The Dark Side

This chapter discusses how social media is used by cybercriminals as the latest tool to commit various illegal, unwanted, and/or malicious acts. Those using social networks can fall victim to a wide variety of acts, inclusive to scams, social engineering, cyberstalking, cyberbullying, online predators, hacking, or other acts related to Internet security. We’ll discuss a variety of ways to protect yourself, methods to identify and deal with potential problems, and issues you can avoid.

Keywords

Social networking; social media; communications; privacy; security; cybercrime; cyberstalking; cyberbullying; predators; social engineering; phishing; hackers

Information in This Chapter:

The dark side of social media

Every community has areas that are on the wrong side of the tracks. The virtual world can be a wonderful place, allowing you to interact with networks of people, enjoy the isolation of a game, or chat with groups or one-on-one, but not everyone or everyplace is safe. The Internet can be deceptive and make you overconfident and unwary of predators, charlatans, and scams.

As we’ve seen throughout this book, there are many threats on the Internet, but a person is especially vulnerable when using social media. Social platforms rely on sharing information, engaging others, and having trust. Social media is about friends, followers, connections, and sharing. These words instill trust, giving us faith in the links we click, the programs we install, requests that are made, and questions asked. Unfortunately, trust is also necessary to take advantage of someone.

Cybercrime

Cybercrime is a criminal activity that involves computers and the Internet. A cybercriminal may use online resources to obtain information about a person, as a medium to contact potential victims, gain access to systems, and/or damage data and bring down systems. The types of offenses will vary, but they will always involve technology and connectivity.

The targets of cybercrime may be computers or people. A cybercriminal may focus an attack on systems using viruses or other malicious code, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 8, or by directly hacking a system to gain unauthorized access. They may also focus their attention on people to steal their identity, commit fraud, stalk, or bully them. It may also be a precursor for other offenses, where the crime is initiated online, but later violates or injures the person through later physical contact.

Scams

Online scams aren’t new to the Internet but have evolved and taken new twists on social networking sites. Cybercriminals can gain in-depth information from your profiles and may make connections through friend requests. This has made many of the scams sent through email more personal and believable.

Grandparent scams have been typically done over the telephone and involves an elderly person being called by someone claiming to be a relative or grandchild. The person may claim that they’ve been in a car accident or in some other trouble and needs money wired to them. With social media, the scammer may make a friend request to the victim first, establishing a relationship as a long-lost relative before trying to get money through online chats, instant messages, or over the phone.

Shared stories are a common way for scammers to gain money. A link may be shared to a controversial video, interesting app, or something else that will entice people to click it. This may be an offer for a discount at a popular store or some fake feature offered by the site (such as a dislike button on Facebook). When the link is clicked, people are taken to online surveys or other sites that pay the scammer referrer fees.

You’ll also see bogus job offers on Twitter or through direct messages on other sites like LinkedIn. They’ll say you can make large amounts of money by working from home and may require you to pay a start-up fee. In other scams, a bogus perspective employer will try and get sensitive information from you, such as your Social Security Number or other information that should only be given after you’re hired by the company. You should always be careful about work-at-home offers, jobs that require no previous experience, or online requests for sensitive information. The offers seem too good to be true, because they generally are.

According to the 2012 Internet Crime Report, created in partnerships between the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the National White Collar Crime Center, one of the most frequently reported Internet crimes is the Hit Man Scam. There have been variations over the years, but the basic premise involves an email being sent to you by someone pretending to be a hit man, who’s been hired to kill you or someone you care about. If you pay a certain amount, then the kind killer won’t fulfill the contract. To convince you that the threat is legitimate, scammers have begun to use social media to get personal information about you or facts that can make it seem more convincing. After all, if they have your name, address, phone number, and other tidbits of data, it would certainly scare you into believing the person knew how to get at you.

Scams are designed to get something from you and are usually financially motivated. To protect yourself, you need to be wary of strangers, the offers they make, and the sites you visit. To ensure your accounts haven’t been compromised, you should monitor your statements and look for any strange charges. If you find any transactions you didn’t make, contact the credit card company or bank to inform them the account may have been compromised.

Using secure browsing

Secure browsing is an important feature on any site containing personal information or where you make online transactions. It’s important that any communication between your computer and the sites used for banking or online purchases is secure. Browsers should use Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) to safely exchange data with a site, as this provides encrypted communication and secure identification of a network’s Web servers.

You can tell whether HTTPS is used by looking at the address bar in your browser. The Uniform Resource Locator (URL) should begin with https://. Your browser may also display a padlock icon to show if the site is secure. Newer versions of Internet Explorer display a padlock icon on the right side of the address bar, while Firefox provides a Site Identity button to the left of the address bar. Clicking on these will display information about the site, inclusive to whether the site is verified, who owns it, and if communication is encrypted. By ensuring the site is correct and communication is secure, there’s less chance of a scammer getting your information and stealing your money or identity.

Of course, just because you’re using a secure connection doesn’t mean your protection is absolute. If a site has been compromised, then the connection may be secure, but the end point of that connection won’t be. When the site is hacked, your credentials can be taken regardless of how you’re connecting to a site. An issue occurred in February 2013 when the customer support vendor Zendesk was hacked, allowing the hackers to download the email addresses of people who contacted Twitter, Pinterest, and Tumblr for support. While passwords weren’t obtained in this attack, it doesn’t mean they can’t be acquired through a follow-up phishing attack, as we discuss later in the chapter, or other security breaches.

Issues can also arise when the apps you use to connect to sites have security vulnerabilities that are exploited. In July 2013, Tumblr (www.tumblr.com) had a security issue with their iOS app, which allowed passwords to be detected. The site released a security update for iPhone and iPad users and recommended that users to change their passwords.

Many social media sites provide features for secure browsing but generally need to be activated. As we saw in Chapter 3, LinkedIn provides a setting you need to activate, while on Twitter HTTPS is used by default. On Facebook, you can turn on secure browsing through the Security Settings page of your account. To activate the feature, do the following:

1. Click on the Settings menu, which is the gear-shaped icon in the upper right-hand corner of the page. When the menu appears, click Account Settings.

2. In the left pane of the page, click Security.

3. In the Secure Browsing section, ensure the Browse Facebook on a secure connection (https) when possible checkbox is checked.

Cyberstalking

Cyberstalking is a form of repeated harassment that involves the Internet and methods of electronic communication like email, online chat, and instant messages. Just as an offline stalker will follow or stakeout a victim, an online stalker will use electronic and Internet-based tools to track the object of their obsession. Victims of cyberstalking may be threatened, receive viruses or malware in email, and have false accusations or statements posted online to encourage others to join in the harassing of the person. For obvious reasons, cyberstalking can be terrifying for the victim.

Unfortunately, social media is an excellent tool for cyberstalkers to track and monitor a person. Social networking sites can provide information on where a person works, their location, who they associate with, likes and dislikes. Using this, you may be able to identify where a person is at a given time and meet them face-to-face or engage them online.

When reported in the news, stories of cyberstalking are often strangers stalking celebrities. An example of this occurred in 2011, when actress Patricia Arquette quit Facebook after an alleged incident where she was harassed. Her final post warned people about adding strangers as friends. However, cyberstalkers aren’t necessarily strangers, and the victims aren’t just celebrities.

