specific part of your body like the hands or face to a wide and spacious awareness of your body as a whole. Let go of wherever you’re heading and come back to the here and now. As you get off your bike, perceive the sensations in your body. Scan through your body and detect how you feel after that exercise.

Preparing for sleep with mindfulness

Sleep, essential to your wellbeing, is one of the first things to improve when people do a course in mindfulness. People sleep better, and their sleep is deeper. Studies found similar results from people who suffered from insomnia who did an eight-week course in MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction).

Sleep is about completely letting go of the world. Falling asleep isn’t something you do – it’s about non-doing. In that sense sleep is similar to mindfulness. If you’re trying to sleep, you’re putting in a certain effort, which is the opposite of letting go.

Here are some tips for preparing to sleep using mindfulness:

- Stick to a regular time to go to bed and to wake up. Waking up very early one day and very late the next confuses your body clock and may cause difficulties in sleeping.

- Avoid over-stimulating yourself by watching television or being on the computer before bed. The light from the screen tricks your brain into believing it’s still daytime, and then it takes longer for you to fall asleep.

- Try doing some formal mindfulness practice like a sitting meditation or the body scan (refer to Chapter 6) before going to bed.

- Try doing some yoga or gentle stretching before going to bed. I’ve noticed cats naturally stretch before curling up on the sofa for a snooze. This may help you to relax and your muscles unwind. Try purring while you’re stretching, too – maybe that’s the secret to their relaxed way of life!

- Do some mindful walking indoors before bed. Take five or ten minutes to walk a few steps and feel all the sensations in your body as you do so. The slower, the better.

- When you lie in bed, feel your in-breath and out-breath. Rather than trying to sleep, just be with your breathing. Count your out-breaths from one to ten. Each time you breathe out, say the number to yourself. Every time your mind wanders off, begin again at one.

- If you’re lying in bed worrying, perhaps even about getting to sleep, accept your worries. Challenging or fighting thoughts just makes them more powerful. Note them, and gently come back to the feeling of the breath.

Looking at a mindful work–life balance

Work–life balance means balancing work and career ambitions on the one side, and home, family, leisure and spiritual pursuits on the other. Working too much can have a negative impact on other important areas. By keeping things in balance, you’re able to get your work done quicker and your relationship quality tends to improve.

With the advent of mobile technology, or a demanding career, work may be taking over your free time. And sometimes you may struggle to see how you can re-dress this imbalance. The mindful reflection below may help.

- Sit in a comfortable upright posture, with a sense of dignity and stability.

- Become aware of your body as a whole, with all its various changing sensations.

- Guide your attention to the ebb and flow of your breath. Allow your mind to settle on the feeling of the breath.

- Observe the balance of the breath. Notice how your in-breath naturally stops when it needs to, as does the out-breath. You don’t need to do anything – it just happens. Enjoy the flow of the breath.

- When you’re ready, reflect on this question for a few minutes:

What can I do to find a wiser and healthier balance in my life?

- Go back to the sensations of the breathing. See what ideas arise. No need to force any ideas. Just reflect on the question gently, and see what happens. You may get a new thought, image or perhaps a feeling.

- When you’re ready, bring the meditation to a close and jot down any ideas that may have arisen.

Refer to Work/Life Balance For Dummies by Katherine Lockett and Jeni Mumford (Wiley) for more on this topic.

Using Mindfulness in Relationships

Humans are social animals. People’s brains are wired that way. Research into positive psychology, the new science of wellbeing, shows that healthy relationships affect happiness more than anything else does. Psychologists have found that wellbeing isn’t so much about the quantity of relationships but the quality. You can directly develop and enhance the quality of your relationships through mindfulness.

Starting with your relationship with yourself

Trees need to withstand powerful storms, and the only way they can do that is by having deep roots for stability. With shallow roots, the tree can’t really stand upright. The deeper and stronger the roots, the bigger and more plentiful are the branches that the tree can produce. In the same way, you need to nourish your relationship with yourself to effectively branch out to relate to others in a meaningful and fulfilling way.

Here are some tips to help you begin building a better relationship with yourself by using a mindful attitude:

- Set the intention. Begin with a clear intention to begin to love and care for yourself. You’re not being selfish by looking after yourself; you’re watering your own roots, so you can help others when the time is right. You’re opening the door to a brighter future that you truly deserve as a human being.

- Understand that no one’s perfect. You may have high expectations of yourself. Try to let them go, just a tiny bit. Try to accept at least one aspect of yourself that you don’t like, if you can. The smallest of steps make a huge difference. Just as a snowball starts small and gradually grows as you roll it through the snow, so a little bit of kindness and acceptance of the way things are can start off a positive chain reaction to improve things for you.

