Improving the consumer/packaging interface: smart packaging for enhanced convenience, functionality and communication

Abstract:

Consumer packaging has remained unchanged for decades but today is being challenged to do more. From consumers there is an increasing demand for packaging to be a helpful assistant, not a hindrance, in support of busy lifestyles by improving aspects of convenience and functionality and at the same time demonstrating positive environmental credentials. From brand owners packaging is being asked to help a brand stand out from the crowd, differentiating it in a sea of look-alikes, and underscoring the brand promise in new and novel ways. Smart packaging opportunities are described that can meet these challenges focusing on improvements to the consumer/packaging interface.

11.1 Introduction

Consumer packaging has remained unchanged for decades for almost all types of packaging, with the exception perhaps of shaped and coloured rigid plastic containers and bottles, as the following historical example illustrates. Inside Ernest Shackelton’s 1907 Antarctic hut on Ross Island at Cape Royds are shelves of the original tinned provisions with still readable paper labels indicating their respective contents, which remain after the passage of more than 100 years microbiologically sterile and thus safe to eat, but understandably lacking in taste and texture. They stand as a testimony to the superb effectiveness of, in this case metal packaging, fulfilling the three core functions of product containment, product protection and providing information about the product. If Shackelton were alive today, consumer packaging in the form of paperboard cartons, glass bottles and jars and metal cans would probably be the only item of our world that would be familiar to him.

The traditional roles of packaging have been with us for so long that they are pretty much taken for granted. But today, packaging is being challenged to do more. From consumers there is an increasing demand for packaging to be a helpful assistant, not a hindrance, in support of busy lifestyles by improving aspects of convenience and functionality and at the same time demonstrating positive environmental credentials. From brand owners packaging is being asked to help a brand stand out from the crowd, differentiating it in a sea of look-alikes, and underscoring the brand promise in new and novel ways, at the same time fending off counterfeiters.

Smart packaging has been defined as packaging that does more than the important, though traditional functions of storing, protecting and providing information about the product (Kerry and Butler, 2008). However, in the literature this new type of packaging has been classified in many other different ways: the terms ‘active’, ‘controlled’, ‘intelligent’, ‘diagnostic’, ‘func-tional’,‘communicative’ and ‘enhanced’ have all been used.The all-embracing term ‘smart packaging’ is preferred here, encompassing aspects of packaging design and the incorporation of mechanical, chemical, electrical and electronic forces, or combination of these, within the package. It includes packaging that is active in some way with or without communication to the user. And it also includes the most common form of electronic smart packaging, RFID-enabled packaging.

In this chapter we concentrate on smart packaging for the consumer and brand owner and show and discuss examples, both current and possible future developments, that demonstrate new levels of convenience and functionality and that suggest ways in which it is possible to provide clearer, more effective communication at the consumer/packaging interface.

11.1.1 More demanding consumers

For consumers, the existing functions of bringing the product safely to the shelves and then being part of the buying decision are ‘so what’s’, largely taken for granted. Now in addition, consumers expect packaging to be easier to open and use, to be more convenient and to deliver more functionality.

The packaging industry must also brace itself for an ever increasing demand for ‘elderly friendly’ packaging driven by the demographic changes which will result in significant increases in the percentage of people over the age of 50. The problem is particularly pronounced for the new ‘elderly’, who will be a growing proportion of tomorrow’s consuming generation. The focus will be on better design (size, shape, etc.), and the optimum use of materials, to produce easy-opened packages consistent with the opening strength capabilities of an ageing population. A further challenge for packaging will be the growing information needs of an increasingly technology literate consumer base, the consequences of which will be considered in more detail in Section 11.3.

Frequently, the consumer/package interface does not live up to expectations: from packaging that is difficult to open or dispose of properly, to packaging having instructions in font sizes that cannot easily be read. And having performed its traditional role of protecting and preserving the product, for many people packaging becomes just another inconvenient item to be disposed of, but not until it manages to leave a strong final negative impression on the average consumer. The level of frustration with today’s packaging is so high that it has generated its own media tag: ‘wrap rage’.

Although consumers of the future will be more demanding, the good news is that although many will be older, they will tend to be more technically aware and willing to pay for lifestyle and convenience factors, particularly associated with the consumption of packaged food and beverage products.

