Chapter Five

Network Governance

Networks involving public, private, and nonprofit organizations are becoming a familiar form of collaboration through which public managers can more effectively address public policy issues. A logical progression in the evolution of the forms of collaboration, networks are more inclusive and diversified than PPPs and other cross-sector partnerships. They extend a long-standing approach to collaboration—informal government cooperation with private and nonprofit organizations—to more formalized multisector arrangements. Networks are more commonly found in the areas of human services delivery and response to disasters, but increasingly they are being used in other areas of public service delivery, such as job training and local economic development, and are increasingly adopted to address global issues (Hale and Held 2012).

Governments that use networks to deliver public services address a concern that is often expressed about PPPs where the principal participants in that type of collaboration are between government and the private sector. Critics have attacked the use of PPPs as being overly deferential to business interests and letting the private sector have too large a role in matters of public governance. One response by public managers to the negative public perceptions of PPPs has been to look for collaborations that expand the number of partners and engage networks that offer a more diverse representation of stakeholders and interests in the community, including nonprofits, community groups, schools and universities, and religious organizations. Private sector interests and values are counterbalanced by the more civic-minded culture of other organizations. As we have argued elsewhere, businesses will embrace a social responsibility mind-set and make decisions that advance the public interest, but the popular public perception typically casts business in a far narrower, self-serving role.

The attractiveness of networks as a form of collaboration for public managers is based on one assumption and one presumption. The assumption is that other organizations, in the private sector or the nonprofit sector (or both), have something of value to offer government in developing and delivering public services that are superior to what government could provide alone. Typically networks have the potential to offer public managers access to diverse and sophisticated sets of capacities, experiences, resources, and technologies that are not otherwise resident in most government agencies (Lee and Liu 2012). They also can contribute the experiences and expertise of private and nonprofit executives and managers. Finally, network members may be in a position to contribute to or directly fund activities, or the network itself may be able to attract funding support from charitable foundations or other sources of grant funding.

The presumption is that government can effectively coordinate its efforts with other organizations—private, nonprofit, and other government agencies—and work together more efficiently to deliver public services that are in the public interest. The presumption that public managers can effectively collaborate with networks is the chief subject of this chapter. In chapter 2, we described briefly how businesses and nonprofits have greater experience with collaborations and are highly motivated to establish further collaborations with government in the form of networks. Of course, many government agencies cooperate with other public organizations and have informal, if not regular, interactions with other entities outside government. However, most public managers have limited experience in the practice of using networks to meet their own program’s goals and objectives. In this chapter, we discuss how public managers can examine potential networks, identify the unique characteristics of networks, and develop leadership and management approaches that can best support the network in achieving public purposes.

Moving beyond the bilateral relationships of cross-sector partnerships and engaging multiple participants to work together for a common cause has several implications for public managers. In a network, each member contributes efforts or resources, or both, toward a shared goal. Such an arrangement requires coordination of efforts between the network members, such that they share in discussions about what to accomplish and how to accomplish it, in what might involve a deliberative process. It also means creating mechanisms for open exchanges of information, emphasizing transparency so all parties in the network are able to voice their opinions and resolve issues to improve coordination and trust among members.

Of course, there also are instances of networks that public managers fall into and therefore have little voice in their design. In some areas of social services, the growth of the nonprofit sector in human services dictates that government engage a number of providers if they are to promote more holistic services. To effect change in childhood obesity, for example, federal authorities have taken a network approach by leveraging government and nonprofit youth services organizations that already serve targeted populations. In other cases, public managers must engage in ad hoc networks of local government agencies and departments to provide immediate relief, as in the immediate aftermath of a major natural disaster (Kapucu and van Wart 2006). Our focus in this chapter is on the purposive decisions that public managers take to develop and select network participants for specific types of public services.

DEFINITIONS

Working in a collaborative relationship with several organizations at the same time is easy to understand, but it is much less easy to define what constitutes a “network” as a formal arrangement of collaboration. According to Milward and Provan (2003, 2006), networks are collaborative, not bureaucratic, structures that involve autonomous organizations, often responsive to a broad range of nongovernmental stakeholders, while also working interdependently with both government and other network participants. Networks that governments use are collections of organizations that carry out activities on behalf of the public interest for a shared purpose. They are often orchestrated or coordinated by a public manager rather than directed by the manager. A key feature of network governance is the recognition that members work both collaboratively and independently at the same time. Our focus is on networks that involve government and are directed toward some public purpose rather than business alliances, policy networks, or nonprofit-to-nonprofit networks.

A network is a loose confederation; members join together to take collective action in which they share common interests but retain the primacy of their actions that will protect and advance their own interests. What actions a member is willing to take in concert with the others reflects in good measure his or her calculus of the consequences for his or her own interests and what can be gained through the collaboration. Working both collaboratively and independently makes perfect sense for members of networks, but it also renders network governance a tremendous challenge because individual members are continually weighing their own interests against the collective interests of the group.