- Step back from self-criticism. As you practise mindfulness, you become more aware of your thoughts. You may be surprised to hear a harsh, self-critical inner voice berating you. Take a step back from that voice if you can, and know that you’re not your thoughts. When you begin to see this, the thoughts lose their sting and power. (The sitting meditation in Chapter 6 explores this.)

- Be kind to yourself. Take note of your positive qualities, no matter how small and insignificant they seem, and acknowledge them. Maybe you’re polite, or a particular part of your body is attractive. Or perhaps you’re generous or a good listener. Whatever your positive qualities are, notice them rather than looking for the negative aspects of yourself or what you can’t do. Being kind to yourself isn’t easy, but through mindfulness and by taking a step-by-step approach, it’s definitely possible.

- Forgive yourself. Remember that you’re not perfect. You make mistakes, and so do I. Making mistakes makes us human. By understanding that you can’t be perfect in what you do, and can’t get everything right, you’re more able to forgive yourself and move on. Ultimately, you can learn only through making mistakes: if you did everything correctly, you’d have little to discover about yourself. Give yourself permission to forgive yourself.

- Be grateful. Develop an attitude of gratitude. Try being grateful for all that you do have, and all that you can do. Can you see, hear, smell, taste, and touch? Can you think, feel, walk, and run? Do you have access to food, shelter, and clothing? Use mindfulness to become more aware of what you have. Every evening before going to bed, write down three things that you’re grateful for, even if they’re really small and insignificant. Writing gratitude statements each evening has been proven to be beneficial for many people. Try this for a month, and continue if you find the exercise helps you in any way.

- Practise metta/loving kindness meditation. This is probably the most effective and powerful way of developing a deeper, kinder, and more fulfilling relationship with yourself. Refer to Chapter 6 for the stages of the metta practice.

Dealing with arguments in romantic relationships: A mindful way to greater peace

Arguments are often the cause of many difficult interactions with others, especially in romantic relationships. Romantic relationships can be both deeply satisfying and deeply painful. And they’re most difficult when disagreements arise. Sometimes (or often) those disagreements turn into arguments. Here’s a typical scenario:

- A: Why do you keep leaving your clothes lying on the floor in the bedroom? It looks so messy!

- B: Why are you so picky! Relax, will you. It’s not a big deal. You’re always nagging about everything.

- A: Me, nagging! Who’s been doing all the cooking today? And all I ask is for you to pick up a few clothes, and that’s too much effort. You’re so childish.

- B: Childish! Listen to yourself shouting about some clothes …

And so on. Your higher brain function becomes unavailable when you get into an argumentative state of mind. The frustration and emotional reactivity build with each sentence that each person says.

So, how on earth can mindfulness help when these small things start to escalate into a full-blown argument and a negative atmosphere? Mindfulness creates a mental and emotional inner space – some space between the moment when you feel your irritation rising and your decision to speak. In that space, you have time to make a choice about what to say.

If your partner accuses you of leaving clothes on the floor, you notice yourself getting defensive. But in that extra space you have, you can also think about your partner: he’s had a long day, is tired and has a bit of a short fuse. From that understanding, you’re able to say a few kind words or offer a little hug or massage. The situation begins to defuse itself.

That all-important few seconds between your emotional experience and your choice of words is created through mindfulness practice. As you become adept in mindfulness, you become less automatically reactive. You’re conscious of what’s happening within you and can make these better decisions.

Here’s how to deal with potential arguments:

Notice the emotion rising up in your body when your partner says something that hurts you.

Notice the emotion rising up in your body when your partner says something that hurts you.- Become aware of where you feel the emotion in your body and take a few breaths. Be as kind and friendly to yourself as you can. Say to yourself, ‘This emotion is difficult for me to feel right now … Let me gently breathe with it.’

- Choose the words you respond with wisely from your more mindful state of mind. Perhaps begin with agreeing with part of your partner’s statement. Soften your tone of voice. Let your partner know how you feel, if you can. And avoid making accusations – doing so will just feed the argument.

- As you begin to calm down, try to be more and more mindful. Keep feeling your breathing. Or be conscious of your bodily sensations or other emotions. Gently smile if you can. This approach will make you less reactive and more likely to shift the conversation into more positive territory.

Engaging in deep listening

Deep or mindful listening occurs when you listen with more than your ears. Deep listening involves listening with your mind and heart – your whole being. You’re giving completely when you engage in deep listening. You let go of all your thoughts, ideas, opinions, and beliefs and just listen.

