Chapter 1Google Searching Basics

Solutions in this chapter:

Exploring Google’s Web-based Interface

Exploring Google’s Web-based Interface Building Google Queries

Building Google Queries Working With Google URLs

Working With Google URLs

Introduction

Google’s Web interface is unmistakable. Its “look and feel” is copyright-protected, and for good reason. It is clean and simple. What most people fail to realize is that the interface is also extremely powerful. Throughout this book, we will see how you can use Google to uncover truly amazing things. However, as in most things in life, before you can run, you must learn to walk.

This chapter takes a look at the basics of Google searching. We begin by exploring the powerful Web-based interface that has made Google a household word. Even the most advanced Google users still rely on the Web-based interface for the majority of their day-today queries. Once we understand how to navigate and interpret the results from the various interfaces, we will explore basic search techniques.

Understanding basic search techniques will help us build a firm foundation on which to base more advanced queries. You will learn how to properly use the Boolean operators (AND, NOT, and OR) as well as exploring the power and flexibility of grouping searches. We will also learn Google’s unique implementation of several different wildcard characters.

Finally, you will learn the syntax of Google’s Uniform Resource Locator (URL) structure. Learning the ins and outs of the Google URL will give you access to greater speed and flexibility when submitting a series of related Google searches. We will see that the Google URL structure provides an excellent “shorthand” for exchanging interesting searches with friends and colleagues.

Exploring Google’s Web-based Interface

Google’s Web Search Page

The main Google Web page, shown in Figure 1.1, can be found at www.google.com. The interface is known for its clean lines, pleasingly uncluttered feel, and friendly interface. Although the interface might seem relatively featureless at first glance, we will see that many different search functions can be performed right from this first page.

As shown in Figure 1.1, there’s only one place to type. This is the search field. In order to ask Google a question or query, you simply type what you’re looking for and either press Enter (if your browser supports it) or click the Google Search button to be taken to the results page for your query.

The links at the top of the screen (Web, Images, Video, and so on) open the other search areas shown in Table 1.1. The basic search functionality of each section is the same: each search area of the Google Web interface has different capabilities and accepts different search operators, as we will see in Chapter 2. For example, the author operator works well in Google Groups, but may fail in other search areas. Table 1.1 outlines the functionality of each distinct area of the main Google Web page.

Table 1.1 The Links and Functions of Google’s Main Page

| Interface Section | Description |

|---|---|

| The Google toolbar | The browser I am using has a Google “toolbar” installed and presented next to the address bar. We will take a look at various Google toolbars in the next section. |

| Web, Images, Video, News, Maps, Gmail and more tabs | These tabs allow you to search Web pages, photographs, message group postings, Google maps, and Google Mail, respectively. If you are a first-time Google user, understand that these tabs are not always a replacement for the Submit Search button. These tabs simply whisk you away to other Google search applications. |

| iGoogle | This link takes you to your personal Google home page. |

| Sign in | This link allows you to sign in to access additional functionality by logging in to your Google Account. |

| Search term input field | Located directly below the alternate search tabs, this text field allows you to enter a Google search term. We will discuss the syntax of Google searching throughout this book. |

| Google Search button | This button submits your search term. In many browsers, simply pressing the Enter/Return key after typing a search term will activate this button. |

| I’m Feeling Lucky button | Instead of presenting a list of search results, this button will forward you to the highest-ranked page for the entered search term. Often this page is the most relevant page for the entered search term. |

| Advanced Search | This link takes you to the Advanced Search page as shown. We will look at these advanced search options in Chapter 2. |

| Preferences | This link allows you to select several options (which are stored in cookies on your machine for later retrieval). Available options include language selection, parental filters, number of results per page, and window options. |

| Language tools | This link allows you to set many different language options and translate text to and from various languages. |

Google Web Results Page

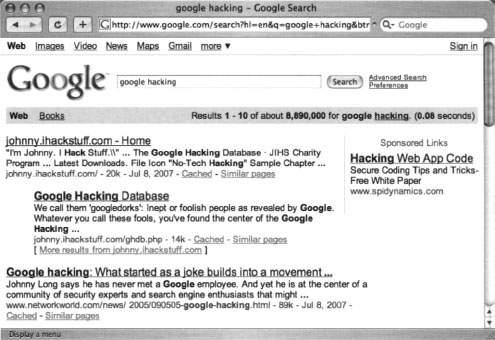

After it processes a search query, Google displays a results page. The results page, shown in Figure 1.2, lists the results of your search and provides links to the Web pages that contain your search text.

The top part of the search result page mimics the main Web search page. Notice the Images, Video, News, Maps, and Gmail links at the top of the page. By clicking these links from a search page, you automatically resubmit your search as another type of search, without having to retype your query.

The results line shows which results are displayed (1–10, in this case), the approximate total number of matches (here, over eight million), the search query itself (including links to dictionary lookups of individual words), and the amount of time the query took to execute. The speed of the query is often overlooked, but it is quite impressive. Even large queries resulting in millions of hits are returned within a fraction of a second!

