Chapter 4Document Grinding and Database Digging

Solutions in this chapter:

Configuration Files

Configuration Files Log Files

Log Files Office Documents

Office Documents Database Information

Database Information Automated Grinding

Automated Grinding Google Desktop

Google Desktop Links to Sites

Links to Sites

Introduction

There’s no shortage of documents on the Internet. Good guys and bad guys alike can use information found in documents to achieve their distinct purposes. In this chapter we take a look at ways you can use Google to not only locate these documents but to search within these documents to locate information. There are so many different types of documents and we can’t cover them all, but we’ll look at the documents in distinct categories based on their function. Specifically, we’ll take a look at configuration files, log files, and office documents. Once we’ve looked at distinct file types, we’ll delve into the realm of database digging. We won’t examine the details of the Structured Query Language (SQL) or database architecture and interaction; rather, we’ll look at the many ways Google hackers can locate and abuse database systems armed with nothing more than a search engine.

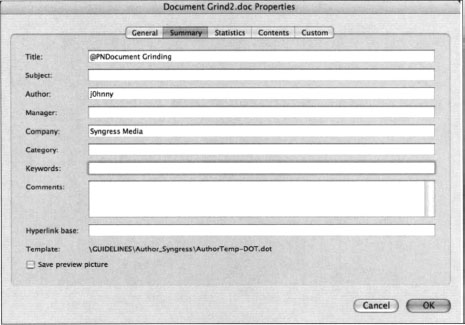

One important thing to remember about document digging is that Google will only search the rendered, or visible, view of a document. For example, consider a Microsoft Word document. This type of document can contain metadata, as shown in Figure 4.1. These fields include such things as the subject, author, manager, company, and much more. Google will not search these fields. If you’re interested in getting to the metadata within a file, you’ll have to download the actual file and check the metadata yourself, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Configuration Files

Configuration files store program settings. An attacker (or “security specialist”) can use these files to glean insight into the way a program is used and perhaps, by extension, into how the system or network it’s on is used or configured. As we’ve seen in previous chapters, even the smallest tidbit of information can be of interest to a skilled attacker.

Consider the file shown in Figure 4.2. This file, found with a query such as filetype:ini inurl:ws_ftp, is a configuration file used by the WS_FTP client program. When the WS_FTP program is downloaded and installed, the configuration file contains nothing more than a list of popular, public Internet FTP servers. However, over time, this configuration file can be automatically updated to include the name, directory, username, and password of FTP servers the user connects to. Although the password is encoded when it is stored, some free programs can crack these passwords with relative ease.

To locate files, it’s best to try different types of queries. For example, intitle:index.of ws_ftp.ini will return results, but so will filetype:ini inurl:ws_ftp.ini. The inurl search, however, is often the better choice. First, the filetype search allows you to browse right to a cached version of the page. Second, the directory listings found by the index.of search might allow you to view a list of files but not allow you access to the actual file. Third, directory listings are not overly common. The filetype search will locate your file no matter how Google found it.

Regardless of the type of data in a configuration file, sometimes the mere existence of a configuration file is significant. If a configuration file is located on a server, there’s a chance that the accompanying program is installed somewhere on that server or on neighboring machines on the network. Although this might not seem like a big deal in the case of FTP client software, consider a search like filetype:conf inurl:firewall, which can locate generic firewall configuration files. This example demonstrates one of the most generic naming conventions for a configuration file, the use of the conf file extension. Other generic naming conventions can be combined to locate other equally common naming conventions. One of the most common base searches for locating configuration files is simply (inurl:conf OR inurl:config OR inurl:cfg), which incorporates the three most common configuration file prefixes. You may also opt to use the filetype operator.

