Chapter One

Dimensions of Cross-Sector Collaboration

For public managers, cross-sector collaborations (CSCs) allow governments to leverage funds, expertise, and risk sharing with other sectors that can provide key ingredients to the successful delivery of public goods and services. For nonprofit managers, collaborations allow their organizations to better meet their stated mission and possibly expand that mission to related areas of interest. For private sector managers, collaboration promises increased profits, enhanced reputation, and expanded business opportunities. All sector managers can benefit from a better understanding of the nature of these collaborations and how they are successfully led, managed, and governed.

This chapter begins by examining a dilemma facing all public managers: how to respond to global challenges with a public sector that lacks the resources and support to accomplish its public responsibilities. It also addresses the collaborative imperative, a confluence of factors that are driving governments toward networks and partnerships. Second, the chapter defines cross-sector collaboration and provides a framework of types and uses of such collaboration as well as key issues for the public manager. Each type of collaboration is explored in more detail in later chapters.

THE DILEMMA FOR PUBLIC MANAGERS

Governments at all levels—federal, state, and local, in both the United States and internationally—face enormous societal, governmental, and economic challenges that are likely to become even more complex. These challenges pose a dilemma for public managers: the gap between what citizens expect government to do and the resources and support to our governments have never been broader. Government is underresourced, undervalued, and underappreciated at the very time when there are so many challenges for efficient and effective government policies and programs.

The lack of confidence in government, built up over years of accumulated frustration, means there is scarce political support for enhancing government agencies and their performance. And the lack of resources that agencies receive, coupled with the expanding demand and the need for government responses to current and emerging challenges, means perpetuating ineffective government performance, which in turn reinforces the lack of confidence in government.

Governments at all levels frequently lack the expertise, capacity, or funding needed to identify emerging trends and adopt effective policies and procedures. As a result, public managers may need to depart from current governmental hierarchical structures and engage actors outside government, in the private and nonprofit sectors, to address the challenges we highlight in this chapter and other critical emerging policy concerns. Cross-sector collaboration is not the answer to all of today’s challenges, but it can become part of the solution if managers understand when collaboration is an effective alternative to government-only solutions and when they recognize the underlying tensions that exist between competing values that are important for protecting the public interest.

THE CROSS-SECTOR COLLABORATION IMPERATIVE

Public managers confront a complicated and difficult governing environment in which they are expected to carry out their duties and responsibilities. Markets, politics, and societal expectations are rapidly changing. Some of the changes stem from forces outside government, some are a product of a public sector that often seems largely dysfunctional, and some are the result of new forms of organizations that are emerging and becoming actors on the public scene. Today’s problems are more challenging than ever before, and yet governmental efforts to address those challenges seem more problematic than at any other time in recent memory. Thus, the challenges facing public managers “require concerted action across multiple sectors” (Kettl 2006, 13). A number of factors appear to be accelerating this cross-sector imperative.

Societal Transformations

Transformations in society and societal expectations often make it difficult for public managers to address new challenges, especially from a single agency or governmental perspective. Today we live in “a densely interconnected system in which local decisions and actions may trigger global repercussions—and vice versa—and the fate of communities in one region is bound to choices by decision makers elsewhere” (O’Toole and Hanf 2002, 158). Many different things move on globalized networks—people, products, data, money, flora and fauna, news, images, voices—faster, more cheaply, and to more places than ever before (Rosenau 1990; Scholte 2005; Wolfe 2004). Globalization compels public managers to look outside their traditional jurisdictional boundaries in an attempt to understand and solve the problems they face.

Increased global competition also is transforming what used to be thought of as a seller’s market, where power was held by the producers of goods and services, to a buyer’s market, where consumers have more choices. This has led many businesses to increase their focus on customer-centered practices. As a result, consumers have increased expectations of receiving excellent customer service from the firms and stores where they shop. When we order clothes, books, and household items online, we expect to receive what we wanted, and if we are not satisfied with the product, we expect to return it, no questions asked. With this growing expectation, public services that follow a more bureaucratic (and monopolistic) culture look even less satisfactory than before.

Major Challenges Require New Thinking

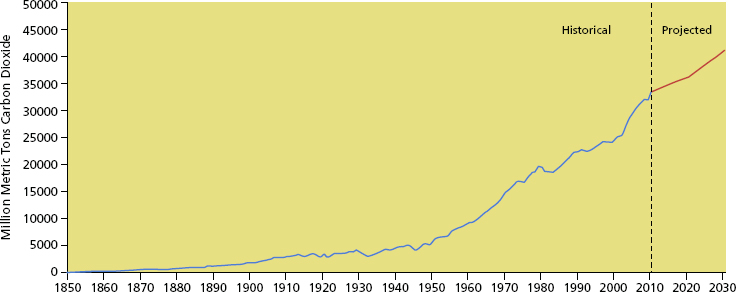

The list of major challenges for government is as numerous as at any other point in our recent history, encompassing such issues as deteriorating infrastructure, out-of-control health care costs, and climate change. Climate change provides just one clear example of a need for collaboration. The earth’s temperature is rising. Although some may debate the impact human activity plays in the rising temperatures at the earth’s surface and in the atmosphere (e.g., a combustion of fossil fuels for power and transportation, deforestation, and expanding livestock herds), none can debate that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have sharply risen in modern times (Pachauri and Reisinger 2008). Figure 1.1 provides a dramatic illustration of the problem.