11.1.2 More worried brand owners

For brands, differentiation and emotional engagement with the consumer are becoming increasingly essential properties of packaging, but all too often, when new product/package offerings are introduced, they appear to be random and surrounded by an air of desperation. The identification of unmet consumer needs seems to elude most marketeers who react by launching a plethora of new product offerings, largely brand extensions, most of which quickly disappear from the shelves. What we are typically confronted with in a large food supermarket is a huge choice of near identical products that singularly fail to intrigue or engage any of the senses. No wonder so many of us can’t wait to get out of the store. With a few notable exceptions, we are a very long way from the desirable situation where, as Peter Brabeck, the CEO of Nestlé at the time once succinctly put it, ‘packaging is the expression of the soul of every product’ (Hopkins, 2008).

Brands are also being squeezed by private and own labels on the one hand and counterfeiters and look-a-likes on the other. Increasingly, consumers see brands as not being worth the extra cost. Brand loyalty is on the wane as increasing budget pressures lead to many consumers trading down. But brands have personalities and fulfil emotional needs for consumers. Megabrands have the marketing budget to permit a shift of emphasis from remote media advertising to advertising via the packaging at point of sale, where 70% of buying decisions are made. More than ever, on today’s competitive supermarket shelf, the product has to connect with the consumer through its packaging. Consumer/packaging interactions start on the shelf, but they continue as the consumer interacts with the packaging, an event multiplied each time the product is used.

11.1.3 Why packaging must change

For consumers, increasingly hectic lifestyles are creating new demands from products and packaging in terms of user convenience. Whether on-the-go or in the home, consumers are tired of packaging that makes demands on their time and attention; they want first and foremost improved packaging that saves them time, is easier to open and use and helps reduce stress on an already busy life. Any new functionality that supports this consumer environment is likely to be positively welcomed as are improvements to the consumer/packaging interface.

For brands, the key to market success is the ability to emotionally connect with consumers. Current packaging plays a pivotal role in the communication process via colour and shape design elements with basic text information and simple static images, but with the internet and other factors rapidly changing the retail landscape, merchandisers are beginning to question whether going forward these traditional packaging approaches are enough to enhance brand equity or revive weak brands. New ways of using packaging to communicate the brand promise are therefore necessary, and it is established brands that are most likely to benefit from adopting innovative smart packaging features: in doing so they can distance themselves from look-a-like rivals, sustain their position as industry leaders and prevent the erosion of brand value.

11.2 Improved convenience, openability and functionality

11.2.1 Convenience

The main driver for the development of smart packaging is user convenience. Within user convenience, packaging must play to one or more of three key central themes: save time, save money, or provide support by making things easier. Smart packaging without a strong resonance with these themes will be regarded with suspicion or bought once for novelty value only. The simplest smart packaging innovations are those involving elements of packaging design and the appropriate use of materials to create packaging that, without complex functionality, fulfils a very real need for better convenience for consumers.

A simple example is shown in Fig. 11.1 – the tricky problem of removing one or two small pickled gherkins from the glass jar is made more convenient by integrating as part of the packaging a plastic basket with tab that can be raised to bring the gherkins clear of the vinegar solution and hooked over the jar rim once at the right height for product removal.

Fig. 11.1 Smart packaging for improved consumer convenience in product use. For serving, the integral plastic basket allows the pickled gherkins to be lifted clear of the vinegar solution.

Figure 11.2 illustrates another example – the packaging is the integral grater for a piece of fresh Parmesan cheese. The dispenser comes in two grater variants, petals or grated, and is twisted like a pepper mill to dispense fresh shavings or grated Parmesan. It not only protects and stores the product but gives maximum safety during grating since the cutting blades are located internally. The dispenser is refillable and after use can be resealed and easily stored in the refrigerator to retain freshness.

Fig. 11.2 Smart packaging ensures that fresh grated Parmesan cheese is always available with the Dalter refillable package.

