CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To introduce the main forms of government intervention into the operation of markets, and some reasons for this intervention.

To identify the major federal antitrust statutes and the anticompetitive practices they address.

To examine different types of mergers and their possible anticompetitive effects.

To identify the forms and organization of government regulation.

To distinguish between industry regulation and social regulation, and to offer justifications for each.

To introduce issues about the effectiveness of regulation, and policy concerns growing out of the increasing internationalization of economic activity.

In the last chapter, we saw that a seller's price, output, promotional strategy, profit, and efficiency are all influenced by the type of market it is in and degree of competition it faces. Obviously, markets and competition play an important role in economic decision making and in determining the well-being of businesses and households.

Economies where decisions are made primarily by individual businesses and households are built on the philosophy that free markets and competition should be at the foundation of economic activity. Although the U.S. economy is based on this philosophy, historically government has intervened in the operation of markets in several important ways. (Recall in Chapter 2 the discussion of market failure and government intervention.) In this chapter we will pick up the discussion of government intervention and focus on the two essential ways government influences competition and market forces in the United States: antitrust enforcement and regulation.

We typically find a wide range of views on the appropriateness of government intervention. Some people feel that current intervention is too extensive; others feel that it is inadequate. Some people hold that government intervention is not achieving its intended results or that it creates an unjustified administrative or financial burden on businesses; others are satisfied with its effects and comfortable with the requirements it imposes.

Why would people who basically favor free markets seek government intervention in the operation of those markets? Government intervention might be sought where the number of firms in a market is so small that strong competition is unlikely to occur or where one firm is so large that it significantly weakens competitive forces. Government intervention might also be sought in the public interest: The public might be better served by a single large, efficient seller that answers to a public authority than by several less efficient, smaller sellers competing with one another. This is often the case with the distribution of gas, electric, and water services.

Another reason for seeking government intervention is security. As the economist John Maurice Clark wrote:

[C]ompetition has two opposites: which we may call monopoly and security…. Nearly everyone favors competition as against monopoly, and nearly everyone wants it limited in the interest of security. And hardly anyone pays much attention to the question where one leaves off and the other begins.1

Finally, government may be called in to intervene when consumers or workers can be hurt by dangerous products or working conditions. Protection may be sought when people believe that the market does not provide it.

Competition introduces some risks for businesses, and the desire to reduce these risks may inspire support for some government intervention. For example, antitrust laws specifying the ground rules about allowable competitive practices may reduce the risk of failure for smaller or weaker sellers in a market. Laws that regulate monopolies, such as gas or electric suppliers, increase security for consumers by ensuring that these firms continue to supply the market at prices that are regulated.

ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT

Antitrust enforcement centers on a series of laws designed to promote the operation of market forces by limiting certain practices that reduce competition. Specifically, antitrust laws are aimed at two broad categories of practices.

Antitrust Laws

Laws prohibiting certain practices that reduce competition.

The first is monopolization and attempts to monopolize, which occur when a firm, through unreasonable means, acquires or attempts to acquire such a large share of its market that it does not feel strong competitive pressure from its rivals. The effect that a firm with a great deal of market power can have on competition has been compared by the economist Walter Adams to a poker game where one player brings much more money to the table than the others.

Monopolization and Attempts to Monopolize

A firm acquires or attempts to acquire a monopoly share of its market through unreasonable means.

[I]n a poker game with unlimited stakes, the player who commands disproportionately large funds is likely to emerge victorious. If I have $100 while my opponents have no more than $5 each, I am likely to win regardless of my ability, my virtue, or my luck.2

The second category of practices at which antitrust laws are aimed is combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade. This includes acts carried out jointly by two or more firms that unreasonably limit competition, such as price fixing and the division of sales territories. Monopolization and attempts to monopolize, and combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, are explained more fully as we review the major antitrust statutes.

Combinations and Conspiracies in Restraint of Trade

Practices carried out jointly by two or more firms that unreasonably restrict competition.

Antitrust enforcement is carried out by both the federal and state governments, with the main responsibility falling on the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission at the federal level. In addition to federal and state enforcement, private parties such as businesses can bring charges that other companies and/or individuals have violated the laws.

Administration of the antitrust laws depends heavily on the courts and is carried out on a case-by-case basis, where each violation is treated separately. In some instances a suit may be dropped because it is judged to have insufficient merit to go to trial, or a pretrial settlement may be reached where the accused firm promises to discontinue a practice or arrives at some other agreement with the opposing side. In other instances a trial may be required before the issue is resolved. Antitrust disputes can become long, costly, and complicated.

The Antitrust Laws

At the federal level, there are five main antitrust laws: the Sherman Act (1890), the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914), the Clayton Act (1914), the Robinson-Patman Act (1936), and the Celler-Kefauver Act (1950). The Robinson-Patman and Celler-Kefauver acts both amend the Clayton Act.

Sherman Act

Original and most broadly worded federal antitrust statute; condemns combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, and monopolization and attempts to monopolize.

The Sherman Act (1890) The original and most broadly worded federal antitrust statute is the Sherman Act. When people speak of this act, they tend to refer to it by sections.

- Section 1 condemns combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, and

- Section 2 attacks monopolization and attempts to monopolize.

Combinations and conspiracies condemned by Section 1 of the Sherman Act are either per se or rule of reason violations. Per se violations are agreements between firms where proof of the agreement is sufficient to establish guilt: There is no defense for a per se violation. Price fixing, division of sales territories among competitors, tying arrangements, and exclusive dealing arrangements are included in this category.3

Per Se Violations

Anticompetitive agreements between firms where proof of the agreement is sufficient to establish guilt; includes price fixing and division of sales territories.

Price fixing occurs when sellers take joint action to influence prices. An agreement between competing sellers about the prices they will charge their buyers or the price below which they will not sell would be price fixing, as would an agreement on a system for determining who will submit the lowest offer when pricing is done with sealed bids. With price fixing, competition is diminished and sellers act more like monopolists.

Price Fixing

Joint action by sellers to influence their product prices; considered anticompetitive.

Territorial division occurs when competing firms divide a sales area among themselves. For example, two firms competing in a national market might agree that one takes the territory east, and the other takes the territory west, of the Mississippi River. As with price fixing, territorial division diminishes competition.

Territorial Division

Joint action by sellers to divide sales territories among themselves; considered anticompetitive.

A tying arrangement occurs when a firm will sell its product to another firm only if the other firm agrees to also buy different products from the seller. For example, Firm A will sell its piece of advanced computer hardware to Firm B only as long as Firm B also buys other types of hardware from Firm A. This can hurt competition between Firm A and the other firms that produce and sell the other types of hardware.4

Tying Arrangement

A buyer can obtain a good from a seller only by purchasing another good from the same seller.

An exclusive dealing arrangement occurs when a firm will sell its product to another firm only if the buying firm agrees to not get a comparable product from another supplier. For example, suppose that Firm C makes a widely recognized piece of high quality electronic equipment that goes into large-scale communications systems. Suppose also that there are several other firms that make similar equipment and compete with Firm C. To get an advantage over its competitors, Firm C will sell its equipment to businesses producing these communications systems only if the businesses agree to not purchase similar equipment from any of Firm C's competitors. This can hurt competition between Firm C and its competitors.

Exclusive Dealing Arrangement

A firm will sell its product to another firm if the buying firm gets this product only from the selling firm.

Both tying and exclusive dealing arrangements can be tried under the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act.