Figure 1.1 Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1850–2030

Source: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2014).

The consequences of climate change are alarming: greater melting of ice at the earth’s polar caps and rising sea levels that threaten cities and nations. Global ecosystems will be altered, threatening the health or even survival of flora and fauna. Weather patterns are changing, and hurricanes and other storms are likely to become stronger due to warmer ocean temperatures. Diseases could also migrate with rising temperatures, possibly spawning global pandemics. Rising temperatures could mean dramatic changes in crop yields and production, threatening food shortages (National Geographic 2011; US Environmental Protection Agency 2011). Public leaders and managers will have to find methods for involving all sectors in addressing the causes and consequences of climate change.

A Dysfunctional Public Sector Environment

Despite the obvious need for an effective public sector, public attitudes about government, caused in part by the dysfunctional behavior of public officials, and public fiscal constraints, make public-only solutions nearly impossible. Americans’ confidence in their national government is at historic lows, according to Gallup’s annual governance survey. A poll conducted in October 2013 found that 81 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with the way the country is being governed, equaling the highest share since Gallup first asked the question in 1972 (Gallup 2013). Fortunately, public satisfaction with state and local government is significantly higher than that of the federal government, with 74 percent expressing a good or fair level of confidence in local government and 65 percent in their state government (Gallup 2012).

Over the past twenty-five years at the federal level, the public has witnessed a retreat from building rational, bipartisan policy consensus. By almost all measures of partisan polarization, the divide between Democratic and Republican members of Congress has deeply widened over the past twenty-five years, reaching levels of partisan conflict not witnessed since the 1920s and 1930s. Even the appointment of officials to lead government agencies is a victim of such partisanship. Presidential appointees now take longer to get approval than ever before, and more positions remain unfilled for long periods of time. The very functionality of government agencies is weakened, and qualified executives simply pass on taking a government position, unwilling to face the partisan public scrutiny and politicking that is often the price to pay for public service.

The fiscal health of most US governments is not good. In 2012, government debt at all levels was at record levels and budget deficits were commonplace. While fiscal conditions improved somewhat in 2013, many state and local governments are at or near their borrowing limits. Standard & Poor’s announced in August 2011 that it had downgraded the US federal credit rating for the first time ever, dealing a symbolic blow to the reputation of the world’s economic superpower.

Hollowed-Out Government

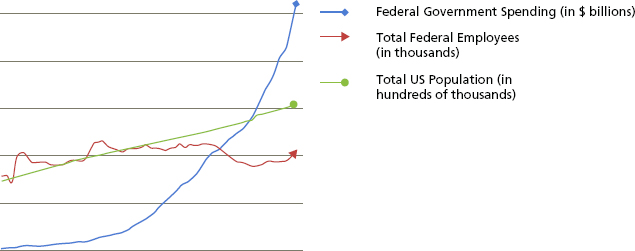

More than twenty years ago Mark Goldstein (1992) observed how sustained budget cuts for US government agencies and the rollback of regulatory authority had severely reduced their capacity to govern. At the time he cited Department of Housing and Urban Development and Food and Drug Administration scandals, the savings and loan bailout, and the Hubble telescope failure as proof of the damaging legacy of severe government cutbacks. He used the term hollow government to indicate the lack of resources to carry out government’s responsibilities. Figure 1.2 compares the growth in national spending and US population to the growth of federal civilian employees since 1948. Despite the increase in spending and population, federal civilian employment has not changed significantly since the post–World War II era. While increased government productivity due to technology may ameliorate this issue somewhat, much of what government workers do has limited potential for productivity gains. Of course, looking just at federal employment hides the full extent of federal government programs. More than a decade ago, Light estimated that the “true size” of government was substantially larger than the federal workforce when you counted federal contractors, state and local employees enforcing federal programs, and various grantees of federal funds (1999).

Figure 1.2 Federal Government Spending Versus Federal Executive Branch Civilian Employment and Total US Population, 1948–2009

Source: Newcomer and Kee (2011).

Note: Executive branch civilian employment excludes the Postal Service.

It was in the early 1980s and during the Reagan Revolution that public support began to ebb for maintaining the highest-quality workforce in federal government agencies. In the past thirty years, the nondefense federal workforce has remained at nearly the same level as it was during the period Goldstein was observing. Since that number includes significant increases for Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs, the workforce at other federal agencies has actually shrunk (US Office of Personnel Management 2011).

THE COMPLICATED ORGANIZATIONAL ENVIRONMENT

When governments struggle to find answers within their traditional bureaucratic structures, they often look to other sectors or new governmental forms to address the problem. The result of these emerging governance structures creates a more complicated organizational framework for public managers.

During the last half of the twentieth century in the United States, we saw three major trends:

- The creation of quasi-governmental structures that provide more latitude to managers than the traditional bureaucracy

- The growth of government contracting, in both the private and nonprofit sectors, as a method of delivering government goods and services

- Devolution of program responsibilities from the federal government to state governments

As we entered the twenty-first century, three new forms emerged to challenge traditional governmental structures: partnerships, networks, and a variety of independent actors, which we refer to as independent public-services providers (IPSPs). Some of these new structures complement and easily coexist with existing governmental structures, but many do not. Some networks and partnerships operate outside the traditional structures with a degree of independence that requires that public managers use nontraditional skills, such as in risk analysis and negotiations.

