Chapter Six

Independent Public-Services Providers

A New Potential Collaborator

Independent public-services providers (IPSPs) present the newest option for collaboration to public managers. These new entities at first appearance may look similar to networks or partnerships. Yet IPSPs have an approach to governance that makes them distinctive and offers a unique collaborative opportunity to public managers. All the other cross-sector collaborations (CSC) involve activities and relationships that advance the specific goals of a government program or policy. Collaborating with IPSPs is unique because the public service being provided is determined by the IPSP, not government.

Among all of the CSC considered here, IPSPs have two extreme conditions of collaboration for public managers. IPSPs can offer the most innovative approaches to delivering public services, since they are able to pursue their own priorities independent of the numerous constraints that govern public administration. They also thrive on designing and implementing public services that are more effective than conventional approaches employed by other collaborations that governments may engage. IPSPs, however, also operate outside government’s sphere of control. Their independence can make them odd collaborators for public managers, who are used to setting agendas, directions, and deliverables in their collaborations.

Public managers need to learn how to engage IPSPs in a different manner from the conventional hierarchical, top-down approach used with employees and contractors. IPSPs hold a special status as collaborators with governments. They are pioneering entities that are part of the emerging idea of new governance, a concept that is increasingly complementing the traditional concept of government. Governance includes not only governments but also other organizations that are providing public goods and services (Peters and Pierre 1998).

As potential collaborators, IPSPs have an obvious appeal for government. When IPSPs are providing services that are consistent with public policy goals and objectives, public managers may choose to support these operations through collaboration. It is an opportunity to meet a public agency’s obligations at minimal cost. The lack of direct control over what public services are provided by IPSPs and how they provide them, however, raise serious worries about accountability and how to report on these collaborations to publicly elected officials.

DEFINING PUBLIC ENTERPRISE ORGANIZATIONS

In chapter 1 we defined IPSPs as self-directed entities composed of businesses, nonprofit organizations (often referred to as nongovernmental organizations), and governmental units that collaborate in the production or delivery of public goods or services.

IPSPs have unique characteristics that make them different from collaborations with the PPPs, partnerships, and networks discussed thus far. The defining characteristics of a IPSP are displayed in figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Independent Public-Services Providers Profile

Although the individual characteristics of an IPSP by themselves are not unique, the combination of all three makes IPSPs distinctive collaborative partners and unique actors on the governance landscape:

- The multisector circle also represents organizations that do not provide public services and are not self-directed, such as alliances between nonprofits and business.

- The public services circle includes organizations such as national, state, and local governments and various quasi-governmental organizations that are within the traditional government hierarchy and provide services to the public but are not multisector.

- The self-directed circle includes both for-profit and nonprofit organizations that provide goods and services and exist in only one sector. One example is a company that has the freedom to make its own decisions (it is self-directed), sells goods and services for profit, and works solely in the private sector.

IPSPs operate within the shaded part of the circles at the very center of the diagram where these three characteristics are unified. That is, IPSPs have all three characteristics:

- IPSPs are largely self-directed. They do not operate within a traditional government hierarchy and often act independently of government. As a result, they have the freedom to think about issues and deliver public goods and services in a manner that may not necessarily conform to convention or only to those perspectives endorsed by government agencies. They also operate outside the constraints inherent in a federal system with its checks and balances. Because there is no direct oversight by public officials, they are able to act with greater efficiency, creativity, and purposefulness. Thus, IPSPs can offer new, innovative approaches that are more responsive to the public and can address challenging public policy problems more effectively.

- IPSPs comprise multiple stakeholders. They have diverse views and accommodate different perspectives and interests. In this way, IPSPs can claim a measure of legitimacy (when they properly represent the interests of appropriate stakeholders). Having multiple participants allows collaborations that combine the skills and experiences necessary to meet their goals and adapt to local circumstances in innovative ways.

- IPSPs provide public goods and services. They serve in the place of governments and interact directly with the public. They often provide services that citizens might otherwise expect governments to provide, but they may provide a better option or the only option. Too often governments do not have sufficient funding to provide all the services that communities need.

In contrast to contractors, partnerships, and networks, IPSPs act with a greater discretion and autonomy in determining the types and methods of services they provide, a characteristic that places them outside the governmental framework, even when government may be involved. IPSPs are sometimes formed ad hoc; at other times, they are more permanent, structured through formal organizational structures or through contracts, memorandums of understanding (MOUs), or informal agreements; and often they are created without any government involvement at all. They provide enormous opportunities to supplement traditional governmental agencies to meet today’s critical problems.

THE GROWTH OF QUASI-GOVERNMENTAL AND HYBRID ORGANIZATIONS

The idea of operating outside the usual administrative boundaries of government as a strategy to improve the performance of some functions thought important by government is not new. Throughout US history, the federal government, and more recently state governments, has created entities that operate outside government’s conventional administrative structures to carry out specific public functions. These entities represent a diverse set of arrangements and responsibilities; however, they share the characteristic of conducting activities on behalf of the government but not being under the direct authority of a government agency. Examples at the national level include:

- Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac)

- National Railroad Passenger Corporation (AMTRAK)

- National Dairy Promotion and Research Board

- The National Park Foundation

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board

These entities and scores more represent what have come to be known as quasi-governmental entities. They are called quasi-governmental because they were created by the government and have ties to the executive branch but do not act as agencies as defined by the US Code. They carry out their mission, judged to be for a public purpose, but most often they do not have to operate under government procurement or personnel requirements. Although there is no clear-cut definition of quasi-governmental and they undertake a diverse range of functions, these entities conduct important government operations. An analysis by the Congressional Research Service identifies seven types of such organizations at the federal level. A summary review of some of the types of organizations demonstrates their variety (Kosar 2011):

- Quasi-official agencies, such as the Legal Services Corporation, the Smithsonian Institution, and the US Institute of Peace, are not executive agencies, but are required to publish certain information about their programs and receive direct funding from the federal budget.

