2

From Hierarchy to Enterprise

Internal Markets Are the New Form

of Organization Structure

It has become a cliché to note that business schools are notorious for their poor management. Mine was no exception. An especially irksome problem was getting the copy center to work properly. Professors thrive on paper, yet we couldn’t seem to get copies made in less than a week. We knew that our local Kinko’s could get them done in a day, but we would have to pay. Since the copy center was free, we kept using it despite bad service. In fact, that’s one reason why the service was bad: we overused this free good, clogging the system. Repeated attempts to get the copy center to improve its operations and the faculty to curb their excessive usage had little effect.

The problem was that we were relying on a hierarchical assignment of tasks that were too complex for this approach. We needed good service. We needed faculty accountability. We needed a copy center manager who was motivated to help us. We needed a choice of providers. In short, we needed a market.

After much argument, we asked the copy center manager (let’s call him Art) if he would like to turn the operation into “his own business.” He could still use the school’s copiers and facilities to serve the faculty’s needs, but his income would be based on a percentage of the profits. The faculty would get his budget and could use it to either patronize Art or other copy centers. Art had an entrepreneurial streak, so he welcomed the opportunity.

Note: Earlier versions of this chapter appeared in my publications Internal Markets: Bringing the Power of Free Enterprise Inside Your Organization (New York: Wiley, 1993), The New Portable MBA (Wiley, 1994), and The Academy of Management Executive (November 1994).

Well, everything changed within days. A few people went to Kinko’s, which got Art thinking about how to improve operations. And having to pay now, the faculty carefully considered whether they really needed fifty copies of their latest tome. Our copy center’s service soon matched Kinko’s, Art became a celebrated hero, and the problem was solved—by an internal market.

This little story illustrates that the most fundamental problem in management today is the bureaucracy that results almost invariably from large hierarchies. The hierarchical model of organization built civilization, from the pyramids of ancient Egypt, to the medieval church, to modern industry. It continued to dominate the Industrial Age because it was good at managing routine tasks performed by uneducated workers.

But the Information Age is releasing such revolutionary forces that the world is becoming an incomprehensible maze, thereby rendering today’s hierarchies obsolete.1 When Max Weber first defined the “theory of bureaucracy” based on principles of hierarchy at the start of the Industrial Age, the concept promised a Utopia of efficiency and order. Today the most damning thing one can say about an organization is to call it a “bureaucracy.” Some hierarchy will always be needed because the universe is naturally organized in a hierarchical fashion. But the former management system in which decisions flowed from the top down is now history.

This chapter shows how today’s wave of restructuring within “electronic organizations” is leading to an organic network of self-managed internal enterprises that operates more like an intelligent market system. We first examine the limitations of present approaches to restructuring and the evolution of market organizations. Then, principles for creating internal markets are described using examples of progressive companies. We conclude by exploring the implications of this profound shift from hierarchy to enterprise that makes up one-half of the new management foundation.

RISE OF THE ENTREPRENEURIAL ORGANIZATION

Today’s exploding complexity challenges our most basic assumptions about management. Hierarchy is too cumbersome under these conditions, so modern economies require organic systems composed of numerous small, self-guiding enterprises that can adapt to their local environment more easily by operating from the bottom up.2 Gerhard Schulmeyer, CEO of Siemens, put it best: “It’s not important anymore to be big … but to be fast and innovative.”3

Limits of Downsizing, Reengineering, and Networks

Companies have been moving in this direction with a vengeance as competition drives lower costs and faster innovation, as powerful new information systems automate jobs and streamline operations, and business processes are reengineered into cross-functional teams. These changes allowed CEOs to eliminate roughly one-third of their employees and layers of management during the past few years, producing flat, decentralized organizations. The pressure to downsize is so strong that it has become a way of life, even when profits are up. The chairman of Procter & Gamble said, “Our competitors are getting leaner and quicker, so we have to run faster,” while a Xerox manager added: “I know it sounds heartless when the company’s making money, but it’s the new reality.”4

This same imperative is being felt abroad. In Japan, the traditional system of lifetime employment is passing as Japanese corporations reduce management levels, lay off workers, and introduce merit pay. Here’s how a Japanese manager saw the change: “The era of waving the company flag to motivate people is over.”5