For public managers, effective network governance means collaborating to formulate and implement government policies that are cost-effective or bring greater value to the constituents served. A distinctive nature of networks, where members’ roles and contributions to the effort are a matter of negotiation, is that they are subject to change depending on the effectiveness of the network activities and alternatives available to members. Network governance requires good management skills on the part of the public managers and the creation of coordinating mechanisms across network members that are very different from those that are effective for managing programs in a government agency (McGuire 2002, 2006; Silvia and McGuire 2010).

Networks may present a double-edged sword to public managers: the more diverse the interests of the network members are, the richer the assets are to which public managers can gain access. At the same time, diverse network membership makes it all the more challenging to find common ground for action. However, much can be done to cultivate a shared purpose that unites network members despite their diversity. The key is identifying a fundamental value or desired result shared by all members of the collaboration and developing a method of validating it with one another through the collaborative process. The collaborative process (network governance) used to build agreement by members around what the network should do is itself a critical factor in building strong and committed networks. In some cases, that shared vision is facilitated and agreed on through the terms of the network’s funding, such as a federal grant program that supports state and local actors addressing an at-risk community. In other cases, like emergency management, the vision is communicated as an overall need for a community to recover and prove resilient in the face of a major natural disaster.

One critical factor is the nature of the problem being addressed. When networks are formed to address a simple goal (albeit a critical one), the means for accomplishing the goal are straightforward, and shared expectations for the network members’ contributions are clear so they can operate smoothly. Of course, the opposite is also true: governing networks that take on complex problems, where best practices are not confirmed and roles for members are unclear, can easily lead to problems. Similar to other forms of collaboration discussed earlier in this book, much of the challenge of network governance involves understanding the individual interests of different network members and how to negotiate those interests with respect to wider collaborative goals. Often the challenge is to communicate to network members how their individual interests can be better served by working together, such as the benefit to local businesses by cooperating with government to assist communities in rebuilding after a major disaster.

HOW NETWORKS FACILITATE COLLABORATION

Networks address different purposes for government and are organized with different types of structure out of either design or necessity. Understanding the role of the public manager and network governance involves first understanding the type of network that the manager is working with. The function or purpose of the network will influence the type of interest that individual members bring to the collaboration, the type of coordination required, and the overall measures for determining if the network is doing what it is supposed to be doing. The following sections review some of the different purposes that networks are organized around.

Types of Networks

Networks are formed in many ways and perform many functions. Four classifications capture dominant roles that drive different types of networks. While some networks may operate with more than one of these functions, one of these four typically indicates the dominant approach of the network (Agranoff 2007):

- Informational. Partners come together almost exclusively to exchange information about agency policies and programs, technologies, and potential solutions. Any changes or actions are voluntarily taken up by the individual organizations themselves.

- Developmental. Partner information and technical exchanges are combined with education and member services that increase the members’ capacities to implement solutions within their home agencies and organizations.

- Outreach. In addition to the activities of the developmental network, the network partners develop blueprint strategies for program and policy change that lead to an exchange or coordination of resources. Decision making and implementation are ultimately left to the agencies and programs themselves.

- Action networks. Partners come together to make interorganizational adjustments, formally adopt collaborative courses of action, and deliver services, along with information exchanges and enhanced technology capabilities.

State and local governments have effectively used networks for decades to deliver a variety of human services programs. Examples include job training networks, health care and community care networks, community development networks, family and children’s services networks, and local economic development networks (Turrini et al. 2010). The need for government agencies to coordinate the delivery of multiple social services for one person or family makes networks a natural form of governance in this arena. To illustrate the different ways networks can organize to deliver human services are four different types of networks providing social services for the homeless (Moore 2005) that align with the four types described above:

- Informational—Children and Homelessness Collaborative, Glendale, California. The primary focus of the Glendale Homeless Coalition is to have different agencies within the city work together to assist homeless individuals and families. Building on that focus, the collaborative has not only increased community awareness about the needs of homeless students but also fostered a better understanding of the different origins of homelessness through learning about different cultures and practices, leading to closer agency relationships and improved services for students and families. The information exchange improved service delivery by increasing understanding of homeless people’s needs, but there was no joint action. Each agency acts on its own, based on its understanding of the information generated by the network.

- Developmental—Coalition for the Homeless, Pasco County, Florida. Several years ago, the Coalition for the Homeless of Pasco County recognized a lack of affordable transitional and emergency housing, as well as a need to disseminate information regarding available services for the homeless. Acknowledging that one agency could not provide all services needed, the coalition created the Housing and Urban Development Continuum of Care that now includes public, private, and faith-based agencies. It developed a formal memorandum of understanding with shared funding by the agencies. The collaboration supports ongoing services and specific projects such as the point-in-time homeless count. Each agency provides particular services as determined by its funding. The network increased its members’ information and resource capabilities, but there was no pooling of resources in a joint program.