In terms of our relationship with when and where we consume food, times are certainly changing, presenting a number of interesting challenges for the packaging industry for food and drink options to be consumed ‘on the go’. In the US, National Eating Trends research finds that 34% of lunches are eaten ‘on the run’ (Dahm, 2002). In the UK, many full-time workers choose not to leave their desks for lunch at all, and many younger people rely increasingly on on-the-go meal solutions bought from local convenience stores. To meet these challenges, many lightweight, single-serve containers that are easily consumed ‘on-the-go’ have been and are being developed. Soup is a favourite with packaging designed for on-the-go portability with an easy-open, microwaveable package that provides a quick meal. Other examples include grab’ n’ go squeezable yogurt in a tube, and fruit to go in single-serve easy peel clear plastic bowls, the perfect size for people who want to eat more fruit but do not have time to wash, peel, chop and prepare it every day.

For al fresco dining and informal picnics, there are also new packaging opportunities as consumers seek out fresh, wholesome foods in ready-made convenient packaged formats. In terms of beverages, possibly the ultimate in convenience is a single-serve lightweight acrylic wine bottle with its own integral drinking glass which also acts as the bottle closure. The Hardy’s ‘Shuttle’ (Anon, 2006) was originally developed for the Australian show-going season of Varekai by Cirque du Soleil, and then launched nationally, redefining how people drink wine, particularly at sporting and other outdoor events, concerts and performances, where glassware is not permitted for safety reasons. The ‘Shuttle’ features a 187 ml (single serve) acrylic wine bottle, opened by a simple twist-top action, which also releases the glass cup into which the wine is poured.

Microwave heating and cooking has led to a number of smart packaging innovations driven by the desire for greater levels of consumer convenience, not only in microwaveability but also in portion sizes. High steam pressures shorten cooking times and this has lead to the development by many food processors of packaging for microwaveable products that allows steam pressure to build up to an optimal level before self-venting. Even more sophisticated for microwaveable products that require browning is packaging with datamatrix (smart code) barcoding (see also Section 11.3.2), permitting communication with a smart combination microwave in the kitchen, resulting in a microwaveable ready-meal precisely heated and browned for the table (Butler, 2009).

For products that require heating or cooling to achieve the best temperature for serving, the simplest packaging addition is a thermochromic label. J.M. Smucker’s Hungry Jack® has had a microwaveable reheatable syrup container with a thermochromic label since 1994. Beer drinkers have also discovered the advantages of knowing when their beer is at the perfect temperature for drinking, and thermochromic printing directly on metal cans and on paper labels is growing in popularity. For example, in the UK a Carling beer can has a lion-shaped temperature-sensitive logo which changes from a silvery/white to blue when the can’s contents reach the right drinking temperature (Molson Coors Brewing Company, 2010).

In the home, consumers want conveniently packaged food products that can be quickly made into meals without sacrificing quality, hence the current flush of microwaveable products, zippered pouches and salad kits. For retailers, convenience packaging provides consumers with greater overall product choice while the packaging is often also utilized as a dispenser, making the product easier to display.

11.2.2 Openability

For many consumers today’s packaging is characterized by a significant level of frustration related to openability. One of two things typically happens: either the package tears and becomes unusable for further storage of the product, or despite consumers’ best efforts, the packaging refuses to open. When this happens, frustration builds followed by the search for a solution by using knives and other sharp implements, greatly increasing the chances of personal injury. This is not a trivial issue. The number of people hospitalized in the UK because of non-medicine packaging related injuries was over 66,000 in 1994 at an estimated cost to the government of approximately £12 million (DTI, 1997), and according to the National Safety Council in the US, 207,680 people went to the hospital in 2005 for injuries related to household containers and packaging (Ross, 2008).

There are plenty of excellent studies giving clear guidelines on designing easier-to-open packaging (e.g. Galley et al., 2005). What is needed is an underlying packaging ‘design-for-all’ philosophy where changes are made to the designs of consumer products so that the greatest number of members of society can use them.

The convenience and requirement of easy openability frequently goes hand-in-hand with that of resealability for food products that are not consumed in a single event, such as biscuits. Unfortunately many products are easy to open but the packaging is destroyed as a receptacle to hold any product that remains. Figure 11.3 shows an example: the tear strip is easily operated to expose no less than four biscuits ready to be eaten. According to Lockton (2006), this is an example of subversive and bad packaging designed to force a function – in this instance an increase in product consumption by making it ‘inconvenient’ not to eat more biscuits than a consumer actually wants. Suppose a consumer only wants a single biscuit, how does he or she store the remainder? It would be much better to package biscuits in an easy-open, easy-reseal container as Nabisco (Kraft Foods) have done for some of their key brands. The Snack’ n’ Seal packaging shown in Fig. 11.4 consists of a thermoformed tray for horizontal flow wrapping, with a reclosable feature on the top panel made up of a precision die-cut opening with a resealable pressure sensitive label. Consumers can open the pack by peeling back the ‘Lift here’ tab and reclose it with light finger pressure.