CROSS-SECTOR COLLABORATION: DEFINITION AND SECTOR ROLES

Cross-sector collaboration is the interaction of two or more of the three organizational sectors: the public sector (governmental units at all levels—local, state, and national), the private or for-profit sector, and the nonprofit or not-for-profit sector. Collaboration could include any combination of the three sectors, including public-private, public-nonprofit, private-nonprofit, or public-private-nonprofit. It is those collaborations involving the delivery of governmental goods and services that are the primary focus of this book. Many authors have articulated their own definitions of cross-sector collaboration. For this book, we build on the definition provided by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006):

Cross-Sector Collaboration is the voluntary linking of organizations in two or more sectors in a common effort that involves a sharing of information, resources, activities, capabilities, risks and decision-making aimed to achieve an agreed to public outcome that would have been difficult or impossible to achieve by one organization acting alone.1

Intergovernmental collaboration, while important, is not included in this definition because it does not refer to collaborations between sectors. National governments use a variety of tools, including grants and regulations, to encourage state and local governments to implement federal policy. The changing dynamics of collaboration in the federal system of government in the United States have received a great deal of attention (see Conlan and Posner 2008; O’Toole 2006; Derthick 1996; and Publius: the Journal of Federalism). State and local governments also enter into a variety of compacts and interlocal agreements to coordinate service among state and local governments. There is a considerable literature on this type of collaboration (see Brown 2008; Kettl 2006; Provan and Milward 1995). Interorganizational coordination among governments is critical, and lessons from those collaborations can inform cross-sector efforts. However, the focus of this book is on interactions among the sectors, not within them.

Also excluded are collaborations that are forced, which is why the definition includes the word voluntary. A business implementing environmental regulations is not an example of collaboration. However, if federal legislation permitted experimental approaches to reducing pollution and those experiments involved actions by more than one sector, then that might be an example of CSC.

In addition, excluded from this discussion are social enterprise organizations, except related organizations involved in delivering a public good or service. A social enterprise organization applies commercial efforts to improve human and environmental well-being rather than maximizing profits for external shareholders (Ridley-Duff and Bull 2011). Social enterprises can be structured as either for-profit or nonprofit and may serve a public purpose such as sustainability or economic development, but their primary goal is to provide private gains for the individuals who are involved in the enterprise.

Cross-sector collaboration may take many forms, from ad hoc interactions to complex partnerships or networks that may be glued together with contracts or other sophisticated agreements. In some cases, private or nonprofit organizations provide public goods and services in lieu of government provision. It is essential to understand the scope of sector actors involved in CSC. While there are some commonalities among the sectors, there also are significant differences in their missions, how they operate, to whom they are accountable, and how they measure success.

Public Sector

The public sector consists of entities organized and governed through some type of government-sponsored structure. In the United States, eighty-nine thousand governments are tracked by the US Census and constitute the public sector. This includes “general-purpose governments”: the national government, fifty state governments (and the District of Columbia), over three thousand county governments, nearly twenty thousand municipalities, and sixteen thousand towns. There also are fifty thousand single-purpose governments, such as school districts, utility districts, airport authorities, and miscellaneous quasi-governmental units. All public sector units operate under federal or state constitutional authority and applicable statutes. These governments range from the very small (e.g., a local community library district) to very large, such as the State of California, whose economy, if it were a nation, would rank eighth in the world, ahead of both Brazil and Russia.

Public organizations tend to be mission driven, and the process for the delivery of goods and services is an important element in their mission. Principles such as equity, citizen participation, and due process are sometimes as important as the final results. Public organizations are typically more constrained than either their private or nonprofit counterparts. Legislation, regulations, and judicial decisions all influence how public organizations operate. Public manager discretion is typically low, with too often an overemphasis on rules and procedures. Fortunately, some of the public sector reforms beginning in the 1980s have led to public organizations that are becoming more results driven as we shift from an emphasis on process to a greater emphasis on outcomes, as provided in the federal Government Performance Results Act, performance budgeting, and balanced scorecards (Newcomer 1997).

Private Sector

The private (or for-profit) sector consists of all individuals or organizations that provide goods or services with the goal of making a profit. In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service determines for-profit classifications, and there is an enormous diversity of organizations that operate within the private sector. Examples of for-profit entities include multinational corporations, such as Toyota, Marriott, General Electric, Apple, and Samsung; businesses designed to have a social impact (social enterprise organizations); family-run mom-and-pop stores; a variety of partnerships; and individual self-employed persons who generally provide a limited range of goods and services.

Private sector organizations are primarily driven by profit motivation; measures of success are typically financial measures such as profit, return on equity, dividends, stock price related to earnings, and market share. Financial measures are important because the private owners of these organizations are in competition for capital and customers. Private firms may exhibit corporate social responsibility by assisting their communities, becoming environmentally sustainable, and contributing to other worthy causes; but good corporate citizenship also is generally good for business. In the final analysis, however, private sector organizations are oriented toward a positive fiscal bottom line. They place a high emphasis on efficiency and entrepreneurial activity that can enhance their short-term and long-term fiscal situation and satisfy their customers, stakeholders, and shareholders.

