CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To understand that there are several major macroeconomic models with different assumptions that focus on different relationships, and to recognize the historical dimension of macroeconomic theory.

To discuss the fundamental relationships of the classical, new classical, Keynesian, new Keynesian, and monetarist schools of thought.

To describe the classical aggregate demand–aggregate supply model and its conclusions.

To understand the basic relationships in the Keynesian model and the policy implications of the model.

To explain the new classical model and its policy implications.

In Chapter 5, we discussed macroeconomic fluctuations: The macroeconomy is always expanding or contracting, or in some phase of a business cycle. Production increases and unemployment falls during a recovery, and production decreases and unemployment rises during a recession. The causes of these fluctuations have been pondered for centuries, as have the causes of another major macroeconomic problem: inflation.

The relationship between the amount of total spending in an economy and the economy's levels of production and employment was laid out in Chapter 5. Businesses respond to spending changes by households, other businesses, government, and foreign buyers by increasing or decreasing their levels of production.

The foundation built in Chapter 5 can be used to understand various viewpoints about the macroeconomy and different models that have been developed to explain how it operates. Some important questions can be answered by relying on our Chapter 5 foundation as well as these models. For example, while spending changes may trigger economic fluctuations, what triggers spending changes? Is there a difference in short-run and long-run macroeconomic relationships? Is there a level of activity that an economy automatically seeks?

We begin this chapter with an overview of macroeconomic model building and discuss the components of a model as well as how history has influenced the development of these models. We then introduce some of the major macroeconomic schools of thought—the classical, Keynesian, new classical, new Keynesian, and monetarist schools—and the basic model of each school.

MACROECONOMIC MODEL BUILDING

Much of the work of economists is model building; that is, economists look for explanations for relationships between economic variables or seek answers to why an economic problem or condition occurs. As explained in Chapter 1, model building involves four components: identifying variables, establishing assumptions, collecting and analyzing data, and interpreting conclusions.

Economic theory has an important historical dimension: Searches for explanations of economic problems are often related to historical events. For example, there was significant joblessness during the Great Depression in the 1930s, which gave rise to a need to determine the cause of unemployment and policies to remedy it. One of the great songs of the Depression era, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?,” captures the extreme distress underlying the need to change the direction of the economy.

“Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time.

Once I build a railroad; now it's done. Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once I built a tower, up to the sun, brick, and rivet, and lime;

Once I built a tower, now it's done. Brother, can you spare a dime?”1

The severe inflations of the mid-to-late 1970s and early 1980s brought serious interest in determining the causes of inflation. Beginning in 2008, a deteriorating economy again brought significant interest in economic theory and policy. In addition, the rising role of the Federal Reserve and the bailout of financial institutions brought renewed interest in money and monetarism.

A Warning

Recall that a model examines the relationship between two variables. It is important to keep this in mind as we study the models in this chapter because not all macroeconomic models attempt to explain the same relationships. Rather, they focus on different problems and variables. In this chapter, one model explores the relationship between prices and output, another the relationship between spending and output, and a third the relationship between money and output.

The assumptions, or conditions held to be true, when building a model are important because they underlie the model and affect its conclusions. Assumptions can be influenced by the values of the model builder, and the role of these values in developing assumptions is often overlooked or difficult to identify. For example, if one values free markets, then free markets can become an underlying assumption of a model and in turn become important to policy recommendations that follow from the model. If one values government intervention, then this value can become important to the assumptions of a model and its resulting policy implications.

It is useful for students to identify the variables, assumptions, and data that go into the construction and presentation of a model. The interpretation of the conclusions of the model as well as its policy implications are affected by the choice of each of these parts of the model. This makes it important for students to be able to put models in their proper context in economics as well as in other classes. For example, in the social sciences, conclusions about people's behavior patterns are often based on research done in a model, so it is useful for students to understand how the model's assumptions and data collection affect those conclusions. Knowledge of the cultural setting of a model in sociology, the values of a teller of history, and the data collection method for a political science survey are all important for a fuller understanding of work in these fields.

Application 9.1, “Paying Close Attention to Models: It's Worth the Effort,” provides some additional thoughts about economic model building and the impact of how the story in a model is presented. Can you think of a theory you studied in a social science course, such as psychology, sociology, or political science, that influenced history or the personal beliefs of a large number of people or policymakers?

VIEWPOINTS AND MODELS

Over the years, different models have been developed by economists to explain the operation of the macroeconomy, and different policy prescriptions have been advocated to stabilize the economy. Alternative viewpoints about the macroeconomy often stem from the different assumptions on which the models are formulated. Also, sometimes a viewpoint loses popularity as new data and information provide better explanations of key economic relationships or solutions to problems.

These different macroeconomic theories and the policy prescriptions that follow from them can be better understood by placing them into categories, or “schools of thought.” Several schools of thought are significant to the development of macroeconomic theory. These include the classical, Keynesian, new classical, new Keynesian, and monetarist schools.

Classical Economics

The dominant school of economic thought before the 1930s was classical economics. This school, however, was largely rejected during the 1930s because it could not explain the cause of, or offer a successful remedy for, the prolonged and severe unemployment that developed during the Great Depression. The basic premise of the classical school, which dates from Adam Smith and his book The Wealth of Nations in the late eighteenth century, is that a free market economy, when left alone, will automatically operate at full employment. And, because a free market economy always automatically corrects itself to full employment, there is no need for government intervention to rectify its problems. Adam Smith is one of the economists featured in Application 9.2, “The Academic Scribblers.”

Classical Economics

Popularly accepted theory prior to the Great Depression of the 1930s; says the economy will automatically adjust to full employment.

APPLICATION 9.1

PAYING CLOSE ATTENTION TO MODELS: IT'S WORTH THE EFFORT

PAYING CLOSE ATTENTION TO MODELS: IT'S WORTH THE EFFORT

Working your way through an economic model can be difficult, boring, and time consuming. The problem is that economic models have a significant impact on our lives. It is usually the conclusion of a model that is the starting point for policies that affect so many aspects of how we live, from our jobs to the kinds of things we can afford to buy. So, we should pay close attention to what is in a model.

The importance of economic forces is bluntly stated on the first page of a book by Alfred Marshall that played a major role in opening the door to what we think of as modern economics. Marshall wrote, “[M]an's character has been moulded by his every-day work, and the material resources which he thereby procures, more than by any other influence unless it be that of his religious ideals; and the two great forming agencies of the world's history have been the religious and the economic.”a Stop and think for a moment: These two factors—religion and economics—have played a central role in bringing people together but also in their going to war against each other.