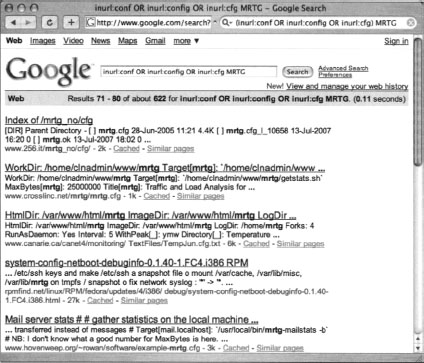

If an attacker knows the name of a configuration file as it shipped from the software author or vendor, he can simply create a search targeting that filename using the filetype and inurl operators. However, most programs allow you to reference a configuration file of any name, making a Google search slightly more difficult. In these cases, it helps to get an idea of the contents of the configuration file, which could be used to extract unique strings for use in an effective base search. Sometimes, combining a generic base search with the name (or acronym) of a software product can have satisfactory results, as a search for (inurl:conf OR inurl:config OR inurl:cfg) MRTG shows in Figure 4.3.

Although this first search is not far off the mark, it’s fairly common for even the best config file search to return page after page of sample or example files, like the sample MRTG configuration file shown in Figure 4.4.

This brings us back, once again, to perhaps the most valuable weapon in a Google hacker’s arsenal: effective search reduction. Here’s a list of the most common points a Google hacker considers when trolling for configuration files:

Create a strong base search using unique words or phrases from live files.

Create a strong base search using unique words or phrases from live files. Filter out the words sample, example, test, howto, and tutorial to narrow the obvious example files.

Filter out the words sample, example, test, howto, and tutorial to narrow the obvious example files. Filter out CVS repositories, which often house default config files, with —cvs.

Filter out CVS repositories, which often house default config files, with —cvs. Filter out manpage or Manual if you’re searching for a UNIX program’s configuration file.

Filter out manpage or Manual if you’re searching for a UNIX program’s configuration file. Locate the one most commonly changed field in a sample configuration file and perform a negative search on that field, reducing potentially “lame” or sample files.

Locate the one most commonly changed field in a sample configuration file and perform a negative search on that field, reducing potentially “lame” or sample files.

To illustrate these points, consider the search filetype:cfg mrtg “target[*]” -sample -cvs -example, which locates potentially live MRTG files. As shown in Figure 4.5, this query uses a unique string “target[*]” (which is a bit ubiquitous to Google, but still a decent place to start) and removes potential example and CVS files, returning decent results.

Some of the results shown in Figure 4.5 might not be real, live MRTG configuration files, but they all have potential, with the exception of the first hit, located in “/Squid-Book.” There’s a good chance that this is a sample file, but because of the reduction techniques we’ve used, the other results are potentially live, production MRTG configuration files.

Table 4.1 lists a collection of searches that locate various configuration files. These entries were gathered by the many contributors to the GHDB. This list highlights the various methods that can be used to target configuration files. You’ll see examples of CVS reduction, sample reduction, unique word and phrase isolation, and more. Most of these queries took imagination on the part of the creator and in many cases took several rounds of reduction by several searchers to get to the query you see here. Learn from these queries, and try them out for yourself. It might be helpful to remove some of the qualifiers, such as —cvs or -sample, where applicable, to get an idea of what the “messy” version of the search might look like.

Table 4.1 Configuration File Search Examples

Log Files

Log files record information. Depending on the application, the information recorded in a log file can include anything from timestamps and IP addresses to usernames and passwords—even incredibly sensitive data such as credit card numbers!

Like configuration files, log files often have a default name that can be used as part of a base search. The most common file extension for a log file is simply log, making the simplest base search for log files simply filetype:log inurl:log or the even simpler ext:log log. Remember that the ext (filetype) operator requires at least one search argument. Log file searches seem to return fewer samples and example files than configuration file searches, but search reduction is still required in some cases. Refer to the rules for configuration file reduction listed previously.

Table 4.2 lists a collection of log file searches collected from the GHDB. These searches show the various techniques that are employed by Google hackers and serve as an excellent learning tool for constructing your own searches during a penetration test.

