CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To present an overview of U.S. international trade by highlighting major U.S. exports and imports as well as major U.S. trading partners.

To explain the principle of comparative advantage.

To define free trade and explore some arguments in its favor.

To define protectionism, explore some arguments in its favor, and introduce the main tools for restricting trade.

To discuss possible trade policies and examine some key trade agreements.

Economic activity is highly globalized. In today's world, it is not unusual to hop a plane to do business in Singapore; for a middle-level corporate manager to work closely with subsidiaries around the world; or to furnish our homes with rugs, art, and furniture from Africa, South America, or Asia. One way to quickly see how globalized economic activity has become is to open your closet and scan the labels on your clothes showing where they were manufactured.

International economics is about the movement of goods and services as well as financial transactions among nations. Medical and disaster aid, military activity, overseas investments, and the import and export of goods such as oil, wine, grain, and automobiles are all relevant to international economics.

This chapter introduces some important topics that relate to international trade, or the movement of goods and services between nations. It begins with an overview of U.S. international trade, including major traded products and important trading partners. Comparative advantage, a basic theory that underlies international trade, the great debate in international economics over free trade versus protectionism, trade policies for stimulating exports, and important agreements affecting trade among nations are then covered. Chapter 17 deals with the financial aspects of international economics.

Trade and financial relationships among nations are growing in importance as the world becomes more globally connected, or “flatter.” These relationships affect jobs available to us, our national security, international relations, and social understanding. Today we are much more aware of the conditions in which people in many countries work, the use of child labor, and the degree to which AIDS and lack of access to safe drinking water are world problems.

AN OVERVIEW OF U.S. INTERNATIONAL TRADE

An important aspect of international economics is international trade: the buying and selling of goods and services among different countries. International trade affects the availability of goods and services as well as the levels of production, employment, and prices in the trading countries. Sales in overseas markets can increase employment among a nation's workers. But international trade can also bring in strong foreign competitors and lead to a drop in sales for a nation's business, which in turn could lower production and employment for the nation. Also, the presence of foreign goods in a market increases competition, which in turn influences product prices. And for a country that is dependent on a major foreign product, increases in the price of that product can influence the country's inflation rate.

International Trade

The buying and selling of goods and services among different countries.

The Size and Composition of U.S. Trade

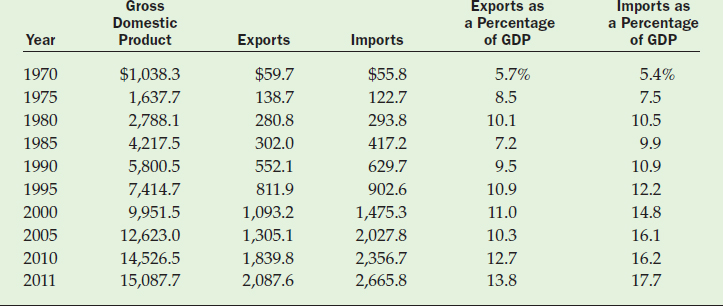

The Size of U.S. Trade The importance of international trade to the U.S. economy is illustrated in Table 16.1, which lists data on exports and imports of goods and services for selected years. The middle columns, Exports and Imports, show that in recent years U.S. export and import transactions have each resulted in the movement of over a trillion dollars in goods and services annually. For example, in 2011 exports and imports amounted to approximately $2.1 and $2.7 trillion, respectively. Notice also that, not surprisingly, the dollar values of exports and imports have grown over the years.

Export

A good or service sold abroad.

Import

A good or service purchased from abroad.

The last two columns of Table 16.1 list exports and imports of goods and services as percentages of gross domestic product (GDP) for each of the selected years. Notice that both exports and imports have generally grown in relative importance when compared to GDP. In 1970 exports were 5.7 percent and imports were 5.4 percent of GDP. By 2011 exports were 13.8 percent of GDP and imports were 17.7 percent. One can conclude from Table 16.1 that foreign trade has become an increasingly important part of the U.S. economy over the years. Notice also the increasing difference between exports and imports as a percentage of GDP.

TABLE 16.1 U.S. Exports and Imports of Goods and Services (Billions of Dollars)

Both the dollar amount of exports and imports, and exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, have increased over the years.

Source: Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), pp. 316–317. The figures for 2011 are preliminary.

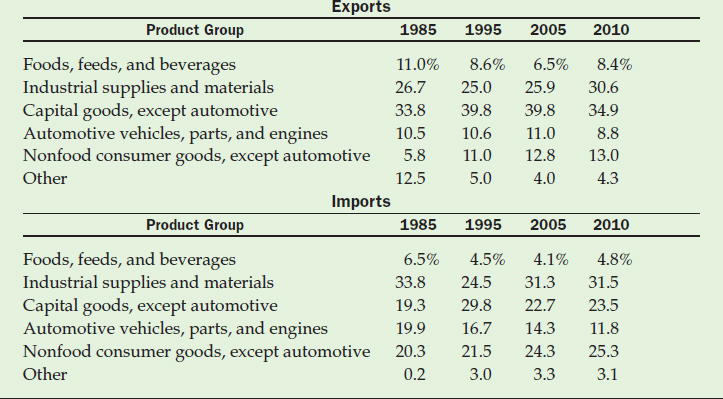

The Composition of U.S. Trade What types of goods and services does the United States export and import? Table 16.2 gives the distribution of U.S. merchandise exports and imports by broad product group for selected years. A broad product group is composed of several related types of goods. For example, the foods, feeds, and beverages group includes grains, meat products, vegetables, fish, and wine.1

The upper half of the table shows that the most important class of exports has been capital goods, followed by industrial supplies and materials. The capital goods category includes products ranging from oil drilling and metalworking machinery to hospital equipment and civilian aircraft. Industrial supplies and materials includes such things as iron and steel products, fuels and petroleum products, and building materials.2

Imports by broad product group are shown in the lower half of Table 16.2. The table shows that capital goods grew and then declined in importance over the period while industrial supplies and materials decreased and then rose in importance. More specific significant imports to the United States in recent years have been electrical machinery, televisions and related electronics, data equipment, crude oil, vehicles, chemicals, and clothing.3 Notice that capital goods and industrial supplies and materials are important both as exports and imports. Why do you think this is the case? Does it suggest something about what is traded or with whom we trade?

