______________

What Public-Sector Organizations Have Actually Done to Improve Engagement

As I’ve cited, many government jurisdictions and agencies have already taken action to collect data on, analyze, and improve employee engagement. While I have referred to examples of how agencies have acted on survey data, my emphasis has been on how these agencies have approached the process of surveying and acting on the results.

In this chapter, I highlight examples that focus on what these agencies have done in response to engagement data, including steps they’ve taken to improve the level of engagement. As I’ve noted, employee engagement is a hot topic. While the lion’s share of attention focuses on the private sector, there is also growing recognition in government that engagement matters. This attention is particularly timely for government organizations, which, as I described in Chapter 4, face unique challenges in improving engagement and also face pressure to do more with less. In government, the chief and sometimes only resource an agency has is its workforce. That’s why, in the public sector, success depends on a talented and fully engaged workforce.

What have public-sector agencies actually done to act on employee-engagement survey results, to maintain strengths and improve areas of weakness? The responses include a range of steps detailed throughout this chapter. This list of actions is not intended to be an exhaustive inventory of every action an agency can take to improve engagement. However, the list and the descriptions that follow highlight what individual government jurisdictions and agencies that have surveyed their employees have done to maintain or improve engagement. I’ve emphasized that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to improving employee engagement. However, I also think it’s useful to understand what public-sector organizations have done. The examples that follow can serve as a partial menu of proven approaches to improving employee engagement. The challenge for individual jurisdictions, agencies, and work units is to select the approaches, based on survey results and data analysis, that will support their mission, values, goals, and culture.

Here are some specific approaches that public-sector organizations have used to drive higher levels of employee engagement:

• Provide senior-level and enterprise-wide leadership on employee engagement.

• Improve agency communication.

• Build leadership and management competencies.

• Improve the management of employee performance.

• Ensure that employees believe that their opinions count.

• Create a more a positive work environment.

• Incorporate engagement into assessment of job applicants.

• Implement a new employee onboarding process.

• Help employees improve their well-being.

• Clarify the line of sight between employees’ work and the organization mission.

• Enhance employee prospects for career growth.

• Recognize employee contributions.

PROVIDE SENIOR-LEVEL AND ENTERPRISE-WIDE LEADERSHIP ON EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT

Virtually all analyses and lists of employee-engagement drivers conclude that leadership as critically important. For example, all the engagement dimensions identified by the U.S. Merit System Protection Board (MSPB) suggest that leaders can impact, negatively or positively, almost every aspect of employee engagement. (That’s in addition to the dimension specifically titled “satisfaction with leadership.”)

The leadership challenge in the public sector includes focusing on engagement despite the distinctive aspects of government, discussed in Chapter 4, that include frequent leadership changes, diffused decision making, and hard-to-measure goals. Part of the leadership solution to improve engagement is for senior-level and enterprise-wide leadership to make engagement an organizational priority and also model sound engagement practices. This includes explicitly integrating engagement into the strategic direction of the organization.

In both the United States and United Kingdom, the central HR departments in the national government have taken this to heart. The U.K. Civil Service annually conducts the People Survey of 500,000 civil servants. The U.K. Civil Service office instituted the national survey to replace more than 100 separate surveys previously conducted by individual agencies. The U.K. Civil Service also created a government-wide “employee engagement program team” in the prime minister’s cabinet. The team was charged with the following tasks:

• Provide a consistent set of measures for employee engagement across the entire U.K. Civil Service.

• Reduce the cost of engagement surveys across departments.

• Support government departments to successfully deliver the annual government-wide survey.

• Identify areas of employee-engagement best practices in the public and private sectors.

• Embed the concept and practice of proactive employee engagement across all levels of civil-service leadership and management.

• Encourage departments to focus on the four enablers of engagement that the U.K. Civil Service office identified:

1. Strong strategic narrative. Explain where the organization is going and why, which helps employees understand how their role contributes.

2. Engaging managers. Motivate, challenge, and support people, treating employees as individuals and seeking and responding to their views.

3. Effective employee voice. Ensure that employees in all areas are involved in decision making.

4. Organizational integrity. Align stated values and actual behaviors.1

The engagement team’s activities include encouraging U.K. agencies to integrate engagement into existing organizational strategies—that is, to help agencies view engagement as a key dimension of their strategies and make engagement business as usual and not just a program or an extra burden. The team has also matched organizations across government that face similar issues to help them support each other, share ideas and solutions, and avoid duplication of effort; developed “Civil Pages,” an online collaborative tool (described as the “the Facebook of the civil service”) that helps agencies share information and learn about best practices in engagement in civil service and other public- and private-sector organizations; and put on monthly engagement workshops to share best practices, enable agencies to share case studies, and provide examples from the wider public sector. These workshops include training on how to use engagement survey data, conduct enterprise-wide action planning, and create successful plans for fostering and communicating about employee engagement.

The U.K. Home Civil Service has also created a network of engagement practitioners that includes representatives from each government organization that participates in the People Survey. These practitioners take a lead role in using the survey results to drive improvements through communication and action planning. The network serves as a virtual team that tries to embed the principles of employee engagement across government departments as well as within them. Network members also provide feedback to the central employee-engagement team on the survey and data analysis and how to get the most value from the People Survey.

In the United States, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), the federal government’s central HR agency, administers, analyzes, and reports on the annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. OPM not only provides government-wide leadership on the survey but also strives to be a model employer, with a workforce of more than 5,000 employees. In the 2011 “Best Places to Work” rankings, OPM cracked the top 10 for the first time and maintained its place there again in 2012.

Improving engagement within OPM became a priority in 2009. At that time, the newly appointed OPM director, John Berry, made it clear to OPM senior executives and other leaders and supervisors across the agency that they would be held accountable for analyzing the OPM employee survey results and coming up with plans and strategies to address problem areas. Berry challenged his agency executives to be proactive and “drive change” by communicating, implementing workplace flexibilities, delivering training, and dealing with wellness issues.

One OPM strategy focused on improving the competencies of supervisors to help build employee trust. This commitment included the following:

• Targeting supervisory training to focus on specific competencies linked to the engagement survey results

• Creating supervisors’ forums to bring together leaders from across OPM to discuss common challenges

• Expanding performance-management training to improve communication with employees about performance expectations

Also in the U.S. federal government, the Department of Transportation registered the largest improvement in the 2012 “Best Places to Work” rankings for large agencies, repeating what it also accomplished in 2010. In 2009, the department was ranked last among large federal agencies. The agency’s improvement since then has been driven by department secretary Ray LaHood, who said, “When I found out that DOT was last I was stunned. I made a commitment that day to do everything I could to engage people and really change morale and opinions at the department.”2 LaHood made a personal commitment to improving the agency’s score, using the ratings as a tool for change.

This philosophy was communicated through listening sessions and in emails from the secretary and other Department of Transportation senior leaders. Most importantly, the changes resulting from employee feedback have been communicated to frontline employees.

After improving its “Best Places to Work” score by 8.2 points in 2010, the department added its own agency-specific questions to the OPM survey. From those questions, the agency realized that employees wanted to improve work processes. The secretary then asked senior leaders to let employees know that management heard this message and also encourage more feedback. The secretary’s office then solicited input from each operating unit and made changes to meet employee needs.