For each entry on the results page, Google lists the name of the site, a summary of the site (usually the first few lines of content), the URL of the page that matched, the size and date the page was last crawled, a cached link that shows the page as it appeared when Google last crawled it, and a link to pages with similar content. If the result page is written in a language other than your native language and Google supports the translation from that language into yours (set in the preferences screen), a link titled Translate this page will appear, allowing you to read an approximation of that page in your own language (see Figure 1.3).

It’s possible to use Google as a transparent proxy server via the translation service. When you click a Translate this page link, you are taken to a translated copy of that page hosted on Google’s servers. This serves as a sort of proxy server, fetching the page on your behalf. If the page you want to view requires no translation, you can still use the translation service as a proxy server by modifying the hl variable in the URL to match the native language of the page. Bear in mind that images are not proxied in this manner.

Google Groups

Due to the surge in popularity of Web-based discussion forums, blogs, mailing lists, and instant-messaging technologies, USENET newsgroups, the oldest of public discussion forums, have become an overlooked form of online public discussion. Thousands of users still post to USENET on a daily basis. A thorough discussion about what USENET encompasses can be found at www.faqs.org/faqs/usenet/what-is/partl/.DejaNews (www.deja.com) was once considered the authoritative collection point for all past and present newsgroup messages until Google acquired deja.com in February 2001 (see www.google.com/press/pressrel/pressrelease48.html).This acquisition gave users the ability to search the entire archive of USENET messages posted since 1995 via the simple, straightforward Google search interface. Google refers to USENET groups as Google Groups. Today, Internet users around the globe turn to Google Groups for general discussion and problem solving. It is very common for Information Technology (IT) practitioners to turn to Google’s Groups section for answers to all sorts of technology-related issues. The old USENET community still thrives and flourishes behind the sleek interface of the Google Groups search engine.

The Google Groups search can be accessed by clicking the Groups tab of the main Google Web page or by surfing to http://groups.google.com. The search interface (shown in Figure 1.4) looks quite a bit different from other Google search pages, yet the search capabilities operate in much the same way. The major difference between the Groups search page and the Web search page lies in the newsgroup browsing links.

Entering a search term into the entry field and clicking the Search button whisks you away to the Groups search results page, which is very similar to the Web search results page.

Google Image Search

The Google Image search feature allows you to search (at the time of this writing) over a billion graphic files that match your search criteria. Google will attempt to locate your search terms in the image filename, in the image caption, in the text surrounding the image, and in other undisclosed locations, to return a somewhat “de-duplicated” list of images that match your search criteria. The Google Image search operates identically to the Web search, with the exception of a few of the advanced search terms, which we will discuss in the next chapter. The search results page is also slightly different, as you can see in Figure 1.5.

The page header looks familiar, but contains a few additions unique to the search results page. The Moderate SafeSearch link below the search field allows you to enable or disable images that may be sexually explicit. The Showing dropdown box (located in the Results line) allows you to narrow image results by size. Below the header, each matching image is shown in a thumbnail view with the original resolution and size followed by the name of the site that hosts the image.

Google Preferences

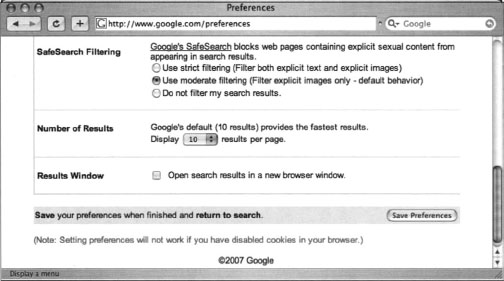

You can access the Preferences page by clicking the Preferences link from any Google search page or by browsing to www.google.com/preferences. These options primarily pertain to language and locality settings, as shown in Figure 1.6.

The Interface Language option describes the language that Google will use when printing tips and informational messages. In addition, this setting controls the language of text printed on Google’s navigation items, such as buttons and links. Google assumes that the language you select here is your native language and will “speak” to you in this language whenever possible. Setting this option is not the same as using the translation features of Google (discussed in the following section). Web pages written in French will still appear in French, regardless of what you select here.

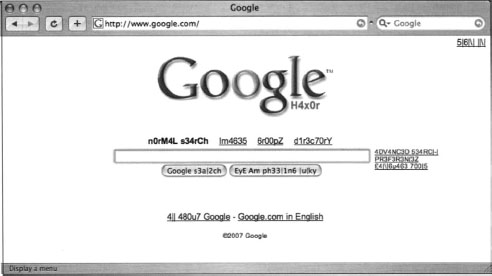

To get an idea of how Google’s Web pages would be altered by a change in the interface language, take a look at Figure 1.7 to see Google’s main page rendered in “hacker speak.” In addition to changing this setting on the preferences screen, you can access all the language-specific Google interfaces directly from the Language Tools screen at www.google.com/language_tools.

