______________

Step 4: Taking Action to Improve Employee Engagement

Before this book, I’d written a series of articles on employee engagement, including one subtitled “Free Pizza and Coke on a Friday Afternoon Is Not an Engagement Strategy.”1

My point was that an agency truly committed to improving engagement needs to take real and sustained action to improve engagement. This means going beyond just conducting an employee survey, which is merely the starting point to improve engagement. We can’t improve individual or organizational performance with surveys and data unless we use the results wisely. The city of Minneapolis analyzed survey results, and, according to Charles Bernardy, city HR manager, in the departments where action was taken—and employees knew about it—engagement scores were significantly higher. According to Bernardy, “Employees who say their department leadership took action on the results of the 2009 employee survey are 45 percentage points more engaged.”2 In addition, the following is also true:

• City employees who said they were given an opportunity to see/hear about the employee survey results were 26 percentage points more engaged than those who did to have this opportunity.

• Employees who reported they had the opportunity to discuss their ideas about the results of the survey results were 34 percentage points more engaged than those who did not.3

The Norfolk City Council in the United Kingdom has turned its commitment to act on engagement survey results into a catchy motto: “You said, we did.”4

At the University of Wisconsin Hospital, work units that acted on the engagement survey results improved over time and the units that didn’t act didn’t improve. While this makes intuitive sense, the hospital did the math, made the comparisons, and proved it empirically—a powerful message for an organization with a culture that highly values data.

No matter how an agency approaches taking action, it’s important to understand that improving employee engagement is a long-term proposition. Conducting an engagement survey and then analyzing the results is the beginning, not the end. As a jurisdiction or agency analyzes engagement survey data, it may decide to put in place long-term changes or target specific engagement issues immediately—or both.

Even organizations that have good employee-engagement results/scores can strive to go from good to great. In the “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” rankings I’ve been citing, 71 percent of federal agencies improved their initial employee satisfaction scores when their employees were resurveyed.

The Partnership for Public Service developed an action planning guide to help agencies take action on satisfaction/engagement survey results. The guide includes specific steps a jurisdiction or agency can take to act on survey data:

• Identify focus areas/priorities.

• Find an executive champion and engage key stakeholders.

• Communicate, communicate, communicate.

• Form action teams and create action plans.

• Collect additional data.

• Set measurable goals and milestones.

• Develop recommendations.

• Obtain executive sponsor approval.

• Put the plan into action.5

IDENTIFY FOCUS AREAS/PRIORITIES

It is unlikely that any organization, public or private, could immediately respond to all issues identified in an engagement survey. That’s why it’s important to focus on the survey responses that identify the greatest opportunities to improve. There may be low-hanging fruit where short-term improvement is possible—and may even be necessary. In Chapter 9, I outlined some approaches to analyzing survey data that can help identify the areas that have the greatest potential to improve engagement. The engagement survey questions that are low-scoring but have high importance (the engagement drivers) are a logical place to start. Given that government resources are constrained (and becoming even more constrained), identifying the priority areas of focus is a critical step.

It’s important to emphasize again that acting on survey results isn’t just about shoring up weaknesses. It’s also about focusing on the strengths identified in the survey and then maintaining them.

At the Air Force Materiel Command, action teams were formed to work on issues identified in the engagement survey. These teams were asked to identify two areas of focus in order to maximize the probability of success. The University of Wisconsin Hospital used the same approach—individual departments were asked to identify and then work on two high-priority items.

FIND AN EXECUTIVE CHAMPION AND ENGAGE KEY STAKEHOLDERS

Improving employee engagement requires a shared vision for change that starts with senior leadership, extends to managers and supervisors, and then reaches other employees and stakeholders across the organization, at all levels.

Any organization-wide effort such as improving engagement requires executive-level support. This is a particularly true in government where, as we have discussed, decision making is often diffused and subject to external forces. An executive champion can generate buy-in from internal and external stakeholders and also provide resources. Plus, employees who are energized by their executives’ commitment to improving the agency workplace can themselves become ambassadors for change.

