Chapter 2Advanced Operators

Solutions in this chapter:

Operator Syntax

Operator Syntax introducing Google’s Advanced Operators

introducing Google’s Advanced Operators Combining Advanced Operators

Combining Advanced Operators Colliding Operators and Bad Search-Fu

Colliding Operators and Bad Search-Fu Links to Sites

Links to Sites

Introduction

Beyond the basic searching techniques explored in the previous chapter, Google offers special terms known as advanced operators to help you perform more advanced queries. These operators, used properly can help you get to exactly the information you’re looking for without spending too much time poring over page after page of search results. When advanced operators are not provided in a query, Google will locate your search terms in any area of the Web page, including the title, the text, the Uniform Resource Locator (URL), or the like. We take a look at the following advanced operators in this chapter:

intitle, allintitle

intitle, allintitle inurl, allinurl

inurl, allinurl filetype

filetype allintext

allintext site

site link

link inanchor

inanchor daterange

daterange cache

cache info

info related

related phonebook

phonebook rphonebook

rphonebook bphonebook

bphonebook author

author group

group msgid

msgid insubject

insubject stocks

stocks define

define

Operator Syntax

Advanced operators are additions to a query designed to narrow down the search results. Although they re relatively easy to use, they have a fairly rigid syntax that must be followed. The basic syntax of an advanced operator is operator:search_term. When using advanced operators, keep in mind the following:

There is no space between the operator, the colon, and the search term. Violating this syntax can produce undesired results and will keep Google from understanding what it is you’re trying to do. In most cases, Google will treat a syntactically bad advanced operator as just another search term. For example, providing the advanced operator intitle without a following colon and search term will cause Google to return pages that contain the word intitle.

There is no space between the operator, the colon, and the search term. Violating this syntax can produce undesired results and will keep Google from understanding what it is you’re trying to do. In most cases, Google will treat a syntactically bad advanced operator as just another search term. For example, providing the advanced operator intitle without a following colon and search term will cause Google to return pages that contain the word intitle. The search term portion of an operator search follows the syntax discussed in the previous chapter. For example, a search term can be a single word or a phrase surrounded by quotes. If you use a phrase, just make sure there are no spaces between the operator, the colon, and the first quote of the phrase.

The search term portion of an operator search follows the syntax discussed in the previous chapter. For example, a search term can be a single word or a phrase surrounded by quotes. If you use a phrase, just make sure there are no spaces between the operator, the colon, and the first quote of the phrase. Boolean operators and special characters (such as OR and +) can still be applied to advanced operator queries, but be sure they don’t get in the way of the separating colon.

Boolean operators and special characters (such as OR and +) can still be applied to advanced operator queries, but be sure they don’t get in the way of the separating colon. Advanced operators can be combined in a single query as long as you honor both the basic Google query syntax as well as the advanced operator syntax. Some advanced operators combine better than others, and some simply cannot be combined. We will take a look at these limitations later in this chapter.

Advanced operators can be combined in a single query as long as you honor both the basic Google query syntax as well as the advanced operator syntax. Some advanced operators combine better than others, and some simply cannot be combined. We will take a look at these limitations later in this chapter. The ALL operators (the operators beginning with the word ALL) are oddballs. They are generally used once per query and cannot be mixed with other operators.

The ALL operators (the operators beginning with the word ALL) are oddballs. They are generally used once per query and cannot be mixed with other operators.

Examples of valid queries that use advanced operators include these:

intitle: Google This query will return pages that have the word Google in their title.

intitle: Google This query will return pages that have the word Google in their title. intitle: “index of” This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title. Remember from the previous chapter that this query could also be given as intitle:index.of, since the period serves as any character. This technique also makes it easy to supply a phrase without having to type the spaces and the quotation marks around the phrase.

intitle: “index of” This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title. Remember from the previous chapter that this query could also be given as intitle:index.of, since the period serves as any character. This technique also makes it easy to supply a phrase without having to type the spaces and the quotation marks around the phrase. intitle: “index of” private This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title and also have the word private anywhere in the page, including in the URL, the title, the text, and so on. Notice that intitle only applies to the phrase index of and not the word private, since the first unquoted space follows the phrase index of. Google interprets that space as the end of your advanced operator search term and continues processing the rest of the query.

intitle: “index of” private This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title and also have the word private anywhere in the page, including in the URL, the title, the text, and so on. Notice that intitle only applies to the phrase index of and not the word private, since the first unquoted space follows the phrase index of. Google interprets that space as the end of your advanced operator search term and continues processing the rest of the query. intitle: “index of” “backup files” This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title and the phrase backup files anywhere in the page, including the URL, the title, the text, and so on. Again, notice that intitle only applies to the phrase index of.

intitle: “index of” “backup files” This query will return pages that have the phrase index of in their title and the phrase backup files anywhere in the page, including the URL, the title, the text, and so on. Again, notice that intitle only applies to the phrase index of.

Troubleshooting Your Syntax

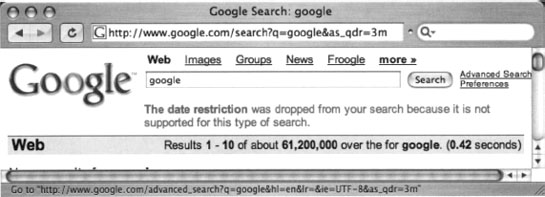

Before we jump head first into the advanced operators, let’s talk about troubleshooting the inevitable syntax errors you’ll run into when using these operators. Google is kind enough to tell you when you’ve made a mistake, as shown in Figure 2.1.

In this example, we tried to give Google an invalid option to the as_qdr variable in the URL. (The correct syntax would be as_qdr=m3, as we’ll see in a moment.) Google’s search result page listed right at the top that there was some sort of problem. These messages are often the key to unraveling errors in either your query string or your URL, so keep an eye on the top of the results page. We’ve found that it’s easy to overlook this spot on the results page, since we normally scroll past it to get down to the results.

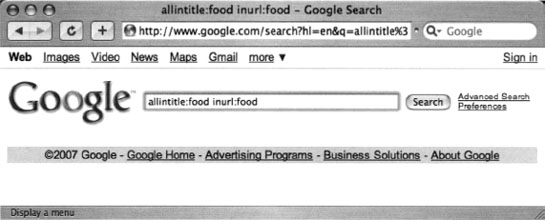

Sometimes, however, Google is less helpful, returning a blank results page with no error text, as shown in Figure 2.2.