- Government-sponsored enterprises, such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Bank System, are corporate entities established by federal law; they are privately owned and operate under a board of directors composed primarily of private owners.

- Federally funded research and development corporations, such as the National Laboratories at Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, are designed to address a federal need for research focused on specific topics through the application of private scientific and engineering skills. They are exempt from federal civil service rules and are operated under long-term (often sole-source) contracts initiated by government agencies, such as the Department of Energy.

- Agency-related nonprofit organizations have a legal relationship with a department or agency of the federal government in one of three ways: (1) adjunct organizations under the control of a department or agency (such as the Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Commodity Promotion Boards); (2) independent organizations created by federal statute that are dependent on or serve a federal department or agency (such as the nonprofit Veterans Administration medical centers of research and education); and (3) nonprofit organizations (created under federal law or state statutes) that are voluntarily affiliated with departments or agencies, such as nonprofit state park organizations.

- The other three quasi-governmental types that Kosar identified are federal venture capital funds; congressionally chartered nonprofit organizations, such as the Red Cross and the National Academy of Public Administration; and other entities that do not fit neatly into any category.

State governments also have created a number of quasi-governmental units. These include such organizations as airport authorities, building and housing authorities, and lottery commissions. Governments imbue these quasi-governmental organizations with a mission that contains a public purpose without hindering their operations with the typical governmental hierarchy and red tape.

Distinguishing IPSPs from Quasi-Governmental Entities

Despite their special status and their exemption from government procurement and human resources policies, quasi-governmental should not be confused with IPSPs. Quasi-governmental entities are created by an act of Congress or state legislatures; the very fact that they exist is a decision by government with a specific public purpose in mind. Their authority to act is vested in such legislation. IPSPs are not created by government (although there may be general authorizing legislation for them to exist and conduct their operations); they are arrangements that are formed voluntarily. IPSPs may, and sometimes do, collaborate with government through contracts or agreements, but not because the government created them. IPSPs “invent themselves” and can convene, change membership, or disband as the members decide.

In addition, the authority conveyed to quasi-governmental entities is specified, allowing a certain legal authority to act and limiting other kinds of actions. For example, regional airport authorities (sometimes multistate entities) have the authority to sell bonds without government approval, but the use of the funds from those bonds is restricted. The US secretary of energy cannot direct the specific research agenda or projects the National Renewable Energy Laboratory undertakes, but the laboratory is restricted to the general topics to which its research is directed.

In contrast, IPSPs choose their mission, and that mission is negotiated among its members. Of course, some IPSPs carry out missions that are consistent with government policy, but the choice to promote such policies comes from their own impetus. Therefore, IPSPs also are not subject to government oversight to the same extent as quasi-governmental organizations. In short, because IPSPs are not created by the power of the government, that same government has limited influence over them without engaging in an effective collaboration.

Distinguishing IPSPs from Other CSCs

Having defined IPSPs, it is easy to see how they could look similar to other CSCs. For example, nearly all IPSPs are formed as nonprofits. In addition, many organize as a network or join in partnership with other organizations. So what separates IPSPs from the partnerships and networks discussed earlier? IPSPs may look similar to these other organizations, but they act differently in important ways.

While IPSPs may share characteristics with other CSCs such as partnerships and networks, it is the combination of the three specific characteristics that makes them singular as a potential collaborator. First, IPSPs form with the intent to collaborate with stakeholders. The reason they form in the first place is to provide a different approach to delivering public services grounded in multisector collaboration. Some nonprofits also collaborate, but that is incidental to their mission and identity. That is, a nonprofit would still be a nonprofit whether it collaborated with others or not, but for an IPSP, collaboration is an important aspect of its core mission. Any nonprofit that embraces multisector collaboration as its primary approach to delivering public services might be considered an IPSP.

Second, IPSPs are self-directed and operate separately from government direction. In this way, they are distinguished from the networks discussed in chapter 5. Networks enhance and expand the resources and capabilities available to governments and are linked to a government organization. IPSPs create their own missions and determine their own operations for the very reason that they want to improve on the current practice. Since IPSPs act in collaboration with other organizations (including governments), their efforts may incorporate some government programs into a more integrated and comprehensive approach. In addition, IPSPs are not precluded from accepting grants from governments, but they do not let government funding or government policies guide their activities. It is the reason the IPSP was created in the first place: to be a self-directed operation that offers a new vision, a new approach to governance, and a new way to collaborate,

Third, IPSPs provide public services. Of course, all the other collaborations we discuss in the book provide public services as well. However, in the other CSCs, the services provided are those defined by government policy. Most public services have requirements for eligibility and other conditions that have to be met by those receiving the services. Government agencies have budgets and must put limits on the scope and scale of what they can do. The public services provided by IPSPs are the type they want to provide (within the law), and in this way IPSPs may offer public services that are distinctive or may be newly accessible to communities. While a great deal has been written on the role of the nonprofit (third) sector to address social problems outside government direction, we also bring to light private sector initiatives (often with a nonprofit) rooted in social entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility that provide goods and services for the public.