Fig. 11.3 Typical biscuit packaging having a tear strip well down from one end – easy to open, easy to overeat the product, but impossible to reseal.

Fig. 11.4 Easy open, easy reseal biscuit packaging in marked contrast to Fig. 11.3.

11.2.3 Functionality

Consumer smart packaging is capable of creating products with unique attributes that would not be possible if it were not for the packaging. One of the oldest examples is the widget – a little plastic device inside a beverage can – that was developed to generate a creamy head on canned beer, driven initially by the desire to create the same ‘look and taste’ for canned Guinness that was found in the draft versions in pubs. Functionality can be conferred on packaging by smart structural design alone or by the incorporation of mechanical, chemical, electrical or electronic functionality within the package design, and these functionalities can be combined. Some examples are packaging that provides:

• customized mixing of two slightly different products,

• a unique product appearance and/or attributes,

• self-heating and self-cooling of products, or

• storytelling for brands (discussed in Section 11.3).

Customized mixing

Customized mixing and dispensing provides a new level of convenience for consumers in food products where personal preferences regarding strength of flavour differ, such as in hot sauces. Dialpack is an innovative dispensing pack developed by German company Variotec which allows dual dispensing of two products in variable proportions from 0 to 100%. The two substances are drawn from their two separate cartridges by the pumps, mixed by a static mixer and then dispensed from a pump- or spray-style closure. By rotating the dispenser head, the consumer can then dispense the required proportions of the two products, which mix at point of dispense. Developed initially for H&B products such a suntan lotion, etc., there has been to the author’s knowledge, one food related product: Dave’s Adjustable Heat Hot Sauce (Hot Sauce World, 2010). Very hot sauce is contained in one compartment and milder sauce in the other, allowing consumers to adjust the ratio to their own personal taste (Butler, 2009).

Unique product attributes

The international drinks industry provides a further example of dual dispensing of two components to create a unique final product, facilitated by the packaging. Sheridan’s is a two component liqueur where a white vanilla crème liquid is floated onto the surface of a dark coffee-chocolate base, resulting in a drink similar in appearance to an Irish coffee. The original packaging system consisted of two separate but joined bottles with separate screw cap closures that gave consumers problems in reliably creating this drink. Development efforts culminated in a smart closure system that allowed simultaneous dispensing of the two liqueurs with control of the return air flow in a fool-proof manner to create the ‘perfect pour’.

In other market sectors there are smart packaging examples where the packaging allows two incompatible product components to be combined at point of use. The packaging makes it possible to deliver a combined product of two ingredients that would either separate, not be shelf stable, or would chemically interact if packed together.

Self-heating and self-cooling products

Despite the promise and numerous false starts, we are still far from the situation where consumers can purchase these items in an everyday store. The history of their development and current status have been well documented (Butler, 2006, 2009), so where is the great opportunity for these types of smart packages, or are we doomed to gaze indefinitely upon the many great technical ideas for self-heating and cooling packaging in the trophy room marked ‘the future’?

For both types of container, high cost, lack of reliability and the fear of consumer litigation appear to be the key factors inhibiting commercialization. But the market potential is huge and we must wait for materials/ manufacturing/technical breakthroughs to make them cheaper, lighter, smaller and more reliable. Of course, resistance to innovation in food and beverage packaging is hardly uncommon when cost is factored into the equation. But with beverages alone there are over 100 billion beverage containers sold each year in the US and in excess of 50 billion in Europe, so it only needs a small market share to be self-cooling (or self-heating) to produce some mouth-wateringly large dollar numbers.

11.3 Providing clearer, more effective communication

Both at point of sale and during subsequent use and disposal, there are opportunities for stronger, more visual communication on packaging to consumers informing them about the utility, condition and characteristics of the product. A key brand owner need is to reinforce the brand message which frequently involves communication about the provenance or history/ tradition of a brand (storytelling). The opportunity of moving to non-text-based communication opens up the possibility of significantly strengthening this emotional brand connection by the use of lighting effects, arresting and moving images, and sound.