In 2010, Lee David Clayworth dated a woman named Lee Ching Yan for several months while teaching in Malaysia. After they broke up, she stole his laptop, hacked his email account, and began harassing him. Contacting people in his account’s contact list, she posed as Clayworth and sent messages about how he’d had sex with underage students. The laptop she stole contained nude photos she’d taken of him, which she posted on various sites. The cyberstalking progressed with her posting hundreds of comments and false accusations, to the point that a Google search of his name showed links to how he was involved in deranged or criminal behavior.

Although harassment is illegal, it doesn’t mean it’s always enforceable. Clayworth sued Yan in Malaysia, and the court awarded him the equivalent of $66,000 in damages. She continued with the defamation, so the court found her guilty of contempt of court. She moved out of the country and continued her harassment.

Attempting to remove the content from sites was difficult for Clayworth. While some sites have been helpful, Yan has reposted the false information after it’s taken down. Other sites like liarsandcheaters.com have opposed his actions to have content removed. The manager of the site wrote that he would relocate the site to Germany, so Clayworth would have to go through German courts to have it removed. The manager stated that until then “the post will remain permanently for the rest of your life.”

While it can be difficult or impossible to find a legal resolution if the cyberstalker resides in another country, you should still make an effort to report the abuse to sites and police. The person harassing you may be lying about their location and reside in the same country or same city as you. It’s better to take action and view the situation as a genuine threat.

Protecting yourself

As with real-life stalkers, a cyberstalker’s motivation is to control the victim, and this is done through intimidation. In cyberspace, the stalker may feel even bolder, hidden behind aliases, and believing in the anonymity of the Internet. Being the victim can feel paralyzing, but there are ways to take control and protect yourself. To combat cyberstalking, you need to limit the information you post online, remove their ability to access information, and prevent them from contacting you.

Many victims have been involved in some kind of relationship with the cyberstalker. They might be a former girlfriend or boyfriend, an estranged or ex-husband/wife, or someone else you’ve had an intimate relationship with. They might even be a former friend or roommate. Because they had a relationship with you in the real world, they had access to your computer, mobile device, wireless router, and other equipment.

As we’ll see in Chapter 10, keyloggers or other monitoring tools can be installed to record the characters you type and take screenshots of what you’re doing on your computer. As you enter passwords or visit sites, the information is captured and can be emailed to a person or uploaded to a site. If the cyberstalker had access to your machine, he or she could have easily installed such software. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 8, anti-malware/antivirus tools can be used to detect and remove such malicious software.

Your first reaction to reading any messages received by a cyberstalker is probably to delete it. However, unless it’s a file that’s been quarantined or deleted by antivirus software, you shouldn’t delete anything from a cybercriminal. The messages can be important evidence, and a forensic investigation may reveal important information on who sent the email and where it originated. If you’ve received a direct message on a site, simply don’t delete it. If you’ve received it in the inbox of your email account, you can move the offending message into its own folder. When you do contact police to file a complaint, you may be asked to forward it to the officer.

Because the person may have had access to your passwords before, you should change your passwords. This includes the ones for social media sites you use, email, your Internet Service Provider (ISP) password, and banking sites. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 10, strong passwords should be used, and these should be changed regularly. If you have a home security system, you should also change the access codes and any verbal passwords used when talking to the security company. It does little good changing the codes, if the person can talk to the security company, tell them a password, and have them disable the alarm.

If you have a wireless network in your home, you should also change the passwords on the router. Wireless routers have an IP address that displays an administration site that’s used when you set it up. You should go onto this page and change the administrator password, any password used to join the network, and remove any devices your stalker has previously set up to connect to the network. If the person had previous access, the person could change these passwords and lock you out of your own network. He or she could also use a network protocol analyzer like Wireshark (www.wireshark.org), which will capture the packets of data sent across the network. Using such a tool, the person would be able to see any passwords sent in clear text or any sensitive data. To ensure the data you send and receive is secure, you should make sure that encryption on your wireless router is turned on through the administration page.

Regardless of whether you know the stalker personally or not, you should send a single response telling the person to stop harassing you. Tell the person to leave you alone and that you will contact authorities. If they want to talk about it, never agree to meet face-to-face and don’t involve yourself in any further discussions.

In addition to the steps we’ve already discussed, you should use methods discussed throughout this book to secure your social media, including:

• Use features to block the person’s access to you. In Chapter 9, we’ll see that by blocking the person from visiting a page or blog, you’ll restrict them from making comments and viewing your information.

• Know what’s being said about you and where. As we’ll see in Chapter 10, there are ways to perform online searches of people. It is wise to do a search of your own name and family members and remove any personal or revealing information from these sites.

• Report Abuse. As we saw in Chapter 6, abusive behavior is a violation of the Terms of Service for many sites and ISPs.

• Be wary of revealing your location. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 9, be careful of apps or making posts that show where you are or where you’ll be.

It is always advisable to contact authorities and consider legal action if threats are made or you’re fearful of your safety. If you’re concerned the person will contact you in real life, restraining orders may be used to restrict the person from coming within a specified distance of you and may also have conditions from contacting you in other ways.

Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying is another form of online harassment, where a person or group bullies a victim using the Internet and/or other methods of electronic communications. If this sounds like cyberstalking, you’re not wrong in making the comparison. Both involve many of the same methods to terrorize a victim. The cyberbully may post abusive comments, send threatening or demeaning messages, make audio or video records of someone without their consent, or disclose personal information with the purpose of humiliating or intimidating them. As with any bully, they like the power that comes through humiliating and demeaning another person.

An extreme example of cyberbullying occurred in 2006, when a 13-year-old girl named Megan Meier started an online friendship through MySpace with a 16-year-old male named “Josh Evans.” Messages to the girl started out complimentary but eventually turned vicious. Emails to her said he didn’t want to be friends as she wasn’t nice to her friends, and messages posted on the page stated “Megan Meier is a slut. Megan Meier is fat.” Devastated by the betrayal of friendship and public humiliation, the 13-year-old girl hung herself.

What was discovered later was that Josh Evans never existed. The account had been created by an adult named Lori Drew, who was the mother of Sarah, a former friend of Megan. The mother had created and monitored the profile and had been aided by her daughter Sarah and an 18-year-old employee named Ashley Grills. Although they had bullied Megan to the point of committing suicide, Lori Drew was indicted and convicted of a misdemeanor for violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act for breaching the MySpace Terms of Service. In 2009, the conviction was overturned by Judge Wu of the Central District of California.

Since that time, there have been many laws passed directly dealing with cyberbullying and online harassment. California state legislature passed Assembly Bill 86 2008, which allows schools to suspend or expel students for bullying online or offline. Many school codes have also been amended to include provisions that deal with bullying, and it’s common for schools to implement anti-bullying programs that address this problem.

While cyberbullying often refers to behavior where a child or an adolescent is bullying another minor, adults can also be bullied online. As with children, if an adult is bullied, it’s important to speak up and tell others. For those experiencing workplace bullying, you should explain the issues to management and/or a union representative. Many organizations have policies that address harassment and would (or should) take such complaints seriously for fear of being vulnerable to a potential lawsuit.

For children or teenagers, it’s important to tell an adult. If the adult doesn’t take the problem seriously, then tell another adult who will. According to the 2011 report by Pew Internet and American Life Project, when teens sought advice about a problem like mean behavior on the Internet, 53% turned to friends and 36% confided in their parents. Almost all said the advice they received was helpful.