IPSPs are distinguished not by being a nonprofit—although they usually are—or organizing their operations as a network—although they often do—but by also existing outside the purview of government direction, and often government funding, and yet still providing what would be considered public services. They are emerging as a new potential collaborator for the provision of public services, but at the same time they stretch the limits of government’s ability to control or even manage the delivery of those public services. Therefore, they are the most challenging of collaborations for public managers.

IPSPs AND THE CHALLENGING GOVERNANCE ENVIRONMENT

Global climate change and related environmental challenges, our deteriorating national infrastructure, and perpetual health care crises are just three of many societal challenges that will require new thinking and innovative solutions by public managers. How do some IPSPs address these challenges?

Protecting the Environment: Climate Change and Sustainability

Climate change continues to be a hotly contested issue, with potentially disastrous long-term consequences for the planet and with no comprehensive solution in sight. Despite the Obama administration’s recent Climate Action Plan (White House 2013) to reduce US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the level of significant GHG reductions needed is so large, the sources of those emissions so diverse, and the cost of remediation so extensive that the scope of any solution that effectively addresses climate change will necessarily transcend sectors and political boundaries—domestic and international. Regulating air quality has been a priority of the federal government—in partnership with state governments—since the Clean Air Act of 1970. Yet even the authority of the federal government to regulate GHGs remains a political controversy. International agreements and protocols attempting to curb GHGs have resulted in over two decades of frustration, from Rio, Kyoto, and Copenhagen to Dubai, with governments unable to secure binding agreements on GHG reduction requirements and standards.

The diverse and serious effects of global warming stretch across sectors, regions, income classes, and states. The inability of governments to respond to concerns over climate change and sustainability has sparked action by private firms and nonprofits to begin to take action. Activities undertaken by concerned citizens, nonprofits, businesses, and community groups currently have surpassed the public sector efforts to reduce carbon footprints and develop alternative sustainability policies.

The Rainforest Alliance

The Rainforest Alliance was established in 1987 in an attempt to conserve biodiversity and promote sustainability by changing land use practices, business practices, and consumer behavior. The alliance uses the power of markets to arrest the major drivers of deforestation and environmental destruction: timber extraction, agricultural expansion, cattle ranching, and tourism. It builds coalitions with businesses, nonprofits, governmental entities, and individuals to support and develop guidelines for climate-friendly farming, and it links businesses that identify their goods and services as Rainforest Alliance Certified and Rainforest Alliance Verified to conscientious consumers who buy their certified products.

The Rainforest Alliance has worked with a coalition of more than two hundred organizations to promote sustainable tourism globally; it formed the Global Sustainable Tourism Council, which established minimum standards that any tourism business should aspire to reach in order to protect and sustain the world’s natural and cultural resources, while ensuring that tourism meets its potential as a tool for poverty alleviation (Rainforest Alliance 2012). While the Rainforest Alliance works with governments and governmental organizations, its members are largely nongovernmental and are responsible for driving the agenda of the organization; thus their industry standards are not governmental. Their nongovernmental certification is sought after by private companies.

Joint Venture–Silicon Valley

Joint Venture–Silicon Valley (Joint Venture–SV) was born as an experiment to coalesce a multisector, collaborative group from the public and private sectors to create a neutral forum for leaders to discuss issues affecting the region. The group engages leaders in business, government, academia, labor, and the nonprofit sector to bring together the best strategies and reach a consensus on solutions. As Russell Hancock, president and CEO, put it, “We all work together, but we set our priorities.” Part of the inspiration for its formation is preserving the image of the Silicon Valley region as a leader in innovation and entrepreneurship.

Joint Venture–SV collaborates to address issues of economic development, infrastructure, transportation, communications, education, health care, disaster planning, and climate change. Its new SEEDZ (Smart Energy Enterprise Development Zone) program attempts to create “the smart energy network of the future.” The goal is, by 2020, to create the country’s highest-performance two-way power network, supporting and rewarding active energy management and clean distributed generation on a sustainable economic scale. Reduced demand for energy corresponds to lower GHG emissions (Joint Venture–Silicon Valley 2013). To realize these ambitious energy efficiency dreams, Joint Venture uses its network of influential board directors representing business, nonprofits, and government. The group’s collaborative culture facilitates its efforts to unify diverse stakeholders and provide faster, cheaper, and more efficient energy sources while simultaneously discovering new areas of profitability for its member firms.

The Oregon Environmental Council

The Oregon Environmental Council (OEC) reflects the mission of many IPSPs dedicated to promoting sustainability and addressing climate change. OEC was formed in 1968 by a group of citizens with the broad goal to protect Oregon’s environment. Today as a nonprofit, membership-based organization, the OEC focuses on solving global warming, protecting citizens from exposure to toxic substances, cleaning up rivers, building sustainable economies, ensuring healthy food and local farms, and passing strong environmental policies. Its partners include individuals from or programs within Oregon State University, Zipcar–Portland, MKG Financial Group, Renaissance Foundation, Oregon Wine Board, and American Lung Association of Oregon.

OEC relies on a diverse membership and its engagement with other organizations to create a unique entity dedicated to improving the environment in Oregon (Oregon Environmental Council 2011). One of its main goals is protecting Oregonians from pollution, such as the level of exposure people face from toxic chemicals found in the environment. An example is the Green Chemistry initiative, which focuses on reducing the hazards of toxic chemicals and transitioning to less toxic renewable feedstock. The initiative began with the Oregon Green Chemistry Advisory Group in 2009, which brought together leaders of academia, industry, and agencies to identify and examine green chemistry options and opportunities. Following up on the findings, the OEC works directly with individual groups to share the research findings and help them develop greener and healthier practices for using chemicals.