Nonprofits

The nonprofit sector consists of organizations and associations that are organized for reasons other than to make a profit but are not governmental. A wide spectrum of organizations fits into the broad category of nonprofit organizations, and more and more public services are delivered through some type of collaboration with nonprofits. The trend is particularly prevalent in the area of human (or social) service provision. As of 2009, government agencies had approximately 200,000 formal agreements (contracts and grants) with about 33,000 human service nonprofit organizations (Boris et al. 2010). Working with government is the primary function of many nonprofit organizations, with over 65 percent of the overall revenue for human service nonprofits coming from the public sector (Boris et al. 2010).

Not all organizations classified as nonprofits in the United States provide human services, however. Nonprofits also consist of insurance companies, religious organizations, recreational clubs, arts organizations, business associations, cemetery companies, and a variety of other service organizations. This sector includes small neighborhood associations and churches, larger arts organizations (a local symphony orchestra, ballet, or opera company), and very large organizations such as the American Red Cross (in the United States) and the Red Crescent (in the Arab-speaking world). It also includes coalitions of such organizations. For example, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies is the world’s largest humanitarian organization, consisting of 187 members and a secretariat in Geneva (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies 2013).

Some nonprofit organizations are specifically created for educational and charitable purposes; in the United States, these organizations (nearly one million) are referred to as 501(c)(3) organizations (after the applicable section in the federal income tax code) and receive special tax status and are allowed to receive tax-deductible contributions from individuals and corporations. Internationally, nonprofit organizations are often referred to as NGOs. This sector collectively is also sometimes referred to as “civil society.”

Nonprofit organizations have a more nuanced bottom line than the private sector does. They are typically mission driven (as is the public sector) and place an emphasis on numbers of people served related to that mission. For example, Meals on Wheels, an organization that brings food to homebound individuals, measures its success by the number of meals delivered and individuals served. Nonprofit organizations have to maintain a balanced budget to stay in business, but they do not think about making a profit. Maintaining some budgetary surplus, however, is good for the long-term sustainability of the organizations. Surplus earnings can help to build institutional capacity in nonprofit organizations, strengthening fundraising departments or administrative divisions devoted to monitoring and evaluation. The challenge for many nonprofit organizations is that the program funding that they depend on often prioritizes program delivery and leaves little room for the institutional capacity building that can sustain long-term operations (Boris et al. 2010).

Nonprofit organizations also must meet the needs of donors, members of their organizations, and the clients they serve. Donor organizations such as foundations generally pressure nonprofit organizations to professionalize by promoting operating procedures and reporting structures in consistent formats that align with funding objectives. While members and donors normally are committed to the mission of the nonprofit, they may have additional goals that must be met, for example, participation in decision making or delivery of the services. Efficiency is important, but more important is how effective the organization is in meeting its mission and whether it is conforming to the principles of the organization, such as fairness, or service to a particular population of citizens. Finally, the increasing reliance on user fees in nonprofit service delivery, as high as 24 percent from private sources in 2008, adds pressure for nonprofit organizations to respond to the populations they serve (National Center for Charitable Statistics 2012).

While it may seem that these sector definitions are fairly exact, there is overlap among the sectors in terms of functions, approaches, and interactions with the public. Figure 1.3 provides an illustration of the sector’s roles and overlap.

Figure 1.3 Sector Roles and Intersections

While there are some roles that only the public sector performs (such as elections for public office, criminal trials, public health), other functions overlap the sectors. Thus, in the United States we have both publicly and privately operated utilities, as well as nonprofit cooperative utilities. Most housing is produced in the private sector, but we also have public housing authorities, and nonprofit organizations are involved in producing or managing low-income housing. Most arts organizations are organized as nonprofits, but many entertainment activities of similar nature (e.g., Cirque du Soleil, Broadway shows) are operated for a profit. We have for-profit television and the nonprofit Public Broadcasting Service. Attempts to delineate some activities as “inherently governmental” or “for-profit only” have not been terribly successful, as we examine more closely in chapter 3.

EMERGING CHOICES FOR PUBLIC MANAGERS

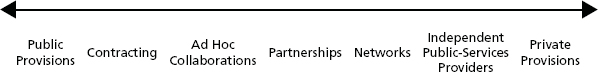

As the nature and extent of the public enterprise have changed, so have the choices available to public managers. We no longer automatically assume that if government has a role, that role must include public production and provision. Choices for public managers are a continuum, from full public production and provision to full privatization (and regulation) of the function, with a variety of arrangements in between. Figure 1.4 displays that continuum of choices. The choices between total public provision and full privatization are examples of CSC where government engages either or both the private and nonprofit sector in the provision and delivery of public goods and services.

Figure 1.4 Cross-Sector Collaborative Arrangements

There are advantages and disadvantages with each choice for public managers. As we move to the right on the continuum, government gives up some control over the good or service produced; CSC involves creating more autonomy for the actors, with full private provision removing government altogether from the provision equation. At the same time, in moving across the continuum, public managers are involving more actors, often creating a more innovative environment. In partnership and network arrangements, private and nonprofit actors are not treated as agents of government but as principals deserving of a voice in production decisions.