11.3.1 Communication by packaging design

Provenance in brands needs to be communicated in a manner that is arresting to the potential consumer, who is typically bombarded with a plethora of packaging all looking very similar in a store. It is a long day’s march to find any package that stops you in your tracks - that communicates instantly the essence of the brand and in a totally visual manner.

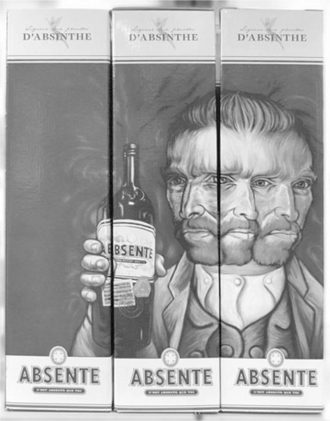

American artist Ron English painted ‘Three Heads’ for Absente absinthe, linking the relaunch and relegalization of the wormwood-containing green liqueur after years of been banned, with the history and tradition of the drink as a favourite with French artists of the nineteenth century, famously the troubled painter Vincent van Gogh. The liqueur is boxed in a standard printed carton but with the painting reproduced across three of the four long vertical sides of the carton. When three cartons are correctly set side-by-side, the full picture is revealed (Fig. 11.5). Using multiple packages side-by-side in this way to increase consumer awareness of a brand by visual means can be an effective visual communication tool if shelf space allows.

11.3.2 Communication by datamatrix barcodes

Cameras as part of mobile (cell) phones are now virtually universal, and wi-fi enabled handsets are becoming so. These types of phones are increasingly essential and commonly carried items of equipment for more and more of the population, presenting the opportunity for consumers to interrogate an item of packaging for product branding purposes or in the case of food, for recipe, nutritional and other information. It gives both consumers and brand marketeers a new communication channel. Gaining a predominant position is a simple two-dimensional barcode, developed in Japan, known as QR code, commonly found on items such as the front of magazines which, when interrogated via the camera, directs the consumer to a website were they can find competitions, downloads or discount coupons.

Portuguese wineries have just started using QR codes on their wine labels (Park, 2010) (Fig. 11.6). The barcode directs consumers to a website where an online community of wine lovers provide reviews and other useful information about that particular wine. The stand-up retort pouch of Heinz pumpkin soup sold in Japanese grocery stores (Fig. 11.7) provides a further example. Reading the code via the camera phone immediately links the consumer to the Heinz website to provide preparation and alternative recipe information.

11.3.3 Communication by lenticular labels

Simple communication about the attributes of a product, or about the provenance of the brand, can be directly and effectively represented visually through a lenticular graphics label applied to the packaging. The technology has been applied extensively over the years to CD, movie and magazine covers, toys, greetings cards, book covers, postage stamps, bottle labels, and other novelty items. The optical effects cover flipping, zooming and morphing images and with new lens technology and higher print resolutions, up to 3 seconds of animation. In the past, much of these applications have been little more than visual tricks, with poor resolution of the lenticular images and the effects lacking any connection with an overall branding strategy.

Opportunities now exist for brand owners and package designers to use high resolution lenticular imaging on package labels in more sophisticated ways to convey a brand’s values or communicate useful information to the consumer. Lo Tengo (The Tango) is a Malbec wine from Argentina that uses an atmospheric black-and-white photograph of a couple of lovers dancing the tango on a paved street in Argentina as the basis of a lenticular label on the wine bottle. The dancers are shown knee to toe only and flip back and forth as the consumer changes the angle of viewing of the label or walks past the bottle (Fig. 11.8), suggesting something of the passion of old-time Argentina.

11.3.4 Communication by colour change labels

Colour change labels are one of the simplest ways of rapidly communicating with the consumer about the condition of a product, and thermochromic labelling for food and beverage products has already been touched upon in Section 11.2.1. For the food sector, there are now smart labels that irreversibly change colour to indicate temperature excursions (hot or cold), the passage of time, product freshness, produce ripeness or overall shelf-life deterioration for perishable food products (Kerry and Butler, 2008). They are inexpensive, reliable and most rely on simple diffusion-controlled colour-change processes, often involving a pH change to trigger an indicator dye. Their use as a means of monitoring food quality and safety is predicted to be helpful in reducing the mounting problem of post-consumer food waste (see Chapter 20).