Considering the enormous impact of these difficult changes, we should not be surprised that restructuring has become very controversial. A 1995 survey of 1,800 CEOs showed that 94 percent of companies had implemented various forms of restructuring, but the economic gains have proven meager. Roughly two-thirds of these programs have failed to improve productivity or reduce costs. In addition, ten million Americans lost their jobs during the past decade, forcing U.S. wages down to the point where European and Japanese companies now open plants in the United States to take advantage of America’s cheap labor. In organizations across the land, employees have become traumatized by the fear of layoffs and are overstressed from doing the work of others. CEOs themselves know this is a problem. “If you keep [downsizing], you destroy morale and paralyze the organization,” said the CEO of Scott Paper. Jim Stanford, CEO of Petro-Canada, put it best: “You can’t shrink to greatness.”6

How did intelligent, well-meaning people get into such a mess? These are genuine attempts to create high-performing organizations to survive a complex global economy. But present restructuring is ineffective because it is largely an extension of the hierarchical system. Most restructuring is arbitrary because it originates from senior managers who are often out of touch with operations, slashing the staffs of good and poor units alike, and it is forced on unwilling people who have little interest in its success. The predictable result is that the disadvantages of hierarchy remain, while managers feel confused and guilty for laying off their co-workers—at the very time they are also urged to empower people and to collaborate. Here’s how one manager experienced it: “This year, I had to downsize my area by 25 percent. It’s emotionally draining. I find myself not wanting to go to work because I’ll have to push my people to do more. But they’re not going to complain because they don’t want to be the next 25 percent.”7

The most feasible successor to the hierarchy currently is the concept of “organizational networks.” In this model, temporary teams use groupware to form strategic alliances, producing a fluid network that can mobilize to meet changing market needs quickly.8 But the concept does not go far enough.

The network model is a good description of how organizations should look, but it does not tell us how they should work in economic terms. How do we know whether teams create value or destroy it? How much freedom is allowed? How is accountability ensured? How are resources allocated? Who has the authority to make decisions? If the answers to these questions come from top management, we once again incur the disadvantages of hierarchy. After all, GM was awash in powerful alliances even as it floundered in bureaucracy. If teams are just allowed to be “flexible,” what prevents anarchy? The Internet is a great network, but it is hardly a well-managed system.

Other metaphors that purport to replace the hierarchy suffer from the same limitation. There is the “federal” system of loosely connected units, the “pizza” or “circular” organization, the “horizontal” workplace, the “boundaryless” corporation, the “intelligent” or “learning” organization, fleet-footed “gazelles,” the “agile” company, the “starburst,” “spider’s web,” “fishnet,” and so on. In the absence of sound answers to the questions about values, accountability, and authority raised earlier, however, these remain fluid variations of hierarchy rather than true bottom-up systems. The issue remains: how can any organization be managed without impairing local autonomy?

Fundamentally, this problem will resist solution as long as we instinctively continue to think of management within a hierarchical framework. Major corporations comprise economic systems that are as large and complex as national economies, yet they are commonly viewed as “firms” to be managed by executives who move resources about like a portfolio of investments, form global strategies, restructure the organization, and set financial targets. How does this differ from the central planning that failed in the Communist bloc? Why would such control be bad for a national economy but good for a corporate economy? Can any fixed structure remain useful for long in a world of constant change?

The Internal Market Perspective

For years a dramatically different concept has been quietly emerging that realizes the ideal of bottom-up systems.

Figure 2.1 illustrates the evolution of organizational structure from the hierarchy, to the matrix, and now to networks of decentralized, entreprenuerial units. Today, progressive organizations have become clusters of small business units that behave as separate firms in their own right. Some global corporations, such as Asea Brown Bovari (ABB), have thousands of such profit centers with their own products, clients, and competitors. At times they may buy and sell to other units within the parent corporation, compete with one another, and even work with outside competitors. The same trend can be seen in efforts to reinvent government; for instance, the concept of parental “choice” is gaining acceptance in education to force schools to compete for students.9

These structures cannot be explained with hierarchical concepts, and so an entrepreneurial economic framework has been proposed by Jay Forrester, Russell Ackoff, Gifford and Elizabeth Pinchot, and myself that views organizations as markets—“internal markets.”10 Just as the post-Communist bloc is adopting markets, so too are large corporations. Tom Peters urged: “Force the market into every nook and cranny of the firm.”

FIGURE 2.1. THE EVOLUTION OF ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE.