Rule of reason violations occur when firms come together in a way that may or may not unreasonably restrain trade. With the rule of reason, there is no blanket condemnation of business practices like there is with price fixing and territorial division. Rather, each challenged practice must be examined to see whether in this particular case the restraint is unreasonable.

Rule of Reason Violations

Actions that may or may not be unreasonable restraints of trade.

Activities of industry trade associations and joint ventures fall under the rule of reason umbrella. A trade association is an organization of firms in a particular industry, such as construction or furniture manufacturing, that performs certain functions to benefit its members. If a trade association collects data on overall industry trends and general information on supply conditions or buyer behavior and reports it to all its members, the trade association may enhance competition by improving the general state of knowledge in the industry. But if the information gives specific details on the terms of each firm's sales and the names of its buyers, or if the information is not equally available to all interested parties, the trade association's information gathering might help to foster a price-fixing agreement or division of buyers among sellers and would therefore be subject to condemnation under Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

Trade Association

An organization representing firms in a particular industry that performs functions to benefit those firms.

A joint venture is a cooperative effort by two or more firms that is limited in scope. The operation of an automobile plant by a U.S. and a Japanese manufacturer or the drilling for oil in a remote part of the world by several firms acting together would be examples of joint ventures. As with trade association activities, the legality of joint ventures must be judged on a case-by-case basis to determine whether competition has been unreasonably restricted. For example, in one case, a joint venture might allow two firms to have the resources needed to succeed in a new market that neither of them alone would have been able to enter and survive, and in another case, a joint venture would give the two firms sufficient resources and power to drive smaller competitors out of the market.

Joint Venture

A cooperative effort by two or more firms that is limited in scope.

Cases involving Sherman Act Section 2 violations of monopolization and attempts to monopolize rest largely on two issues:

- the specific actions taken by a firm that demonstrate its intent to monopolize its market; and

- the firm's share of its market.

Where the firm's market share is small and it is clearly not a monopolist, an attempt to monopolize may be inferred from such actions as pricing below cost to drive rivals out of the market or contracting with critical suppliers or distributors to foreclose their services to the firm's rivals.

For firms with larger market shares, monopolization may be inferred less from what the firm does and more from its relative size in comparison to its rivals. For example, in United States v. Aluminum Company of America, a leading monopolization case, the court enunciated a rough guide for analyzing Sherman Act monopolization questions known as the “30-60-90 rule”: “[A greater than ninety per cent share of the market] is enough to constitute a monopoly; it is doubtful whether sixty or sixty-four per cent would be enough; and certainly thirty-three per cent is not.”5

An extremely important aspect of monopolization cases is the definition of the relevant market, which was discussed in Chapter 13. Ordinarily, the broader a market is defined in terms of its geographic boundaries and/or number of substitute products, the smaller will be the share of that market taken by any one firm. The narrower a market is defined, the larger will be the share taken by the firm. Thus, it may be to the advantage of a firm accused of monopolizing a market to define that market as broadly as possible.

Application 14.1, “Cases Involving the Sherman Act,” gives excerpts from the court records of some important and influential antitrust cases dealing with price fixing, tying arrangements, and exclusive dealing arrangements that were brought under the Sherman Act. The decision of the court in each case is also provided. Can you explain how competition would have been injured in each case?

We might warn you before reading Applications 14.1 and 14.2, both of which deal with court rulings, that you will be getting a first-hand opportunity to see the complexity in the writing of court documents. They are not always easy to read.

The Federal Trade Commission Act (1914) The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was created by the Federal Trade Commission Act and granted power to “prevent persons, partnerships, or corporations, … from using unfair methods of competition in commerce.”6 Included among unfair methods of competition are antitrust violations.

Federal Trade Commission Act

Created the Federal Trade Commission and empowered it to prevent unfair methods of competition, which include antitrust violations.

APPLICATION 14.1

CASES INVOLVING THE SHERMAN ACT

CASES INVOLVING THE SHERMAN ACT

Price Fixing: F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd et al. v. Empagran S. A. et al. (2004) The Foreign Trade Antitrust Improvements Act of 1982 (FTAIA) … provides that the Sherman Act “shall not apply to conduct involving trade or commerce … with foreign nations,” … but creates exceptions for conduct that significantly harms imports, domestic commerce, or American exporters. In this case, vitamin purchasers filed a class action [suit] alleging that vitamin manufacturers and distributors had engaged in a price fixing conspiracy, raising vitamin prices in the United States and foreign countries, in violation of the Sherman Act. As relevant here, defendants moved to dismiss the suit as to the … foreign companies located abroad, who had purchased vitamins only outside United States commerce….

Ruling Where the price-fixing conduct significantly and adversely affects both customers outside and within the United States, but the adverse foreign effect is independent of any adverse domestic effect, the FTAIA exception does not apply, and thus, neither does the Sherman Act, to a claim based solely on the foreign effect.

Vertical Price Fixing: Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., DBA Kay's Kloset … Kay's Shoes (2006) Given its policy of refusing to sell to retailers that discount its goods below suggested prices, [Leegin, Inc.] stopped selling to [PSKS's] store. PSKS filed suit, alleging … that Leegin violated the antitrust laws by entering into vertical agreements with its retailers to set minimum resale prices. The District Court [where the case was first heard] excluded expert testimony about Leegin's pricing policy's precompetitive effects on the grounds that [the landmark 1911 Case] Dr. Miles Medical Co. v. John D. Parks & Sons, Co., 220 U.S. 373, makes it per se illegal under of the Sherman Act for a manufacturer and its distributor to agree on the minimum price the distributor can charge for the manufacturer's goods. At trial, PSKS alleged that Leegin and its retailers had agreed to fix prices, but Leegin argued that its pricing policy was lawful under §1.

Ruling [The Supreme Court held that] Dr. Miles is overruled, and vertical price restraints are to be judged by the rule of reason.

Tying Arrangements: Illinois Tool Works, Inc. et al. v. Independent Ink, Inc. (2005) [Illinois Tool Works and other adjoined companies] … manufacture and market printing systems that include a patented printhead and ink container and unpatented ink, which they sell to original equipment manufacturers who agree that they will purchase ink exclusively from [Illinois Tool and the other companies] and that neither they nor their customers will refill the patented containers with ink of any kind. [Independent Ink, Inc.] developed ink with the same chemical composition as [Illinois Tool and the other companies'] ink. After … Trident's [one of the companies with Illinois Tool, patent] infringement action [against Independent Ink] was dismissed, [Independent Ink] filed suit seeking a judgment of noninfringement and invalidity of Trident's patents on the grounds that [Trident, Illinois Tool Works and the other companies] are engaged in illegal “tying” and monopolization in violation of § 1 and § 2 of the Sherman Act.

Ruling Because a patent does not necessarily confer market power upon the patentee, in all cases involving a tying arrangement, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant has market power in the tying product [in this case the printhead and ink container].

Exclusive Dealing Arrangements: American Needle, Inc. v. National Football League et al. (2010) Respondent National Football League (NFL) is an unincorporated association of 32 separately owned professional football teams, also [defendants] here. The teams, each of which owns its own name, colors, logo, trademarks, and related intellectual property, formed [defendant] National Football League Properties (NFLP) to develop, license, and market that property. At first, NFLP granted nonexclusive licenses to [American Needle] and other vendors to manufacture and sell team-labeled apparel. In December 2000, however, the teams authorized NFLP to grant exclusive licenses. NFLP granted an exclusive license to respondent Reebock International Ltd. to produce and sell trade-marked headware for all 32 teams. When [American Needle's] license was not renewed, it filed this action alleging that the agreements between respondents violated the Sherman Act, §1 of which makes “[e]very contract, combination … or, conspiracy, in restraint of trade” illegal. Respondents answered that they were incapable of conspiring within §1's meaning because the NFL and its teams are, in antitrust law jargon, a single entity with respect to the conduct challenged.