Even though the main Google Web page is now rendered in “hacker speak,” Google is still searching for Web pages written in any language. If you are interested in locating Web pages that are written in a particular language, modify the Search Language setting on the Google preferences page. By default, Google will always try to locate Web pages written in any language.

As we will see in later chapters, proxy servers can be used to help hide your location and identity while you’re surfing the Web. Depending on the geographical location of a proxy server, the language settings of the main Google page may change to match the language of the country where the proxy server is located. If your language settings change inexplicably, be sure to check your proxy server settings. Even experienced proxy users can lose track of when a proxy is enabled and when it’s not. As we will see later, language settings can be modified directly via the URL.

The preferences screen also allows you to modify other search parameters, as shown in Figure 1.8.

SafeSearch Filtering blocks explicit sexual content from appearing in Web searches. Although this is a welcome option for day-to-day Web searching, this option should be disabled when you’re performing searches as part of a vulnerability assessment. If sexually explicit content exists on a Web site whose primary content is not sexual in nature, the existence of this material may be of interest to the site owner.

The Number of Results setting describes how many results are displayed on each search result page. This option is highly subjective, based on your tastes and Internet connection speed. However, you may quickly discover that the default setting of 10 hits per page is simply not enough. If you’re on a relatively fast connection, you should consider setting this to 100, the maximum number of results per page.

When checked, the Results Window setting opens search results in a new browser window. This setting is subjective based on your personal tastes. Checking or unchecking this option should have no ill effects unless your browser (or other software) detects the new window as a pop-up advertisement and blocks it. If you notice that your Google results pages are not displaying after you click the Search button, you might want to uncheck this setting in your Google preferences.

As noted at the bottom of this page, these changes won’t stick unless you have enabled cookies in your browser.

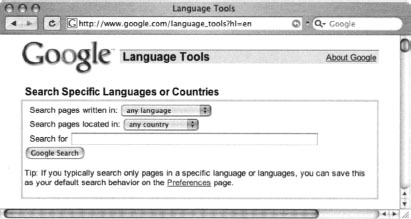

Language Tools

The Language Tools screen, accessed from the main Google page, offers several different utilities for locating and translating Web pages written in different languages. If you rarely search for Web pages written in other languages, it can become cumbersome to modify your preferences before performing this type of search. The first portion of the Language Tools screen (shown in Figure 1.9) allows you to perform a quick search for documents written in other languages as well as documents located in other countries.

The Language Tools screen also includes a utility that performs basic translation services. The translation form (shown in Figure 1.10) allows you to paste a block of text from the clipboard or supply a Web address to a page that Google will translate into a variety of languages.

In addition to the translation options available from this screen, Google integrates translation options into the search results page, as we will see in more detail. The translation options available from the search results page are based on the language options that are set from the Preferences screen shown in Figure 1.6. In other words, if your interface language is set to English and a Web page listed in a search result is French, Google will give you the option to translate that page into your native language, English. The list of available language translations is shown in Figure 1.11.

Don’t get distracted by the allure of Google “helper” programs such as browser toolbars. All the important search features are available right from the main Google search screen. Each toolbar offers minor conveniences such as one-click directory traversals or select-and-search capability, but there are so many different toolbars available, you’ll have to decide for yourself which one is right for you and your operating environment. Check the Web links at the end of this section for a list of some popular alternatives.

Building Google Queries

Google query building is a process. There’s really no such thing as an incorrect search. It’s entirely possible to create an ineffective search, but with the explosive growth of the Internet and the size of Google’s cache, a query that’s inefficient today may just provide good results tomorrow—or next month or next year. The idea behind effective Google searching is to get a firm grasp on the basic syntax and then to get a good grasp of effective narrowing techniques. Learning the Google query syntax is the easy part. Learning to effectively narrow searches can take quite a bit of time and requires a bit of practice. Eventually, you’ll get a feel for it, and it will become second nature to find the needle in the haystack.

The Golden Rules of Google Searching

Before we discuss Google searching, we should understand some of the basic ground rules:

Google queries are not case sensitive. Google doesn’t care if you type your query in lowercase letters (hackers), uppercase (HACKERS), camel case (hAcKeR), or psycho-case (haCKeR)—the word is always regarded the same way. This is especially important when you’re searching things like source code listings, when the case of the term carries a great deal of meaning for the programmer. The one notable exception is the word or. When used as the Boolean operator, or must be written in uppercase, as OR.

Google queries are not case sensitive. Google doesn’t care if you type your query in lowercase letters (hackers), uppercase (HACKERS), camel case (hAcKeR), or psycho-case (haCKeR)—the word is always regarded the same way. This is especially important when you’re searching things like source code listings, when the case of the term carries a great deal of meaning for the programmer. The one notable exception is the word or. When used as the Boolean operator, or must be written in uppercase, as OR. Google -wildcards. Google’s concept of wildcards is not the same as a programmer’s concept of wildcards. Most consider wildcards to be either a symbolic representation of any single letter (UNIX fans may think of the question mark) or any series of letters represented by an asterisk. This type of technique is called stemming. Google’s wildcard, the asterisk (*), represents nothing more than a single word in a search phrase. Using an asterisk at the beginning or end of a word will not provide you any more hits than using the word by itself.