Each of these IPSPs has formed a coalition to address climate change and sustainability in different ways. The Rainforest Alliance sets standards for forest conservation and has mechanisms for industry adoption. Silicon Valley–Joint Venture uses a business case approach to persuade its members to adopt sustainability practices that reduce their GHG footprint. The Oregon Environmental Council advances a shared stewardship vision of the environment in its state and promotes sustainability practices, including reduction of GHGs. Of course, the efforts of these IPSPs will not solve climate change problems, nor will the efforts of the scores of other IPSPs solve all environmental issues. Nevertheless, these three examples illustrate the types of actions IPSPs can undertake when addressing the problem of climate change, and they offer public managers many options to address climate change outside the parameters of current government policy.

Transportation Infrastructure: Reducing Travel Congestion and Improving Safety

The transportation sector in the United States is severely hampered by the fiscal challenges facing federal, state, and local governments. Government and transportation association reports have raised an alarm over the inability of government authorities at federal, state, and local levels to address the existing demands on our nation’s transportation system. US roadways alone need a dramatic rise in investment over the next decades to address repairs and expansion needs (US General Accountability Office 2008). The failure on the part of governments to build and maintain an adequate transportation infrastructure has led to congestion in major urban areas and transit choke points for commerce across the nation. Despite the warnings, federal government spending on highways has remained largely steady during the past ten years and is projected to remain at that level for the decade ahead (Congressional Budget Office 2011).

With so much pressure on government to do more with less to address infrastructure capacity issues and with the related issues of safety and terrorism prevention, there is enormous potential for organizations from outside government to contribute to transportation financing, provision, safety, and maintenance. The private sector relies on transportation systems to move their goods; this need has sparked efforts to improve transportation infrastructure and ease congestion problems through the efforts of IPSPs.

Channel Industries Mutual Aid and the Houston Ship Channel

The Houston Ship Channel is recognized as one of the most important routes of commerce for Texas. Infrastructure operators surrounding the channel and businesses dependent on this route for trade have long worked together to mitigate the risk of natural disasters and, more recently, terrorist attacks on the facility. In 1960, Channel Industries Mutual Aid (CIMA) was formed as a nonprofit and has worked collaboratively to join together firefighting, rescue, and first-aid manpower and equipment among Houston Ship Channel industries and municipalities for mutual assistance in case of emergency situations—either natural or man-made.

CIMA’s current membership consists of approximately one hundred members from industry, municipalities, and government agencies covering Harris, Chambers, and Brazoria counties of Texas. It has numerous programs as part of its capacity to provide an organized response in times of disaster: a centralized dispatch system, a prearranged alarm list database for its members, a multicasualty incident plan, roadblock committees, and technical advice groups. CIMA maintains its preparedness for response by managing a well-detailed action plan, training, and formal reviews after each incident.

Although CIMA was established for the Houston Ship Channel area, it maintains agreements with several other mutual aid organizations along the Texas/Louisiana coast to provide assistance or receive it during major events. CIMA is recognized as one of the largest mutual aid organizations in the world and has shared its experience and procedures with other mutual aid organizations and countries, including the International Red Cross, Germany, Switzerland, and Australia (Channel Industries Mutual Aid 2014). What makes CIMA an interesting illustration of an IPSP is how the network developed out of the interests of the industry groups that depend on security at the Houston Ship Channel. They recognized the need for collective action to address security issues, and they have gradually incorporated more participation and contributions from the public sector. Public managers took advantage of the privately initiated organization to supplement government capabilities.

The First Response Team of America

The First Response Team of America (FRTA) was founded as a nonprofit organization that works to supply emergency aid to disaster-stricken areas. Since its founding in May 2007, FRTA has helped US communities with postdisaster relief from tornados, primarily in northern Georgia and Alabama. It also provides hospitals, nursing homes, shelters, and command posts with electricity from Caterpillar equipment in disaster zones. The IPSP has assisted in reducing the time of emergency responses in forty disaster sites in the United States, providing emergency aid to thousands of disaster victims (Business Civic Leadership Center 2012).

One of FRTA’s vital collaborators is the Caterpillar Corporation. Together they developed an innovative approach for clearing roadways after a major natural disaster in the United States to reduce the time for first responders and law enforcement officials to enter affected areas and gain access to victims. Working with the Caterpillar Corporation and other heavy equipment manufacturers, FRTA has been able to accrue a sophisticated collection of rescue gear and roadway clearance vehicles available for a response to disasters (Caterpillar 2012).

The interest of industry, nonprofits, and local communities in having open roadways and waterways after a disaster has prompted IPSPs to step in and act in the face of inadequate investment by the government in infrastructure. CIMA members coordinate industry-led efforts to secure access to waterways in Houston after a disaster. Similarly, FRTA anticipates the impact of natural disasters on roadway access and clears roadways so first responders can get to victims quickly. Both examples illustrate the value of investing in contingency plans and readiness, an approach many governments do not take. The combination of private and nonprofit interests around this issue created a unique opportunity for IPSPs in disaster response. IPSPs are providing a public service that is an assumed responsibility of local governments. This has implications for many other operations essential after a disaster.

Health Care Crises: Improving Access and Reducing Costs

As the debate in the 2012 presidential election over Medicare, Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act (popularly known as Obamacare), and health care costs illustrated, health care policy in the United States is at a critical juncture. While health care is state of the art in the United States, many residents lack essential health care coverage, and health care cost increases regularly exceed standard measures of inflation, placing this cost on an unsustainable path. In many other nations, especially in the less-developed world, health care is not available to a substantial portion of their population, and control of basic diseases, HIV, typhoid, and others is a primary health care need.