While these terms and choices of CSC seem discrete, in actuality there is often a blurring of distinctions, with public programs provided through a variety of these frameworks, including a number of hybrid arrangements. Furthermore, book and journal authors sometimes use the terms loosely or use analogous terms, adding to the confusion for public managers. For example, partnerships and contracting out might be viewed as a type of collaboration or even types of privatization. Partnerships are sometimes referred to as public-private partnerships (PPPs or P3s). Privatization is sometimes partial, as when part of a function is devolved to the private sector, or might be complete, as when government sells off a state-owned enterprise.

As the world becomes more complicated and problems become more challenging, public officials and managers need choices to engage other organizations outside government in the delivery of public services. Those choices need to be innovative and more flexible than the conventional approaches, such as direct provision by government or contracting out. The creation of new methods of public service delivery gives public managers a choice among a variety of policy and delivery tools (Salamon 2002).

CONSIDERING THE CHOICES

Public managers currently can select from these seven choices for delivering public goods and services:

- Direct government provision

- Contracting out

- Ad hoc collaborations

- Partnerships and public-private partnerships

- Networks

- Independent public-services providers

- Private provision or privatization

Excluded from significant discussion in this book are two of the possibilities that are first discussed briefly. The first is the ad hoc collaborations that periodically occur when government calls on the private or nonprofit sector to assist in a temporary project or emergency (Donahue and Zeckhauser 2011); the second is private provision or privatization, where government essentially vacates a policy or public delivery area, allowing the private or nonprofit sectors to provide those particular goods and services (Savas 2000).

- Ad hoc collaboration. Public officials invite private or nonprofit actors to participate in some public project or program, or those sectors might volunteer to participate. An example might be the creation of a new local park, where the public sector provides the land and certain basic infrastructure and private or nonprofit collaborators voluntarily provide certain amenities, such as sports fields, music forums, and other enhancements. While these arrangements pose interesting questions, such as transparency and private influence (Donahue and Zeckhauser 2011), they do not involve the ongoing interactions that are the hallmark of the CSCs discussed in this book, which raise the most significant challenges for public managers.

- Privatization (private provision). Government exits a particular function in whole or part, allowing that function to be performed, if at all, by private and nonprofit sector actors. Government no longer owns or supervises the function except through regulations or taxation. An example is the sale of state-owned enterprises, such as occurred in Britain under Margaret Thatcher, when utilities, housing, airline companies, and other public assets were sold to the private sector. This option is largely a political decision to lessen the role of the public sector in the nation’s economy. Although it is important in nations with a significant number of state-owned enterprises, it is not an option that most public managers will address or influence.

Primary Choices for Public Provision and Cross-Sector Collaboration

This section briefly describes and discusses the five choices representing the primary options available to public managers, ranging from the most traditional, direct government provision, to the latest incarnation of CSC, IPSPs. We do not claim that these five options cover all possibilities, but they represent basic models public managers may use, each with basic characteristics, differences, expectations, tensions, and implications.

Direct Government Provision

Public officials develop a program and assign it to an agency or create an agency to deliver it. The program is therefore delivered primarily through public sector workers directly to citizens eligible for the program. Direct provision of public services by the government continues to be the mainstay for many government functions. Examples include government agency inspectors, such as food safety, and environmental regulation compliance; state and local safety and security functions, such as police, fire, and medical emergency; recreation and park services; water and water treatment; and public education (Bowman and Kearney 2011).

Contracting Out

Public officials determine that some or all of a public function could be provided at less cost by private or nonprofit actors. The public sector defines the parameters of the good or service, and the contractor provides the service based on those parameters. Examples of public contracting include such simple necessities as office supplies to very complex products such as the development and construction of major defense systems. Contracting out also has become more common in areas that used to be considered (and in some circles remain) the exclusive domain of government (Verkuil 2007). For example, some state department of motor vehicle functions are contracted out, and the Transportation Security Administration contracts out some security screening at sixteen US airports, the largest being San Francisco International Airport.2 Contracting out is the topic of chapter 3.

Partnerships

Public officials engage a private sector organization or a nonprofit organization in the joint production of public goods and services where certain aspects of the production and provision are shared, such as planning, design specifications, risk, and financing. In a partnership, the public manager is working primarily with one other party. However, the variations in the types and forms of partnerships are numerous (Wettenhall 2003). Growing in popularity are partnerships involving infrastructure projects, where the private sector might agree to fund, build, own, and operate a facility for some period of time in exchange for a return on its investment—paid by either users or by the government. Partnerships and PPPs are discussed in chapter 4.

Networks

Public managers use “formal and informal structures, composed of representatives from governmental and nongovernmental agencies working interdependently to exchange information and/or jointly formulate and implement policies that are usually designed for action through their respective organizations” (Agranoff 2003, 7). The difference between a partnership and a network is the number of actors: networks involve the public sector with more than one other actor from the private or nonprofit sector. Many human services programs are operated through networks that include a variety of governmental and nongovernmental organizations. Networks are a new and curious configuration of governance for most public managers and are organized in a variety of forms (Koliba, Meek, and Azia 2011) that are discussed in more detail in chapter 5.