It’s also important to tell the bully to stop. The person may see the unwanted behavior as a joke or posting what they said as acceptable. In telling them it’s not acceptable, they can’t say they didn’t know and excuse it as a prank. Sending a single message telling them to stop can serve as evidence against the person when you contact police, employers, or school officials.

Sometimes, a cyberbully is a former friend or pretended to be one. As we discussed with cyberstalkers, if the bully had access to your computer, you should change passwords. The same applies if you used their computer. If your password was logged or the site was set to remember you on your next visit, the bully could log on to the site as you. To protect yourself from any monitoring tools or devices, you should check your computer for any USB sticks or devices that may have been plugged in and run a scan for any malicious software that may have been installed. In addition to this, follow the steps we discussed in the previous section to protect yourself.

Cybersex and other intimate issues

Social media is used to make connections, but many use it to engage others more intimately. Many people use chat rooms, dating sites, and social networks to make romantic or sexual connections. Others use these same forums to make a connection with potential victims. The person may be looking to initiate a virtual relationship that leads to stalking or sexual assault, as a precursor to blackmail, or any number of online scams.

Romance scams

A common scam involves the promise of love and companionship. A cybercriminal will use chat rooms or sites to find and romance a victim. According to the 2012 Internet Crime Report, with the exception of men who are aged 20–29, women in every age demographic are more frequently victimized by this scam. Gathering information on your profile page, a person might see what books, music, movies, and other pastimes you like and claim a shared interest. Using this, posts on your wall or tweets you’ve made, they can determine your likes and dislikes. The scammer may post flattering comments, entice you with promises, and gain your interest with fake pictures that are supposed to be of them. Once you trust the person, the scammer will ask for favors. You may be asked for money, requested to help by receiving and reshipping a package, or do something else on their behalf. The scam generated 4467 complaints to the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), with victims collectively losing more than $55 million.

Romance scams work because they play on your emotions. The person will often say how you were meant to be together and claim to love you or have feelings within 24–48 hours of first meeting online. They may ask you for your address to send you a gift, and in some cases, you might actually receive something, such as flowers or some other token of affection bought with a stolen credit card. In time, they may even ask for some money so they can visit you or ask another favor that will cost you.

Chat rooms

There are many ways in which people will interact online. There are discussion boards and chat room sites like Dephi Forums (www.delphiforums.com), where people can create accounts and join in public chats with groups of people or private chat rooms of two or more people. Virtual gaming worlds and social worlds provide the ability to engage in conversations with other players, and even games on Facebook may provide features where you can type back and forth to other users. Once two people get along, they may decide to break away from the site and use Instant Messaging (IM) or chat clients, which are designed for exchanging messages and may have features like audio/video chat, the ability to exchange files, or clickable links so that people can visit sites or see the same content.

Because you can share links and files through chat sites and client software, you need to be careful of what you click and receive. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 8, a file you receive could be malicious software or contain a virus, and sites offering pornography are notorious for having malicious code that may install viruses or other software on your machine.

The software used to chat should also be a concern. In 2011, Facebook partnered with Skype to introduce a video call feature, which scammers took advantage of. Clicking on a link to “Enable Video Calls” that was shared on Facebook, you were asked to install an app, which requested permission to access your data and information (even when it wasn’t being used), and post on your wall and newsfeed. After allowing this, SPAM would be sent to your friends with links to surveys. The scammers profited from referral fees, as people were sent to the sites.

Blocking chat in Facebook

Facebook provides a chat feature that shows people who are available to chat in the right-hand side of your page and newsfeed. By clicking someone on the list, a small chat pane will appear where you can type your messages back and forth. If a person is unavailable for chat, any messages you send will appear in their inbox, where they can be read later.

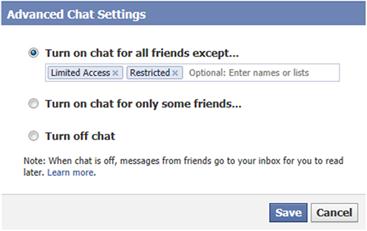

Facebook provides a number of settings to control who can chat with you. In the lower right-hand corner, at the bottom of the sidebar, you’ll see a gear-shaped icon for controlling your chat settings (Figure 7.1). On the menu, you could click Turn Off Chat so the chat feature is no longer active during your current session, but chat will turn back and be available when you next log on. For greater control over the chat feature on Facebook, you would click Advanced Options to get a dialog box of options.

The first option on the Advance Chat Settings dialog box is Turn on chat for all friends except, where you can specify individuals or lists of people you’d rather not chat with. In selecting this option, you would enter the names of any lists or people who can’t chat with you. As we’ll see in Chapter 9, you can use existing lists or create your own custom lists of people. Anyone not mentioned will still be able to chat with you.

Another option is Turn on chat for only some friends, which allows you to specify that certain people will be able to chat with you. When you select the option, a box appears where you can add those elite individuals and lists of people who will have the ability to engage you in chat. Everyone else won’t be able to chat with you.

The final option is Turn off chat. Unlike the option on the settings menu that we mentioned earlier, this setting will turn off chat and keep it off. When you next log on, it will still be turned off and remain off until you change this setting. Turning off chat doesn’t completely isolate yourself from others, as people will still be able to send messages to your inbox.

Cybersex

Online conversations aren’t always G-rated. Cybersex is a term that describes a sexually explicit conversation that simulates a sexual encounter. Those chatting with each other often don’t know each other in real life. Their conversations may involve flirting, or extend into a sexual dialog of what they like or sharing fantasies, and may be used as stimuli for masturbation. Assuming it involves consenting adults, there’s nothing illegal about it.

While you might think such activities are rare, you’d be wrong. According to a 2004 study, out of 1828 people surveyed, 658 women and 800 men claimed to use the Internet for online sexual activities, and almost one-third of the men and women reported they’d engaged in cybersex. While popular, it isn’t without its share of risks.

Chat sites often use aliases, where you create an account with a username to prevent others from seeing your real name. The anonymity is a powerful and attractive feature, but it’s important to realize that it goes both ways. You don’t really know who you’re chatting with. The person who asks you to engage in cybersex or cyber may claim to be in their 20s or 30s, but it could also be someone who’s 13 or 63. If the person is underage, you may wind up having to address the additional legal issues of having inadvertently corrupted a minor, Internet luring, or (if photos or video were exchanged) being charged with receiving child pornography. Everything about the person, even their gender could be a lie. Alternatively, it could also be a coworker or someone you know, causing great embarrassment. Just as the alias isn’t your real name, the personal information and photo on a profile page could also be fake.

Anonymity can be empowering. It can make you feel like you can say anything, as if you’re protected behind a secret identity. A person can reveal what excites them and talk in a way they never would to even a real-life partner. It also provides a mechanism for sharing personal details, intimate secrets, and discuss personal problems with work and relationships. The information you give could be used by a cyberbully or cyberstalker to gather information about you or (as we’ll see later in this chapter) as a social engineering ploy. As with other online sexual activity, cybersex often isn’t discussed or admitted to in real life. Because it’s a secret, a spouse or boyfriend/girlfriend discovering these virtual relationships may see it as a betrayal or an infidelity. If a real-life partner sees it as cheating, it can destroy the relationship, causing embarrassment or even legal action, as in the form of divorce or child custody proceedings. Prior to engaging in cybersex, you should understand how your real-life partner feels about online sexual activities and respect their opinion.