- Outreach—Perspectives, St. Louis Park, Minnesota. A nonprofit agency, Perspectives has served at-risk and homeless children since 1991. It offers an after-school program with academic, social, and nutritional components and a supportive housing program. Perspectives’ staff approached the St. Louis Park School District and proposed a collaborative effort. The two entities coordinated their strategies and jointly applied for and were awarded a grant under the federal McKinney-Vento Act and then invited public, private, nonprofit, and faith-based social service agencies to partner with them. Those involved in health, housing, transportation, community education, parks and recreation, and the police were asked to join the collaboration. Target provides financial support, and General Mills supplies financial and volunteer support. Within the school district, the US Department of Education Title I coordinator and the homeless liaison were key participants, along with principals, teachers, and adjunct staff. In this case, Perspectives reached out to the St. Louis Park School District to develop a broader strategy for at-risk and homeless children, but implementation was addressed by each member of the network.

- Action networks—HEART Program, Spokane, Washington. Representatives of the Spokane School Districts sought to provide a quality academic atmosphere along with addressing other necessities such as housing, medical care, and clothing for their homeless students. They convened a task force to create a new vision for the program. The task force included representatives of the school district, YWCA, three universities, shelters, the school board, and the Spokane human services agency, along with the three teachers from the school. Based on the vision set out by the task force, the HEART (Homeless Education and Resource Team) Program was created as an integrated support model to refocus efforts on education. In this case, a fully integrated joint program was established.

The four models provide useful illustrations of how networks differ in the scope of their efforts and the scope and intensity of their collaboration. Some networks are more about cooperating (informational), while others involve deep integration (action). One advantage for the public manager in understanding the different types of networks and their functions is to set reasonable expectations for what participants should be working on and trying to achieve. Of course, it would be anticipated—especially when funding is uncertain—that networks change their activities and levels of collaboration over time in response to the demand for their services and the resources available to fund them. A network that begins as informational, for example, may evolve into one structured around action if the environmental conditions demand that type of transition.

Structure of Networks

Another way to understand how networks facilitate collaboration is to compare different structures for organizing networks and the implications of structure for the relationships among members. In the most decentralized structural form, participants are equal partners and have an equal voice in network activities. Even in such flattened structures, it is clear that some members of a network will be more influential than others and the relationships between participants and their exact roles will differ. For instance, members of a network who work part-time for a local nonprofit may feel intimidated or even offended by the business-style approach a participant from a large corporation might take at meetings. Network governance means identifying and accommodating different styles of the members and cultivating a governance approach that supports the overall aims of the network.

Network structure also has a direct impact on the overall effectiveness of networks (Turrini et al. 2010; Provan and Milward 1995). Along with the influence over shared goals and trust in the network, the structure can influence the stability of the network and how resilient the formal relations are to changes in the surrounding environment (Provan and Milward 1995). Three dimensions of structure that can be understood from formal relations are interconnectedness, cohesiveness, and centralization.

Provan and Kenis (2008) identify three distinctive structures (or modes) employed in network governance (see figure 5.1). Understanding these three forms can help public managers recognize the types of networks they are in and the associated implications for governments based on their structural characteristics. The three structures also present different models that can influence the design of networks for public purposes.

Figure 5.1 Modes of Network Governance

Source: Provan and Kenis (2008).

In some cases, public managers can promote a structure of network governance that best suits the needs of the government agency. For example, it is sometimes best for the government agency to offer leadership and direction for establishing the network’s functions, as was the case of the National Incident Command in the weeks and months following Hurricane Katrina. Other times public managers will want to play the more limited role of convener and let the energy and interests of network members set the tone and ambition for the network. Whichever way it evolves, the structure of the network will have profound implications for the amount of influence a public manager will have in its governance.

A description of three examples of networks, each reflecting a different type of network structure, is provided in the following sections.

Shared or Self-Governed Network

In 1990, the Small Communities Environmental Infrastructure Group (SCEIG) was formed in Ohio as an association of federal and state agencies, local governments and groups, service organizations, and educational institutions in order to assist small communities in meeting their environmental infrastructure needs, such as safe drinking water and wastewater systems. Members include the State of Ohio Water Development Authority, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, US federal-state Extension Service at Ohio State University, US Department of Agriculture/Rural Development, US Economic Development Administration, private lending representatives, university rural centers, nongovernmental organizations, and regional development districts.

This group of experts has quarterly meetings to discuss the needs of small communities and what responses or remedies are appropriate and feasible. In addition, the SCEIG has compiled a list of documents, publications, and Internet resources for the use of small communities in considering the financing, installation, repair, or expansion of environmental infrastructure. The goal of the network is to assist small communities in identifying the most appropriate resources that can help them with the difficult task of developing, improving, and maintaining their water and wastewater systems. To this end, the network established three committees to address the most pressing needs of small communities: Finance Committee, Curriculum Committee, and Technology Committee.

The network was convened by the State of Ohio Water Development Authority, which served as the initial lead organization for the network in its early days. Over time it has evolved into a shared governance model whose purpose is largely informational and outreach.

Lead Organization Network

The San Diego County Office of Education (SDCOE) and its school and community partners organized a network to address the response to and recovery efforts from wildfires. Strong Santa Ana winds channel through mountain passes in the area and create gusts approaching hurricane force. The combination of wind, heat, and dryness turns the chaparral found throughout the region into explosive fuel. Due to the winds, the wildfires are highly unpredictable, more so than wildfires that occur in other parts of the nation.

