Chapter 8 Drag and Drop

Remy Sharp

SO WE’VE COME to the black sheep chapter of our book: Drag and Drop. It’s not a black sheep in that cool way, like Darth Vader’s version of the Imperial Tie Fighter; no, sadly it’s the black sheep like you want to leave it alone in the field, and let it do its own thing. Some better men have even worse things to say about the spec.

So why is it here? Why is it in the HTML5 spec—and yes, drag and drop actually is part of the real HTML5 spec. Well, it’s here because Microsoft Internet Explorer added drag and drop back in 1999 in IE5—yep, that long ago. Since then, Safari had implemented IE’s API, so Ian Hickson, the HTML5 editor, reverse engineered the API, did all the hard work to understand exactly what was going on (describing the MSDN documentation as having a “vague hand-wavy description”), and documented the API.

![]() NOTE Details of Ian’s investigation can be seen here: http://ln.hixie.ch/?start=1115899732&count=1.

NOTE Details of Ian’s investigation can be seen here: http://ln.hixie.ch/?start=1115899732&count=1.

Now we’re in the position where Firefox, Safari, Chrome, and IE support this API. It’s not a good API—in fact, it’s probably the worst API—but it’s got some implementations so it’s worth understanding what it’s capable of.

Throughout this chapter, you’ll be forgiven for crying out “WTF?” as we wind our way through rabbit’s warren that is the drag and drop API. Why are we even including a chapter on this topic? It’s because there is some interesting functionality that can be achieved from the API. The API, as the name implies, allows you to drag items and drop them anywhere in the browser. But this functionality is not limited to the browser. You can drag elements from the browser to external applications—like another browser window, or Photoshop, or a text editor—and the application can prepare the dragged data so that it’s compatible with the drop target. This lends itself very well to the idea that HMTL5 is a Web Applications spec, and is giving us developers more functionality that borrows from desktop computing.

Getting into Drag

We’re going to start with the absolute minimum required to achieve the wonder that is dragging and dropping. By default, all links, text nodes (or selections of), and image elements are draggable. This means that you don’t have to do anything to tell the browser they can be dragged around the page.

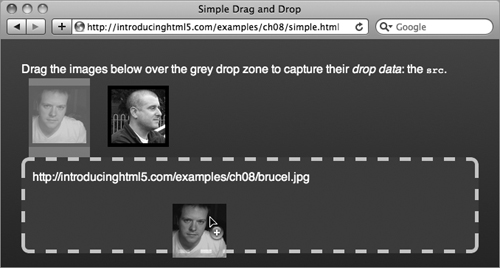

Our simple demo will have a drop zone and a couple of images that you can drag into the drop zone. And when you drop them, the image source will appear in the drop zone (see Figure 8.1).

FIGURE 8.1 All images and links are draggable by default. With a little more code, you can make them droppable too.

Since there’s nothing to be done to the draggable images, you just need to hook up the drop zone, which requires the following event handlers:

- Drag over: Tell the browser this is an element that accepts drop data.

- On drop: Once something has been dropped on the element, do something with the dropped data.

I’m explaining the absolute minimum required to achieve drag and drop, but this method is only going to work in Safari. I’ll then walk you through the tweaks required to get it to work in Firefox, Chome, and IE.

The other thing worth mentioning is that the specification up on http://dev.w3.org/html5/spec/editing.html#dnd says that there are three events you need to handle drag and drop. That isn’t the case, or certainly not when it comes to practice. You need three events to get it working in all browsers, but not in Firefox and Safari.

Let’s put all these caveats aside for a minute and crack on with our demo. The following listing is the über minimalistic source you need to see the drag and drop API in action:

I’m using the minimal HTML required just to keep things short. You can see from the previous code that I’m grabbing a reference to the div#drop element and then setting two inline event handlers: ondrop and ondragover.