Table 4.2 Log File Search Examples

| Query | Description |

|---|---|

| “ZoneAlarm Logging Client” | ZoneAlarm log files |

| “admin account info” filetype:log | Admin logs |

| “apricot - admin” 00h | Apricot logs |

| “by Reimar Hoven. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer” | inurl: “log/logdb.dta” | PHP Web Statistik logs |

| “generated by wwwstat” | www statistics |

| “Index of” / “chat/logs” | Chat logs |

| “MacHTTP” filetype:log inurl:machttp.log | MacHTTP |

| “Most Submitted Forms and Scripts” “this section” | www statistics |

| “sets mode: +k” | IRC logs, channel key set |

| “sets mode: +p” | IRC chat logs |

| “sets mode: +s” | IRC logs, secret channel set |

| “The statistics were last updated” “Daily"-microsoft.com | Network activity logs |

| “This report was generated by WebLog” | weblog-generated statistics |

| “your password is” filetype:log | Password logs |

| QueryProgram “ZoneAlarm Logging Client” | ZoneAlarm log files |

| +htpasswd WS_FTP.LOG filetype:log | WS_FTP client log files |

| +intext:“webalizer” +intext: “Total Usernames” +intext:“Usage Statistics for” | Webalizer statistics |

| ext:log “Software: Microsoft Internet Information Services *.*” | IIS server log files |

| ext:log password END_FILE | Java password files |

| filetype:cfg login “LoginServer=” | Ultima Online log files |

| filetype:log “PHP Parse error” | “PHP Warning” |” | PHP error logs |

| filetype:log “See `ipsec —copyright” | BARF log files |

| filetype:log access.log -CVS | HTTPD server access logs |

| filetype:log cron.log | UNIX cron logs |

| filetype:log hijackthis “scan saved” | Hijackthis scan log |

| filetype:log inurl:“password.log” | Password logs |

| filetype:log inurl:access.log TCP_HIT | Squid access log |

| filetype:log inurl:cache.log | Squid cache log |

| filetype:log inurl:store.log RELEASE | Squid disk store log |

| filetype:log inurl:useragent.log | Squid useragent log |

| filetype:log iserror.log | MS Install Shield logs |

| filetype:log iserror.log | MS Install Shield logs |

| filetype:log iserror.log | MS Install Shield logs |

| filetype:log username putty | Putty SSH client logs |

| filetype:log username putty | Putty SSH client logs |

| intext:“Session Start * * * *:*:* *” filetype:log | IRC/AIM log files |

| intitle:“HostMonitor log” | intitle: “HostMonitor report” | HostMonitor |

| intitle:“Index Of” -inurl:maillog maillog size | Mail log files |

| intitle:“LOGREP - Log file reporting system” -site:itefix.no | Logrep |

| intitle:index.of .bash_history | UNIX bash shell history file |

| intitle:index.of .sh_history | UNIX shell history file |

| intitle:index.of cleanup.log | Outlook Express cleanup logs |

| inurl:access.log filetype:log -cvs | Apache access log (Windows) |

| inurl:error.log filetype:log -cvs | Apache error log |

| inurl:log.nsf-gov | Lotus Domino |

| log inurl:linklint filetype:txt -"checking” | Linklint logs |

| Squid cache server reports | squid server cache reports |

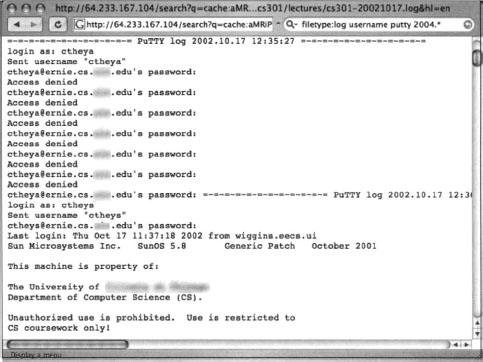

Log files reveal various types of information, as shown in the search for filetype: tog user-name putty in Figure 4.6. This log file lists machine names and associated usernames that could be reused in an attack against the machine.

Office Documents

The term office document generally refers to documents created by word processing software, spreadsheet software, and lightweight database programs. Common word processing software includes Microsoft Word, Corel WordPerfect, MacWrite, and Adobe Acrobat. Common spreadsheet programs include Microsoft Excel, Lotus 1-2-3, and Linux’s Gnumeric. Other documents that are generally lumped together under the office document category include Microsoft PowerPoint, Microsoft Works, and Microsoft Access documents. Table 4.3 lists some of the more common office document file types, organized roughly by their Internet popularity (based on number of Google hits).