While economic models might be difficult and boring, people (some of whom exert great power) take them very seriously. As John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the twentieth century, put it, “[The] ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”b

Sometimes the take on the story a model tells changes after its assumptions and data are explored in detail. For example, you probably know the story of the three little pigs. One lived in a house built of straw, the second in a house built of sticks, and the third in a house built of bricks. When the wolf came along, he blew down the houses of straw and sticks, but not the house of bricks. The usual moral of the story is that the pig in the brick house put in the effort to build a solid house, and the other two pigs were lazy. But how would the moral of the story change if the first pig worked an 80-hour week in the brick factory to get by and feed his kids, the second pig was disabled by an accident in the brick factory and unable to work, and the third pig was the brick factory owner's son?

What is the moral of the story in this application? The influence of economics is not to be taken lightly, and the models used to extend this influence should be thoroughly examined and understood. While we may not tolerate details well, it is those details of our economic models that tell the real story.

a Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics (London: Macmillan and Co., 1890), p. 1.

b John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1936), p. 383.

The classical economists arrived at their position about the automatic self-correction to full employment because of several assumptions. First, they assumed that supply creates its own demand in a macroeconomy.2 In other words, something that is produced will be bought by someone. As a result, there is no need for concern about operating at less than full employment and production: The goods and services that are produced will all be purchased.

APPLICATION 9.2

THE ACADEMIC SCRIBBLERS

THE ACADEMIC SCRIBBLERS

Adam Smith Adam Smith, considered by many to be the “father” of market economics, or capitalism, was born in 1723 in Scotland. He lived during a time of tremendous change in Britain: The Industrial Revolution brought inventions allowing for more efficient production, factories, a poor working class, the rise of capitalists, and many other economic and social changes.

Smith was a well-known philosopher in his time. At the age of 28, he was offered the Chair of Logic at the University of Glasgow, and later the Chair of Moral Philosophy. The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which he published in 1759, gave Smith recognition as he explored the philosophical question of how people, who are basically motivated by self-interest, consider the moral merits of an action.

Smith's most famous work, The Wealth of Nations, was revolutionary for its time because it represented a movement from mercantilist thinking to the idea that individual decision making would best serve a society's interests. In this text, Smith focuses on the market mechanism and shows how individual self-interest operating through markets provides the greatest good for society. He also discusses the importance of competition in a market system and firmly states that government should not intervene in the market mechanism. It is these assertions that strongly connect Smith to classical economics.

No biography of Smith is complete without mention of his absentmindedness; this extended to late-night walks about his village in his nightclothes, an often-mentioned tale about Smith. Smith, who lived peacefully with his mother in his later years, died at 67.

John Maynard Keynes John Maynard Keynes, probably the most influential economist of the twentieth century, was born in 1883 in England. His father, John Neville Keynes, was an economist and a logician who taught at Cambridge University. John Maynard was well educated, and his first interest was in mathematics. Urging by some distinguished professors sent him in the direction of economics.

Keynes led a full and active life intermingling different careers: a brief stint in the civil service, a lectureship in economics at Cambridge, bursar at Kings College, adviser to various London bankers, and a successful personal financier. His interests were also varied: He had close ties to the colorful Bloomsbury set of intellectuals, married a ballerina, financed a theater group, and had an extensive art collection. An observer of Keynes noted, “He would go out of his way to make something flattering out of what a student had said…. On the other hand, when a faculty member got up [he] simply cut their heads off.”a

Although Keynes is well known for his 1919 book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, which discusses the economics of the Versailles Treaty of World War I, his major work is The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936. This book focuses on Keynes' major contribution—that a market economy's levels of output and employment are the result of the level of aggregate demand. It should be noted that although government interventionist policies are associated with Keynesian economics, Keynes' ideas were rooted in his regard for individualism. The following quote is from The General Theory.

But, above all, individualism, if it can be purged of its defects and its abuses, is the best safeguard of personal liberty in the sense that compared with any other system, it greatly widens the field for the exercise of personal choice. It is also the best safeguard of the variety of life, which emerges precisely from this extended field of personal choice, and the loss of which is the greatest of all losses of the homogeneous or totalitarian state.b

Milton Friedman The face and work of Milton Friedman are familiar to many Americans: He wrote and lectured in a wide variety of places and made appearances on television talk shows. Friedman completed a video series, Free to Choose, that has been seen on public television and in many classrooms, and his accompanying book, coauthored with his wife Rose, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, was on The New York Times best seller list. In 1976, Milton Friedman received the Nobel Prize in economics.

Friedman was born in 1912 in New York to hardworking immigrants. His father died when Friedman was 15, placing additional financial burdens on his mother and causing Friedman to rely on scholarships to obtain an education. He received his undergraduate degree from Rutgers, went to the University of Chicago for graduate study, and earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1946. Friedman eventually returned to an academic post at the University of Chicago, where he remained until 1977.

Milton Friedman's many contributions to economics focused on the importance of money to the operation of the macroeconomy, and he was associated with renewing interest in money and macroeconomic policy. However, he was also known for strongly embracing a free market philosophy and for espousing the view, associated with the Chicago School, that a market economy works best when left alone. In many cases, such as public education, Friedman believed that a competitive market would do a better job and that the government has done more harm than good. Milton Friedman died in 2006.

a William Breit and Roger L. Ransom, The Academic Scribblers, rev. ed. (Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden Press, 1982), p. 67.

b Breit and Ransom, p. 68. Also see John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1936), p. 380.

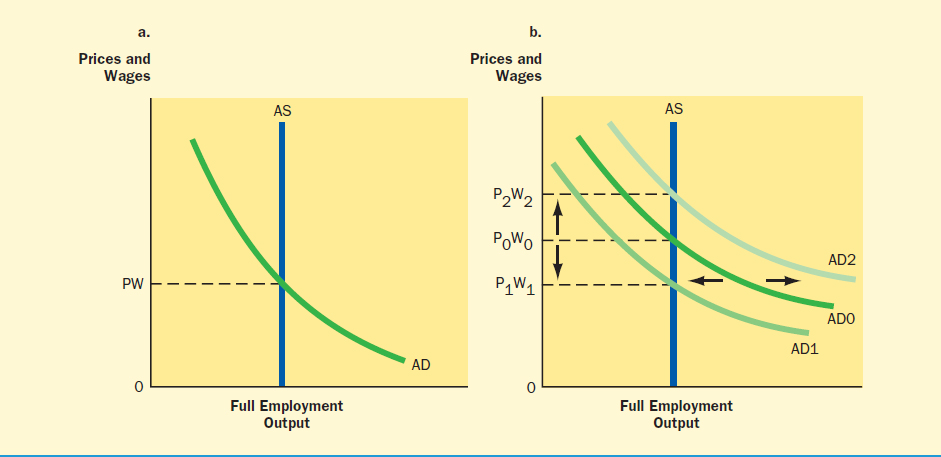

FIGURE 9.1 Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand in Classical Economics

In the classical model, prices and wages adjust in order to maintain a full employment level of output.