When something is dropped on the drop element, it triggers the drop event and you’re able to read the event.dataTransfer object. The default data type is Text, so you can use the getData method and ask for the text data type. In the case of an image, the text will be the source of the image (typically IE gives us null for the Text data type, but you’ll fix that later). For links the href is the set data and for plain text that’s been selected and dragged, the text itself is the set data.

Here’s where it starts to get a little strange. To tell the browser that the drop element can accept items being dropped on it, you need to cancel the dragover event. Since I’m using an inline event handler (namely oneventname) I can return false. This prevents the default browser action. What is the default action? It’s unclear from the spec, but it would be fair to say the default action would be to leave the object in the control of the browser. If I were using addEventListener, I would have to use event.preventDefault().

So that you’re completely clear—because, frankly, it’s not terribly obvious—here’s a quote from the spec:

“If the drop is to be accepted, then this event (dragover) has to be canceled.”

So now that you’ve got your first drag and drop working, what about those tweaks I mentioned? Let’s fix Firefox first; this is easy. When you drop the image on the drop zone in Firefox, it actually redirects the browser off to the value of getData(‘Text’) for you if it looks like a link—that is, image sources and link hrefs. So that’s easy: In the drop event, you prevent the browser’s default action. If you’re using inline handlers, you’ll return false, or event.preventDefault(), so our drop handler now looks like this:

drop.ondrop = function (event) {

this.innerHTML += '<p>' + event.dataTransfer.getData

¬ ('Text') + '</p>';

return false;

};

Now, IE. Getting it working in IE isn’t actually as painful as it could be. This is most likely because they came up with the API in the first place. IE doesn’t listen to the dropover event, it listens for the dropenter event—and it’s this event you need to cancel for IE to play ball. So let’s add another event handler and return false, too. Since you’re doing the same thing, I’ve created a function to return false:

function cancelEvent() { return false; }

drop.ondragenter = cancelEvent;

drop.ondragover = cancelEvent;

Again, since you’re making it work in IE, IE doesn’t pass in the event object to our inline handler, so you need to change the drop event handle to grab the global event object if you didn’t receive one:

drop.ondrop = function (event) {

event = event || window.event;

this.innerHTML += '<p>' + event.dataTransfer.getData

¬ ('Text') + '</p>';

event.cancelBubble = true;

return false;

};

You also need to cancel the event from bubbling up the DOM to prevent new windows opening. Typically return false should handle this (as it does in the other browsers), but IE needs a helping hand with event.cancelBubble=true.

One final issue to fix: When you drop the image in IE or Chrome, you get “null” as the text in our drop zone. To fix this you need to set some data under the Text data type once the element starts to drag, using the dragstart event:

var imgs = document.getElementsByTagName('img'),

i = imgs.length;

while (i--) {

imgs[i].ondragstart = function (event) {

event = event || window.event;

event.dataTransfer.setData('Text', this.getAttribute

¬ ('alt'));

};

}

Now you can see that I’ve set some data whose type is “Text” based on the alt attribute on the image. Now when the image is dropped, and the Text data type is read, you’ll get the Twitter screen names instead of the image source. This drag and drop demo works in IE5 onwards, Firefox, Chrome, and Safari. More importantly, it’s the setData method that really shows off the possibilities of the drag and drop model, but equally exposes some potential issues in the specification.

Interoperability of Dragged Data

By using the setData and getData methods on the dataTransfer object, you can pass data from elements inside our application to other pages of our app, or across browser windows—as 280 Slides has prototyped, when dragging one slide from one window to another completely separate document (Figure 8.2). Finally you can also accept or send data to native desktop applications.

FIGURE 8.2 An early prototype of how drag and drop could work in 280 Slides.

Dragging Data to Other Applications

So long as you know what the accepted content types are, you can set the data type to that content type, and when you drag content from your application to that application. For example, on a Macintosh, the desktop accepts text snippets to be dragged onto it. I can construct my own content, set the content type to text/plain, and when I drag to the desktop (using Chrome or Safari), a text snippet is created with my content (Figure 8.3):

img.ondragstart = function (event) {

event = event || window.event;

// here be one long line

event.dataTransfer.setData('text/plain',

'This is the screen name for ' + this.getAttribute

¬ ('data-screen_name') +

', whose image can be found here: ' + this.src);

};

FIGURE 8.3 Dragged content from my web page creates a desktop text snippet.