Virtual relationships can go beyond cursory ones. If two people meeting online like each other, they may add one another as friends, creating an online relationship. The ongoing exchange can also invoke real feelings, evolving it into an online affair or even a real-life one. Unlike real-life relationships, you experience the person in fragments, only seeing the aspects they want to reveal which may be completely fabricated, and filling the rest in with fantasy.

The best way to approach a chat room is the way you would a bar. You’ll meet people seeking friendly conversation, those who are lonely and want companionship, and others seeking sex. While many people are nice, there are also those who will try and get what they can from you. Once they have you in private, some may use mind games or trickery.

Whether it’s to scam or play you, a person who’s trying to get something will often use sweet talk. Almost everything they say is positive, encouraging, and something you want to hear. While peppering you with compliments, they may also make subtle jabs against any current relationships you have. They may say If I were your boyfriend/girlfriend, I would … followed by a positive comment. The wording places a suggestion to think of that person in a relationship role and insinuates they’d make a better partner than your real-life one. If he or she can undermine current relationships, it may keep you from turning to others and talking about the chats. The person wants gain your trust, so they can get what they want.

The person may ask for your phone number to call and talk in person, ask you to call him/her, or suggest a video chat. While the person may genuinely want to connect with you, the request could also be part of a blackmail scheme or some other scam. A phone conversation may turn sexual and recorded, while a person using a webcam may be lured into remove clothing or even perform sexual acts. The blackmailer will take screenshots or capture the video and then demand payment or some other favors in exchange for not posting the images or video to the Internet.

Before any chats or online dating goes too far, you should do a little detective work. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 10, online tools can be used to find detailed information about a person. Even a simple check can be revealing. By typing a phone number, email address, account name, or other information provided by the person, you can establish whether the details they provide appear true. Because many scams involve sending packages or money to another country, if they claim to be local and say they’re out of the country, be suspicious.

When it comes to video chatting, you need to be careful. If you’re chatting with someone you haven’t met in real life, you should try and determine if it’s a live feed. Scammers may hide their identity by using prerecorded video of someone else. Maybe they’re fooling you into thinking they’re more attractive, hiding their age, or don’t want you identifying them to police. If you’re typing messages back and forth and not talking with one another, you wouldn’t be able to match the audio with movements of the person’s mouth. To ensure it’s a real person, get them to do something like point at a corner of the screen or hold something up to the camera. If they refuse, it may be because they can’t.

Sexting

Sexting is a variation of cybersex in which sexually explicit text messages are exchanged and may include suggestive, nude, or pornographic images or video. The text messages, images, and video are often shared using mobile phones. Unlike cybersex, where the partakers of the activity can be a real-life couple but more often involves people who don’t know each other offline; sexting more commonly involves participants who know one another and have exchanged phone numbers.

While the majority of people with mobile devices haven’t sent or received a sext, there are many who have. According to a 2012 study by Pew Internet & American Life Project, 15% of adult cell phone owners have received a nude or nearly nude photo or video from someone that they knew, and 6% have sent one of themselves to another person. Being that it’s common for mobile phones and tablets to have a built-in camera, it’s easy for someone to take advantage of the technology and include a picture or short video without thinking of the repercussions.

Sexting isn’t limited to any particular age group. The majority of those receiving, sending, and forwarding sexts are younger, between the ages of 24–34, with the second largest group being 18–24. However, people of all ages have done it, including teenagers. In a 2009 study, Pew surveyed cell phone owners between the ages of 12–17 and found similar behavior, inclusive to sending and receiving sexually suggestive or explicit images. 15% of the teenagers had received a sext on their mobile phone, while 4% had sent one of themselves.

Sending such photos or videos to someone doesn’t mean that it will stay with that person. You may have sent a suggestive photo or video to a boyfriend, girlfriend, or spouse, but it can easily be forwarded to other people. The 2012 study by Pew found that 3% of adult cell phone owners forwarded a sexually suggestive or explicit photo or video of someone they know to another person. Once it’s shared, it could be sent to coworkers, family, or even uploaded to a porn site and be passed around for years.

Fake photos and video

Some people want to hide their identity online. It may be for protection, as in the case of someone visiting a chat room and wanting anonymity or it may be a scammer who relies on concealing his or her true identity. As part of a false persona, the person may use fake photos on profile pages. Often these are from other people’s sites or from stock photo sites. For example, by going to Shutterstock (www.shutterstock.com), you can search millions of stock photos and find a photo of a model that suits your needs. Fortunately, while it used to be difficult identifying if a person’s photo was fake, Google has made it easier.

Google provides a feature to find identical or similar photos of a person. By uploading a photo or using the URL of one you’ve found online, Google will try to find the same image or similar ones on different sites. If the image appears in a profile, you could right-click on the image, click Properties on the menu that appears, and then copy the URL in the Address (URL) field of the Properties dialog box that appears. There is also an extension for Chrome and Firefox, which allows you to right-click on an image and select Search Google with this image. To search for the same or similar photos on Google’s Web site, do the following:

1. After going to Google (www.google.com), click on the Images link in the top navigation bar.

2. Click on the Camera icon beside the search field.

3. Either click Upload an Image to search using a photo on your hard disk or copy the URL of the image into the search field.

In using this tool, you should realize that someone could use it to find information about you. If you have a photo of yourself on one site, someone could use it to search for other images on a site providing personal information. Any photos you have on a site should not reveal any personal information about you, inclusive to logos of where you work, places you frequent, or where your children go to school. By sanitizing the personal information on sites that have photos of you, you can limit a person finding more about you than intended.

Explicit content on social media sites

Unless you’ve lived an incredibly sheltered life, you know that there’s pornography on the Internet. While some social media sites like Facebook forbid any content that is pornographic or contains nudity and/or violence, other sites allow it. Because of this, you should review the Terms of Service for sites you use to identify what isn’t included as inappropriate content for the site.

Twitter allows mature or adult content to be uploaded to their site, including media that contains nudity, violence, or shows potentially upsetting imagery like medical procedures. Indicating whether it’s of a sensitive nature is up to the person who makes it available. If you do upload such content, it’s advisable to indicate it through your account settings, so that people are warned before they see it. If you don’t want to see such content, you can opt out of the default setting to view it. To configure this, perform these steps:

1. Click on the gear-shaped icon in the upper right-hand corner of the page, and click Settings on the menu that appears.

2. Scroll down until you see the Tweet media section. Click on the Display media that may contain sensitive content checkbox so it is unchecked.

3. If you’re uploading sensitive content, click on the Mark my media as containing sensitive content checkbox so it appears checked.

4. Click the Save Changes button.

5. When prompted, enter your password and click Save Changes.

In choosing to view sensitive material on Twitter, it doesn’t mean everything is allowed. If you see any illegal content such as child pornography or other content that you want Twitter to be aware of, click the Flag Media link below the image or video to report it.

Explicit content of yourself or loved ones

Digital cameras and web cams are inexpensive, and cameras in mobile phones and tablets are commonplace, so it’s not unusual to find people creating their own sexually explicit photos and video. The self-generated images and homemade pornography might be created for personal use and meant to be shared privately between those involved or its creator and a specific person. A couple might make a video, believing it’s safe on their mobile device or computer. A lover might take a picture of his or herself, send it to a significant other via email, a sext message, or upload it to a private album or account on sites like Facebook, Photobucket, Tumblr, or Flickr. Unfortunately, such photos and video have a way of becoming public.