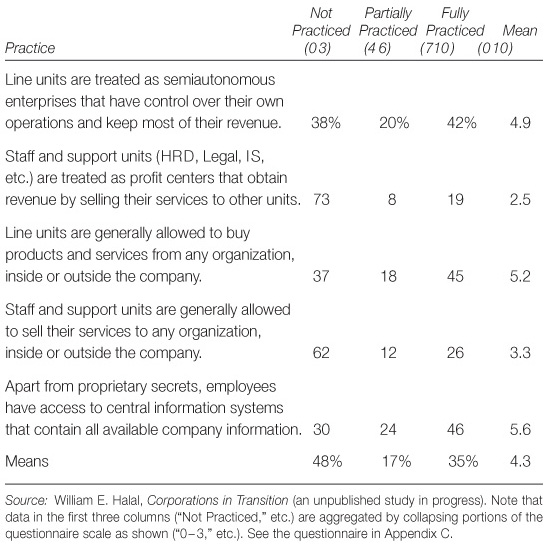

As shown in Box 2.1, internal markets are metastructures, or processes, that transcend ordinary structures. Unlike fixed hierarchies or centrally coordinated networks, they are complete internal market economies designed to produce continual, rapid structural change, just as external markets do. Although only a few companies have implemented this idea as yet, Table 2.1 shows fairly wide acceptance of some key features, and the examples in Box 2.2 demonstrate various approaches that have been used.

People are initially skeptical about internal markets because the idea breaks so sharply from the hierarchy. At first the notion seems fraught with conflict, and it is certainly true that internal markets incur the same risks, turmoil, and other drawbacks of any market system. But these doubts occur precisely because the concept represents a dramatically different form of logic. Once we grasp the central idea that an internal market replicates an external market, the behavior of such a system becomes almost self-evident.

As hierarchical controls are replaced by market forces, the release of entrepreneurial energy produces roughly the same self-organizing, creative interplay that makes external markets so advantageous. Experience shows that solutions to difficult problems emerge far more quickly and almost spontaneously, permitting a rush of economic growth that can rarely be planned by even the most brilliant managers of hierarchical systems.

Markets can be chaotic, but they are spreading around the globe because they excel over the other alternative—central planning—whether in communist governments or capitalist corporations. In both nations and organizations, planned economies are too cumbersome to cope with a complex new era, while free enterprise—either internal or external—offers an economic philosophy able to produce adaptive change rapidly and efficiently.

PRINCIPLES OF INTERNAL MARKETS

The three central principles shown in Box 2.1 are described below more fully, illustrated by the experiences of companies my colleagues and I have studied and worked with.

Transform the Hierarchy into Internal Enterprise Units

Rather than think of units as “divisions,” “departments,” and other hierarchical concepts, the logic of internal markets transforms line, staff, and all other units into their entrepreneurial equivalents—an “internal enterprise,” or what the Pinchots call an “intraprise.” This change may require creative reengineering of existing structures, but it is usually feasible if an external or internal client can be identified, and that is almost always possible, as we will show. An AT&T manager told me: “We link internal suppliers with internal and external customers.”

Units are converted into intraprises by accepting controls on performance in return for freedom of operations. Hewlett-Packard is famous for its entrepreneurial system, which holds units accountable for results but gives them wide operating latitude. As one HP executive described it, “The financial controls are very tight, what is loose is how [people] meet those goals.” This sharply focused understanding enhances both control and freedom to provide two major strengths:

1. All units are accountable for results.

2. Creative entrepreneurship is encouraged.

There is wide agreement that performance should be evaluated using customer satisfaction, product quality, and other measures to ensure a realistic balance that avoids overemphasizing short-term profit. Managers are then held accountable through incentive pay, stock plans, budget allocations, or outright dismissal. The ideal arrangement is to treat each unit as a small, separate company, free to manage its own operations and resources. It is important to allow all units the freedom to conduct business transactions both inside and outside the firm. Without that freedom, managers are subject to the bureaucracy of central controls, about the same way the Soviets overcontrolled their economy.