The commitment of managers and supervisors is also a key to improving engagement, regardless of which survey is used. Strong leadership is almost always critical to improving employee engagement, especially in government, where (as we described in Chapter 4) agencies committed to improving engagement face a set of particular challenges, including entrenched workforces.

Unions can also be powerful allies for change, especially since they are still very influential in many government jurisdictions and agencies. Agencies that involve unions in the development and administration of employee surveys—like the city of Minneapolis, Oregon Metro, and the Air Force Materiel Command—have an advantage when they are ready to take action on survey results. In the long run, improving union members’ level of engagement should resonate with organized labor, particularly if unions have been involved in the process from the beginning.

COMMUNICATE, COMMUNICATE, COMMUNICATE

In the words of George Bernard Shaw, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”6 This echoes what organizations that have surveyed their workforces and then successfully acted on the survey results advise—communicate early and often.

As described in Chapter 8, communication should begin even before the survey is conducted. The agency should broadly announce the initiative, including how it supports the organization’s strategy and why engagement matters (i.e., the business case for engagement), and emphasize the agency’s commitment to improving the working environment. Chapter 8 includes the communication guide we used at the University of Wisconsin.

Communication continues after the engagement survey is conducted. Employees who complete the survey will be eager to learn about the results. Not providing this feedback promptly will create a perception that the organization is not serious about improving engagement or, even worse, has something to hide. The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) recommends sharing survey results with employees no later than one month after the jurisdiction or agency receives them.

That’s one reason Oregon Metro posts comprehensive survey data on its intranet so all employees (and labor unions) can see the results. Metro also provides all employees with a written summary of the results. In the city of Juneau, every city employee receives citywide results as well as the data for his or her department. The state of Washington posts the complete results of its biennial employee survey, agency by agency, on the state HR website.

In most organizations, the survey results will be a combination of good news and bad news, and it’s important to share both messages, publicizing areas of strength as well as areas for improvement. For example, when the city of Minneapolis did its first engagement survey, the results identified some clear areas of strength (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1.

Statement |

% Who agree |

I believe the quality of my work is important to the overall success of the city. |

89 |

My work unit provides quality services to customers. |

88 |

The people in my work unit are committed to doing quality work. |

84 |

I understand how my work contributes to the overall goals of the city. |

83 |

I understand how my job helps fulfill my department’s mission and goals. |

83 |

These positive results were impressive and worthy of publicizing. On the other hand, the survey identified areas for improvement that city employees (and elected officials) also needed to know about (Table 10.2).

In the federal government, the “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” results are widely publicized by the Partnership for Public Service through a high-profile release event that includes award presentations to the top-ranking agencies, press releases, and posting of agency-by-agency scores and rankings on the Partnership’s public website. This generates press and other media coverage.

The transparency and publicity generated by the Partnership puts pressure on each ranked agency to also communicate internally with its staff—sharing not just the survey results but also what the results mean to the agency and, more important, what the organization intends to do about them. Shortly after the Partnership released one set of “Best Places” rankings, a federal department secretary announced to his senior managers that his goal was to be ranked in the top 10 the following year. The leadership team got the message directly from the top—that they needed to get serious about employee engagement; this filtered down to frontline employees. While the agency did not make it into the top 10 the following year, it did improve.

Absent the kind of public announcement that the Partnership makes, it is up to each agency to not only share results but also communicate what the organization intends to do about the survey data, including forming action teams, if that’s how the agency plans to proceed.

Table 10.2.