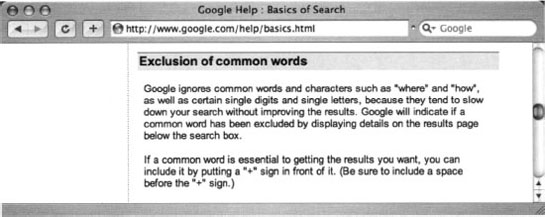

Google -wildcards. Google’s concept of wildcards is not the same as a programmer’s concept of wildcards. Most consider wildcards to be either a symbolic representation of any single letter (UNIX fans may think of the question mark) or any series of letters represented by an asterisk. This type of technique is called stemming. Google’s wildcard, the asterisk (*), represents nothing more than a single word in a search phrase. Using an asterisk at the beginning or end of a word will not provide you any more hits than using the word by itself. Google reserves the right to ignore you. Google ignores certain common words, characters, and single digits in a search. These are sometimes called stop words. According to Google’s basic search document (www.google.com/help/basics.html), these words include where and how, as shown in Figure 1.12. However, Google does seem to include those words in a search. For example, a search for WHERE 1 = 1 returns less results than a search for 1 = 1. This is an indication that the WHERE is being included in the search. A search for where pig returns significantly less results than a simple search for pig, again an indication that Google does in fact include words like how and where. Sometimes Google will silently ignore these stop words. For example, a search for HOW 1 = WHERE 4 returns the same number of results as a query for 1 = WHERE 4. This seems to indicate that the word HOW is irrelevant to the search results, and that Google silently ignored the word. There are no obvious rules for word exclusion, but sometimes when Google ignores a search term, a notification will appear on the results page just below the query box.

Google reserves the right to ignore you. Google ignores certain common words, characters, and single digits in a search. These are sometimes called stop words. According to Google’s basic search document (www.google.com/help/basics.html), these words include where and how, as shown in Figure 1.12. However, Google does seem to include those words in a search. For example, a search for WHERE 1 = 1 returns less results than a search for 1 = 1. This is an indication that the WHERE is being included in the search. A search for where pig returns significantly less results than a simple search for pig, again an indication that Google does in fact include words like how and where. Sometimes Google will silently ignore these stop words. For example, a search for HOW 1 = WHERE 4 returns the same number of results as a query for 1 = WHERE 4. This seems to indicate that the word HOW is irrelevant to the search results, and that Google silently ignored the word. There are no obvious rules for word exclusion, but sometimes when Google ignores a search term, a notification will appear on the results page just below the query box.

One way to force Google into using common words is to include them in quotes. Doing so submits the search as a phrase, and results will include all the words in the term, regardless of how common they may be. You can also precede the term with a + sign, as in the query +and. Submitted without the quotes, taking care not to put a space between the + and the word and, this search returns nearly five billion results!

One very interesting search is the search for of*. This search produces somewhere in the neighborhood of eighteen billion search results, making it one of the most prolific searches known! Can you top this search?

32–word limit Google limits searches to 32 words, which is up from the previous limit often words. This includes search terms as well as advanced operators, which we’ll discuss in a moment. While this is sufficient for most users, there are ways to get beyond that limit. One way is to replace some terms with the wildcard character (*). Google does not count the wildcard character as a search term, allowing you to extend your searches quite a bit. Consider a query for the wording of the beginning of the U.S. Constitution:

32–word limit Google limits searches to 32 words, which is up from the previous limit often words. This includes search terms as well as advanced operators, which we’ll discuss in a moment. While this is sufficient for most users, there are ways to get beyond that limit. One way is to replace some terms with the wildcard character (*). Google does not count the wildcard character as a search term, allowing you to extend your searches quite a bit. Consider a query for the wording of the beginning of the U.S. Constitution:

we the people of the united states in order to form a more perfect union establish justice

This search term is seventeen words long. If we replace some of the words with the asterisk (the wildcard character) and submit it as

“we * people * * united states * order * form * more perfect * establish *”

including the quotes, Google sees this as a nine-word query (with eight uncounted wildcard characters). We could extend our search even farther, by two more real words and just about any number of wildcards.

Basic Searching

Google searching is a process, the goal of which is to find information about a topic. The process begins with a basic search, which is modified in a variety of ways until only the pages of relevant information are returned. Google’s ranking technology helps this process along by placing the highest-ranking pages on the first results page. The details of this ranking system are complex and somewhat speculative, but suffice it to say that for our purposes Google rarely gives us exactly what we need following a single search.