Although the decentralization of line units is well known, Box 2.3 shows how the concept is being applied to staff units, manufacturing facilities, information system (IS) departments, research and development (R&D), marketing and distribution, employee work teams, starting new ventures, government, and even the CEO’s office. This reminds us of the key principle for creating internal markets: all market functions should ideally be replicated within organizations. Raymond Smith, CEO of Bell Atlantic, described the logic:

We are determined to revolutionize staff support, to convert a bureaucratic roadblock into an entrepreneurial force. Staffs tend to grow and produce services that may be neither wanted nor required. I decided to place the control of discretionary staff in the hands of those who were paying for them … line units.… The most important thing is that spending for support activities is now controlled by clients.11

Figure 2.2 illustrates the internal market that results from “privatizing” an organization with product, functional, and geographic structures. The heart of the system consists of new ventures spun off by product divisions to become independent business units that develop products or services. Functional support units are profit centers that sell their assistance to other units or external businesses. Geographic areas are also profit centers, distributing the full line of products and services to clients in their region. The network of business relationships formed by the intersection of these product, functional, and regional units constitutes the internal market economy.

From this view, the organization is no longer a pyramid of power but a web of changing business relationships held together by clusters of internal enterprise—as in any market. This system may appear radically different, but it simply represents an extension of the trend that began decades ago when large corporations decentralized into autonomous product divisions.

Create an Economic Infrastructure to Guide Decisions

With operational matters relegated to internal enterprises, executives focus on designing an infrastructure of performance measures, financial incentives, communication systems, an entrepreneurial culture, and other corporatewide frameworks. This infrastucture then allows market forces to guide decisions instead of relying on administrative fiat. The behavior of this market system is then regulated, monitored for weaknesses and failures, and corrective changes are made to improve its performance.

FIGURE 2.2. EXAMPLE OF AN INTERNAL MARKET ORGANIZATION.

When Alcoa moved to an internal market economy, its managers soon realized that decisions previously had been based on faulty estimates of costs and revenues. Like many corporations, the finances of operating units were pooled into larger divisions, absorbed by corporate overhead, and otherwise not identified accurately for individual units. Upon converting all units into autonomous enterprises with their own profit and loss statements, the newfound awareness of actual costs and revenues immediately altered decisions in more realistic directions. AT&T realized the same benefits when its large groups were divided into forty or so profit centers to highlight their individual performance. “The effect was staggering,” said James Meehan, the CFO.

A striking example of the power of incentives to change behavior can be seen when converting staff units into profit centers. In the typical organization, IS services are provided free to line units, with the predictable result that people waste resources carelessly. Stories abound of line units demanding multiple copies of huge computer printouts that are never read, of overseas offices equipped with international phones lines used by clerks to call home every day. But when presented with monthly bills by the IS department, there is a marked change in attitude, causing line managers to select less costly systems that often provide better service as well.12 Conversely, giving line units the freedom to choose among competing IS sources causes these internal suppliers to shape up equally fast.

There is also a need to instill the subtle norms of a social system. MCI has learned that an internal market must be augmented by an entrepreneurial culture that stresses taking initiative, embracing change, and supporting employees. The MCI culture constitutes a commonly understood, informal management system that guides human behavior effectively. Since this system exists in the minds of people rather than in cumbersome written policies, it is far more flexible because it is a shared idea. MCI employees and the company are one and the same, allowing quick agreement on a new product, organizational change, and other complex undertakings.

The impact of these various aspects of infrastructure illustrates the crucial need to design organizations as complex, interacting systems. As Jay Forrester and Peter Senge point out, managers today must become organizational designers, in addition to operators, by creating a new class of adaptive, high-performing, intelligent organizations.13

Provide Leadership to Foster Collaborative Synergy

This model of entrepreneurial management raises tough questions about the role of executives and the very nature of corporations. If an organization is no longer a fixed, centrally controlled structure, but a fluid tangle of autonomous units going their own way, what gives it an identity that makes it more than the sum of its parts? What is best for the individual units and for the organization as a whole? How does this array of business units differ from an ordinary market economy? Why should they remain together at all? In short, what truly is a modern corporation, and how should it be managed?

CEOs may give up much of their formal authority in a market system, but they lead by ensuring accountability, resolving conflict, encouraging cooperation, forming alliances, providing inspiration, and other forms of strategic guidance that shape this system into a more productive community. One of Hewlett-Packard’s great strengths is that its executives guide by persuasive leadership rather than fiat. The CEO, Lewis Platt, said, “In HP, you really can’t order people to do anything. My job is to encourage people to work together, to experiment.”14

MCI provides a good example in which corporate executives work hard to turn contentious issues into advantageous solutions. Top management understands that the autonomy of operating managers must remain inviolate, so executives avoid imposing decisions. Yet the company’s entrepreneurial stance often provokes heated controversy over risky ventures. A new product concept, like MCI’s Friends & Family, may be proposed by sales, engineering, or any other group, and is then the subject of a debate over the merits of the idea. Rather than squelch this conflict, MCI executives embrace it as a stimulant for tough, creative argument. By providing an acceptable form of constructive exchange among diverse viewpoints, a solid course of action usually emerges that all can support with confidence.