In local government, the city of Minneapolis and Oregon Metro Government both have made the commitment to employee engagement that includes incorporating engagement into strategic goals and then acting to achieve these goals. In Minneapolis, the strategic goal (“A city that works”) includes “city employees are high-performing, empowered, and engaged.”3 This focus on engagement also starts at the top with Mayor R. T. Rybak. He reviews survey results himself and meets with department heads. If there are areas where a department can improve, Rybak will discuss with department leaders. Oregon Metro’s commitment to engagement includes the following:

• The HR department’s vision is defined as “increase level of employee engagement in order to maintain a productive workforce to meet agency mission.”

• In its list of employee values, Metro encourages “teamwork—we engage others in ways that foster respect and trust.”

• A strategic goal in the HR department’s five-year plan is to “create a great workplace with diverse, engaged, productive, and well-trained employees.”4

Driving Improved Engagement Through Strong Leadership at the Chorley Borough Council

Chorley Borough is a public-sector jurisdiction in the United Kingdom, akin to a U.S. county government. In 2006, Donna Hall took over as council chief executive, bringing a different style of leadership, including focusing on the customer. In 2008, the council was rated as excellent by the national government Audit Commission and was ranked number 2 and named “best improver” in The Times’ list of “Best Councils to Work For.”5

Hall communicated a “customer first” vision. Her changes included “listening days” every six to eight weeks that run for 60 to 90 minutes, where all staff contributed ideas; “back-to-the-floor exercises” to keep managers in touch with staff and residents; a well-being program; and a focus on reducing sickness absence.

According to Hall,

I don’t have the monopoly on good ideas. The people who do the job are now being asked and because we’re a small council we need everyone to play their part. We simply needed to remind ourselves what we are here to do—serve the public—and put that at the heart of the way we work.6

IMPROVE COMMUNICATION ABOUT ENGAGEMENT, THE ORGANIZATION, AND THE WORKPLACE

Communication is the glue that holds employee-engagement initiatives together and is particularly critical for government. As discussed in Chapter 4, public-sector organizations face engagement challenges that include persistent attacks on government, hard-to-measure goals, complex decision making, and frequent leadership changes. Effective communication can help overcome these obstacles to improved engagement

Public-sector organizations must communicate throughout the entire cycle of planning, conducting, and acting on engagement surveys. In addition, however, agencies have learned through their engagement surveys that they need to improve communication in general. Communication helps put employees in the best position to perform well—one of the key drivers of engagement.

In the city of Juneau, the survey results showed that a department leader wasn’t clearly communicating his vision to department employees. In response, HR facilitated a series of structured meetings between the director and key department supervisors. The result was a dramatic increase in this department’s engagement scores in the next survey. According to Mila Cosgrove, the Juneau HR director, communication in this department (and in the entire city) requires managers to “look every employee in the eye and tell them they’re part of the solution.”

Oregon Metro learned from its engagement survey data that employees wanted more—and more accurate information. The survey data also showed that managers were “removed from their employees.” In addition, first-line supervisors were not viewing themselves as management but instead as labor-union allies. Metro also realized that simply asking managers to communicate more or better was not the real solution. Managers had to be equipped with the information they needed to communicate effectively.

The solution was “intentional communication,” an approach to push information to employees by engaging first-line supervisors. The goals were to deliver accurate information to employees in a timely manner and also strengthen first-line supervisors’ connections to management.

Metro started by developing a more purposeful way to communicate about the organization’s budget—a critical area of concern for employees. Metro began this process with an all-managers meeting where managers were encouraged to ask questions about the status of the budget. These answers were then converted into talking points, and managers were asked to share this information in conversations with their staff. This approach departed from the usual practice of discussing a topic with the senior leadership team and then assuming that leaders would communicate down and across the organization. Instead of this hit-or-miss approach, Metro’s intentional communication approach organized both the message and the way it was communicated. After developing the budget talking points, Metro applied this tactic to other issues its employees said were important.

In the federal government, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) faced enormous pressures and increased workloads stemming from the 2008 financial crisis. FDIC rose to the top of the “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” rankings (after being near the bottom) in part because of improved internal communication with employees. This included creating an internal ombudsman position, reporting directly to the FDIC chairperson, to handle employee problems and grievances. FDIC also launched an internal website for employees to submit questions and get answers on workplace issues and held town-hall meetings and conference calls with the chairman that enabled all employees to have their questions answered and also provide direct input to FDIC leaders.

FDIC also created a “cultural-change council” that included employees from all divisions and levels. Council members were charged with developing ideas to better communicate with, and empower, employees. This council served as conduit for employees to generate ideas. The FDIC “director of cultural change” said that a key emphasis has been to demonstrate to employees that management “values their opinions and that their voices are being heard.”

The Federal Aviation Administration: “From Worst to First”

The leadership of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was not pleased when the 2009 “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” rankings placed FAA third from the bottom for agency subcomponents. (FAA is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation.) The response to this low ranking was a concerted effort to improve workplace conditions, resulting in the FAA boosting its score by 19.2 percent in the 2010 rankings. Again in 2012, FAA was one of the most improved federal agencies.

The improvement began when the FAA administrator adopted the slogan “worst to first” and formed a steering committee that focused on employee engagement. The administrator held regular brown-bag lunches and town-hall meetings with employees to encourage them to voice concerns. Agency leaders made a commitment to get back to employees and answer questions they could not answer immediately.

Senior FAA leaders also became more involved in helping newly hired employees adjust to the workplace and also placed a new focus on providing positive feedback and better professional development opportunities.

FAA launched IdeaHub, a website that received 500 suggestions for improvement from FAA employees in just its first week and was eventually expanded to serve the entire Department of Transportation. Even the small step of instituting agencywide casual Fridays helped improve satisfaction and engagement.

Another creative solution was creating a “Making the Difference” award, presented by the administrator each January to an agency employee who made an important contribution to improving employee engagement.

The University of Wisconsin Hospital also made communication a priority. For example, the hospital launched an online “Best-in-Class Library of Action Steps” to communicate and publicize (and replicate, the hospital hopes) the good ideas implemented by units as the result of employee-engagement surveys. The library, which the HR department continually updates and makes available to all employees through the hospital intranet, lists and describes specific activities units have designed and implemented in categories such as communication, recognition and rewards, involvement and belonging, growth and development, future vision, trust, performance excellence, and diversity.

Other initiatives to improve communication in government driven by employee satisfaction/engagement survey data include the following:

• The Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA), after being ranked last in “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government,” began publishing a weekly newsletter that covered important information about mission performance. The publication included updates on legislation, meetings, and budget information. The FLRA chairwoman also held all-employee town meetings that used videoconferencing to involve employees outside the headquarters.

• The state of Washington’s Information Services System Division responded to employee survey results by establishing the expectation that each manager/supervisor should have routine (i.e., at least monthly) one-on-one and unit staff meetings to promote communication within and between units and give priority to sharing conversations from management discussions.

• The director of the federal OPM implemented several new ways to communicate in response to low “Best Places” scores. His initiatives included conducting “free-flowing” monthly town-hall meetings to solicit employee feedback and implementing “IdeaFactory,” where workers are encouraged to submit innovative ideas for workplace improvements.