11.3.5 Electronic opportunities: LED lighting

The relatively simple forms of consumer and brand-oriented communication discussed in the previous sections are printed solutions contributing either nothing or at most a few cents to the cost of the package. The move to electronic types of smart packaging using conventional silicon device circuitry is a step change in terms of increased cost at least at the current stage of technological development, mainly because of the need to include battery power, suggesting applications only for top-of-the-range brands or product launches and promotions.

LED lighting on beverage products can attract consumers and influence buying decisions, at least in the short term. Cognifex has developed a range of licensable electronic smart packaging solutions using LEDs that it claims are set to revolutionize the use of the bottle, can, jar and dispenser as a packaging medium. The ‘LightPad’ consists of tiny LED-driven electronic devices that are attached to the outside, generally in the base recess, of standard glass and plastic containers. The devices are approximately 3 mm thick and have a self-contained coin cell power source and a rubberized outer casing so they can be moulded to the contours of the base of the bottle.

The lighting effects, of differing colours, can be made time variable to start after a specified period of time or after specified conditions have occurred. In a night-club, for example, the lighting effect could last for 20 minutes for a consumable beverage in a 330 ml or 12 oz bottle, representing a typical average consumption time (Fig. 11.9). For other applications, such as those where the effect is required to attract attention whilst sitting on a shelf, the effect would last much longer, for example months, depending on battery capacity. Ursus Breweries in Romania has used the LightPad LED technology to illuminate 330 ml beer bottles for a series of launch parties (Ellis, 2008).

Fig. 11.9 Cognifex LightPad technology uses LED illumination in the base of bottles of alcoholic drinks for product marketing and promotional purposes.

In the future it is envisaged that the principal application area is for product marketing, brand enhancement and promotional activities, particularly when remotely triggered, although these newer applications will be costly. Activating a lighting event using an FM radio signal is possible – for example, if a consumer was holding a winning bottle when Radio Station X transmits a special signal, it would glow a specific colour to show that the consumer had won a prize. Other applications are planned linking the sending of text messages from bottles and containers to mobile phones.

11.3.6 Electronic opportunities: electroluminescent labels with sound

Storytelling in high-end products aims to infuse a product with authenticity and uniqueness and appeals to the discriminating consumer for whom price-per-ounce is relatively unimportant when compared to the creation of a good feeling in selecting the product.

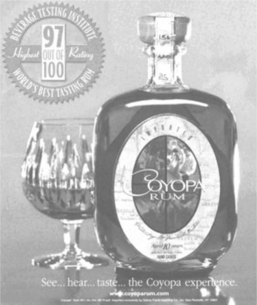

One possibility is the use of conventional silicon device circuitry with electroluminescent illumination and sound chip technology driven by button or coin cell battery power, and a $50 bottle of Barbadian rum shows what can be achieved. The vision behind Coyopa was to create a ‘dancing bottle’ that would capture the imagination and appeal to all the senses –sight, hearing as well as taste – the first ‘rum for all your senses’ (Fig. 11. 10). The electronics are contained in the base of the bottle in a waterproof plastic case barely 5/16 inch (8 mm) thick. This contains the EL inverter (delivering 80/100 V AC power to the electroluminescent label), sequencer, sound chip and associated electronics powered by 3 V lithium coin cells. From one side of the enclosure, thick film printed circuitry leads up the paper-thin composite label consisting of four EL backlit picture quadrants showing Caribbean dancers in action. A small activation switch ensures that each time the bottle is lifted the song and illuminated label dance routine will play once for fifteen seconds, and then shut off automatically. In action, the EL light illuminates the four quadrant pictures of dancers in sequence, giving the illusion that the dancers are moving (Fig. 11. 11), while a sound chip plays a clip of specially composed steel drum music in time with the dancing.

11.3.7 Electronic opportunities: future developments

The key technological challenge to be overcome for ubiquitous electronic smart packaging can be simply stated: the development of high speed, low cost reel-to-reel printing, either of an adhesive label or directly onto the packaging, of thin film transistor circuits, complete with printed power source, sensors, sound capabilities and high-brightness visual displays. Although this is not an insurmountable challenge, and there is much activity in this technological area, it is likely to take a decade or more before it is realizable for high-volume commodity packaging.