One final note about setData: It only accepts strings. This means you can’t store a “complex” JavaScript object in a content type. However there’s an easy enough solution around this: JSON.stringify.

All the latest browsers ship with native JSON encoding (stringify) and decoding (parse), so you can stringify our complex object and set it against a content type. For the older browsers you can include the JSON library from http://json.org/json2.js (though host it yourself as there’s a nice little alert box you’ll need to remove that prevents hotlinking), which will plug support for JSON stringify and parse.

Problems with Setting Drag Data

Native desktop applications have had drag and drop for some time now and have had years to get the APIs right. One huge advantage that native applications have is that the setting of data doesn’t actually happen, or execute, when the user starts dragging. It happens when the user drops.

There is an important reason for this: When you drop, you only need one content type.

![]() NOTE In total, there are seven drag and drop events. You’ve seen

NOTE In total, there are seven drag and drop events. You’ve seen dragenter, dragover, drop, and dragstart. In addition there is dragend (the complement to dragstart) and dragenter and dragleave. The enter and leave events fire on the dropzone as the dragged item enters the element.

Having to construct the different content types on the dragstart event makes you perform possibly unnecessary code execution. For example, if I were to allow the user to drag a canvas element to Photoshop, I would want to encode it as a Photoshop-compatible file and store it in the correct content type. But what if I’m also supporting other formats along with Photoshop? I’d have to do all that encoding at the point in which the dragstart event fires, but the user will, at best, only drop it on a single application. What if they’re just dragging the element around to play? You’ve still run all that execution, a huge waste of processing for more complicated applications. If your application is simple, you may not see any performance issues; but if it’s a fully fledged application, you’re going to have to consider your options. Perhaps you don’t support all those formats. Perhaps you only support one compatible format. Perhaps you don’t even support drag and drop.

There are proposals to fix this (along with proposals to scrap the entire drag and drop model and start again), but for the medium term, this is a problem you’ll have to work around.

How to Drag any Element

This is where the HTML5 spec added some new content to the API. Enabling any element to be dragged is incredibly easy. Take your div and add the new attribute: draggable. For example:

<div draggable="true">This element be draggable</div>

Of course I said incredibly. Well, it works in Firefox; any element that has the draggable attribute can now be dragged around the browser. Of course, since it’s a new addition in HTML5, it doesn’t come as standard in IE, so forget about it working in IE. Perhaps it will work in IE9 or later. More incredible is getting it to work in Safari 4.

Although it’s blindingly simple to enable any element to be draggable using the draggable attribute, for reasons that are still beyond this author and many other bloggers, to get any element to drag in Safari 4 you need to give it a specific CSS style. That’s right, to enable a behaviour you need to define a presentational attribute. This has been fixed in Safari 5 so the CSS isn’t required, but for it to work in older Safari versions, you need the CSS. You must add the following CSS to target elements with the draggable attribute:

[draggable] { -webkit-user-drag: element; }

This uses the CSS attribute selector (the square brackets) to find all the elements with the property enabled, and then applies the behaviour to enable the user to drag the element.

Aside from the CSS fudge that you have to add to kick Safari 4 into life, dragging any element isn’t too hard, and it means you can now create complicated objects in the DOM that the user can move around and drop into other windows or applications.

Adding Custom Drag Icons

You can add your own custom drag icon when dragging an element. On the dragstart event, you can use the setDragImage method to associate your own image with the cursor at a specific offset to the cursor.