• At the British Department of Work and Pensions (DWP), once a year all DWP senior managers are asked to participate in “back to the floor,” where they spend a week working with staff who directly serve customers. More than 200 senior managers did this in 2009–10. This frontline experience provided leaders with ideas on what works well for delivering customer service and allowed employees to speak directly with managers about service improvements. One department secretary personally went back to the floor four years running and then shared his experiences through a published personal diary. Employees reported that it was valuable to see senior colleagues experiencing their world firsthand.7

• A U.S. regulatory agency, the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC), was one of the most improved agencies in the 2009 “Best Places in the Federal Government” rankings in part because of enhanced internal communications. Specifically, the FMC opened meetings of the full commission to all employees and encouraged them to attend to improve their understanding of how important decisions are made by FMC management and the five commission members. The commission also sought to better educate staff about issues in the industry they regulate by inviting representatives from the maritime industry to speak directly with staff. Unfortunately for FMC, its engagement momentum stalled, and it plummeted in the 2012 rankings.

• At an air force civilian unit, engagement survey data and follow-up discussions revealed that employees were frustrated with some meetings that were being held in a long hallway. This was not only uncomfortable; it was also inefficient. The simple solution was to move the meeting to a conference room. The lesson here is to never underestimate the value of taking small steps.

BUILD MANAGERIAL AND LEADERSHIP COMPETENCE TO IMPROVE ENGAGEMENT

As the U.S. OPM does, other government agencies that have focused on assessing and then improving engagement understand the connection between strong leadership and employee engagement. These organizations have taken action to build and upgrade leadership competence, which underlies virtually every driver of employee engagement.

The Air Force Materiel Command, which conducted the Gallup Q12 engagement survey, has made its supervisory staff a critical part of its engagement strategy. In analyzing its survey results, the command realized that when supervisors are engaged, their employees are also more likely to be engaged. The survey results helped the command understand where supervisory training had been successful and where it needed to focus more on the needs of supervisors. In response, the command developed and implemented a more robust training and development program for managers and supervisors.

The results have been encouraging—employee turnover has decreased, particularly for newly hired staff: use of sick leave and workplace accidents are down; the ratio of engaged to disengaged employees is up; and according to Minnott Gaillard of the command, “Engagement is becoming a mindset, not just a buzzword.”

The California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Communication Programs Division conducts biennial employee satisfaction surveys. In response to the survey results, the DMV collaborated with the University of California—Davis on a leadership development program that focuses on the different levels of management and includes a component on empowering employees, management styles, and how styles need to align with employees.

According to Oregon Metro, one of the core management competencies involves fostering employee engagement. Metro has linked training and development programs to these competencies, including engagement.

In the United Kingdom, the city of Sussex’s police force, which conducts employee surveys, has developed a leadership-capability framework to describe the types of leaders the force needs and also help ensure that leaders behave in ways that reflect the force’s stated values. The framework includes components such as “moving from checker to coach,” “putting we before me,” and “standing in the shoes of the public,” to clearly communicate what the police force means by leadership. A new leadership-development program based on these values, for leaders at all levels, is being rolled out. According to the force’s HR director, it will take time to change the management culture because many officers still expect HR to “do the people-management bit.” Police-force leaders recognize that too many sergeants and inspectors and even some chief inspectors still seem to think they are one of the team; they don’t really accept that they are managers. The force’s next step is to ensure that the new leadership-capability framework is incorporated into how staff are recruited and assessed for management positions and how they are appraised and developed.8

In the U.S. federal government, FDIC focused on leadership by creating a set of core values that directly relate to engagement: integrity, teamwork, accountability, fairness, and effectiveness. The FDIC chair (the corporation’s chief executive) and other top FDIC leaders then delivered clear and repeated messages that they were dedicated to creating a high-functioning workforce and improving workplace conditions. The result was ascension to the number one spot in the 2011 and 2012 “Best Places” rankings.

In Canada, the province of Alberta’s response to engagement survey results included making senior executives accountable for improving employee engagement by including engagement as an element in the executives’ performance goals/contracts.

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) Federal Technology Service (FTS) southwest region, which serves civilian and military agencies and the Native American community, administered the Gallup Q12 engagement survey. FTS acted on the survey results in several ways, including by incorporating the Q12 questions into an outline for supervisors to use in their performance appraisal discussions with subordinates. According to the GSA regional administrator, “We discussed the (survey) results during staff meetings, during associate meetings, and any other opportunity we had. Each group developed action plans. We discussed these actions during our leadership sessions. Managers discussed these action plans during meetings with their associates.”

As a result, FTS engagement scores increased by 10 percent overall, with one FTS group raising its score by 90 percent. The overall engagement scores for the southwest region were in the 99th percentile in the Gallup database. According to Gallup, this is world-class engagement.9

Improved employee engagement in FTS also improved customer-satisfaction scores—a key metric. The region’s goal is at least an average 4.0 rating (on a 5-point scale) on customer satisfaction surveys. Actual satisfaction scores were about 4.8. In addition, although FTS’s business volume increased by more than 112 percent, operating costs only increased by 4 percent.10

Leadership Competencies: The Office of Personnel Management

In the U.S. federal government, OPM has developed five executive core qualifications, which embody the competencies senior leaders are expected to master and demonstrate. Each of the five competencies includes a set of specific behaviors, many of which link to employee engagement:

1. Leading change. Bring about strategic change, both within and outside the organization, to meet organizational goals. Inherent is the ability to establish an organizational vision and to implement it in a continuously changing environment. This competency includes these specific behaviors:

• Creativity and innovation

• External awareness

• Flexibility

• Resilience

• Strategic thinking

• Vision

2. Leading people. Lead people toward meeting the organization’s vision, mission, and goals. Inherent is the ability to provide an inclusive workplace that fosters the development of others, facilitates cooperation and teamwork, and supports constructive resolution of conflicts:

• Conflict management

• Leveraging diversity

• Developing others

• Team building

3. Results driven. Meet organizational goals and customer expectations. Inherent is the ability to make decisions that produce high-quality results by applying technical knowledge, analyzing problems, and calculating risks:

• Accountability

• Customer service

• Entrepreneurship

• Problem solving

• Technical credibility

4. Business acumen. Manage human, financial, and information resources strategically:

• Financial management

• Human-capital management

• Technology management

5. Building coalitions. Build coalitions internally and with other agencies, state and local governments, nonprofit and private-sector organizations, foreign governments, or international organizations to achieve common goals:

• Partnering

• Political savvy

• Influencing/negotiating11

DRIVE ENGAGEMENT THROUGH IMPROVED MANAGEMENT OF EMPLOYEE PERFORMANCE

To be fully engaged, employees need to understand what their roles, responsibilities, and expectations are and receive feedback on their performance. In the world of HR, this is known as performance management and is fundamental to the driver that the MSPB identified as the “opportunity to perform well at work.”

Performance management is especially critical to employee engagement in government because, as described in Chapter 4, managers are constrained by frequent leadership changes, complicated decision making, hard-to-measure goals, and restrictive civil-service rules, and they also lack the financial incentives that private-sector managers have.

What Is Performance Management?