Fortunately, this type of problem is easy to resolve once you understand what’s going on. In this case, we simply abused the allintitle operator. Most of the operators that begin with all do not mix well with other operators, like the inurl operator we provided. This search got Google all confused, and it coughed up a blank page.

As you grom in your Google-Fu, you will undoubtedly want to perform a search that Google’s syntax doesn’t allow. When this happens, you’ll have to find other ways to tackle the problem. For now though, take the easy route and play by Google’s rules.

Introducing Google’s Advanced Operators

Google’s advanced operators are very versatile, but not all operators can be used everywhere, as we saw in the previous example. Some operators can only be used in performing a Web search, and others can only be used in a Groups search. Refer to Table 2.3, which lists these distinctions. If you have trouble remembering these rules, keep an eye on the results line near the top of the page. If Google picks up on your bad syntax, an error message will be displayed, letting you know what you did wrong. Sometimes, however, Google will not pick up on your bad form and will try to perform the search anyway. If this happens, keep an eye on the search results page, specifically the words Google shows in bold within the search results. These are the words Google interpreted as your search terms. If you see the word intitle in bold, for example, you’ve probably made a mistake using the intitle operator.

Intitle and Allintitle: Search Within the Title of a Page

From a technical standpoint, the title of a page can be described as the text that is found within the TITLE tags of a Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) document. The title is displayed at the top of most browsers when viewing a page, as shown in Figure 2.3. In the context of Google groups, intitle will find the term in the title of the message post.

As shown in Figure 2.3, the title of the Web page is “Syngress Publishing.” It is important to realize that some Web browsers will insert text into the title of a Web page, under certain circumstances. For example, consider the same page shown in Figure 2.4, this time captured before the page is actually finished loading.

This time, the title of the page is prepended with the word “Loading” and quotation marks, which were inserted by the Safari browser. When using intitle, be sure to consider what text is actually from the title and which text might have been inserted by the browser.

Title text is not limited, however, to the TITLE HTML tag. A Web page’s document can be generated in any number of ways, and in some cases, a Web page might not even have a title at all. The thing to remember is that the title is the text that appears at the top of the Web page, and you can use intitle to locate text in that spot.

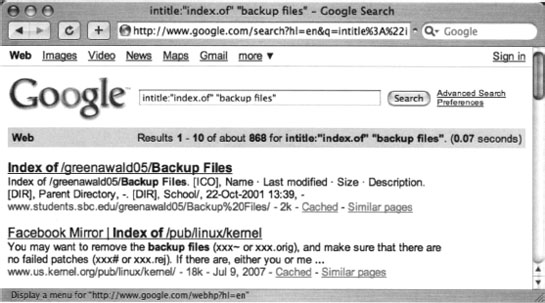

When using intitle, it’s important that you pay special attention to the syntax of the search string, since the word or phrase following the word intitle is considered the search phrase. Allintitle breaks this rule. Allintitle tells Google that every single word or phrase that follows is to be found in the title of the page. For example, we just looked at the intitle: “index of” “backup files” query as an example of an intitle search. In this query, the term “backup files” is found not in the title of the second hit but rather in the text of the document, as shown in Figure 2.5.

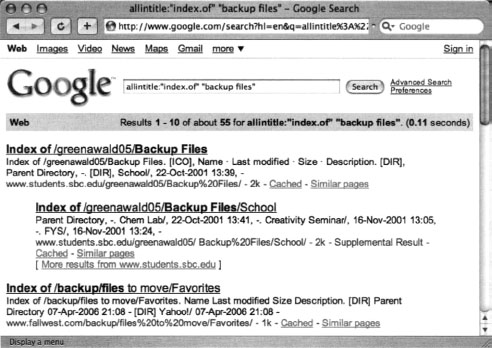

If we were to modify this query to allintitle: “index of” “backup files” we would get a different response from Google, as shown in Figure 2.6.

Now, every hit contains both “index of” and “backup files” in the title of each hit. Notice also that the allintitle search is also more restrictive, returning only a fraction of the results as the intitle search.

Google highlights search terms using multiple colors when you’re viewing the cached version of a page, and uses a bold typeface when displaying search terms on the search results pages. Don’t let this confuse you if the term is highlighted in a way that’s not consistent with your search syntax. Google highlights your search terms everywhere they appear in the search results. You can also use Google’s cache as a sort of virtual highlighter. Experiment with modifying a Google cache URL. Locate your search terms in the URL, and add words around your search terms. If you do it correctly and those words are present, Google will highlight those new words on the page.

Be wary of using the allintitle operator. It tends to be clumsy when it’s used with other advanced operators and tends to break the query entirely, causing it to return no results. It’s better to go overboard and use a bunch of intitle operators in a query than to screw it up with allintitle’s funky conventions.

Allintext: Locate a String Within the Text of a Page

The allintext operator is perhaps the simplest operator to use since it performs the function that search engines are most known for: locating a term within the text of the page. Although this advanced operator might seem too generic to be of any real use, it is handy when you know that the text you’re looking for should only be found in the text of the page. Using allintext can also serve as a type of shorthand for “find this string anywhere except in the title, the URL, and links.” Since this operator starts with the word all, every search term provided after the operator is considered part of the operator’s search query.

For this reason, the allintext operator should not be mixed with other advanced operators.

Inurl and Allinurl: Finding Text in a URL

Having been exposed to the intitle operators, it might seem like a fairly simple task to start throwing around the inurl operator with reckless abandon. I encourage such flights of searching fancy, but first realize that a URL is a much more complicated beast than a simple page title, and the workings of the inurl operator can be equally complex.

First, let’s talk about what a URL is. Short for Uniform Resource Locator, a URL is simply the address of a Web page. The beginning of a URL consists of a protocol, followed by://, like the very common http:// or ftp://. Following the protocol is an address followed by a pathname, all separated by forward slashes (/). Following the pathname comes an optional filename. A common basic URL, like http://www.uriah.com/apple-qt/1984.html, can be seen as several different components. The protocol, http, indicates that this is basically a Web server. The server is located at www.uriah.com, and the requested file, 1984.html, is found in the /apple-qt directory on the server. As we saw in the previous chapter, a Google search can be conveyed as a URL, which can look something like http://www.google.com/search?q=ihackstuff.