Independent Public-Services Providers

An emergent type of collaboration is the IPSP, a term we are using to describe entirely new entities that are attempting to meet unfulfilled public needs. Nonprofit and for-profit actors jointly develop an organization or framework to address public problems outside the traditional hierarchical structure in government. IPSPs are formed through a collaboration of principal actors; they are not agents of government.

Independent public-services providers are self-directed entities composed of businesses, nonprofit organizations, and governmental units that collaborate in the production or delivery of public goods or services but operate outside the sphere of government control and oversight. Increasingly they are being established out of a recognition that governments have become unable to respond adequately to serious public policy challenges. While individual characteristics of IPSPs may be familiar, it is their combined characteristics that make them singular and allow them to have a unique relationship with the government. We believe these are the most significant characteristics:

- They are largely self-directed and are able to act independently of government.

- They comprise multiple stakeholders who provide the organization a sense of legitimacy.

- They provide public goods and services, acting in place of government.

Consider these three diverse examples of IPSPs:

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation: The Family Homelessness Project (2013) consists of a network of public and private partners to address the long-term needs of homeless children and families in the Puget Sound region.

- AidMatrix (2013) helps coordinate humanitarian relief among more than forty thousand business, nonprofit, and government partners. It provides web-based, supply chain solutions that work in the harshest field conditions.

- The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases (2013), an initiative of the US-based Sabin Vaccine Institute, works with international partners to break down the logistical and financial barriers to delivering existing treatments to the people who need them most.

Each of these IPSPs is distinctive in its mission, approach to solving problems, and relationship with its partners. In contrast to government employees and contractors, always enmeshed in the government hierarchy, IPSPs are sometimes linked to a traditional government framework, for example, through funding, and at other times have no specific linkage to government. In either case they act with a greater discretion and autonomy because they are outside the governmental bureaucratic framework, even when the government is involved. Because of the autonomy of IPSPs, public managers do not have the same control that they might over other arrangements.

Illustrating the Five Choices: Public Health Programs

To briefly illustrate those choices, we examine a common public service: public health.

- Direct governmental provision. Governments directly provide health services through a variety of programs. The federal Veterans Health Administration operates hospitals and clinics for veterans, states or counties have hospitals for those with mental health disabilities, and many cities operate public hospitals. All of these are funded with public dollars and staffed by public employees with the expectation that direct public provision is less expensive than private health care or that direct provision is necessary to provide services to a population that otherwise would not be served.

- Contracting out. Governments have determined that certain public health functions can be contracted out to reduce the cost of service. Some city hospitals have been contracted out to a private provider that operates and manages them. In these cases, personnel might be a mix of public and private sector workers. In instances where the local government has sold the facility to a for-profit or nonprofit health care provider, the workers are private (although many would be former employees of the hospital and therefore former government workers). Government may contract for certain services, such as care of indigents or emergency room operations, where the private or nonprofit sector may not be able to recoup costs; in this case, government might pay based on service provided.

- Partnerships. Partnerships in the health care industry are common. They range from the use by the federal government of private providers in Medicare (for seniors aged sixty-five and over) to the use by states of various health maintenance organizations to provide services for those eligible for Medicaid (the federal-state program for low-income individuals). Partnerships typically occur because expertise and functionality exist in the private sector, so it makes sense to use the private sector in the delivery of these services instead of maintaining or developing a separate public capacity to provide the same services. Such partnerships often provide greater choices for the citizens served.

- Networks. Networks in health care are common. The Small Communities Environment Infrastructure Group (discussed in chapter 5) is an illustration of a consortium of public, private, and nonprofit organizations designed to assist local communities in the design and funding of clean water and wastewater programs. Networks allow the combining of expertise from a number of different sources and sectors to bring to bear on the problem at hand.

- Independent public-services providers. IPSPs are emerging in response to health care needs that are not being met by government programs. The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases, discussed in more detail in chapter 6, is an example of a program funded and operated by a consortium of private and nonprofit organizations to fight tropical diseases that do not receive much attention from government programs.

Examining the Trade-Offs

There are advantages and disadvantages with each method of collaboration. For example, government has complete control when it defines, produces, and provides the public good or service (public provision). As we move to the right on the continuum, there is less government control as other actors become involved. At the extreme right is privatization or private provision, where government is completely removed from the provision equation and only indirectly controls, if at all, through the regulatory and taxation process. In giving up control, government may achieve other important objectives, including greater efficiency, more innovation, greater targeted service, and growth of the private sector. As we move to the right, government also must operate in a greater collaborative environment, and the intensity of the collaboration is likely to increase. Thus, as with many other choices, public managers may have to decide which competing interest or value is most important and then decide whether and how to use the various approaches.

As public servants move to the right on the continuum, they also are embracing multisector solutions that involve multiple organizations in a network of policy actors or implementers. This new environment involves collaboration and mutuality and is organized around a heterarchy, or web of actors in a variety of horizontal relationships that exist outside the traditional government hierarchy (Kettl 1997; Kee and Newcomer 2008). Instead of a public administration based on traditional hierarchical notions of accountability, public servants must negotiate agreements with actors over whom they may have less leverage or no direct control, but instead are connected through contractual or other arrangements in horizontal relationships that involve the development of reciprocal trust and mutual accountability. In heterarchical relationships, government must exercise control through contract monitoring, performance measurements, after-action reports, citizen engagement and feedback, or other means to ensure that their contractors, network partners, and others involved are performing in a manner that meets public expectations.