Statement |

% Who agree |

My work is valued by elected officials (mayor and city council). |

32 |

A spirit of cooperation and teamwork exists among departments in the city. |

35 |

The morale in my department is positive. |

39 |

My department manager informs me about how decisions are made and how they affect me. |

41 |

I believe my department is valued by elected officials. |

44 |

As the agency moves forward to act on the survey results, it becomes important to regularly report on progress. At the University of Wisconsin Office of Human Resources, we did this through regular all-staff meetings, a monthly newsletter written and produced by our employee-engagement team, and a series of coffee breaks with the director (me). To keep the number of coffee break attendees down to a number that facilitates a real conversation, we invite specific employees to attend each session. We designed the rotation to ensure that during the year every one of our staff members would be invited (but not required to attend). Government agencies have also used the following methods of communication:

• Individual in-person meetings. Meeting with key internal stakeholders (e.g., key managers, union leaders) individually may facilitate a candid exchange that can help the agency understand and anticipate potential concerns. Similarly, meetings with external stakeholders (e.g., legislators, board members, citizens’ groups) can help create momentum for change, or at least forestall potential opposition, which in government can crop up from many different sources. The city of Minneapolis, for example, briefed the city council on its engagement work to be as transparent as possible and also build council support for the city’s engagement strategy.

• Symposiums and town-hall meetings. When agency leaders and managers participate in organization-wide town-hall meetings to describe and discuss the engagement initiative, employees will see the agency’s commitment and better understand the results and what the agency plans to do about them. Employees also appreciate the opportunity to ask questions and receive immediate answers from senior leaders.

• Electronic communication. Email newsletters, downloadable videos, social media postings, intranet and website announcements, or agencywide blogs can quickly and efficiently share information with large groups of employees.

• Printed memos and posters. The old-fashioned way to communicate can reach employees who don’t have regular access to computers at work.

• Public announcements. Messages can educate external stakeholders, job seekers, and the general public about how the agency values engagement and what it is doing to enhance it. Press releases can generate positive news stories about the agency’s commitment to engagement and improving the workplace.

FORM ACTION TEAMS AND CREATE ACTION PLANS

Many agencies have successfully responded to and acted on employee survey results by forming action teams. These teams analyze the survey data to identify key issues (as described in Chapter 9), conduct further research to diagnose the root causes of these issues, set priorities for action, develop recommendations—and then help implement them.

A common approach to creating these teams is to ask for volunteers. Employees who are personally committed to, and invested in, workplace improvement can be powerful forces for changes grounded in engagement survey data. Bringing this kind of energy to an action team is essential. Selecting committed volunteers also helps reduce the risk of convincing employees to handle the responsibility of serving on these teams in addition to their day jobs. Action teams should be carefully assembled to include employees who represent a cross-section of the agency workforce and who have the right skills to help lead change.

Each team should appoint a team leader—ideally someone who has successfully led a group like this in the past. Agencies may also find it useful to assign a trained facilitator to help the team make decisions and progress. At the university, we made this resource available to each of the engagement teams in the 13 divisions we surveyed. Our facilitators helped the teams get started, analyze survey data, formulate plans, and make decisions. In some cases, the facilitators dropped off after the teams made key decisions and formulated their strategies and plans.

An approach that may seem appealing but is risky in the long term involves empowering managers and supervisors, by themselves, to take action on the survey data. This can seem like an efficient strategy, since managers have the authority and power to make changes that a team of rank-and-file employees typically doesn’t. But this can be fool’s gold. A managers-only approach probably won’t have credibility with frontline employees, particularly if the engagement survey shows that the managers and supervisors themselves are at the root of the engagement problems. Credibility issues like these could damage the ability of the agency to implement real change that is accepted across the entire organization.

At the University of Wisconsin, a few of our units initially decided to have their management teams lead the survey-based change efforts. However, this approach was eventually shelved in favor of teams that represented a cross-section of employees, including labor representatives. At the University of Wisconsin Hospital, each department created its own team to analyze its department-specific survey results, identify two priority issues to focus on, and then come up with approaches to address the two issues.