The October 2007 fires were the largest in San Diego County history; an estimated 515,000 county residents were evacuated. The fires resulted in ten civilian deaths, twenty-three civilian injuries, and ninety-three firefighter injuries. More than sixty-two hundred fire personnel fought to control the fires. In September of that year, the SDCOE had gathered resources to set up its Emergency Operations Center (EOC). On October 22, 2007, the day after the fires started, SDCOE staff arrived in the EOC. The EOC served as a gathering place during the emergency, coordinated information resources and response and recovery actions across the school districts, and served as a point of contact for interfacing and coordination with other agency EOCs throughout the county. The SDCOE’s superintendent had twice-daily calls with the forty-two district superintendents to generate a task list for the SDCOE. An SDCOE staff member served as liaison with the Operation Area Emergency Operations Center, the Red Cross, and sheriffs’ departments for gathering information over the phone and using a real-time, web-based emergency management system.

The network was created to support a better approach to emergency response. The collection and distribution of information to network members and others improved reliability and timeliness. Access to the information facilitated quick decision making and the coordination of the decisions based on the information available. The network was supported by several staff, reflecting the need to use resources to ensure the efficient operations within the network itself. It is notable that the EOC was part of a larger regional network: a network within networks (US Department of Education 2008).

Network Administrative Organization

Fairfax County’s Department of Systems Management for Human Services (DSMHS) was given the responsibility for facilitating the coordination of human services delivery in Fairfax County, Virginia. County leadership determined a need to streamline its social services during a time of rapid population growth, demographic changes, and expanded human resource needs, which included in-migration of refugees from other nations.

The original vision of county leaders was a fully integrated client intake system, with DSMHS serving as a lead organization in a broad network that would include federal, state, and county programs of assistance and available assistance through a variety of nonprofit actors in the county. The DSMHS failed to achieve that goal because of the difficulty of gaining sign-off from state and federal officials, concerns about privacy, and other issues that primarily involved protecting agency turf.

DSMHS implemented a coordinated service planning system that matched the needs of county residents with services available in the county from public, private, and nonprofit agencies, creating a network of human services providers. It played more of a network administrator role, providing coordination and information but not fully integrating the actions of the various agencies in the network.

This effort was complex due to the number of actors involved, including county human services agencies, state and federal agencies, and both private and nonprofit providers of human services in the county. It was important to involve all key stakeholders in the planning and implementation effort. In this way, DSMHS was able to achieve widespread buy-in to the concept and improve overall delivery of social services to populations in need.

The Fairfax County case demonstrates two possible roles of government in a network-led organization: lead organizer and network coordinator. Rather than directing activities, determining what roles others might play, and ensuring these roles and responsibilities through contracts, governments can play many different roles, depending on the way the network is organized. Initially DSMHS sought to play a lead organizer role in the network, but practical and legal objections led to a network coordinator role that has worked effectively.

It is important to note that a network may evolve from one classification to another over time, as was the case with the Fairfax County network. Such was the case of the network established by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to address the emergency needs created by Hurricane Katrina, where the roles and influence of members changed over time. When the storm hit, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was only three years old, and FEMA had never before responded to a category 5 hurricane, which led many to argue that the system’s infrastructure and individual expertise were not at all equipped for the storm. Due to the unprecedented nature of such a catastrophe, DHS and FEMA had little to no institutional knowledge to draw from in crafting a response, putting them at a disadvantage during the crisis (KSG 2006). The resulting intergovernmental network began as rather decentralized, and gradually assumed more of a lead organization model as federal authorities asserted more influence over the situation.

THE PUBLIC MANAGER AND SUCCESSFUL NETWORKS

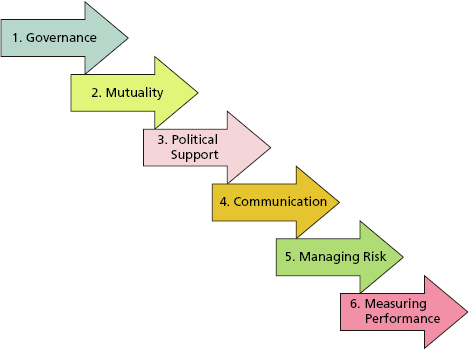

We have grouped the factors of successful network governance from the perspective of a public manager under six broad categories illustrated in figure 5.2. The following sections describe each of these elements.

Figure 5.2 Elements of Network Governance

Governance

Networks may be designed in many ways. Provan and Kenis (2008) identified the three possibilities already displayed in figure 5.2. Whatever design is chosen for the network, it must accommodate the expectations of the network participants and facilitate the functions the network is to perform. Most often government is in a role of a lead organization or will act as network administrator, as in the Fairfax County Human Services case. Sometimes government assumes a lower-profile role, as in a self-governed network, where it is just one of many actors but can still exert its influence on the scope and activities of the network.