We’ve discussed the protocol, server, directory, and file pieces of the URL, but that last part of our example URL, ?q-ihackstuff, bears a bit more examination. Explained simply, this is a list of parameters that are being passed into the “search” program or file. Without going into much more detail, simply understand that all this “stuff” is considered to be part of the URL, which Google can be instructed to search with the inurl and allinurl operators.

So far this doesn’t seem much more complex than dealing with the intitle operator, but there are a few complications. First, Google can’t effectively search the protocol portion of the URL—http://, for example. Second, there are a ton of special characters sprinkled around the URL, which Google also has trouble weeding through. Attempting to specifically include these special characters in a search could cause unexpected results and might limit your search in undesired ways. Third, and most important, other advanced operators (site and filetype, for example) can search more specific places inside the URL even better than inurl can. These factors make inurl much trickier to use effectively than an intitle search, which is very simple by comparison. Regardless, inurl is one of the most indispensable operators for advanced Google users; we’ll see it used extensively throughout this book.

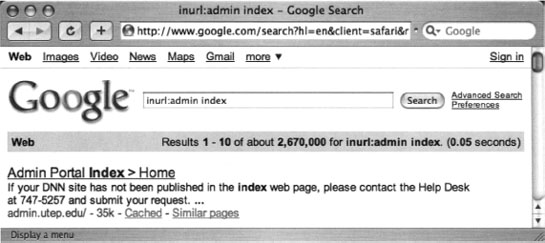

As with the intitle operator, inurl has a companion operator, known as allinurl. Consider the inurl search results page shown in Figure 2.7.

This search located the word admin in the URL of the document and the word index anywhere in the document, returning more than two million results. Replacing the intitle search with an allintitle search, we receive the results page shown in Figure 2.8.

This time, Google was instructed to find the words admin and index only in the URL of the document, resulting in about a million less hits. Just like the allintitle search, allinurl tells Google that every single word or phrase that follows is to be found only in the URL of the page. And just like allintitle, allinurl does not play very well with other queries. If you need to find several words or phrases in a URL, it’s better to supply several inurl queries than to succumb to the rather unfriendly allinurl conventions.

Site: Narrow Search to Specific Sites

Although technically a part of a URL, the address (or domain name) of a server can best be searched for with the site operator. Site allows you to search only for pages that are hosted on a specific server or in a specific domain. Although fairly straightforward, proper use of the site operator can take a little bit of getting used to, since Google reads Web server names from right to left, as opposed to the human convention of reading site names from left to right. Consider a common Web server name, www.apple.com. To locate pages that are hosted on blackhat.com, a simple query of site:blackhat.com will suffice, as shown in Figure 2.9.

Notice that the first two results are from www.blackhat.com andjapan.blackhat.com. Both of these servers end in blackhat.com and are valid results of our query.

Like many of Google’s advanced operators, site can be used in interesting ways. Take, for example, a query for site:r, the results of which are shown in Figure 2.10.

Look very closely at the results of the query and you’ll discover that the URL for the first returned result looks a bit odd. Truth be told, this result is odd. Google (and the Internet at large) reads server names (really domain names) from right to left, not from left to right. So a Google query for site:r can never return valid results because there is no .r domain name. So why does Google return results? It’s hard to be certain, but one thing’s for sure: these oddball searches and their associated responses are very interesting to advanced search engine users and fuel the fire for further exploration.

So, what about that link that Google returned to r&besk.tr.cx? What is that thing? I coined the term googleturd to describe what is most likely a typo that was crawled by Google. Depending on certain undisclosed circumstances, oddball links like these are sometimes retained. Googleturds can be useful, as we will see later on.

The site operator can be easily combined with other searches and operators, as we’ll see later in this chapter.

Filetype: Search for Files of a Specific Type

Google searches more than just Web pages. Google can search many different types of files, including PDF (Adobe Portable Document Format) and Microsoft Office documents. The filetype operator can help you search for these types of files. More specifically filetype searches for pages that end in a particular file extension. The file extension is the part of the URL following the last period of the filename but before the question mark that begins the parameter list. Since the file extension can indicate what type of program opens a file, the filetype operator can be used to search for specific types of files by searching for a specific file extension. Table 2.1 shows the main file types that Google searches, according to www.google.com/help/faq_filetypes.html#what.

Table 2.1 The Main File Types Google Searches

| File Type | File Extension |

|---|---|

| Adobe Portable Document Format | |

| Adobe PostScript | Ps |

| Lotus 1-2-3 | wk1, wk2, wk3, wk4, wk5, wki, wks, wku |

| Lotus WordPro | Lwp |

| MacWrite | Mw |

| Microsoft Excel | Xls |

| Microsoft PowerPoint | Ppt |

| Microsoft Word | Doc |

| Microsoft Works | wks, wps, wdb |

| Microsoft Write | Wri |

| Rich Text Format | Rtf |

| Shockwave Flash | Swf |

| Text | ans, txt |

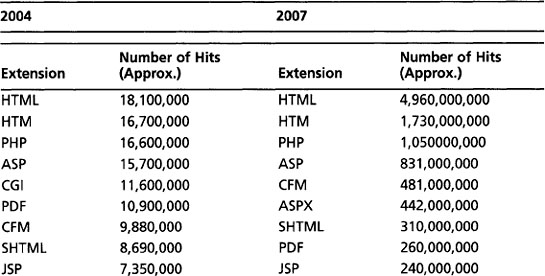

Table 2.1 does not list every file type that Google will attempt to search. According to http://filext.org, there are thousands of known file extensions. Google has examples of each and every one of these extensions in its database! This means that Google will crawl any type of page with any kind of extension, but understand that Google might not have the capability to search an unknown file type. Table 2.1 listed the main file types that Google searches, but you might be wondering which of the thousands of file extensions are the most prevalent on the Web. Table 2.2 lists the top 25 file extensions found on the Web, sorted by the number of hits for that file type.