Johnson & Johnson (J&J) encourages coalitions of business units that serve everyone better. J&J’s 166 separate companies retain their fierce autonomy because it “provides a sense of ownership that you simply cannot get any other way,” says the CEO, Ralph Larsen. But the company’s big clients, Wal-Mart, Kmart, and other retailers, want to avoid being bombarded by sales calls from dozens of J&J units. The CEO’s solution was to urge his operating managers to pool such efforts into “customer support centers” that operate as internal distributorships to coordinate sales, logistics, and service for each major retailer.

These examples illustrate the resolution of two opposing sets of difficult demands. Modern executives must permit operating managers entrepreneurial freedom to gain their commitment, creativity, and flexibility. Yet they must also avoid disruptive conflict, needless duplication, and unnecessary risk. A market can provide this combination of freedom and control, but not by remaining a laissez-faire system. Leadership is essential to reconcile these opposing demands into a synergistic corporate community that adds net value to its internal enterprises.

Indeed, without the creation of net value there is little to justify uniting business units into a larger parent organization. The breakup of AT&T into three separate companies during 1995 illustrates a lack of this synergy. Hierarchical organizations may contain units that destroy value, but this is not apparent because the internal economic behavior of the system is masked by its bureaucratic structure. An internal market strips away the bureaucracy by regarding each unit as an enterprise, setting the stage for more realistic management.

Thus, an internal market is not simply a laissez-faire economy, but a guided economy, a vehicle for reaching common goals that is more effective than either a laissez-faire market or an authoritarian hierarchy. As these principles show, corporate executives guide an internal market by designing an economic infrastructure, setting policies to regulate the system, resolving critical issues, sharing valuable knowledge, and encouraging cooperative strategies. These benefits create the synergy that adds value which outside enterprises cannot match working alone.

THE FLOWERING OF ENTERPRISE

Surveying the evolution of organizational structure, the move from hierarchy to enterprise constitutes one of the most profound changes in management. The old pyramid has now become a decentralized network of semiautonomous units loosely coordinated by vestiges of the old chain of command. I estimate that the development of complete internal market systems is likely to form the next major phase in this process, entering the mainstream over the next decade or so as the Information Age matures.

If this estimate holds, the idea of hierarchy may soon seem as archaic as the divine right of kings. Most organizations will then be self-organizing clusters of roaming intrapreneurs who work together over communication networks, creating a seamless global economy in which power, initiative, and control flow from the bottom up—the flowering of enterprise.

Note that a market structure does not ensure effective management, but it is an essential starting point. Talented people, inspiring leadership, clever strategy, and other factors are also necessary, of course. But these are secondary causes. The Russians are highly educated, talented people with a wealth of resources, yet their economy was trapped in an archaic system for decades.

A similar problem faces managers in capitalist societies today. Capable, well-intentioned people working in corporations, governments, and other institutions are trapped in outmoded hierarchical structures. This impending shift to a market form of organization presents roughly the same challenges and opportunities posed by the restructuring of socialist economies. What are the implications of this profoundly different philosophy?

The Advantages and Disadvantages

Naturally, internal markets incur the same disorder, risk, and general turmoil of external markets, but they also permit some compelling advantages. As shown in Table 2.2, the organization’s environment determines which approach is best, which then fixes the type of accountability, motivational system, and culture needed, as well as the corresponding advantages and disadvantages.

Economists argue that hierarchies are superior because markets produce transaction costs in searching for alternatives, managing financial transactions, and so on. But the Information Revolution is reducing transaction costs, and any cost increases can be offset by decreased overhead and gains in innovation. Western Airlines eliminated five hundred management jobs, and the resulting decrease in bureaucracy saved huge costs and improved performance. Studies by Thomas Malone at MIT show that decreasing information technology costs “should lead to a shift from [management] decisions … to the use of markets.”15

Many think that markets increase conflict as units pursue different goals and compete for resources. My experience shows that market systems can resolve the abundant conflict that persists now. Peter Drucker observed that conflict within corporations is more intense than conflict between corporations, largely because decisions are often imposed arbitrarily and the choices are minimal, if any; so relations are usually fraught with tension and misunderstanding. In a market, however, decisions are clearly defined, voluntary, and selected from a range of options, providing a rational basis for sound working relationships that can replace office politics with openly reached agreements.