COLLECT ADDITIONAL DATA

While action teams should rely on engagement survey data as the basis for identifying the key issues, it is also useful to collect additional data, often through focus groups. These discussions can add richness and detail to the survey data, including insights on engagement nuances, as well as the root causes of barriers to engagement. Ideally, these focused discussions will involve open-ended questions and be conducted by a trained facilitator who does not have a stake in the process or outcomes.

The U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), for example, was the third most improved agency subcomponent in the 2011 “Best Places to Work” rankings and improved again in 2012. The BEP prints all the folding money we have in our wallets—billions of dollars a year in U.S. currency. In response to a low ranking in 2010, BEP created a “best places to work committee” that held focus groups that included white-collar workers, employees who do manual labor, midlevel managers, and entry-level employees. The focus groups were designed to take the pulse of the workforce and identify the reasons for the low employee ratings.

The number one concern voiced by employees was lack of communication. To respond, the bureau developed an action plan that focused on letting employees know what was happening in the organization and the rationales for bureau decisions. BEP put mechanisms in place to regularly obtain feedback, act on employee concerns, and let employees know they were being heard.

BEP supervisors, as part of their own performance expectations, began meeting regularly with employees to discuss and address workplace issues, understand what motivates employees, and actively engage them. Bureau leaders also worked closely with union leaders and held offsite meetings to find areas to work together to improve the work environment.7

At the University of Wisconsin, after we surveyed the Office of Human Resources staff, we hosted a series of facilitated focus groups in which we discussed the survey results and also asked participants to respond to the following:

• Recall a time when you worked in a place that had a highly engaging workplace culture. Share an experience from that time that illustrates what made it a “culture of engagement” in your mind. As you talk together, find the key elements that emerge from your stories.

• Have a brief conversation about the “key elements of engagement” that emerged from your anecdotes. What are those key elements? Are there some that especially resonate? Also, describe behaviors associated with each element (e.g., “respect” might also include “respect is shown by listening really carefully to everyone’s ideas”).

• Come up with two to three key elements that should apply to our organization, either because they are already present and should be strengthened or because they are currently lacking and are needed.

The focus group discussions allowed our staff to explain, in detail, how they responded to the survey questions and why. In turn, this allowed us to better understand what our staff’s concerns were and then identify priorities for action.

SET MEASURABLE GOALS AND MILESTONES

Engagement survey data will likely identify important improvement areas (e.g., key drivers of engagement), such as quality of supervision, role clarity, and rewards/recognition. These areas can be the basis for short-term, midterm, and long-term goals, and all should include timelines.

It’s important to confirm what the employee-engagement team is expected to deliver. Here are some clarifying questions:

• What format will the recommendations and action plan take (e.g., memo, report, presentation, some combination)?

• How often will the team check in with its executive sponsor (e.g., regular interim check-ins, one final briefing)?

• Who is the primary audience for any deliverables (e.g., senior leaders, managers, staff)?

• When are deliverables due?

• How will the team’s results be communicated across the agency?

• Who will be responsible for implementing recommendations (e.g., the action planning team, a separate implementation team, senior staff, supervisors)?

• Will there be follow-up deliverables (e.g., to evaluate results)?

Effective action planning also requires accountability. At the University of Wisconsin Hospital, each department is required to publicly post its action plan, and HR makes sure they are all posted. The hospital does not centrally monitor the specific execution of each plan but instead monitors unit engagement scores from year to year.