The data in Table 2.2 came from two sources: filext.org and Google. First, I used lynx to scrape portions of the filext.org Web site in order to compile a list of known file extensions. For example, this line of bash will extract every file extension starting with the letter A, outputting it to a file called extensions:

lynx -source “http://filext.com/alphalist.php?extstart=%5EA” | grep “<td width="120"” | awk -F “file-extension/” `{print $2}’ | awk -F “"” `{print $1}’ > extensions

Then, each extension is fired through a Google filext search, to concentrate on the Results line:

for ext in $$cat extensions$$; do lynx -dump

“http://www.google.com/search?q=filetype:$ext” | grep Results | grep “of about”; done

The process took tens of thousands of queries and several hours to run. Google was gracious enough not to blacklist me for the flagrant violation of its Terms of Use!

So Much has changed in the three years since this process was run for the first edition. Just look at how many more hits Google is reporting! The jump in hits is staggering. If you’re unfamiliar with some of these extensions, check out www.filext.com, a great resource for getting detailed information about file extensions, what they are, and what programs they are associated with.

Google converts every document it searches to either HTML or text for online viewing. You can see that Google has searched and converted a file by looking at the results page shown in Figure 2.11.

Notice that the first result lists [DOC] before the title of the document and a file format of Microsoft Word. This indicates that Google recognized the file as a Microsoft Word document. In addition, Google has provided a View as HTML link that when clicked will display an HTML approximation of the file, as shown in Figure 2.12.

When you click the link for a document that Google has converted, a header is displayed at the top of the page, indicating that you are viewing the HTML version of the page. A link to the original file is also provided. If you think this looks similar to the cached view of a page, you’re right. This is the cached version of the original page, converted to HTML.

Although these are great features, Google isn’t perfect. Keep these things in mind:

Google doesn’t always provide a link to the converted version of a page.

Google doesn’t always provide a link to the converted version of a page. Google doesn’t always properly recognize the file type of even the most common file formats.

Google doesn’t always properly recognize the file type of even the most common file formats. When Google crawls a page that ends in a particular file extension but that file is blank, Google will sometimes provide a valid file type and a link to the converted page. Even the HTML version of a blank Word document is still, well, blank.

When Google crawls a page that ends in a particular file extension but that file is blank, Google will sometimes provide a valid file type and a link to the converted page. Even the HTML version of a blank Word document is still, well, blank.

This operator flakes out when ORed. As an example, the query filetype:doc returns 39 million results. The query filetype:pdf returns 255 million results. The query (filetype:doc | filetype:pdf) returns 335 million results, which is pretty close to the two individual search results combined. However, when you start adding to this precocious combination with things like (filetype:doc | filetpye:pdf) (doc | pdf), Google flakes out and returns 441 million results: even more than the original, broader query. I’ve found that Boolean logic applied to this operator is usually flaky, so beware when you start tinkering.

This operator can be mixed with other operators and search terms.

We simply can’t state this enough: The real hackers play in the gray areas all the time. The filetype operator opens up another interesting playground for the true Google hacker. Consider the query filetype:xls-xls. This query should return zero results, since XLS have XLS in the URL, right? Wrong. At the time of this writing, this query returns over 7,000 results, all of which are odd in their own right.

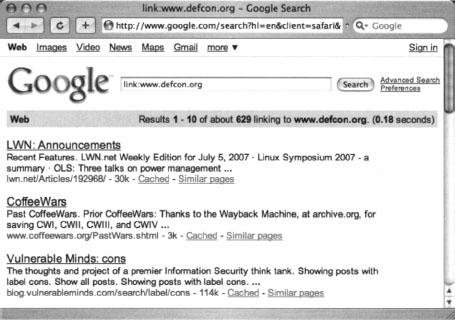

Link: Search for Links to a Page

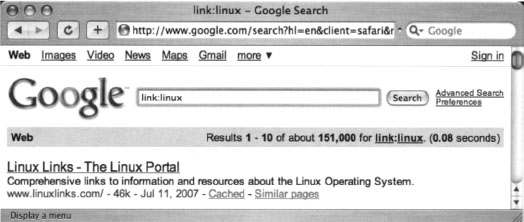

The link operator allows you to search for pages that link to other pages. Instead of providing a search term, the link operator requires a URL or server name as an argument. Shown in its most basic form, link is used with a server name, as shown in Figure 2.13.

Each of the search results shown in Figure 2.10 contains HTML links to the http://www.defcon.org Web site. The link operator can be extended to include not only basic URLs, but complete URLs that include directory names, filenames, parameters, and the like. Keep in mind that long URLs are much more specific and will return fewer results than their shorter counterparts.

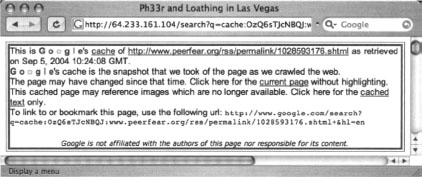

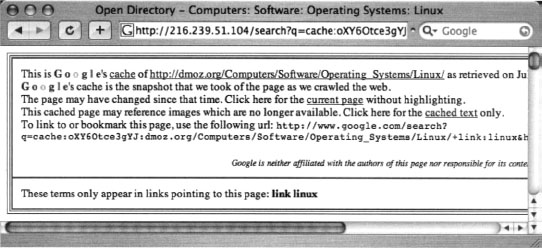

The only place the URL of a link is visible is in the browser’s status bar or in the source of the page. For that reason, unlike other cached pages, the cached page for a link operator’s search result does not highlight the search term, since the search term (the linked Web site) is never really shown in the page. In fact, the cached banner does not make any reference to your search query, as shown in Figure 2.14.

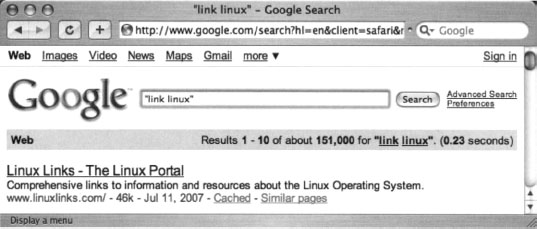

It is a common misconception to think that the link operator can actually search for text within a link. The inanchor operator performs something similar to this, as we’ll see next. To properly use the link operator, you must provide a full URL (including protocol, server, directory, and file), a partial URL (including only the protocol and the host), or simply a server name; otherwise, Google could return unpredictable results. As an example, consider a search for link:linux, which returns 151,000 results. This search is not the proper syntax for a link search, since the domain name is invalid. The correct syntax for a search like this might be link:linux.org (with 317 results) or link:linux.org (with no results).These numbers don’t seem to make sense, and they certainly don’t begin to account for the 151,000 hits on the original query. So what exactly is being returned from Google for a search like link:linux? Figures 2.15 and 2.16 show the answer to this question.

