CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To define exchange rates and explain how they are determined.

To introduce foreign exchange markets, and to identify some factors that cause exchange rates to fluctuate.

To identify the major categories into which international financial transactions can be placed, and to understand their interrelationships.

To define balance of trade, and to review its performance over the past few decades.

To introduce the debt problem faced by some countries and issues in unifying monetary systems.

Chapter 16 focused primarily on the exporting and importing of goods and services. But many other types of international transactions are important to an economy: the buying and selling of foreign stocks, bonds, and other assets; foreign assistance; and private gifts to foreigners.

Most international transactions involve payment flows between countries, making it necessary to have a mechanism for determining the values of foreign currencies and for exchanging domestic money for foreign money. The value of an economy's currency in foreign exchange markets is especially important because it affects the prices of the country's exports, imports, and foreign investments. The value of the dollar in relation to the yen, euro, and other foreign currencies is so important to U.S. international transactions and to the economy that it is quoted daily in many news broadcasts, in most major newspapers, and is easily found on the Internet.

The first part of this chapter deals with exchange rates between countries' currencies, how exchange rates are determined, and how foreign exchange markets operate. The second section of the chapter explains how different types of international financial transactions affect payment flows between countries and how these transactions are classified in the United States for analysis purposes. A discussion of the balance of trade, an important and often-referred-to transactions classification, is included in this section. The chapter closes with a discussion of two current problems in international finance: the external debt crisis caused by the inability of some countries that have borrowed heavily from foreign lenders to repay their loans, and issues encountered in forming a unified monetary system among countries.

EXCHANGING CURRENCIES

Exchange Rates

U.S. goods, services, and investment opportunities—such as stocks, bonds, and real estate—carry price tags that are expressed in dollars. You can buy a particular car for, say, $30,000, or invest in a piece of farmland for, say, $4,000 per acre. Regardless of whether the individual who buys U.S. goods, services, or assets is from the United States, Poland, Indonesia, or some other nation, payment for these items is usually made in dollars. Similarly, buyers and investors, regardless of their nationality, typically pay pounds for British goods and yen for Japanese goods. Thus, importing from or investing in another country requires converting one's money into the money of the nation with which one is dealing. An importer in the United States who buys Japanese cars will need to convert dollars to yen to transact business with the Japanese auto manufacturer, and a Chinese student with yuans from home will need to convert them to dollars before paying U.S. tuition.

Importers and investors need to know how much foreign goods, services, and investment opportunities cost in terms of their own money. The U.S. importer of Japanese automobiles must know not only how many yen each car will cost, but also, and perhaps more importantly, how many dollars that price represents. To determine the dollar cost of a car purchased from Japan, the U.S. importer must know the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen.

The exchange rate between two nations' currencies is the number of units of one nation's currency that is equal to one unit of the other nation's currency. For example, the exchange rate between the Swedish krona and the dollar might be 10 krona to $1, or 1 krona to $0.10. At this exchange rate, a product selling for 400 krona in Stockholm could be purchased by a U.S. tourist for the equivalent of $40. If the exchange rate were 5 krona to the dollar, then each krona would be equal in value to $0.20, and the same 400-krona product would cost the tourist the equivalent of $80.

Exchange Rate

The number of units of a nation's currency that is equal to one unit of another nation's currency.

TABLE 17.1 Exchange Rates between the U.S. Dollar and Selected Foreign Currencies (May 22, 2012)

The exchange rates between nations' currencies are constantly changing as economic and noneconomic conditions change.

Source: Source: Exchange Rates: New York Closing - Markets Data Center - WSJ.com, http://online.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/2_3021-forex.html.

Exchange rates between the U.S. dollar and several foreign currencies are given in Table 17.1. Using the British pound as an example, Table 17.1 shows that on May 22, 2012, one pound was worth $1.576 or 0.635 pounds would have exchanged for $1 ($1/1.576 = 0.63451).

Notice in Table 17.1 that there is a listing for the European Union. This is because EU member countries, such as France and Germany, went to a common currency called the euro. Notice also the differences in the exchange rates between different countries' currencies and the dollar. For example, about 14 Mexican pesos were needed to exchange for one dollar, while more than 1,100 South Korean won were needed to exchange for one dollar. Put differently, one peso was worth about 7 cents while a Korean won was worth about 9 one-hundredths of a penny.

The exchange rate quotations in Table 17.1 are for one day only. This is because exchange rates between nations' monies are continually changing in response to economic and noneconomic factors. How and why these rates change will be discussed shortly.

The Determination of Exchange Rates

Today most nations are on a flexible, or floating, exchange rate system. In the past, however, many countries, such as the United States, operated under a system of fixed exchange rates. While the United States abandoned this system in late 1971, the terms and mechanics associated with a fixed system are worth understanding. From time to time, the topic of fixing rates resurfaces.

Fixed Exchange Rates Before adoption of a flexible exchange rate system, exchange rates between the dollar and many other currencies were based primarily on gold; that is, the value of the dollar and other currencies was expressed in terms of the amount of gold one unit of each country's currency would command. For example, if $1 was worth 1/35 of an ounce of gold, and if 4 German marks were worth 1/35 of an ounce of gold, then the exchange rate between the dollar and the mark would have been $1 equals 4 marks, or 1 mark equals $0.25.

Fixed Exchange Rates

Exchange rates fluctuate little, if at all, because the values of nations' monies are defined in terms of gold.

Because the values of their currencies were based on gold, nations were on a fixed exchange rate system. As a result, the exchange rates between their monies generally did not change or changed through a very narrow range. The only way a major change could occur in exchange rates was if one nation redefined the value of its money in terms of gold: for example, if the United States were to have declared that $1 would be worth 1/40 rather than 1/35 of an ounce of gold.

Devaluation

The amount of gold backing a nation's monetary unit is reduced.

When a country declared that its monetary unit would be backed by less gold than previously, that country devalued its money. Devaluation of a nation's money constituted an important international economic policy tool because it changed all exchange rates between the devaluing nation's money and all other monies. This in turn had an effect on international trade, investments, and other transactions. For example, when the United States devalued the dollar prior to 1971, it made the U.S. dollar worth less in international transactions and other countries' monies that were backed by gold worth more. This would then require more U.S. money to buy one unit of foreign currency and less foreign money to buy one U.S. dollar. The result was to encourage foreign purchases of U.S. items because U.S. items became cheaper to foreigners, and to discourage purchases of foreign items by those in the United States because foreign items became more expensive.