Even the troublesome aspects of internal markets can actually represent useful organizational adjustments. Is a manager in a free market organization unable to staff his unit? In the outside world this means that working conditions are poor. Are some units suffering losses? A market would let them fail because they do not produce value. Do differences in income exist? Wage inequalities can motivate good performance, and they urge poor workers to shape up. Thus, what appears to be disorder in a market is often vital information about economic reality that should be heeded.

Although markets are superior under most conditions today, it is important to emphasize that there are no perfect organizational designs, and there are infinite ways to organize a market system. As Table 2.2 suggests, the creative destruction of markets may unleash reservoirs of energy, but this energy can turn into anarchy if not guided into useful paths. Conversely, hierarchical control may avoid this disorder, but it also inhibits creative freedom.

We should hold no illusion that some universal structure can be applied in an all-encompassing way. Internal markets are no panacea. They are not useful in military operations, space launches, and other situations requiring close coordination of thousands of people and intricate plans, nor in routine operations facing a relatively simple, stable environment.

The “Organization Exercise” in Appendix A can help managers experience these differences. When conducting two sets of tasks of varying complexity, groups almost invariably develop a hierarchical structure for the simple task and a network structure for the complex task. You can thereby vividly appreciate the reasons for these two different structures and how they would work and feel.

Thus, organizations will have to trade off the costs and gains of each approach. The prudent executive will combine varying degrees of hierarchical control and market freedom to find the mix that best suits his or her organization.

Living with Market Systems

The drawbacks of enterprise seem especially severe now as mergers, bankruptcies, layoffs, and other changes are increasing unemployment, ending corporate loyalty, and generally making work life more traumatic. If internal markets introduce more of the same, how will we tolerate working in market organizations?

These turbulent changes are unavoidable because the world is in the throes of massive economic restructuring that exerts two major demands: accountability for performance in order to survive, and creative entrepreneurship to adapt to chaotic change—the two major strengths of internal markets. This explains the new role now emerging for individuals in a fast-moving, temporary society. Whereas it made sense for people to function as employees in a hierarchical economy, an internal market system requires people to assume the role of entrepreneurs.

Thus, the former paternalistic employment relationship in which people were paid for holding a position is yielding to a “self-employed” role in which people are offered an opportunity. The old “work ethic” is becoming an “enterprise ethic” that values the freedom and self-reliance, as well as the rewards and risks, that form the complementary rights and responsibilities of entrepreneurship (as we will see in Chapter 6). In fact, these are the roles preferred by the majority of businesspeople today.16

If organizations can make this adjustment, we may find that an internal market is less harsh. By decentralizing responsibility to small, self-managed units, the demands of a turbulent economy could be better resolved through voluntary layoffs, growing the business, tolerating lower rewards, or other local solutions. Self-management thereby permits constant, small adjustments to the ebb and flow of market forces, avoiding the large periodic crashes that now result from having executives bear this unreasonable burden alone.

For instance, a market organization can help make downsizing, reengineering, and other forms of restructuring more successful. Just as any external business can manage its affairs better without government interference, these approaches are likely to work best if they originate voluntarily from autonomous units that are accountable for serving their clients. Managers who treat units as internal enterprises will almost invariably improve operations beyond their expectations. Ralph Larsen, CEO of J&J, says: “Managers come up with better solutions and set tougher standards for themselves than I would impose.”17 In place of forced downsizing, then, this bottom-up approach produces self-initiated rightsizing throughout the organization—“self-sizing.”

Likewise, studies show that two-thirds of TQM programs fail because they are imposed from the top down.18 The principles of TQM are valuable, but they are not likely to be effective without first creating a keen sense of responsibility for some team to serve its clients—again, an internal enterprise. There is simply no substitute for the dedication, ingenuity, and, yes, even the mad zealotry of entrepreneurs committed to their business.

