10

Managing a Unified World

Global Order out of Local Institutions

While previous chapters have focused on the United States, similar economic transitions are under way in other countries throughout the world. East Europe, Russia, and China are struggling to make market systems work, and the European Union is beginning to dismantle its welfare state. Even Japan, once thought to be invincible, is being forced to free its economy from overregulation and social conformity.

Just as the New Management uses a wholistic perspective to view organizations as complete socioeconomic systems, these global changes can be best understood by seeing the Earth as a whole system in its own right. Today, a fragmented world is coming together as the electrifying force of knowledge, technology, and capital flows instantaneously around the globe. Throughout history the idea of a unified world was unthinkable. But just within the past few years the Earth has been integrating before our eyes.1

In 1994, the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, which includes the United States, Japan, China, and fifteen other nations, making up half the world’s economy, agreed to eliminate all trade barriers over the next two decades. The European Union is planning to introduce a common currency by the year 2000 as it expands to include almost one billion people. And the leaders of thirty-three nations pledged to unify economically the American continent from Alaska to Argentina by the year 2005. In a decade or two, the same self-interested cooperation now driving the growth of these regional blocs should merge them together into a single global market. Akio Morita, former chairman of Sony, has called for the removal of all trade barriers between North America, Europe, and Asia.2

Note: Portions of this chapter are adapted from William E. Halal and Alexander Nikitin (of the Russian Academy of Science), “East Is East, and West Is West,” Business in the Contemporary World (Autumn 1992), pp. 95–113.

This chapter offers a global perspective to help managers guide their organizations through the complex world system that is now evolving.3 We examine the revolutionary forces that are integrating the Earth into a global order and others that are creating global disorder: both the unification of markets and communications, as well as the disintegration of corporations and governments into a maze of global networks. The emerging global economy is becoming a churning ocean of small enterprise operating across diverse cultural regions, producing a tidal wave of creative destruction that could sweep away the comfortable communities of the past. An empirically grounded framework shows that this dilemma of capitalism versus community could be resolved as managers around the world create a human form of enterprise.

My guiding premise is based on the synthesis described in Chapter 4 but carried to a global level. Today’s upheaval is merely the onset of a profound transition to a new economic order governed by two central imperatives: markets, entrepreneurship, competition, and other principles of enterprise are essential to manage an explosion of complexity, while cooperation, human values, the public welfare, and other ideals of democracy are also being adopted because it is equally important to integrate enterprise into a productive, harmonious whole.

Thus, the most distinguishing feature of the world system seems to be synthesis: the synthesis of economies into a unified global market, the synthesis of democracy and enterprise, and—in time—the synthesis of capitalism and socialism.

THE DILEMMA OF CAPITALISM VERSUS COMMUNITY

The fall of communism has made it clear that markets will dominate the new economic order, but the abandonment of central planning and welfare states is opening a Pandora’s box. Without the support of big government, people are being left to struggle alone with unemployment, poverty, conflict, and other social disorders, causing mounting insecurity and political unrest. Thus, the same forces that are decentralizing corporations into internal markets are decentralizing governments as well, posing an urgent need for some way to create civil order. How will civilized communities be restored in a decentralized world governed by capitalism?

This dilemma is exacerbated by the collapse of faith in the familiar old ideologies that guided nations through the past epoch with good success. With the U.S.S.R. now defunct and the United States struggling through an identity crisis, the lack of superpower leadership has left a vacuum of power, ideas, and moral guides at the very time when the world is facing Herculean new challenges. To avoid chaos, a new paradigm of political economy must somehow be formed that allows us to make sense of today’s radically different global realities. The CEO of Japan’s NEC Corporation has said: “It won’t be easy because nobody has really come to grips with the shift to an information economy.”4

This critical need is not helped by the common belief that the collapse of communism proves that socialism is dead and capitalism reigns triumphant. Yes, the era of central planning is over, but markets are not the same thing as capitalism. The competitive strength of Japanese business flows from a collaborative type of corporation called a “Human Enterprise System,” and other nations also have widely differing market economies.5 The real question is what type of market would be best in post-Communist states—and even in Western nations like the United States itself?

Challenge to the East: Inventing Post-Communist Markets

A serious example of this dilemma can be seen in the former Communist bloc. There is little doubt among East Europeans and Russians that there is no going back to the old system of central planning and one-party politics—the “Old Socialism.” However, these nations have communitarian cultures that encourage social welfare and economic security, and so the abrupt shift to a market system based on competition for personal gain has left people unable to cope with risk and inequality. Now that the euphoria of overthrowing communism has faded, these once functioning societies are suffering severe poverty, crime, and alienation as an overdose of raw capitalism threatens the body politic.