The simplest Google query consists of a single word or a combination of individual words typed into the search interface. Some basic word searches could include:

hacker

hacker FBI hacker Mitnick

FBI hacker Mitnick mad hacker dpak

mad hacker dpak

Slightly more complex than a word search is a phrase search. A phrase is a group of words enclosed in double-quote marks. When Google encounters a phrase, it searches for all words in the phrase, in the exact order you provide them. Google does not exclude common words found in a phrase. Phrase searches can include

“Google hacker”

“Google hacker” “adult humor”

“adult humor” “Carolina gets pwnt”

“Carolina gets pwnt”

Phrase and word searches can be combined and used with advanced operators, as we will see in the next chapter.

Using Boolean Operators and Special Characters

More advanced than basic word searches, phrase searches are still a basic form of a Google query. To perform advanced queries, it is necessary to understand the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT. To properly segment the various parts of an advanced Google query, we must also explore visual grouping techniques that use the parenthesis characters. Finally, we will combine these techniques with certain special characters that may serve as shorthand for certain operators, wildcard characters, or placeholders.

If you have used any other Web search engines, you have probably been exposed to Boolean operators. Boolean operators help specify the results that are returned from a query. If you are already familiar with Boolean operators, take a moment to skim this section to help you understand Google’s particular implementation of these operators, since many search engines handle them in different ways. Improper use of these operators could drastically alter the results that are returned.

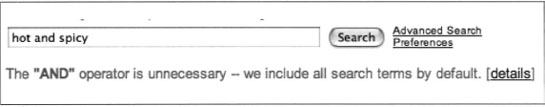

The most commonly used Boolean operator is AND. This operator is used to include multiple terms in a query. For example, a simple query like hacker could be expanded with a Boolean operator by querying for hacker AND cracker. The latter query would include not only pages that talk about hackers but also sites that talk about hackers and the snacks they might eat. Some search engines require the use of this operator, but Google does not. The term AND is redundant to Google. By default, Google automatically searches for all the terms you include in your query. In fact, Google will warn you when you have included terms that are obviously redundant, as shown in Figure 1.13.

When first learning the ways of Google-fu, keep an eye on the area below the query box on the Web interface. You’ll pick up great pointers to help you improve your query syntax.

The plus symbol (+) forces the inclusion of the word that follows it. There should be no space following the plus symbol. For example, if you were to search for and, justice, for, and all as separate, distinct words, Google would warn that several of the words are too common and are excluded from the search. To force Google to search for those common words, preface them with the plus sign. It’s okay to go overboard with the plus sign. It has no ill effects if it is used excessively. To perform this search with the inclusion of all words, consider a query such as +and justice for +all. In addition, the words could be enclosed in double quotes. This generally will force Google to include all the common words in the phrase. This query presented as a phrase would be and justice for all.

Another common Boolean operator is NOT. Functionally the opposite of the AND operator, the NOT operator excludes a word from a search. The best way to use this operator is to preface a search word with the minus sign (—). Be sure to leave no space between the minus sign and the search term. Consider a simple query such as hacker. This query is very generic and will return hits for all sorts of occupations, like golfers, woodchoppers, serial killers, and those with chronic bronchitis. With this type of query, you are most likely not interested in each and every form of the word hacker but rather a more specific rendition of the term. To narrow the search, you could include more terms, which Google would automatically AND together, or you could start narrowing the search by using NOT to remove certain terms from your search. To remove some of the more unsavory characters from your search, consider using queries such as hacker—golf or hacker —phlegm. This would allow you to get closer to the dastardly wood choppers you’re looking for. Or just try a Google Video search for lumberjack song. Talk about twisted.

A less common and sometimes more confusing Boolean operator is OR. The OR operator, represented by the pipe symbol (|)or simply the word OR in uppercase letters, instructs Google to locate either one term or another in a query. Although this seems fairly straightforward when considering a simple query such as hacker or “evil cybercriminal,” things can get terribly confusing when you string together a bunch of ANDs and ORs and NOTs. To help alleviate this confusion, don’t think of the query as anything more than a sentence read from left to right. Forget all that order of operations stuff you learned in high school algebra. For our purposes, an AND is weighed equally with an OR, which is weighed as equally as an advanced operator. These factors may affect the rank or order in which the search results appear on the page, but have no bearing on how Google handles the search query.

Let’s take a look at a very complex example, the exact mechanics of which we will discuss in Chapter 2:

intext: password | passcode intext:username | userid | user filetype: csv

This example uses advanced operators combined with the OR Boolean to create a query that reads like a sentence written as a polite request. The request reads, “Locate all pages that have either password or passcode in the text of the document. From those pages, show me only the pages that contain either the words username, userid, or user in the text of the document. From those pages, only show me documents that are CSV files.” Google doesn’t get confused by the fact that technically those OR symbols break up the query into all sorts of possible interpretations. Google isn’t bothered by the fact that from an algebraic standpoint, your query is syntactically wrong. For the purposes of learning how to create queries, all we need to remember is that Google reads our query from left to right.

Google’s cut-and-dried approach to combining Boolean operators is still very confusing to the reader. Fortunately, Google is not offended (or affected by) parenthesis. The previous query can also be submitted as

intext:(password | passcode) intext:(username | userid | user) filetype:csv

This query is infinitely more readable for us humans, and it produces exactly the same results as the more confusing query that lacked parentheses.