Finally, markets can help manage organizational networks. In a hierarchical structure, top managers control alliances to ensure that they are economically sound, but this is time-consuming and undermines operating managers. In a market organization, however, unit managers handle alliances because that is the way everyday relationships are managed. For instance, Corning, one of the leading companies in forming alliances, currently has fifty or so joint ventures among its semiautonomous product divisions, foreign subsidiaries, and business partners around the world.19

Corporate executives may provide advice and support, but they could not possibly control the explosion of networking that lies ahead. A proliferation of R&D consortia, supplier-manufacturer-distributor linkages, networking among “virtual” corporations, joint ventures among competitors, and business-government partnerships are rapidly connecting all corporations, governments, and universities together in a dense social infrastructure, as depicted on the cover of this book.20 Internal markets will facilitate the operation of this global network.

The most useful role for top management is to form a collaborative corporate community that helps ameliorate the turmoil of a turbulent world, as we will see in the next chapter. It would also be useful to develop a working environment hospitable to creative people, emulating the hundreds of business incubators that have sprung up to nurture new ventures. One of IBM’s most successful actions was the Independent Business Unit concept that created the PC in a year and a half. GM’s new electric car project is spearheaded by an autonomous team of two hundred people.

Our views may change as organizations evolve, but internal market systems seem the logical conclusion of current restructuring efforts. By designing organizations as self-managed clusters of internal enterprises, downsizing, reengineering, TQM, networks, and other restructuring practices are likely to become more effective.

Corporate Perestroika

The major conclusions about organizational structure presented in this chapter can be summarized as follows:

1. As economies become more complex, they must be managed by “organic” systems operating from the bottom up.

2. Present restructuring concepts are limited because they are largely modifications of the top-down hierarchy.

3. A different perspective based on principles of enterprise is evolving to create complete “internal market economies” that are designed and managed roughly like “external market economies.”

4. Internal markets are not appropriate in all cases, but they are best for most organizations today because they offer the dynamic qualities needed to navigate a complex world.

Transforming organizations into market systems is formidable because it involves a profound social upheaval; it could be thought of as “Corporate Perestroika,” somewhat like the struggle facing the post-socialistic bloc. Experiences of companies that have made this transition offer some guidelines, as shown in Box 2.4. The CEO described how ABB created the system described in Box 2.5: “We took our best people and gave them six weeks to design the restructuring. We called it the Manhattan Project.”21

Many other corporations are moving in this same direction. In the late 1980s when computer companies had become bloated, Hewlett-Packard restructured to avoid the bureaucracy that swamped IBM (see Box 2.6). “We had too damn many committees. If we didn’t fix things, we’d be in the same shape as IBM is today,” said David Packard. HP dismantled unneeded controls to renew its belief that each division should be a self-managed enterprise. Former CEO John Young endorsed the development of radical new products—such as HP’s first desktop printer that competed with the company’s existing products—which would have been heresy at IBM. Today the LaserJet line accounts for 40 percent of HP’s sales. HP was valued at one-tenth of IBM in 1990; through this skillful blend of enterprise and support, HP is now worth roughly as much as IBM.

Although corporations are using market mechanisms, managers do not yet generally understand the broader concept of an internal market economy. Table 2.1 shows that most corporations do not allow profit centers adequate freedom, they impose limits on outsourcing, and their support units are rarely profit centers. The result is that, throughout large companies, business units strain against corporate bureaucracies that burden operations with excessive overhead and monopoly power.22 Managers in the CIT survey reported: “We can’t use outside sources if a product or service is available inside,” and “I know of no company where staff units are nothing but profit drains; they are the most sacred of cows.” So there is a long way to go before we realize the potential of internal markets.

In the final analysis, a market form of organization seems almost inevitable because it offers the only way of adapting to an age of constant, rapid change. Instead of relying on the heroic but risky judgment of executives to move the organization in some wholesale direction, the units of an internal market feel their way along like the cells of a superorganism possessing a life of its own, producing a constant stream of adaptive change. To use a phrase from chaos theory, the central advantage of an internal market system is that it “creates spontaneous order out of chaos.”

The knowledge society lying dead ahead will present more complex intricacies than we can imagine, and much less control. This unpredictable nature of the modern world can be managed only by a local form of intelligence that guides average people to meet complexity where it begins—at the grass roots. Information technology will provide the communication for this system, and markets will provide the economic foundation.