Public health is generally a responsibility of government, although the degree of government involvement in health care design and delivery is often controversial. Governments have used both the private and nonprofit sectors to deliver essential aspects of health care. That approach is predominant in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in other countries. Therefore, at least in the United States, it would seem logical for all sectors to be involved in developing and implementing solutions. Both private and nonprofit health care providers have an incentive to hold down costs: to be more competitive or serve larger markets or populations not yet served. Since health expenditures represent more than one-fifth of the US economy, the private sector has a strong profit motive to increase efficiency. Governments in developing nations may simply lack the resources to address some of their most critical health problems. Thus, it seems logical for the private and nonprofit sectors to develop alliances with and without government to address these issues.

Accountable Care Organizations

In the United States, one of the most promising initiatives to improve care and contain costs is the development of accountable care organizations (ACO). The term ACO was coined by Dr. Elliott Fisher and others in 2006 to describe the development of partnerships between hospitals and physicians (both private and nonprofits) to coordinate and deliver efficient care (Fisher 2006). The ACO concept seeks to remove existing barriers to improving health care, including shifting from a payment system that rewards the volume and intensity of provided services to one that focuses on quality and cost performance (Fisher 2009). Two illustrations of ACOs are Pathways to Health and Community Care of North Carolina.

In 2006, Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) developed the concept of integrated health partners that was later restructured into Pathways to Health, a framework that includes several local health care stakeholders such as insurers, consumers, and employers interested in reducing hospitalization and improving chronic care delivery in their area. Pathways to Health features key ACO concepts such as a patient-centered medical home (for primary care and case management), value-based purchasing, and community buy-in. The collaboration is currently developing a new payment structure and improving its patient data collection efforts. BCBSM reported that hospitalizations for conditions that can be prevented through better ambulatory care dropped 40 percent over the first three years of the program (Simmons 2010). While governments gain from the reduced program operating costs (especially Medicare and Medicaid savings), the cost reductions are being driven by IPSPs that are entirely nongovernmental.

Since 1998, the State of North Carolina has operated Community Care of North Carolina, a statewide medical program supported by the state’s Medicaid program. Community Care evolved from an effort in 1983 by a local foundation to test approaches for improving primary care physician participation in Medicaid. The North Carolina Foundation for Advanced Health Programs, in partnership with state and county organizations, submitted a proposal to a private foundation to pilot North Carolina’s first effort at developing medical homes for Medicaid recipients. This program has gradually expanded statewide and now consists of a community health network organized collaboratively by hospitals, physicians, health departments, and social service organizations to manage care. Each enrollee is assigned to a specific primary care provider, and network case managers partner with physicians and hospitals to identify and manage care for high-cost patients. In 2006, the program saved the state between $150 million and $170 million (Kaiser Commission 2009). Although government has been involved in Community Care, the driving force came from nonprofits and a private foundation. In this case, the IPSP began without direct governmental assistance, but is now integrated into the way government provides assistance to its low-income population, so it is beginning to look more like a governmental network. This example shows how IPSPs might morph into something with more direct governmental ties.

The success of the ACO model in fostering clinical excellence and continual improvement while effectively managing costs hinges on its ability to incentivize hospitals, physicians, post–acute care facilities, and other involved providers to form linkages that facilitate the coordination of care delivery and the collection and analysis of data on costs and outcomes (Nelson 2009). The ACO collaboratives must have organizational capacity to establish an administrative body to manage patient care, ensure high-quality care (including measuring outcomes), receive and distribute payments, and manage financial risk (American Hospital Association 2010).

The ACO model was initiated in the private and nonprofit sectors, and its potential led the Obama administration to include the concept in its national health care reform legislation as one of several demonstration programs to be administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The ACOs participating in that program would assume accountability for improving the quality and cost of care for a defined patient population of Medicare beneficiaries. As proposed, ACOs would receive part of any savings generated from care coordination as long as benchmarks for the quality of care are also maintained. Initial analysis of ACO’s pioneer and pilot projects has indicated savings of $380 million (US Health and Human Services 2014). ACOs are now being created nationwide and have a potential to expand beyond the Medicare and Medicaid populations.

Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases

The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases (GNNTD) was launched in 2006 at President Bill Clinton’s Global Initiative Annual Meeting. The Global Network’s job is to work with global partners to help deliver vital medical solutions to communities with the greatest needs. The Sabin Vaccine Institute Board of Trustees oversees its activities. Its board of trustees is composed of international leaders in business, civil service, academia, and philanthropy. Partners include academic institutions, foundations, and a variety of nonprofit organizations dedicated to addressing neglected tropical diseases. GNNTD seeks to achieve solutions through a three-pronged approach:

- Advocacy and policy change

- Resource mobilization

- Global coordination

Pharmaceutical companies are donating medicines to fight neglected diseases such as schistosomiasis; it costs approximately fifty cents to treat and protect one person for up to a year, but those funds are not available in developing nations. The GNNTD illustrates the importance of private and nonprofit actors in addressing global health issues. Governments can assist in facilitating treatment and funding, but the initiation and direction are outside the governmental bureaucracy, allowing flexibility in approach and funding (GNNTD 2013).

The GNNTD is a classic example of an IPSP: it was formed by a coalition of private and nonprofit actors. Although it collaborates closely with the World Health Organization and seeks and receives some support from governments, its policies and programs are driven by its nongovernmental board of trustees.