When an invalid link: syntax is provided, Google treats the search as a phrase search. Google offers another clue as to how it handles invalid link searches through the cache page. As shown in Figure 2.17, the cached banner for a site found with a link:linux search does not resemble a typical link search cached banner, but rather a standard search cache banner with included highlighted terms.

This is an indication that Google did not perform a link search, but instead treated the search as a phrase, with a colon representing a word break.

The link operator cannot be used with other operators or search terms.

Inanchor: Locate Text Within Link Text

This operator can be considered a companion to the link operator, since they both help search links. The inanchor operator, however, searches the text representation of a link, not the actual URL. For example, in Figure 2.17, the Google link to “current page” is shown in typical form—as an underlined portion of text. When you click that link, you are taken to the URL http://dmoz.org/Computers/Software/Operating_Systems/Linux. If you were to look at the actual source of that page, you would see something like this:

<A HREF="http:// dmoz.org/ Computers/ Software/ Operating_Systems/ Linux/ ">current page</A>

The inanchor operator helps search the anchor, or the displayed text on the link, which in this case is the phrase “current page”. This is not the same as using inurl to find this page with a query like inurl:Computers inurl:Operating_Systems.

Inanchor accepts a word or phrase as an argument, such as inanchor:click or inanchor:James.Foster. This search will be handy later, especially when we begin to explore ways of searching for relationships between sites. The inanchor operator can be used with other operators and search terms.

Cache: Show the Cached Version of a Page

As we’ve already discussed, Google keeps snapshots of pages it has crawled that we can access via the cached link on the search results page. If you would like to jump right to the cached version of a page without first performing a Google query to get to the cached link on the results page, you can simply use the cache advanced operator in a Google query such as cache:blackhat.com or cache:www.netsec.net/content/index.jsp. If you don’t supply a complete URL or hostname, Google could return unpredictable results. Just as with the link operator, passing an invalid hostname or URL as a parameter to cache will submit the query as a phrase search. A search for cache:linux returns exactly as many results as “cache linux”, indicating that Google did indeed treat the cache search as a standard phrase search.

The cache operator can be used with other operators and terms, although the results are somewhat unpredictable.

Numrange: Search for a Number

The numrange operator requires two parameters, a low number and a high number, separated by a dash. This operator is powerful but dangerous when used by malicious Google hackers. As the name suggests, numrange can be used to find numbers within a range. For example, to locate the number 12345, a query such as numrange: 12344–12346 will work just fine. When searching for numbers, Google ignores symbols such as currency markers and commas, making it much easier to search for numbers on a page. A shortened version of this operator exists as well. Instead of supplying the numrange operator, you can simply provide two numbers in a query, separated by two periods. The shortened version of the query just mentioned would be 12344..12346. Notice that the numrange operator was left out of the query entirely.

This operator can be used with other operators and search terms.

If Gandalf the Grey were to author this sidebar, he wouldn’t be able to resist saying something like “There are fouler things than characters lurking in the dark places of Google’s cache.” The most grave examples of Google’s power lies in the use of the numrange operator. It would be extremely irresponsible of me to share these powerful queries with you. Fortunately, the abuse of this operator has been curbed due to the diligence of the hard-working members of the Search Engine Hacking forums at http://johnny.ihackstuff.com. The members of that community have taken the high road time and time again to get the word out about the dangers of Google hackers without spilling the beans and creating even more hackers. This sidebar is dedicated to them!

Daterange: Search for Pages Published Within a Certain Date Range

The daterange operator can tend to be a bit clumsy, but it is certainly helpful and worth the effort to understand. You can use this operator to locate pages indexed by Google within a certain date range. Every time Google crawls a page, this date changes. If Google locates some very obscure Web page, it might only crawl it once, never returning to index it again. If you find that your searches are clogged with these types of obscure Web pages, you can remove them from your search (and subsequently get fresher results) through effective use of the daterange operator.

The parameters to this operator must always be expressed as a range, two dates separated by a dash. If you only want to locate pages that were indexed on one specific date, you must provide the same date twice, separated by a dash. If this sounds too easy to be true, you’re right. It is too easy to be true. Both dates passed to this operator must be in the form of two Julian dates. The Julian date is the number of days that have passed since January 1, 4713 B.C. For example, the date September 11, 2001, is represented in Julian terms as 2452164. So, to search for pages that were indexed by Google on September 11, 2001, and contained the word “osama bin laden,” the query would be daterange:2452164–2452164 “osama bin laden”.

Google does not officially support the daterange operator, and as such your mileage may vary. Google seems to prefer the date limit used by the advanced search form at www.google.com/advanced_search. As we discussed in the last chapter, this form creates fields in the URL string to perform specific functions. Google designed the as_qdr field to help you locate pages that have been updated within a certain time frame. For example, to find pages that have been updated within the past three months and that contain the word Google, use the query http://www.google.com/search?q=google&as_qdr=m3.

This might be a better alternative date restrictor than the clumsy daterange operator. Just understand that these are very different functions. Daterange is not the advanced-operator equivalent for as_qdr, and unfortunately, there is no operator equivalent. If you want to find pages that have been updated within the past year or less, you must either use Google advanced search interface or stick &as_qdr=3m (or equivalent) on the end of your URL.

The daterange operator must be used with other search terms or advanced operators. It will not return any results when used by itself.

Info: Show Google’s Summary Information

The info operator shows the summary information for a site and provides links to other Google searches that might pertain to that site, as shown in Figure 2.18. The parameter to this operator must be a valid URL or site name. You can achieve this same functionality by supplying a site name or URL as a search query.

If you don’t supply a complete URL or hostname, Google could return unpredictable results. Just as with the link and cache operators, passing an invalid hostname or URL as a parameter to info will submit the query as a phrase search. A search for info:linux returns exactly as many results as “info linux”, indicating that Google did indeed treat the info search as a standard phrase search.