Many will think this challenge is too enormous, but that is exactly what we once thought about the prospect of changing the Soviet Union. The move to market organizations seems likely to roll on because internal markets offer the same powerful advantages that inspired the overthrow of Communism: opportunities for personal achievement, liberation from authority, accountability for performance, entrepreneurial initiative, creative innovation, high quality and service, ease of handling complexity, fast reaction time, and flexibility for change. Imagine Corporate America’s creative managers, engineers, and workers being turned free to launch myriad ventures, all guided by top management teams that provide a supportive infrastructure and inspiring leadership. Yes, many of these ventures would fail, but many more would thrive to create a new breed of dynamic, self-organizing institutions.

Managers could realize all these benefits by harnessing the abundant entrepreneurial talent now languishing beneath the layers of today’s bureaucracies. The first step is to recognize that organizations must be designed and managed as market economies in their own right.

Notes

1. A summary of the changes under way is provided by William E. Halal, “Global Strategic Management in a New World Order,” Business Horizons (December 1993).

2. See Margaret Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1992).

3. “Putting the Byte Back into Siemens Nixdorf,” BusinessWeek (November 14, 1994).

4. Frank Swoboda, “The Case for Corporate Downsizing Goes Global,” Washington Post (April 9, 1995). Matt Murray, “Amid Record Profits, Companies Continue to Lay Off Employees,” Wall Street Journal (May 4, 1995).

5. “Japan, Wracked by Recession, Takes Stock of Its Methods,” Wall Street Journal (September 29, 1993).

6. Ronald Henkoff, “Getting Beyond Downsizing,” Fortune (January 10, 1994). Rahul Jacob, “TQM: More than a Dying Fad?” Fortune (October 18, 1993). Joann S. Liblin, “Don’t Stop Cutting Staff,” Wall Street Journal (September 27, 1994).

7. Reported in “Rethinking Work,” BusinessWeek (October 17, 1994).

8. The network perspective is best represented by Raymond Miles and Charles Snow, Fit, Failure, and the Hall of Fame (New York: Free Press, 1994), and Jessica Lipnack and Jeffrey Stamps, The Age of the Network (Essex Junction, Vt.: Oliver Wight/Omneo, 1994).

9. David Osborne and Ted Gaebler, Reinventing Government (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1992).

10. Jay Forrester, “A New Corporate Design,” Industrial Management Review (Fall 1965), pp. 5–17; Russell Ackoff, Creating the Corporate Future (New York: Wiley, 1981); Gifford and Elizabeth Pinchot, The End of Bureaucracy and the Rise of the Intelligent Organization (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1994); William E. Halal et al., Internal Markets: Bringing the Power of Free Enterprise INSIDE Your Organization (New York: Wiley, 1993).

11. Rosabeth Moss Kanter, “Championing Change: An Interview with Bell Atlantic’s CEO Raymond Smith,” Harvard Business Review (January-February 1991).

12. See William E. Halal, Fee-For-Service in IS Departments (A report of the International Data Corporation, 1992).

13. See Halal et al., Internal Markets, Chapters 3 and 5.

14. Alan Deutschman, “HP Continues to Grow,” Fortune (May 2, 1994).

15. See Oliver Williamson, Markets and Hierarchies (New York: Free Press, 1975). The Western example is from David Clutterback, “The Whittling Away of Middle Management,” International Management (November 1982), pp. 10–16. Thomas Malone et al., “The Logic of Electronic Markets,” Harvard Business Review (May-June 1989).

16. Paul Leinberger and Bruce Tucker, The New Individualists (New York: Harper-Collins, 1992). John Kotter, The New Rules: How to Succeed in Today’s Corporate World (New York: Free Press, 1995).

17. Brian O’Reilly, “J&J Is on a Roll,” Fortune (December 26, 1994).

18. R. Krishnan et al., “In Search of Quality Improvement,” Academy of Management Executive, 7, (4) (1993).

19. Jordan Lewis, Partnerships for Profit (New York: Free Press, 1990).

20. “Learning from Japan: How a Few U.S. Giants Are Trying to Create Home-grown Keiretsu,” BusinessWeek (January 27, 1992). Rosabeth Moss Kanter, “Pooling, Allying, and Linking Across Companies,” The Academy of Management Executive (August 1989).

21. William Taylor, “The Logic of Global Business,” Harvard Business Review (March-April 1991).

22. For a good analysis of this problem, see Craig Cantoni, Corporate Dandelions (New York: Amacom, 1993).