Flexible Exchange Rates Today, economies are typically on a system of flexible, or floating, exchange rates, where the rates at which nations' monies exchange are determined by the forces of demand and supply. As demand and supply conditions change, exchange rates change. In the United States as elsewhere, people who are planning trips to another country or planning to make foreign investments watch the movement of exchange rates as they make decisions. When supply and demand result in a strong dollar, for example, people in the United States take more trips to Europe to shop and sightsee.

Flexible (Floating) Exchange Rates

Exchange rates that fluctuate because they are determined by the forces of demand and supply.

The process of determining exchange rates under this system can be illustrated with a hypothetical example involving the U.S. dollar and the Brazilian real. A hypothetical demand curve for Brazilian reals by those with U.S. dollars who want to import Brazilian goods, take advantage of Brazilian investment opportunities, or travel to Brazil on vacation is illustrated in Figure 17.1. The horizontal axis indicates the quantity of reals demanded, while the vertical axis shows the price in U.S. dollars that must be paid per real. As expected, the demand curve is downward sloping: At a price of $0.75 per real, 200 million reals are demanded, while at a price of $0.15 per real, 700 million are demanded.

The reason for the inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of Brazilian reals is that as the dollar price of reals goes up, the prices of Brazilian goods, services, and investment opportunities also increase for buyers wanting to convert their dollars to reals. With Brazilian goods, services, and investment opportunities becoming more expensive for these buyers, they want to purchase less, causing the quantity of reals demanded to be lower.

For example, suppose that a Brazilian travel agency has a vacation package with a price tag of 8,000 reals. At an exchange rate of $0.30 = 1 real, the cost of the vacation would be $2,400. If the price of reals to U.S. buyers were to rise to $0.45 each, the same 8,000-real vacation would cost $3,600. This higher dollar price would cause fewer U.S. buyers to want to purchase this package, which in turn would lower the quantity of reals demanded.

The supply curve for Brazilian reals is given in Figure 17.2. This curve shows the amount of reals available at various dollar prices in this foreign exchange market. The supply curve is upward sloping: At a price of $0.15 per real, 100 million reals would be supplied, and at a price of $0.75 per real, 600 million reals would be supplied. The supply of reals in this market comes from individuals, businesses, and governments that want to purchase U.S. dollars with reals. For example, a Brazilian investor who wants to buy stock listed on the New York Stock Exchange will need to convert reals to dollars in order to complete the stock transaction. The curve slopes upward because as the dollar price of reals increases, the real is worth more in terms of the U.S. goods, services, and financial assets that it can purchase, causing those holding reals to want to convert more of them to dollars.

FIGURE 17.1 Demand Curve for Brazilian Reals by Those with U.S. Dollars

A demand curve for foreign money is downward sloping, indicating that less of the money is demanded as its price increases.

FIGURE 17.2 Supply Curve of Brazilian Reals by Those Wanting U.S. Dollars

A supply curve of foreign money is upward sloping, indicating that more of the money is made available as its price increases.

FIGURE 17.3 Supply of and Demand for Brazilian Reals

In a flexible exchange rate system, supply and demand determine the exchange rate for a nation's money.

The rate of exchange between the U.S. dollar and the Brazilian real can now be determined by combining the supply and demand curves, as is done in Figure 17.3. Given these supply and demand conditions, the exchange rate that emerges is shown at the intersection of the two curves: $0.45 = 1 real. At this rate, the number of reals supplied by sellers and demanded by buyers who want to convert U.S. dollars and reals is 400 million.

Understanding Foreign Exchange Markets

A foreign exchange market is one in which the currencies of two nations are traded. With a flexible exchange rate system, it is the mechanism by which the values of two nations' monies are determined through supply and demand and by which the exchange of those monies is carried out. The Canadian dollar and the U.S. dollar, the Canadian dollar and the British pound, and the Japanese yen and the British pound are traded in three different foreign exchange markets. Foreign exchange markets involve buyers and sellers all over the world who are linked together by sophisticated communications networks. Application 17.1, “Foreign Exchange Markets,” provides some detail about these markets.

Foreign Exchange Market

A market for the trading of two nations' monies.

APPLICATION 17.1

FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKETS

FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKETS

Foreign exchange markets (known also as forex markets) and the amounts of nations' currencies traded in these markets do not get nearly the media attention that is given to the New York Stock Exchange and stock price movements. This is something of a surprise since, in the aggregate, the market for foreign currencies is the largest in the world. In early 2010, the average daily exchange was over $4 trillion. To put the amount spent on foreign currencies in perspective consider this: In 2010, every person in the world would have had to spend more than $500 per day to match what is spent on trades in foreign exchange markets on a typical day. One reason the daily dollar figures are so big is that in many cases hundreds of millions of dollars are spent on a single trade.

In addition to being big, the markets for foreign currencies are very active. Price quotes on a single currency can change every few seconds. And if the currency is actively traded, the quoted rate might change more than 15,000 times over the course of a day.

Not all currencies are actively traded because there is not as much demand for some currencies as there is for others. In fact, a distinction is made between “hard” and “soft” currencies. Hard currencies are from advanced industrialized countries like the United States, England, European Union members, and Japan. These currencies are widely demanded and easily converted to other currencies. A very large percentage of foreign exchange trades involves the dollar, pound, euro, or yen. Soft currencies are typically from less developed countries. There is not a strong demand for these currencies, partly because various controls might make it difficult to trade them for other currencies.

Foreign exchange markets are best understood as networks of traders. Unlike the New York Stock Exchange, which is a hub through which listed stock transactions flow, there is no central or base location through which foreign currency transactions are made. Rather, trades are done largely—but not only—in the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan.

Because primary trading locations are spread around the world, trade goes on 24 hours a day. A New York trader coming to work in the morning can contact a trader in London, where it is early afternoon, and late in the day a trader in Los Angeles can contact a trader in Japan, where it is early the next day.

Who are the main participants in foreign exchange markets? The largest group is banks and other financial institutions. About two out of three transactions are between banks. There are also intermediaries, called brokers, who conduct trades for banks. While banks can directly deal with one another, sometimes there is a preference to remain anonymous. Going through a broker allows the buyer or seller to keep its identity a secret. Nations' central banks also participate in foreign exchange markets. In the case of these banks, participation might be to support a national economic policy objective. Finally, private businesses and individuals might trade one currency for another in order to expand sales, make an investment, travel, or simply make a purchase.