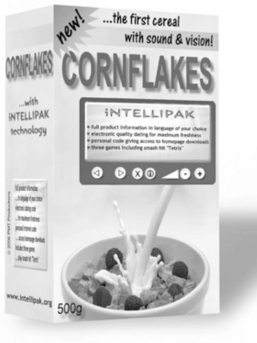

Until then, we are left to imagine a future where even the humble cereal package has sound and vision electronic functionality, as portrayed in the 2002 Spielberg sci-fi film Minority Report, set in 2054, or provides breakfast entertainment in the form of a simple game for children, as in the concept illustration of Fig. 11.12.

Fig. 11.12 Electronic smart packaging of the future might start with simple breakfast entertainment for children.

One of the larger potential markets that will justify printed electronic technology is the potential for electronic self-adjusting use by dates on short shelf-life consumables. The one certainty about today’s printed use-by dates on food, drink and medicine is that they are wrong, because they fail to take into account variations in the most important factor affecting shelf life, namely temperature. Such developments will ensure that part of the responsibility for the safe, cool storage of perishable products is transferred to the consumer, with whom food safety problems can originate due to insufficiently cold refrigerators and poor attention to cool storage particularly in warm weather. Buying perishable groceries on a hot summer’s day and then keeping them in the car for several hours while other shopping is done may be extreme but is not uncommon. Self-adjusting electronic use-by dates will be capable of compensating for such behaviour to protect the consumer, as shown in the concept illustration in Fig. 11. 13.

Fig. 11.13 Electronic self-adjusting use-by dates in the future will monitor and if necessary adjust the use-by dating on perishable food products to ensure consumer safety. In this concept drawing, the use-by date on arriving home has been automatically reduced by two days following in-car temperature abuse associated with shopping on a hot day.

11.4 Drivers and barriers to adoption

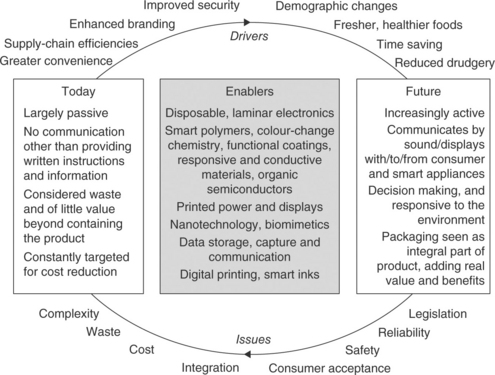

The drivers, issues and technological enablers for packaging to move from a passive component to an increasingly active and supportive one are shown in Fig. 11. 14. The technology enablers for this journey are predicted to be strongly materials-based, drawing heavily on the development of new and novel materials. Smarter packaging will extend the traditional functions of protecting, containing and informing to also include an ability to enhance the product and the brand together with aspects of product consumption, safety, convenience and security. To do these things, the traditional packaging materials – glass, metal, plastic and paper/board – will need to be modified by the incorporation of smart and functional materials, deposited largely as coatings and as part of printed labels and thin film electronic devices.

But there are significant barriers to adoption as the figure illustrates. Some of the packaging examples shown and discussed in this chapter may be rejected by consumers in terms of sustainability, regardless of the improvements in convenience and functionality that they may provide. In addition, food retailers have an increasingly powerful position in deciding how our food gets packaged, and sensors and other electronic features on packaging might be strongly resisted. However, a 2006 pan-European survey on factors affecting consumer acceptance of smart packaging, such as freshness and other quality parameters on perishable food products (SustainPack, 2006), suggested that consumers by and large would welcome their adoption, so long as they were given the required level of education to help them understand the functions of a specific indicator or sensor. The real sticking point appeared to be the attitude of the all-powerful retailers, who suggested that the technology should mainly be used within the logistics area and they would not accept consumers reading label sensors. On the other hand, they believed that it was important that whatever they did it would be necessary for the consumer to accept the technology, creating a curious paradox between the two statements.