IPSPs and Their Approach

The examples demonstrate the diverse set of activities in which IPSPs have become involved. Earlier in the chapter, we presented a diagram that represented the unique characteristics of IPSPs. We have placed the IPSPs we have discussed in that same diagram (see figure 6.2). The differences among IPSPs reflect their own unique approach to governance. The display of where different IPSPs fit in the diagram illustrates the variations public managers will find among different IPSPs.

Figure 6.2 IPSPs and Their Approach

Of course, not all IPSPs are exactly the same. They vary in the extent to which they reflect the three principal traits of IPSPs. Some have only a few partners but still represent multiple sectors. Some are more closely aligned with governments, although they remain self-directed. For example, the Oregon Environmental Council is self-directed and multisectored, but it might be considered limited in its direct provision of public services. Such differences are important for public managers to recognize and understand in order to make the most effective collaborations.

The placement of the IPSPs described in figure 6.2 demonstrates the variations in the characteristics and approaches IPSPs take, for example:

- The Oregon Environmental Council has members representing all three sectors, and it is strongly self-directed, but its direct public services are limited, providing information about what to do more than doing it themselves.

- First Response Team of America provides public services in the way of road clearing and acts independent of government policies, but its members are a relatively small coalition of community groups and industry partners.

- The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases has a diverse set of members across national and international sectors and provides an obvious public service in the distribution of medicines. Its policies are consistent with government policies of the United States and international health organizations, although its approach to implementation is innovative and adaptive.

All IPSPs have their own unique profile and vary in the scope and intensity of the three defining characteristics. As we have noted, they are dynamic and evolve as organizations over time. Our presentation of IPSPs in figure 6.2 reflects a period of time, but it would not be surprising to see that IPSPs would migrate to different points in the diagram as they evolve.

THE PUBLIC MANAGER AND IPSPs

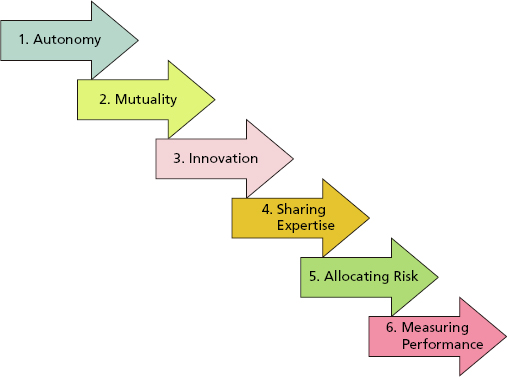

While public managers typically have limited influence over the creation and operation of IPSPs, they should have an understanding of what makes for a successful relationship with IPSPs. Figure 6.3 provides the elements that are most important for a successful IPSP collaboration.

Figure 6.3 Elements of IPSP Engagement

Autonomy

IPSPs gain their flexibility from their autonomy from government. This does not mean they should not work with government; the whole premise of an IPSP is its freedom to engage a wide range of actors, both outside the government sphere of authority and potentially including government. From the public manager’s perspective, the autonomy of the IPSP is valuable because it enables the organization to address areas that government may be constrained to address. The self-directing nature of IPSPs implies that government will have limited means to control or manage the operations of IPSPs. The more independent the nature of IPSPs, the greater the imperative for government managers to adopt a leadership style of accommodation and cooperation with nonprofit and private sector members of an IPSP.

Although public managers may be used to managing external relationships from a position of making the final decisions due to government funding and legal authority, it is not in the public interest for the pubic manager to attempt to co-opt an IPSP. A public manager may want to influence the IPSP to address particular public concerns or modify a program to avoid conflicts with existing public policy. The public manager should ask two questions: (1) Are the goals and objectives of the IPSP in line with current public policy? (2) Are they addressing a need not currently being addressed by government? If the answer to either question is yes, the public manager’s role may simply be a facilitator or cheerleader for the actions of the IPSP. If the answer to both questions is no, or is ambiguous, the public manager will need to examine what sources of power or leverage the government has over the IPSP that may mold the IPSP more in the direction of government policy.

The Rainforest Alliance’s globally autonomous nature allows it the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances and develop new approaches and solutions that fit best at the time. The ability to try an approach and then discard it for an alternative one, when participants believe change is needed, is not what characterizes most government agencies. Innovative problem solving and adaptation make the Rainforest Alliance a useful partner for public managers.

Mutuality

Just as in networks, all parties in an IPSP must have something to gain from participation in the collaboration. Collaboration takes more time and effort than acting unilaterally. Members might participate for various reasons, but they will not stay engaged very long unless they believe they will benefit from their efforts. The benefits gained may be monetary, such as increased opportunities for financial support or increased sales, but the advantages participants believe they gain from participation in an IPSP can be diverse and not always obvious. The key is achieving a level of mutuality whereby the parties to the collaboration are able to maintain their respective identities and missions while contributing to the collaboration.

Public managers must discern the potential gain for their own involvement with an IPSP. The IPSP may be performing a governmental function that saves the government from providing such services to a particular community. If so, the public manager might examine whether it is possible to provide some governmental funding, for example, through grants or contracts, that would provide additional resources to the IPSP. The Obama administration’s support of accountable care organizations, which clearly address a major theme of health care reform, is one illustration of ways government can support the actions of IPSPs.

As an example of the importance of mutuality in an IPSP, Joint Venture–SV’s broad and diverse leadership provides the backbone to support its energy-efficiency goals. Without this unified approach to collaborating and directing their approach, the complexity in implementing their sustainability initiatives makes achieving their goals unreachable.

Innovation

An IPSP’s strength is its ability to innovate. It can provide creative solutions that might otherwise never emerge from government agencies. Of course, not all ideas and innovations will work, but IPSPs, more than government, are able to take on the risk of failure and embrace innovative, systemic thinking and creative problem solving.