TABLE 16.2 Percentage Distribution of U.S. Merchandise Exports and Imports by Broad Product Categories

U.S. exporting and importing activity primarily involves capital goods and industrial supplies and materials.

Source: Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), p. 440.

One important fact that Table 16.2 conveys is that the relative importance of goods and services in international trade changes over time. For example, in 1985 exports of foods, feeds, and beverages were about twice as large as exports of nonfood consumer goods. In 2010, exports of nonfood consumer goods were substantially larger—by 50 percent—than exports of foods, feeds, and beverages. Obviously, things change over time.

The Geographic Distribution of U.S. Trade The percentages of U.S. exports to and imports from major U.S. trading partners in 2011 are given in Table 16.3. The majority of U.S. trade is with developed nations in North America, Europe, and Asia, although trade with less developed nations has grown in relative importance over the years.

In terms of specific countries, Canada, Mexico, China, and Japan are the four most important trading partners of the United States. However, several of the other countries listed in the table are part of the European Union, or EU. The 27 member countries of the EU are joined into a single market area and, in many ways, act like a single trading partner. The United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Netherlands, Ireland, and Belgium—all listed on the table—are part of the EU. As a unit, the EU is a leading exporter and importer.4

TABLE 16.3 United States' Fifteen Largest Export and Import Trading Partners in 2011

Most of the largest trading partners with the United States are developed nations in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Top Trading Partners – Total Trade, Exports, Imports, Year-to-Date December 2011,” http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/top/top1112.html.

As the globalization of trade expands, more buyers of shoes, shirts, electronics, pharmaceutical drugs, vitamins, food, and other products are becoming aware of another side of importing low-cost goods to the United States. It has become clear that safety, quality, and labor standards adopted by the United States are not being applied in many cases by foreign producers. In recent years, we have been faced with a pet food scare due to contaminants in ingredients, lead in toys and other consumer products, impurities in drugs, and the use of child labor in many of the factories that produce these cheap goods. Application 16.1, “A Sad Story,” deals with one case where a retailer, Gap, discovered the use of child labor in a factory subcontracted through one of its vendors.

APPLICATION 16.1

A SAD STORY

A SAD STORY

More and more, goods and services sold by U.S. companies are produced outside of the United States: from Nike shoes produced in factories around the world to help with your computer problems from a technician in India. But as foreign-produced goods account for more of our purchases, there is growing concern over the working conditions endured by many of those producing these goods. When reading about these conditions, one frequently comes across terms such as sweatshop and human trafficking.

In 2007, the clothing retailer Gap found that one of its products—some hand-stitched blouses—was being sewn by child labor in a New Delhi, India, sweatshop with squalid conditions. A British newspaper reported that some of the children were as young as 10, worked for 16 hours a day, and were punished with hits from a rubber pipe or by having oily rags stuffed in their mouths.

One young boy said, “I was bought from my parents' village in [the northern state of] Bihar and taken to New Delhi by train. The men came looking for us in July. They had loudspeakers in the back of a car and told my parents that if they sent me to work in the city, they won't have to work in the farms. My father was paid a fee for me, and I was brought down with 40 other children.”

U.S. companies that subcontract work to foreign vendors have tried to monitor operations. In this case, the work was further subcontracted in violation of Gap's policies.

Gap was obviously embarrassed, and its response to this situation was immediate. It promised that none of the garments would ever be sold, ensured that the children were cared for and reunited with their families, reduced the contract of the vendor responsible for the subcontract, made a grant toward improving working conditions in India, and partnered with other organizations to help monitor the kind of work done in more informal settings, such as beadwork.

“We strictly prohibit the use of child labor,” said Marka Hansen, Gap North America president. “In 2006, Gap Inc. ceased business with 23 factories due to code violations. We have 90 people located around the world whose job is to ensure compliance with our Code of Vendor Conduct.”

In addition to Gap, the company brands include Banana Republic, Old Navy, and Piperlime. Gap Inc. has more than 3,000 retail stores and uses factories in about 50 countries. Gap employs 90 full-time factory inspectors. In 2006 Gap conducted about 4,300 inspections in more than 2,000 garment factories.

Sources: Gap Inc., Update: Combating Child Labor in the Garment Industry, June 12, 2008, www.Gapinc.com; “Gap: Report of kids' sweatshop ‘deeply disturbing’,” October 29, 2007, http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/10/29/gap.labor/index.html; “The Gap Caps Work With Child Labor Vendor,” November, 15, 2007, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/11/15/business/main3505020.shtml?source=RSSattr . . .; “The Gap Falls Into Child Labor Controversy,” October, 29, 2007, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/10/29/business/main3422618.shtml?source+RSSattr. . . .

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Scarcity and Specialization

As we have seen from the very beginning, the study of economics is rooted in scarcity: The resources necessary to produce goods and services are scarce relative to the material wants and needs those goods and services satisfy. One way to lessen the scarcity problem is through increases in production gained by specialization.

Specialization occurs when productive resources concentrate on a narrow range of tasks or on the production of a limited variety of goods and services. The concept applies to all factors of production but is most often associated with individuals and locations. For example, a doctor may specialize in cardiovascular surgery, a student may select economics as her major, and northern California is known for its wine production.

Specialization

Productive resources concentrate on a narrow range of tasks or the production of a limited variety of goods and services.

Specialization permits greater levels of production than would be attained without it. By concentrating on one productive activity, a resource can be used more efficiently—and greater efficiency results in greater output without raising costs. Specialization, however, depends on the ability to sell what one produces and buy what one needs from someone else, or on the ability to trade. Thus, access to appropriate markets where trade can take place is a prerequisite to specialization.