Ruling The alleged conduct related to licensing of intellectual property constitutes concerted action that is not categorically beyond §1's coverage.

Sources: F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd et al. v. Empagran S.A et al. 542 U.S. 155 (2004), p. 155; Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., DBA Kay's Kloset… Kay's Shoes. 551 U.S. 877 (2006), p. 877; Illinois Tool Works, Inc. et al. v. Independent Ink, Inc. 547 U.S. 28 (2005), p. 28; American Needle, Inc. v. National Football League et al. 130 S. Ct. (2010), p. 2201; supremecourt.gov/opinions/09pdf/08-661.pdf.

When the FTC thinks that a business is engaged in unfair competition, it can issue a complaint and arrange a hearing to determine whether the practice should be prohibited. If it is found that the practice is unfair competition, the FTC can issue a “cease and desist order” requiring the firm to stop the activity. If the firm fails to follow the order, or if it thinks the order is incorrect, either the FTC or the firm can have the order brought before a court for a ruling.7

The Clayton Act (1914) Unlike the Sherman Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act, which are not specific as to the practices they condemn, the Clayton Act is directed toward several particular activities that “substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.”8 These include tying and exclusive dealing arrangements, also subject to the Sherman Act, interlocking directorates, price discrimination, and mergers and acquisitions.

Clayton Act

Federal antitrust statute prohibiting specific activities that substantially reduce competition or tend to create a monopoly.

Interlocking directorates occur where the same person sits on the boards of directors of different corporations: for example, the same person is on the boards of a health care group and a banking corporation. Interlocking directorates are not necessarily anticompetitive, but injury to competition could occur if, for example, a person sitting on the boards of two firms competing in the same market enables them to communicate about prices, or a person on the boards of corporations in a buyer–seller relationship gives the seller an unfair advantage over its rivals with regard to major purchases by the buyer.

Interlocking Directorates

The same person sits on the boards of directors of different corporations.

In each of the activities addressed by the Clayton Act, as well as those included under its amendments, the practices themselves do not automatically constitute violations of the antitrust laws. They become violations only when the activities tend to significantly reduce competition or create a monopoly.

The Robinson-Patman Act (1936) Section 2 of the Clayton Act condemns price discrimination when it weakens competition or leads to a monopoly. The Robinson-Patman Act elaborates further on that condemnation. Price discrimination occurs when a seller charges different buyers different prices for the same product. If a firm sells an item at a particular price to one buyer and sells exactly the same item with exactly the same treatment and service to another buyer at a lower price, price discrimination has occurred.

Robinson-Patman Act

Federal antitrust statute concerned with anticompetitive price discrimination; amends Section 2 of the Clayton Act.

Price Discrimination

Different buyers acquire the same product from the same seller with the same treatment and service but pay different prices.

Price discrimination can injure competition between a seller and its rivals. Through price discrimination, a seller can lower its price to buyers where there is intense competition from a rival, while keeping the price unchanged, or even raising it, for customers where it is not facing competition. If the rival is unable to meet these price cuts, it may lose sales and perhaps be driven from the market.

A buyer's market position, particularly at the wholesale level, can be injured when it pays a higher price than its rivals. The difference in price paid by the discriminated-against firm raises its costs, causing it, in turn, to charge a higher price or absorb the higher costs through forgone profit, either of which damages its competitive position.

The Robinson-Patman Act attacks outright price discrimination as well as several types of “indirect” price discrimination, such as granting quantity discounts on terms that only a few large buyers can meet, paying purchasers for services that have not been rendered, and treating buyers unequally in providing sales facilities.9

The Celler-Kefauver Act (1950) Section 7 of the Clayton Act deals with anticompetitive mergers and acquisitions, and is amended by the Celler-Kefauver Act. A business can be acquired or merged with another in two ways: by the purchase of a controlling number of shares of stock or by the outright purchase of assets. The Clayton Act condemned anticompetitive acquisitions through stock purchases but said nothing about the purchase of assets. This loophole was closed by the Celler-Kefauver Act.10

Celler-Kefauver Act

Federal antitrust statute concerned with anticompetitive mergers and acquisitions of firms; amends Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

As we learned in Chapter 10, there are three main types of mergers: horizontal, vertical, and conglomerate. Each type of merger can have potentially anticompetitive effects. A horizontal merger occurs where two sellers competing in the same market join together. When two extremely small sellers in a market merge, the consequence may not be noticeable: A small dairy farmer buying a second farm will have no effect on the dairy market. But where the acquiring and/or acquired firm has a substantial market share, their joining may have an anticompetitive effect by creating a larger organization with an even greater share of the market.

Horizontal Merger

A merger between two sellers competing in the same market.

A vertical merger involves the joining of a firm with a supplier or a distributor; it may be anticompetitive if it forecloses the firm's rivals from key suppliers or distributors. If a major developer/builder were to acquire both of the existing lumber yards in an area, the local supply of building materials could be foreclosed to rival developers and cause them additional expenses or perhaps even force them out of business. If competition is injured, a vertical merger can also cause antitrust concerns.

Vertical Merger

A merger between a firm and a supplier or distributor.

A conglomerate merger occurs when one firm joins with another that is not a competitor, supplier, or distributor. The joining of a steel wire manufacturer and a large beverage company would be a conglomerate merger, as would be the combining of a publishing company and a chain of retail clothing outlets.

Conglomerate Merger

A merger between a firm and another firm that is not a competitor, supplier, or distributor.

Conglomerate mergers can have anticompetitive effects because of what is known as the “deep pocket.” For example, a large, profitable hotel chain might acquire one of several small competing candy companies. As a result of the acquisition, the candy company could receive financial help from the hotel chain's deep pocket full of money for spending on such things as advertising, expansion of facilities, and a larger sales staff. With the help of this money, the candy company could increase its sales and share of the market at the expense of its rivals who do not have comparable financial resources with which to compete.

In the spring of 2002, Sears purchased Lands' End, the mail-order retailer, giving Sears the right to sell Lands' End clothing in its stores. Lands' End had been one of the largest catalog retailers in the country, along with J.C. Penney, Spiegel, and L.L. Bean. In your opinion, was this merger horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate?

Application 14.2, “Cases Involving the Clayton Act and Its Amendments,” presents facts and rulings from classic, landmark court cases on tying arrangements, price discrimination, and mergers. Can you explain how competition would have been injured in each of these cases?

Antitrust Penalties Violations of the antitrust laws can result in one or more of four types of penalties, depending on the offense and who is bringing the suit. The penalties include imprisonment for up to 10 years, fines as large as $1 million per offense for individuals and $100 million per offense for corporations, structural remedies, and triple damages.

APPLICATION 14.2

CASES INVOLVING THE CLAYTON ACT AND ITS AMENDMENTS

CASES INVOLVING THE CLAYTON ACT AND ITS AMENDMENTS

Tying Arrangements: International Business Machines Corp. v. United States (1936) This is an appeal … of a decree of a District Court [enjoining IBM] from leasing its tabulating and other machines upon the condition that the lessees shall use with such machines only tabulating cards manufactured by [IBM], as a violation of §3 of the Clayton Act….