Even East Germans, who were expected to adapt immediately because of their ties to West Germany, now often long for their socialist roots. Polls show that only 30 percent of East Germans support the policies of their Western counterparts. Here’s how many see the change: “The revolution benefited only 10 percent of us,” and “I realize to my deep resentment that we have lost something of much more value.” One person summed it up this way: “You may have freedom in the West, but we had security in the East, a feeling of being cared for. It is less cutthroat here.”6

The tenacity of this “socialist ethic” is proving a major obstacle to economic reform, as seen in Box 10.1. On the supply side, a frenzy of new ventures has been unleashed by entrepreneurs and former Communist officials, but the privatization of state enterprises has faltered because of limited economic prospects, the lack of infrastructure, and poor business skills. Now great plants that were once productive backbones of the old Soviet economy are running at a fraction of their capacity, and workers sit idle.

On the demand side, the loss of productivity has plummeted living standards to half of the meagre lifestyles Communists once enjoyed. A middle class is emerging that is eager to buy cars, televisions, and the other goods of a consumer society, but those who can afford such luxuries amount to a mere 10 percent or so of the population while one-third or more are impoverished.7 Understandably, resentment is mounting as people see the old Communist elites simply replaced by capitalist elites with still more wealth and privileges (see Box 10.1). Peter Reddaway, former director of the Kennan Institute for Soviet Studies, described the problem as follows:

Why is shock therapy not working? Because Russia’s deeply political culture is highly unsuited to free markets. Yeltsin now realizes he made a mistake in opting for a rapid transition to capitalism.8

Meanwhile, the Russian economy is being run by former Communist apparatchiks, Mafia bosses, and financiers seeking their own fortunes rather than creating jobs and goods, reminiscent of the “robber barons” of American capitalism. George Soros, the famous Hungarian-born American financier, called it “robber capitalism.” It is ironic that seventy-five years of Soviet propaganda about the “evils of capitalism” were never really believed by the Russian people until they tried it themselves. Now the impoverished proletariat that Marx warned of is rising in his own homeland.9

Of course, the East Europeans are doing better generally. And some Russians are optimistic because they think the worst is over, so these problems could be alleviated in time.10 But many others think the nation is in serious trouble. The chief economist of the World Bank noted that “zealous reformers underestimated the task,” and a Russian politician worried, “The situation is worsening. Some other way must be found.” George Soros is even more dour: “I was hoping to see a market-oriented democratic system. That attempt has basically failed. [The present situation] is creating a tremendous sense of social injustice.”11

By embracing the icon of capitalism held up by the West, communism has shed its old ideology only to submit to a new ideology. Many Russians bitterly condemn the blind faith in capitalism that now imprisons them as badly as communism used to. George Bernard Shaw put it best: “Revolutions have never lightened the burden of tyranny. They only shift it to another shoulder.”

Challenge to the West: Inventing a Human Capitalism

While the virtues of capitalism were being promoted to cure the Russian malaise, the same system was suffering in the land of its chief proponent. America has entered a period of social decline because it seems too concerned with free markets, profit making, and other capitalist ideals being advocated for socialists.

No one denies that the American system has extraordinary virtues. U.S. citizens enjoy an exceptional degree of freedom, which has flowered into a vibrant, creative culture and one of highest living standards in the world. These strengths have long attracted a flood of eager immigrants to American shores, and they have inspired today’s revolutions around the world.

But freedom entails a price, and the price Americans pay is the absence of that essential sense of community. The competitive stress, lack of social support, and sheer materialism of American life are major causes for the rampant crime, drug use, violence, and other social problems that are the highest in the world; that’s why the “Land of the Free” has more of its people in jail than any other country. One study ranked the United States’ overall quality of life at the bottom of a list of industrialized nations.12

Yes, productivity and corporate profits are doing well, but layoffs have demoralized employees, people are overstressed, loyalty is dead, wages are still falling, most wives must now work, and marginal workers struggle to survive. In the midst of all this loss, CEOs are awarding themselves lavish pay increases, as BusinessWeek announced record corporate earnings: “Hot Damn! Profits surged another 45 percent.”13 The resulting disparity of incomes between the top and bottom levels of American society exceeds that of all other industrialized nations, and it has returned to the levels reached prior to the Great Crash of 1929.14

Now, it is true that income differences are unavoidable, and profits are needed for capital investment. But without addressing such mounting concerns, today’s upbeat faith in the Old Capitalism may prove a temporary lull in the long decline of America’s economic dominance. During the past three decades, the share of worldwide sales by U.S. firms fell from 83 percent to 38 percent in autos, 71 percent to 11 percent in electrical goods, and 74 percent to 21 percent in steel. Even computer sales fell from 95 percent to 70 percent.15 Since 1985, the American dollar has declined 70 percent against the Japanese yen and 60 percent against the German mark.16 Can this system thrive in a Knowledge Age that demands the support of educated, motivated people?