Finally, moving from direct provision and a traditional contracting arrangement to CSC means moving from the traditional principal-agent to a principal-principal relationship. In public provision, public servants are agents of elected policymakers (the principals), and in contracts, contractors are agents of public managers; both of these are traditional principal-agent relationships. In partnerships and networks, however, private and nonprofit actors are principals with their own goals and objectives, and negotiations become more nuanced and balanced. While there may be some agency involvement (e.g., in developing a contract), the nongovernmental actors traditionally have more control over how they operate, and the development of goals, objectives, and measurements is typically a joint activity, not one in which government dictates to its agent. Finally, with IPSPs, public managers are dealing with fully autonomous organizations over which they may have little leverage and or control.

Table 1.1 provides an illustration of additional characteristics among the four CSC methods in contrast to public provision.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Approaches to Delivery of Public Goods and Services

| Approach | Government Provision | Contracting Out (Traditional) | Partnerships/PPPs | Network | IPSP |

| General approach | Direct provision by government-employed workforce | Government hires private or nonprofit provider | Mutual production, usually under a defined agreement | Varied production by members of the network according to individual strengths | Production by an independent organization with significant discretion |

| Relationship to government | Government provides funding, defines process, and hires personnel. | Government writes the request for proposal and issues a contract based on defined criteria. | Government is a partner, with a specific role that may include funding, monitoring, or even joint production. | Government may be the network administrator or central coordinator; it may provide funding; or it may simply play a supplemental role. | No relationship, or government may play a secondary role; it may be a funder but is not the exclusive source of revenue and the IPSP is not totally dependent on government. |

| Relationship to citizens | Government provides direct contact and provision. | Contractor may provide the direct contact and provision. | Either or both partners interact with the public, depending on their agreement. | Diffused, multiple contacts from network partners. | IPSP provides direct contact and provision as needed. |

| Trust required among actors | Low: traditional checks and balances | Low: contract monitoring | Medium: frequent interaction among partners under legal parameters set by the agreement | High: multiple points of contact and working together; limited government oversight | High: multiple points of contact and working together without government oversight |

| Key issues or tension | Efficiency, capacity, and government failure | Contract design and monitoring | Public interest versus interests of partners; agreement on outcomes | Convergence of multiple interests and outcomes | Ability to influence outcomes and protect public interests |

The descriptions provided in table 1.1 make clear that choosing the best option is based on a variety of factors. The relationship to the government takes into account the role it will play in directing and controlling the public services being provided. Direct provision gives government maximum control. As we describe more fully in chapters 3 through 6, each of the other choices in sequence reduces government’s ability to specify and dictate the services to be provided and requires a different approach by public managers with respect to leadership and accountability. The choice of using an IPSP means that governments will play only a secondary role in defining and directing what services are provided, how they are provided, and individuals’ eligibility to receive them.

Choosing an approach has implications for the relationship of the service provided with citizens as well. Except when government directly provides the service, all the other choices involve some entity other than the government that provides services to citizens. Having the service provided by public employees may best ensure that government is responsive to its citizens. When someone else provides a service, direct accountability is reduced. This can raise questions and potential protests by people who do not want to deal with government contractors or others.

The third factor that relates to relationships is trust. IPSPs and networks require a high level of trust between government and their collaborators. Since government has less influence in networks and IPSPs over the specifics of the service delivery, it must have great confidence that collaborators will carry out activities as expected and in good faith. Partnerships and PPPs also require trust, but there generally are legal provisions within the partnership agreements to ensure that performance meets expectations. Trust is a minimal factor in traditional contracting out, as it is assumed vendors will present their capabilities honestly in their proposals and adhere to their contractual obligations. The contract itself will ensure compliance.

Each of the choices poses significant issues for public managers. Public managers are more familiar with the issues and tensions around government provision and traditional contracting out. However, as public managers seek to choose collaborative options, new issues and tensions arise. Can the public manager ensure an outcome in the public interest? Can the managers recognize the legitimate interests of their private and nonprofit collaborators and still effectively articulate an overriding public value or result that is the expected outcome of the collaboration?

Private and nonprofit organizations are capable and credible actors in the provision of public goods and services. When collaborating with government, they present to public managers an important option for improving the quality of such goods and services and citizens’ access to them. Of course, governments have long made use of the capacities of business and the nonprofit sector to help achieve government policy and program goals and objectives, typically through specific contracts for the products and services that government needs or wants to deliver. However, the growth and popularity of arrangements such as partnerships/PPPs and networks suggest that they also are expanding collaborative mechanisms of choice.

Today public managers have many options, and partnerships/PPPs and networks can be found at all levels of government:

- Yuma Desert Proving Grounds is a unique partnership arrangement between General Motors (GM) and the US Army Enhanced Use Leasing (EUL) Program. The public-private partnership resulted in GM constructing a new proving ground on federal land. GM and the EUL share use of the facilities and jointly advance vehicle testing (National Council for Public-Private Partnerships 2009).

- Indiana Economic Development Council is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that serves as a statewide economic development agency. Its membership consists of a network of all entities within the state that are involved in economic development, including representatives from all sectors (Agranoff 2003).