Table 4.3 Popular Office Document File Types

| File Type | Extension |

|---|---|

| Adobe Portable Document Format | |

| Adobe PostScript | Ps |

| Lotus 1-2-3 | wk1, wk2, wk3, wk4, wk5, wki, wks, wku |

| Lotus WordPro | Lwp |

| MacWrite | Mw |

| Microsoft Excel | Xls |

| Microsoft PowerPoint | Ppt |

| Microsoft Word | Doc |

| Microsoft Works | wks, wps, wdb |

| Microsoft Write | Wri |

| Rich Text Format | Rtf |

| Shockwave Flash | Swf |

| Text | ans, txt |

In many cases, simply searching for these files with filetype is pointless without an additional specific search. Google hackers have successfully uncovered all sorts of interesting files by simply throwing search terms such as private or password or admin onto the tail end of a filetype search. However, simple base searches such as (inurl:xls OR inurl.doc OR inurl:mdb) can be used as a broad search across many file types.

Table 4.4 lists some searches from the GHDB that specifically target office documents. This list shows quite a few specific techniques that we can learn from. Some searches, such as filetype:xls inurl:password.xls, focus on a file with a specific name. The password.xls file does not necessarily belong to any specific software package, but it sounds interesting simply because of the name. Other searches, such as filetype:xls username password email, shift the focus from the file’s name to its contents. The reasoning here is that if an Excel spreadsheet contains the words username password and e-mail, there’s a good chance the spreadsheet contains sensitive data such as passwords. The heart and soul of a good Google search involves refining a generic search to uncover something extremely relevant. Google’s ability to search inside different types of documents is an extremely powerful tool in the hands of an advanced Google user.

Table 4.4 Sample Queries That Locate Potentially Sensitive Office Documents

| Query | Potential Exposure |

|---|---|

| filetype:xls username password email | Passwords |

| filetype:xls inurl: “password.xls” | Passwords |

| filetype:xls private | Private data (use as base search) |

| Inurl:admin filetype:xls | Administrative data |

| fitetype:xls inurl:contact | Contact information, e-mail addresses |

| filetype:xls inurl:“email.xls” | E-mail addresses, names |

| allinurl: admin mdb | Administrative database |

| filetype:mdb inurl:users.mdb | User lists, e-mail addresses |

| Inurl:email filetype:mdb | User lists, e-mail addresses |

| Data filetype:mdb | Various data (use as base search) |

| Inurl:backup filetype:mdb | Backup databases |

| Inurl:profiles filetype:mdb | User profiles |

| Inurl:*db filetype:mdb | Various data (use as base search) |

Database Digging

There has been intense focus recently on the security of Web-based database applications, specifically the front-end software that interfaces with a database. Within the security community, talk of SQL injection has all but replaced talk of the once-common CGI vulnerability, indicating that databases have arguably become a greater target than the underlying operating system or Web server software.

An attacker will not generally use Google to break into a database or muck with a database front-end application; rather, Google hackers troll the Internet looking for bits and pieces of database information leaked from potentially vulnerable servers. These bits and pieces of information can be used to first select a target and then to mount a more educated attack (as opposed to a ground-zero blind attack) against the target. Bearing this in mind, understand that here we do not discuss the actual mechanics of the attack itself, but rather the surprisingly invasive information-gathering phase an accomplished Google hacker will employ prior to attacking a target.

Login Portals

As we discussed in Chapter 8, a login portal is the “front door” of a Web-based application. Proudly displaying a username and password dialog, login portals generally bear the scrutiny of most Web attackers simply because they are the one part of an application that is most carefully secured. There are obvious exceptions to this rule, but as an analogy, if you’re going to secure your home, aren’t you going to first make sure your front door is secure?

A typical database login portal is shown in Figure 4.7. This login page announces not only the existence of an SQL Server but also the Microsoft Web Data Administrator software package.

Regardless of its relative strength, the mere existence of a login portal provides a glimpse into the type of software and hardware that might be employed at a target. Put simply, a login portal is terrific for footprinting. In extreme cases, an unsecured login portal serves as a welcome mat for an attacker. To this end, let’s look at some queries that an attacker might use to locate database front ends on the Internet. Table 4.5 lists queries that locate database front ends or interfaces. Most entries are pulled from the GHDB.