The same loss of social support is occurring in government as the Republican Revolution rolls back the federal programs that have been relied upon since the New Deal. Of course, this is an indispensable part of the historic move to decentralize all institutions for a new era. But decentralization cannot simply abandon people to fend for themselves. Some form of local control must be devised to take up the slack left by eliminating federal regulations, social assistance, and other forms of support. Pious claims that this will be done by “the market,” the “states,” and “voluntary institutions” are little more than wishful thinking.

As shown in Box 10.2, the resulting loss of confidence over government, corporations, and other institutions has caused the American system of political economy to be widely questioned as well.

The Democratic Party does not show much talent for exploring new directions, and the Republican Revolution seems destined to roll on because it has history behind it. Thus, a serious question is being raised: How will Americans avoid the trauma that seems likely as a harsh economy and the dismantling of federal programs leave the nation bereft of social support?

A similar conflict is seen in other Western nations that also practice a more pure form of capitalism. The Thatcher Revolution may have halted the growth of the welfare state in the United Kingdom, but polls show the British people are concerned that crime, greed, and poverty have replaced the qualities that made England a great civilization, and the economy remains weak.17

These problems are not as dramatic as the collapse of communism, but they are also serious and they stem from the same cause—outmoded economic beliefs. The ideological flaw in capitalism is the wishful fantasy that rugged individualism in a struggle for profit will somehow be sublimated into healthy progress by the magic of an invisible hand. This may have worked in an industrial past, but it ignores that vast realm of human and social realities that now drives a knowledge-based economy.18

The Ideological Crisis of Our Time

These problems are formidable because they emanate from a profound ideological crisis facing the entire globe that is most clearly seen in Russia and the United States. Historian Charles Maier finds that both the collapse of Soviet Communism and the decline of American capitalism are a result of the same historic transition to a new era that is rendering all past ideologies obsolete.19

There is an intriguing symmetry to these dilemmas of East and West that is seldom understood. Both socialism and capitalism produce serious distortions, but in opposite directions. Generally speaking, socialism is in crisis because it bought secure but meager lives at the expense of freedom; but capitalism is in crisis because it has bought a prosperous freedom for some at the expense of security and community for all. Socialism suffers from scarcity, while capitalism suffers from overconsumption. Socialism produces angry dissidents, capitalism produces crime and lost souls.20

Even moderate nations are struggling with this dilemma. Almost all European governments are under extreme economic pressure to dismantle their welfare states and to rejuvenate enterprise. For instance, Italy, Spain, and France are running massive annual government deficits. Germany has inflated wages to almost twice the levels of the United States and Japan, so capital investment produces less than half of normal returns. The CEO of a German company said: “We cannot go on supporting high wages and benefits. Either we change fast, or we do not survive.”21 In Japan, the collapse of the “bubble economy” is forcing a move to accept foreign competition, reduce regulation, and create more dynamic companies.22

The conflict between capitalism and community is not so easily resolved, however, because these nations are also under enormous political pressure to continue supporting their citizens. In France, 54 percent of the public wants more state control of the economy and only 11 percent wants less. A German businessman said: “We understand that poverty and other social ills are morally unacceptable and economically harmful.” The Japanese share a similar view: “We simply cannot fire people,” said Norio Ohga, CEO of Sony. “It would only contribute to the worsening of the economy, and we really can’t afford that.”23

The same confusing dilemma persists in other regions. Latin America suffers from chronic political unrest because wealth is so concentrated that a form of monopoly capitalism often exploits an impoverished working class. Development in the Middle East has stalled because free markets conflict with Islamic principles that require serving the community.

ECONOMIC IMPERATIVES OF THE INFORMATION AGE

It is easy to be pessimistic over the enormity of this challenge, but the imperatives of the Information Revolution seem to be driving nations toward a new global order based on enterprise and democracy that may resolve the conflict between capitalism and community. Here’s how Lech Walesa explained the way this revolution occurred in Poland: “How did all these reforms appear? The result of computers, communication satellites, television.”24

A Global Network of Local Enterprise and Community

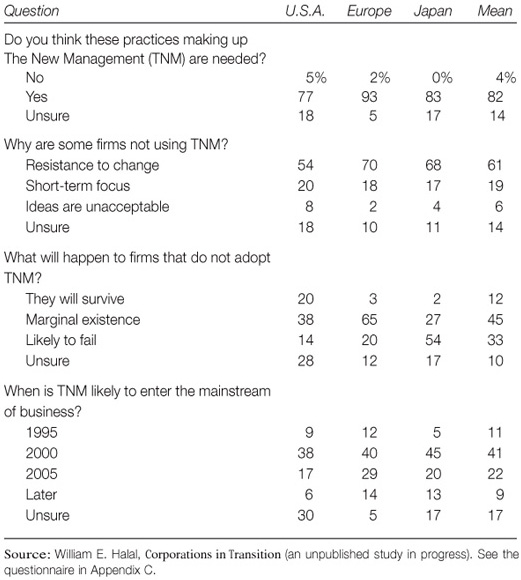

Chapter 3 showed that these same forces of democracy and enterprise are also transforming organizations. This is happening not only in the United States but also throughout the globe. European companies, such as ABB and Siemens, are being restructured to spur entrepreneurship, while the virtues of corporate community were showcased as Japanese firms captured foreign markets by cultivating harmonious working relations. Table 10.1 shows that American, European, and Japanese managers tend to agree that this trend toward a New Management is likely to enter the economic mainstream between 2000 and 2005.