[IBM's] machines and those of Remington Rand, Inc., are now the only ones on the market which perform certain mechanical tabulations and computations … by the use in them of cards upon which are recorded data….

To insure satisfactory performance by [IBM's] machines it is necessary that the cards used in them conform to precise specifications as to size and thickness, and that they be free from defects … which cause unintended electrical contacts and consequent inaccurate results. The cards manufactured by [IBM] are electrically tested for such defects.

[IBM] leases its machines for a specified rental and period, upon condition that the lease shall terminate in case any cards not manufactured by [IBM] are used in the leased machine….

[IBM's] contentions are that its leases are lawful [partly because their] purpose and effect are only to preserve to [IBM] the good will of its patrons by preventing the use of unsuitable cards which would interfere with the successful performance of its machines….

[It appears] that others are capable of manufacturing cards suitable for use in [IBM's] machines….

Ruling [IBM] is not prevented from proclaiming the virtues of its own cards or warning against the danger of using, in its machines, cards which do not conform to the necessary specifications, or even from making its leases conditional upon the use of cards which conform to them. [S]uch measures would protect its good will, without the creation of monopoly or resort to the suppression of competition. [Case decided against IBM.]

Price Discrimination: Volvo Trucks North America, Inc. v. Reeder-Simco GMC, Inc. (2006) Reeder-Simco GMC, Inc. (Reeder), an authorized dealer of heavy-duty trucks manufactured by Volvo Trucks North America, Inc. (Volvo), generally sold those trucks through an industry-wide competitive bidding process, whereby the retail customer describes its specific product requirements and invites bids from dealers it selects based on such factors as an existing relationship, geography, and reputation. Once a Volvo dealer receives the customer's specifications, it requests from Volvo a discount or “concession” off the wholesale price. Volvo decides on a case-by-case basis whether to offer a concession. The dealer then uses its Volvo discount in preparing its bid; it purchases trucks from Volvo only if and when the retail customer accepts its bid. Reeder was one of many regional Volvo dealers…. In the atypical case in which a retail customer solicited a bid from more than one Volvo dealer, Volvo's stated policy was to provide the same price concession to each dealer. In 1997 … Reeder learned that Volvo had given another dealer a price concession greater than the discounts Reeder typically received.

Reeder, suspecting it was … [a dealer] Volvo sought to eliminate, filed this suit under … § 2 of the Clayton Act, as amended by the Robinson-Patman Act … alleging that its sales and profits declined because Volvo offered other dealers more favorable price concessions.

Ruling A manufacturer may not be held liable for … price discrimination under the Robinson-Patman Act in the absence of a showing that the manufacturer discriminated between dealers competing to resell its product to the same retail customer. The act does not reach the case Reeder presents. It centrally addresses price discrimination in cases involving competition between different purchasers for resale of the purchased product. Competition of that character ordinarily is not involved when a product subject to special order is sold through a customer-specified competitive bidding process.

Horizontal Mergers: United States v. Philadelphia National Bank et al. (1963) [The Philadelphia National Bank and Girard Trust Corn Exchange Bank] are the second and third largest of the 42 commercial banks in the metropolitan area consisting of Philadelphia and its three contiguous counties, and they have branches throughout that area. [The banks'] boards of directors approved an agreement for their consolidation…. After obtaining reports, as required by the Bank Merger Act of 1960, from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Attorney General, all of whom advised that the proposed merger would substantially lessen competition in the area, the Comptroller of the Currency approved it. The United States sued to enjoin consummation of the proposed consolidation, on the ground … that it would violate §7 of the Clayton Act.

Ruling … The proposed consolidation … would violate §7 of the Clayton Act…. The consolidated bank would control such an undue percentage share of the relevant market … and the consolidation would result in such a significant increase in the concentration of commercial banking facilities in the area … that the result would be inherently likely to lessen competition substantially….

Sources: International Business Machines Corp. v. United States, 298 U.S. 131 (1936), pp. 132–134, 139, 140; Volvo Trucks North America, Inc. v. Reeder-Simco GMC, Inc. 546 U.S. 164 (2006), pp. 164, 165; United States v. Philadelphia National Bank et al, 374 U.S. 321 (1963), pp. 321, 322.

APPLICATION 14.3

ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL

ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL

There's a story told about Bob, a sales representative, who was having dinner at an annual business convention with several friends who work for companies that compete with his company. Shortly into the meal, one of the diners mentioned that his company was about to drop the price on a product that all the companies represented at the table sell. On hearing this, another diner said that her company was also going to drop its price. Discussion about the potential price drop began to lead the conversation to potential “spot” dropping, which is where companies stay away from dropping prices in each other's largest sales territories.

This turn in the conversation is when Bob, reaching for a roll, knocked over his full glass of water—soaking his shirt and pants. Everyone at the table laughed, Bob waved his hands in feigned embarrassment, said good night to everyone as he got up, and left. As it turns out, Bob knocked the water over on purpose because he saw that the conversation at the table was turning to price fixing, which is an unquestionable antitrust violation. Bob wanted it very clear in everyone's memory that he was not there as the conversation went on.

Anyone who has been involved in an antitrust proceeding would likely say that Bob did exactly the right thing because the stress created by an antitrust violation accusation can be personally devastating. First, there is the financial stress: If found guilty, a person could face a fine of $1 million per offense—not per suit filed. So if, for example, there were four charges listed in a suit, a person found guilty of each of the charges might face a fine of $4 million. And, we're talking about an individual, not a company. In addition to fines, there is the cost of retaining defense counsel. And, there is reason to expect that an employer might not come to an employee's aid; it might be in the employer's best interest to fire an employee, saying, “Wait, he did this, not us.”

Another added stress of an antitrust accusation is the possibility of a prison sentence and all that an incarceration implies. A guilty individual could be looking at up to 10 years in either a minimum or maximum security prison, depending on where the prison system sends the guilty person.

Even if a person is not named as a defendant, the mere possibility of being named a defendant in an antitrust suit can take over one's life. The government typically never tells a target when its investigation has concluded, so a person can live under a cloud of stress and suspicion whether or not he or she is actively under investigation.

There is also the reality that once an indictment is issued, the ongoing investigation and litigation can last for years. Over this time, the accused's friends and coworkers might be interviewed, and there may be requests for mountains of documents by, say, the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice.

The long and short of it is that the antitrust laws should be taken seriously. Violations have the potential to affect personal finances and emotional and physical stress with additional destructive effects on a defendant's family and friends.

Structural remedies involve preventing two or more firms from merging, or breaking an offending firm into two or more unrelated units. Preventing firms from merging is appropriate where a proposed merger would significantly reduce competition in violation of the antitrust laws. In this situation, competition can be promoted by disallowing the merger and requiring the companies to remain separate. Breaking up an offending firm might be used where a single firm has been found guilty of monopolizing a market. Here the monopoly could be ended by separating one or more of the company's divisions into independent units. At one point in the highly publicized government antitrust suit against Microsoft in 1999, breaking the company into two separate entities was given serious consideration.

With triple damages, an injured party can, under certain conditions, collect three times its damages from the offending firm. Suppose it was proven in a court suit that over the last 3 years Company B lost $90 million in profit because of an antitrust violation committed by Company A. On the basis of this, the court could require Company A to pay Company B three times $90 million, or $270 million, in damages.