Search Reduction

To achieve the most relevant results, you’ll often need to narrow your search by modifying the search query. Although Google tends to provide very relevant results for most basic searches, we will begin looking at fairly complex searches aimed at locating a very narrow subset of Web sites. The vast majority of this book focuses on search reduction techniques and suggestions, but it’s important that you at least understand the basics of search reduction. As a simple example, we’ll take a look at GNU Zebra, free software that manages Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)/Internet Protocol (IP)-based routing protocols. GNU Zebra uses a file called zebra.conf to store configuration settings, including interface information and passwords. After downloading the latest version of Zebra from the Web, we learn that the included zebra.conf.sample file looks like this:

! -*- zebra -*-

! zebra sample configuration file

! $Id: zebra.conf.sample, v 1.14 1999/02/19 17:26:38 developer Exp $

hostname Router

password zebra

enable password zebra

!

! Interface’s description.

!

! interface lo

! description test of desc.

!

! interface sit0

! multicast

!

! Static default route sample.

!

!ip route 0.0.0.0/0 203.181.89.241

!

! log file zebra.log

To attempt to locate these files with Google, we might try a simple search such as:

“! Interface’s description. “

This is considered the base search. Base searches should be as unique as possible in order to get as close to our desired results as possible, remembering the old adage “Garbage in, garbage out.” Starting with a poor base search completely negates ah the hard work you’ll put into reduction. Our base search is unique not only because we have focused on the words Inteface’s and description, but we have also included the exclamation mark, the spaces, and the period following the phrase as part of our search. This is the exact syntax that the configuration file itself uses, so this seems like a very good place to start. However, Google takes some liberties with this search query, making the results less than adequate, as shown in Figure 1.14.

These results aren’t bad at all, and the query is relatively simple, but we started out looking for zebra.conf’files. So let’s add this to our search to help narrow the results. This makes our next query:

“! Interface’s description. “ zebra.conf

As Figure 1.15 shows, the results are slightly different, but not necessarily better.

For starters, the seattlewireless hit we had in our first search is missing. This was a valid hit, but because the configuration file was not named zebra.conf (it was named ZebraConfig) our “improved” search doesn’t see it. This is a great lesson to learn about search reduction: don’t reduce your way past valid results.

Notice that the third hit in Figure 1.15 references zebra.conf.sample. These sample files may clutter valid results, so we’ll add to our existing query, reducing hits that contain this phrase. This makes our new query

“! Interface’s description. “ -” zebra.conf.sample”

However, it helps to step into the shoes of the software’s users for just a moment. Software installations like this one often ship with a sample configuration file to help guide the process of setting up a custom configuration. Most users will simply edit this file, changing only the settings that need to be changed for their environments, saving the file not as a .sample file but as a .conf file. In this situation, the user could have a live configuration file with the term zebra.conf.sample still in place. Reduction based on this term may remove valid configuration files created in this manner.

There’s another reduction angle. Notice that our zebra.conf.sample file contained the term hostname Router. This is most likely one of the settings that a user will change, although we’re making an assumption that his machine is not named Router. This is less a gamble than reducing based on zebra.conf.sample, however. Adding the reduction term “hostname Router” to our query brings our results number down and reduces our hits on potential sample files, all without sacrificing potential live hits.

Although it’s certainly possible to keep reducing, often it’s enough to make just a few minor reductions that can be validated by eye than to spend too much time coming up with the perfect search reduction. Our final (that’s four qualifiers for just one word!) query becomes:

“! Interface’s description. “ -"hostname Router”

This is not the best query for locating these files, but it’s good enough to give you an idea about how search reduction works. As we’ll see in Chapter 2, advanced operators will get us even closer to that perfect query!

In some cases, there’s nothing wrong with using poor Google syntax in a search. If Google safely ignores part of a human-friendly query, leave it alone. The human readers will thank you!

Working With Google URLs

Advanced Google users begin testing advanced queries right from the Web interface’s search field, refining queries until they are just right. Every Google query can be represented with a URL that points to the results page. Google’s results pages are not static pages. They are dynamic and are created “on the fly” when you click the Search button or activate a URL that links to a results page. Submitting a search through the Web interface takes you to a results page that can be represented by a single URL. For example, consider the query ihackstuff. Once you enter this query, you are whisked away to a URL similar to the following:

www.google.com/search?q=ihackstuff

If you bookmark this URL and return to it later or simply enter the URL into your browser’s address bar, Google will reprocess your search for ihackstuff and display the results. This URL then becomes not only an active connection to a list of results, it also serves as a nice, compact sort of shorthand for a Google query. Any experienced Google searcher can take a look at this URL and realize the search subject. This URL can also be modified fairly easily. By changing the word ihackstuff to iwritestuff, the Google query is changed to find the term iwritestuff. This simple example illustrates the usefulness of the Google URL for advanced searching. A quick modification of the URL can make changes happen fast!