A 2012 study by the Internet Watch Foundation (www.iwf.org.uk) found that 88% of the homemade pornography they reviewed online had been taken from another site or location. Referred to as parasite Web sites, they get content from sites where the images were originally uploaded. It may be taken from social media sites with insecure settings, hacked accounts, chat sites, or lost or stolen mobile devices. Adults aren’t the only ones at risk of this. For over 47 working hours, they looked at 12,224 images and videos on 68 sites and focused on images depicting young people (aged 13 and 20) who were performing sexual acts or posing in a sexually explicit manner.

Sometimes images are also uploaded for the purposes for revenge. A couple may break up, and one of the parties may decide to upload the photos to a social networking site or a site that specializes in pornographic photos of an ex or revenge photos. While these can cause embarrassment for anyone, if the person in the photo is underage, it’s also illegal. In 2008, 17-year-old Alex Phillips broke up with his 16-year-old girlfriend. While together she had taken nude photos of herself and emailed them to Phillips. Now that they were broken up, Phillips decided to post them on his MySpace page with derogatory captions. When she realized the photos were online and available to the public, she called the police, who told Phillips to remove them. When he didn’t, they contacted MySpace, who removed them immediately. Phillips was charged with criminal libel, possession of child pornography, sexual exploitation of a child and causing mental harm to a child. In 2009, he pled guilty to a lesser charge of causing mental harm to a child.

Even if an underage person takes a sexually explicit photo of his or herself, it is still child pornography. In 2008, a 14-year-old girl made headlines when she posted 30 nude photos of herself on MySpace, because she wanted her boyfriend to see them. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children discovered the photos, notified a state task force, who then contacted local police. As she found out, even if you take a photo of yourself, an underage person can be charged with producing, possession and distribution of child pornography.

As discussed in Chapter 6, you can request a site to remove embarrassing or harassing content, and if you do see explicit content where the person is underage, it’s important to report it. However, removing an image or a video from the Internet can be difficult and almost impossible, especially if it goes viral and distributed on a wide scale. If an image is uploaded to a site, it may be copied to other sites, causing it to appear in multiple places. Also, if someone downloads it, they may upload it again after you’ve had the image taken down.

Predators

Just as there are predators in the wild, there are those who seek out prey on the Internet. As we’ve seen in the previous sections, there are those who will look for potential victims for blackmail, scams, and even Internet-initiated sex crimes. Of course, adults aren’t the only victims.

There are numerous studies and surveys that show how prevalent it is for children and teenagers to be solicited for sex online. According to a report funded by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 70% of girls and 30% of boys who were surveyed were approached or solicited for sex, and 79% of them experienced this on a home computer. While children of any age can become the target of a pedophile, the study (which surveyed children aged 10–17) found that the majority of those who were solicited (81%) were aged 14 or older.

Teaching children and teenagers about online safety is an important deterrent against their being victimized. Some of the important topics to cover include:

• Don’t talk to strangers. While it may seem cliché, only 14% of those who were solicited for sex knew the person. Young social network users should avoid talking to strangers. For the rest of us, be wary of them.

• If someone suggests meeting in person, don’t. In aggressive incidents, 75% of those soliciting a youth of sex suggested meeting in person.

• Talk to an adult if you have a problem. In 56% of incidents where a youth was solicited for sex, they didn’t tell anyone. This leaves them vulnerable to being groomed by a pedophile.

As we’ve stated before, it’s also important to control the information that’s posted on social networking sites. The study found that 34% has posted their real name, phone number, home address, school, and other personal information. However, it’s not just children who are at fault for this. According to a 2010 survey by Consumer Reports, 45% of social network users with children posted their children’s photos online. Looking at just Facebook users, the same survey revealed that 26% of users posted their children’s photos along with the children’s names and 7% posted their street address. Even if the names only appear in photo tags and captions, this could be enough for a predator to identify the child and start a conversation.

Even if a social media site has age restrictions, it doesn’t mean that younger children aren’t setting up accounts. Facebook limits the age of people using the site to 13 and under, but there’s nothing stopping a child from creating an account with a fake birthdate. Regardless of their age, if you have a teenager or younger child using social media, don’t allow them to be unsupervised.

The more predictable a person is, the easier it is to find them. By going on the same sites at the same time each day, it’s easier for someone to know when you’re online. They can then start regular chats and make consistent contact. Limit the time a child is allowed to go online and stagger those times so it’s inconsistent.

To make yourself available in case problems arise, ensure the family computer is in a common area of the house, such as a living room. Let them know that if he or she has a problem, you or another adult will be available to help. The other benefit of having online activity in a common area is that the child knows that you may be watching and be less likely to do something online you’d disapprove of.

IM is commonly used by predators, allowing real-time communication between two people. While a predator may meet someone in a chat room, they’ll often suggest using IM software to continue the conversation. Features of IM software can include voice over IP to allow audio communication, video chat, the ability to transfer files, and clickable links that takes the person to a site. These features allow the predator to send links to pornographic sites and coach victims into sending revealing pictures or appear in video chats. Eventually, the predator may try and arrange a meeting.

Monitoring tools

The argument of privacy versus safety is always a controversial one, even when it comes to monitoring a child or teenager’s online activity. Even if you don’t want to aggressively monitor them, you should have access to accounts. The email address used as the account’s contact should be one that you can access, and you should be able to log into the account if needed. Should the child exhibit signs of a problem, you can log on and investigate further.

Parental control systems are useful in monitoring and controlling what a child does online. Free software like Norton Family (www.onlinefamily.norton.com) allows you to monitor sites that are visited, control the time spent online, view what a person searches for online, and track activity on social networks. The premier version also provides additional features, such as the ability to monitor Android smartphones, so you can block sites and texts and monitor what apps are being installed.

If you’re concerned about a child or teenagers already having problems with their online activities with a mobile device, then you may want to use more aggressive monitoring tools. Mobile Spy (www.mobile-spy.com) provides features that allow you to monitor text messages, IM, sites visited, videos that were watched on YouTube, and calls that were dialed and received on the phone. Some of the more invasive features allow you to listen to the phone’s surroundings, track Global Positioning System (GPS) locations, and take photos using the phone’s camera without the person knowing.

Social engineering

Social engineering is the practice of using various techniques to get people to reveal sensitive or personal information. Using a variety of methods, a person might get you to reveal the information by manipulating you, through technological means or through documents you’ve made accessible. In many cases, you won’t realize it’s even happened until after you’re a victim, if you even realize it at all.

There are many ways to use social engineering to get private and confidential information. The simplest ways are very low tech. Shoulder surfing involves looking at what a person types on a keyboard as they enter a password or watch information that appears on the monitor as they type. Another is to pose as someone who’s trying to help you and ask questions that get you to reveal information. For example, if I called you at work and identified myself as part of the IT department, I might say that there’s a problem with your network account. Because it’s in your benefit for this to be fixed, and if I drew it out long enough and was convincing, you might give me your password so I can get into the system as you to “fix the problem.”