Regardless of the structure, network managers need to develop and communicate a common purpose that will encourage participants to act on behalf of the interests of all collaborators. Public managers may need to be directly involved in designing the networks to ensure that occurs. In either case, public managers must facilitate working relationships with external groups, recognizing their needs and interests. However, such relationships cannot be simply informal or convenient. The process requires more than monitoring, consultation, and reacting to proposals. It requires a recognition that the network will need to grow and learn together. It means public managers need to shift from being excellent “bureaucratic responders” to innovative “partner creators” (Agranoff 2012).

Mutuality

A public manager thinking about creating a network must consider the array of associations that might be involved: nonprofit organizations, small businesses and multinational corporations, local volunteer groups, substate planning agencies, public-private ventures, international organizations, and others. The question is how to find the right balance of organizations that bring value to a network yet have a shared interest in its efforts and outcomes. The participants must be convinced that the time and effort spent creating and developing a network is worth it; there must be a payback for them. The dilemma, however, is that sometimes it may be necessary to invest the time in building a network before the potential gains are clear.

When in a collaborative mode, public managers should account for the concerns of their own organization as well as those of potential collaborators. The shared purpose of the network is achieved in such a way that all participants can claim achievements for their own organizations. The achievements may be the kind that participants want to make public, such as an increase in the number of people receiving services. That type of publicity can improve an organization’s reputation and help it with future fundraising. The achievements may be the type an organization would want to keep in-house, such as meeting influential people who might be contacted in the future and be a resource for other issues of importance to that participant. Successful networks find a way to achieve both the shared goals and the individual aspirations of individual participants.

Political Support

If participants harbor suspicions that the efforts of a network may be criticized by public officials or political support withdrawn, network governance may end up being more trouble than it is worth. The desire by elected officials for a strong government role in networks to ensure accountability is an understandable position, consistent with traditional views of public management. Yet the virtues of networks are their flexibility, innovativeness, and an expanded capacity over what government agencies can offer when acting unilaterally. Ultimately public managers need to represent the prospects for network success to elected officials by clarifying their expectation of how government participation in networks will improve public service delivery. Network members themselves can be effective lobbyists on behalf of the network and its cause. The support for the effort by well-regarded organizations and people in the community can be useful in allaying political concerns and building political support for the network.

The creation of networks also can be an initiative launched by a public official or government executive. Enthusiasm for networks among top managers may not reflect a full understanding of the complexity of the mission. Executives may not recognize gaps in skills or technical knowledge needed for effective network governance. The result could be an initiative that taxes public managers with an idea that sounds good but is difficult or even impossible to execute. In such cases, network participants can be a direct source of support for the public manager. They bring their own stakeholders and (sometimes) funding, which can be leveraged to garner the support of public officials.

Nothing breeds success like success. Garnering political support for a nascent network or managing the new responsibilities and expectations for a new initiative is a challenge. When there is clear interest in solving a problem, networks can be initiated and then mature as they operate. Other networks take time to develop, creating new working relationships, convincing people of the merits of collaboration, and discovering the shared goals and objectives among the participants. Delivering better public services and gaining support from participants is the best way to create political support.

Communication

Networks function best when there is an open flow of information among the parties (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone 1998). Deliberations are more successful when all of the parties are engaged and better informed. Public managers need to develop a variety of skills and procedures to facilitate that exchange. Communication protocols that are established help build trust among the network participants. Effective network governance is built on good relationships, which in turn are built on trust, and trust is founded on open and reliable communications.

In building high-quality relationships in networks through communities of linked professionals and practitioners, both inside and outside government, public managers face practical challenges. Learning to communicate openly in networks requires the capacity to create and use knowledge through informal exchange and mutual engagement. Information and communications technology are essential tools because partners often are situated in disparate locations. However, they are not a substitute for face-to-face contact but a parallel to collaborative work, allowing not only the linkage of dispersed participants but also interactions with many potential and actual collaborators.

Managing Risk

Public managers are used to managing the risks associated with the activities of their agency. Certain procedures or precautions undertaken by public managers may seem unnecessary to those who work outside government, because they do not always understand how actions associated with a government agency may be viewed by elected officials or public media. Network members may not always act with the same sensitivities and considerations that public officials would employ, thereby putting public managers at risk of criticism of the network over which they may have no direct control.

As with any other collaboration, public managers share in the risk of a failure of others in the network to perform. It is useful for managers to understand the capabilities of the network participants and the challenges they face in maintaining their own operations and making long-term commitments of resources to the network. Will or can government step in to fill the void? Are other network partners available to substitute for the one that has been unable to fulfill its role in the network?

Public managers also must manage the risk that their own agency will not meet its promises to a network. Government budgets may not be approved or could be cut after they have been authorized. Everyone knows that bureaucracies move slowly, and public managers may have difficulty getting other government agencies to act quickly enough to meet network requirements. Networks that can align the activities of participants that are well established and funded will be easier to create and maintain.