Based on: “Foreign Currency Exchange,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2001, http://www.ny.frb.org/education/fx/foreign.html; Sam Y. Cross, “All about … the Foreign Exchange Market in the United States,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1998, http://www.ny.frb.org/education/addpub/usfxm; http://www.gocurrency.com/articles/stories-fx-market.htm; Michael R. King and Dagfinn Rime, “The $4 trillion question: what explains FX growth since the 2007 survey?” BIS Quarterly Review, December 2010, pp. 27–40.

Changes in Exchange Rates Since exchange rates are determined by the forces of supply and demand in foreign exchange markets, any factor that causes a change in the supply and/or demand of a nation's currency in one of these markets will cause a change in the currency's exchange rate and the amount traded in that market. For example, referring to Figure 17.3, if the demand for Brazilian reals by those with U.S. dollars increases, the demand curve for reals will shift to the right, causing the dollar price of reals as well as the amount exchanged to increase. At an exchange rate of $0.45 = 1 real in Figure 17.3, $4.50 will buy 10 reals. If, because of an increase in the demand for reals, the exchange rate becomes $0.60 = 1 real, the dollar is worth less compared to the real, and $4.50 will buy only 7.5 reals. Can you graphically determine the results of an increase in supply?1

When an exchange rate changes, the value of one nation's money changes compared to the value of the other nation's money. One becomes worth more compared to the other, and one becomes worth less. Expressions that are heard in the media such as “the declining value of the dollar in world trade” refer to the fact that the exchange rate is changing in favor of other nations' currencies and against the U.S. dollar.

APPLICATION 17.2

DOES A LOWER-VALUED DOLLAR HELP THE ECONOMY?

DOES A LOWER-VALUED DOLLAR HELP THE ECONOMY?

Suppose that over the course of a year the value of the U.S. dollar falls by over 15 percent in relation to the Japanese yen and the Canadian dollar. Since a drop in the value of the dollar on foreign exchange markets effectively puts the U.S. economy on sale, this would make purchases of U.S. goods and services cheaper for these foreign buyers. People with yen or Canadian dollars would be able to buy tuition at U.S. colleges and universities, a trip to Disney World, and even U.S.-manufactured jeans for less of their own money.

At first glance this looks like a good deal for the U.S. economy because a drop in the dollar's value should lead to more spending on U.S.-produced goods and services, which in turn should increase U.S. production and employment. But it just isn't that simple. There are some downsides to a devalued dollar.

While a lower-valued dollar makes U.S. goods cheaper to foreign buyers, it makes imports more expensive for U.S. consumers. A drop in the value of the dollar on foreign exchange markets forces U.S. consumers to pay more for the lumber, automobiles, metals, electronics, and other products they purchase from Canada and Japan, as well as the coffee, bananas, gloves, violins, and other items purchased from other countries.

These changes in the price of exports and imports give rise to important questions that come with the lower-valued dollar. Will we face a problem with demand-pull inflation from more foreign purchases of U.S. goods as well as increased spending on U.S. goods by U.S. consumers who want to avoid the rise in prices of foreign goods? Could there be a problem with cost-push inflation if U.S. firms, having to pay more for imported inputs, are forced to raise prices on their finished products?

We should also consider that a devaluation of the dollar can hurt a vulnerable part of the U.S. population: immigrants who come to the United States to work and support their families living in poverty in their home countries. When the value of the dollar drops, $1,000 sent home exchanges for fewer units of the home money—which means less food, shelter, and other needs for the family.

Based on: Roberto Perez Betancourt, “Devaluation of Dollar Hurts U.S. Consumers,” Radio Habana Cuba, May 4, 2005, http://www.radiohc.cu/ingles/especiales/abril05/especiales05abril.htm.

It is important to understand some of the major factors that cause supply and demand to change and exchange rates to fluctuate in foreign exchange markets, because a change in the value of a nation's currency in international exchange markets can have significant economic consequences. As exchange rates rise and fall, the international prices of a country's goods and services rise and fall as well. For example, when the value of the dollar drops in foreign exchange markets, goods produced in the United States become cheaper for foreign buyers and foreign-made products become more expensive for U.S. buyers. In addition, an increase or decrease in the value of a country's money may discourage or encourage foreign ownership of real assets in the country.

Application 17.2, “Does a Lower-Valued Dollar Help the Economy?”, explores the effect on the U.S. economy when the value of the dollar falls in foreign exchange markets. Because a lower-valued dollar makes U.S. exports cheaper to foreign buyers and foreign imports to the United States more expensive, it is entirely reasonable to presume that it helps the U.S. economy while hurting foreign economies. But Application 17.2 points out that a drop in the dollar's value can, in fact, hurt the U.S. economy.

Factors Influencing Demand and Supply in Foreign Exchange Markets Several factors can cause a change in the demand and/or supply of a nation's money in foreign exchange markets. One important factor that causes the demand for foreign currencies to shift is a change in the taste for foreign products: As a country's products become more popular, demand for that country's money increases, and as they become less popular, demand falls. The demand for foreign-made goods has increased in the United States in recent years. This may be due to real or imagined perceptions of the quality of foreign products, a larger array of foreign goods that are now available, or other factors. Consider, for example, the increased popularity of Australian wines, bike trips through France and Vietnam, and Belgian chocolates.

FIGURE 17.4 Changes in the Demand for and Supply of a Foreign Currency

An increase in the demand for a nation's currency will increase the price of its currency. If an increase in the demand for the currency is matched by an increase in supply, the exchange rate will remain unchanged.

Figure 17.4a illustrates the impact on exchange rates of an increase in the demand for a nation's currency caused by an increase in the demand for its products. Using the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen as an example, an increase in the U.S. demand for Japanese products will increase the demand for yen and shift the demand curve to the right from D1 to D2. This causes the dollar price of yen to rise from P1 to P2 and the value of the dollar to decline. Can this decline in the value of the dollar be stopped?