A second assumption of the classical economists was that wages and prices are flexible and increase or decrease to ensure that the economy operates at full employment. This assumption is illustrated in Figure 9.1. The perfectly vertical aggregate, or total, supply curve (AS) in Figure 9.1a illustrates an economy producing at the full employment level of output, regardless of whether prices and wages are high or low. The aggregate demand curve (AD) in Figure 9.1a represents the spending plans of households and businesses in the economy. The curve slopes downward to indicate that an inverse relationship exists between prices and wages, and the amount of output demanded. When prices fall (which will also bring wages down in the classical model), households and businesses want to purchase a greater amount of output, and when prices increase, they want to purchase less. In Figure 9.1a, aggregate demand and supply are equal at the full employment level of output with price and wage level PW.

If there is a change in aggregate demand, as illustrated in Figure 9.1b by the decrease or increase in the aggregate demand curve from AD0 to AD1, or AD0 to AD2, respectively, there will be a change in prices and wages that allows the economy to continue to operate at full employment. For example, if initially in Figure 9.1b, aggregate demand were AD0, aggregate supply were AS, and the level of prices and wages were P0W0, the economy would be operating at full employment. If aggregate demand were to decrease and the aggregate demand curve shifted to the left to AD1, less would be demanded than supplied at the original price and wage level (P0W0), and the economy would experience some temporary unemployment. However, according to the classical assumptions, prices and wages would soon fall to P1W1, and the economy would return to full employment. This lower price and wage level would permit full employment at the lower level of demand.

Likewise, if aggregate demand were to increase and the aggregate demand curve shifted to the right from AD0 to AD2 in Figure 9.1b, more would be demanded than could be supplied at the original price and wage level of P0W0. Prices and wages would rise to P2W2, with the economy continuing to operate at full employment. In the classical model, the adjustment to changes in aggregate demand is through changes in prices and wages, not output and employment. Production will seek the full employment level, regardless of changes in demand.

The classical economists also assumed that savings always equals investment: Everything leaked from the spending stream through savings is returned through the investment injection. This equality always occurs, they reasoned, because changes in the interest rate bring savings and investment into equality.

As indicated earlier, classical theory, with its hands-off attitude toward the economy, was largely abandoned in the 1930s when it could not explain the persistence of the Great Depression or offer a solution to the unemployment problem. In its place came Keynesian theory, which advocated managing total demand to attack the problems of unemployment and inflation. Like classical economics in the 1930s, however, Keynesian theory was not wholly successful in explaining the problems of the 1970s when the economy was experiencing high rates of both unemployment and inflation.

Keynesian Economics

The ideas of the British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) form the basis for Keynesian economics. Keynes, one of the best-known economists of the twentieth century, came to the forefront of economics during the 1930s when prevailing classical theory could not provide a satisfactory explanation for the depression that most industrialized nations in the world faced. Keynes focused on the causes and cures for unemployment and low levels of output. His most famous work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was published during the Great Depression.3 Background on Keynes' life and thinking is given in Application 9.2.

Keynesian Economics

Based on the work of John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who focused on the role of aggregate spending in determining the level of macroeconomic activity.

Keynes revolutionized economic thinking by focusing on the role of aggregate, or total, spending in the economy. His major contribution was to link increases and decreases in output and employment with increases and decreases in spending. Keynes rejected the classical notion of an automatic adjustment to full employment, reasoning that an economy's output and employment would improve from less than full employment only if aggregate spending increased. Keynes also believed that the spending gap responsible for recessions and unemployment could be filled by the government.

Keynes introduced the idea that a macroeconomy seeks an equilibrium output level, or that there is a level of output toward which an economy moves. Macroequilibrium could be at a low level of output, which results in unemployment and low incomes, or at a high and healthy level of output. During the Great Depression, conditions were such that the economy was moving toward an equilibrium level that was far from full employment.

Equilibrium in the Macroeconomy An economy is in macroeconomic equilibrium when the amount that all households, businesses, government units, and foreign buyers plan to spend on new goods and services equals the total amount of output the economy is currently producing. At equilibrium there is no tendency for change in the level of economic activity because the planned spending of all buyers is just sufficient to purchase all the goods and services that are produced.

Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Occurs when the amount of total planned spending on new goods and services equals total output in the economy.

TABLE 9.1 Total Output and Total Planned Spending (Trillions of Dollars)

This macroeconomy is in equilibrium at $3.0 trillion, where total output is equal to total planned spending, and injections into the spending stream are equal to leakages.

When the amount that households, businesses, government units, and foreign buyers plan to spend on new goods and services differs from the total output produced, the economy is not in equilibrium, and output, employment, and income will change. If the total planned spending of all buyers is greater than current production, then output, employment, and income will increase, assuming that full employment has not been reached. If the total planned spending is less than current production, then output, employment, and income will fall.

The key to understanding how spending can be more or less than current production is in the role played by inventories. Most businesses intentionally maintain an inventory of their products. When total spending in the economy is greater than current production, inventories begin to fall, signaling a need to increase output levels. When total spending is less than current production, unintentional inventories begin to accumulate, causing businesses to cut back on production.

Inventories

Stocks of goods on hand; can be intentional or unintentional.

Illustrating Equilibrium Table 9.1 illustrates possible levels of total output that a hypothetical economy could produce and the total planned spending of all households, businesses, government units, and foreign buyers that would occur at each level of output at a given point in time. For example, all buyers would purchase $2.5 trillion worth of goods and services at an output level of $2.0 trillion, or $3.5 trillion of goods and services at an output of $4.0 trillion. Total spending increases as output increases because with more output there is more earned income for households to spend.

Notice in Table 9.1 that there is one level of output, $3.0 trillion, where total planned spending equals total output. Here the economy is in equilibrium. At output levels less than $3.0 trillion, planned spending is greater than output; inventories fall, causing businesses to produce more; and the economy expands. At output levels greater than $3.0 trillion, planned spending is less than output; unintentional inventories build up causing businesses to produce less; and the economy contracts toward the equilibrium level of $3.0 trillion.