The University of Wisconsin has defined performance management as follows: “A continual process of establishing relevant and reasonable expectations, measuring outcomes, and providing appropriate follow through in the form of coaching, training, rewarding, and taking corrective action and/or discipline. A primary purpose of performance management is to create a climate and environment for employee development and success.”

Employee-engagement research conducted by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board has revealed the power of effective performance-management practices to improve employee engagement. The board compared the practices of the four federal agencies with the highest levels of employee engagement to the four bottom-scoring agencies. The most significant factor that differentiated the high-engagement agencies from the low-engagement agencies was effective performance-management practices. According to the MSPB report, “Every positive performance-management practice we reviewed (e.g., senior leaders communicating openly and honestly with employees, employees having written performance goals) is employed more widely in high engagement agencies than in low engagement agencies.” Based on these findings, MSPB made a series of recommendations to executives, managers, and supervisors to ensure that performance-management practices drive high employee engagement (see box).12

U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board Recommendations for Effective Performance Management

For All Leaders (Executives, Managers, and Supervisors)

• Hire with care and use the probationary period as part of the selection process, particularly in government. The best way to avoid performance problems is to hire candidates who have high potential for success. Provide job applicants with an accurate job description and a realistic preview of the pros and cons of the position. Use a multiple-hurdle approach in which only the best qualified candidates move on to the next step in the selection process. Use the probationary period as the final step in the selection process, and remove employees who do not perform well.

• Develop a strong working relationship with each employee by talking informally and frequently (e.g., two or three times per week). Get to know employees as people, provide informal feedback, and learn about individuals’ concerns and goals.

• Meet regularly with each employee to review progress and provide feedback. Schedule regular meetings (at least monthly) with each employee to discuss progress and any obstacles to success, provide feedback and recognition, explain new assignments, communicate high performance expectations, provide information about the work unit or organization, respond to questions or concerns, and review progress on development plans.

• Model how to request and use feedback. Set an example by requesting feedback on your performance as a supervisor and by sharing feedback you receive from your manager. Discuss with employees how you plan to use the feedback you receive.

• Conduct annual or semiannual assessments of each employee’s strengths and development needs. Provide development opportunities for all employees, including both specific training needed for the current job and broader skill development.

• Manage poor performance promptly and assertively. Hold all employees accountable for their performance:

• Provide recognition and other positive consequences for good work.

• Take prompt corrective action when employees are not performing well, making it clear that continuing poor performance will not be tolerated and following up with consequences if the poor performance continues.

• Avoid transferring poor performers’ work (or the poor performers themselves) to other units.

For Managers and Executives in Particular

• Involve employees in building a high-performance organization. Use the results of agency engagement surveys, plus additional employee input, to identify organizational strengths and weaknesses. Work with employees to create and implement an action plan to build a high-performing organization.

• Build employee trust and confidence through frequent, open communication. Invest effort in gaining the respect and trust of your employees by openly sharing information about the organization, both positive and negative; aligning words and actions; and making it safe for employees to express their perspectives. Develop personal connections with employees through meetings, visits to work sites, exchanges of ideas, and other forms of in-person communication.

• Engage new employees and nurture your investment in new employees by providing a yearlong onboarding program.

• Develop and communicate with employees about a recognition program that tightly links recognition to performance. Use pay raises as a recognition tool, giving raises only to employees who are performing at “fully successful” or better levels. Let employees know they are receiving the increases because of their successful performance. Develop nonmonetary recognition practices.

• Select supervisors who will effectively manage performance and then hold them accountable for effective performance management. Make it clear that they are personally responsible for effectively managing their employees’ performance to produce results. Regularly review management strategies with each supervisor.

• Provide supervisors with the support they need to successfully manage their work groups, including training, resources, and support. In particular, remove organizational obstacles to taking action against poor performers, and back supervisors up when they do this.

• Evaluate the effectiveness of the agency’s current performance appraisal system. Assess how it contributes to or detracts from accountability, communication, and recognition of good performers. Involve employees and solicit their ideas for alternative approaches.

ENSURE THAT EMPLOYEES BELIEVE THEIR OPINIONS COUNT

As described in Chapter 4, decision making in government is often influenced by outside events and actors, including political forces, that can make decisions seem irrational. This is at odds not only with engagement drivers (“my opinion counts”) but also with the public-service motivation that attracts many public servants to government. In response, agencies striving to improve engagement have reached out to their employees to involve them more directly in decision making.

In the previous section on communication, I wrote about ways in which agencies have communicated the rationales for their organizational decisions. Agencies have also implemented approaches to solicit opinions and innovative ideas from employees and then adopt the best ones.

One example is the IdeaFactory at the U.S. Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in the Department of Homeland Security. TSA has a difficult mission that requires its employees to strike the difficult balance between airport security and customer service. TSA therefore also has a particularly tough employee-engagement challenge. It is a large agency, with its 60,000+ employees scattered across more than 450 airports not only in the continental United States but also in remote locations in Alaska and places like Pago Pago and Guam. In addition to this workforce challenge, TSA employees are also regularly criticized by the public, the media, and politicians. Not surprisingly, TSA is a high-turnover organization for government, with annual attrition among screeners as high as 20 percent.

It’s not a huge surprise, therefore, that TSA has been near the bottom of the federal “Best Places” rankings, but it has improved since it was first ranked in 2005. One approach to improve engagement by soliciting employee opinions is the IdeaFactory, dubbed a “21stcentury suggestion box.” IdeaFactory is an online system similar to a blog that applies a social-media approach to create an online community that gathers and shares employee suggestions. This program, created after an employee survey revealed that TSA employees believed their voices were not being heard by the agency’s leaders, sets out three main goals, all directly or indirectly linked to employee engagement:

1. Engage employees and ensure that every member of the large and dispersed TSA workforce has a voice in the way the agency and its operations evolve.

2. Collect constant, fresh input and perspectives on improvements to keep the agency flexible and effectively mitigate security threats.

3. Disseminate information about new and existing programs, initiatives, and policies to frontline employees and provide a forum for communication.

Employees post their ideas online, and then other employees rate and comment on the posted ideas. In this way, employees communicate with agency leaders, TSA offices, and each other. These employee ratings for each idea are also posted. The IdeaFactory team reads each idea and evaluates those that are popular or that fit especially well with specific strategic agency goals. Senior leaders and program managers react to the posted ideas by debunking myths and responding to suggestions, including explaining why some suggestions are not going to be implemented.

Ideas that receive the most support from other employees may ultimately be implemented across the agency. Winning ideas net the suggesting employees a trip to TSA headquarters to help implement their ideas. Employees who submit accepted ideas are rewarded with a certificate of recognition and a TSA coin, which is highly valued across the agency.

IdeaFactory suggestions that have been implemented range from small procedural changes in baggage inspection to more strategic approaches, such as establishing separate family and road-warrior passenger lanes. Other implemented ideas include the following:

• A nationwide employee referral bonus program to help recruit transportation security officers

• A job-swap website that allows officers to post their interest in swapping job locations

• “Mourning bands” that allow officers to place special markings on their badges to recognize employees who have passed away

• Clarifying on the TSA public website that the “children” listed as being allowed to bring liquids through the checkpoint actually means “infants/toddlers”

• Updated training programs based on employee suggestions

In its first two years, more than 25,000 employees visited the IdeaFactory site and posted almost 9,000 ideas. This led to the implementation of 85 innovative ideas.