An increase in the supply of yen could cause the exchange rate to return to its original level. This is shown in Figure 17.4b, where the supply curve shifts to the right from S1 to S2 following the shift in demand from D1 to D2. This increase in the supply of yen could occur if there were an increase in the Japanese demand for U.S. products or investment opportunities: A larger quantity of yen would appear on the market as the Japanese sought dollars to buy U.S. products or invest in U.S. assets.

A second factor that can cause a change in the demand or supply of a nation's currency and its exchange rate is a change in economic conditions in either the demanding or supplying country. Consider the effect of inflation on the demand for Canadian dollars by U.S. importers and investors. If the inflation occurs in the United States, it will make the price tags on Canadian goods relatively lower for U.S. importers and investors, thereby causing the U.S. demand curve for Canadian dollars to increase, or shift to the right. As a result, the price of Canadian dollars will rise, as will the number of Canadian dollars exchanged. If the inflation occurs in Canada, it will make the cost of Canadian goods relatively higher for U.S. investors and importers and lead to a decrease, or leftward shift, in the demand curve for Canadian dollars. As a result, the price of Canadian dollars will fall and so will the amount exchanged.

A third factor that influences exchange rates is the rate of interest that can be earned on securities issued by private and government borrowers in different countries. If investment opportunities in another country yield a higher return than is available domestically, some individuals and corporations with global investment strategies will want to purchase the higher-yielding foreign securities. To do so increases the demand for the currency of the nation with the higher interest rates, thereby causing a change in its exchange rate. The increased buying and selling of financial instruments on a global level in recent years has had an important effect on exchange rate determination.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

CHANGES IN EXCHANGE RATES

CHANGES IN EXCHANGE RATES

Each of the following hypothetical situations could affect the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and another country's money. For each situation, indicate how supply or demand and the equilibrium price and quantity in that particular foreign exchange market would change and whether the value of the U.S. dollar would rise or fall in that market.

- A report is issued that certain wines produced in Argentina could contain chemicals that are harmful to a person's health. As a result, the U.S. demand for pesos would ______, the dollar price of pesos would _______, the equilibrium quantity of dollars traded for pesos would ______, and the value of the dollar in relation to the peso would _______.

- Rates of interest in the United States move above rates in Britain. As a result, the supply of British pounds to the United States would ______, the dollar price of pounds would ______, the equilibrium quantity of pounds traded for dollars would ______, and the value of the dollar in relation to the pound would _______.

- Japan introduces a newly designed hybrid car that is an immediate hit with U.S. automobile buyers. As a result, the U.S. demand for Japanese yen would ______, the dollar price of yen would ______, the equilibrium quantity of dollars traded for yen would ______, and the value of the dollar in relation to the yen would ______.

- The rate of inflation in the United States rises above the rate of inflation in Switzerland. As a result, the supply of Swiss francs to the United States would ______, the dollar price of francs would ______, the equilibrium quantity of francs traded for dollars would ____, and the value of the dollar in relation to the Swiss franc would ____.

- More U.S. citizens travel to Israel as airlines offer substantial discounts on fares. As a result, the U.S. demand for shekels would ____, the dollar price of shekels would ____, the equilibrium quantity of dollars traded for shekels would ____, and the value of the dollar in relation to the shekel would ______.

- Political unrest develops in Bahrain. As a result, the U.S. demand for Bahrain dinars would ______, the supply of dinars to the United States would ______, the dollar price of dinars would ______, the equilibrium quantity of dinars traded for dollars would ____, and the value of the dollar in relation to the dinar would ____.

Answers can be found at the back of the book.

Fourth, the supply and demand of a nation's money in foreign exchange markets may be influenced by government and central bank policies. For example, in an effort to keep the value of a country's money from falling, its government or central bank might intervene in a foreign exchange market to restrict the supply of its currency. Government intervention in foreign exchange markets occurs from time to time, despite the fact that they are considered to be basically free markets.

Changes in exchange rates will also cause buyers and sellers of foreign currencies to enter or leave the market if they regard foreign goods, services, and assets as substitutes for domestic items. For example, when the value of the peso falls, travel to Mexico by residents of the United States becomes a desirable alternative to travel at home. This increase in foreign travel, considered by itself, would cause the demand curve for pesos to shift to the right and the value of the peso to increase. Finally, other factors such as political climates, expectations, and trade restrictions can cause the demand and/or supply curves for a nation's money to shift and the exchange rate to change. Test Your Understanding, “Changes in Exchange Rates,” lets you practice evaluating how changes in economic and noneconomic conditions in two countries would affect exchange rates between their monies.

TABLE 17.2 U.S. International Financial Transactions

The current account records payment flows for goods, services, gifts, and the like; the capital account records payments for financial and real assets.

Source: Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), pp. 436–437.

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS AND BALANCES

A wide variety of international transactions requires payment flows from one country to another. These include importing and exporting goods and services, buying and selling foreign financial instruments and real assets, military and foreign assistance, gifts, grants, and travel. Some of these transactions involve major outlays for real estate, production equipment, and corporate stock; some involve small sums for gifts to relatives back home.

To analyze the many and varied types of financial transactions that occur between the United States and other nations, these transactions are grouped into major categories. Through the use of these categories, the accounting process for international transactions is simplified and, more importantly, transactions that could cause problems for the economy can be more readily identified. The two major transactions categories are the current account and the capital account.

The Current Account

The current account records payments for exports and imports of goods; payments for military transactions, foreign travel, transportation, and other services; income from investments; and unilateral transfers (gifts). The major components of the current account and their dollar values for 2010 are shown at the top of Table 17.2. In presenting these figures, dollar payment outflows to other countries are indicated by negative numbers and dollar payment inflows from other countries by positive numbers. For example, the value of U.S. exports of merchandise (goods) in 2010 was almost $1.3 trillion, a positive number because exports bring payment inflows, while the value of imports of merchandise in 2010 was −$1.93 trillion, a negative number because dollars flow out when foreign goods are purchased. When merchandise imports are subtracted from exports, a net figure called the balance of trade results. In 2010, the balance of trade was −$645.9 billion, indicating that U.S. buyers purchased $645.9 billion more foreign goods than foreign buyers bought U.S. goods.2

Current Account

A category of international transactions that records figures for exports and imports of merchandise, services, unilateral transfers, and other foreign dealings.

Balance of Trade

The figure that results when merchandise imports are subtracted from exports.

FIGURE 17.5 U.S. Balance of Trade: 1970–2010

Since the mid-1970s, and especially since the late-1990s, the United States has run significant balance of trade deficits as the value of merchandise imports has exceeded the value of exports.