As a result, corporations are becoming global entrepreneurial networks organized into pockets of local community. They now operate hundreds of internal enterprises internationally (such as ABB’s 5,000 profit centers), each forming collaborative alliances with foreign suppliers, distributors, and other business partners to raise capital, launch new ventures, acquire technology, and gain access to local markets. These complex operations are managed by an international class of professionals drawn from all over the world who can adapt to a diverse tapestry of politics and cultures by working effectively with local employees, unions, and governments. Thus, a seamless web of entrepreneurial community is increasingly joining and rejoining over a worldwide information grid to tame a complex, changing global society, as shown in Box 10.3.25

Governments are also moving in this same direction. In 1994, voters in Italy, France, Sweden, Japan, Canada, and the United States revolted against political systems that ruled the cold war era with cumbersome regulations, poor services, high taxes, and corruption. U.S. Congressman Robert Andrews acknowledged, “We are in the midst of a middle-class political revolution. The public is absolutely right. Government is out of control.”26

Caught between political opposition to raising taxes and cutting services, growing deficits are now forcing the restructuring of government throughout the world in roughly the same way that business has been doing: by privatizing operations, introducing competition to improve services, and collaborating with public stakeholders.27 These forces are also disaggregating nations into smaller communities. The number of independent states has doubled in the past few decades, and some claim the world will hold a thousand nations soon, each with numerous independent regions and cities. Henry Cisneros, U.S. secretary of housing and urban development, says the need is to “decentralize with a vengeance.”28

The emerging role for government is to provide a cooperative economic infrastructure that supports sound economic growth. As a global economy enables firms to locate anywhere, governments are under increasing pressure to attract responsible business formation by providing low taxes, information superhighways, minimal regulations, access to advanced technology, educated workers, product markets, and social amenities.29 Cultivating this new role made Singapore one of the most prosperous regions of the world. With no natural resources and a small population, the city has attracted three thousand corporations by creating the most advanced public IT system and economic infrastructure anywhere.

Further, the need for both enterprise and social support is encouraging a symbiotic relationship between these two pivotal institutions, which can be seen in the wave of business-government partnerships. Governments are eager to help business rejuvenate their economies, and business can only thrive in healthy societies. “The government can’t do it by itself,” said Governor George Voinovich of Ohio. “The private sector has to get involved.”30

Remember that this emerging form of economic cooperation is not altruism but mutual self-interest that benefits all parties. Ray Norda, former CEO of Novell, called it “coopetition—cooperating, often with one’s rivals, out of enlightened self-interest.” In fact, it is precisely the heightened level of competition that drives a corporate community together. The battle for economic survival is no longer waged between single firms, but takes the form of competition between these “clusters of entrepreneurial community.”

It’s obvious that only a leading edge of progressive managers are adopting these innovations, especially the idea of corporate community. And there will always be a crucial role for the United Nations and other international institutions. But the most likely scenario for maintaining social order in a complex, changing, decentralized global economy is through cultivating community among local institutions.

The revolutionary forces described in this chapter and the many examples cited in this book highlight the power of today’s technological earthquake that is causing a global upheaval. Information technology exerts a force as revolutionary as that of industrial technology two hundred years ago. The Information Revolution requires free enterprise to manage a rising tide of complexity, while economic cooperation is also necessary to unite this complexity into productive communities. Driven by these twin demands, managers around the globe are transforming corporations and governments into the same form of entrepreneurial, collaborative institutions needed to maintain a civilized although turbulent world.