Measuring Performance

Measuring network performance will depend on the purpose of the network’s formation. For a network formed to respond to a natural disaster, performance could be based on meeting goals and objectives faster and with greater reliability. For example, SDCOE was successful in moving information about wildfires more quickly to those who could then pass it along to others and make decisions based on that information. When networks have a limited and clear role to play, measuring improvements in terms of outputs is best.

Networks that have more complex, integrative operations, such as Fairfax County’s DSMHS, would choose factors that reflect their broader goals. The DSMHS chose percentage of needs met as one of its performance measures. It is also critical that performance measurements align with the functions the network was created to carry out. Agranoff’s four types of networks—informational, developmental, outreach, and action—set expectations for what the participants want the network to accomplish, and performance measures should reflect that function. Public managers will want to deter others from assigning performance measures (and therefore expectations) to a network that has not been agreed to by the participants.

Turrini et al. (2010) suggests the following measures of network effectiveness: client level of effectiveness, network capacity of achieving stated goals, network sustainability and viability, community effectiveness, and network innovation and change. Thus, the performance of a network is not based on simply how well information is shared or that action is improved; it also depends on the overall operations and functions of the network itself. Network managers must address the needs of specific clients and the network’s stated goals, but attention also needs to be paid to the viability of the network. Is the network vulnerable to changes in political priorities, research constraints, or other variables, or is it something that can adjust to these changes? The extent to which the surrounding community supports and assists the network also will influence its effectiveness. Finally, the ability of the network to innovate and adapt to change will influence both network longevity and the quality of services it delivers to the public.

Within the context of network effectiveness, the overall performance of networks should be considered in terms of both functions and institutional structure. Measuring the performance of networks in this way involves assessing their operational achievements in the short term, as well as their structural ability to integrate into communities and provide some lasting support to the clients they serve.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF NETWORKS

Networks are just one option among the choices public managers have for engaging in cross-sector collaborations (CSCs), and they have unique advantages and disadvantages compared to other forms of collaboration. As we have discussed, networks are diverse in the ways they organize, the types of problems they address, the complexity of those problems, and the extent to which government agencies participate in service delivery. As a result, the advantages and disadvantages we describe are not equally applicable to all networks.

Advantages

The advantages networks can offer public managers as a CSC are discussed throughout this chapter. We have consolidated some of the central ones and summarized them here. Of course, these advantages will be realized only when network governance is effective.

Cutting Across Silos

Some types of public services are delivered using multiple programs or services that need integrating, such as those of Fairfax County’s DSMHS. Others pose complex issues that call for analyzing and understanding multiple factors at one time, such as those of Ohio’s SCEIG. Still others require rapid response times and precise coordination, such as those of San Diego County’s SDCOE. In each instance, improving the delivery of public services required efforts that transcended one office, one mission, one sector.

Insular bureaucratic protocols often constrain public managers to operate within narrow silos and to direct their agency’s efforts and resources toward a limited set of actions. Networks cut across these silos and facilitate a collaboration that helps participants see more clearly where their own organization’s efforts contribute to achieving a larger impact. With such a perspective, it is easier for public managers and other network participants to adjust their approaches and activities in ways that result in better public services.

Leveraging Resources

As governments find themselves under spending constraints, any one agency is unlikely to have all of the necessary skills, resources, and abilities to provide public services comprehensively and at the optimum level of quality. Businesses and nonprofits share the experience of government not always having enough funding or the right skills to meet their own organization’s goals. At the same time, businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies have different ways of looking at issues; different mixes of skills, experiences, and resources available; and different approaches to addressing issues in their respective fields.

Collaborating in a network brings together organizations that can leverage their own resources with those of other network members and increase their overall capacities to take action. By unifying these varied skill sets, networks give all participants the opportunity to widen the scope and scale of their own organization’s activities, particularly when engaging distinct cultures.

Greater Transparency and Citizen Participation

Networks thrive on the exchange of information among participants, which facilitates coordination among network members. In turn, that same cooperation and communication mean greater public access to information about agency operations, policies, practices, and performance. Many aspects of a government’s operations remain a mystery to the public. Even simple requests for copies of government contracts seem nearly impossible without a great deal of effort and struggle. Sharing information within the network about past and future activities, performance successes and failures, and budgets and spending provides a greater chance of that information getting out to the public.

In contrast to PPPs, networks thrive on engaging and integrating many perspectives and leveraging diversity to provide better public services. The diversity of stakeholders and interests in a network can also translate into greater political support from public officials and citizens. Citizen participation is enhanced by networks in two ways. First is through the roles citizens play as volunteers for nonprofits. Nonprofits involved in networks provide a point of access for their members, who can learn about network activities through their own organizations. Second, as citizens express their views and preferences on the priorities of the organizations they are associated with, those same preferences are expressed in network deliberations.

Innovation

By bringing together diverse resources and perspectives, networks become centers of innovation where new ideas are offered and considered. Most large organizations, whether public, private, or nonprofit, tend to favor routines and established practices. Networks offer participants an opportunity to take a fresh look at how public services are being delivered and imagine how they might be improved, without the discussion being viewed as a direct challenge to accepted practices.