11.5 Conclusions

Smart packaging need not use new technologies or be complex to offer real customer benefits – considerable opportunities exist to use current technologies in more imaginative ways. Better convenience in product use, and improved openability and resealability are all appreciated features of packaging, providing simple but useful functionality that can make a difference to consumers.

Real communication opportunities need not wait for the commercialization of cost-effective printed electronics on packaging, although these will come. Advances in non-electronic technologies such as colour-change chemistry, lenticular graphics and datamatrix barcodes can today offer a conduit to better story-telling about a brand product’s attributes, provenance, how the product can be used, or provide useful product information in an easily understandable communication format for the consumer. For example, combining lenticular graphics with conventional silicon sound chip technology can support printed instructions and improve total communication effectiveness about product use. When electronic smart packaging does come, it will be as much about improving the human interface as about providing new functionality. As always, the key to successful consumer smart packaging is to understand unmet consumer needs and translate them into improved products.

11.6 References

Anon, Hardy “Shuttle” Launches a New Era in Global Wine Industry. Food Ingredients First 2006;. http://www.foodingredientsfirst.com/news/Hardy-Shuttle-Launches-a-New-Era-in-Global-Wine-Industry.html [Available from: (accessed 25 August 2010)].

Butler, P., Self-Heating and Self-Cooling Packaging – Latest Developments and Future Directions. IDS Packaging – White Paper 2006;. http://www.idspackaging.com/Common/Paper/Paper_219/SelfHeatingSelfCooling%20Packaging_LatestDevelopments.htm [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Butler, P. Smart Packaging – Providing Improved Convenience and New Functional Benefits for Consumers. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology, 3rd edn, New York: Wiley; 2009:1124–1134.

Dahm, L., Soup goes portable: with Soup at Hand, consumers can take soup to places it has never been before. Stagnito’s New Products Magazine, November 2002, 2002. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-10010788_ITM [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

DTI, Domestic accidents relating to packaging Volume 1. 1997. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/tna/+/. http://www.dti.gov.uk/homesafetynetwork/pdf/domacc1.pdf/ [November 1997, URN 97/956. Available from:, (accessed 24 August 2010)].

Ellis, J., Cognifex launches LED packs for beverage sector. Packaging News. 2008:12. http://www.packagingnews.co.uk/RSS/News/816680/Cognifex-launches-LED-packs-beverage-sector [12 June. Available from:, (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Galley, M., Elton, E., Haines, V., Packaging: a box of delights or a can of worms? The contribution of ergonomics to the usability, safety and semantics of packaging. FaraPack Briefing 2005: New Technologies for Innovative Packaging. 2005:12–13. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/bitstream/2134/3105/1/PUB515%20Packaging%20a%20box%20of%20delights.pdf [October. Available from:, (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Hopkins, G., Disrupting the Printing Ecosystem Available from: Conference presentation in HP’s Annual Imaging and Printing Conference, San Diego, California, 2008. http://www.hp.com/hpinfo/newsroom/press_kits/2008/ipgconference/nr_arprdisruptivetechnologies.pdf [(accessed 24 August 2010).].

Hot Sauce World, Company information. 2010. http://www.hotsauceworld.com/daadhehotsa7.html [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Kerry, J., Butler, P. Smart Packaging Technologies for Fast Moving Consumer Goods. London: Wiley; 2008.

Lockton, D., Forcing functions designed to increase product consumption. 2006. http://architectures.danlockton.co.uk/2006/07/09/forcing-functions-designed-to-increase-product-consumption/ [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Molson Coors Brewing Company, Company information. 2010. http://www.carling.com/beer/strikecold/thermochromiccan [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010)].

Park, J., QR codes: a new dimension. Packaging News 2010;. http://packagingnews.co.uk/channel/converting/news/980776/ [3 February, Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Ross, A., Hard-to-open packaging fuels consumer "wrap rage". The Palm Beach Post. 2008. http://www.palmbeachpost.com/business/content/business/epaper/2008/11/23/a1a_wrap_rage_1124.html [23 November, Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].

Sustainpack, Desk Study on Reports made by Organisations or Institutions on Consumer Acceptance related to Communicative Packaging, D 6.25. Funded by the Nanotechnology RTD programme of the European Union. 2006. http://www.sustainpack.com/project%20reports/DTI_D6.25.pdf [Available from: (accessed 24 August 2010).].