The Tendency Toward Divergence and Convergence

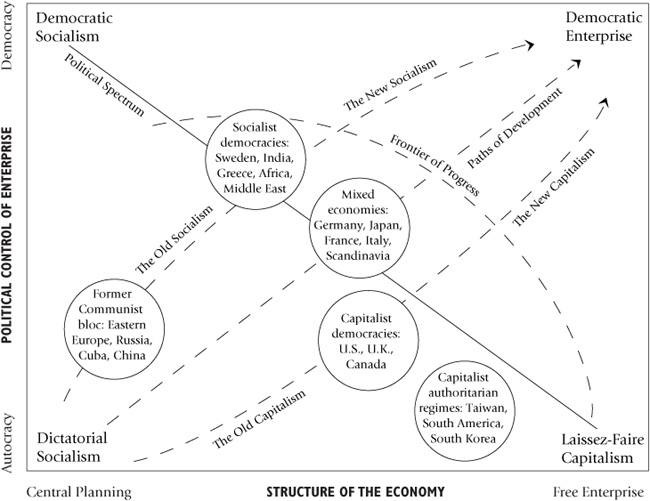

I do not claim that this new economic system will become universal. Figure 10.1 depicts how the relationship between enterprise and democracy forms complex, changing patterns in response to two opposing trends: a tendency toward divergence caused by differences in cultural values, and a tendency toward convergence caused by the common imperatives of information technology.31

Studies indicate that nations develop diverse economic systems that are compatible with their cultures. Figure 10.1 shows how countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Taiwan, South Korea, and the South American states favor entrepreneurial freedom and other economic values, which characterize the lower-right end of the political spectrum. At the upper-left end of the spectrum, China, Russia, East Europe, Sweden, India, Africa, and the Middle East lean toward social values like security and public welfare. It is hard to categorize nations neatly, and all this is changing, of course. But culture, one of the most powerful forces in the world, seems to produce these broad, general patterns.32

While wide variations will remain, over the long term the imperatives of information should continue to urge most nations toward a roughly similar combination of democracy and enterprise that integrates social and economic values. The attraction toward this center position is illustrated by the fact that the most productive economies tend to favor a combination of enterprise and collaboration; Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy, Scandinavia, and Japan have created the highest overall quality of life in the world during the past few decades, although they too are now facing new adjustments. A European manager explained:

The competitive battle senior managers face is a struggle among [market] systems, each with its distinctive set of values. I believe our European system of alliances among workers, suppliers, distributors, and government is better suited to meet the economic and social challenges ahead.33

Although differences will flourish to suit cultural tastes, this diversity is likely to evolve into variations on the same organizing principles because all nations are pressured by common economic realities of the Information Age. The instantaneous flow of electronic capital around the globe is now forcing interest rates and wages to converge and governments to adopt similar economic policies. In 1995, for instance, the Mexican peso fell precipitously because of a large trade deficit, while the Japanese yen climbed due to a trade surplus.34 This convergence may be most pronounced in the developing countries that are searching for a middle way. Mujmul Saqib Khan, a Pakistani ambassador, claims that “leaders of developing countries will blend capitalist and socialist models.”35

This perspective on the emerging global economy, then, offers managers some insights into the complex problems they must solve around the world. Not only must they learn how to operate across wildly different economies, laws, currencies, and cultures, they must also adapt to a wide variety of deeply rooted political ideologies, which should increasingly combine various blends of enterprise and community. While this global order is sure to grow even more intricate, it should help to keep in mind that this confusion can be sorted out by using New Management concepts. I hope this chapter shows that the same forces are at work in a global context.

FIGURE 10.1. THE EVOLUTION OF POLITICAL ECONOMY.

These trends are as yet limited to an avant garde, of course, but their implications are profound. As shown in Figure 10.1, the concept of Democratic Enterprise may eventually integrate socialism and capitalism into compatible but somewhat different versions of this same overarching global paradigm. We could then witness a breakthrough in political economy that fosters the formation of robust local community while simultaneously creating a more productive type of enterprise. A new economic epoch is at hand in which enterprise and human values are efficient, so such a system may become commonplace, making it possible for managers to operate more easily throughout a truly unified global economy.

I realize that there is much cynicism over such prospects, but consider the changes the Industrial Revolution brought to the average agrarian peasant, who suffered a short, grueling life of labor in the fields under servitude to a dictatorial monarch. Average people living in developed nations today certainly bear hardships, but they are white-collar workers enjoying the freedom of market economies and democratic government. Why should the Knowledge Revolution be less dramatic?

THE EMERGING SHAPE OF THE NEW ECONOMIC ORDER

Projections of these trends provide some intriguing forecasts that defy conventional wisdom.

Democratic Enterprise in the East: A New Socialism?

The main obstacle facing the former Soviet bloc is today’s antisocialist fervor, which blinds us to the more subtle truth. As we have shown, most people in socialist cultures, and even many Americans, dislike the harshness of capitalism and prefer the human values that have inspired socially oriented economies now thriving in Western Europe, Japan, and other leading economic areas. That’s why half the world moved to socialism in the first place.

The key to resolving the crisis gripping Russia and Eastern Europe, then, is to recognize that socialism was not an aberration but an important advance. In the heat of today’s reforms, it is easy to forget that socialist philosophy was once praised as a constructive response to the exploitation of labor, monopoly control of markets, and other injustices of early capitalism. Communism was a harsh system, certainly, but the capitalism of the robber barons was equally harsh, and even the capitalism of today can be harsh. What morality tolerates a system that rewards people like Michael Milkin with more than $500 million per year while a quarter of its infants live in poverty? The present love affair with capitalism is likely to run its course in a few years as excesses mount, taking the political cycle back toward social policies.