Source: Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), p. 436.

The balance of trade is significant because it involves a large flow of money, reflects the results of a nation's international trade activity, and is frequently cited in studies and discussions of international transactions. When the value of a country's exports of goods is greater than the value of its imports, a balance of trade surplus occurs; when the value of a country's imports of goods is greater than the value of its exports, a balance of trade deficit arises.

Balance of Trade Surplus (Deficit)

The value of a country's merchandise exports is greater (less) than the value of its imports.

Figure 17.5 charts the annual balance of trade for the United States from 1970 through 2010. In recent decades, sizable trade deficits have occurred, especially after the late-1990s, and the trade deficit has become so large that it is a matter of concern. Factors such as the popularity of foreign goods like automobiles and home electronics equipment, the availability of inexpensive shoes and clothing, strong foreign rivals in markets for U.S. export products, the rise in the price of oil, and changes in the value of the dollar have contributed to the significant deficits of recent years.

The dollar figures for the other current account classifications in Table 17.2 are given as net amounts; that is, unlike merchandise exports and imports, the payment outflows have already been subtracted from the inflows and are not given separately. For example, on net services, more payment inflows than outflows occurred, resulting in a net figure of $145.8 billion. On the other hand, the unilateral transfer number of −$136.1 billion indicates that, for that category, more payments flowed out of than into the United States.

The balance of trade, net services, net income, and unilateral transfers are added together to arrive at the current account balance, which was −$470.9 billion in 2010. This figure means that transactions from the current account components caused 470.9 billion more U.S. dollars to flow out for payments than the value of money that flowed in. This is referred to as a current account deficit. Had the figure been a positive number, there would have been a current account surplus.

Current Account Deficit (Surplus)

A negative (positive) figure results when all current account transactions are added together.

Application 17.3, “A Prized Export,” looks at one group of expenditures that positively impacts the current account: the spending by foreign students getting an education and earning degrees at colleges and universities in the United States.

APPLICATION 17.3

A PRIZED EXPORT

A PRIZED EXPORT

When people think about what it is that the United States exports, items like aircraft, farm machinery, soybeans, and even California wine come to mind. But they don't often think about a growing and prized export: an education and degree from a college or university located in the United States. At first glance, an education for a foreign student in the United States may not appear to be an export, but it clearly brings foreign spending on a U.S. product.

There are and have been a number of U.S. universities that have campuses “abroad,” like Boston College's campus in Brussels, Belgium, and St. Louis-based Webster University's campuses in seven countries, which serve both U.S. and foreign students. While these offer students the opportunities to experience another culture, it is the actual arrival and study of foreign students on campuses located in the U.S. that serve as the true export.

The number of foreign students now attending colleges and universities in the United States is significant. The Institute of International Education reported that 723,277 attended during the 2010–2011 academic year. An appreciation for the size of this number can be gained from a comment by Michael K. Young, President of the University of Washington, who noted that in 2012 there were more foreign students in the state of Washington than there were students from the other 49 states.

Where are the home countries of foreign students coming to the United States? In 2011, the largest group of students—157,558—came from China, followed by students from South Korea, India, Canada, and Taiwan. Together the students from these five countries accounted for more than fifty percent of the foreign students in the United States.

How does the education of all of these foreign students affect international finance and the balance of payments for the United States? Like anyone who wants to purchase an item in another country, “home” money must be converted to the currency of the country in which the item is purchased. So, all of the foreign students purchasing tuition, books, fast food, and more in the United States need to convert their home currency from China, India, and elsewhere to U.S. dollars in foreign exchange markets. This is no different from the buyer of U.S. farm machinery or soybeans who must also convert home currency to U.S. dollars to make the purchases.

The Institute of International Education reported that foreign students contribute about $21 billion per year to the U.S. economy through their payments for tuition, living expenses, transportation, and other expenditures. These sizeable expenditures help to add a positive number to the U.S. current account by increasing exports which helps to counter the outflow of dollars for spending on imports.

While the education and degree seeking expenditures for an education in the United States by a foreign student may not be thought of as an “export” since no good or service leaves the country, the service each student receives behaves like an export. Perhaps there should be a deeper appreciation for the U.S. higher education system and it should be regarded as something in which the United States has a strong comparative advantage. We may not obviously recognize the value of one of our most desirable and prized U.S. products.

Based on: Mary Beth Marklein, “More foreign students studying in USA,” USA Today, November 13, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/education/story/2011-11-13/foreign-students-boost-usa-economy/51188560/1; Tamar Lewin, “Taking More Seats on Campus, Foreigners Also Pay the Freight,” The New York Times, February 4, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/education/international-students-pay-top-dollar-at-us-colleges.html.

The Capital Account

The capital account, which is listed in the lower part of Table 17.2, records payment flows for investment purchases such as stocks, bonds, government securities, and real estate. When U.S. individuals, businesses, and governments buy foreign-owned financial or real assets, there are payment flows from the United States. These flows are recorded in the capital account component “U.S. assets abroad, net” as negative numbers since payments are flowing out of the country. When corporate financial instruments, government securities, and real estate owned by U.S. entities are purchased by foreign buyers, there are payment flows to the United States. These are recorded in the capital account component “Foreign assets in the United States, net” as positive numbers, indicating payment inflows.

Capital Account

A category of international transactions that records the purchase and sale of financial and real assets between the United States and other nations.

In Table 17.2, the capital account balance for 2010 is $254.1 billion, a positive number indicating that there was more foreign investment in U.S. assets than U.S. investment in foreign assets during that year. This positive number in the capital account makes sense in light of the large negative current account balance listed in Table 17.2. The large demand by U.S. buyers for imports was not offset by an equal foreign demand for U.S. exports. As the dollar became cheaper for foreigners to purchase, U.S. financial and real assets became less expensive and more attractive to these buyers.

Balancing the Accounts

In recording these payment inflows and outflows, there should be a balance: The dollars used to purchase foreign goods, assets, and the like should be matched by an equal amount of foreign currency flowing into the dollar exchange markets to accommodate those purchases. As a result, the current account balance and the capital account balance together should total zero. However, because of the volume of money traded and the diversity of locations and customs in foreign exchange markets, the accounting for these transactions may not be completely accurate. To make payment inflows and outflows equal, the government adds an amount for statistical discrepancies to its accounting process. This is given at the bottom of Table 17.2 and, when added to the balances for the two major transactions categories, results in a zero balance in the very last line.