Thus, one of the attractions for people to participate in networks is the diversity of perspectives and experiences available. Networks can foster a sense of excitement about the possibilities of doing something new and different. They offer participants an easy way to learn about new ideas they can share with their home organizations.

Knowledge Transfer

Networks spread information faster and more easily than in other governance arrangements and provide many avenues for the transfer of information among participants. Learning from the experiences of others in networks can also lead to a behavioral change within the observing organization.

Networks are an invaluable source of program-related knowledge and experiences from other managers working in the field. Knowledge about past successes and failures also surfaces in network deliberations. Frank discussions of failures in public service delivery are a valuable learning experience and are more likely in a network, to the benefit of all participants and the network itself.

Disadvantages

Using networks as a form of collaboration, as with any other approach to governance, has disadvantages as well.

Less Accountability

A principal characteristic of networks is their decentralized operations, which allows them to be responsive and flexible. But networks are not always adept at providing the information or using a unified chain of command for accountability purposes. Networks may not have to confront difficult accountability issues when all is going well, but who becomes responsible for failing or underachieving networks? Who decides what the performance standards should be? When networks have volunteer organizations among their ranks—sometimes exclusively—how are they expected to respond to criticism from public officials or the media? Setting performance standards and collecting the data needed to make accurate assessments is challenging.

Less Stability

The very diversity that is a network’s strength is the source of a possible lack of stability. Networks have to simultaneously balance external pressures from interest groups and internal pressures from within their organizations. Participants who are excited over forming a network might lose enthusiasm and decide to drop out, upsetting the balanced interests of the collaboration. Are there other participants to fill in? Will they have the same interests in outcomes? How will the change affect the network’s group dynamics? Participants moving in and out of the network—particularly when one participant has been accommodated by the network, only to have it leave—disrupt network operations. The potential instability can be a deterrent to some organizations that may be considering joining the network.

Cost of Formation

One potential problem in forming networks is the intensive time and effort needed to create them. Many reform efforts involving networks can take years to create, and significant results may not be produced during the initial years. Every administrative hour spent on CSCs is an hour taken away from internal management issues. Government agencies may not have the personnel available or the free time to dedicate to the creation of networks. While the promise of better service delivery makes networks attractive, the time and effort have to be invested up front, without any guarantee of success. The time spent on a network that falls apart could be viewed, in retrospect, as wasted cost and effort.

More Complex Governance

The governance of networks is far more complicated than that of PPPs or cross-sector partnerships. The multiple organizations and their multiple goals, the diverse personalities of the leaders, the varied access participants have, and the willingness to share resources are only a few of the factors that public managers must try to align and direct toward a shared goal and its achievement. Of course, the conditions and circumstances under which these are done are themselves dynamic and subject to change, both gradual and sudden. The blending of interests together into a collaborative whole from such a diverse set of interests can overwhelm public managers as they attempt to institute good network governance. The key is understanding the level of involvement and intervention that is required by network members, particularly public managers, to coordinate network activities. Because networks are decentralized and often less formal, there is greater potential for dissensus among member goals. The less formal the relations of a network are, the more work public managers will have to coordinate and to align network activities.

Network Capture

Networks operate outside traditional government boundaries. If they are not governed properly, different interest groups could manipulate the goals and activities of a network for their own gains and to the disadvantage of people who have not organized a network or are excluded from it. Networks could use their access to government agencies to claim legitimacy for operations that are harmful or fraudulent. Just because a network has been formed to deliver public services does not mean it will act in the public interest. It is the responsibility of the public manager to ensure that networks are legitimate representatives of the relative community of interests and act in the broader public interest.

OVERCOMING CHALLENGES TO GOOD NETWORK GOVERNANCE

In the effort to explain networks and communicate their potential efficacy, public descriptions of how they are created and operate can be overly optimistic. We have described the advantages and disadvantages of collaborating using networks. In the real world, the number of successes using networks is likely matched by as many stalemates or failures to launch. We suggest some commonsense approaches public managers can take when creating networks that will assist them in overcoming barriers to their formation.

Lead with Purpose

Launching a network with a clear purpose and plan for government’s role makes it easier to engage potential partners and bring them together in a shared cause and with a shared purpose. Leading with a clear purpose not only inspires people to do better, but sends a message that change is coming and it has the support of top leadership. Promoting a vision of change encourages people who want to see change and signals that they will be supported within the organization.

Secure Buy-In from Partners

Network participants need to believe that their interests and concerns will be given fair consideration. Uneven power relationships within a network are inevitable, but who has the power within the network to set agendas and make decisions is a critical issue for all participants. Mary Parker Follett’s concept of “power with” (discussed earlier in the book) offers the best possible use of power in collaborative arrangements. If public managers see their role as blending their own power bases with those of their collaborators, the network will be stronger and more effective.

It is best not to identify network solutions too early or compel the network to reach a consensus too soon. Participants have their own ideas about the nature of problems the network could address and what actions could be effective. Allowing the network to endorse one approach supported by one participant before a full deliberation may undermine success. Establishing an open discussion and a deliberative process is critical to ensuring that participants have a voice and believe they will reap specific benefits for their organization and themselves. Such a process does not mean networks have to move slowly, but they do need to move deliberately with openness to pluralistic thinking.