The FAA also implemented a similar online program, “IdeaHub.” In its first year, IdeaHub engaged 25 percent of the FAA workforce, generated more than 4,000 ideas, and received 55,000 ratings on these ideas plus more than 12,500 employee comments. FAA officials point to this innovation as one reason employee satisfaction improved by 19 percent in the 2010 “Best Places” rankings.

The National Health Service “Engagement Tool Kit”

The publicly funded National Health Service (NHS) in Great Britain takes engagement seriously. The service has produced a 75-page engagement tool kit that includes “practical advice for increasing staff engagement” as well as links to other resources. The tool kit covers the following:

• Benefits of engagement

• Business case for engagement

• Financial benefits

• The staff engagement star (employee-engagement model)

• Top tips on improving engagement

• What to include in the engagement strategy

• Tool for continuous assessment of engagement

• Communicating and involving staff

• Advice for line managers

• Tips for induction (onboarding) to support engagement

• Using NHS staff survey scores13

CREATE A POSITIVE WORK ENVIRONMENT

Public-sector organizations that have measured employee satisfaction/engagement and then acted on the results have also taken specific steps to create more positive work environments, including helping their employees balance their work and personal lives. Given what I described in Chapter 4 about the challenges that government jurisdictions and agencies face as they attempt to improve employee engagement—including attacks on government, frequent leadership changes, influence of external forces on decisions, and limited financial tools to influence behavior—creating a positive work environment is critical.

As discussed previously, effective performance management by supervisors is fundamental to creating a positive work environment. In addition, so is implementing more flexible work arrangements.

In the Partnership for Public Service report, “On Demand Government: Deploying Flexibilities to Ensure Service Continuity,” we documented that flexible work arrangements (e.g., compressed work weeks, flextime, part-time work, job sharing, and telework) were underutilized in the federal government. The Partnership found that many managers resist adopting flexibilities because they view them primarily as employee perks. In state and local governments, a key flexibility—telework—is also underutilized for essentially the same reason.14

This attitude ignores research that has proven the value of workplace flexibilities. Benefits include expanding service hours and reducing costs through downsized physical office space, fewer staff relocations, reduced employee travel, and expanded use of online training. Workplace flexibility also enables agencies to maintain operations during times when facilities are closed unexpectedly.

Ironically, even agencies that have not implemented flexibilities like telework report that they believe that increased use of flexibilities will improve employee satisfaction and engagement and allow agencies to better adapt to changing workforce expectations.15 For example, in the federal government, employees who telework scored seven percentage points higher on the 2012 federal government engagement scale (based on the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey) than employees who did not telework.

During the historic series of major snowstorms that pounded the Washington, DC, area in 2010 (“snowmaggedon”), the federal government was officially closed for almost a week. However, several agencies continued operating via telework. The Patent and Trademark Office, for example, reported that about 4,400 of its patent examiners, trademark attorneys, and other employees—about 46 percent of PTO staff in the DC suburbs of northern Virginia—teleworked even though the federal government was officially closed. About 30 percent of the employees in the U.S. GSA and OPM also teleworked during the storms.16

Other federal agencies also understand the need to implement workplace flexibilities, often in response to employee survey results. In addition to the Patent and Trademark Office (a federal leader in the percentage of employees who telework in general, not just during snowstorms) and OPM, the Government Accountability Office (which consistently ranks high in “Best Places”) has adopted “flexiplace” and telecommuting to help employees better balance the demands of work and home. The GSA has made a commitment to accelerate the pace of telework for federal government employees and is leading by example. According to GSA, its telework activities have helped reduce highway traffic congestion and associated vehicle emissions. GSA’s senior leadership actively communicates the value of telecommuting, advocating for the technology needed to support a mobile workforce. GSA also launched mandatory training to educate employees on the changing culture at GSA and emphasize the benefits of telework—that is, to help employees find greater balance between their work and personal lives.

At another agency, the FAA, even the small step of instituting agencywide casual Fridays helped create a more positive work environment that improved employee satisfaction.

Despite these examples, the Partnership for Public Service’s “On Demand Government” reported that one of the major barriers to greater use of workplace flexibilities is resistance by managers who said they need to see their employees face to face to make sure they are actually being productive. As pointed out in the report, however, managers who can only be sure that their employees are working by seeing them sitting at their desks are not doing their own jobs; they should have other ways to “measure” productivity.17

The city leadership in Minneapolis, which has been conducting engagement surveys since 2004, understands the value of flexible work arrangements. In the city’s 2009 survey, 71 percent of employees who responded agreed that having flexible work arrangements was important to them. In 2010, in response to these results, the city council approved an alternative work arrangement policy.

This new policy was designed specifically to “increase employee commitment, engagement, morale and productivity” and includes the following alternative work arrangements:

• Compressed workweeks. Full-time employees work 40 hours each week (or 80 hours every 2 weeks) but have the flexibility to work fewer than 5 (or 10) days (e.g., they can work four 10-hour days).

• Flextime. Employees can deviate from standard starting and ending times.

• Job sharing. More than one employee can share the work of one full-time budgeted position.

• Gradual retirement. Employees nearing retirement can modify their schedules to retire gradually instead of transitioning from full time to fully retired overnight.

• Telework. Employees can work remotely, from their homes, mobile worksites, customer sites, or other locations.

Although not all alternative arrangements are right for all positions (or employees), the city HR department believed it was important to provide departments with a set of work flexibility policies and tools. Since Minneapolis has a heavily unionized workforce, HR has also worked with unions and city departments to expand coverage to bargaining units interested in extending coverage to their members. Several have done so.

City of Minneapolis

Alternative Work Arrangement Agreement for Telework

Employee name__________________________________

Employee ID__________________________________

Department/division__________________________________

Employee home address (include city and state)__________________________________

Home or cell phone number__________________________________

Remote work location (specify home or other)__________________________________

Schedule Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday (in city office)__________________________________

I (employee), have read, understand, and agree to adhere to the city of Minneapolis AWA policy, the AWA procedures, my department’s telework procedures, and the terms as described in this agreement. I will request any deviation from the approved AWA as soon as possible with my supervisor. Special circumstances (special division rules, conditions, etc.) are listed separately in an attachment to this agreement. I have discussed the telework agreement, including scheduling days and hours of work, communications, employee/supervisory responsibility for work progress and monitoring work, the use of the city’s equipment, data security, and data privacy with my supervisor. Tele-workers are responsible for damage to city-owned equipment and for filing a police report with their local police department for stolen city-owned equipment. I understand that I must notify my supervisor in the event of any damage to or loss of city property. I understand that I need to have proper insurance coverage in place at the remote work location. I understand that either the city or I may terminate the telework agreement with reasonable notice to the other party. Upon termination, I will return all city-owned equipment to the city immediately or facilitate the city’s access to such equipment for retrieval. (Note: Additional sheets may be attached to this agreement to document other important aspects of the AWA.)