An important factor determining whether the economy is in equilibrium or expanding or contracting is the relationship between leakages from and injections into the spending stream. (Recall that leakages and injections were discussed in Chapter 5.) When leakages equal injections, the economy is in equilibrium. For example, suppose an economy produces $7 trillion of goods and services, which results in the creation of $7 trillion in income. Assume that from this $7 trillion income, households spend $5 trillion and the rest, $2 trillion, is leaked from the spending stream through saving, taxes, and the purchase of imports. In order to keep the production level unchanged at $7 trillion, or to maintain equilibrium, the entire amount that was leaked must be replaced by injections of an equal amount. That is, $2 trillion in business investment spending, government purchases of goods and services, household spending from transfer payments and borrowing, and/or foreign expenditures on exports must be put into the system.

If the amount that is leaked from the spending stream is greater than the amount injected into the spending stream, the economy will contract. Unintentional inventories will build up, and businesses will respond by cutting back on output and employment. On the other hand, if injections are greater than leakages, the size of the spending stream will increase to a level greater than current output. Intentional inventories will fall and businesses will respond by expanding production, assuming that full employment has not yet been reached.

Observe in Table 9.1 the columns Leakages and Injections. Notice that the economy's injections are $1.5 trillion regardless of the level of output. Because injections are independent of earned income, they do not change as output and income change. Because leakages include saving, taxes, and purchases of imports, leakages are $0 when there is no output or income from which to save, pay taxes, or buy imports, and they increase as output and income increase. Notice in the right-hand column of Table 9.1 that the economy expands when injections are greater than leakages, and it contracts when leakages are greater than injections. At equilibrium they are equal.

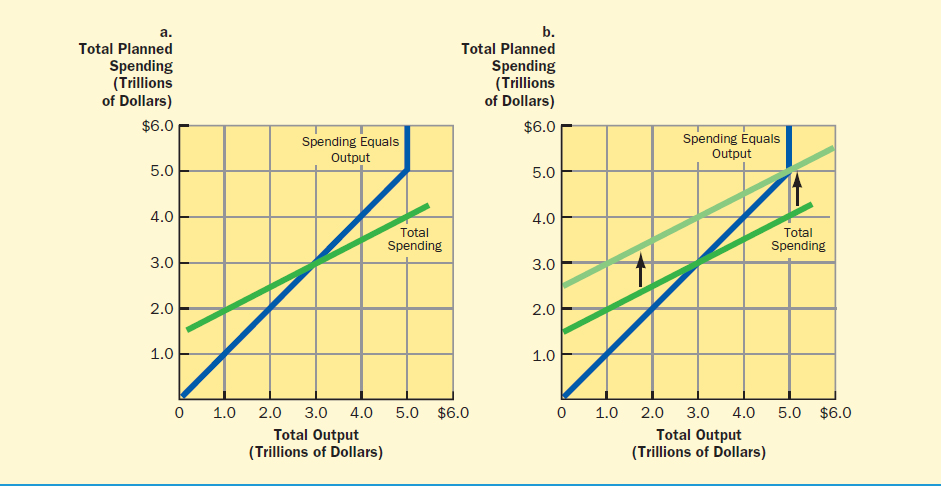

Figure 9.2 illustrates the information given in Table 9.1. Total output is measured along the horizontal axis and total planned spending along the vertical axis. A 45-degree line is also plotted on this graph. Every point on this line matches a level of output with exactly the same level of spending. For this reason, the line is named the Spending Equals Output line.

The numbers from Table 9.1 showing total planned spending at each level of total output are illustrated by the Total Spending line in Figure 9.2. Notice that the Total Spending line crosses the Spending Equals Output line at exactly $3.0 trillion of output, which is the equilibrium level in Table 9.1. At output levels less than equilibrium, the Total Spending line is above the Spending Equals Output line. Because spending is greater than output, output will increase toward equilibrium. At output levels greater than $3.0 trillion, the Total Spending line is below the Spending Equals Output line, causing output to fall toward equilibrium.

The difference between the 45-degree line and the Total Spending line at each level of output is equal to the difference between injections and leakages at that output level. When the Total Spending line is above the 45-degree line, injections are greater than leakages; when it is below, leakages are greater than injections. For example, the Total Spending line is $0.5 trillion above the 45-degree line at an output of $2.0 trillion because, at that output, injections exceed leakages by $0.5 trillion.

Keynesian Policy Prescriptions Based on this model, Keynes pioneered the idea of using government expenditures and taxes to control the level of economic activity. According to Keynes, the appropriate policy prescription for counteracting a recession is to increase aggregate spending. This can be accomplished by increasing government expenditures on goods and services and/or transfer payments, and/or by lowering taxes. In other words, government can pump in the spending necessary to move the economy out of a recession.

FIGURE 9.2 Equilibrium in the Macroeconomy

The macroeconomy is in equilibrium at the output level where the Total Spending line crosses the Spending Equals Output line.

Figure 9.3 illustrates Keynes' ideas about fiscal policy. In the economy in Figure 9.3, full employment would be reached at an output level of $5.0 trillion. Here the Spending Equals Output line becomes vertical to indicate that output cannot exceed $5.0 trillion, even though spending can continue to grow. In Figure 9.3a, the economy is moving toward an equilibrium level of $3.0 trillion, well below the full employment level of $5.0 trillion. In other words, this economy is moving toward an equilibrium with a significant amount of unemployment, or toward a recession.

To reach full employment, additional spending must be injected into the economy. This could be accomplished by increasing government purchases of goods and services, by increasing transfer payments to give households more money to spend, and/or by decreasing taxes, which also gives households more money to spend. Any of these actions could cause total spending to increase, or the Total Spending line to shift upward.

Figure 9.3b shows the result of fiscal policy actions to move the economy to full employment. In this case, government policies have shifted the Total Spending line upward so that the economy will move toward equilibrium at $5.0 trillion rather than $3.0 trillion, and the economy will experience a recovery rather than a recession.

FIGURE 9.3 Changes in Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Government fiscal policy can be used to increase total spending in the economy and move equilibrium to a higher level.

Keynes believed that because an economy does not automatically seek a full employment level of output, it is appropriate from time to time for government to provide the spending boost that is needed. In other words, an upward shift of the Total Spending line could be government induced.

Keynesian economics reached its peak of popularity during the 1960s. In the early 1970s, however, it became a target for attack. Some argued that the problems of the 1970s could not be explained or remedied in Keynesian terms and that wasteful spending by government and increasing federal government deficits were linked to the Keynesian approach to economic policy.

During the 1980s, the political mood favored a movement away from government intervention in the economy, causing further attacks on Keynesian economics and a renewed interest in other approaches to macroeconomic policy, such as monetarism and new classical economics. In more recent years, there has been increased appreciation for, and application of, the fundamentals of Keynesian economics. In 2008, for example, the federal government sent tax rebate checks to qualifying taxpayers to help ward off a possible recession, and in 2009 an economic stimulus program was enacted. However, the substantial rise in the national debt as a result of the automatic stabilizers, a previous tax cut, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the 2008 and 2009 fiscal stimulus programs brought serious criticism over government spending.