- Rainforest Alliance uses the power of the market to ensure profit for both business and local communities through a variety of partnership arrangements with governments and business. The alliance strives to conserve biodiversity while ensuring sustainable livelihoods (Rainforest Alliance 2013). It operates outside governmental structures and directly with business and other nonprofits.

- Drug Abuse Resistance Education, created in Los Angeles in 1983, is a network advocating substance abuse prevention. The program brings police officers into classrooms to deliver necessary skills to students to prevent drug use, gang involvement, and violence (Milward and Provan 2006).

- City of Dallas/Dallas Public Library is a developmental partnership agreement between the City of Dallas and the Kroger Company, which developed a library in a strip shopping center. Library attendance rose while more people were similarly brought to the neighboring grocery store as they both benefited from shared services (National Council for Public-Private Partnerships 1999).

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (2011), created in 2002, is an independent public-services provider that supports public-private partnerships to increase the amount of nutrients in the diets of people around the world. It has already worked with more than six hundred companies in twenty-five countries, reaching an estimated four hundred million people.

As government solutions move away from programmatic silos toward structures that involve the public, nonprofit organizations, and the private sector, public managers need different management skills from those honed in traditional hierarchical structures. Although the exact shape and extent of the emerging heterarchy is not fully defined, it is evident that public managers are moving toward a networked or partnership approach to service delivery that involves organizations from all sectors. In such a heterarchy, “authority is determined by knowledge and function—through horizontal linkages rather than the traditional hierarchical form of vertical authority” (Kee and Newcomer 2008, 10). Sometimes these horizontal linkages are forged through contractual arrangements with government as chief funder and coordinator. At other times, public managers must negotiate with entities over which they have little control.

CONCLUSION

Public managers have several choices in the way in which public services may be delivered. However, they face constraints as well: budgetary, legal, and political. As innovative forms of CSC have emerged to join the more familiar modes of direct provision and contracting out, it is critical that public managers understand how to choose among these options to provide the best public services possible.

In some ways, these five primary choices can be viewed as evolutionary and a reflection of broader efforts by practitioners, scholars, and public managers to innovate as new challenges present themselves and conventional public service delivery choices prove to be inadequate. The expanding number of issues public managers are trying to address, the complexity of both the problems and possible solutions, the limitations of available public funding, and the rapid pace of change have all motivated those inside and outside government to discover and invent more effective ways of providing public services and of providing those services in a way that is more responsive to people’s preferences and circumstances.

An overview of the steady evolution of the five public service choices and their presumed advantages and potential disadvantages is provided in table 1.2 and will be discussed in more detail in succeeding chapters.

Table 1.2 Transition Through the Five Basic Options

| Capacity | Services | Presumed Advantages | Potential Disadvantages | |

| From government to contracting out | Same capacity | Same services | Cheaper | Loss of control |

| From contracting out to partnership | Expanded capacity | Better services | Technical and management expertise | Capture by partner |

| From partnership to network | Expanded capacity | Responsive services | Technical and management expertise Local preference insights | Diffused accountability Difficult to gain consensus |

| From network to IPSP | Expanded capacity | Enhanced services | Technical and management expertise Local preference insights Innovative problem solving | Lack of government oversight Policies may conflict with government priorities |

Deciding to contract out instead of directly providing services is based on a classic make-or-buy decision. It poses the basic question of whether it is better to rely primarily on the use of internal public resources to provide some goods or services (make) or rely on vendors outside the government (buy). While the services are intended to be the same, they are contracted out when they can be achieved more efficiently. However, contracting out results in some loss of control by government managers, and success is tied to how effectively the contract is written and monitored.

The need for additional capacity and access to greater technical and management expertise and access to capital has pushed governments to work in partnership with business, typically through various PPPs. Such partnerships are created to improve existing services or create new services that would be difficult for the public sector to manage alone. At the same time, private and nonprofit partners have different goals from government that must be reconciled. Private partners are primarily motivated by profit; thus the potential for capture by the private partner or excessive compensation must be addressed by the public manager.

PPPs often raise issues of fairness and whether a full representation of community interests has a voice in the PPP. When broader community expertise is needed, particularly information about local conditions and preferences, and when broader political support is sought, a network approach is useful and effective. Networks allow a variety of voices and multiple actors to address a public problem. But more actors also have a tendency to diffuse accountability. Managers must work to gain consensus on network objectives and measurements.

Finally, government may support an independent public-services provider when an entity exists that already is providing the services needed to solve a public problem. The independence of the IPSP can foster more creative and innovative problem solving. However, public managers often have limited oversight of IPSPs, and their independent nature may lead to policy directions that are contrary to existing government policy.

The five options offer public managers different approaches to delivering public services. Each of these approaches offers unique advantages but also places different expectations on the collaborators and different requirements for public managers to ensure success. Using these five options in a way that promotes the efficient and innovative delivery of public services means public managers must understand how to align public service delivery with the best option.

Some of these options are relatively new to public managers, or they may have limited experience in knowing how to use them successfully. This book is designed to encourage public managers to consider innovative options that could be beneficial in the public interest. The following chapters describe these choices in more detail, examining what they are, how they are different from the other choices, and their advantages and disadvantages. Public managers must learn how to analyze these tools effectively and under the right circumstances if they are to improve public service delivery.