While many social engineering scams are more complex than this, getting a person’s password doesn’t have to be much more difficult than asking them. In 2003, Infosecurity Europe (www.infosec.co.uk) conducted a survey of office workers at Waterloo Station in London, England, in which people were asked a series of questions to get the reward of a cheap pen. The questions in the survey included asking a person to reveal his or her password, which 90% of office workers did willingly. Of this number, 75% immediately gave up their passwords when asked “What is your password?,” and 15% gave up their password when some basic social engineering tricks were applied, such as asking the category their password fell into and some additional questions. For example, one person doing the survey was the CEO of a company who initially refused giving the password as it would compromise security, but later said it was his daughter’s name. When asked what his daughter’s name was, he replied without thinking, thereby giving up his password.

While Social Engineering is often associated with a conversation where the tidbits of truth is slowly leaked out, it can (and often does) happen in ways you wouldn’t consider. One method is through questions that people distribute to one another via email or Facebook notes. The questions may be fun or silly to fill out and have recurring bouts of popularity, as they allow you to share information with others that wouldn’t normally come up in conversation. If you search for “Facebook notes questions,” you’ll find a number of these questionnaires. Some of the types of questions might include:

In glancing at these questions, they may seem fairly innocuous. However, if you look closer at the questions, you’ll find that some are common security questions asked when setting up an account online. If you provided me the answers, I might be able to use an email address that can be viewed on your profile page, attempt logging onto the site, and click the link saying that I can’t remember my password. By answering one of the security questions like “What city were you born in?” I could automatically obtain access, may be asked to create a new password or have a temporary one emailed to me. In the end, I now have control of your account, which could be very bad if it gives me access to your financial information, like a bank or credit card account.

Social media is a dream resource for social engineers. People post a considerable amount of information about their lives, loved ones, and interests on multiple sites. By going through this information, you can find when a person was born, their family member names, information on where they work, and their sports fans, movie buffs, and more. Individual pieces of information may not seem like much, but combined it can be somewhat revealing.

When people create passwords, they want to remember them, so they often incorporate the things they love or have interest in. As we’ll see in Chapter 10, there are a number of passwords that are easy to guess and common among people. In 2012, SplashData, a provider of password management software, compiled a list of common passwords, and in looking at these you can see that many fall into specific categories. These include:

• Keyboard rolls like qwerty, asdf, 12345

• Letter andor number combinations like 11111, abc123, or 345abc

• Names (inclusive to first names or first initial followed by surname)

• Favorites (car, team, sport, athlete, band, song, movie character, actor, etc.)

• Affiliations (including religious words like god, jesus, etc., schools and clubs)

In using these, there may be a numerical extension. For example, the end and sometimes beginning of the password would contain a number (e.g., a number between 0 and 9, 123, 69, 007, and so on) or a significant date (such as by putting a year of birth, graduation, or marriage). When thinking about your own passwords, there’s probably more than one that follows this formula.

With this knowledge in hand, now look at a Twitter or Facebook account that’s visible to everyone or belongs to someone you know. In looking through, you’ll probably find tweets or posts about their favorite team winning a game, mentions of their favorite movie, their child’s name, and so on. These things can be leading to finding what their password is.

The information you find on people’s profile pages and posts can also be compiled into more specific uses. In looking at the information a person puts in their contact information on social networking sites, you’ll see instances where their address, phone number, email address, and other personal information is available for everyone to see. In many cases, they didn’t want the information available to everyone, but mistakenly thought their security settings prevented others from seeing this.

Sites like LinkedIn are a goldmine for social engineers, as it’s designed to display information like an online resume. In addition to possibly seeing contact information, you can see the schools they attended, current and past positions with organizations, how long they’ve been working at a job, interests, groups and associations, awards, and so on.

To show how vulnerable this makes you, consider how easy it would be for an attacker to look at your LinkedIn profile page and see where you’re currently working. By using a site like WhitePages (www.whitepages.com), the person could call you at work or possibly at home. While talking to you, the attacker could pose as someone in authority to get you to reveal more information. By saying he or she is from your bank and wants to confirm information, the person could recite what you’ve published on your LinkedIn page, and then slip in a question or two like “For confirmation purposes, can I get you to tell me your Social Security Number?” Between a phone conversation and your LinkedIn page, it would be easy for the attacker to apply for an online credit card, loan, or take other measures to steal your identity.

Protecting yourself from social engineering requires being aware of potential security risks and taking steps to minimize them. Primary to this is being aware of the information you make available on the Internet, and keep in mind that strangers could have access to this information. Some tips for your safety and information security include:

• Be thoughtful about what you’re saying online. Don’t mention projects you’re involved in, answer questions that reveal personal or business information, and avoid mentioning the names of coworkers and loved ones in tweets or other public forums. If someone could use it against you or your business, don’t say it.

• Leave contact information like addresses, phone numbers, and so on blank.

• Ensure security settings on social media sites limit what strangers can see.

• Don’t accept friend or contact requests from anyone who asks. The chances of the wrong person viewing your information increase if you accept these requests from strangers.

• Review the friends and contacts you have. If you have hundreds of friends, how many of them do you really want seeing your posts?

Dumpster diving

If you’ve ever thrown something in the garbage that maybe should have been put in a shredder, you should wonder who might have access to it. Dumpster diving is a low-tech way of getting information, which involves pulling documents containing information from the trash. A person may throw out a piece of paper with a password on it, a work document, pay stub, bill, or something else containing sensitive information. One in the trash, anyone with access to the waste basket, a trash bag the janitor throws it into, or the outside dumpster can pull it out and use it. Even if the information isn’t as direct as a piece of paper with a password written on it, the information on multiple documents can be compiled into something the attacker can use.

Organizations should implement a policy that any documents containing confidential information should be shredded and not thrown out with regular trash. However, even if your business follows such policies, this doesn’t protect you from employees taking information home and throwing it out there. In the second annual Infosecurity Europe survey mentioned earlier, it was found that 80% of employees took confidential information home with them when they changed jobs. Even if an attacker didn’t have access to information at your business, it doesn’t mean that they can’t get it through current and former employees.

Trying to restrict what information an employee can and can’t take home from work can be difficult if not impossible. Many people in a workplace use tablets, laptops, and other devices that store considerable amounts of data and walk in and out of a business on a regular basis. As such, education and policy are important, so that workers take this responsibility seriously.

For employees, there is a greater need to control what they leave the building with on their last day of work. If a former employee is angry enough to leave a business with confidential information, they are also probably more than willing to share it with anyone who asks. Some may even be angry enough to start posting confidential information on social networking sites, or as we discussed in Chapter 6, uploading documents to various sites like WikiLeaks (www.wikileaks.org).

Phishing

One social engineering technique is phishing, which is pronounced as “fishing.” The term comes from the philosophy that if you cast a big enough net, you’ll catch a few fish. It involves sending out bulk email or instant messages to as many people as possible, asking them to provide information or click a link. The link often takes them to a fake Web site that looks like a legitimate site. For example, it may look like a login screen for Facebook, Twitter, PayPal, or a credit card company. You’re asked for your username and password, credit card information, or some other data that a criminal is trying to obtain. The site may require a number of questions filled out, many of which are innocuous, but buried between the questions are ones that do ask for your personal or financial information.