New Classical Economics

In the mid-1970s, many of the world's economies began to experience serious inflationary problems. A sudden escalation in the price of oil caused a rapid increase in energy costs, which, in turn, kindled cost-push inflation. For example, fuel costing $17 in 1970 more than doubled in price by 1975 to $36.40 and peaked at $104.60 in 1981. In addition, the tradeoff between price changes and unemployment that was traditionally acknowledged no longer applied. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the U.S. economy experienced stagflation, or high rates of both unemployment and inflation. In 1975, 1980, and 1981, the U.S. economy's rate of unemployment was between 7.1 and 8.5 percent, while the inflation rate was over 9.1 percent.4

Stagflation

Occurs when an economy experiences high rates of both inflation and unemployment.

FIGURE 9.4 Aggregate Demand in the New Classical Model

Aggregate demand in the new classical model is downward sloping and is based on the interest rate, wealth, and foreign trade effects.

These economic problems renewed an interest in exploring the relationship between price levels and output, or in returning to the views of the classical school. As a result, new classical economics was born.

New Classical Economics

A return to the basic classical premise that free markets automatically stabilize themselves and that government intervention in the macroeconomy is not advisable.

Many of the basic elements of the classical school can be found in new classical economics. These include an underlying assumption of a free market economy, a model that focuses on output and prices, a downward-sloping aggregate demand curve, and an emphasis on flexible prices. Also, while the classical economists said that the economy tends to operate at full employment, the new classical economists assert that, over the long run, the economy will operate at the natural rate of unemployment, or the rate at which there is no cyclical unemployment.5 Expressed differently, the new classical position maintains there is no tradeoff between unemployment and inflation over the long run.

Natural Rate of Unemployment

The rate of unemployment at which there is no cyclical unemployment.

Aggregate Demand in the New Classical Model The aggregate demand curve in the new classical model is illustrated in Figure 9.4. Notice that it is basically the same as the aggregate demand curve in the classical model, with its emphasis on an inverse relationship between price levels and the amount of output demanded in the economy as a whole. With the new classical model, however, comes a more sophisticated explanation of the downward-sloping aggregate demand curve that has some important policy implications. The new classical economists provide three reasons for the downward-sloping curve: the interest rate effect, the wealth effect, and the foreign trade effect.

As overall prices change, the price of money, or the interest rate, also changes. When the interest rate increases along with an increase in overall prices, households and businesses borrow less and spend less, causing less output to be demanded. When the interest rate falls along with a decrease in the general level of prices, households and businesses borrow more and spend more, causing more output to be demanded. The downward slope of the aggregate demand curve is, therefore, shaped to a large extent by this relationship between the interest rate and spending, which is called the interest rate effect on aggregate demand.

Interest Rate Effect

The interest rate moves with changes in overall prices; there is an inverse relationship between the interest rate and the amount people borrow and spend.

People typically have some level of money wealth that they have accumulated and want to maintain. This includes, for example, cash, bonds, certificates of deposit, and such. When prices increase, the value of this accumulated wealth falls, and as prices decrease, the value of this accumulated wealth increases. In order to maintain the same value of money wealth, people will spend less when prices increase and more when prices fall. Again, the amount of output demanded increases with more spending and falls with less spending. The impact on the aggregate demand curve caused by changes in the value of money wealth is called the wealth effect.

Wealth Effect

In order to maintain the same amount of accumulated wealth, people spend less when prices rise and more when prices fall.

As prices rise in the economy, people may turn to lower-priced imports, and, as prices fall, people will likely buy fewer imports. This foreign trade effect provides another reason for the downward-sloping aggregate demand curve: As prices rise, spending on the domestic output of goods and services and, therefore, output falls because spending is diverted to imports; and, as prices fall, spending on domestically produced goods and services rises because spending is diverted from imports.

Foreign Trade Effect

There is a direct relationship between changes in overall prices in an economy and spending on imports that diverts spending from domestically produced output.

Aggregate Supply in the New Classical Model The aggregate supply curve in the new classical model can be viewed in two ways: short-run supply with three phases, or long-run supply. Figure 9.5a gives the short-run aggregate supply curve in this model. At low levels of output, the aggregate supply curve is perfectly horizontal. In this range, output levels are so low that prices are not affected as output changes. At some point, however, a direct relationship between prices and output occurs: Increases in output are accompanied by increases in the overall price level. Finally, at a high level of output, where the economy is producing at its capacity, the supply curve becomes perfectly vertical. Here the output level stays the same regardless of the level of prices.

The second view of the aggregate supply curve in the new classical model is the long-run view, illustrated in Figure 9.5b. Here the aggregate supply curve is similar to that of the classical school and is perfectly vertical at the natural rate of unemployment. In this long-run view, the economy moves toward the natural rate of unemployment and prices are flexible upward and downward.

Manipulating Aggregate Demand and Supply The level of prices and output toward which an economy moves depends on whether aggregate demand and supply are viewed in the short run or the long run. In Figure 9.5a, where the short-run view is taken, a shift of the aggregate demand curve to the left, from AD0 to AD1, brings about a decrease in output and prices. If AD1 shifted farther to the left to the flat portion of the supply curve, output would decrease but prices would not be affected. A shift to the right, from AD0 to AD2, brings about an increase in prices and output. If AD2 shifted farther to the right and intersected the vertical portion of the supply curve, price levels would rise but output would not be affected.

FIGURE 9.5 Aggregate Supply in the New Classical Model

Aggregate supply in the new classical model can be viewed in a short-run or a long-run time frame.

In Figure 9.5b, where the long-run view is taken, a shift of the aggregate demand curve in either direction brings a change in the price level but no change in output. In the long-run view, output is at the natural rate of unemployment and prices are flexible in either direction.

The Long Run and Policy Implications The policy implications of this long-run view are important because they suggest that the government should keep its hands off the economy. Any efforts to manipulate aggregate demand will, over the long run, result in no improvement in the level of unemployment but may cause the price level to rise. The ineffectiveness of government policies in reducing unemployment below its natural rate is called the natural rate hypothesis.

Natural Rate Hypothesis

Over the long run, unemployment will tend toward its natural rate, and policies to reduce unemployment below that level will be ineffective.

This long-run view of the new classical school is supported by the argument that households and businesses have expectations about how the economy should perform—especially with regard to inflation. The expectations may be adaptive expectations based on past and current experiences, or they may be rational expectations based on an understanding by households and businesses of how they would be affected by proposed government policies. Either way, because of these expectations, households and businesses act in ways that benefit themselves but undermine the intentions of policymakers.