CHALLENGES TO THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL SYSTEM

The globalization of economic activity has created both opportunities and challenges for the international financial system. Two challenges have been particularly important: the debt issues faced by a number of countries as a result of large-scale borrowing from foreign lenders, and efforts to integrate the monetary systems of the countries in the European Union.

External Debt Issues

One important type of international financial transaction included in the capital account is loan making. Many governments and businesses, including those in developing nations, borrow from lenders, such as banks, governments, and individuals, in other countries to help finance investments and other activities. For example, a U.S. bank could lend money to the government of Brazil, a South African could buy U.S. Treasury bonds, or Canadian and U.S. investors could buy corporate bonds in companies of each other's countries. This type of borrowing results in external debt because it is owed to lenders outside of, or external to, the borrowing country.

External Debt

Money owed by borrowers in one country to lenders in other countries.

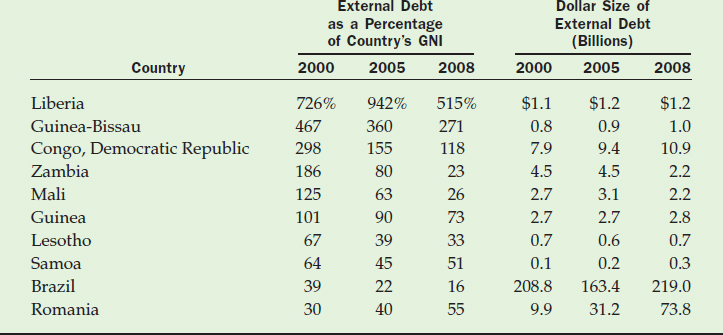

TABLE 17.3 External Debt of Selected Highly Indebted Developing Countries

Some countries have an external debt that is much greater than the country's national income.

Source: World Bank, Global Development Finance: External Debt of Developing Countries (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2010), pp. 74–75, 100–101, 138–139, 140–141, 170–171, 172–173, 186–187, 228–229, 234–235, 296–297.

External debt has been a mounting problem for some developing countries. In 2008, the total external debt outstanding in developing countries exceeded $3.7 trillion.3 The external debt of some developing nations has become so large that they are unable to repay the interest on their loans, much less the loans themselves.

The magnitude of the external debt problem is illustrated in Table 17.3, which ranks several highly indebted developing countries according to the amount each owed to foreign lenders as a percentage of that country's gross national income (GNI) in 2000, 2005, and 2008.4 Also shown is the size of each country's external debt, measured in U.S. dollars. While Liberia is among those with the highest debt as a percentage of GNI, the dollar size of its external debt was relatively small. Brazil, on the other hand, had one of the smallest external debts, when compared to GNI, but in dollar terms it was the most indebted country in the table.

The Opportunity Cost of External Debt There are substantial opportunity costs for borrowing nations that seek to service and repay their large external debts and substantial opportunity costs for lending nations if they do not.

To honor their financial obligations to foreign lenders, borrowing nations must cut back on spending by their households, businesses, and governments in order to send money to their debt holders. (This is the same situation that a family faces when it falls deeply into debt: It must cut back on current consumption in order to pay lenders.) In developing nations where incomes are low, the harsh austerity measures needed to cut back spending to repay the debt may not be tolerable or even possible. In addition, payment of a debt of this magnitude causes the postponement of spending on investment goods, which hampers future economic growth. In short, the opportunity cost of repayment is substantial: The decline in current spending could send the economy into a recession, making payments even more difficult and sacrificing future economic growth. To these economic costs can be added the political unrest that could well result from such serious economic disruptions.

Failure by developing countries to meet external debt interest payments or repay loan principals in a timely manner creates problems for lending institutions, especially commercial banks. When countries can no longer meet their loan obligations, millions of dollars of interest income are at risk for these banks, in addition to possible default on the principal. The unacceptably high risk associated with loan making to developing countries has reduced the flow of funds from banks to these countries. In 1980, before the external debt crisis, commercial banks accounted for about 30 percent of the debt to developing countries. By 2005 those same banks accounted for about 7.6 percent of that debt to developing countries.5

Dealing with External Debt Issues An early attempt to alleviate an external debt crisis was the Brady Plan. This 1989 proposal, which was used in several countries, aimed to restructure and reduce the debts owed to commercial banks by developing countries, provided the countries implemented policies to strengthen their economies.6 In 1996 the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, in conjunction with several governments and international financial organizations, launched the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative to ease the external debt burden of highly indebted developing countries that carried out economic reforms to improve educational attainment, health care, and other social conditions. Prior to the Initiative, eligible countries were spending more on debt service than on health and education. By 2004 they were spending almost four times as much on health, education, and other social services than on debt service. By 2008, 33 countries had been approved for debt reduction under the HIPC Initiative.7

Brady Plan

A proposal to restructure and reduce developing country indebtedness to commercial banks.

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative

A joint initiative by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to help heavily indebted developing countries manage their external debts.

Table 7.3 shows that there have been some successes in dealing with the debt crisis. Zambia's external debt dropped from 186 percent to 23 percent of GNI from 2000 through 2008. Other countries, such as Mali, experienced significant decreases in debt as a percentage of GNI as well. But Table 17.3 also shows that the debt crisis is far from solved for other countries.

Monetary Integration in Europe

As indicated in Chapter 16, an important development in the 1980s and 1990s was the formation of the European Community (EC), which later became the European Union (EU), a single trading entity larger in population and economic size than the United States. Most of the countries that comprise this large and closely knit trading bloc integrated their monetary systems in 2002.

The first step toward monetary integration occurred in 1979, when the European Monetary System, or EMS, was formed to limit the variability of exchange rates between European nations' currencies. Rates were aligned using a mechanism that allowed exchange rates to fluctuate by only a small percentage around a central value. The German mark was the keystone currency on which the EMS was built.

European Monetary System (EMS)

An agreement to limit the variability of exchange rates between European nations' currencies.

UP FOR DEBATE

EURO-DREAMS

EURO-DREAMS

Issue Imagine the place in history that awaits the person who persuaded the leaders of nations whose past relations were largely uneasy alliances or hostilities that sometimes degenerated into all-out war to come together, abandon their sovereign currencies and the autonomy of their central banks, and accept a common currency called the euro. Is the dream of a single currency circulating among the member countries of the European Union realistic in the long term?