The only URL parameter that is required in most cases is a query (the q parameter), making the simplest Google URL www.google.com/search?q=google.

URL Syntax

To fully understand the power of the URL, we need to understand the syntax. The first part of the URL, wuw.google.com/search, is the location of Google’s search script. I refer to this URL, as well as the question mark that follows it, as the base, or starting URL. Browsing to this URL presents you with a nice, blank search page. The question mark after the word search indicates that parameters are about to be passed into the search script. Parameters are options that instruct the search script to actually do something. Parameters are separated by the ampersand (&) and consist of a variable followed by the equal sign (=) followed by the value that the variable should be set to. The basic syntax will look something like this:

www.google.com/search?variablel=value&variable2=value

This URL contains very simple characters. More complex URL’s will contain special characters, which must be represented with hex code equivalents. Let’s take a second to talk about hex encoding.

Special Characters

Hex encoding is definitely geek stuff, but sooner or later you may need to include a special character in your search URL. When that time comes, it’s best to just let your browser help you out. Most modern browsers will adjust a typed URL, replacing special characters and spaces with hex-encoded equivalents. If your browser supports this behavior, your job of URL construction is that much easier. Try this simple test. Type the following URL in your browser’s address bar, making sure to use spaces between i, hack, and stuff.

www.google.com/search?q=“i hack stuff”

If your browser supports this auto-correcting feature, after you press Enter in the address bar, the URL should be corrected to www.google.com/search?q=“i%20hack%20stuff” or something similar. Notice that the spaces were changed to %20. The percent sign indicates that the next two digits are the hexadecimal value of the space character, 20. Some browsers will take the conversion one step further, changing the double-quotes to %22 as well.

If your browser refuses to convert those spaces, the query will not work as expected. There may be a setting in your browser to modify this behavior, but if not, do yourself a favor and use a modern browser. Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, and Opera are all excellent choices.

To quickly determine hex codes for a character, you can run an American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) from a UNIX or Linux machine, or Google for the term “ascii table.”

Putting the Pieces Together

Google search URL construction is like putting together Legos. You start with a URL and you modify it as needed to achieve varying search results. Many times your base URL will come from a search you submitted via the Google Web interface. If you need some added parameters, you can add them directly to the base URL in any order. If you need to modify parameters in your search, you can change the value of the parameter and resubmit your search. If you need to remove a parameter, you can delete that entire parameter from the URL and resubmit your search. This process is especially easy if you are modifying the URL directly in your browser’s address bar. You simply make changes to the URL and press Enter. The browser will automatically fetch the address and take you to an updated search page. You could achieve similar results by poking around Google’s advanced search page (www.google.com/advanced_search, shown in Figure 1.16) and by setting various preferences, as discussed earlier, but ultimately most advanced users find it faster and easier to make quick search adjustments directly through URL modification.

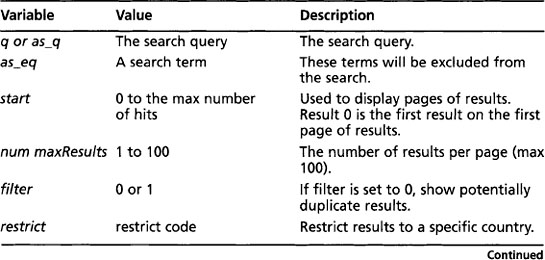

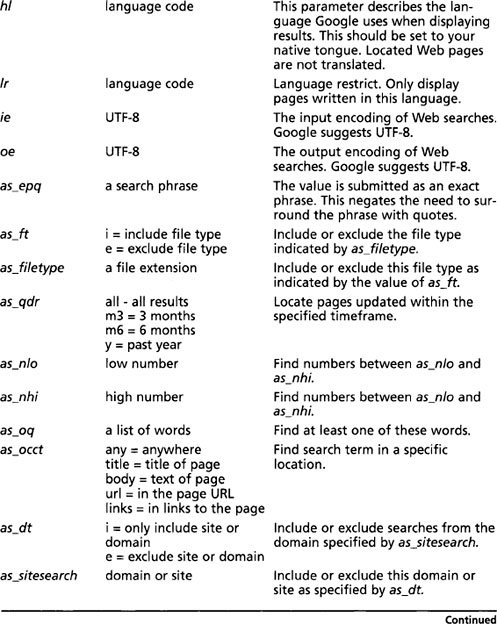

A Google search URL can contain many different parameters. Depending on the options you selected and the search terms you provided, you will see some or all of the variables listed in Table 1.2. These parameters can be added or modified as needed to change your search criteria.

Some parameters accept a language restrict (Ir) code as a value. The lr value instructs Google to only return pages written in a specific language. For example, lr=lang_ar only returns pages written in Arabic. Table 1.3 lists all the values available for the lr field:

Table 1.3 Language Restrict Codes

The hl variable changes the language of Google’s messages and links. This is not the same as the lr variable, which restricts our results to pages written in a specific language, nor is it like the translation service, which translates a page from one language to another.