Adaptive Expectations

Households and businesses base their expectations of the future on past and current experiences.

Rational Expectations

Households and businesses base their expectations of future policies on how they think they will be affected by those policies.

Suppose, for example, that the government follows policies to lower unemployment below its natural rate. In the process of moving toward this goal, more demand is added to the economy, causing the price level to increase. In other words, government policies to shift the aggregate demand curve to the right result in no change in unemployment but increase the price level. This effect, shown in Figure 9.5b by a shift in aggregate demand from AD0 to AD2, results because households and businesses respond to the expectation of rising prices and weakening purchasing power by negotiating higher wages and raising their prices.

Test Your Understanding, “Classical, Keynesian, and New Classical Models,” gives you an opportunity to strengthen your knowledge about these three important economic schools of thought.

New Keynesian Economics

Keynesians, unlike the classical and new classical economists, saw the economy as not automatically returning to full employment once unemployment occurred. Building on this foundation, and responding to challenges to the Keynesian view that developed after the 1960s, economists known as new Keynesians went about explaining why the economy could persistently operate at less than full employment.

What distinguishes new Keynesian economics from its rival schools of macroeconomic thought—especially classical and new classical economics—is how each views the behavior of prices. While classical and new classical economists regard prices and wages as flexible, new Keynesian economists regard them as inflexible, or “sticky,” downward. For this reason, new Keynesians do not think prices can be relied on to quickly drop and counter the adverse effects on employment that can result from a decrease in aggregate demand. Rather, because prices and wages are sticky downward, decreases in aggregate demand lead to adjustments on the supply side of the economy in the form of reductions in output and employment. Expressed differently, because prices do not drop, there is no mechanism to ensure that full employment will automatically be restored.

New Keynesian Economics

Builds on the Keynesian view that the economy does not automatically return to full employment; emphasizes downward sticky prices and individual decision making in the microeconomy.

Another distinguishing feature of new Keynesian economics is the attention it pays to decision making by individual firms, or decision making in the microeconomy. One important explanation for the downward inflexibility of prices and wages is that firms set their prices based on what is necessary to maximize their own profits, not on the basis of what is occurring in the economy at large. The fact that individual sellers can resist pressures to lower their prices and may find it most profitable to decrease output when aggregate demand weakens helps explain why unemployment can persist in the economy.

Monetarism

Another school of thought significant to macroeconomic theory is monetarism. Those who focus on the money supply and advocate altering it to stabilize the economy are called monetarists. Monetarism was a popular viewpoint in the 1970s and early 1980s and challenged Keynesian fiscal policy prescriptions. Monetarism's best-known proponent was Milton Friedman, whose association with the University of Chicago led some to label followers of his thinking as members of the “Chicago School.” Application 9.2 provides some background on Friedman.

Monetarism

School of thought that favors stabilizing the economy through controlling the money supply.

Monetarists

Persons who favor the economic policies of monetarism.

Monetarists are inclined to favor free markets and advocate limited government intervention in the macroeconomy. In this sense, they tend to align with the classical and new classical schools. Typically, a monetarist would suggest that allowing free markets and maintaining proper control over the money supply is the ideal strategy for reaching full employment or avoiding demand-pull inflation.

Supply-Side Economics

A discussion of alternative macroeconomic viewpoints would not be complete without some mention of supply-side economics, which was born in the late 1970s, popularized by its association with President Ronald Reagan and “Reaganomics,” briefly rejuvenated during the Dole–Clinton presidential race in 1996, and found support from some individuals in the George W. Bush administration. The basic idea behind supply-side economics is to stimulate the supply side of economic activity by creating government policies that provide incentives for individuals and businesses to increase their productive efforts.

Supply-Side Economics

Policies to achieve macroeconomic goals by stimulating the supply side of the market; popular in the 1980s.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

CLASSICAL, KEYNESIAN, AND NEW CLASSICAL MODELS

CLASSICAL, KEYNESIAN, AND NEW CLASSICAL MODELS

- Using the graph below, draw an aggregate demand curve and an aggregate supply curve that represent the classical model of an economy operating at full employment. Label these as D and S.

- Label the price and wage level at which the economy is operating as P0W0.

- Draw a second aggregate demand curve showing a decrease in demand. Label that curve D1.

- Identify the level of output and level of prices and wages that would result when the economy fully adjusted to the decrease in demand. Label the new price and wage level P1W1.

- Explain how the economy arrived at its new position.

- Fill in the table below, indicating where equilibrium output occurs as well as when the economy expands and when it contracts. On the accompanying graph, illustrate two lines. First, draw a “Spending equals Ouput” line and label it. Second, illustrate the relationship between “Total Spending” and “Total Output” in the table. All figures are in billions.

- In the graphs below, illustrate the new classical view of aggregate supply in the short run and in the long run.

- Illustrate a new classical demand curve in each of the graphs. Explain the changes in prices and output that would result from a decrease in this demand curve.

- Illustrate a new classical demand curve in each of the graphs. Explain the changes in prices and output that would result from a decrease in this demand curve.

UP FOR DEBATE

SHOULD GOVERNMENT'S ROLE IN INFLUENCING ECONOMIC ACTIVITY BE REDUCED?

SHOULD GOVERNMENT'S ROLE IN INFLUENCING ECONOMIC ACTIVITY BE REDUCED?

Issue One place where classical and new classical economics on the one hand, and Keynesian and new Keynesian economics on the other, part company is the desirability of an active role by government in keeping the economy as close as possible to a noninflationary, full employment level of output. Should the federal government play a less active role in stabilizing the macroeconomy?

Yes Government should play a less active role in stabilizing the economy. A major point of classical and new classical economics should be heeded: The economy, if left alone, will tend to operate at its full (or natural) employment output level. Overall price and employment levels are of greatest concern in the economy. If government views its primary responsibility as keeping markets as free as possible, the resulting movement of wages and prices should lead to the adjustments necessary to ensure natural or full employment levels.

A large, interventionist government, rather than solving macroeconomic problems, could add to them because it is reacting in an untimely way, or to the wrong signals, or on behalf of special interests rather than the overall interests of the economy.

No Government should not play a less active role in stabilizing the economy. According to Keynesian theory, there is no reason to expect an economy, left alone, to automatically reach a full employment level of output. According to Keynes, unemployment, or a recession, arises from a lack of total spending.

Unless total spending increases, or a spending “kick” occurs, the economy can remain stagnant. Since there is nothing inherent in the economy to ensure that this spending increase will occur, government is the logical choice to take the actions necessary to increase spending. It is efficient to give government the authority to lead the way. The wait for millions of decisions by individual households and businesses to spend more could be endless.