Application 14.3, “Antitrust Enforcement Up Close and Personal,” looks at how the possibility of being named a defendant in an antitrust suit can have a significant impact on a person's life.

GOVERNMENT REGULATION

In our daily lives, we are much more likely to be affected by government regulation, another way in which government plays a role in the market process, than by the antitrust laws. Government regulation refers to participation by the federal and state governments, through agencies and commissions, in business decision making. Actions of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and state utility commissions are just a few examples of government regulation.

Government Regulation

Government participation, through agencies and commissions, in business decision making; may be industry regulation or social regulation.

In some cases, government regulation involves direct participation in specific aspects of a company's operations: The company's product price, the markets it serves, and other decisions must be approved by a regulatory commission before they can be implemented. In other cases, government regulation involves indirect participation in business operations through setting standards for firms to follow. These standards could apply to safety, health, the environment, and other areas. The Food and Drug Administration, for example, sets purity and safety standards for food and drugs, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets pollution standards.

While the antitrust laws are directed at the relationships between businesses and the degree of competition in specific markets, regulation is concerned with the interests of particular groups in the economy. For example, some regulation is aimed at protecting the consumer, some at labor, and some at the general public.

Government regulation can be divided into two basic types: industry regulation and social regulation. The first type involves regulation of businesses in a particular industry. In the United States, the railroad, electric power, gas distribution, and other industries have been subject to this type of regulation. Generally, industry regulation is direct: Government plays an important role in determining price, profit, and other aspects of the firms' operations.

With social regulation, a regulatory body deals with a particular problem common to businesses in different industries. The commissions with authority over job discrimination (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission), consumer product safety (Consumer Product Safety Commission), and protection of workers' safety and health (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) are examples of agencies that carry out this type of regulation. Much social regulation is indirect and involves setting standards for businesses to follow. Social regulation is often more familiar to us than industry regulation because more resources are devoted by the federal government to social regulation. Estimated federal spending on social regulation in 2011 was $50.4 billion, as compared to $9.1 billion for industry regulation.11

Approximately 70 regulatory agencies exist at the federal level. Table 14.1 lists these in chronological order. Notice that a large number of regulatory agencies was created in the early 1970s. Although historically we associate the Great Depression and the New Deal era with the growth of regulation, the number of federal agencies that originated in the 1970s was nearly double the number created during the 1930s.

TABLE 14.1 Chronology of Federal Regulatory Agencies

Regulatory agencies have been formed throughout the history of the economy, with a large number created in the 1930s and 1970s.

Sources: Ronald J. Penoyer, Directory of Federal Regulatory Agencies—1982 Update, Center for the Study of American Business, Formal Publication Number 47 (St. Louis: Washington University, June 1982), pp. 43–48; Paul N. Tramontozzi and Kenneth W. Chilton, U.S. Regulatory Agencies under Reagan: 1980–1988, Center for the Study of American Business, OP 64 (St. Louis: Washington University, May 1987), pp. 15–24; Melinda Warren and Kenneth W. Chilton, Regulation's Rebound: Bush Budget Gives Regulation a Boost, Center for the Study of American Business, OP 81 (St. Louis: Washington University, May 1990), pp. 15–18, 23, 24; Melinda Warren, Mixed Message: An Analysis of the 1994 Regulatory Budget, Center for the Study of American Business, OP 128 (St. Louis: Washington University, August 1993), pp. 15–17, 27, 28; Melinda Warren and Barry Jones, Reinventing the Regulatory System: No Downsizing in Administration Plan, Center for the Study of American Business, OP 155 (St. Louis: Washington University, July 1995), p. 26; Federal Regulatory Directory, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1990), pp. 445, 507; 10th ed., 2001, pp. 7, 137, 141, 311, 320, 339, 369, 392, 423, 446, 483, 669, 674; 11th ed., 2003, pp. 459, 500, 504, 529, 536, 541, 590, 612, 628, 652, 682, 689; 13th ed., 2008, pp. 305, 353, 488, 506, 516, 579, 647; 14th ed., 2010, p. 341; U.S. Department of Labor, http://www.dol.gov/dol/pwba.

The Structure of Regulation

How does regulation come about? First of all, a particular industry or a specific problem is under federal or state regulation depending on whether interstate or intrastate commerce is involved. Federal agencies have jurisdiction over interstate commerce, and state commissions regulate intrastate commerce. For example, the rates charged by utility companies, such as your electric power company, that serve customers within a particular state are under the regulatory jurisdiction of a state public utility commission. Federal regulatory agencies, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), are established by Congress to regulate activities that cross state lines.

There are several interesting points to understand about these agencies.

- The enabling legislation (legislation that creates the agency) is general. It contains an overall mandate, and specifies the structure of the agency and other important information pertaining to its operation.

- When a regulatory agency is established, it is given the power to carry out the general mandates stated in the enabling legislation. To do so, the agency may make detailed rules and regulations that businesses under its jurisdiction must follow. For example, if the mandate is airline safety, the agency can establish detailed rules regarding air personnel qualifications, airplane inspections, equipment, and such.

- An agency has the power to enforce its own rules and regulations and to punish those who do not comply. Companies that choose to dispute their treatment by an agency may appeal their case to a court of law.

As Table 14.1 shows, some regulatory agencies are established as independent bodies governed by commissioners who are appointed to oversee the operations of the agency, while others are created as part of an existing department (such as the Department of Commerce) and are headed by an administrator within that department. For example, the Federal Reserve system is an independent body headed by an appointed board of seven governors, whereas the Mine Safety and Health Administration is within the Department of Labor and headed by one of its Administrators. State public utility commissions are usually headed by commissioners who are either elected or appointed by the governor.

Industry Regulation

Firms in certain industries, such as the railroad, natural gas, and electric power industries, are subject to industry regulation. This type of regulation deals with pricing, entry of new sellers into the market, extension of service by existing sellers, the quality and conditions of service, and other matters. In other words, some of the decision-making ability of a business in a free market does not exist for this type of regulated firm.

Industry Regulation

Regulation affecting several aspects (such as pricing, entry of new sellers, and conditions of service) of the operations of firms in a particular industry.

In some regulated industries the firm itself is not free to independently choose or alter the price it charges for its product. Instead, it must seek approval from its regulatory agency to raise or lower its price. For example, privately-owned water companies generally must obtain state government approval before they change their rates. Also, in many regulated industries, new firms cannot begin operation unless they receive permission or a license from that industry's regulatory body. Sewer, water, electric, and other utility companies cannot be initiated at will.

Firms already in existence may need to get permission to abandon service or to extend or alter current services. For years the railroads were not permitted to drop un-profitable passenger routes, and a water company cannot simply cut off service to a university because the company disagrees with political statements made by some students and professors. These firms may also be subject to a host of other regulations, such as on the quality of the product offered for sale (for example, chemicals permitted in the water supply) and safety.

Justifications for Industry Regulation Two reasons are frequently cited for industry regulation:

- an economic justification, and

- the public interest.

Efficiency considerations underlie the economic justification for regulation. Quite simply, for some products it is more efficient (less costly) to have the entire output in a market come from one large producer rather than from several smaller producers. In these cases, a natural monopoly exists in the market.12 Water companies are good examples of natural monopolies: It would be quite inefficient and complicated to have several water companies, each with its own pipes and valves running under streets, serving an area.

Natural Monopoly

A market situation where it is; more efficient (less costly) to have the entire output of a product come from one large producer rather than from several smaller producers.