TABLE 16.4 Production Possibilities from 1 Unit of Resources

The United States and Japan have a choice of producing either corn or high-definition television sets when employing 1 unit of resources.

| Country | Production Possibilities |

| United States | 10 tons of corn or 1 HDTV |

| Japan | 1 ton of corn or 10 HDTVs |

Specialization occurs on an international level when countries concentrate their productive efforts on the goods and services they are best at producing and trade for the goods and services that are most costly to produce. A country that has a relatively inexpensive labor force might specialize in producing goods requiring substantial labor inputs, a country with good agricultural resources might concentrate on growing crops or on livestock, and a country possessing technologically advanced equipment and production methods might use these to its benefit. When each country concentrates on what it does more efficiently than other countries, international specialization increases total production and lessens the scarcity problem on a global level.

The Principle of Comparative Advantage

International trade can lessen the scarcity problem if each country produces and trades on the basis of its comparative advantage. Comparative advantage is practiced when a country produces those goods and services for which it has a cost advantage in comparison to other countries and trades for what it is less adept at producing. If countries produce and trade on the basis of their comparative advantages, the world will have more goods and services than it otherwise would. In essence, the principle of comparative advantage is a restatement of the benefits of international specialization.

Comparative Advantage

One country has a lower opportunity cost when producing a good or service than does another country.

A country has a comparative advantage in the production of a good or service when the opportunity cost of producing that item is less in that country than in another country. Fewer goods or services are given up to produce a unit of a particular item in the country with the comparative advantage than in another country.

To illustrate how comparative advantage works, and how it results in overall gains in output, let us examine a simple hypothetical production and trade relationship between the United States and Japan.

Assume that with 1 unit of resources (where 1 unit is equal to a defined combination of land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship), the United States can produce either 10 tons of corn or 1 high-definition television set. Assume further that with 1 unit of resources Japan can produce either 1 ton of corn or 10 high-definition television sets. Table 16.4 illustrates these production possibilities.

The comparative advantage of each country in this example is obvious: The United States has the advantage in corn, and Japan in television sets. This can be verified by comparing the opportunity costs in each country.

TABLE 16.5 Production from 2 Units of Resources per Country without Specialization

When the United States and Japan both produce corn and high-definition television sets with 2 units of resources each, 11 tons of corn and 11 television sets can be produced.

| Item | Amount of Production |

| Corn | 10 tons (U.S.) + 1 ton (Japan) = 11 tons total production |

| Television sets | 1 HDTV (U.S.) + 10 HDTVs (Japan) = 11 HDTVs total production |

The opportunity cost (measured in forgone television sets) of producing 10 tons of corn in the United States is just 1 television set, while the opportunity cost of producing 10 tons of corn in Japan is 100 television sets. This gives the United States the comparative advantage in corn because its opportunity cost of producing corn is lower. The opportunity cost of producing 1 television set in the United States is 10 tons of corn, whereas in Japan producing 1 television set would mean giving up only one-tenth of a ton of corn. The opportunity cost of producing a television set is lower in Japan, giving Japan the comparative advantage in television sets.

Gains from Specialization and Trade Let us continue the corn and television example to illustrate why the world would be better off in terms of the amounts of goods and services produced if comparative advantage and trade were exercised. Assume now that the United States has 2 units of resources to employ and uses 1 unit for the production of corn and 1 unit for the production of television sets. In this case, the United States will produce 10 tons of corn and 1 television set. Assume further that Japan also has 2 units of resources to employ and also uses 1 unit for the production of corn and 1 unit for television sets. In this case Japan will produce 1 ton of corn and 10 television sets. With resources employed in this way, total production of these items by these two countries is 11 tons of corn and 11 television sets. This is shown in Table 16.5.

Now assume that Japan and the United States each decides to devote its productive resources to the good in which it has the comparative advantage and to engage in international trade. The United States will now devote its 2 units of resources to corn production, resulting in 20 tons of corn instead of 10 tons of corn and 1 television set. With Japan's 2 units of resources, it will now produce 20 television sets instead of 10 television sets and 1 ton of corn. Table 16.6 summarizes the resulting production when each country specializes its production based on its comparative advantage.

The increased total production registered in Table 16.6 (as compared to the numbers in Table 16.5) demonstrates the benefits of specialization and trade. Without international specialization, a total of 11 tons of corn and 11 television sets can be produced by both countries together. With production based on comparative advantage, Japan and the United States can together produce a total of 20 tons of corn and 20 television sets using the same amount of resources. Clearly, the scarcity problem can be lessened through the exercise of comparative advantage and trade.

TABLE 16.6 Production from 2 Units of Resources per Country with Specialization

When countries devote their resources to producing goods in which they have a comparative advantage, the total production of these goods increases.

| Item | Amount of Production |

| Corn | 20 tons (U.S.) + 0 ton (Japan) = 20 tons total production |

| Television sets | 0 HDTVs (U.S.) + 20 HDTVs (Japan) = 20 HDTVs total production |

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

- Assume that Canada can produce 8 tons of wheat or 4 tons of soybeans with 1 unit of resources and that Brazil can produce 4 tons of wheat or 8 tons of soybeans with 1 unit of resources.

- The opportunity cost to Canada of producing 1 ton of wheat is_________tons of soybeans, and the opportunity cost to Brazil of producing 1 ton of wheat is_________tons of soybeans. The country with the comparative advantage in wheat is_________.

- The opportunity cost to Canada of producing 1 ton of soybeans is_________tons of wheat, and the opportunity cost to Brazil of producing 1 ton of soybeans is_________tons of wheat. The country with the comparative advantage in soybeans is_________.

- If Canada and Brazil each has 2 units of resources, and each uses 1 unit for the production of wheat and the other for the production of soybeans, together they will produce_________tons of wheat and_________tons of soybeans.

- If each country uses its 2 units of resources to produce the crop in which it has the comparative advantage, Canada will produce_________tons of_________and Brazil will produce_________tons of_________.

- If, for political or other reasons, each country uses its 2 units of resources to produce the crop in which it does not have the comparative advantage, together they will produce_________tons of wheat and_________tons of soybeans.

