6

Knowledge Entrepreneurs

A Working Contract of Rights

and Responsibilities

Not long ago, work life was a pretty straightforward affair. You found a job, did what you were told, and were paid a salary.

But recently this system began coming apart. Layoffs have shattered the bonds of employee-employer loyalty. Wages have been falling for two decades. Union membership has dropped to a fraction of its former levels. And one-third of the labor force has become lost in a “contingent” status of part-time or temporary work.

At the same time, other changes have begun introducing more enlightened work practices. Employees are encouraged to participate in major decisions. Many now own their companies. They enjoy broader rights to control their work. The labor force is becoming diverse. And most jobs are far more interesting than they once were.

These crosscurrents in the employment relationship flow out of a turbulent passage in our concept of work. The paternalistic system in which “bosses” supervised “employees” in running the machinery of an Industrial Age is yielding to a complex world of knowledge work where more is asked of us. Organizations today need the intellect, involvement, and creative ideas of everyone who works in them. The confusing changes noted above are searching steps toward redefining work life.

This chapter sketches out the work roles most people will occupy in a decade or so. In a world governed by knowledge, change, and complexity, people will increasingly work in a self-directed capacity to solve intellectual problems. Most workers will be part of a self-managed team that collaborates with other teams and organizations, all operating freely over the global grid of information networks. As I outlined in Chapter 2, managers will have to organize these people into Information Age equivalents of the entrepreneur—knowledge entrepreneurs—who enjoy the freedom and rewards of being self-employed, while also bearing the responsibilities and risks that are involved.

REDEFINING THE EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP

This transition poses daunting conflicts as people are wrestled out of their old roles, but it also promises to realize the human potential that has lain dormant throughout history. For instance, knowledge workers must be treated as self-employed professionals because their work is inherently complex, innovative, and requires deep personal involvement, so it cannot be “supervised.” That’s why all professions invariably develop an ethic of self-control.

The Labor-Management Conflict Intensifies

These adjustments are not going to be made by simply “empowering people” in some vague sense. How does one “empower” 100,000 employees of a typical Fortune 500 company to join in major decisions? Can any group larger than a few hundred people reach consensus quickly enough to survive, or would it resemble the U.S. Congress? Even the famed Mondragon system of Spain suffered a breakdown as a result of growing bureaucracy.

Consider the concept of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), which is often considered the way to salvation. ESOPs are spreading through the airline industry because they offer employees pride of ownership, a partial defense against hostile takeovers, tax deductions, and other advantages. In 1985 Eastern Airlines became the first large American company to be employee-owned, and four employees gained seats on the board of directors. I vividly recall the excitement of seeing Eastern pilots, flight attendants, and ticket agents appearing in TV commercials announcing the superior service on their airline. Yet severe labor-management conflict soon led this great airline to bankruptcy.1 A worker expressed the yawning gap between promise and reality: “I worked here before [the ESOP] and I worked here afterward. I don’t see any change. Things go on exactly as before.”

This is a chronic problem in ESOPs. The evidence shows that employee ownership itself is rarely advantageous; rather, it is the self-management that ESOPs allow in small firms that is most useful. However, any system involving more than a few hundred members is simply too big for open decision-making among all concerned. A large meeting could hold everyone, but groups of more than twenty to fifty people can rarely work together well, and so a formal management hierarchy of some type is unavoidable. Also, resources are always scarce, which leads to the economic reality of making tough decisions that will not please all parties. As we saw in Chapter 3, a more fundamental problem is that employees represent but one stakeholder, so ESOPs cannot provide the broader governance needed to form a corporate community. That may explain why the pattern of employee ownership in America has been limited to a minority of stock in almost all corporations where it is used.

The list of such obstacles to a human workplace is long, usually leading ESOPs back to the very system they were designed to avoid. It will be interesting to see if the fate of Eastern Airlines is visited on the newest big ESOP, United Airlines.

Most of the other innovations in employee relations have experienced similar disappointments. Scholars such as Abraham Maslow, Douglas McGregor, and Rensis Likert demonstrated the virtues of participative management in the 1950s, yet very little changed until the 1990s, and some of this is questionable. The demoralizing effects of downsizing, TQM, and reengineering are so notorious they are usually considered to be euphemisms for “layoffs”; one of the hottest training seminars for managers in 1995 was “How to Fire Employees.”2

These problems may escalate because advanced nations such as the United States are passing through a chronically depressed phase of economic development. There are minor highs and lows, of course, caused by the normal four-year business cycle. But superimposed over these short-term oscillations is the trough of a sixty-year Kondratieff cycle that should continue throughout the 1990s. The Great Depression was caused by the previous trough that occurred in the 1930s. And global competition is intensifying as Latin America, Asia, and other developing nations that pay their workers $1 per hour take work away from modern labor forces that cost $20 per hour. Not only are jobs going to low-wage countries, their workers are coming here. Just as a global economy now allows capital to seek its highest returns around the world, poor people from Eastern Europe, China, Mexico, and other developing nations are flowing across borders searching for higher wages.3

Thus, relentless labor competition is likely to produce further economic pressures on employment. Knowledge workers may remain largely immune to these pressures because their valuable skills are in short supply. But unskilled workers who must compete in a global market for blue- and white-collar jobs will suffer increasing demands for low wages and high productivity.4

These pressures are growing at a time when workers need higher incomes. Because the cost of living has soared, surveys show that 75 percent of college students are primarily interested in “being well-off financially.”5 Little wonder when the price of a middle-class home in New York, Paris, or Tokyo starts at half a million dollars. It does not take long to discover that one cannot afford a reasonably comfortable lifestyle with an income of less than $50,000 per year.