Natural monopolies are the result of strong economies of scale in production and distribution. With economies of scale, which were introduced in Chapter 12, a seller's long-run unit or average total cost falls as its output increases. Economies of scale enable a firm to profitably use highly specialized and efficient equipment and personnel and to take advantage of other benefits due to size.

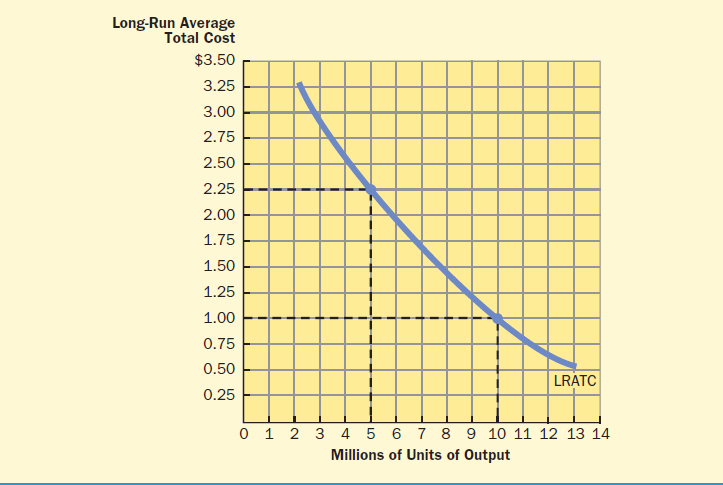

The benefits of a natural monopoly are illustrated in Figure 14.1. Here we have the downward-sloping region of a long-run average total cost (LRATC) curve, which shows that, because of economies of scale, as the level of output increases, the unit or average cost of producing that output falls. Suppose that 10 million units of the output in Figure 14.1 would serve the whole market. If one firm produced the entire amount, the cost per unit would be $1; if two firms each supplied half of the market, or 5 million units, the cost per unit would be $2.25. The total cost to serve the market by one seller is $10 million, considerably less than the total cost of $22.5 million with two sellers equally sharing the market. Thus, significant economies of scale can lead to a natural monopoly where it is more efficient to have one seller rather than several in a market.

Some industries have significant economies of scale, particularly electric power, water, and others where firms depend on large costly plants and equipment (generators, power plants, water treatment facilities, and so forth) to be efficient. By having one large company that can spread these high capital costs over a larger output, the cost per unit is considerably less. Can you explain how economies of scale might affect production costs for natural gas companies?

Unfortunately, natural monopolies create a dilemma for the consumer. On the one hand, because of economies of scale, buyers benefit from lower unit costs when dealing with one seller. But on the other hand, as the only seller in the market, the firm could abuse its monopoly power. Regulation that allows only one firm in the market, while at the same time placing the firm's operations under detailed scrutiny by a public authority so that it cannot unreasonably exploit its monopoly power, resolves this dilemma.

FIGURE 14.1 Economies of Scale and Long-Run Average Total Cost

A natural monopoly exists when economies of scale and the size of the market make the long-run average total cost of production lower with one seller in the market than with several.

Natural monopoly may explain regulation in certain areas of the economy where there are advantages to having only one seller in a market. But what justifies the regulation of airlines, communications companies, railroads, and other firms that produce in industries where there is more than one seller in a market? This regulation is based on the public interest justification.

Public Interest Justification for Regulation

A good or service is so important to the public well-being that its production and distribution should be regulated.

According to the public interest justification, certain types of businesses provide goods or services so important to the public well-being that the public has a right to be assured of their proper operation through regulation. Examples include radio and television companies whose programming can influence public opinion, and transportation firms such as railroads, motor and water carriers, and airlines, that are necessary to keep goods, services, and resources moving.

The public interest justification can be applied in many more situations than the natural monopoly justification. If the argument can be made that the welfare of the public is so affected by the operation of a business that it is desirable to regulate that business, then the public interest justification might be used for regulation. The breadth of this justification was defined in 1934 in one of the most important court decisions on regulation, Nebbia v. New York. In this case, which dealt with the regulation of milk prices, the Supreme Court stated:

It is clear that there is no closed class or category of businesses affected with a public interest…. [A] state is free to adopt whatever economic policy may reasonably be deemed to promote public welfare, and to enforce that policy by legislation adapted to its purpose….13

Simply, this case said that states are allowed to regulate a broad range of businesses in a number of ways in the name of the public interest, provided certain conditions of fairness are met.

Price Regulation One very important aspect of industry regulation is the oversight of the prices, or rates, charged by a regulated company. In many cases a regulated firm, such as a gas or electric or water company, that seeks to raise or lower its rates must appeal to its regulatory commission for permission to do so. And the commission can either approve or deny the request. Typically, rate changes involve formal filings of a request to change a rate, investigations for reasonableness, and hearings before the request is approved or denied.

Regulated firms have two concerns in making rate requests: They must cover their costs, and they must earn enough profit to attract and retain stockholders. Because of these, pricing by regulated firms has traditionally been carried out on a cost-plus basis. With cost-plus pricing the rates, or prices, buyers pay are designed to generate revenues sufficient to cover the costs of operation plus a fair return to those who invest in the business.

Cost-Plus Pricing

Prices are set to generate enough revenue to cover operating costs plus a fair return to stockholders.

But cost-plus pricing may not promote economic efficiency. Permission to collect revenues to cover costs plus a fair return to investors may not provide sufficient incentive to keep costs down, as would happen with competition. As a result, there has been a movement toward incentive regulation, which allows firms subject to price regulation to profit by improving the efficiency of their operations.

Incentive Regulation

A regulatory philosophy that provides incentives for regulated firms to operate efficiently.

A popular form of incentive regulation is price caps, where a maximum is set by a regulatory authority on the price a regulated firm can charge for its product. The company can charge what it wants up to that maximum and, more importantly, retain any additional profit it earns by operating more efficiently. Price caps can lower costs, but firms could also lower their costs by reducing the quality of their services—and not pass those lower costs on to buyers in the form of lower prices.

Price Caps

An incentive system allowing regulated firms to price up to a pre-set maximum and retain additional profit from operating more efficiently.

Social Regulation

The type of regulation that generates the most discussion and controversy because it is closest to our lives is social regulation. Social regulation is aimed at correcting a problem, such as pollution, or at protecting a group in the economy, such as workers or consumers. Rather than focusing on a single industry, social regulation applies to all firms that are affected by the mandate of the regulatory body, regardless of the industry.

Social Regulation

Regulation aimed at correcting a problem or protecting a group; not limited to a specific industry.

Social regulation does not directly intervene into a company's price, profit, and other related decisions. (Although complying with social regulation can raise a firm's costs and affect its prices and profit.) Instead, it focuses on setting and enforcing standards concerning products, employees' working conditions, and other matters that could be harmful to the general public. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is concerned with worker safety and working conditions and is a good example of an agency dealing with social regulation.