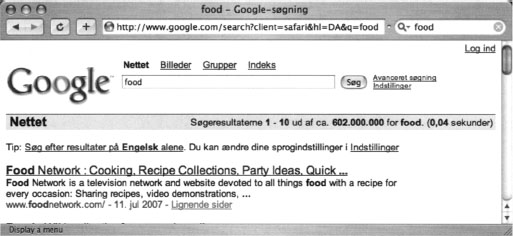

Figure 1.17 shows the results of a search for the word food with an hl variable set to DA (Danish). Notice that Google’s messages and links are in Danish, whereas the search results are written in English. We have not asked Google to restrict or modify our search in any way.

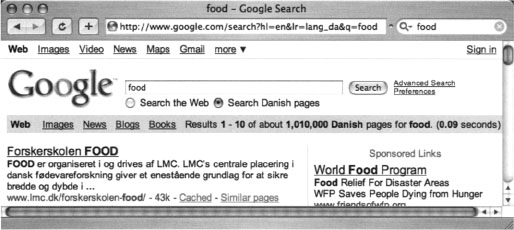

To understand the contrast between hl and lr, consider the food search resubmitted as an lr search, as shown in Figure 1.18. Notice that our URL is different: There are now far fewer results, the search results are written in Danish, Google added a Search Danish pages button, and Google’s messages and links are written in English. Unlike the hl option (Table 1.4 lists the values for the hl field), the lr option changes our search results. We have asked Google to return only pages written in Danish.

Table 1.4 hl Language Field Values

The hl value is sticky! This means that if you change this value in your URL, it sticks for future searches. The best way to change it back is through Google preferences or by changing the hl code directly inside the URL.

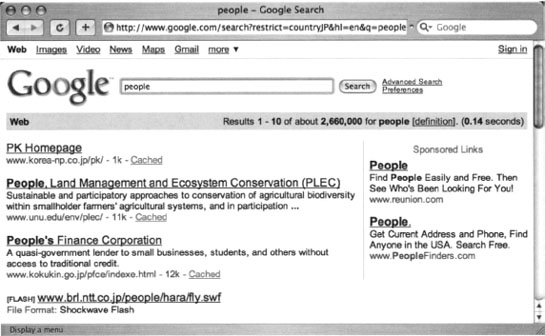

The restrict variable is easily confused with the lr variable, since it restricts your search to a particular language. However, restrict has nothing to do with language. This variable gives you the ability to restrict your search results to one or more countries, determined by the top-level domain name (.us, for example) and/or by geographic location of the server’s IP address. If you think this smells somewhat inexact, you’re right. Although inexact, this variable works amazingly well. Consider a search for people in which we restrict our results to JP (Japan), as shown in Figure 1.19. Our URL has changed to include the restrict value (shown in Table 1.5), but notice that the second hit is from www.unu.edu, the location of which is unknown. As our sidebar reveals, the host does in fact appear to be located in Japan.

It’s easy to get a relative idea of where a host is located geographically. Here’s how host and whois can be used to figure out where www.unu.edu is located:

wh00p: ˜# host www.unu.edu

www.unu.edu has address 202.253.138.42

wh00p; ˜# whois 202.253.138.42

role : Japan Network Information Center

address ; Kokusai-Kougyou-Kanda Bldg 6F, 2–3–4 Uchi-Kanda

address : Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101–0047, Japan

country: JP

phone : +81–3–5297–2311

fax-no: +81–3–5297–2312

Table 1.5 restrict Field Values

Summary

Google is deceptively simple in appearance, but offers many powerful options that provide the groundwork for powerful searches. Many different types of content can be searched, including Web pages, message groups such as USENET, images, video, and more. Beginners to Google searching are encouraged to use the Google-provided forms for searching, paying close attention to the messages and warnings Google provides about syntax. Boolean operators such as OR and NOT are available through the use of the minus sign and the word OR (or the | symbol), respectively, whereas the AND operator is ignored, since Google automatically includes all terms in a search. Advanced search options are available through the Advanced Search page, which allows users to narrow search results quickly. Advanced Google users narrow their searches through customized queries and a healthy dose of experience and good old common sense.

Solutions Fast Track

Exploring Google’s Web-based Interface

Building Google Queries

Working With Google URLs

Links to Sites

Frequently Asked Questions

The following Frequently Asked Questions, answered by the authors of this book, are designed to both measure your understanding of the concepts presented in this chapter and to assist you with real-life implementation of these concepts. To have your questions about this chapter answered by the author, browse to www.syngress.com/solutions and click on the “Ask the Author” form.

Here’s a list of some popular Google search tools:

| Platform | Tool | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Mac | Google Notifier, Google Desktop, Google Sketchup | www.google.com/mac.html |

| PC | Google Pack (includes IE & Firefox toolbars, Google Desktop and more) | www.google.com/tools |

| Mozilla Browser | Googlebar | http://googlebar.mozdev.og/ |

| Firefox, Internet Explorer | Groowe multi-engine Toolbar | www.groowe.com/ |