- Assume that Mexico can produce 500 lamps or 100 gallons of gasoline with 1 unit of resources and that Venezuela can produce 25 lamps or 100 gallons of gasoline with 1 unit of resources.

- The opportunity cost to Mexico of producing 1 lamp is_________gallons of gasoline, and the opportunity cost to Venezuela of producing 1 lamp is_________gallons of gasoline. The country with the comparative advantage in lamps is_________.

- The opportunity cost to Mexico of producing 1 gallon of gasoline is_________lamps, and the opportunity cost to Venezuela of producing 1 gallon of gasoline is_________lamps. The country with the comparative advantage in gasoline is_________.

- If Mexico and Venezuela each has 2 units of resources, and each uses 1 unit for the production of lamps and the other for the production of gasoline, together they will produce_________lamps and_________gallons of gasoline.

- If each country uses its 2 units of resources to produce the good in which it has the comparative advantage, Mexico will produce_________(of)_________and Venezuela will produce_________(of)_________.

- If, for political or other reasons, each country uses its 2 units of resources to produce the good in which it does not have the comparative advantage, together they will produce_________lamps and_________gallons of gasoline.

Answers can be found at the back of the book.

Does the principle of comparative advantage work in the real world? How closely is it followed? In order to fully exercise comparative advantage and reap its benefits, an environment of free trade is necessary. Free trade occurs when goods and services can be bought and sold by anyone in any country with no restrictions. Everyone is free to choose with whom he or she deals, regardless of location, and there are no barriers to trade. Import taxes are not imposed to artificially raise prices and discourage purchases of foreign-made goods, and limits are not set on the amounts that can be bought and sold. This free flow of trade permits specialization to work to its fullest. You can check your grasp of the material in this section by answering the questions in Test Your Understanding, “Comparative Advantage.”

Free Trade

Goods and services can be exported and imported by anyone in any country with no restrictions.

FREE TRADE AND PROTECTIONISM

In practice, countries often impose restrictions that impede the international flow of goods and services. Such policies, despite the fact that they may reduce a country's ability to fully exploit its various comparative advantages, are generally justified on the grounds that they are in the best interest of the nation that is imposing them.

The philosophy that it is in a country's best interest to restrict free trade is known as protectionism. According to the protectionist viewpoint, unrestricted importing and/or exporting may lead to economic and noneconomic consequences injurious to the economy as a whole, to certain groups within the economy such as workers in particular industries, and/or to national security. Because of these potentially adverse effects, protectionists argue for restrictions on international trade.

Protectionism

The philosophy that it is in the best interest of a country to restrict free trade.

Protectionist policies can be employed in varying degrees: A nation may choose to have detailed regulations or loose restrictions. Also, a nation may alter the degree to which it relies on protectionist policies as economic and noneconomic conditions change.

The merits of free trade and protectionism have been debated for hundreds of years. (See the Critical Thinking Case at the end of this chapter, “A Petition by Frederic Bastiat, 1801–1850,” which excerpts a satirical protectionist plea from the early 1800s.) In light of this debate, it is useful to know some arguments on both sides of the issue in order to better form your own opinions. But before introducing the cases for free trade and for protectionism, we will examine the different types of trade-restricting policies that a country may employ.

Trade-Restricting Policies

Three basic policies have traditionally been used to restrict trade: tariffs, quotas, and embargoes. In addition to these, some countries have developed more subtle measures to discourage trade, such as setting very high product standards or an overwhelming number of bureaucratic steps to import a product.

A tariff is a tax placed on an import. Tariffs have the effect of raising import prices to domestic buyers, thereby making foreign goods less attractive. This reduces the quantities of imports demanded and makes it easier for domestic producers to sell their own products.

Tariff

A tax on an import.

Examples of tariffs on goods entering the United States are given in Table 16.7. The columns to the right classify nations into three categories for tariff purposes. The column headed General is for nations whose products are not imported under any preferential tariff treatment. Countries such as England, France, and Japan fall into this category. The column headed Special is for nations whose products are imported at reduced tariff rates under special programs, and the rates differ with each program. For example, products from Mexico are imported under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Other examples of special programs are the Automotive Products Trade Act and the Generalized System of Preferences, which allows developing nations such as Belize and Nepal to sell to the United States at reduced tariff rates or tariff-free. Finally, the column headed Designated Countries is for a short list of nations such as Cuba, Laos, and North Korea.5

Table 16.7 illustrates that tariffs can be expressed in dollar terms or as a percentage of the value of the imported product, and that they differ according to the three country categories. Designated countries pay the highest tariffs, while countries that receive special treatment pay the lowest or, in some cases, no tariff at all.

TABLE 16.7 Tariffs for Selected Goods

Tariffs, which raise the prices of imported goods to domestic buyers, can be expressed in dollar terms or as a percentage of the value of the imported good.

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission, Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States, 2012, Revision 2 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), pp. 3-23, 4-43, 8-6, 62-16, 62-42, 63-14, 64-3, 92-3, 93-3.

Quotas are restrictions on the quantities of various goods that can be imported into a country. For example, a country may impose a quota allowing only 10 million bushels of wheat to be imported from another country over a 1-year period. Once that amount is reached, no more wheat can flow in from the other country for the remainder of the year. A quota, like a tariff, restricts the ability of foreign goods to compete with domestic goods.

Quota

A restriction on the quantity of an item that can be imported into a country.

An embargo is an outright ban on trade in a particular commodity or with a particular nation. For example, the United States and other United Nations member countries imposed embargoes on exports to Iraq in 1990 and to Haiti in 1993 and 1994. These embargoes were imposed for noneconomic reasons: to sanction Iraq in an effort to prompt its withdrawal from Kuwait and to sanction a military government in Haiti in order to restore that country's exiled president. Trade sanctions have also been imposed on Iran, North Korea, Cuba, and Syria.6

Embargo

A ban on trade in a particular commodity or with a particular country.

Free Trade Arguments

Arguments favoring unrestricted international trade center on the ability of free trade to increase economic efficiency, provide a source of competition, and increase the availability of goods while lowering their prices.