Rather than expect socialists to abandon their heritage, therefore, it is more useful to view the Russian dilemma as roughly comparable to the transition Americans experienced during the Great Depression of the 1930s, which threw the viability of capitalism into question. The Depression resulted from a severe failure in the market system, but it was corrected with insured savings, unemployment benefits, and other social welfare programs that stabilized the American economy.

Economic progress in Russia lags behind that of the United States by about fifty years, so the nation is making a similar transition at roughly the same point in its development. Just as Americans did not abandon capitalism during the Great Depression but corrected its flaws by adopting some elements of socialism, Russians may in time develop an advanced form of socialism incorporating markets and democratic enterprise—it could be thought of as a “New Socialism.”

Many economists dispute the concept of a “Third Way,” yet some trends are moving in this direction. Polls show that most Russians and other post-Communist people favor a democratic, market socialism. A Czech politician said: “We do not talk about ‘social markets’ to avoid headlines, but the condition for our success is to keep public support.” In Poland, the Democratic Left Alliance that won the 1993 elections based its success on combining the best features of socialism and capitalism: “The big mistake that Solidarity made was to throw out everything from the past,” said the party chairman. And a Chinese official said, “Capitalism doesn’t have a patent right over markets. We’re trying to establish a socially oriented market economy.”36

Just as markets are not necessarily capitalism, then, socialism is not necessarily government planning. The concept of Democratic Enterprise offers a logical solution to the current Russian crisis because it could provide the advantages of free markets while retaining some sense of harmonious social control. In terms of traditional socialist thought, this type of socially guided market economy would serve the public welfare through decentralized planning, conducted at the level of the individual enterprise rather than the state, and managed democratically by stakeholders.37 The main obstacle to revitalizing the post-Communist bloc is building viable institutions, and this approach could draw on their communitarian culture to form productive business corporations and other social institutions.

Let’s sketch out what this system might look like. The private sector in Russia should continue to be managed with free markets, but this is basically a socialist society, so government could assist with employment, medical care, housing, and pensions to buffer its citizens from the vicissitudes of markets. It might also be best to maintain strategic control over banking, utilities, transportation, and other quasi-public industries, either through regulation or state ownership. A 1995 poll of 4,000 Russians found that 66 percent want more state control of the economy.38

The most crucial strategy would be to help Russian managers develop a form of democratic governance in which workers, business partners, government, and customers share control of organizations. This crucial step would allow a fresh application of socialist values to form an acceptable type of communitarian enterprise able to thrive in a vibrant market economy. Box 10.4 shows typical practices.

The path these nations follow is certain to be messy, and today’s raw capitalism will likely continue until the public demands reforms, following the American experience. However, opinion polls show the following probabilities for three alternative scenarios: Russians believe there is a 22 percent chance that the nation will develop an American type of capitalism; a 15 percent chance that it will revert back to central controls; and a 63 percent chance it will follow the middle path of Democratic Enterprise. Other studies show similar results for China.39

Democratic Enterprise in the West: A New Capitalism?

An interesting feature of this thesis is that the capitalist world may move toward a roughly similar system, although it would be viewed in terms of Western values and it would be approached from the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 10.1.

America is a crisis-driven society, so the driving force for such a difficult change seems likely to be the identity crisis that grips the United States. But the American potential for meeting new challenges is enormous. After Pearl Harbor forced America into World War II, the United States emerged as the most powerful nation in the world. When Sputnik launched the space race, America soon landed the first man on the moon. And the Arab oil embargo produced such a burst of energy conservation that the United States became glutted with cheap oil. The demand for change during the 1992 and 1994 elections suggests that a similar surge of reform could emerge over such ideas as “Human Capitalism” or a “New Capitalism.”

Americans are practical people, and a continuation of today’s social decline may convince them that the nation’s obsession with profit, capital investment, taxes, and other economic policies misses the real issue. The great need facing the United States is to make a subtle but crucial shift from a capital-centered system to a human-centered system that would create a sense of common purpose to unify its institutions and the nation. Herbert Stein, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, says America needs to establish a new goal of “improving the quality of life.”40

Some movement has been building in this direction for years. As summarized in Box 10.5, the trends reported in this book show that many American managers realize that a collaborative form of business is needed because economic success hinges on gaining the support of their various stakeholders. Why should tough-minded executives want to do this? Because it is more productive.