Table 4.5 Queries That Locate Database Interfaces

One way to locate login portals is to focus on the word login. Another way is to focus on the copyright at the bottom of a page. Most big-name portals put a copyright notice at the bottom of the page. Combine this with the product name, and a welcome or two, and you’re off to a good start. If you run out of ideas for new databases to try, go to http://labs.google.com/sets, enter oracle and mysql, and click Large Set for a list of databases.

Support Files

Another way an attacker can locate or gather information about a database is by querying for support files that are installed with, accompany, or are created by the database software. These can include configuration files, debugging scripts, and even sample database files. Table 4.6 lists some searches that locate specific support files that are included with or are created by popular database clients and servers.

Table 4.6 Queries That Locate Database Support Files

| Query | Description |

|---|---|

| inurl:default_content.asp ClearQuest | ClearQuest Web help files |

| intitle:“index of” intext:globals.inc | MySQL globals.inc file, lists connection and credential information |

| filetype:inc intext:mysql_connect | PHP MySQL Connect file, lists connection and credential information |

| filetype:inc dbconn | Database connection file, lists connection and credential information |

| intitle:“index of” intext:connect:inc | MySQL connection file, lists connection and credential information |

| filetype:properties inurl:db intext:password | db.properties file, lists connection information |

| intitle:“index of” mysql.conf OR mysql_config | MySQL configuration file, lists port number, version number, and path information to MySQL server |

| inurl:php.ini filetype.ini | PHP.INI file, lists connection and credential information |

| filetype:ldb admin | Microsoft Access lock files, list database and username |

| inurl:config.php dbuname dbpass | The old config.php script, lists user and password information |

| intitle:index.of config.php | The config.php script, lists user and password information |

| “phpinfo.php” -manual | The output from phpinfo.php, lists a great deal of information |

| intitle:“index of” +myd size | The MySQL data directory |

| filetype:cnf my.cnf -cvs -example | The MySQL my.cnf file, can list information, ranging from paths and database names to passwords and usernames |

| filetype:ora ora | ORA configuration files, list Oracle database information |

| filetype:pass pass intext:userid | dbman files, list encoded passwords |

| filetype:pdb pdb backup (Pilot | Pluckerdb) | Palm database files, can list all sorts of personal information |

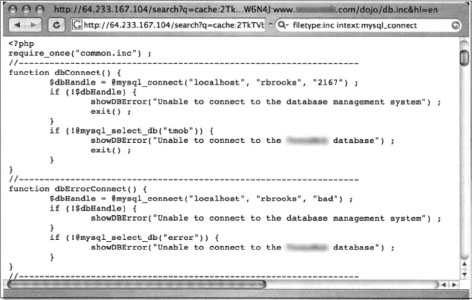

As an example of a support file, PHP scripts using the mysql_connect function reveal machine names, usernames, and cleartext passwords, as shown in Figure 4.8. Strictly speaking, this file contains PHP code, but the INC extension makes it an include file. It’s the content of this file that is of interest to a Google hacker.

Error Messages

As we’ve discussed throughout this book, error messages can be used for all sorts of profiling and information-gathering purposes. Error messages also play a key role in the detection and profiling of database systems. As is the case with most error messages, database error messages can also be used to profile the operating system and Web server version. Conversely, operating system and Web server error messages can be used to profile and detect database servers. Table 4.7 shows queries that leverage database error messages.

Table 4.7 Queries That Locate Database Error Messages

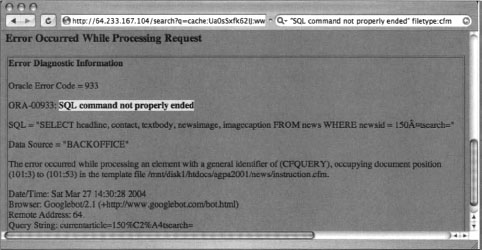

In addition to revealing information about the database server, error messages can also reveal much more dangerous information about potential vulnerabilities that exist in the server. For example, consider an error such as “SQL command not properly ended”, displayed in Figure 4.9. This error message indicates that a terminating character was not found at the end of an SQL statement. If a command accepts user input, an attacker could leverage the information in this error message to execute an SQL injection attack.