Trade, Specialization, and Efficiency Free trade permits the markets in which goods and services are bought and sold to expand, and the possibility of additional sales from expanded markets makes it feasible for resources to specialize in narrower ranges of tasks. In turn, this specialization allows resources to be used more efficiently than would otherwise be the case.

By using resources more efficiently, more goods and services can be produced, lessening the scarcity problem. This was illustrated earlier in the corn and television set example used to explain the principle of comparative advantage.

Increased Competition, Availability of Goods, and Lower Prices Another argument in favor of free trade is that it increases competition in markets. Competition leads to benefits for consumers: There are larger quantities of goods from which to choose, and prices tend to be lower.

Recall the material in Chapter 3 that deals with supply and demand. An increase in supply will lower prices in a competitive market. And, in Chapter 13 we learned that as the number of sellers increases in a market, the ability of an individual firm to exercise control over price and output decreases, and price moves more toward cost. Thus, with foreign competitors in a market, domestic sellers are in less of a position to extract excessive profits.

With free trade, the absence of tariffs benefits the consumer by making foreign goods available at lower prices. In addition, removing quotas has the obvious effect of increasing the amounts of goods available for sale.

In the arguments for free trade, the major beneficiary is the consumer. This is not the case with the arguments for protectionism.

Protectionist Arguments

The main thrust of the protectionist arguments is that, for either economic or noneconomic reasons, it is in the best interest of a nation to place restrictions on imports. The major protectionist arguments center on protection of industries and employment, diversification, and national security.

Protection of Infant Industries and Domestic Employment and Output An infant industry is one in the early stage of its development. Technology, new resources, or innovations, for example, can spawn an industry new to an economy. In the early stages of a new industry, strong competitive pressures from established foreign producers might destroy a prospect for growth. Protectionists argue that it is appropriate to impose trade restrictions to allow the newly forming domestic industry to establish itself.

Infant Industry

An industry in the early stage of its development.

Protectionists also argue that it is appropriate to protect a domestic industry when the availability of foreign goods would lead to lower domestic output and higher domestic unemployment. In this case, the protectionist point of view is to impose trade restrictions that would make it difficult, or impossible, for foreign goods to compete. Support for this argument frequently comes from both manufacturers and labor organizations in specific industries facing strong foreign competition.

Diversification The protectionist argument for diversification is based on the potential risks from developing a dependency on foreign-produced goods rather than home-produced goods because changes in the prices or availabilities of those foreign goods could lead to serious economic disruptions at home. A striking example of this problem is the continuing concern over the U.S. dependency on foreign oil. Huge price increases from time to time have caused some issues in the economy.

Protectionists argue that a country should not specialize to the point where it develops critical dependencies on foreign products. Instead, domestic production should be diversified so that there are feasible alternatives to foreign-produced goods.

National Security For a variety of reasons, arguments have been put forward to impose tariffs, quotas, and embargoes in the name of national security. These reasons include the need to develop strong domestic defense-related industries and the need to diversify in anticipation of interruptions of foreign supplies resulting from military or economic aggression or some other type of international hostility.

It is up to you to decide which of these free-trade and protectionist arguments has greater merit than the others. Application 16.2, “Gloria Flunks the Professor,” is a classic writing concerning the free-trade and protectionism debate. How many of the arguments that were just introduced can you find? How does the application illustrate that a person's position on this issue can be colored by both philosophical commitment and personal interest?

The Real World of International Trade

Most countries do not choose a strict free trade or protectionist philosophy and then adhere only to policies aligned with that philosophy. Instead, these two philosophies are the extremes toward which a country may lean. A country may adopt a comprehensive trade policy based on the principles of free trade or protectionism, or it may adopt more liberal terms of trade with some of its favored trading partners and restrict trade with other countries. Recall from Table 16.7 that the United States gives preferential tariff treatment to goods imported from Mexico and other countries with special trade agreements and imposes higher-than-average tariffs on goods coming in from Laos.

A country's policies concerning international trade tend to shift with changing political and economic conditions. During a recession or economic downswing, a country's mood tends to become protectionist, resulting in a greater tendency to raise tariff barriers than is the case during a period of economic growth. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which was passed in 1930 at the beginning of the Great Depression, raised U.S. tariff rates to some of their highest levels.

Instead of restricting trade, a country will sometimes adopt policies, such as trade subsidies, to promote the export of a domestically produced good. For example, if the United States decided that it wanted to encourage foreign purchases of its domestically produced pianos, it could offer domestic piano manufacturers a subsidy, or payment, for each piano sold abroad—which would allow the manufacturers to lower their prices on the pianos and still make a profit. This policy, which might be considered unfair by foreign piano makers, would be useful if the United States wanted to increase its share of the world piano market.

Trade Subsidy

A government payment to the domestic producer of an exported good.

On occasion a country has been accused of dumping its products in foreign markets. This occurs when a good is sold in a foreign market below its actual cost or below the price at which it is sold in its own domestic market. Countries pursue this policy to eliminate excess production or to gain a greater share of a foreign market.

Dumping

Selling a product in a foreign market below cost or below its price in its own domestic market.

In the interdependent world of foreign trade, a change in a country's trade philosophy, tariffs, quotas, embargoes, subsidies, or dumping may cause retaliation by a trading partner. And there is always the danger that changing policies and retaliations will result in a trade war. When a trade war breaks out, the benefits of specialization on an international basis are jeopardized. No one seems to benefit.

APPLICATION 16.2

GLORIA FLUNKS THE PROFESSOR

GLORIA FLUNKS THE PROFESSOR

It's not easy to be an economist these days. It used to be enough to have a theory with a good, positive name: like Free Trade. Now people actually expect you to understand the real world. . . .

Take last night. I'm having a quiet drink with Professor Dyzmil. He teaches economics at our local university. In sails Larry [who] announces that he just bought a new Honda—top of the line, all the extras. People around the bar mutter, “Wow,” “Great,” and so forth. Gloria [the bartender] just keeps pouring drinks.

Finally she says: “I think it's a shame to buy a foreign car when there's so much unemployment in our own auto industry.”