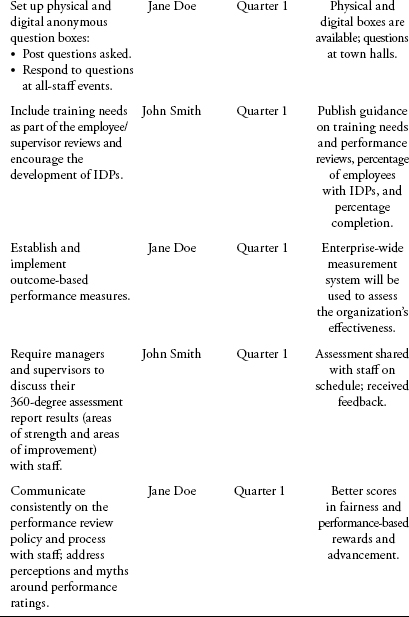

Table 10.3. A Sample Action Plan for Improving Supervision (Adapted From the Partnership for Public Service Model)

DETERMINE BUDGET AND RESOURCES

Action teams should also project costs and review them with the executive sponsor. For example, what are the anticipated costs for the team to analyze the survey results and develop recommendations; what will implementation of the recommendations cost; what other resources are needed; and how will the team coordinate with managers across the organization?

DEFINE METRICS FOR SUCCESS

The team should identify measures of success for both its work (e.g., developing recommendations) and the implementation of priority recommendations. Specifically, how will the teams collect and analyze data to measure outcomes and success; how will the team track the progress of its action plan; how will the team measure the impact of implemented recommendations; and over what time period?

Establishing Action Team Ground Rules

Action planning teams should set ground rules for how they will operate. These may include principles such as respect and striving for equal participation. Teams should also clarify and assign basic roles and responsibilities, such as the following:

• Should the team develop a charter to outline goals, roles and responsibilities, deliverables, milestones, and so on?

• How and how often will the team meet (i.e., in person only, teleconference, videoconference, weekly) and for how long?

• What is the attendance policy (i.e., principals only or substitutes when necessary)?

• Who will serve as team lead?

• If there is an assigned facilitator, what will his or her role be?

• What are the roles and responsibilities of the team members?

• What is the confidentiality policy about team discussions?

• Will the team keep meeting minutes and, if so, who will take notes?

• Who will communicate with the executive sponsor and senior leaders?

• How will the team make decisions?

Sample Template: Action Team Charter

Project name_____________________________________

Executive sponsor Project manager_____________________________________

Primary stakeholder(s)_____________________________________

Project description / statement of work_____________________________________

Business case / statement of need

(Why is this project important now?)

__________________________________________________________________________

Customers_____________________________________

Customer needs / requirements_____________________________________

Project definition

Goals_____________________________________

Scope_____________________________________

Deliverables_____________________________________

Project constraints / risks (Elements that may restrict or place control over a project, project team, or project action)

__________________________________________________________________________

Implementation plan / milestones (Due dates and durations)

__________________________________________________________________________

Communication plan (What needs to be communicated? When is communication needed? To whom? How?)

__________________________________________________________________________

Change management / issue management (How will decisions be made? How will changes be implemented?)

__________________________________________________________________________

Project team roles and responsibilities

Team member |

Role |

Responsibilities |

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Stakeholder roles and responsibilities

Stakeholder |

Role |

Responsibilities |

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

DEVELOP RECOMMENDATIONS

Once the team understands the agency’s engagement challenges, based on the survey results and any additional data (e.g., focus group discussions) and identifies priority areas, the team should develop concrete recommendations to improve engagement. One approach is to begin by brainstorming potential solutions. During this initial brainstorming phase, team members should offer any solution that might address the agency’s engagement challenges. If the team has a facilitator, he or she can lead these discussions.

Another approach is to reach out to agency staff for solutions, perhaps using in-person or online forums where employees can share their ideas to improve engagement and the workplace environment. Employees could even be asked to vote on the ideas submitted, as Oregon Metro asked its employees to do.

Usually, the engagement team will identify a set of recommendations that must be put in priority order. One way to do this is to map the recommendations to the driver analysis (or matrix, described in Chapter 9) that identified the issues that agency employees feel are most critical to engagement and therefore drive their engagement levels. Recommendations that respond to statements/questions in the low-scoring, high-impact quadrant have the most potential to improve engagement. For example, improving the capabilities of supervisors is almost always a high-impact activity (and often a low-scoring area). However, the team should not limit itself just to long-term solutions. Small changes can also be meaningful and demonstrate to employees that the agency is taking action on the survey results.