Database Dumps

The output of a database into any format can be constituted as a database dump. For the purposes of Google hacking, however, we’ll us the term database dump to describe the text-based conversion of a database. As we’ll see next in this chapter, it’s entirely possible for an attacker to locate just about any type of binary database file, but standardized formats (such as the text-based SQL dump shown in Figure 4.10) are very commonplace on the Internet.

Using a full database dump, a database administrator can completely rebuild a database. This means that a full dump details not only the structure of the database’s tables but also every record in each and every table. Depending on the sensitivity of the data contained in the database, a database dump can be very revealing and obviously makes a terrific tool for an attacker. There are several ways an attacker can locate database dumps. One of the most obvious ways is by focusing on the headers of the dump, resulting in a query such as “#Dumping data for table”, as shown in Figure 4.10. This technique can be expanded to work on just about any type of database dump headers by simply focusing on headers that exist in every dump and that are unique phrases that are unlikely to produce false positives.

Specifying additional specific interesting words or phrases such as username, password, or user can help narrow this search. For example, if the word password exists in a database dump, there’s a good chance that a password of some sort is listed inside the database dump. With proper use of the OR symbol (|), an attacker can craft an extremely effective search, such as “# Dumping data for table” (user | usemame | pass | password). In addition, an attacker could focus on file extensions that some tools add to the end of a database dump by querying for filetype:sql sql and further narrowing to specific words, phrases, or sites. The SQL file extension is also used as a generic description of batched SQL commands. Table 4.8 lists queries that locate SQL database dumps.

Table 4.8 Queries That Locate SQL Database Dumps

| Query | Description |

|---|---|

| inurl:nuke filetype:sql | php-nuke or postnuke CMS dumps |

| filetype:sql password mands | SQL database dumps or batched SQL corn- |

| filetype:sql “IDENTIFIED BY” -cvs | SQL database dumps or batched SQL commands, focus on “IDENTIFIED BY”, which can locate passwords |

| “# Dumping data for table (usernameuseruserspassword)” | SQL database dumps or batched SQL commands, focus on interesting terms |

| “#mysql dump” filetype:sql | SQL database dumps |

| “# Dumping data for table” | SQL database dumps |

| “# phpMyAdmin MySQL-Dump” filetype:txt | SQL database dumps created by phpMyAdmin |

| “# phpMyAdmin MySQL-Dump” “INSERT INTO” -"the” | SQL database dumps created by phpMyAdmin (variation) |

Actual Database Files

Another way an attacker can locate databases is by searching directly for the database itself. This technique does not apply to all database systems, only those systems in which the database is represented by a file with a specific name or extension. Be advised that Google will most likely not understand how to process or translate these files, and the summary (or “snippet”) on the search result page will be blank and Google will list the file as an “unknown type,” as shown in Figure 4.11.

If Google does not understand the format of a binary file, as with many of those located with the filetype operator, you will be unable to search for strings within that file. This considerably limits the options for effective searching, forcing you to rely on inurl or site operators instead. Table 4.9 lists some queries that can locate database files.

Table 4.9 Queries That Locate Database Files

| Query | Description |

|---|---|

| filetype:cfm “cfapplication name” password | ColdFusion source code |

| filetype:mdb inurhusers.mdb | Microsoft Access user database |

| inurl:email filetype:mdb | Microsoft Access e-mail database |

| inurl:backup filetype:mdb | Microsoft Access backup databases |

| inurl:forum filetype:mdb | Microsoft Access forum databases |

| inurl:/db/main.mdb | ASP-Nuke databases |

| inurl:profiles filetype:mdb | Microsoft Access user profile databases |

| filetype:asp DBQ=” * Server. | Microsoft Access database connection |

| MapPath(”*.mdb”) | string search |

| allinurl: admin mdb | Microsoft Access administration databases |

Automated Grinding

Searching for files is fairly straightforward—especially if you know the type of file you’re looking for. We’ve already seen how easy it is to locate files that contain sensitive data, but in some cases it might be necessary to search files offline. For example, assume that we want to troll for yahoo.com e-mail addresses. A query such as “@yahoo.com;” email is not at all effective as a Web search, and even as a Group search it is problematic, as shown in Figure 4.12.