Deep listening comes from an inner calm. If your mind is wild, it’s very difficult for you to listen properly. If your mind is in turmoil, go away to listen to your breathing or even to your own thoughts. By doing so, you give your thoughts space to arise out of the unconscious, and you thereby release them.

Here’s how to listen to someone deeply and mindfully:

- Stop doing anything else. Set your intention to listen deeply.

- Look the person in the eye when he speaks and gently smile, if appropriate.

- Put aside all your own concerns and worries.

- Listen to what the person is saying and how he’s saying it.

- Listen with your whole being – your mind and heart, not just your head.

- Observe posture and tone of voice as part of the listening process.

- Notice the automatic thoughts popping into your head as you listen. Do your best to let them go and come back to listening.

- Ask questions if necessary, but keep them genuine and open rather than trying to change the subject. Let your questions gently deepen the conversation.

- Let go of judgement as far as you can. Judging is thinking rather than deep listening.

- Let go of trying to solve the problem or giving the person the answer.

When you give the other person the space and time to speak without judging, he begins to listen to himself. What he’s saying becomes very clear to him. Then, quite often, the solution arises naturally. He knows himself far better than you do. By jumping straight into solutions, you only reduce the opportunity that person has to communicate with you. So, when listening, simply listen.

Being aware of expectations

Think about the last time someone annoyed you. What were your expectations of that person? What did you want him to say or do? If you have excessively high expectations in your relationships, you’re going to find yourself frustrated.

Expectations are ideals created in your mind. The expectations are like rules. I expect you to behave; or to be quiet; or to make dinner every evening; or to be funny, not angry or assertive. The list is endless.

I aim to have low rather than high expectations with friends and family. I don’t expect any presents on birthdays or any favours to be returned. I don’t expect people to turn up to meetings on time or to return phone calls. This way, I’m not often disappointed. In fact, I’m pleasantly surprised when a friend does call me, does a favour for me or is kind to me! I feel very fortunate to have lovely friends and family who are supportive and fun to be with. But if I had very high expectations, I’d be setting myself up for disappointment. With reduced expectations, you set the stage for greater gratitude and positivity in your relationships when others do reach out.

- Don’t speak yet. A negative reaction just fuels the fire.

- Become aware of your breathing without changing it. Is it deep or shallow? Is it slow or rapid? If you can’t feel it, just count the out-breaths from one to ten. Or just to three if that’s all you have time for.

- Notice the sensations in your body. Do you feel the pain of the unfulfilled expectation in your stomach, shoulders, or somewhere else? Does it have a shape or colour?

- Imagine or feel the breath going into that part of the body. Feel it with a sense of kindness and curiosity. Breathe into it and see what happens.

- Take a step back. Become aware of the space between you, the observer, and your thoughts and feelings, which are the observed. See how you’re separate and therefore free of them. You’re going into observer mode, taking a step back, having a bird’s-eye view of the whole situation from a bigger perspective.

- If necessary, go back to that person and speak from this wiser and more composed state of mind. Don’t speak unless you’re settled and calm. Most of the time, speaking in anger may get what you want in the short term, but in the long term you leave people feeling upset. Play this by ear.

Looking into the mirror of relationships

Relationship is a mirror in which you can see yourself.

J Krishnamurti

All relationships, whether with a partner or work colleague, are a mirror that help you to see your own desires, judgements, expectations, and attachments. Relationships give an insight into your own inner world. What a great learning opportunity! You can think of relationships as an extension of your mindfulness practice. You can observe what’s happening, both in yourself and the other person, with a sense of friendly openness, with kindness and curiosity. Try to let go of what you want out of the relationship, just as you do in meditation. Let the relationship simply be as it is, and allow it to unfold moment by moment.

Here are some questions to ask yourself as you observe the mirror of relationships:

- Behaviour. How do you behave in different relationships? What sort of language do you use? What’s your tone of voice like? Do you always use the same words or sentences? What happens if you speak less, or more? Notice your body language.

- Emotions. How do you feel in different relationships? Do certain people or topics create fear or anger or sadness? Get in touch with your emotions when you’re with other people, and see what the effect is. Try not to judge the emotions as good or bad, right or wrong: just see what they do.

- Thoughts. What sort of thoughts arise in different relationships? What happens if you observe the thoughts as just thoughts and not facts? How are your thoughts affected by how you feel? How do your thoughts affect the relationship?

Being mindful in a relationship is more difficult than it sounds. You can easily find yourself caught up in the moment and your attention is trapped. Through regular mindfulness practice, your awareness gradually increases and becomes easier. Although mindfulness in relationships is challenging, it’s very rewarding too.