Other Important Information

Employee signature__________________________________Date__________________________________

For the City

Supervisor signature__________________________________Date__________________________________

Department head or designee signature__________________________________Date__________________________________

INCORPORATE EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INTO ASSESSMENTS OF JOB CANDIDATES

Engaged employees are made, not born, but one innovative way to “bake in” engagement is how the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID) incorporates engagement into how it assesses candidates for senior civil-service positions. The DFID candidate evaluation process includes a session during which candidates interact with a group of staff from across the department. The candidates are asked to analyze a set of U.K. Civil Service People Survey engagement-survey results to identify key issues and then discuss their ideas about how to deal with these issues. This discussion assesses each candidate’s ability to do the following:

• Engage with staff in analyzing issues and developing responses.

• Weigh the costs, benefits, and impact of possible solutions.

• Apply knowledge of how to manage people.

• Gain commitment for the proposed actions.

• Reflect upon his or her own behavior and evaluate its impact.

Each candidate’s performance is scored along with other job dimensions to determine if he or she has the leadership competence needed for senior civil-service positions. All candidates receive feedback on their performance in the selection process. DFID management believes that this exercise has helped identify well-qualified candidates who have strong engagement, management, and leadership skills. The process shows DFID’s commitment to engagement as well as using People Survey results to improve the department.18

Incorporating engagement into job candidate assessment doesn’t have to be limited only to leadership positions. Research by the consulting firm Development Dimensions International (DDI) on almost 4,000 employees in a variety of jobs has revealed six personal characteristics that predict the likelihood of becoming an engaged employee:

• Adaptability

• Passion for work

• Positive disposition

• Self-efficacy

• Achievement orientation

Job applicant questionnaires, sometimes referred to as “career batteries,” can help hiring organizations, and managers identify candidates with these characteristics who therefore have the highest probability of performing effectively, while also being satisfied and engaged. The questionnaires cover how candidates would handle certain situations and how they would rate the effectiveness of various actions to achieve goals. These tools can be particularly useful in public-sector agencies, given the importance of identifying candidates who have the public-service motivation that is critical to success in government.19

IMPLEMENT A NEW EMPLOYEE ONBOARDING PROCESS

The following anecdote appeared in “Getting Onboard: A Model for Integrating and Engaging New Employees,” a Partnership for Public Service report:

Two dollars and 85 cents. That’s what a new government employee found in his desk when he reported for his first day of work. We know this because this civil servant showed up for his first day with no computer and nothing better to do than count the loose change and throw away the chewing gum wrappers he also found in his desk. Maybe the $2.85 was his hiring bonus.20

In “Getting Onboard,” we catalogued the often sad state of onboarding new employees in the federal government. More important, we laid out a comprehensive model for how government can ensure that new employees are onboarded effectively. This is critical because effective onboarding and employee engagement are directly related.

Most of us have our stories of reporting for a new job when we were ready for the job but the job wasn’t ready for us. My personal “favorite” is when my family and I, including our two young daughters, moved halfway across the country for a job in Wisconsin state government. When I arrived for my first day at work, eager to get started, I was greeted with the news that our family wouldn’t be eligible for employer-paid health insurance until I had worked there for six months. That definitely took the edge off my excitement about the new job—and also made for a tough conversation at home that night.

As emphasized in “Getting Onboard,” perhaps no aspect of human-resources management has been more overlooked by government than onboarding—integrating new employees into their agency work environments and equipping them to become successful, productive, and engaged.

Onboarding is particularly critical in government for at least two reasons. First, as we noted in Chapter 4, strong civil-service requirements can make hiring in government slow and laborious. Therefore, agencies should be especially committed to making sure that new hires get off to a good start and don’t quickly become disillusioned and leave. There’s no excuse for wasting the time, money, and effort spent on recruiting and hiring by following it up with an ineffectual onboarding process.

Second, as noted earlier, it is unfailingly difficult to remove poor performers in government after they pass probation. Poor performers who pass probation therefore become the “gift” that keeps on giving. It’s critical to weed out poor fits during the onboarding process.

Good onboarding is not just the right thing to do; it also pays dividends. Research by the consulting firm Hewitt Associates revealed that organizations that invest the most time and resources on onboarding are rewarded with high levels of employee engagement. The Recruiting Roundtable found that effective onboarding can improve employee performance by up to 11.3 percent.21

Despite this evidence, the Partnership’s research on onboarding in government revealed that newly hired public servants often have disappointing experiences on their new jobs. Here are more quotes from focus groups with brand-new federal employees:

• “My first week was terrible. I didn’t have any equipment, I wasn’t given any assignments, there was nothing on my desk, and my supervisor did not even come see me for the first three days I was there.”

• “When I showed up for work on my first day, my manager had no idea I was coming. Apparently HR had not informed her of my start date.”

• “I was sent to a conference room where someone from HR helped me complete a bunch of forms. I was not introduced to anyone, I had no one to go to lunch with, and no one had set up my computer access so I sat there and stared at the wall. By the end of the day, I felt I had made a terrible mistake in leaving my old job.”

• “I couldn’t receive my ID on the first day so it was hard for me to go anywhere and my manager did not give me any work to do … my manager was not very welcoming. By the end of the day, I was terrified that I had left a great job for this.”22

In many cases, problems like these result from small, easily avoidable mistakes. While minor, these mishaps can have a major impact on a new employee’s view of government, as well as his or her level of engagement. After all, you only get one chance to make a first impression.

To address this often underappreciated issue in government, the Partnership for Public Service, in cooperation with Booz Allen Hamilton, developed a comprehensive model for strategic onboarding designed specifically for government, although it can also be applied in other sectors too. The model has been adopted by public-sector organizations, including the University of Wisconsin.

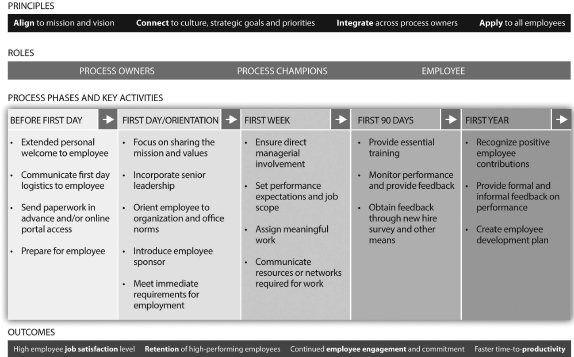

The model onboarding process starts with a set of onboarding principles:

• Align onboarding to agency mission and vision.

• Connect to culture, strategic goals, and priorities.

• Integrate across process owners (e.g., HR, information technology, new hire’s supervisor).

• Apply to all employees (i.e., in all jobs, at all levels, and at all locations).

As shown in Figure 12.1, the onboarding process itself has five phases, beginning when the new employee accepts the job offer and continuing through the entire first year of employment. The five phases vary in length but represent critical steps during the new employee’s first year.

The five steps are as follows:

1. Before the first day. Good onboarding begins when a new hire accepts the job offer, not just when he or she shows up on the first day. This first phase of onboarding occurs after the employee accepts the job but before his or her first day of employment. During this time, HR staff notify other key “process owners” such as IT (to make sure the new employee has a working computer as well as a valid ID and password) and space management (to set up a work station); send hiring and benefits paperwork to the new hire (so he or she doesn’t have to waste time completing these forms on the very first day—a surefire way to dampen enthusiasm for the new job); and communicate logistical information. This is also when a “peer partner” should be designated to help the new employee become adjusted to the agency’s norms and culture.