The best-known supply-side proposal is to lower taxes for businesses and individuals. It is argued that lowering the tax burden on businesses would make investments in buildings, equipment, and other productive resources more profitable, thereby stimulating growth in the economy. Lowering the tax burden on individuals is said to lead to greater savings (which could be channeled to businesses for investment purposes) and increased personal incentives to work. Government deregulation is also called for to increase productivity.

Supply-side proposals have a political as well as an economic dimension. Reducing taxes and regulatory requirements lessens the presence of government in private economic decision making. It also tends to have a more immediate impact on those with higher incomes.

The issue of how much government intervention in the macroeconomy is appropriate is a source of continuous debate. The position taken on this issue is often rooted in one of the theories just discussed. Up for Debate, “Should Government's Role in Influencing Economic Activity Be Reduced?,” presents some of the arguments for and against government intervention.

A FINAL WORD ON MACROECONOMIC VIEWPOINTS

By the end of this chapter, you have a good foundation for understanding macroeconomic theories and their relevance for solving macroeconomic problems. You have learned about past and present schools of economic thought that have made significant contributions to our understanding of the operation of the macroeconomy. Ideally, this chapter has provided the groundwork for informed judgments about past, present, and future efforts to understand and stabilize the economy.

It is helpful to keep in mind the discussion at the beginning of this chapter: An economic theory focuses on the relationship between two variables, and assumptions play an important role in the development of an economic theory. No theory is designed to explain all the complex relationships among the players and institutions in a macroeconomy. Furthermore, the economy is not composed of a set of simple relationships that can be easily manipulated to neatly solve various problems as they arise. One can be misled into thinking that a simple policy choice can cure all economic problems. In reality, there are many ramifications to choosing an economic theory as the basis for remedying an economic problem. Accordingly, the assumptions that underlie the theory should be known, as should the consequences that could result from implementing policy based on the theory.

Macroeconomic theories and policy instruments must be updated and refined as conditions change and knowledge grows. The environment in which models are built and policy tools are employed is continually changing, and new data, questions, and issues constantly appear. Also, the task of assessing economic theories would be easier if we lived in closed economies, where events beyond a country's borders have no effect on its output, employment, prices, or policies. The reality is that we live in open economies, which are influenced by actions in countries around the world. Political unrest in the Middle East, reaction to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), developments in China, and other circumstances outside the United States impact the U.S. economy and policies to stabilize it. As commercial relationships become more global and the economy becomes more open, the need to refine and update our knowledge becomes even greater. It is risky to assume that an understanding of the way things operate today will be sufficient to deal with the problems of the future.

Closed Economy

An economy where foreign influences have no effect on output, employment, and prices.

Open Economy

An economy where foreign influences have an effect on output, employment, and prices.

APPLICATION 9.3

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO …

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO …

A major economy in today's global playing field is so complex that it can be mind-boggling to try to sort out the factors and relationships that provide for an economy's healthy growth and good jobs and incomes or spin it into a downward spiral. Trying to understand how the pieces of this gigantic and important puzzle called an economy fit together is the lifetime work of many macroeconomists as they explore and build theoretical relationships. Some of their research seems to be on target and has staying power in the profession's catalog of important contributions.

It is often the emergence of a major problem or issue, such as the Great Depression or prolonged high rates of inflation, that is the impetus for macroeconomic problem solving. And, sometimes the discovery of and data proof of a cause-and-effect relationship holds up in the short-term but becomes debatable with time. The Phillips curve is one example.

In 1958, William Phillips popularized the idea that there was an inverse relationship between rates of inflation and rates of unemployment: low unemployment was associated with high inflation and vice-versa. Over the years, this simplistic idea has shown to be true in some short-term data aggregations. But there have been many rebuttals by well-known economists who have created variations on the Phillips curve from their research, and have framed both short-term and long-term alternative Phillips curves. Other economists are reviving the basic tenet of the relationship and incorporating it into new models.

What economists know in their theorizing is that short-term and long-term viewpoints and relationships can be different. What might be true over the period of a few years might not hold true if you take a long view. This further complicates the understanding of puzzle pieces and how to recommend policy proposals that might be needed to address short-term problems.

Finally, let us not forget that economists are just like the rest of us even though many folks believe that economists are wired a little differently. We are all driven by our values and those values play a role in what we regard as the ideal world. Beliefs about the importance of free markets versus government intervention, the rights of the individual versus the rights of society, and other beliefs influence how and what we think. We see those different thought processes in research, textbooks, and classroom presentations. During a stint as department chair, one of the co-authors of this text had to deal with a part-time faculty member who eliminated all material in his basic macroeconomics course but monetarism. When questioned about the narrow view given to his students, the response was simply “I don't believe that any other theories are valid.”

Application 9.3, “The World According to …,” offers some additional thoughts about macroeconomic models and macroeconomists.

Summary

- Economic theory focuses on the relationship between two variables. Economic theories are explored within the context of a model that includes variables, assumptions, data collection and analysis, and conclusions. Because economic theories are often an attempt to identify the cause of an economic problem, macroeconomic theories frequently have an historical dimension.

- There are several schools of thought important to the development and understanding of macroeconomics. These include classical, Keynesian, new classical, new Keynesian, and monetarism.

- Classical economics was the prevailing school of thought prior to the 1930s and the Great Depression. The classical aggregate demand–aggregate supply model focuses on the relationship between price and wage levels and output levels. This model concludes that a free market economy's output level always self-corrects to full employment and that prices and wages increase and decrease with changes in aggregate demand. Increases in aggregate demand bring increases in prices and wages, and decreases in aggregate demand bring decreases in prices and wages.

- Keynesian economics gained prominence during the 1930s when John Maynard Keynes introduced the ideas that a macroeconomy can move toward an equilibrium output level that is less than full employment and that no mechanism is built into the economy to automatically move it toward full employment. Keynes focused on the role of total spending in the economy, indicating that the equilibrium output level of an economy is a direct result of the level of total spending in the economy.

- Macroequilibrium occurs in the Keynesian model when total spending equals total current output, or when the leakages from and injections into the spending stream are equal. When spending is greater than the current level of output, which is caused by injections exceeding leakages, the economy expands. When spending is less than the current level of output, which is caused by leakages exceeding injections, the economy contracts. Keynes advocated government intervention, or fiscal policy, to move the economy from equilibrium at low levels of output to equilibrium at a higher full employment level of output.

- New classical economics was born in the 1970s when many of the world's economies experienced stagflation and Keynesian economics could not offer an explanation for the serious inflation. New classical economics focuses on an aggregate demand–aggregate supply model similar to the classical model. Aggregate demand is represented by a downward-sloping curve showing an inverse relationship between price and output demanded levels based on interest rate, wealth, and foreign trade effects.