The team should also evaluate the cost of, and barriers to, possible recommendations. The MSPB suggests creating recommendations that are “SMART”:

• Specific—Clear and concrete, stating in behavioral terms what will happen

• Measurable—Measured and can be evaluated

• Achievable—Practical, giving the organization the capability to actually accomplish the objective

• Relevant—Will make a significant positive difference for the organization

• Time bound—Has specific time parameters8

OBTAIN EXECUTIVE SPONSOR APPROVAL

After the team has identified its priority recommendations, the next step is usually to pitch the recommendations to the executive sponsor for approval and commitment of resources. The team should make a well-organized presentation that summarizes the following:

• What the work team did, including analyzing the survey data and any additional data it collected

• The results of its analysis, including priority areas

• The high-priority recommendations and why the team feels they are most important

• How implementing the recommendations will improve employee engagement and the workplace climate

• A specific plan to implement the recommendations, including a change management strategy

• Resource needs (i.e., money, staff, outside assistance) to implement changes

• How results and progress will be evaluated

• A cycle/schedule for resurveying the workforce

Appendix 1 provides a checklist for evaluating the content and completeness of employee-engagement action plans.

PUT THE PLAN INTO ACTION

After receiving approval and a commitment of resources, the truly hard work begins: implementing the high-priority recommendations. The implementation approach will depend on the specific actions the organization decides to take. The action team could be commissioned to work on implementation, or this responsibility can be assigned to another team, the HR office, individual managers, or another unit.

It’s important for the agency to understand that improving engagement is not just about new policies, programs, or practices. It is often just as much about driving cultural change. This is especially true in government, where workforces and organization culture are usually well entrenched. That’s why FDIC created a “cultural change council” and appointed a “director of cultural change” to help improve its “Best Places to Work” rankings. The result was a number one ranking in 2011 and again in 2012.

The importance of cultural change as a lever to improve engagement becomes clear when reviewing the drivers of engagement. For example, the dimensions of engagement the MSPB identified are as follows:

• Pride in the work or workplace

• Satisfaction with leadership

• Opportunity to perform well at work

• Satisfaction with recognition received

• Prospect for future personal and professional growth

• Positive work environment with some focus on teamwork

Certainly, some of these dimensions, such as satisfaction with recognition received, can be improved by implementing new reward and recognition policies and practices. The same is true for the opportunity to perform well at work, which can be addressed by more robust performance management and employee development. Communication, which underlies much of the engagement model, can also be improved with new policies and practices. However, truly ingraining a culture of engagement often involves an intentional change-management strategy to transform the agency culture.

Effective implementation also requires continual and candid communication. This should include an explicit statement from the executive sponsor reiterating and reemphasizing why actions are being taken, as well as describing the specific actions and milestones. Throughout the implementation process, communication should be regular and widespread across the agency, including progress on deliverables.

Training Managers on Employee Engagement

The University of Wisconsin Hospital depends heavily on its 400 or so managers to take action on its employee-engagement survey results. But the hospital also realized that to make this happen it needed to equip its managers with the knowledge and skills to improve engagement. A key piece of the strategy is a training program for managers, titled “Understanding, Interpreting, and Responding to Employee Survey Results.” The hospital trains all new managers and provides refresher training for managers who have already gone through the full program. The training was originally delivered by the hospital’s employee-engagement contractor, Kenexa, but then the hospital decided to deliver the training itself. The program covers the following:

• Understanding employee engagement and why the hospital measures it

• The engagement survey process

• Survey results, engagement drivers, and priority areas

• Expectations of managers around employee engagement

• Understanding and interpreting work-group engagement scores

• Effectively sharing survey results with employees

• Facilitating an effective action planning session

• Following up