2. The first day. The second phase, first day/orientation, occurs when the new employee reports to work and continues with orientation activities in the first few days. Formal orientation is critical because it’s usually the first substantive encounter a new employee has with the agency. Generally, HR welcomes the new employee and ensures that orientation covers the basics.

3. The first week. New employees shouldn’t have a letdown after orientation. Colleagues in the new employee’s office—manager, peers, sponsors, and executives—play key roles motivating and acculturating new employees. The new employee should spend some or all of this week doing purposeful work, obtaining the resources he or she needs, and becoming acclimated to the job and the surroundings.

Figure 12.1. Strategic onboarding model.23

4. The first 90 days. The fourth phase covers the time between the new employee’s first week and the end of the first three months of employment. This is when the new employee should complete new employee training. During this time, new employees should begin to take on a full workload while managers/supervisors monitor performance and provide early feedback. Lack of attention to this phase can result in new employees not feeling fully engaged by the end of their first 90 days.

5. The rest of the first year. The last phase is the time between the end of the new employee’s first three months and the end of his or her first year. For most agencies, formal onboarding activities do not extend into this period. But for the employee, the feeling of newness—and the accompanying learning curve—linger. Continued support during this time can help speed employees to full performance. Managers and supervisors should provide formal performance reviews at least at the six-month and one-year marks.

IMPROVE EMPLOYEE WELL-BEING

Forward-thinking government agencies are also beginning to understand that employee well-being and employee engagement are related and that both drive fewer health-related absences and improved productivity and performance.

At the U.K. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA), rates of sick-related absences were cut in half after the agency introduced a preventative strategy that focuses on health and well-being. At the same time, DVLA’s engagement score, measured by the U.K. Civil Service People Survey, increased from 51 to 55 percent. In 2010, DVLA won the Civil Service Human Resource Award, recognizing the agency’s success improving engagement and well-being in support of organizational efficiency.

DVLA has more than 6,000 employees, the majority of whom perform administrative tasks (think Department of Motor Vehicles in the United States). About 75 percent earn less than $35,000 annually. In 2005, DVLA employees averaged 14 sick days per year, costing more than $16 million and leading to a National Audit Office report criticizing the agency.

The DVLA approach to reducing sickness absence focused on three factors: health, well-being, and attendance. Specific goals were to improve well-being and the working environment; move from a culture of “illness” to “wellness”; and develop an engaged, inclusive workforce.

The initial focus involved intervening in ways that would produce short-term results. This involved generating more detailed data about sick absences, reviewing and updating policies and procedures, and developing guides to support staff and managers. DVLA set agencywide attendance objectives and began more intensively managing long-term absence cases by keeping in closer touch with employees during absences and encouraging more proactive rehabilitation. The agency also launched a new training course to help line managers deal with sick-related absences.

In addition to these short-term tactics, DVLA put in place strategies to improve employees’ long-term health and well-being:

• A quality-of-working-life survey, with an action plan to address the issues employees identified

• A health promotion program that focused on wellness rather than illness, including a pedometer challenge, weight management program, and smoking cessation classes

• Proactive occupational health and well-being services that included earlier support for stress-related absences and access to a physiotherapist for musculoskeletal disorders

• Closer links with local doctors to provide employees with better access to rehabilitation assistance

• Employee assistance for staff and their immediate families including a 24-hour telephone counseling service that also provides debt and legal counseling

• Support to improve lifestyles, including a fitness center, marked walking trails around the DVLA building, and bicycling support

• Monthly health promotion events and a focus on mental health in response to increased absences caused by stress and mental-health issues

The agency also regularly analyzes absence data to enable HR to identify attendance trends and take early action to respond. Directors meet monthly to discuss the data and flag any emerging issues in their units.

This DVLA research revealed a direct relationship between employee engagement and overall average working days lost and the proportion of staff without sickness absences. A 10 percent increase in the engagement index correlates with a 1.1 day reduction per employee in average days lost. Similarly, a 10 percent increase in engagement would lead to an 8 percent increase in the proportion of staff with no sickness absence in the preceding 12 months. A unit of 100 employees would have nine fewer absences per year.24

Another U.K. jurisdiction, the Chorley Borough Council, also focused on health and wellness. In 2001, Chorley averaged about 16 sick days per employee, which left it languishing in the bottom 25 percent of all similar U.K. jurisdictions, for sickness and absence. To respond, Chorley created a coordinator position to manage its new health program, “Active at Work,” which included the following:

• Daytime activities such as Pilates, tai chi, and aerobics

• Health-promotion events measuring body-mass index, weight, and blood pressure

• A pedometer challenge, with more than 200 employees taking part in teams during a four-week competition (all participating employees received a free pedometer)

• Screening and support sessions that cover smoking cessation, osteoporosis, free eyesight tests, office ergonomics, and annual flu vaccinations

• A men’s health week, with information on smoking cessation, cycling to work, and health checks

The council also revamped its stress-management program and established a support group called “workplace listeners” to provide employees with trained colleagues who will listen to their problems. Monthly holistic therapies such as massage and reflexology are provided on site at heavily discounted rates.

The result of all this activity was a reduction from an average of 16 sick days annually to less than 8 days lost. The well-being program also translated into improved engagement, including Chorley being ranked number 2 and most-improved in the Times “Best Councils to Work For in 2008” (with a first place in the health and well-being category). The council also received an award for customer service excellence.25

CLARIFYING THE LINE OF SIGHT BETWEEN THE JOB AND THE ORGANIZATION MISSION

I have described how public-service motivation is a strong influence on public servants’ interest in, and commitment to, government. To nurture this commitment, however, public servants must have a line of sight between their work and the mission and achievements of their agency.

The Porirua, New Zealand, City Council (PCC) analyzed the results of its employee-engagement survey and realized that its engagement issues involved leadership, common purpose, direction setting, and internal planning. These line-of-sight issues revealed that what was missing was full staff buy-in to the council’s vision and the new way of working achieving this vision would require.

To help bridge this gap, the council formed a cross-functional team whose charter was to clarify the line of sight between individual employee effort and the PCC’s vision, mission, values, and community outcomes. The team included representatives from each business unit who were close to the frontline and was supported by senior subject-matter experts in communication and marketing, HR, and business excellence. This project was championed by PCC’s CEO, who facilitated the team’s meetings himself. The team was assembled to include employees who were close to the frontline, forthright, creative, and uninhibited by authority.

The team worked on initiatives that included modifying the council’s vision statement, which at 65 words was too long and lacked appeal. The result was a more succinct and compelling message: “Together, we’re making Porirua amazing!”

The team’s next challenge was to come up with ways to excite and engage staff around this new vision and create alignment between staff roles, business-unit purpose, and the newly articulated vision.

The team decided on a series of interactive vision and values workshops that included discussions to help participants understand how they and their teams contribute to the big picture.