“Hey,” says Larry, “What am I supposed to buy? . . . Anyway, one car isn't going to make all that much difference to Detroit.”

“I know” Gloria sighs, “but it seems like somebody ought to be doing something to protect our people from all these imports.”

“Protect our people? Your people maybe,” says Larry. “I think it's awfully nationalistic to worry about protecting American autoworkers. My lifestyle is international. Whoever makes the most interesting, least expensive products gets my business.” . . .

[“Besides,] protectionism is bad for the economy. Isn't that right, professor?”

“Absolutely,” says Dyzmil, solemnly. “Quotas and tariffs and other devices to keep out foreign goods raise domestic prices. As a result, the consumer pays more.”

“So what?” says Gloria. “Wouldn't it be worth it if it saved jobs here? . . . ”

Seems like a good point, but the professor isn't impressed. “Very superficial analysis,” he says sternly. “The real problem is that protecting U.S. industries will make them less competitive. Having to compete with foreign goods keeps you on your toes, makes you more conscious of quality and price, more responsive to the needs of the customer. Protectionism makes an industry lazy and inefficient.” . . .

“By that logic,” muses Gloria, “the answer to Japanese imports is to open up our markets to even more imports so our industries will be more efficient. That doesn't make sense.”

“It's true that the U.S. is already pretty much of an open market,” says the professor. “What we need to do is to get other countries to open their economies to free trade.”

“Like?”

“Like Japan,” the professor replies. “Japan is notoriously protectionist. They have an intricate system of rules and regulations and quotas that keep foreign goods out.”. . .

“But if free trade makes a country more competitive and protectionism makes a country less competitive . . . ”

“Yes,” he nods encouragingly.

“And the Japanese markets are protected and ours are open. . . . Then how come the Japanese are so competitive and we're so uncompetitive?”

“Well . . . uh . . .,” stammers Dyzmil, “it's very complicated. For one thing, there are cultural differences. . . . [T]he Japanese work together better. They work more as a unit, as a community. . . .”

“Doesn't sound bad,” says Gloria. “Maybe we ought to try some of that here.”

“No, my dear,” Dyzmil says, shaking his head. “Americans don't like to do things collectively. We thrive on the excitement of competition between individuals.”

“Real exciting to be out of work,” says Gloria, dryly. “A lot of people aren't exactly thriving.”

“Not to worry,” the professor says. “Our old industries are adjusting. And free trade is helping. . . . Old jobs have to die, Gloria. Just like old people. It's a law of economic nature. Jobs will open up in new industries.”

“But aren't imports also taking over the new industries? VCRs are the hottest new item around. I read somewhere that the Japanese made 27 million last year and we made zero.”

“Not to worry,” Dyzmil assures her. “Even if they do take our manufacturing, Americans excel at services.”

“Like laundry?”

“No. Like banking, advertising, computer software.”

“But it stands to reason that Japanese businesses will use Japanese banks and advertising agencies. So as they expand their industry, they'll expand their services too. If they make the computers, won't they eventually make the software?”. . . “Anyway,” she continues, “how many laid off autoworkers are going to get a job in a bank or advertising?”. . .

I can see that the professor is getting annoyed at having to defend free trade. . . . After all, in the hierarchy of economic principles, free trade ranks above the law of gravity.

“Look, Gloria,” says the exasperated scholar, “there are plenty of other places Americans can work. In bars and restaurants, for example. Granted, the jobs pay less.”. . .

“Ok,” says Gloria suddenly, “You've convinced me, but I don't think you've gone far enough with your free trade idea.”

“How's that?”

“Why not extend free trade to economics professors? Maybe the reason that the Japanese economy is better is because Japanese economists are better. So if we got rid of tenure in our universities, we might import some Japanese economists who could show us how to create more jobs by working together.”

“My dear Gloria,” says the stunned professor, . . . “if America exported its economists, who would be left to defend free trade?”

Source: Jeff Faux, “Gloria Flunks the Professor,” Mother Jones (October, 1985), pp. 50–51, © 1985, Foundation for National Progress.

Trade Agreements among Nations Since World War II, world trade has been carried out in a relatively liberal environment thanks to greater international cooperation to reduce tariffs and the work of organizations that facilitate the trading process. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides loans and other financial assistance to nations seeking to improve their competitiveness in world trade. Tariff reductions have occurred in large part as a result of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), under which countries held their first round of talks in 1947. Since then, there have been several rounds of negotiations, each leading to lower tariff rates.

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

An international organization that provides loans and other financial assistance to countries.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

An international forum for negotiating tariffs.

Three landmark trade agreements were negotiated in the early 1990s. In 1992, 12 Western European nations formally joined together as the European Community, or EC. This alliance now includes 27 members with others seeking admission and is called the European Union, or EU, which was introduced earlier in the chapter. The goal of the EU is to create a trading area within which no national barriers slow the movement of people, capital, or goods and services. The EU represents a major world trading power: While less than one-half the size of the United States, in 2012 the combined population of its member countries was sixty percent larger than the population of the United States.7

European Union (EU)

The single unified market formed by the majority of Western European nations; a major trading power.

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, was put in place. This trade agreement among the United States, Canada, and Mexico removed many barriers to trade and investment in these three countries. One of the effects of NAFTA has been the establishment of businesses in Mexico along the border with the United States that tend to import inputs from the United States, process them with cheaper labor, and return the finished products to the United States as exports. While there is evidence that the Mexican economy has benefited from this trade agreement, NAFTA continues to be a source of debate over many issues such as labor conditions and rights, the environment, and unions in the United States.8

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

The treaty creating a unified market involving the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

The third important agreement was the approval in 1993 of the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations. This treaty reduced tariffs and other trade barriers, involved more than 100 nations, and took years to complete. The trade rules agreed to at the Uruguay Round are implemented by the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was founded in 1995 to take over the responsibilities of GATT.

World Trade Organization (WTO)

An organization founded in 1995 to take over the responsibilities of GATT.