Moreover, business is the leading institution that sets the tone for society today, so its example could encourage government, education, and our other social institutions to do the same. The crisis in American education, for instance, could be resolved as public schools move further along the path toward internal markets and corporate community being blazed by innovative corporations. A dozen or so states allow parents to choose schools; roughly twenty states now permit teachers to form charter schools, and many offer merit pay. Likewise, participative governance is being adopted to manage schools by bringing administrators, teachers, and parents into policy making. In short, the principles of the New Management are at work revitalizing education.

A powerful new form of government is also needed that assists the responsible operation of a fast-moving, high-tech society. Creative politicians today could be more effective by helping corporations, schools, and other institutions develop a human form of enterprise that draws on America’s democratic heritage. One striking possibility is to form a Democratic “Contract with America.” Where the Republicans gained power by seizing the iron need to decentralize, the Democrats could gain power by ensuring the iron need for responsible local governance. Governments could offer corporations and other institutions freedom from regulations and taxes—if they adopt democratic governance systems that assume responsibility for their social impacts.41

If a decentralized society is to work, this type of sound local governance will be needed to create self-regulating, vibrant communities that replace federal controls and welfare programs.

A Global Race to Invent the Economy of the Future

This chapter has defined the following major dilemma and how managers can best operate in the new global order:

1. Although the world is moving toward unification, the emerging global economy is increasingly characterized by widespread disintegration of corporations and governments.

2. This decentralization is causing a serious dilemma between capitalism and community, although each nation may experience it differently.

3. Managers have an opportunity to create a new form of political economy that draws its strength from creating pockets of entrepreneurial community at the grassroots level.

Events will not evolve this neatly, since a race is under way to discover the secrets of success for a new economic era that nobody really understands. It almost seems as though the globe has become a great laboratory in which competing nations and corporations must work feverishly to invent new economic prototypes for the future before disaster strikes.

If Russians and Americans are unable to meet this challenge, Germany, Japan, and China seem most likely to emerge as the dominant global powers. Germany is poised to become the gateway between East and West. Japan is forming alliances throughout Asia and the rest of the world. And China’s great size almost ensures it a central role in the world economy. Without major changes, the United States may become a marginal global actor that celebrates innovative freedom and extravagance, albeit accompanied by increasing poverty, crime, and other social problems. Russia would probably sink further into its present quagmire of outlaw capitalism, unworkable bureaucracy, and poor living standards, punctuated by periodic social revolts that are brutally suppressed.

But I am more impressed by the imperatives of information technology which are now forming a new global order. Something similar to Democratic Enterprise seems inevitable for the same reason today’s economy replaced the feudal system two hundred years ago: not because of good intentions, altruism, or even sound planning, but because a more productive blend of markets and democracy is now essential to meet the demands of an Information Age. The inexorable logic of this historic development is likely to prevail over the next ten to twenty years, and the big question is who will provide the leadership for moving in this direction?

Capitalism and socialism suffer severe disadvantages because of structural limits in both systems: economic freedom is productive but socially disruptive, while government controls are orderly but economically stifling. It seems to me that the next great step in human progress is the transformation of these two fading ideologies into modern equivalents that can integrate social and economic values. And a seminal new idea is emerging that may finally resolve this nagging old dilemma. Managers around the globe are redefining the very nature of enterprise to incorporate social values democratically at the grassroots level.

Notes

1. See the special issue of Futures, The Global Economy, edited by William E. Halal (December 1989).

2. C. Fred Bergsten, “Clinton Makes the Pacific Connection,” Washington Post (November 13, 1994). John Goshko and Peter Behr, “Leaders of Western Hemisphere Agree to Form Free Trade Zone,” Washington Post (December 11, 1994). Akio Morita, “Toward a New World Economic Order,” Atlantic Monthly (June 1993).

3. See Heidi Vernon-Wortzel and Lawrence Wortzel, Global Strategic Management (New York: Wiley, 1992), and the special issue on global strategy published by Strategic Management (Summer 1991).

4. Emily Thornton, “Japan’s Struggle to Restructure,” Fortune (June 28, 1993).

5. Robert Ozaki, Human Capitalism: The Japanese System as a World Model (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1991). For a good analysis of differences in market systems, see “The Many Faces of Free Enterprise,” BusinessWeek (January 24, 1994).

6. Peter Gumbel, “East Germans Can’t Shed Communism,” Wall Street Journal (September 29, 1994). Jane Mayer, “Many East Germans Find There Is No Place Like Home,” Wall Street Journal (December 8, 1989).

7. Steve Liesman, “More Russians Enter Middle Class,” Wall Street Journal (June 7, 1995).

8. Peter Reddaway, “Next From Russia: Shock Therapy Collapse,” Washington Post (July 12, 1992).

9. Fred Hiatt, “Historic Chance to Aid Russia Said to Be Slipping Away,” Washington Post (March 1, 1993).

10. The president of ABB Russia said: “In another five years young Russians will have the same work habits as the West,” and the Russian government claims that real incomes rose 11 percent in 1994. But there are doubts about the validity of these statistics. See “In Poland, Reform Brings Painful Progress,” Washington Post (September 6, 1993), and “Russia’s Strivers,” BusinessWeek (1994, special issue).