Phishing may also be focused on specific targets, such as individual employees or groups within an organization, which is referred to as spear phishing. For example, let’s say I know you and a couple of others in your company are in charge of social media, and I send you an email posing as the IT department. The email might state that we’re updating our records and want you to confirm the username and password of social media sites “our” company is using. Without thinking twice, you may think this is a legitimate and reasonable request and respond to the email. Even if I don’t get a response from all of the people using social media, even one response can give me everything I want.

Whaling is another variation, in which the attacker targets bigger fish within the company. The target is a senior executive or some other high-profile person within the company. By focusing on these people, there is a better chance of acquiring more privileged information that a low-level employee wouldn’t be privy to.

Context phishing can also be used to gain a person’s trust. Using this method, I look at your online activity, using sites like eBay to discover your bidding history, Facebook to find your birthday and friends, or MySpace to discover your interests. By mentioning bits and pieces of information I know about you, I can know how to gain your trust and have a better chance of your providing me additional information. By compiling enough of this information, it is possible to use the data to commit identity theft.

As is the case with other kinds of cybercriminals, phishers go where people go. As social networking sites have increased in popularity, incidents of people using social media sites for phishing expeditions have also increased. Many people will ignore or question the validity of request in their email to click a link or answer a question, because they’ve been educated to be wary of these requests. However, the same people will think nothing of doing it when the message is received in through a social networking site. The fact is, no matter what the medium, you need to be careful of the message.

Fake sites

A common ploy in social engineering involves getting a person to enter information into a fake site. The site may look like the real thing, but it’s been created to try and capture personal or sensitive information. As you log into it or enter data into fields under the guise of verifying information, it is stored and reviewed later by the criminal who runs the site. Now that he has your information, the person can log onto the site you thought you had gone to and pose as you online.

While some sites used for phishing and other scams can be quite elaborate, most are not. When you visit the site, you may notice a number of things that can make you question the site. For example, words may be misspelled or have poor grammar, images on the site may be of poor quality, or the design of the site may look different from what you’re used to. If you have been to the site before or see things that make you question whether it’s legitimate, trust your instincts, don’t enter any information, and leave.

Another way to identify a fake site is to look at the protocol being used to communicate with the Web server. A protocol is a set of rules, and in terms of networking, it is how computers communicate with one another over a network. In many cases, a browser will use HTTP to request a page or resource from a Web server, but on more secure sites, a different protocol is generally used. Secure sites like banks will generally use a protocol called HTTPS, which provides encrypted communication and secure identification of a network’s Web servers. As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, if the site is using HTTP, you’ll see in your address bar that the URL begins with “http://,” but if it’s used HTTPS you’ll see that it begins with “https://” and will show a padlock symbol next to the address bar. If the site isn’t using HTTPS but is using some other protocol, you should be concerned because the data is being transmitted over the Internet insecurely.

Fake sites for purposes other than phishing

Fake sites may also be created for criminal and noncriminal purposes. There are humorous parodies of commercial sites, and ones that are created as a form of Internet activism called cyber-activism. When considerable work is done, these may look like the real thing and can easily fool you. It isn’t until you delve deeper into the site’s content that you recognize that it’s a fake. Examples of these include:

• Police Guide FBI Records Search (www.policeguide.com/cgi/criminal-search.cgi), which allows you to enter personal data to search FBI records. Well, not really. The FBI doesn’t allow public searches of their records system, and it is obviously a joke when the search is completed.

• World Trade Organization (www.gatt.org or www.gatt.org/homewto.html). While the real site is located at www.wto.org, these sites, searching on Google, include a description of the site as the “Official web site of the World Trade Organization.” The site is one of many created by the Yes Men, who create prank sites as part of cyber-activism. A list of some of their archived sites is available at www.yeslab.org/museum.

• Apple iPhone (http://apple-cf.com.yeslab.org) is another parody from the Yes Men, but worth mentioning because it was so close to the real site that Apple worked fast at having it shut down. The site offered a “conflict-free” iPhone 4 that doesn’t use minerals from mines in the Congo that isn’t controlled by rebel groups and a free upgrade by going to Apple store on 5th Avenue.

In looking at these sites, you can see the varying levels of effort involved in creating a site that impersonates another organization. The first site offers a service to check FBI records, and although it’s obviously for amusement, it does ask you to provide information. By pretending to be a legitimate site, people are lured into a sense of security. A site gets you to enter personal data by offering something you really want or a service that benefits you, enticing you to give up information you’d normally keep private.

Although the Apple iPhone site wasn’t built for the purposes of scamming people out of money, there are a number of online scams that are for this purpose. When a new iPhone is released, people are enthusiastic to upgrade, and offers have appeared on the Internet that get people to pay for an upgraded phone prior to its release or when they were sold out. It’s a common element of many scams to offer something too good to be true.

Even if fake sites aren’t designed for purposes of phishing, scams, or other criminal endeavors, they can cause considerable problems for a business. For the iPhone site, Apple needed to pay legal fees to have it shut down and dedicate resources to address allegations on the site. These and other fake sites can cause public relation issues for companies by publicizing unethical or unpopular business practices or by publicly embarrassing them by portraying them as unprofessional or foolish.

Fake or shortened URLs

When you do visit a site, you need to be careful that the site you’ve visited is the correct one. For example, let’s say you click on a link to take you to LinkedIn. If the address bar at the top of the browser starts with www.linkedin.com, you know you’re at the right place. However if it looks different, showing something like http://linkedin.example.com or http://[email protected], you are not on the correct site. You’ll notice that the domain name in these URLs is example.com, meaning you never reached the LinkedIn site. In such cases, you should immediately leave the site and not enter any username or password.

For fake sites, you’ll often find that a domain name similar to the real one is used. For example, if you saw a link for www.linkedin.cm, you might miss that the URL doesn’t use the .com domain suffix. It’s actually using the .cm suffix, which is reserved for sites registered in Cameroon. Another common ploy is to use the domain suffix of the real site but use a slightly different spelling to the name. Unless you’re paying attention, you might miss that the link is taking you to www.linkdin.com instead of www.linkedin.com.

Although the suffix of a domain may be an indicator, this isn’t always the case. It’s important to note that many legitimate sites will register domain names that don’t end in .com, or ones that aren’t related to the country the business actually resides in. For example, you may have seen domains ending in the suffix .tv, which are often used by television stations or sites with rich media. The .tv domain suffix is a country code for the islands of Tuvalu, which is a Polynesian island nation that is 26 km2 in size, and as of 2013 has an estimated population of 10,698 people. In 2000, they started leasing the domain name .tv to Verisign for $50 million in royalties over a 12 year period, which was then renewed under undisclosed terms until December 31, 2021.

Before clicking on any links, it’s always a good idea to take a moment and see where it will take you. If it’s a link on a Web page, you can hover your mouse over it and see the URL of the link in your browser’s status bar or in a tooltip that displays beside the link. Depending on the email program you’re using, the same will occur if you’ve received a link in email.

As we discussed in Chapter 4, shortened URLs can be used to make a long URL smaller. You may see a site starting with tinyurl or bit.ly, such as http://bit.ly/10TjJ3v. When you click on it, you find yourself taken to a site with a different and significantly longer Web site address. Generally, there is no problem with this. The reason it occurs is because the URL is being resolved by a site like TinyURL or Bitly. Clicking the link takes you to their service, which resolves that URL to one in its database, and redirects you to the proper site. The shortened URLs make it easier when you’re making a post or tweet and limited to a certain number of characters. However, it also masks where you’re going. If you were to click the link, you couldn’t be sure if you were going to what appeared to be a legitimate site, or one that a hacker setup to obtain information or install malware to your system. If you believe a site isn’t legitimate, you should contact the shortened URL service and notify them, change any passwords you may have entered on the site, and run anti-malware software on your machine.