The info operator cannot be used with other operators or search terms.

Related: Show Related Sites

The related operator displays sites that Google has determined are related to a site, as shown in Figure 2.19. The parameter to this operator is a valid site name or URL. You can achieve this same functionality by clicking the “Similar Pages” link from any search results page, or by using the “Find pages similar to the page” portion of the advanced search form (shown in Figure 2.19).

If you don’t supply a complete URL or hostname, Google could return unpredictable results. Passing an invalid hostname or URL as a parameter to related will submit the query as a phrase search. A search for related:linux returns exactly as many results as “related linux”, indicating that Google did indeed treat the cache search as a standard phrase search.

The related operator cannot be used with other operators or search terms.

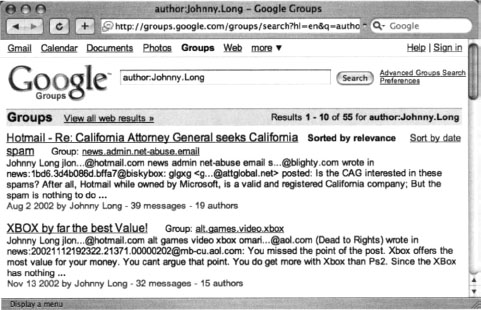

Author: Search Groups for an Author of a Newsgroup Post

The author operator will allow you to search for the author of a newsgroup post. The parameter to this option consists of a name or an e-mail address. This operator can only be used in conjunction with a Google Groups search. Attempting to use this operator outside a Groups search will result in an error. When you’re searching for a simple name, such as author-Johnny, the search results will include posts written by anyone with the first, middle, or last name of Johnny, as shown in Figure 2.20.

As you can see, we’ve got hits for Johnny Lurker, Johnny Walker, Johnny, and Johnny Anderson. Makes you wonder if those are real names, doesn’t it? In most cases, these are not real names. This is the nature of the newsgroup beast. Pseudo-anonymity is fairly easy to maintain when anyone can post to newsgroups through Google using nothing more than a free e-mail account as verification.

The author operator can be a bit clumsy to use, since it doesn’t interpret its parameters in exactly the same way as some of the operators. Simple searches such as author:Johnny or author:[email protected] work just as expected, but things get dicey when we attempt to search for names given in the form of a phrase. Consider a search like author:“Johnny Long”, an attempt to search for an author with a full name of Johnny Long. This search fails pretty miserably, as shown in Figure 2.21.

Passing the query of author:Johnny.long, however, gets us the results we’re expecting: Johnny Long as the posts’ author, as shown in Figure 2.22.

The author operator can be used with other valid Groups operators or search terms.

Group: Search Group Titles

This operator allows you to search the title of Google Groups posts for search terms. This operator only works within Google Groups. This is one of the operators that is very compatible with wildcards. For example, to search for groups that end in forsale, a search such as group:*.forsale works very well. In some cases, Google finds your search term not in the actual name of the group but in the keywords describing the group. Consider the search group:windows, as shown in Figure 2.23. Not all of the groups returned contain the word windows, but all the returned groups discuss Windows topics.

In our experience, the group operator does not mix very well with other operators. If you get odd results when throwing group into the mix, try using other operators such as intitle to compensate.

Insubject: Search Google Groups Subject Lines

The insubject operator is effectively the same as the intitle search and returns the same results. Searches for intitle:dragon and insubject:dragon return exactly the same number of results. This is most likely because the subject of a group post is also the title of the post. Subject is (and was, in USENET) the more precise term for a message title, and this operator most likely exists to help ease the mental shift from “deja/USENET searching” to Google searching.

Just like the intitle operator, insubject can be used with other operators and search terms.

Msgid: Locate a Group Post by Message ID

In the first edition of this book, I presented the msgid operator, which displays one specific message in Google Groups. This operator took only one argument, a group message identifier. A message identifier (or message ID) is a unique string that identifies a newsgroup post. The format is something like [email protected]. Things have changed since that printing, and now msgid is mostly broken, replaced by the as_msgid search URL parameter, now accessible through the advanced groups page at http://groups.google.com/advanced_search. However, we’ll discuss Message IDs here to give you an idea of how that functionality worked, just in case the msgid parameter is brought back to life.

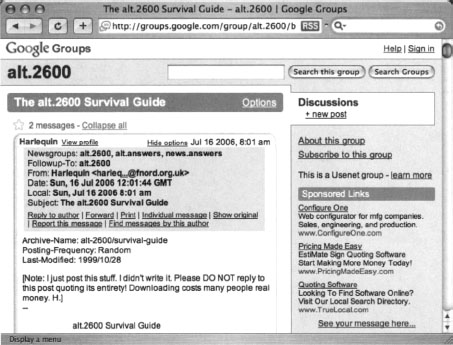

To view message IDs, you must view the original group post format. When viewing a post (see Figure 2.24), simply click Show Options and then follow the Show original link. You will be taken to a page that lists the entire content of the group post, as shown in Figure 2.25.

The Message ID of this message ([email protected]) can be used in the advance search form, with the as_msgid URL parameter, or with the msgid operator should it make a comeback.

When operational, the msgid operator does not mix with other operators or search terms.

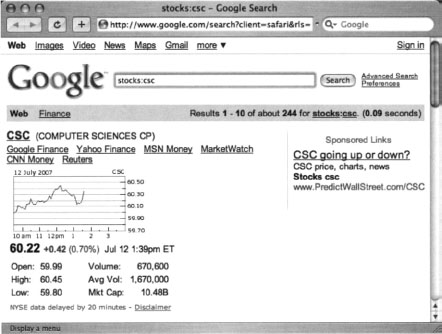

Stocks: Search for Stock Information

The stocks operator allows you to search for stock market information about a particular company. The parameter to this operator must be a valid stock abbreviation. If you provide an valid stock ticker symbol, you will be taken to a screen that allows further searching for a correct ticker symbol, as shown in Figure 2.26.

The stocks operator cannot be used with other operators or search terms.