This search located one e-mail address, [email protected], but also keyed on store.yahoo.com, which is not a valid e-mail address. In cases like this, the best option for locating specific strings lies in the use of regular expressions. This involves downloading the documents you want to search (which you most likely found with a Google search) and parsing those files for the information you’re looking for. You could opt to automate the process of downloading these files, as we’ll show in Chapter 12, but once you have downloaded the files, you’ll need an easy way to search the files for interesting information. Consider the following Perl script:

This script accepts two arguments: a file to search and a list of words to search for. As it stands, this program is rather simplistic, acting as nothing more than a glorified grep script. However, the script becomes much more powerful when instead of words, the word list contains regular expressions. For example, consider the following regular expression, written by Don Ranta:

[a-zA-Z0–9._-]+@(([a-zA-Z0–9_-]{2,99}.) + [a-zA-Z]{2,4}) | ((25 [0–5] | 2 [0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25[0–5] [2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2 [0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] | 2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]))

Unless you’re somewhat skilled with regular expressions, this might look like a bunch of garbage text. This regular expression is very powerful, however, and will locate various forms of e-mail address.

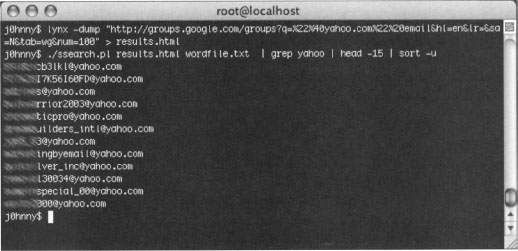

Let’s take a look at this regular expression in action. For this example, we’ll save the results of a Google Groups search for “@yahoo.com” email to a file called results.html, and we’ll enter the preceding regular expression all on one line of a file called wordlfile.txt. As shown in Figure 4.13, we can grab the search results from the command line with a program like Lynx, a common text-based Web browser. Other programs could be used instead of Lynx—Curl, Netcat, Telnet, or even “save as” from a standard Web browser. Remember that Google’s terms of service frown on any form of automation. In essence, Google prefers that you simply execute your search from the browser, saving the results manually. However, as we’ve discussed previously, if you honor the spirit of the terms of service, taking care not to abuse Google’s free search service with excessive automation, the folks at Google will most likely not turn their wrath upon you. Regardless, most people will ultimately decide for themselves how strictly to follow the terms of service.

Back to our Google search: Notice that the URL indicates we’re grabbing the first hundred results, as demonstrated by the use of the num=100 parameter. This will potentially locate more e-mail addresses. Once the results are saved to the results.html file, we’ll run our ssearch.pl script against the results.html file, searching for the e-mail expression we’ve placed in the wordfile.txt file. To help narrow our results, we’ll pipe that output into “grep yahoo | head — 15 | sort — u” to return at most 15 unique addresses that contain the word yahoo.The final (obfuscated) results are shown in Figure 4.13.

As you can see, this combination of commands works fairly well at unearthing e-mail addresses. If you’re familiar with UNIX commands, you might have already noticed that there is little need for two separate commands. This entire process could have been easily combined into one command by modifying the Perl script to read standard input and piping the output from the Lynx command directly into the ssearch.pl script, effectively bypassing the results.html file. Presenting the commands this way, however, opens the door for irresponsible automation techniques, which isn’t overtly encouraged.

Other regular expressions can come in handy as well. This expression, also by Don Ranta, locates URLs:

[a-zA-Z]{3,4}[sS]?://((([wd-]+.)+[a-zA-Z]{2,4}) | ((25 [0–5] |2 [0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]))) ((?|/) [w/=+#_˜&:;%-?.]*)*

This expression, which will locate URLs and parameters, including addresses that consist of either IP addresses or domain names, is great at processing a Google results page, returning all the links on the page. This doesn’t work as well as the API-based methods, but it is simpler to use than the API method. This expression locates IP addresses:

(25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9]). (25 [0–5] |2[0–4]d|1dd| [1–9]d| [1–9])

We can use an expression like this to help map a target network. These techniques could be used to parse not only HTML pages but also practically any type of document. However, keep in mind that many files are binary, meaning that they should be converted into text before they’re searched. The UNIX strings command (usually implemented with strings —8 for this purpose) works very well for this task, but don’t forget that Google has the built-in capability to translate many different types of documents for you. If you’re searching for visible text, you should opt to use Google’s translation, but if you’re searching for nonprinted text such as metadata, you’ll need to first download the original file and search it offline. Regardless of how you implement these techniques, it should be clear to you by now that Google can be used as an extremely powerful information-gathering tool when it’s combined with even a little automation.