- New classical aggregate supply can be viewed in the short run or long run. In the short run, prices do not change at low levels of output, a direct relationship exists between prices and output in the intermediate range, and at high levels of output prices are flexible upward and downward and output does not change. The long-run view of aggregate supply is based on the natural rate hypothesis: The economy moves toward the natural rate of unemployment as price changes bring aggregate demand into equality with aggregate supply. The new classical school advocates little government intervention in the economy because adaptive and rational expectations by households and businesses undermine the intentions of policymakers.

- New Keynesian economics builds on the Keynesian view, emphasizes the inflexibility of prices and wages downward, and attempts to better connect macroeconomics to microeconomic decision making. New Keynesians also stress that the macroeconomy does not automatically adjust to full employment.

- The monetarist school of thought focuses on the role of money in the economy and advocates changing the money supply to stabilize the macroeconomy. Supply-side economics focuses on policies to increase production and productivity.

- In evaluating macroeconomic theories and policies, we must continually update our thinking to meet changing conditions. The economy is not composed of simple relationships that allow for neat solutions to economic problems. It must be remembered that individual economic theories focus on specific variables, and that all theories are built on underlying assumptions.

Key Terms and Concepts

Classical economics

Keynesian economics

Macroeconomic equilibrium

Inventories

Stagflation

New classical economics

Natural rate of unemployment

Interest rate effect

Wealth effect

Foreign trade effect

Natural rate hypothesis

Adaptive expectations

New Keynesian economics

Monetarism

Monetarists

Supply-side economics

Closed economy

Open economy

Review Questions

- Identify the four basic components used to develop a model and explain how macroeconomic models can be influenced by history.

- Show how the classical economists thought about aggregate supply by graphing the classical aggregate supply curve. Explain why they believed that this represented the economy.

- Draw an aggregate demand curve for the classical school on the graph in number 2 above. Explain what happens in the economy when this demand increases.

- Fill in the column below (where all figures are in billions) by indicating whether the economy is expanding, contracting, or at equilibrium. On the graph following, draw a “Spending equals Output” line and a line showing “Total Spending.” Explain the relationship between these lines at output levels of $600 and $1,800 billion.

- Using the information from number 4 above, explain how the relationship between Leakages and Injections influences the economic conditions in the last column.

- Explain how the interest rate, wealth, and foreign trade effects are important to aggregate demand in the new classical model.

- What is the difference between short-run and long-run aggregate supply in the new classical model? What implications does each view have for understanding the economy?

- Fill in the following table by providing, for each listed school of thought, the variables on which the theory is built, the conclusions with regard to the macroeconomy, and the role of government intervention advocated.

Discussion Questions

- “When the economy is facing high rates of unemployment and inflation, policymakers must decide which of these problems to curb at the expense of the other.” Is this statement accurate? What types of information should policymakers seek before deciding to sacrifice employment for price stability or price stability for employment?

- Would you consider yourself to be classical, new classical, Keynesian, new Keynesian, monetarist, or other in your attitude toward macroeconomic policies? On what reasoning is your preference based?

- What is the natural rate hypothesis and what problems does it cause for those wishing to pursue aggressive macroeconomic policies? What problems might adaptive and rational expectations cause for the government in its macroeconomic policymaking?

- Macroeconomic policy proposals are frequently tied to political agendas. In your opinion, which of the policies that you have studied is politically the most desirable, and which is the least desirable? Explain.

- Just as macroeconomic problems affect economic theory, they also affect the arts—visual art, music, and literature—of the day. Give an example of how a piece of visual art, a song, a novel, or a poem reflects the state of the macroeconomy at the time it was created.

- How do the assumptions underlying the various theories you have studied in this chapter help to explain why debates on the proper role of government in macroeconomic activity can become so heated?

- One lesson from this chapter is that the popularity of an economic theory depends in part on its ability to offer solutions for current, pressing problems. Because economic theories move in and out of fashion as conditions change, does this mean that they are not scientific after all?

Critical Thinking Case 9

DOES ANYONE CARE WHAT ECONOMISTS THINK?

Critical Thinking Skills

Identifying real-world implications from seemingly unreal-world concepts

Recognizing and evaluating values underlying technical arguments

Economic Concepts

Full employment—automatic or not

Government's role in managing the economy

We've just gone through several macroeconomic theories. In exploring these theories you have put up with graphs, theory-makers' assumptions, technical terms such as natural rate of unemployment, and radically differing views on how the world works. These theories are abstract and often contradictory. So much so that George Bernard Shaw said that if you laid all economists end to end you'd never arrive at a conclusion, and John Maynard Keynes hoped for the day when economists would be thought of as humble, competent people—like dentists.a Given all this, it is entirely reasonable to ask: “Why would policymakers or others in important decision-making positions pay any attention to what economists say?”

a John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (New York: W.W. Norton, 1963), p. 373.

Questions

- Do you think policymakers pay attention to ideas like those we have seen in this chapter? Why?

- Each of the theories in this chapter directly or indirectly takes a position on what public officials should or should not be doing about the macroeconomy. Which of these theories would be supported by an administration wishing to actively manage the economy? Which would be opposed? Why?

- Is it possible to develop a value-free economic theory? Is it possible to follow a policy that is compatible with all of the theories in this chapter?

- Do you think policymakers are more likely to stick with long-accepted theories that they know or more likely to readily adopt new theories that address the problem at hand? Why?

1 Songs of the Great Depression, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?,” lyrics by Yip Harburg, music by Jay Gorney (1931), http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/history/lavender/cherries.html.

2 “Say's Law,” named after the French economist Jean Baptiste Say (1767–1832), states that supply creates its own demand. According to James Mill (1773–1836), one of the important popularizers of this position, whatever individuals produce over and above their own needs is done to exchange for goods and services produced by others. People produce in order to acquire the things that they desire, so what they supply and what they demand are equal. And if each person's supply and demand are equal, it follows that the supply and demand in the entire economy must be equal. Believing that demand and supply are equal for the entire economy, the classical economists saw surpluses in specific markets that would lead to unemployment as being offset by shortages in other markets. The surpluses would be removed by businesses following their own self-interest and guided by the profit motive. See James Mill, Elements of Political Economy (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1826), Chapter IV, Section III, especially pp. 228, 232, 234–235.

3 John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1936).

4 Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008), pp. 276, 300.

5 Be sure not to confuse the natural rate of unemployment with the full employment rate of unemployment, which includes only the frictionally unemployed. Review Chapter 4 for further information on these concepts.