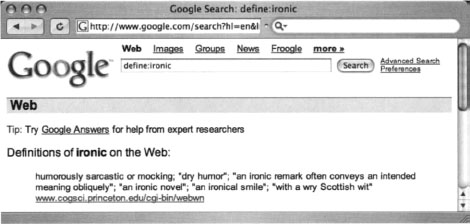

Define: Show the Definition of a Term

The define operator returns definitions for a search term. Fairly simple, and very straightforward, arguments to this operator may be a word or phrase. Links to the source of the definition are provided, as shown in Figure 2.27.

The define operator cannot be used with other operators or search terms.

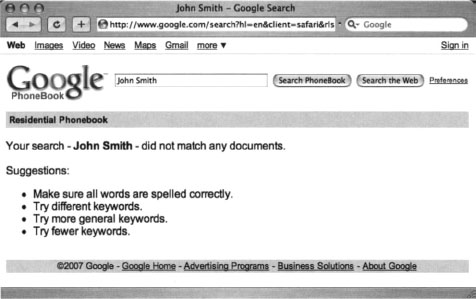

Phonebook: Search Phone Listings

The phonebook operator searches for business and residential phone listings. Three operators can be used for the phonebook search: rphonebook, bphonebook, and phonebook, which will search residential listings, business listings, or both, respectively. The parameters to these operators are all the same and usually consist of a series of words describing the listing and location. In many ways, this operator functions like an allintitle search, since every word listed after the operator is included in the operator search. A query such as phonebook:john darling ny would list both business and residential listings for John Darling in New York. As shown in Figure 2.28, links are provided for popular mapping sites that allow you to view maps of an address or location.

To get access to business listings, play around with the bphonebook operator. This operator doesn’t always work as expected, but for certain queries (like bphonebook:korean food Washington DC, shown below in Figure 2.29) it works very well, transporting you to a Google Local listing of businesses that match the description.

There are other ways to get to this information without the phonebook operators. If you supply what looks like an address (including a state) or a name and a state as a standard query, Google will return a link allowing you to map the location in the case of an address or a phone listing in the case of a name and street match.

If you’re concerned about your address information being in Google’s databases for the world to see, have no fear. Google makes it possible for you to delete your information so others can’t access it via Google. Simply fill out the form at www.google.com/help/pbremoval.html and your information will be removed, usually within 48 hours. This doesn’t remove you from the Internet (let us know if you find a link to do that), but the page gives you a decent list of places that list similar information. Oh, and Google is trusting you not to delete other people’s information with this form.

The phonebook operators do not provide very informative error messages, and it can be fairly difficult to figure out whether or not you have bad syntax. Consider a query for phonebook:john smith. This query does not return any results, and the results page looks a lot like a standard “no results” page, as shown in Figure 2.30.

To make matters worse, the suggestions for fixing this query are all wrong. In this case, you need to provide more information in your query to get hits, not fewer keywords, as Google suggests. Consider phonebook:john smith ny, which returns approximately 600 results.

Colliding Operators and Bad Search-Fu

As you start using advanced operators, you’ll realize that some combinations work better than others for finding what you’re looking for. Just as quickly, you’ll begin to realize that some operators just don’t mix well at all. Table 2.3 shows which operators can be mixed with others. Operators listed as “No” should not be used in the same query as other operators. Furthermore, these operators will sometimes give funky results if you get too fancy with their syntax, so don’t be surprised when it happens.

This table also lists operators that can only be used within specific Google search areas and operators that cannot be used alone. The values in this table bear some explanation. A box marked “Yes” indicates that the operator works as expected in that context. A box marked “No” indicates that the operator does not work in that context, and Google indicates this with a warning message. Any box marked with “Not really” indicates that Google attempts to translate your query when used in that context. True Google hackers love exploring gray areas like the ones found in the “Not really” boxes.

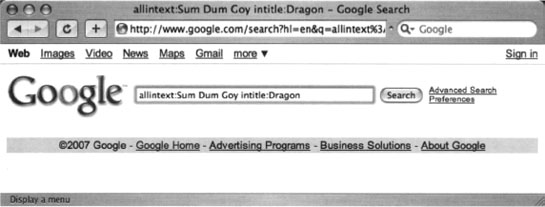

Allintext gives all sorts of crazy results when it is mixed with other operators. For example, a search for allintext:moo goo gai filetype:pdf works well for finding Chinese food menus, whereas allintext:Sum Dum Goy intitle:Dragon gives you that empty feeling inside—like a year without the 1985 classic The Last Dragon (see Figure 2.31).

Despite the fact that some operators do combine with others, it’s still possible to get less than optimal results by running your operators head-on into each other. This section focuses on pointing out a few of the potential bad collisions that could cause you headaches. We’ll start with some of the more obvious ones.

First, consider a query like something—something. By asking for something and taking away something, we end up with… nothing, and Google tells you as much. This is an obvious example, but consider intitle:something—intitle:something. This query, just like the first, returns nothing, since we’ve negated our first search with a duplicate NOT search. Literally, we’re saying “find something in the title and hide all the results with something in the title.” Both of these examples clearly illustrate the point that you can’t query for something and negate that query, because your results will be zero.

It gets a bit tricky when the advanced operators start overlapping. Consider site and inurl. The URL includes the name of the site. So, extending the “don’t contradict yourself” rule, don’t include a term with site and exclude that term with inurl and vice versa and expect sane results. A query like site:microsoft.com -inurl:microsoft.com doesn’t make much sense at all, and shouldn’t work, but as Figure 2.32 shows, it does work.

When you’re really trying to home in on a topic, keep the “rules” in mind and you’ll accelerate toward your target at a much faster pace. Save the rule breaking for your required Google hacking license test!

Here’s a quick breakdown of some broken searches and why they’re broken:

Summary

Google offers plenty of options when it comes to performing advanced searches. URL modification, discussed in Chapter 1, can provide you with lots of options for modifying a previously submitted search, but advanced operators are better used within a query. Easier to remember than the URL modifiers, advance operators are the truest tools of any Google hacker’s arsenal. As such, they should be the tools used by the good guys when considering the protection of Web-based information.