Be Opportunistic

Networks present numerous challenges on how best to organize and govern. Building a network around an issue or problem that people agree needs immediate attention will make it easier to solicit cooperation. It is one reason that networks have been able to form so quickly around natural disasters. Once a network is formed and has proven itself useful to the participants and has a track record, it is easier to make the case for a long-term commitment to partici-pating in the network and it opens up the door to expanding the issues that could be addressed collaboratively.

Pick Good Leaders to Participate

Not all executives who lead or work in organizations may be good candidates as participants in a network. Successful collaboration means a willingness to help advance the common purpose and interests of the network, sometimes at the expense of a more specific interest of a participant’s own organization. Network leaders must convince others that support for shared network goals will end up advancing the goals of the individual participants, more so than if they operated on their own. Leaders who can take such an approach tend to recognize that trait in others, and there is a comfort in working with people who are perceived as “honest brokers” and “trusted partners.” Networks need participants who are willing to act collaboratively and not use their role in the network to hinder its progress by seeking to retain the status quo or unfairly promoting their own organization’s interests.

A public manager’s decisions to participate in CSCs should include systematically thinking through whether they have the agency resources (e.g., staff time and budget) that will likely be needed and can afford to assign appropriately skilled staff to represent their agency and its interests. It may be helpful to use a memorandum of understanding, which clarifies the expectations and commitments associated with participation in a CSC.

GOING GLOBAL

Networks have gained rapid popularity as an approach to addressing some of the most difficult global policy challenges. The task of developing a consensus among national governments in the form of treaties or international protocols grows more difficult as globalization expands and intensifies the interdependence of nations. International organizations such as the World Bank and the United Nations confront these challenges as they look to design and implement programs and policies that address development issues such as described by the United Nations Millennium Development Goals.

The global governance landscape is becoming more crowded with expanded roles for multinational corporations and global nongovernmental organizations, which are becoming directly involved in solving global problems. Global networks have sprung up to fill a global governance gap across a range of policy areas. The absence of a global government that has full authority to regulate and enforce policies means that global networks tend to operate with greater independence and the government plays a less directive role. One example of a global network is the Global Fund (Hale and Held 2011).

The Global Fund is dedicated to attracting and disbursing resources for fighting HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, supporting collaboration among governments, civil society, and the private sector. The Global Fund was established as a result of a 2002 UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS, which underscored the need for increasing funding to combat HIV/AIDS. Since its creation, it has become the main source of funding for programs fighting AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. The directing board is composed of representatives from all sectors—businesses, donor and recipient governments, affected communities, and civil society. As an organization combating global disease epidemics, the Global Fund brings together many aspects of global society while it faces many challenges, such as funding and cooperation with participating countries.

CONCLUSION

Networks present a choice on collaboration that is very different from PPPs, partnerships, and contracts. The change from essentially a bilateral relationship to a multiparty collaboration expands the possibilities for aggregating interests across the private and nonprofit sectors in order to devise and implement a better way to deliver public services. At the same time, it adds layers of complexity involving network governance.

For many types of public services, PPPs and partnerships provide the right form of collaboration. When the type of public service needed has been clearly identified but the best way to deliver it is unclear, bilateral collaborations can achieve the innovation desired while developing a governance model that involves fewer transaction costs for public managers. However, preexisting conditions or the complex nature of a problem may necessitate a larger number of organizations in a given cross-sector collaboration. Many nonprofits already operate in areas of human service delivery, for example, and networks may be preferred over partnerships because of the reality that so many organizations already exist in the operating environment around the policy area of interest. In addition, networks may be necessitated by the complex nature of a social issue being addressed, such as childhood obesity, emergency management, or mental health care.

As we have illustrated in this chapter, networks have different structural characteristics and different purposes, which lead to different priorities for governance. They can address a straightforward problem—distributing information quickly to facilitate responses to natural disasters such as fires in San Diego—or a highly complex global problem—addressing the global threats of HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. They can be launched as a high-level international initiative—like the World Commission on Dams (United Nations Environmental Programme 2001)—or as a practical effort to improve human services for the homeless in Pasco County, Florida, or social services in Fairfax County, Virginia. The complexity of the issue addressed has a direct impact on the structure of the network and the associated transaction costs of managing the relationships among the involved members. Understanding broad classifications of network structures and purposes can help public managers adapt their own governance approaches to coordinating action, trust, and overall effectiveness and performance within the network collaboration.

Managing networks calls on an administrative capacity that is beyond the typical set of management skills needed for working in government. The potential for networks to provide public services in more innovative and more responsive ways than direct government services, contracting, or PPPs demands attention to the types of administrative capacity needed to develop and coordinate these types of networks. Demonstrated successes of networks in any policy area are some of the most important means for sustaining political support for network approaches to service delivery. Recognizing network structures and functions, adapting elements of success in network governance, and measuring results will communicate successes and can lead to a better integration of network governance into the work of public administration.