Yes It is realistic to expect the countries of the European Union to accept the euro. The world that European nations face today is vastly different from the world where European relations were marked by distrust and highly focused nationalism. With economic activity crossing national borders on a huge scale, countries that want to be an “island fortress” insulated against all outside interests are painfully out-of-step with the times. By acting as one economic unit rather than separately, European nations will be better able to specialize and flex their muscle in the global arena. Surely it is obvious to the leaders in Europe's capitals that if they are to join together and seek a common outcome, their solidarity will be enhanced by adopting a common currency.

No It is not realistic to expect the countries of the European Union to wholeheartedly accept the euro. Centuries of deep and abiding nationalism cannot be erased with the stroke of a pen. The unified monetary system may well surpass expectations—until a serious crisis occurs. When this happens, member countries may be slow to support policies that benefit the EU and stabilize the euro at the expense of national objectives. Further, even if the countries are willing to act as one and put EU interests above national interests, the fact is they face different problems that may require conflicting responses, not a single central bank policy. Finally, should we really expect member countries to always be willing and able to follow stringent government tax and expenditure policies in order to stabilize the euro?

The next major step toward monetary unification was the Maastricht Treaty of 1991, which was ratified by the EC members in 1993. Under the terms of the treaty the EMS would be replaced by an Economic and Monetary Union, or EMU, and there would be a common currency and a European Central Bank to oversee a single monetary policy for the member countries. The Maastricht Treaty, in effect, called for a fixed exchange rate system to apply to member countries' currencies.8

Maastricht Treaty

Called for a common currency and central bank to oversee a single monetary policy for countries belonging to Europe's Economic and Monetary Union.

In 1999 a monetary union of 11 countries occurred, and the euro, a common European currency, was launched. By 2002 the euro replaced the currencies of most EU member countries, and this became the world's largest currency transformation. With time, new countries have joined the EU, and some have adopted the euro. In countries that held out on adopting the euro, like Poland, the financial crisis of late 2008 and 2009 prompted a new look.9

From the beginning there were supporters and skeptics of this union, and many concerns—either real or perceived. One concern has been that as the member countries experience different economic problems, a single monetary policy may not be able to address all of their needs at one time. One country might face inflation while another faces unemployment, leading to advocacy for different types of economic policies to follow. Furthermore, some of the smaller countries in the EU may have less capacity to strengthen their economies in a time of severe economic conditions, and they may feel that their economies are of less concern than those of the larger, more powerful members.

The mobility of resources and protection of tradition are other issues. Because of differences in language and tradition, Europeans are less mobile than individuals in the United States. It may be more difficult to relocate from Copenhagen with its Danish language to Madrid with its Spanish language than it would be from Seattle to Boston. The strong attachment to culture and tradition can also be extended to the currency in many countries. There are stories of small towns and villages that have clung to their native currency rather than adopt the Euro.

With just a decade and a half or so of experience with the euro, time will tell whether the original intentions of the EU and the euro, such as improved trade among euro countries, are successful. Up for Debate, “Euro-Dreams,” takes a look at some of the arguments for and against the continued success of the euro. What do you think will be the long-term reality of the euro?

Summary

- An exchange rate is the number of units of one country's money that is equal to one unit of another country's money. In the past, exchange rates were often fixed, or tied to the value of the gold backing a country's money. When the gold backing was reduced, devaluation occurred.

- Most exchange rates are flexible and continually changing because they are determined by supply and demand. The demand curve for a country's money by those holding another country's money is downward sloping, and the supply curve for a country's money is upward sloping.

- Foreign exchange markets are the mechanisms through which the monies of different nations are traded and exchange rates are determined. When an exchange rate between two nations' monies changes, one nation's money becomes worth more in terms of the other nation's money. Changes in exchange rates affect economic conditions through their effects on the prices of exports, imports, and financial and real assets.

- Any factor that causes demand and/or supply in a foreign exchange market to change will alter the exchange rate, as well as the amount of money traded. Some important factors affecting the demand for and/or supply of a foreign money include the popularity of imports and exports, economic conditions in either the importing or exporting nation, interest rates that can be earned on investments in other countries, and intervention in foreign exchange markets by governments or central banks.

- All international transactions that cause payment outflows or inflows are of economic importance. For accounting and analysis purposes, these transactions are placed into different categories, the most important of which are the current account and the capital account.

- The current account includes the balance of trade, as well as figures for investment income, unilateral transfers, and the like. When the U.S. current account balance is a negative number, more dollars have flowed out of the United States than foreign payments have flowed in, and a current account deficit exists. When the current account balance is a positive number, more foreign payments have flowed in than dollars have flowed out, resulting in a current account surplus. In recent years, substantial balance of trade deficits have contributed to negative current account balances and caused serious concern in the United States.

- The capital account records payment flows for financial and real assets. It has a positive balance when more money flows into the United States for stocks, bonds, real estate, and other assets than flows out for foreign assets. A positive capital account balance may be the result of a negative current account balance. The categorizing of international payments also includes a figure for statistical discrepancy that allows all payments to balance.

- Several nations have accumulated large external debts that may be beyond their abilities to repay. External debt presents problems for both lending and borrowing countries. Significant opportunity costs exist whether the debt is repaid or not, and actions have been taken to reduce many developing countries' external debts.

- Most nations in the European Union have integrated their currencies. There are ongoing questions about the costs and benefits of having several nations use a single, common currency.

Key Terms and Concepts

Exchange rate

Fixed exchange rates

Devaluation

Flexible (floating) exchange rates

Foreign exchange market

Exchange rate determination

Current account

Balance of trade

Balance of trade surplus (deficit)

Current account deficit (surplus)

Capital account

External debt

Brady Plan

Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative

European Monetary System (EMS)

Maastricht Treaty

Review Questions

- Would the value of the dollar, compared to the Swiss franc, increase or decrease if the exchange rate went from 1.3 francs = $1.00 to 1.2 francs = $1.00? Why?

- Explain why devaluation of a nation's currency could increase the demand for that nation's exports and decrease the demand by that nation for imports.

- Why is the demand curve for a nation's money in a foreign exchange market downward sloping, and why is the supply curve upward sloping?