Successes by IPSPs can lead to new or revamped government programs to address public problems and issues. Public managers can benefit by learning what works and does not as IPSPs look for unique solutions—something that governments do not do so well. Public managers should encourage IPSP innovation through pilot project grants and other mechanisms. From an intergovernmental perspective, state governments often are referred to as “laboratories of democracy.” IPSPs might be considered “laboratories of innovation.” The North Carolina Community Care program is a good illustration of a laboratory of innovation that led the state government to incorporate the program’s approach into how it delivers health care services to a particular population in the state.

Sharing Expertise and Resources

Transparency and openness are important aspects of successful IPSP operations. Hiding information, often a problem in principal-agent relations, is counterproductive in IPSPs, where the whole objective of the organization is to combine the capabilities of the various participants. Since the success of the IPSP will be measured in terms of shared goals and outcomes, there is little reason for its members to withhold their ideas or intentions that might be necessary for success. IPSPs that are successful in convincing partners to share information save everyone time and energy, which otherwise is too often spent and wasted on protracted negotiations and circular discussions.

From the public manager’s perspective, government may have expertise and resources that would be useful to an IPSP and provide some leverage for public managers to influence the approach used by an IPSP to address particular problems. For example, government provides a certain legitimacy, so that government support might be useful for an IPSP to gain acceptance by particular constituencies. Government does have regulatory control over many areas, including health care, environmental protection, and workplace safety. The ability of public managers to help IPSPs navigate the regulatory bureaucracy or provide waivers to IPSPs may be an important power—one not to be used over the IPSP but to assist the IPSP in fulfilling its goals and objectives in line with the public interest. The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases shows how combining resources and dispersing them in a well-informed manner can provide significant relief to disease-stricken regions around the world.

Allocating Risk

Just as in partnerships and networks, all members of an IPSP need to assume the risks they are best able to deal with. Thus, production costs might best be borne by a private sector member of an IPSP, whereas delivery systems might be better controlled by a local nonprofit that has contacts and experience dealing with a specific clientele.

From a public manager’s perspective, government has little risk with IPSPs other than a risk of the IPSP actually making a problem worse. However, there may be some risks that would make sense for government to assume in support of IPSP activities. Government might be the insurer of last resort for certain types of liability, or it may use its legislative power to restrict the ability of individuals to take legal action if they feel they have been wronged by an IPSP. The only reason government might want to assume that role is if it felt that an IPSP was performing an important public function and believed the IPSP would be greatly hindered in its operations by potential liability. Clearing Roadways in Disaster Recovery provides an example in which significant monetary and implementation risks were divided and reallocated by combining the goals of publicly oriented nonprofits and financially interested firms to efficiently rehabilitate transportation to disaster areas.

Measuring Performance

As with any other well-run organization, IPSPs should have a mechanism to measure the performance of their operations. Measurements may include output measures (such as number of children receiving medication), outcome measures (such as overall health in a community), and organizational measures (such as cost of delivery per person served). Timely benchmarks and measurements are important aspects of effective organizational performance.

The public manager will want to weigh the performance measurements of an IPSP against public policy objectives. It may be that the manager is in a better position to collect the data necessary to assess whether an IPSP is meeting the public interest in its activities. Government might be the only party that can collect certain data because of privacy issues, and the ability of government to provide measurements may assist IPSPs in meeting their objectives while providing the public manager with assurances that the IPSP is operating in the public interest.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES FOR PUBLIC MANAGERS WORKING WITH IPSPs

Working with IPSPs can give public managers an opportunity to address policy issues and program implementation in a fresh way. They also can present challenges to public managers and may raise questions about whether they are the optimal form of collaboration.

Advantages for Public Managers

IPSPs offer public managers numerous advantages over other forms of collaborations because of the diversity of participants, their operations outside the basic realms of government, and their commitment to meaningful collaborations.

- Additional resources. IPSPs typically receive funding support from foundations, private donations, and fees for their operations. Public managers most often are constrained by their budgets. By learning how to collaborate with IPSPs, public managers can expand the resource base available to solve the problems their agency is charged with addressing.

- Political sensitivities. Trying new approaches to the delivery of public services can prove to be politically sensitive. Public officials and constituencies may object to changes in programs that have been routine, even if the intent is to bring about improvements, and especially if it involves untested approaches with uncertain results. IPSPs can serve as laboratories of innovation and advance new ideas without public managers facing the risks of being criticized.

- Long-term view. When IPSP collaborations are approaching issues of a long-term-view nature, such as adequate funding for maintenance of infrastructure or capital equipment replacement, public managers can use that perspective to consider issues beyond the typical government time frame of a one- or two-year budget cycle.

- Social entrepreneurship. Private organizations are interested in finding new business opportunities; nonprofits look to expand their member base and their impact. The drive to accomplish these goals encourages participants in IPSPs to look for innovative solutions and make something different happen. Change and urgency are the hallmarks of many IPSPs. Public managers can share in these entrepreneurial efforts, participating in the creation of new approaches that might be sustained, often without government funding support.

- Adaptation and change. Business has to change and modify approaches in real time when something is not working correctly. Markets can change rapidly, and firms have to adapt to stay competitive. When IPSPs have business partners, changing plans when the original approach is ineffective or when resources do not match requirements is viewed as a sign of strength and competence, not misunderstood as poor planning and ineptitude, as it can be in the government.

- Leadership. IPSPs often have the support and active engagement of community leaders. Typically volunteering their time, community leaders contribute their own professional experiences, harnessing their management, organization, and people skills for success. Public managers can leverage the leadership within IPSPs to build community support and help promote their own government programs.