There’s, of course, a small caveat: It doesn’t work in IE, and in Safari, you can’t override the cursor if dragging text, images, or links. But we’re optimistic—let’s create our own custom drag icon:

var dragIcon = document.createElement('img'),

// set the drag icon to the mini twitter logo

dragIcon.src = 'http://img.tweetimag.es/i/twitter_m';

// later in the code…

element.ondragstart = function (event) {

event.dataTransfer.setDragImage(dragIcon, -10, -10);

// and do some other interesting stuff with dataTransfer

};

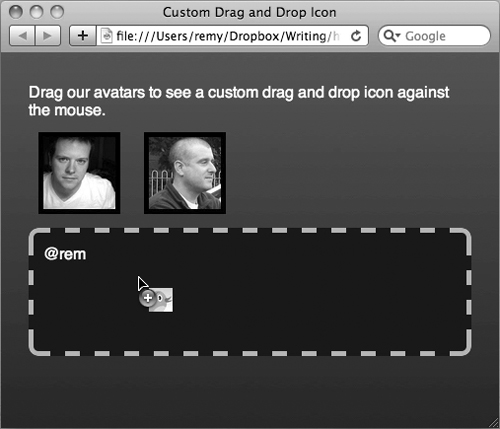

The result is a nice little bespoke drag icon that better represents the data you’re moving around (Figure 8.4).

FIGURE 8.4 We’ve created a custom Twitter cursor when dragging Twitter-related data around.

Accessibility

If you’ve made it this far undeterred by the warnings and dead bodies throughout this specification, then hopefully the application with drag and drop that you’re implementing will come under the question of accessibility. Is the drag and drop API accessible, or can I make it accessible?

Well, as you’d expect with this specification, there’s a good intention. So yes, the API has been designed with accessibility in mind. It’s not terribly clear, but latest thinking is that the user should be able to control dragging and dropping using the keyboard copy and paste model.

The process is supposed to be: Navigate to the element you want to drag, copy to the clipboard using the keyboard shortcuts, then navigate to the drop zone, and paste using the keyboard.

As you’ve probably already guessed, no browser has implemented this (yet).

However, you can prepare your drag and drop demos to include ARIA support. You will need to set ARIA attributes on dragstart to indicate that the element is being dragged. We also need to now bind to the dragend event to remove the ARIA attribute. We should also use visual cues to indicate to the user what elements can be dragged and where they can be dropped. I’m not going to cover this detail, but Gez Lemon wrote a detailed article on adding ARIA and general accessibility to nonnative drag and drop, where the practises still apply to native drag and drop: http://dev.opera.com/articles/view/accessible-drag-and-drop/

In the previous code, you’re searching for the divs that have the draggable attribute. Then you add the ARIA support starting in the dragstart event. Once the element begins to drag, you set the aria-grabbed attribute to true, so that an assistive device can feedback. You’re also now making the drop zone an element that can accept keyboard focus using tabIndex = 0 and finally you’re saying the drop effect should be ‘copy’. You could mirror the allowedEffect and dropEffect in the native drag and drop, but for now you’ll remain focused on the ARIA support.

Next, you add the new dragend event handler, and once the element is no longer being dragged, you remove the aria-grabbed attribute and reset the drop zone attributes, i.e. no tabIndex and no dropEffect. Lastly, you initialise the draggable element, by setting the tabIndex and the grab flag.

With this completed code, your users can move around your application and its drag and drop components and their screen-readers (if they support ARIA) will feed back the current state of the operation.

However—and this is a big however—since no browser has implemented the keyboard support for drag and drop, you will most likely have to consider rolling your own drag and drop using JavaScript to handle everything (instead of relying on the native drag and drop functionality)—a rather sad ending to what is a particularly common operation on the web.

Summary

The drag and drop API isn’t in a great state and can be difficult to implement across all the browsers your application may support. In fact you may find you have to fall back to a JavaScript-based solution to drag and drop where the support is lacking.

However, native drag and drop, combined with newer APIs like the File API (out of scope of this book, but it allows the browser to read files without the server side) allows users to drag files straight into the browser. These kinds of features are appearing as beta features in applications such as Gmail, allowing users with browsers that support the bleeding edge drag and drop API, if there is such a thing, to experience the very latest technology.

You’ll need to carefully weigh up whether native drag and drop is the right choice for your application.