Uncle Sol’s Boys

Ed Roberts? You gotta give him credit for doing the first one. But give the guy [who] published him as much credit: Les Solomon.

–Chuck Peddle, computer designer

Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and other computer enthusiasts relied on the hobbyist electronics magazines like Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics to keep up with the latest technological developments. In the early 1970s, what Gates and Allen were seeing in the pages of those magazines served to frustrate them as much as excite them. Most of the magazines’ readers knew something about computers, and many knew a lot more than that—and every one of them now wanted to own a computer. The computer aficionados who read Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics were an opinionated lot; they knew precisely what they did and didn’t want in a computer.

What these enthusiasts wanted most often was more control over the machines they used. They resented having to wait in line to use the very tool of their trade or to engage in their favorite hobby. They wanted immediate access to the files they created on a computer, even if they were off somewhere on a business trip. They wanted to play computer games at their leisure without someone telling them to get back to work. In short, what these enthusiasts wanted was a personal computer. But in the early 1970s, the idea of someone owning his or her own computer was no more than a wild dream.

Your Very Own Computer

A big step toward the realization of the personal-computer dream happened in September 1973, when Radio-Electronics published an article by Don Lancaster that described a “TV Typewriter.” A prolific contributor to electronics magazines, Lancaster later published his groundbreaking idea in book form. His proposed uses for the TV Typewriter were nothing short of visionary:

“Obviously, it’s a computer terminal for time-sharing services, schools, and experimental uses. It’s a ham radio Teletype terminal. Coupled to the right services it can…display news, stock quotations, time, and weather. It’s a communications aide for the deaf. It’s a teaching machine, particularly good for helping preschoolers learn the alphabet and words. It also keeps them busy for hours as an educational toy.”

Lancaster’s TV Typewriter, for all its visionary appeal, was nevertheless only a terminal: an I/O (input/output) device that would link to a mainframe computer. It didn’t constitute the personal computer that the electronics hobbyists desperately wanted.

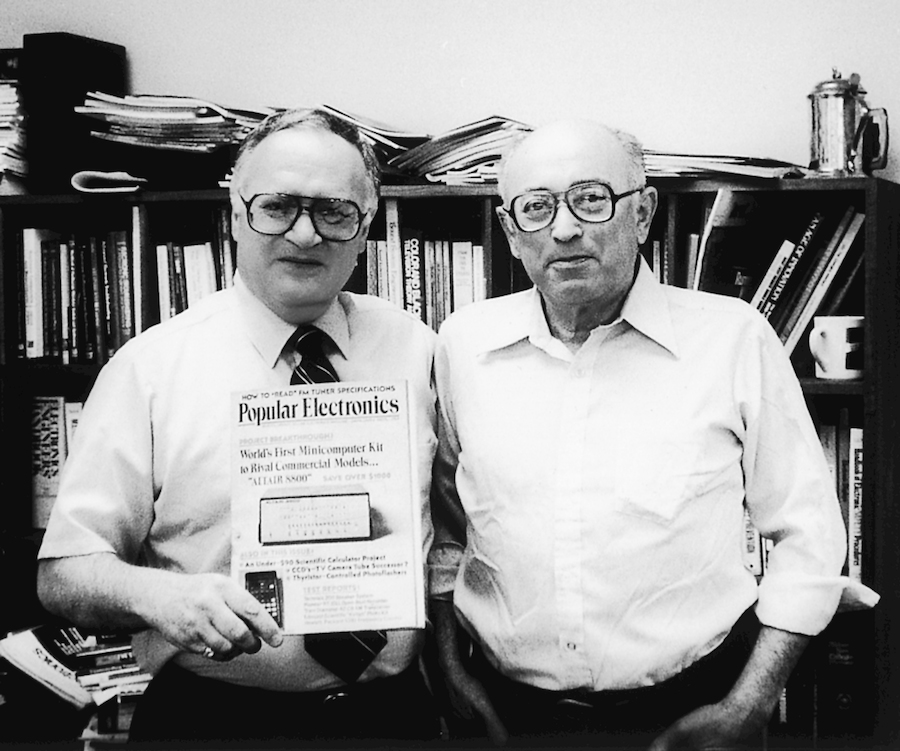

Figure 16. Art Salsberg and Les Solomon Salsberg, editorial director of Popular Electronics (left), and Les Solomon, its technical editor, pose with the historic January 1975 Altair cover.

(Courtesy of Paul Freiberger)

At the time Lancaster’s article was published, Popular Electronics technical editor Leslie (Les) Solomon was actively seeking a computer story for his magazine. Solomon and editorial director Arthur Salsberg wanted to publish a piece on building a computer at home. Neither of them knew if such a thing was even possible, but in their bones they felt that it should be. They didn’t realize that their competitor, Radio-Electronics, was already preparing to publish an article on just such a topic.

If a home-built computer design was possible, Solomon figured that it would most likely come from one of his “boys”—those young, technically sharp Popular Electronics contributors, like Stanford graduate students Harry Garland and Roger Melen, or Forrest Mims or Ed Roberts.

Designs were being submitted to Popular Electronics, but they weren’t from these stars, and Solomon and Salsberg found them unimpressive. Solomon described what he was seeing as “a rat’s nest of wires,” and Salsberg agreed: “They were terrible designs. They were tinker toys. They were kludges.” Solomon wanted to feature a really good design that he could develop into a groundbreaking story. So he encouraged his guys to send him their best designs, and they took his request seriously.