- Illustrate graphically how the exchange rate for a nation's money is determined in a flexible exchange rate system, and show how the rate would be affected by an increase and a decrease in demand and by an increase and a decrease in supply.

- How would each of the following transactions affect payment flows into or out of the United States, and into which major transactions category would each transaction be classified?

- The purchase of U.S. Treasury securities by a Canadian bank

- The sale of U.S. grain to China

- A gift of cash from a family in Pennsylvania to relatives in Poland

- The purchase of a condo in Paris by a family in New York

- The purchase of stock in an Indonesian company by an economics professor in Chicago

- A student from Indonesia comes to study at a university in St. Louis

- What are the major components of the current account, and what is the capital account? Give some examples of international transactions that would cause positive and negative dollar amounts to register in the current account.

- What is an external debt and what opportunity costs does its repayment impose on a highly indebted country?

- Summarize the steps Europeans have taken toward a monetary union. What problems could stand in the way of sustaining that union in the long run?

Discussion Questions

- Locate a recent listing of foreign exchange rates. Compare the recent rates with those given in Table 17.1. Are there any instances in which the rate has changed substantially? If so, give your opinion as to what factors might have caused such a change.

- Answer each of the following.

- How many Japanese yen would have to be converted to dollars for a person in Japan to purchase a $40,000 U.S. SUV if the exchange rate were 125 yen = $1.00?

- How many yen would have to be converted to dollars to purchase the $40,000 SUV after the exchange rate changed to 110 yen = $1.00?

- How many dollars would have to be converted to yen for a person in Los Angeles to purchase a 4,000,000-yen Japanese automobile if the exchange rate were 125 yen = $1.00?

- How many dollars would have to be converted to yen to purchase the 4,000,000-yen auto after the exchange rate changed to 110 yen = $1.00?

- What are some advantages and disadvantages of a fixed exchange rate system and of a flexible exchange rate system?

- Explain how each of the following developments, taken alone, would affect the value of the dollar. Use supply and demand analysis in your answer.

- The perception in other countries that the quality of goods produced in the United States is improving

- A large federal government budget deficit that raises interest rates in the United States

- Intervention by the Federal Reserve in foreign exchange markets that results in dollars moving into those markets

- A poor harvest in most of the grain-producing countries of the world except the United States

- The expectation of war among several African countries

- The United States has primarily experienced balance of trade deficits since the late 1970s and serious deficits since the late 1990s. What could be the short-term and long-term effects if this condition persists? What policy actions would you recommend to reverse this trend?

- Why would a current account deficit lead to a capital account surplus?

- What problems would arise if a developing country defaulted on its external debt? Who would be hurt? What policies would you recommend to ease external debt problems, and what would be the effects of these policies on borrowing countries?

- Do you expect that in the long term the euro will be successful as a currency?

Critical Thinking Case 17

HELPING POOR COUNTRIES

Critical Thinking Skills

Examining cause-and-effect relationships

Identifying criteria for appropriate policies

Economic Concepts

External debt

Balance of payments

The IMF provides low-income countries with policy advice, technical assistance, and financial support. Low-income countries receive more than half of the technical assistance provided by the Fund, and financial support is extended at low interest rates and over relatively long time horizons. Low-income countries with high external debt burdens are also eligible for debt relief.

Despite progress in recent decades, the extreme poverty prevalent in low-income countries is a critical problem facing the global community. At present, more than a billion people are living on less than $1 a day. More than three-quarters of a billion people are malnourished—about a fifth of them children. One-hundred and sixteen of every 1,000 children born in low-income countries die before reaching the age of five, the majority from malnutrition or disease that is readily preventable in high-income countries.

[The United Nations has set goals] centered on halving poverty between 1990 and 2015. There is little dispute that a sustained, rapid rate of growth in average per capita incomes is essential for meaningful poverty reduction. The factors that have been shown to promote such growth include openness to international trade, sound economic policies, strong institutions and legal frameworks, and good governance.

[In March 2002 strategies were adopted to meet the United Nations' goals.] The first is the pursuit of sound policies and good governance by the low-income countries themselves. The second is larger and more effective international support, including official development assistance and opening markets to developing country exports.

The IMF is helping low-income countries make progress [toward these goals] through each of the Fund's three key functions—lending, technical assistance, and surveillance.

Questions

- How might a loan by the IMF to help a developing country meet its obligations to foreign lenders reduce malnutrition, illness, and premature death among its population?

- The IMF requires that in order to get IMF aid, developing countries accept technical assistance to help manage their economic affairs and surveillance of some policies. Is this an appropriate intrusion into how those countries manage their affairs?

- What criteria would you recommend for determining whether a country qualifies for financial support by the IMF?

Source: International Monetary Fund, “How the IMF Helps Poor Countries,” October 2007, http://www.imf.org/External/np/exr/facts/poor.htm.

1 The supply curve of reals will shift to the right, causing the dollar price of reals to fall and the amount exchanged to rise.

2 Be careful to notice that the term balance of trade is different from the term net exports, which was discussed in Chapter 5. The balance of trade is calculated on the basis of exports and imports of goods, whereas net exports uses both goods and services. Net exports of goods and services is given as a separate component in Table 17.2.

3 The World Bank, Global Development Finance: External Debt of Developing Countries (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2010), p. 24.

4 Gross national income (GNI) is equal to the total value added by all producers in the country, product taxes that were not included in output evaluation, and primary income to the country from abroad.

5 The World Bank, Global Development Finance (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2004), Vol. II, p. 3; (2007), vol. II, p. 3.

6 See John Clark and Elliot Kalter, “Recent Innovations in Debt Restructuring,” Finance & Development, September 1992, p. 6; William R. Rhodes, “The Disaster That Didn't Happen,” The Economist, September 12, 1992, pp. 22–23.

7 International Monetary Fund, “Debt Relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative,” October 2008, http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/hipc.htm.

8 Craig R. Whitney, “Worry over the Euro Sweeps Europe,” The New York Times, April 19, 1997, p. 4.

9 Carter Dougherty, “Some Nations That Spurned the Euro Reconsider,” The New York Times, December 2, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com; Jeffrey Frankel, Harvard Kennedy School Fellow, “The Euro at Ten: Time to Assess,” The New York Times, Times Topics, January 22, 2009, http://topics.blogs.nytimes.com.