Out of 290 eligible council staff, 205 attended one of the workshops. The majority reported that they gained a greater understanding of how their job fits with the goals of their business group; how their job contributes to community outcomes; what inspires them in their work; and how the council’s vision, mission, and values relate to them personally. After the workshops, the number of “engaged” employees increased by 5 percent. Results for specific engagement statements also improved, as shown in Table 12.1.26

In the United States, the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics also strives to help employees see the connection between their work and the results the hospital is committed to. In one best hospital practice, this connection begins with employee orientation, where new hospital employees in one unit are shown some of the letters and positive comments from patients about department employees. This enables the new hire to see, right from the start, how his or her role can directly affect the hospital’s primary customers—its patients.

Table 12.1.

Engagement survey statement |

Positive responses before program (%) |

Positive responses after program (%) |

PCC has a clear vision of where it’s going and how it’s going to get there. |

66 |

70 |

The CEO and executive team help staff understand the council’s vision. |

62 |

67 |

Staff believe in what PCC is trying to accomplish. |

73 |

77 |

There is a sense of common purpose in PCC. |

62 |

69 |

Cooperation between teams is encouraged. |

63 |

71 |

I think it’s worth repeating a quote from a public servant (cited in Chapter 5) about connecting with the people that government serves: “When I found myself getting down, I would head to the frontline. Being among the citizens we served reminded me why I was there and why it was important to keep fighting.”27

ENHANCING EMPLOYEE PROSPECTS FOR CAREER GROWTH

Another important driver of engagement is providing employees with opportunities to develop and grow. This is critical to government-engagement efforts to overcome barriers identified in Chapter 4 that include frequent leadership changes, complicated and inefficient decision making, few financial incentives to affect behavior, and strong civil-service rules that limit the flexibility of both managers and employees.

At the National Science Foundation (NSF), one pillar of the foundation’s consistently strong “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” score is encouraging staff members to actively engage with their research communities by delivering presentations, attending conferences, and making on-site visits to NSF grant recipients. These connections to the scientific community enhance the NSF work environment by broadening the reach and impact of employees’ work.

Oregon Metro has developed a series of training and development programs and identified those that map directly to the leadership competency “engage and develop”:

• Clarifying performance expectations

• Correcting performance problems

• Conducting difficult conversations

• Providing feedback and coaching

• Managing at metro

In the state of Washington, the Information Systems Services Division implemented a series of actions to improve survey scores on the statement “I have opportunities at work to learn and grow.” The division did the following:

• Implemented employee training plans to maintain/advance skills and education

• Created more cross-training and internal-training opportunities within the division, most notably through developmental job assignments

• Encouraged and supported technical certification

• Offered self-paced online training resources

• Closely linked employee training to the agency road map and strategic and tactical plans

Outside the United States, the Careers New Zealand agency took aggressive action to improve employee engagement by creatively expanding career-development opportunities. “Careers” is the national agency that provides New Zealanders with information, advice, and support to help them make career decisions.

Determined to practice what it preaches, Careers decided to extend its use of internal assignments. Despite its success achieving finalist status in the JRA “Best Places to Work in New Zealand” surveys in 2007 and 2008, the survey results also showed that staff wanted better development opportunities and that learning and development was a high priority for staff. These results became the catalyst for a concerted effort to find creative ways to expose staff to new challenges that would utilize and develop their skills.

The Careers approach went beyond just advertising internal transfers and promotions. Instead, staff were encouraged to volunteer for assignments that could mean transferring to a different work group, job, region, or even moving outside the organization temporarily.

The idea was to link people, their skills, their aspirations, and their circumstances to the many and varied opportunities available across the organization. HR publicized the available opportunities and then encouraged employees to take advantage of them.

The program ensured that Careers employees were considered first for opportunities—whether these opportunities were created through new projects, staff movement, or staff taking extended leave. Assignments ranged in length from six weeks to two years.

Specific results linked to the program included the following:

• Recruitment costs decreased by two-thirds.

• Staff turnover decreased from 21 percent to 11 percent.

• Satisfaction with learning and development opportunities rose from 71 to 78 percent.

• Percent of staff who said they feel encouraged to develop knowledge skills and abilities increased from 79 to 85 percent.28

RECOGNIZING EMPLOYEE CONTRIBUTIONS

Recognizing employee contributions and linking this recognition to performance are also keys to improved employee engagement. While this linkage is important in all organizations, it is particularly important in government today, to help counteract the negative images of the public service and public servants.

In many private-sector organizations, superior performance is recognized by pay raises and/or bonuses. But with today’s tight public-sector budgets, government agencies need to find other ways to recognize outstanding performance.

One way to do this is to ask employees how they want to be recognized, as the University of Wisconsin Hospital has done. One hospital director responded to survey data showing that employees were dissatisfied with their recognition opportunities by surveying that unit’s employees to find out how they wanted to be recognized. The hospital took this a step further by developing a “Thanks for Caring Recognition Tool Kit” that describes ways that managers and supervisors can provide on-the-spot recognition to their employees. The tool kit includes the catch phrase, “Reward small. Reward big. Reward the best of the best. Reward today.” The tool kit lists rewards that managers and supervisors can purchase but also includes suggestions on how to thank employees “without spending a dime” that include the following:

• Mail a handwritten note to the employee’s home.

• Offer verbal recognition at a staff meeting.

• Surprise the employee with a Post-it note of thanks.

• Put a thank-you note on the department bulletin board.

• Compliment the employee within earshot of others, and the word will spread.

• Send a department-wide email praising an individual employee or team.

• Start every meeting by recognizing an employee; ask employees to recognize each other.

• Pull an employee aside and ask for his or her opinion.

At the FAA, the administrator implemented an annual “Making the Difference Award,” presented to an agency employee who made an important contribution to improving employee engagement.

Some jurisdictions and agencies have implemented peer-recognition programs in response to employee survey data. The city of Coral Springs, Florida, which has been conducting satisfaction/engagement surveys for 18 years, has what it calls a “layered approach” to employee recognition:

• A peer recognition “applause card” program, in which nominations are submitted online. Nominated employees are placed into a quarterly drawing and can win gift cards. Each month, 400–500 employees are nominated.

• An instant recognition program, which encourages employees or supervisors to nominate colleagues who exhibit the core values of the organization (customer service, empowered leadership, and continuous improvement) or who take on additional responsibilities. Awards are mainly gift cards. The city budgets about $25,000 for this program each year.

• An annual “Employee Excellence Award” program, which also relies on peer nominations. Employees can nominate colleagues or themselves in any of the city’s core value categories or for contributions to improve their organization. All submissions are done electronically and vetted by a committee of prior winners.

As a result of its employee-engagement surveys, the Air Force Materiel Command realized that it needed to do a better job recognizing employees. In response, the command implemented peer recognition programs—including an employee of the month and a “top-dog” employee.

While pay raises are usually not feasible during tough budget times, some public-sector agencies are trying to better link performance and pay. For example, the Government Accountability Office, a perennial leader at the top of the “Best Places to Work” rankings, implemented a performance-based compensation system in 2004. Similarly, according to HR director Dale Pazdra, the city of Coral Springs, Florida, has a “performance-based pay culture” that helps account for its exceptionally high scores on employee-engagement survey questions. Scores on these questions range from 84 to 97 percent positive. Even with tight budgets, the city is continuing its incentive pay program.