TABLE 14.2 Some Social Regulatory Agencies

Much of the effort of agencies concerned with social regulation is directed toward protecting consumers, workers, and the environment.

| Protecting Consumers |

| Consumer Product Safety Commission |

| Food and Drug Administration |

| Drug Enforcement Administration |

| Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration |

| Food Safety and Inspection Service |

| National Transportation Safety Board |

| Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives |

| Federal Aviation Administration |

| National Highway Traffic Safety Administration |

| Protecting Workers |

| Mine Safety and Health Administration |

| National Labor Relations Board |

| Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| Employment Standards Administration |

| Labor-Management Services Administration |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission |

| Protecting the Environment |

| Environmental Protection Agency |

| Office of Surface Mining |

| Council on Environmental Quality |

| Army Corps of Engineers |

| Fish and Wildlife Service |

Source: Melinda Warren and Barry Jones, Reinventing the Regulatory System: No Downsizing in Administration Plans, Center for the Study of American Business, OP 155 (St. Louis: Washington University, July 1995), pp. 23–24; Federal Regulatory Directory, 11th ed. (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 2003), pp. 822–858.

Table 14.2 lists some of the federal agencies responsible for social regulation, categorized according to the group each protects (the consumer, the worker, the environment). Notice that some of the agencies listed in the table affect a broader range of firms and industries than do others. For example, how many industries can you name that might be affected by a ruling of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration? How does this compare with the number that could be affected by a ruling of the Environmental Protection Agency?

It is more difficult to summarize the functions of social regulation than industry regulation because social regulation is so diverse: Consider the differences between the purposes of the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the National Labor Relations Board. However, some generalizations can be made about social regulation. First, as we noted earlier, much more is spent at the federal level on social regulation than on industry regulation: Approximately 85 percent of the expenditures of the major federal regulatory agencies in 2011 were expected to go to social regulation. Second, the direction of social regulatory spending has changed over the years. In 2000, 37 percent of all federal social regulatory spending went to homeland security and 29 percent went to the environment. In 2009, 55 percent of social regulatory spending was expected to go to homeland security and 16 percent to the environment.14

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

GOVERNMENT AND BUSINESS

GOVERNMENT AND BUSINESS

Below are 10 hypothetical situations concerning business practices. Determine in each situation whether the practice would likely:

- violate the antitrust laws, and if so, which one,

- be subject to industry regulation,

- call for social regulation, and if so, by which federal agency, or

- call for no government intervention at all.

- Several firms located along a major river find that the river provides an easy method for disposing of toxic chemicals from production.

- The purchaser of a large amount of carpeting that has been specially cut by the seller for installation in an office complex is demanding a refund after the purchaser mistakenly ordered the wrong color.

- The purchaser of a home appliance is injured when properly using the product because it was poorly designed.

- Two competing manufacturers of a popular consumer product that currently sells for $14 per unit agree that their prices will never fall below $10.

- After discussing developments in the world grain market, two small farmers agree that now is the time to sell their corn if they want to get the best price.

- A regional electric company would like to eliminate its service to a small village of 300 people because the service is losing money.

- The theater chain showing 60 percent of the films in a major city wants to acquire the second largest chain, which shows 20 percent of the films in the city.

- A manufacturer charges $30 per unit to buyers who purchase directly from its warehouse and $35 per unit to buyers who want to pay the additional cost of having the product packaged and shipped to them.

- A local natural gas distribution company decides to double its charge to residential users in order to increase its profits.

- A major supermarket chain cuts prices below cost in three cities until some of its smaller competitors go out of business.

Answers can be found at the back of the book.

Test Your Understanding, “Government and Business,” lets you practice distinguishing among activities that might call for antitrust enforcement, industry regulation, social regulation, or no government intervention at all.

The Performance of Regulation

The spectacular growth of regulation in the 1970s came to an end toward the end of that decade. Concern over the performance of regulation and its effects on business costs and the economy in general brought about an interest in deregulation. Deregulation of the airline, trucking, natural gas, banking, telephone, and other industries came quickly.

Deregulation

A reduction in government regulatory control of the economy.

Proponents of deregulation, then as well as now, believe that in many instances the costs of regulation outweigh its benefits to society. Supporters of regulation hold the opposite view. Up for Debate, “Has Our Enthusiasm for Regulation Gone Too Far?,” concerns a case where regulation became more stringent: the tightening of air pollution standards by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1997. What are the costs and benefits of stricter standards, and what is your assessment of the arguments on each side of this issue?

UP FOR DEBATE

HAS OUR ENTHUSIASM FOR REGULATION GONE TOO FAR?

HAS OUR ENTHUSIASM FOR REGULATION GONE TOO FAR?

Issue In 1997 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued stringent new air quality standards for ground-level ozone (soot and smog). This was the first major revision of the Clean Air Act since 1990. The EPA estimated annual health benefits from the higher standards between $58.1 billion and $120.5 billion, and annual costs of compliance between $6.6 billion and $8.5 billion by the year 2007. Paying the costs to meet these standards places a burden on businesses. Has our enthusiasm for regulation gone too far?

Yes Our enthusiasm for regulation has gone too far. The 1997 EPA standards set goals that may be unattainable. With the new standards, over three times as many counties were out of compliance than under the previous standards. Meeting the new standards—even if possible—will cost local governments and businesses tens of billions of dollars and affect the prices consumers pay, jobs, and the viability of small businesses. In setting standards, regulatory agencies should be paying greater attention to the costs those standards will impose on businesses and communities.

Further, the alleged health benefits from the higher standards should be questioned. Ozone may have short-term health effects, but the effects are reversible, and a clear case has not been made about its longer-term effects.

No Our enthusiasm for regulation has not gone too far. Admittedly, under the new standards many more counties and their businesses were out of compliance, and it is very costly for them to come into compliance. But individuals have long had to incur substantial out-of-pocket and other costs because they live in communities where air pollution is a problem.

The effects of the new standards on prices, jobs, and small businesses are not clear. The standards may simply force businesses in violation to find more efficient ways to operate. Competition may keep prices from rising, more efficient techniques may create new jobs, and typically small businesses are not the principal offenders.

The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to ignore costs when setting standards. When it comes to human health and the quality of life, this is as it should be.

Based on: Kenneth W. Chilton and Stephen R. Huebner, “New Rules Would Be Costly, Have Limited Health Benefits,” and Ken Midkiff, “Proposed Standards Are Based on Careful Scientific Study,” both in “What Price Clean Air?” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1996, p. 3B; John M. Broder, “Deregulation: Crusade Shifts to Compromise,” The New York Times, January 31, 1997, p. C3; Environmental Protection Agency, “EPA's Decision on New Air Quality Standards,” http://www.epa.gov/ttn/oarpg/naaqsfin, September 15, 2005.

The growth in global markets and international economic activity is also an important area of regulatory discomfort. Regulation and antitrust policies tend to be national in scope. Barring a special international agreement, U.S. policies usually will not affect foreign firms doing business in foreign markets. As a result, some believe that U.S. firms are at a disadvantage when competing with foreign firms that face less or little regulation at home or are not subject to the antitrust laws that firms in the United States face. For example, one issue that repeatedly surfaces is the U.S. labor laws that forbid child labor and protect U.S. workers from potential harm at work. While these regulations clearly protect children and workers, they can also raise costs for U.S. businesses. Countries that permit child labor and have few laws protecting their workers can produce and sell goods at a lower price.

The questions created by nationally focused antitrust and regulatory policies are becoming increasingly important as economic activity becomes more global. And, the debates over the costs and benefits of government intervention are becoming more complicated as a wider array of values and traditions from different cultures are brought forward.

Summary

- Government intervenes in the operation of markets in the U.S. economy in two important ways: antitrust enforcement and regulation. This intervention occurs to ensure competition in markets, take advantage of efficiencies resulting from large-scale operations, and provide security to specific groups.