The WTO is a forum for countries to sort out trade issues and negotiate trade rules. These trade rules, or WTO agreements, provide some legal ground rules for international commerce. The WTO also works to settle trade disputes. In 2012, there were more than 150 members of the WTO. In addition to trade in goods, the WTO covers trade in services, inventions, and designs.9

In 2004, another regional trade agreement, the Dominican Republic–Central America–United States Free Trade Agreement, or CAFTA-DR, was signed. The seven CAFTA partners—Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, United States—have worked to eliminate trade barriers and expand trade opportunities among themselves. U.S. bilateral trade with these countries increased significantly from 2005 to 2010, and trade among the regional countries increased by 50 percent.10

UP FOR DEBATE

SHOULD TRADE BE RESTRICTED IF IT RESULTS IN ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE?

SHOULD TRADE BE RESTRICTED IF IT RESULTS IN ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE?

Issue During the past few decades, we have become quite aware of the impact on the global environment from the production and consumption of goods and services by people throughout the world. We know that overharvesting trees, emitting carbon in the air and toxins in streams, and even pursuing some fishing practices can destroy air and water quality, tilt our delicate ecological balance, and ruin habitats and species. Global warming, a serious environmental concern, is a relatively new phrase in our vocabulary.

It is apparent that some environmental destruction occurs because of international trade: The ability to participate in a large global market can spur on production habits that are unfriendly to the environment. The capacity to sell cheap wood, clothing, and food all over the globe, rather than solely in home markets, contributes to these destructive practices. So, the question to ponder is: Should trade in a particular product be restricted if its production causes environmental damage?

Yes We are more aware than ever that responsibility for the environment is a global concern that requires global action. Air and water quality destruction isn't isolated to single country: The practices of one country can affect another half a globe away. It is appropriate and necessary that sustainability of the planet be a key component of international trading relationships.

International trade agreements can be vehicles for creating environmental standards of production. They are powerful tools to mandate countries to adopt environmentally safe production practices. If countries like China had to cut toxic air emissions or had to find production methods that ensure safe water quality to be able to trade globally, you can be sure that this would get done.

Furthermore, economic development can be an additional positive impact from agreements that force countries to adopt “green” practices. New technology, industries, and jobs can and do come with new environmental practices.

NO Restricting trade because of environmental issues would be just another excuse to move toward protectionism. Restricting trade hurts consumers because of less competition, fewer products, and higher prices. Just think about the higher prices on clothing in the United States that would result if some of the global factories that produce it were closed.

There are already about 200 international agreements dealing with environmental issues—called multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs)—now in place.a These are more effective and expedient for nations to deal with each other than to create a wholesale ban on a product.

Trade agreements can be difficult to create and enforce. The environment is just another feature to add to the difficulty. And, countries differ in their standards. The United States, for example, might want to set standards so high that it hurts employment and production in another country. Can countries really dictate environmental standards for other countries?

a World Trade Organization, “Understanding the WTO—The environment: a new high profile,” http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/bey2_e.htm.

Gaining consensus on a unified trading program like the EU, NAFTA, or WTO is not easy. Controversy is to be expected when a new treaty changes the economic relations among countries and the economic security of individuals and groups within those countries. In addition, as the world becomes more aware of threats to the environment from the production and consumption of goods and services, there is an added dimension to trade relationships: the issue of whether environmental protection should become part of future trade negotiations. Up for Debate, “Should Trade Be Restricted if It Results in Environmental Damage?”, briefly tackles this thorny and complicated issue. What is your position in this debate?

Summary

- International economics deals with the economic relationships among countries. International trade is concerned with the exporting and importing of goods and services and is important because it affects production, employment, and prices in the trading countries.

- In the United States, international trade has grown over the years. The largest classes of U.S. exports and imports are capital goods, and industrial supplies and materials. Most U.S. trade is with developed countries in Asia, Europe, and North America, particularly China, Japan, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union.

- Specialization occurs when resources concentrate on a narrow range of tasks or on the production of a limited variety of goods and services. It permits greater efficiency and larger levels of output than would otherwise be the case.

- Specialization on an international scale is based on the principle of comparative advantage. A country has a comparative advantage when the opportunity cost of producing a good or service is less in that country than in another. Specialization based on comparative advantage and international trade can increase overall production levels and lessen the scarcity problem. An environment of free trade is necessary for comparative advantage to be fully exercised.

- Free trade occurs when there are no restrictions on the flow of international trade. The alternative to free trade is protectionism, which is based on the argument that restricted trade is in the best interest of a country. Protectionist policies include tariffs, which are taxes on imports; quotas, which are quantity limits on imports; and embargoes, which are outright bans on trading a product or on trade in general.

- The arguments for free trade center on the production gains and efficiencies to be obtained from comparative advantage, the increased availability of goods and services for consumers, and the lower prices and other benefits resulting from more competition in markets.

- The protectionist arguments for trade restrictions include the need to protect infant industries and domestic output and employment, to diversify in case of economic disruptions, and to protect national security. The United States has reverted to protectionist policies at different times in its history.

- In addition to trade-restricting policies, a nation can seek to increase its foreign sales through the use of subsidies and dumping. International agreements, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the agreements creating the European Union, and the North American Free Trade Agreement, have a significant effect on world trade.

Key Terms and Concepts

International trade

Export

Import

U.S. trading partners

Specialization

Comparative advantage

Free trade

Protectionism

Tariff

Quota

Embargo

Free trade arguments

Protectionist arguments

Infant industry

Trade subsidy

Dumping

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

European Union (EU)

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

World Trade Organization (WTO)

Review Questions

- Explain how international trade can affect a country's levels of production, employment, and prices.

- What have been the main export and import categories for the United States in recent years, and who are the primary trading partners of the United States?

- “Comparative advantage is the application of specialization on an international level.” What is meant by this statement? Define comparative advantage and explain how it lessens the basic scarcity problem.

- With 1 unit of resources, China could produce either 2 tons of wheat or 4 tons of rice, and Hungary could produce either 4 tons of wheat or 4 tons of rice. What is China's opportunity cost of 1 ton of wheat and of 1 ton of rice? What is Hungary's opportunity cost of 1 ton of wheat and of 1 ton of rice? Which country has the comparative advantage in wheat? Which country has the advantage in rice?