Most of the operators can be used in combination, the most notable exceptions being the allintitle, allinurl, allinanchor, and allintext operators. Advanced Google searchers tend to steer away from these operators, opting to use the intitle, inurl, and link operators to find strings within the title, URL, or links to pages, respectively. Allintext, used to locate all the supplied search terms within the text of a document, is one of the least used and most redundant of the advanced operators. Filetype and site are very powerful operators that search specific sites or specific file types. The daterange operator allows you to search for files that were indexed within a certain time frame, although the URL parameter as_qdr seems to be more in vogue. When crawling Web pages, Google generates specific information such as a cached copy of a page, an information snippet about the page, and a list of sites that seem related. This information can be retrieved with the cache, info, and related operators, respectively. To search for the author of a Google Groups document, use the author operator. The phonebook series of operators return business or residential phone listings as well as maps to specific addresses. The stocks operator returns stock information about a specific ticker symbol, whereas the define operator returns the definition of a word or simple phrase.

Solutions Fast Track

Intitle

Finds strings in the title of a page

Finds strings in the title of a page Mixes well with other operators

Mixes well with other operators Best used with Web, Group, Images, and News searches

Best used with Web, Group, Images, and News searches

Allintitle

Finds all terms in the title of a page

Finds all terms in the title of a page Does not mix well with other operators or search terms

Does not mix well with other operators or search terms Best used with Web, Group, Images, and News searches

Best used with Web, Group, Images, and News searches

Inurl

Finds strings in the URL of a page

Finds strings in the URL of a page Mixes well with other operators

Mixes well with other operators Best used with Web and Image searches

Best used with Web and Image searches

Allinurl

Finds all terms in the URL of a page

Finds all terms in the URL of a page Does not mix well with other operators or search terms

Does not mix well with other operators or search terms Best used with Web, Group, and Image searches

Best used with Web, Group, and Image searches

Filetype

Finds specific types of files based on file extension

Finds specific types of files based on file extension Synonymous with ext

Synonymous with ext Requires an additional search term

Requires an additional search term Mixes well with other operators

Mixes well with other operators Best used with Web and Group searches

Best used with Web and Group searches

Allintext

Finds all provided terms in the text of a page

Finds all provided terms in the text of a page Pure evil—don’t use it

Pure evil—don’t use it Forget you ever heard about allintext

Forget you ever heard about allintext

Site

Restricts a search to a particular site or domain

Restricts a search to a particular site or domain Mixes well with other operators

Mixes well with other operators Can be used alone

Can be used alone Best used with Web, Groups and Image searches

Best used with Web, Groups and Image searches

Link

Searches for links to a site or URL

Searches for links to a site or URL Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches

Inanchor

Finds text in the descriptive text of links

Finds text in the descriptive text of links Mixes well with other operators and search terms

Mixes well with other operators and search terms Best used for Web, Image, and News searches

Best used for Web, Image, and News searches

Daterange

Locates pages indexed within a specific date range

Locates pages indexed within a specific date range Requires a search term

Requires a search term Mixes well with other operators and search terms

Mixes well with other operators and search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches Might be phased out to make way for as_qdr.

Might be phased out to make way for as_qdr.

Nurnrange

Finds a number in a particular range

Finds a number in a particular range Mixes well with other operators and search terms

Mixes well with other operators and search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches Synonymous with ext.

Synonymous with ext.

Cache

Displays Google’s cached copy of a page

Displays Google’s cached copy of a page Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches

Info

Displays summary information about a page

Displays summary information about a page Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches

Related

Shows sites that are related to provided site or URL

Shows sites that are related to provided site or URL Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used with Web searches

Best used with Web searches

Phonebook, Rphonebook, / Bphonebook

Shows residential or business phone listings

Shows residential or business phone listings Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used as a Web query

Best used as a Web query

Author

Searches for the author of a Group post

Searches for the author of a Group post Mixes well with other operators and search terms

Mixes well with other operators and search terms Best used as a Group search

Best used as a Group search

Group

Searches Group names, selects individual Groups

Searches Group names, selects individual Groups Mixes well with other operators

Mixes well with other operators Best used as a Group search

Best used as a Group search

Insubject

Locates a string in the subject of a Group post

Locates a string in the subject of a Group post Mixes well with other operators and search terms

Mixes well with other operators and search terms Best used as a Group search

Best used as a Group search

Msgid

Locates a Group message by message ID

Locates a Group message by message ID Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best used as a Group search

Best used as a Group search Flaky Use the advanced search form at groups.google.com/advanced_search instead

Flaky Use the advanced search form at groups.google.com/advanced_search instead

Stocks

Shows the Yahoo Finance stock listing for a ticker symbol

Shows the Yahoo Finance stock listing for a ticker symbol Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best provided as a Web query

Best provided as a Web query

Define

Shows various definitions of a provided word or phrase

Shows various definitions of a provided word or phrase Does not mix with other operators or search terms

Does not mix with other operators or search terms Best provided as a Web query

Best provided as a Web query

Links to Sites

The Google filetypes FAQ, www.google.com/help/faq_filetypes.html

The Google filetypes FAQ, www.google.com/help/faq_filetypes.html The resource for file extension information, www.filext.com This site can help you figure out what program a particular extension is associated with.

The resource for file extension information, www.filext.com This site can help you figure out what program a particular extension is associated with. http://searchenginewatch.com/searchday/article.php/2160061?? This article discusses some of the issues associated with Google’s date restrict search options.

http://searchenginewatch.com/searchday/article.php/2160061?? This article discusses some of the issues associated with Google’s date restrict search options. Very nice online Julian date converters, www.24hourtranslations.co.uk/dates.htm and www.tesre.bo.cnr.it/∼mauro/JD/

Very nice online Julian date converters, www.24hourtranslations.co.uk/dates.htm and www.tesre.bo.cnr.it/∼mauro/JD/

Frequently Asked Questions

The following Frequently Asked Questions, answered by the authors of this book, are designed to both measure your understanding of the concepts presented in this chapter and to assist you with real-life implementation of these concepts. To have your questions about this chapter answered by the author, browse to www.syngress.com/solutions and click on the “Ask the Author” form.

AltaVista offers domain, host, link, title, and url operators. The AltaVista advanced search page can be found at www.altavista.com/web/adv. Of particular interest is the timeframe search, which allows more granularity than Google’s as_qdr URL modifier, allowing you to search either ranges or specific time frames such as the past week, two weeks, or longer.