11. Hobart Rowen, “Soviet Iceberg,” Washington Post (May 21, 1992). Soros is quoted in BusinessWeek (October 3, 1994), p. 105.

12. Guy Gugliotta, “Index of Social Health,” Washington Post (October 25, 1994).

13. The headline is from Business Week (November 14, 1994), p. 108. For an analysis of this conflict between business and society, see “We’re No. 1, And It Hurts,” Time (October 24, 1994). The editorial page of BusinessWeek (April 26, 1993) notes that average CEO pay rose 56 percent from the previous year to $3.8 million; the editorial concluded: “CEO pay continues to climb to ridiculous heights.… The disparity tears at the social fabric.”

14. An authoritative analysis is provided by Gary Burtless and Timothy Smeeding, “America’s Tide: Lifting the Yachts, Swamping the Rowboats,” Washington Post (June 25, 1995).

15. Lawrence Franko, “Global Corporate Competition,” Business Horizons (November-December 1991).

16. Michael Dobbs, “Who Won the War?” Washington Post (May 7, 1995); Judy Shelton, “A Flat Tax for a Strong Dollar,” Washington Post (September 6, 1995).

17. Based on a Gallup Poll conducted for The Daily Telegraph (April 1989).

18. See Amitai Etzioni, The Moral Dimension: Toward a New Economics (New York: Free Press, 1988).

19. Charles Maier, “The Collapse of Communism” (Working paper, Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 1994).

20. See Clark Kerr, The Future of Industrial Societies (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983).

21. “Europe Faces Pressure to Cut Social Spending,” Wall Street Journal (May 8, 1995). Rick Atkinson, “German Workers Getting Stiff Shot of Reality,” Washington Post (February 22, 1994).

22. Ichiro Ozawa, Blueprint for a New Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1994).

23. Herbert Henzler, “The New Era of Eurocapitalism,” Harvard Business Review (July-August 1992). Brenyon Schlender, “Japan: Is It Changing for Good?” Fortune (June 13, 1994).

24. Walesa’s statement is from Newsweek (November 27, 1989), p. 35. A good account of the role of television in bringing about the fall of the East German Communist government is provided by Tara Sonenshine, “The Revolution Has Been Televised,” Washington Post (October 2, 1990). Alexander King and Bertrand Schneider, The First Global Revolution (New York: Pantheon, 1991).

25. As noted by John Naisbitt, Global Paradox (New York: Morrow, 1994), p. 14.

26. Robert Andrews, “Democrats: Change or Die,” Washington Post (November 10, 1994). Also see John Fund, “The Revolution of 1994,” Washington Post (October 19, 1994).

27. “America’s Heartland: The Midwest’s New Role in the Global Economy,” BusinessWeek (July 11, 1994).

28. David Broader, “The Power of Our Discontent,” Washington Post (September 6, 1995).

29. Michael Porter, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: Free Press, 1990).

30. David Vise, “Comeback on Lake Erie,” Washington Post (November 11, 1994).

31. See William E. Halal, “Political Economy in an Information Age,” in Lee Preston (ed.), Research in Corporate Social Policy and Performance (Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press, 1988).

32. Samuel Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations,” Foreign Affairs (Summer 1993).

33. Herbert Henzler, “New Era of Eurocapitalism.”

34. See the special issue of BusinessWeek, 21st Century Capitalism (1994), and Joel Kurtzman, The Death of Money (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), which describe the effects of today’s $200 trillion volume of annual trade in global finance markets, which is roughly ten times the entire output of the world’s economies.

35. “Japanese Fusion,” in the special 1994 issue of BusinessWeek, 21st Century Capitalism.

36. “Soviets Reject U.S. Style Capitalism,” Washington Post (July 26, 1991). “Prague’s Progress” Wall Street Journal (July 6, 1994). “Poles Split in Vote for Parliament,” Washington Post (October 28, 1991). Lena Sun, “China’s Party Sees Threat from the West,” Washington Post (November 12, 1991).

37. The rationale for a socially oriented form of market economy was first described by Oskar Lange in On the Economic Theory of Socialism (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), pp. 57–143, and Pat Devine in Democracy and Economic Planning (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1988).

38. Reported in Washington Post (November 12, 1995).

39. John Bradford, “The Prospects for Change in the Soviet Economy” (Unpublished research report, George Washington University, 1990). Zhihua Chen, “The New China: Capitalism or Market Socialism?” (Unpublished research report, George Washington University, 1991).

40. Herbert Stein, “The Show Is Over,” Wall Street Journal (October 25, 1994)

41. Robert Kuttner, “Good Corporate Citizens,” Washington Post (August 23, 1995).