Google Desktop Search

The Google Desktop, available from http://desktop.google.com, is an application that allows you to search files on your local machine. Available for Windows Mac and Linux, Google Desktop Search allows you to search many types of files, depending on the operating system you are running. The following fil types can be searched from the Mac OS X operating system:

Gmail messages

Gmail messages Text files (.txt)

Text files (.txt) PDF files

PDF files HTML files

HTML files Apple Mail and Microsoft Entourage emails

Apple Mail and Microsoft Entourage emails iChat transcripts

iChat transcripts Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents

Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents Music and Video files

Music and Video files Address Book contacts

Address Book contacts System Preference panes

System Preference panes File and folder names

File and folder names

Google Desktop Search will also search file types on a Windows operating system:

Gmail

Gmail Outlook Express

Outlook Express Word

Word Excel

Excel PowerPoint

PowerPoint Internet Explorer

Internet Explorer AOL Instant Messenger

AOL Instant Messenger MSN Messenger

MSN Messenger Google Talk

Google Talk Netscape Mail/Thunderbird

Netscape Mail/Thunderbird Netscape / Firefox / Mozilla

Netscape / Firefox / Mozilla PDF

PDF Music

Music Video

Video Images

Images Zip Files

Zip Files

The Google Desktop search offers many features, but since it’s a beta product, you should check the desktop Web page for a current list of features. For a document-grinding tool, you can simply download content from the target server and use Desktop Search to search through those files. Desktop Search also captures Web pages that are viewed in Internet Explorer 5 and newer. This means you can always view an older version of a page you’ve visited online, even when the original page has changed. In addition, once Desktop Search is installed, any online Google Search you perform in Internet Explorer will also return results found on your local machine.

Summary

The subject of document grinding is topic worthy of an entire book. In a single chapter, we can only hope to skim the surface of this topic. An attacker (black or white hat) who is skilled in the art of document grinding can glean loads of information about a target. In this chapter we’ve discussed the value of configuration files, log files, and office documents, but obviously there are many other types of documents we could focus on as well. The key to document grinding is first discovering the types of documents that exist on a target and then, depending on the number of results, to narrow the search to the more interesting or relevant documents. Depending on the target, the line of business they’re in, the document type, and many other factors, various keywords can be mixed with filetype searches to locate key documents.

Database hacking is also a topic for an entire book. However, there is obvious benefit to the information Google can provide prior to a full-blown database audit. Login portals, support files, and database dumps can provide various information that can be recycled into an audit. Of all the information that can be found from these sources, perhaps the most telling (and devastating) is source code. Lines of source code provide insight into the way a database is structured and can reveal flaws that might otherwise go unnoticed from an external assessment. In most cases, though, a thorough code review is required to determine application flaws. Error messages can also reveal a great deal of information to an attacker.

Automated grinding allows you to search many documents programmatically for bits of important information. When it’s combined with Google’s excellent document location features, you’ve got a very powerful information-gathering weapon at your disposal.

Solutions Fast Track

Configuration Files

Log Files

Office Documents

Database Digging

Links to Sites

www.filext.com A great resource for getting information about file extensions.

www.filext.com A great resource for getting information about file extensions. http://desktop.google.com The Google Desktop Search application.

http://desktop.google.com The Google Desktop Search application. http://johnny.ihackstuff.com The home of the Google Hacking Database, where you can find more searches like those listed in this chapter.

http://johnny.ihackstuff.com The home of the Google Hacking Database, where you can find more searches like those listed in this chapter.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following Frequently Asked Questions, answered by the authors of this book, are designed to both measure your understanding of the concepts presented in this chapter and to assist you with real-life implementation of these concepts. To have your questions about this chapter answered by the author, browse to www.syngress.com/solutions and click on the “Ask the Author” form.