- Antitrust laws are concerned with the relationships between rival firms and the level of competition in a market. They are designed to promote market forces by attacking monopolization, attempts to monopolize, and combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade. This type of government intervention is carried out at the federal and state levels, and it depends heavily on the judicial system. Antitrust suits can also be filed by private parties.

- There are five major federal antitrust laws: the Sherman, Federal Trade Commission, Clayton, Robinson-Patman, and Celler-Kefauver acts. The Sherman Act Section 1 condemns combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, and Section 2 condemns monopolization. Combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade may be either per se or rule of reason violations. Monopolization cases depend largely on the actions and market share of the accused firm.

- The Federal Trade Commission is empowered to prevent unfair methods of competition, including antitrust violations. The Clayton Act condemns exclusionary practices, interlocking directorates, price discrimination, and mergers, where the effects of these activities are anticompetitive. The price discrimination and merger provisions of the Clayton Act were amended by the Robinson-Patman and Celler-Kefauver acts, respectively.

- Penalties facing those found guilty of violating the antitrust laws include imprisonment, fines, structural remedies, and triple damages.

- Regulation is participation by federal and state government agencies and commissions in business decision making. Regulation is aimed at controlling certain industries and problem areas, and at protecting certain groups in the economy. In some instances a regulatory agency directly participates in a company's pricing and other decision making; in others the regulation is indirect and carried out through setting standards.

- Regulatory authority is under federal jurisdiction for interstate commerce and under a state agency for intrastate commerce. Federal agencies can be independent or attached to departments such as the Department of Labor.

- Regulation can be divided into industry and social regulation. Industry regulation involves government participation in pricing, output, profit, and other decisions of firms in certain industries, such as the electric and gas distribution industries. Social regulation includes such activities as setting and enforcing standards and is not limited to firms in any single industry.

- Two frequently cited reasons for industry regulation are the existence of a natural monopoly due to economies of scale and effects on the public interest from the operation of certain businesses. An important aspect of industry regulation is the setting of prices. This has traditionally been done on a cost-plus basis, where prices are designed to generate enough revenue to cover expected costs plus a fair return to investors. More recently, incentive pricing schemes, such as price caps, have been given greater attention.

- Social regulation focuses mainly on protecting consumers, workers, and the environment. Much more is spent on social regulation than industry regulation.

- There is an ongoing debate over the optimal levels of regulation and, given the growing globalization of economic activity, concern over the impact of nationally focused antitrust enforcement and regulation.

Key Terms and Concepts

Antitrust laws

Monopolization and attempts to monopolize

Combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade

Sherman Act

Per se violations

Price fixing

Territorial division

Tying arrangement

Exclusive dealing arrangement

Rule of reason violations

Trade association

Joint venture

Federal Trade Commission Act

Clayton Act

Interlocking directorates

Robinson-Patman Act

Price discrimination

Celler-Kefauver Act

Horizontal, vertical, and conglomerate mergers

Government regulation

Industry regulation

Natural monopoly

Public interest justification for regulation

Cost-plus pricing

Incentive regulation

Price caps

Social regulation

Deregulation

Review Questions

- What do Section 1 and Section 2 of the Sherman Act condemn? What specific acts could be considered violations of Section 1? What are the main factors the courts consider when judging whether a firm has committed a Section 2 violation?

- What is the difference between a per se violation of the antitrust laws and a rule of reason violation? Why are some business practices considered per se violations while others are not?

- What activities are prohibited by the Clayton Act, the Robinson-Patman Act, and the Celler-Kefauver Act?

- In what respects are industry and social regulation similar and in what respects are they different?

- What is a natural monopoly and how is it related to economies of scale? What sort of dilemma does the combination of efficiency and monopoly power create for the consumer and the policymaker?

- Explain the difference between the natural monopoly justification for regulation and the public interest justification. Why is the public interest justification applicable to a wider range of firms than the natural monopoly justification?

- What is cost-plus pricing and how can it lead to inefficient performance by a regulated firm? What are price caps and how can they improve efficiency?

- Provide some examples of social regulatory agencies and identify the main groups or areas that each protects.

Discussion Questions

- Horizontal mergers, vertical mergers, conglomerate mergers, price discrimination, and interlocking directorates may or may not be anticompetitive. For each of these five activities, describe a set of circumstances where you think the effect would be anticompetitive and where it would not be anticompetitive.

- The antitrust laws are designed to control the growth of monopoly power in specific markets. What are some economic reasons for concern over monopoly power? Are there any noneconomic reasons for wanting to control this power?

- Antitrust laws reinforce the operation of free markets, while regulation replaces free market forces with an authoritative body. How do you explain that certain economic problems are dealt with by strengthening market forces while others are dealt with by replacing the market mechanism with regulatory authority?

- Suppose legislation is passed to repeal the major federal antitrust statutes. How do you think such a repeal would affect competition? Would competition between sellers continue much the same as before the repeal? Would there be a blossoming of monopoly power? Would something else occur?

- Assume that the production of a particular good is accompanied by significant economies of scale. Would you recommend vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws to ensure that no one firm could monopolize the production of this product, or would you allow a monopoly to form and then subject it to industry regulation? Justify your answer.

- There is concern about the costs and benefits of regulation. What costs and benefits might be created if the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission were abolished? In your opinion would we be better off without the agency than with it?

- What complications are created for businesses and the economy in general as a result of the administration of regulatory and antitrust policies in an increasingly global environment?

Critical Thinking Case 14

EMINENT DOMAIN: IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST OR NOT?

Critical Thinking Skills

Weighing the merits of competing arguments

Identifying consequences of policy choices

Economic Concepts

Social regulation

Public interest justification for regulation

Cost-benefit analysis

In July 2005 the U.S. Supreme Court, in a closely watched 5-to-4 decision, ruled that a local government can condemn and seize someone's property and turn it over to a private contractor to build a development that will strengthen the local economy. The case, Kelo v. New London, was brought by a New London, Connecticut, homeowner whose property was to be condemned and transferred by the city to a developer, who would take it and other adjacent properties, tear down the houses and other buildings, and construct a hotel and office complex in their place.

The issue at the foundation of this court decision is a long-standing practice called “eminent domain,” where a government unit buys someone's property (often against the seller's wishes) and then uses it in the public interest. Usually, “using property in the public interest” is understood to mean invoking eminent domain for a public project like a highway or flood protection. But in this case, the property was to go to a private developer who would benefit from the project.

The reaction to this court decision was quick and furious. Within a few weeks, bills were introduced in the U.S. House and Senate and over half the state legislatures to limit the use of eminent domain for the benefit of private developers.

Arguments can be made both in support of and opposition to the Supreme Court's decision. In support of the decision, eminent domain might be necessary to encourage private developers to restore declining, at-risk urban areas to healthy, productive places. In addition to the benefit of a revitalized area, construction-related jobs would be created, leading to more spending that benefits everybody. And if handing the property to a private developer leads to more tax revenue for the city than before the property was condemned, then the public interest is further served.

On the other side is the fear that all private property will now be fair game for seizure in behalf of a developer if it can be argued that the developer will contribute more to the area's economic growth than the current owner. There is also the issue of who benefits and who loses from this broader freedom to seize property. Can developers with more money and influence than homeowners of average or lower-than-average income come out on top?

There are other concerns: This expanded power to condemn could be abused by local governments desperate to increase economic development. And, there is concern also that the strong and growing resistance to the Supreme Court's decision could lead to the canceling of projects and losses to contractors.