- Given the information in Question 4, how much wheat and rice would be produced if each country had 2 units of resources and devoted 1 unit to the production of wheat and 1 unit to the production of rice? If each country used both units to produce the item in which it has a comparative advantage, how much wheat and rice would be produced?

- Differentiate among a tariff, a quota, an embargo, a subsidy, and dumping. Explain how each affects trade.

- Summarize the arguments for free trade and for protectionism.

- What are the International Monetary Fund (IMF), General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), European Union (EU), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and World Trade Organization (WTO)? What are the EU and NAFTA countries trying to accomplish?

Discussion Questions

- Over the past few decades, both exports and imports have grown as a percentage of GDP in the United States.

- What effect would an increase in exports have on the level of unemployment and the level of prices in the United States if the economy were operating far below full employment?

- What effect would an increase in imports have on the level of unemployment and the level of prices in the United States if the economy were operating at full employment?

- What effect would dumping a U.S.-produced good in a foreign country have on employment in the United States if that country responded by dumping one of its goods in U.S. markets?

- International trade must occur in free markets if countries' comparative advantages are to be fully exploited. Why is this so? If the United States produced according to its comparative advantage, in what goods and services do you think it would specialize?

- The level of tariffs on foreign-produced cars is a source of continual debate in the United States. What is the current tariff status of automobiles imported from Japan, Germany, and South Korea? Would you favor increasing or decreasing these tariffs? Why?

- Some people favor free trade while others favor protectionism. This suggests that some groups gain from free trade while others gain from protectionism. Who gains and who loses from free trade and from protectionism? What is your position on free trade and protectionism, and why do you hold this point of view?

- Protectionists argue that putting a tariff on a good protects a domestic industry's output and employment. Others argue that a country hurt by the tariff may retaliate by restricting trade from the country imposing the tariff. The result could be a loss of output and employment in an exporting industry of the country that initiated the tariff action. Comment.

- There were strong opinions supporting and opposing the passage of NAFTA. What groups would you expect to favor an agreement such as this, and what groups would you expect to oppose it?

- The EU, NAFTA, and CAFTA have eased trade among European countries; among the United States, Mexico, and Canada; and among the United States and Central American countries, respectively. Do you see these developments easing trade worldwide or leading to the growth of “trade blocs” that are virtually impossible for traders from other countries to enter?

Critical Thinking Case 16

A PETITION (BY FREDERIC BASTIAT, 1801–1850)

Critical Thinking Skills

Using satire to make a point

Identifying flaws in arguments

Evaluating the impacts of decisions on different groups

Economic Concepts

Free trade

Protectionism

Protectionist arguments

From the Manufacturers of Candles, Tapers, Lanterns, Candlesticks, Street Lamps, Snuffers, and Extinguishers, and from the Producers of Tallow, Oil, Resin, Alcohol, and Generally of Everything Connected with Lighting.

To the Honorable Members of the Chamber of Deputies.

Gentlemen: . . .

We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price; for the moment he appears, our sales cease, all the consumers turn to him, and a branch of French industry whose ramifications are innumerable is all at once reduced to complete stagnation. This rival, which is none other than the sun, is waging war on us . . . mercilessly . . . .

We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains . . . and blinds—in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures through which the light of the sun is wont to enter houses . . . .

Be good enough, honorable deputies, to take our request seriously, and do not reject it without at least hearing the reasons that we have to advance in its support.

First, if you shut off as much as possible all access to natural light, and thereby create a need for artificial light, what industry in France will not ultimately be encouraged?

If France consumes more tallow, there will have to be more cattle and sheep, and consequently, we shall see an increase in cleared fields, meat, wool, [and] leather . . . .

If France consumes more oil, we shall see an expansion in the cultivation of the poppy, the olive, and rapeseed . . . .

Our moors will be covered with resinous trees . . . . Thus, there is not one branch of agriculture that would not undergo a great expansion . . . .

It needs but a little reflection, gentlemen, to be convinced that there is perhaps not one Frenchman, from the wealthy stockholder . . . to the humblest vendor of matches, whose condition would not be improved by the success of our petition.

We anticipate your objections, gentlemen, but there is not a single one of them that you have not picked up from the musty old books of the advocates of free trade . . . .

Will you tell us that, though we may gain by this protection, France will not gain at all, because the consumer will bear the expense?

We have our answer ready:

You no longer have the right to invoke the interests of the consumer. You have sacrificed him whenever you have found his interests opposed to those of the producer. You have done so in order to encourage industry and to increase employment. For the same reason you ought to do so this time too . . . .

Questions

- What protectionist arguments are presented by the petitioners?

- Why is this petition absurd? From this, should you conclude that all protectionist arguments are absurd?

- Based on this petition and what you read earlier in the chapter, how confident are you in a country's ability to develop a trade policy that simultaneously benefits domestic producers and consumers?

- Can you create a satire that does to free trade what this does to protectionism?

Source: Frederic Bastiat, “A Petition,” Arthur Goddard, trans. and ed., Economic Sophisms (Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1964), pp. 57–60.

1 U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, News, January 12, 2006, p. 10.

3 U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, 131st ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2011), p. 812.

4 The 27 member countries of the EU in 2012 are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In 1992, 12 of these countries formed the European Community, or EC. The name was later changed to the European Union. See http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/eu/c12191.htm.

5 U.S. International Trade Commission, Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2005) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), General Notes, pp. GN 3, 6.

6 U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, “OFAC Country Sanctions Programs,” http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/OFAC/programs/.

7 U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, www.cia.gov/cia/publications/the-world-factbook.

8 Jeff Fugate, “A Recipe for Success,” Yale Economic Review, http://www.yaleeconomicreview.com/spring2005/nafta.php.

9 World Trade Organization, www.wto.org.

10 Office of the United States Trade Representative, “CAFTA—DR (Dominican Republic—Central America FTA),” www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/cafta-dr-dominican-republic-central-america-fta.