Norton Safe Web

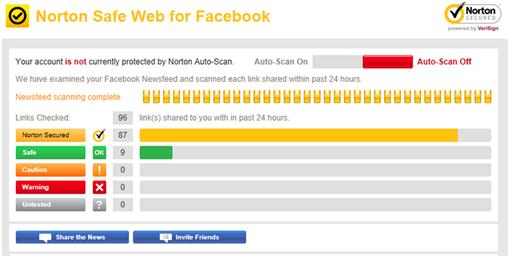

A useful tool for checking links on a page or newsfeed is Norton Safe Web, which is available through Facebook’s App Center at www.facebook.com/appcenter/nortonsafeweb. In visiting the page, click on the Go To App button. When using the app for the first time, you’ll be asked to allow it to have certain permissions on your account. As seen in Figure 7.2, a page will display that analyzes the links that have been shared in the last 24 hours, showing which are safe and what ones you should be concerned about. By hovering your mouse over the red slider in the upper right corner and holding down the left mouse button, you can move the switch to the Auto-Scan On position. This will set the app to automatically check any links on your newsfeed.

When Norton Safe Web automatically scans your wall, it will post an update to tell you if any malicious links have been detected. If it’s something you posted, you should delete it from your profile. If someone else posted it, you can then use a Warn Your Friends option to notify them about the link. If nothing malicious is found, the app will post a message every 30 days to notify you that your wall is safe.

Anti-phishing protection in browsers

Newer versions of browsers have features that will detect whether a site has been reported as a known for phishing or malware. Malware is programs that contain malicious code that’s designed to damage or disrupt your computer, gather private or sensitive information, and may even download additional software or viruses. Browsers like Internet Explorer and Firefox will compare the URL you’re attempting to visit to lists of reported sites and will block you from going to the site if there’s a problem. Browsers like Opera and Google Chrome will also use sandboxing techniques, in which the browser is isolated from other information on your computer. They will also do such things as block access to a site if the URL in a certificate doesn’t match the URL of the site you’re visiting. If the two don’t match, then this is a sign that the site you’re visiting is a fake one.

Internet Explorer provides a SmartScreen Filter feature that runs in the background while you’re using the browser. In versions 7 and 8 of Internet Explorer, this was called a Phishing Filter. When you attempt to go to a site, it will compare the URL to a list of sites that have been reported to Microsoft that’s stored on your computer. It will then determine if the site has any features that are common to phishing sites, and (if you’ve permitted it) may then send information to Microsoft to check the site against an updated list of problem sites. If the site is on a list, the browser displays a warning page, and you can then choose whether to continue to the site.

By default, SmartScreen Filter is not turned on, so to use it you need to activate it in your browser. To do this, you would follow these steps:

1. In Internet Explorer, click on the Tools menu.

2. Select SmartScreen Filter from the menu, and click Turn on SmartScreen Filter.

3. When the dialog box appears, make sure that the Turn on SmartScreen Filter (recommended) option is select, and click OK.

If you don’t have SmartScreen Filter turned on, you can still check the site by doing the following:

1. In Internet Explorer, click on the Tools menu.

2. Select SmartScreen Filter from the menu, and click Check this web site.

3. When the dialog box appears, click OK.

4. Wait for the site to be compared against a list on Microsoft’s site to determine if it’s unsafe. A dialog box will appear showing the result.

Google Chrome provides features that will check a site and display messages if you are visiting an unsafe site that contains malware or is suspected of being a phishing site. If you want to continue to the site, you have that option, but it is recommended to leave and find the information you’re looking for on a safe site. By default, phishing and malware detection is turned on. If you don’t want to use it, you need to go through the settings to turn off this feature. To confirm that it’s turned on, do the following:

1. In Google Chrome, click on the menu button (which has three strips on it) in the upper right of the browser.

3. At the bottom of the page that appears, click Show advanced settings.

4. When additional settings appear on the page, look in the Privacy section and ensure the checkbox labeled Enable phishing and malware protection is checked.

Mobile devices can also benefit from security apps that will scan sites for malware and phishing risks. As we saw in Chapter 6, Lookout Security and Antivirus is a tool that can be installed on iPhones and Android devices. One of the premium features is Safe Browsing mode, which scans sites for malware and phishing risks.

Hacked accounts

Hacking is a mainstream term that has come to refer to anyone who breaks into a computer system. While for ease of understanding we use the term throughout the book, the original definition of a hacker referred to a computer enthusiast. It was someone who would hack away at a keyboard, programming, or working in some other way on a computer. A cracker is what most people are actually referring to when they discuss hackers. A cracker is someone who will try to crack the security of a system, breaking into computers or cracking passwords.

There are many laws that have been designed to deal with the unauthorized access of systems and data, and the damage that can result from such actions. In the United States, individual states have specific laws that address the issues of unauthorized computer access, identity theft or fraud resulting from accessing data, destruction of data, and other issues related to hacking. In terms of Federal law, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) of 1986 has been amended numerous times, inclusive to the enactment of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001. The CFAA makes it a federal crime to access a computer without proper authorization and came under additional scrutiny in 2013.

In 2011, Aaron Swartz, the cofounder of Reddit, was arrested for downloading millions of academic articles from a database using a guest account. If that doesn’t seem like hacking, you would have been in disagreement with the government. He was arrested by police and a US Secret Service agent. While many of the articles were public domain, there was also copyright material, which they believed Swartz planned to share via peer-to-peer networks. He also spoofed the MAC address of his laptop, as MIT had used the number to block the computer from the network. He was arrested on counts of wire fraud and violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which could have resulted in a million dollar fine and up to 35 years in jail.

In 2013, Aaron Swartz committed suicide by hanging himself. No suicide note was found, so there is no indication as to what his specific reasons were. However, one can only imagine the stress of facing those kinds of charges. As a result of his death, an amendment to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act has been proposed that will prevent people from being charged for violations of terms of service, contracts, or other agreements.

Hacking attempts can cause serious problems for an organization. While many people associate hacking with accessing the protected systems of large organizations, hacking social media accounts can have far-reaching implications. On April 23, 2013, the Twitter account of the Associated Press (@AP) was hacked, and a tweet was sent out saying that there had been two explosions in the White House, and Barack Obama had been injured. The incident caused US markets to plunge within minutes of the tweet. Associated Press used their Twitter accounts to tell everyone that the tweet was false, and that the account had been hacked. They advised people to ignore tweets from the accounts, as they’d been compromised. A hacker group called the Syrian Electronic Army later claimed responsibility.

An example of how hacking works

In the case of the parody news site the Onion (www.theonion.com), the hackers used phishing attacks that were focused on the email accounts of staff members. Employees received an email that had a link to the Washington post, which seemed to have a story about their organization. The link eventually took them to a page that asked for their Google App credentials, before redirecting them to a Gmail inbox. Once the hackers had access to a Gmail account, they sent the same phishing email to staff. Because it seemed to come from a trusted source, people were more willing to click the link. Unfortunately, one of those who fell for the ruse had access to the Onion’s social media accounts.