Working with your emotions

‘You make me angry.’ ‘You’re annoying me.’ ‘You’re stressing me out.’

If you find yourself thinking or saying sentences like these, you’re not really taking responsibility for your own emotions. You’re blaming someone else for the way you feel. This may seem perfectly natural. However, in truth, no one can affect the way you feel. The way you feel is determined by what you think about the situation. For example, say I accidentally spill a cup of tea on your work. If you think that I did it on purpose, you may think, ‘You damaged my paperwork deliberately, you idiot,’ and then feel angry and upset. You blame me for your anger. If you see it as an accident and think that I may be tired, you think, ‘It was just an accident – I hope he’s okay,’ and react with sympathy. The emotion is caused by your thought, not by the person or the situation itself.

Rather than blame the other person for your anger, actually feel the emotion. Notice when it manifests in your body if you can. Observe the effect of breathing into it. Watch it with a sense of care. This transforms your relationship to the anger from hate to curiosity, and thereby transforms the anger from a problem to a learning opportunity.

An easy way to remember and manage your emotions is to use the acronyn ABC:

- A: Activating event

- B: Belief

- C: Consequence

For example:

- Activating event: A colleague doesn’t turn up to a meeting.

- Belief: You believe they must always be there on time.

- Consequence: You feel annoyed.

Now go back and change your belief. Think differently, such as: ‘People aren’t always on time – that’s a fact of life. Some people are just always late. Other times, they get held up in traffic or on a slow train.’ Now you’ll notice that you’ll feel less annoyed.

So, be mindful of your beliefs whenever you feel a strong emotional reaction to someone else, and see whether changing the belief, or simply smiling at the belief, helps.

Seeing difficult people as your teachers

Relationships are built on the history between you and the other person, whoever that may be. Whenever you meet another human being, your brain automatically pulls out the memory file on the person, and you relate to him with your previous knowledge of him. This is all very well when you’re meeting an old and dearly loved friend, for example, but what about when you need to deal with someone you’ve had difficulties with in the past? Perhaps you may have had an argument or just don’t seem to connect.

Here are some ways of dealing with difficult relationships:

- Take five mindful breaths or carry out a mini meditation (check out Chapter 8) before meeting the other person. This may help prevent the feeling of anger or frustration becoming overpowering. Simple, yet awesome!

- Observe the difference between your own negative image about the person and the person himself. As best you can, let go of the image and meet the person as he is by connecting with your senses when you meet him.

- Understand the following, which Buddha is quoted as saying: ‘Remembering a wrong is like carrying a burden on the mind.’ Try to forgive whatever has happened in your relationship. See whether that helps. Buddha usually knows what he’s talking about!

- See the relationship as a game. Mindfulness is not to be taken too seriously, and nor are relationships. Often relationships become stagnant because you’re both taking things too seriously. Allow yourself to lighten up. See the funny side. Crack a joke. Or smile, at least.

- Consider what’s the worst that may happen. That question usually helps to put things back in perspective. You may be overestimating how bad the other person is, or the worst that he can realistically do to you.

- Become curious about the kind of thoughts that arise in your head when you meet the difficult person. Are the thoughts part of a familiar pattern? Can you see them as merely thoughts rather than facts? Where did you get these ideas from? This is an example of mindfulness of thoughts: becoming curious about your thinking patterns and noticing what’s happening. You’re not trying to fix or change; that happens by itself if you observe the current thought patterns clearly.

Experiment with having a very gentle smile on your face as you do the breathing space, no matter how you feel. Notice whether doing so has a positive effect on your state of mind. If it does, use this approach every time. You don’t even need to say ‘cheese’!

Experiment with having a very gentle smile on your face as you do the breathing space, no matter how you feel. Notice whether doing so has a positive effect on your state of mind. If it does, use this approach every time. You don’t even need to say ‘cheese’! If you seem to be sleeping less than usual, try not to worry about it too much. In fact, worrying about how little sleep you’re getting becomes a vicious circle. Many people sleep far less than eight hours a day, and most people have bad nights once in a while. Not being able to sleep doesn’t mean something is wrong with you, and lack of sleep isn’t the worst thing for your health. A regular mindfulness practice will probably help you in the long run.

If you seem to be sleeping less than usual, try not to worry about it too much. In fact, worrying about how little sleep you’re getting becomes a vicious circle. Many people sleep far less than eight hours a day, and most people have bad nights once in a while. Not being able to sleep doesn’t mean something is wrong with you, and lack of sleep isn’t the worst thing for your health. A regular mindfulness practice will probably help you in the long run.