A colorful and ebullient editor with a wry New York wit, Les Solomon was known as Uncle Sol to his contributors. He developed a close relationship with them, carrying on lengthy telephone conversations and visiting their labs and workshops whenever he could. Solomon regaled his contributors with far-fetched stories and entertained them with magic tricks, most notably a stunt that involved levitating a stone table. Part of what made Uncle Sol fascinating was in trying to figure out what was for real and what was a complete put-on. But one thing was certain: he was serious about getting the best material for his magazine.

The avuncular Solomon was always willing to give his boys advice. When Garland and Melen submitted one of their designs, Solomon told them that they needed to find a distributor. He put them in touch with Ed Roberts, president of an Albuquerque-based company called MITS.

The Man Who Launched a Revolution

Solomon had met Roberts some time earlier. The Popular Electronics editor was vacationing with his wife in Albuquerque and stopped off to visit one of the magazine’s contributors, Forrest Mims. Mims took an immediate liking to Uncle Sol and brought him to meet his business partner, Ed Roberts. Solomon and Roberts also hit it off immediately. The meeting would prove to be a significant event in the development of the personal computer.

Roberts, like Solomon, enjoyed tinkering with electronics. He had played with electronics since his childhood in Miami and had managed to build a crude relay computer while still in his teens. Although he had originally wanted to become a doctor, Roberts decided to join the Air Force to get training in electronics. In 1968, while stationed in Albuquerque, Roberts, Mims, and two other Air Force officers started a small electronics company out of Roberts’s garage. They called their company Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems, or MITS, and sold radio transmitters for model airplanes by mail order.

Roberts soon involved MITS in other types of projects. For a time, MITS was building and selling a digital oscilloscope for engineers, but Roberts pushed to take on something more daring, closer to the technological cutting edge. His three partners objected to some of his wildest ideas, so he bought them out. By 1969 Roberts was alone at the helm, which was how he liked it.

A physically imposing man who became accustomed to giving orders while serving in the Air Force, Roberts ran a tight operation at MITS and would brook no nonsense from his employees. In every sense, MITS was Roberts’s company. By 1970, MITS had moved out of the garage and into a former restaurant whose name, The Enchanted Sandwich Shop, still hung over the door. Roberts began manufacturing calculators.

The calculator market was a dizzying place to be in the early 1970s. In 1969, when Intel got the contract to produce calculator chips for the Japanese firm Busicom, the cost to build and sell a calculator nearly approached the cost to build and sell a low-end minicomputer. By the early 1970s, semiconductor technology had changed the calculator market so radically that Ed Roberts could reasonably consider wrapping some electronics and a case around some chips from Intel and selling the results for a small fraction of the purchase price of a Busicom calculator.

What Roberts really wanted to do, though, was both more and less ambitious than building and selling conventional calculators: he was determined to produce programmable calculators and sell them unassembled in kit form. A calculator kit was the ideal product to be featured in the hobby electronics magazines, and Roberts made sure to publicize it there.

The calculator kits sold well for some time among enthusiasts, and Roberts made the fateful decision to invest the bulk of the MITS capital and development efforts in commercial handheld calculators. The decision turned out to be disastrously ill-timed.

Killed in the Calculator Market

Two trends in semiconductor technology reached critical stages in 1974 and helped to create the climate in which the microcomputer was born. The semiconductor companies began to produce and market applications of their technology—in particular, calculators—directly against Intel president Robert Noyce’s dictum that the chip manufacturers shouldn’t compete with their own customers. In addition, the early, crude microprocessor chips were being refined with better-thought-out designs and more power.

The first trend brought MITS to the brink of bankruptcy; the second yanked it back.

In the early 1970s, the semiconductor houses, racked by fierce technological and price wars, noticed that some of their customers had much healthier profits than they themselves did. One example was Commodore, a Canadian electronics company that had moved into Silicon Valley from Toronto and sold calculators that were assembled around a Texas Instruments (TI) chip. Commodore was raking in money from a product that was little more than a TI chip in a plastic case.

The demand for calculators seemed endless, and great profits were made in meeting the need. By 1972, TI had entered the calculator business, and other semiconductor manufacturers soon followed suit. “They just came in and ripped everybody to shreds,” according to semiconductor designer Chuck Peddle. TI’s attack on the industry was characteristically aggressive: it burst upon the market and immediately undercut everyone else’s prices.

Calculators quickly became smaller and more powerful, prices dropped dramatically, and profits shrank almost as fast. With a nationwide recession hobbling many businesses, 1974 was not a good year for the calculator industry. Peddle, who was working on microprocessor design at Motorola, recalled, “The market went to hell that year. Supply started catching up with demand. Everybody that year lost money in the calculator business.” Calculators went from being a high-end purchase to a sidewalk giveaway. The average price for a consumer calculator in 1974 was $26.25. A year before it had been $150.

One of the firms stricken by the recession and lackluster profits was MITS. In January 1974, MITS was selling a simple eight-function calculator kit for $99.95, and couldn’t bring the price any lower. Texas Instruments was offering a comparable, fully assembled calculator for less than half what MITS was asking. The tiny firm couldn’t swim in those waters. Ed Roberts lay awake nights trying to figure out where he had gone wrong.

The other pivotal development in semiconductors happened in April 1974, when the successor to the Intel 8008 microprocessor was completed.

Intel had really created the brain of a computer in the 8008. However, the 8008 was, in the words of Art Salsberg, “a kludge and a monster.” Everything was there, but not in the right places. It handled vital operations in a slow, roundabout way and demanded a contorted, awkward form of programming and design. Even engineers inside Intel disagreed about whether the 8008 could actually function as the brain of a viable, commercial computer.

The electronics hobbyists weren’t waiting for the semiconductor engineers to make up their minds.