Disadvantages for Public Managers

IPSPs present challenges to public managers that can be a disadvantage over other forms of collaboration. These disadvantages are rooted in the voluntary nature of IPSPs, which ensures a level of impermanence that permeates their actions and approach:

- Difficult communications. The decentralized organization of some IPSPs can create difficulties for public managers to communicate with and engage participants effectively. There is no mandatory requirement for IPSPs to submit reports, hold regularly scheduled meetings, request approvals, or write memos. Governments have their own administrative cycles around budgets or public hearings, and the need for information about IPSP activities may be difficult to obtain and validate in a timely fashion.

- Unpopular politics. The self-driven nature of IPSPs means that they do not have to conform to the political positions of parties or elected officials. IPSPs may provide public services in a way that is unpopular or may attract negative political attention. In such circumstances, public managers have to worry about guilt by association.

- Impermanence. There is little that holds an IPSP together besides the faith of its members and their commitment to a cause. Participants in IPSPs can disperse as easily as they come together. Funding for IPSPs can be uncertain, and if it dries up, there may be no alternative funding to support its activities. Public managers need to approach IPSPs with uncertain futures with caution and not overcommit government reliance on IPSP activities to achieve their own agency’s goals and objectives.

- Mission drift. IPSPs are free to choose their own mission and the services they will provide. That mission can change at any time the participants feel that it is needed. IPSPs might change their mission because their participants have changed their priorities or based on the priorities of funders. Public managers should not always rely on an IPSP to provide the same services or provide them in the same way.

GOING GLOBAL

IPSPs have gained rapid acceptance as a preferred approach to address many global issues. The absence of global government and the difficulties associated with negotiating international agreements among many nations on problems that are highly interdependent and transnational make IPSPs an attractive alternative approach of global governance. A good example of a global IPSP that addresses global problems is the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN).

GAIN supports a vision of a world without malnutrition. Created in 2002, it is an alliance of governments, international organizations, the private sector, and civil society. Launched at a Special Session of the UN General Assembly on Children, GAIN supports collaborations to increase access to the missing nutrients in the diets of undernourished people. Its board of directors comprises leaders from government, industry, and nonprofits. An executive from the UN’s Children’s Fund is an ex officio member, but GAIN’s priorities are not set by any government organization.

GAIN creates national and regional business alliances of leading companies, which are exploring ways to bring high-quality, affordable fortified foods to those most in need, including the base of the pyramid: the poorest people. GAIN has entered into direct partnerships with a select number of companies and organizations to implement concrete projects with clear and measurable objectives (Forrer, Kapur, and Greene 2012).

The IPSPs like GAIN, and scores more like it, fill a serious gap between public services that are needed globally and the lack of administrative capacity in many countries to finance, produce, and deliver such services. With so many problems in the world, IPSPs offer an exciting opportunity for people to bypass the crippling effects of failed governments and organize efforts that can work to solve some of our biggest global problems.

CONCLUSION

Public managers often choose IPSPs when autonomy and innovation are valued above control and clearly defined roles and responsibilities. In this chapter, we reviewed the core characteristics of IPSPs and their differences with quasi-governmental organizations. We also provided examples of how IPSPs operate in different policy areas to further a discussion of how public managers can leverage the potential of IPSPs to serve the public interest. When public managers reach out to IPSPs, they inevitably face challenges in learning how to cooperate effectively.

Engaging IPSPs successfully requires public managers to approach collaborations in ways that are different from when the government is working with contractors or even when it is involved in a partnership or network. The need for new rules of engagement presents a new challenge and a new opportunity for public managers. Because IPSPs provide public services, interacting directly with the public, it is more difficult for public managers to determine firsthand if the IPSP is providing services that meet public policy objectives. For example, is the provision of services by the IPSP politically acceptable to citizens, and how can public managers collect data that may be important to the relevant government agency but are not collected by the IPSP?

The increasing frequency with which IPSPs are providing public services highlights a primary reason for government managers to be interested in collaborating with them: IPSPs can complement or supplant government efforts to provide services for their citizens. The examples outlined in this chapter demonstrate how IPSPs help communities reduce their effect on global warming, improve the development of transit-oriented development in congested areas, and reduce the overall costs of health care for at-risk populations. In an era of increasing fiscal constraints at federal, state, and local government levels in the United States, IPSPs offer enormous potential for government managers to broaden the scope and scale of services to citizens. By drawing from the private and nonprofit sectors, IPSPs mobilize financial resources, expertise, and organized interests around emerging societal problems and issues.

IPSPs do not offer the full range or level of public services that government policy requires, but they may be effective in providing public services in an innovative way to a select group of citizens or a highly specialized service to a neighborhood or community. In this way, they may be especially useful in providing services to groups or individuals that may be particularly expensive because they represent a small proportion of the total population or in providing a service to a community requiring special types of services.

The multisector characteristic of IPSPs challenges governments to better recognize and reconcile the interests of specific constituencies. Since IPSPs operate in a self-directed way, outside government, they often form to address the interests of specific social groups within the broader society. In Oregon, groups of citizens allied with universities and key businesses to address what they saw as pressing needs for greater protection of the natural environment than the standards set by government. Equipment manufacturers and a nonprofit representing first responders teamed up to develop innovative ways to quickly reopen critical roadways so disaster and emergency relief vehicles could get through. Local health care providers teamed up with insurance companies to identify and eliminate waste in health care costs. It could be said that IPSPs do what people would want the government to do if only the government would or could.