This review of employment relations does not dispute the important progress that has been made. Employees have gained many benefits, and employers have gained increased responsibility for performance. It does, however, caution managers against letting overly optimistic intentions and unreasonable expectations turn into disappointing failures. The labor-management conflict that persisted throughout industrialization remains alive today. Both parties remain stuck in an adversarial posture because we lack an institutional system for sorting out this complex relationship.

Rise of the Knowledge Workforce

In roughly the same way the Great Depression prepared the ground for the booming service economy that flourished between the 1950s and the 1980s, today’s recession should lead to a robust knowledge economy starting during the decade of 2000–2010. The painful symptoms of economic decline—high employee turnover, low wages, and restructuring—are unfortunate preludes in the process of “creative destruction” that clears the economic landscape for this coming burst of growth.

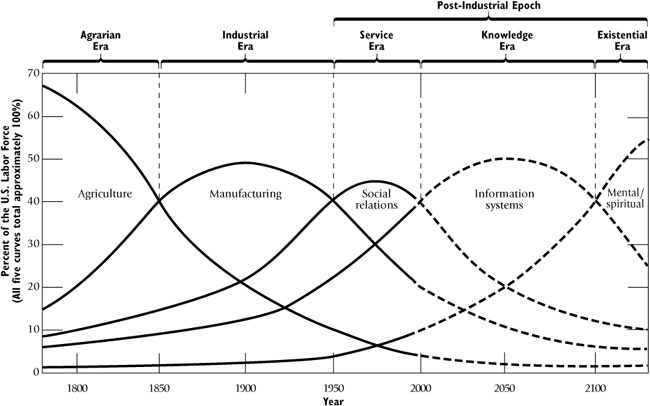

The first priority is to put the industrial past behind by automating as much routine work as possible. Many people resist automation because it eliminates jobs, and others fear technology generally. Automation is certainly traumatic, but better jobs are created by opening up new frontiers. That’s why the historic trend continually moves in this direction, as shown in Figure 6.1.

Blue-collar work has declined from its high point, when half of the labor force worked in factories, to roughly 20 percent in 1995. Automation should continue to the point where 10 percent or less of the workforce will perform blue-collar work in a decade or two, just as agriculture, which once claimed two-thirds of all workers, now employs only 3 percent of the workforce. The Service Economy began about 1950, when the number of white-collar workers first exceeded the number of blue-collar workers. As we learn to use powerful new information technologies better, office automation should also decrease the number of white-collar workers from its present 40 percent to about 20 to 30 percent over the next decade or two. The remaining 60 to 70 percent or so of the workforce may then be composed of knowledge workers: skilled manufacturing teams, information system designers, managers, professionals, educators, scientists, and the like.6

This process represents a natural cycle in economic development that is disruptive, to be sure. Nonetheless, work is slowly but inexorably moving from physical labor, to social relations, to creating knowledge, thereby boosting productivity, living standards, and the quality of life to unprecedented levels.

Some economists contend that service work is so inherently personal that it cannot be automated. But ATMs, electronic shopping, computerized communications, educational television, and other advances are proving otherwise. AT&T used computer systems to reduce its force of phone operators from 250,000 in 1956 to 50,000 today, and the number is still falling.7 Imagine the impact on universities when courses featuring “star” professors can be broadcast around the globe. As Figure 6.1 also suggests, this process should in time lead to a focus on the “mental/spiritual” domain, as we noted in Chapter 4, but that is another story.

FIGURE 6.1. THE EVOLUTION OF WORK.

PRINCIPLES OF KNOWLEDGE WORK

Naturally, knowledge work will dramatically change organizations. American business invested $1 trillion in office automation during the 1980s, but saw little gain because the technology was simply laid over outmoded organization structures. Paul Strassmann, who was chief information officer at Xerox and at the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), noted: “For thirty years America brought in computers to speed up the kind of work that just accentuates bureaucracy.”

The payoff began in the 1990s as managers learned how to redesign organizations.8 Although scholars and consultants have struggled to define the emerging principles of work, I am most impressed by the remarkable pragmatism and diversity all about us, as illustrated in Box 6.1. It is truly amazing to see, time and time again, how the myriad variations people can devise almost defy any model. Although the concepts offered here reflect the New Management themes of internal markets and corporate community, they are general guides rather than firm principles.

Use Information Systems to Create Small Self-Managed Units

The focus is on breaking large organizations down into small, self-managed units. The large manufacturing plant is giving way to small “focused factories” that produce a variety of small products or subassemblies of large products (such as autos). The same concept is breaking large white-collar organizations into small offices that provide some well-defined service. This move from economies of scale to small, autonomous units minimizes bureaucracy, encourages unit cohesion, and permits flexibility for change.

Intelligent information systems then integrate all operations into a working whole. Within factories, computer-integrated manufacturing (CIM), uses distributed networks of powerful PCs to assist all phases of work, from computer-aided product design (CAD), to manufacturing (CAM), to inventory control, to distribution. In offices, local area networks (LANs) or groupware systems are doing the same, allowing people to “telework” from any location. The result was nicely summed up by Ramchandran Jaikumar: “The behemoth is gone. The efficient factory is now an aggregation of small cells of electronically linked and controlled flexible manufacturing systems.”9

Each unit is then managed by a self-directed team of knowledge workers who are given almost total control—from product design, to manufacturing, to sales, to service, to disposal. Computerization permits such flexibility that products can be customized to suit individual needs; thus close liaison with the client initiates the manufacturing cycle by specifying product design. Suppliers and distributors can be integrated into operations using on-line computer systems to automatically move merchandise. And ecological concerns increasingly require prior planning during product design and manufacturing.

Teams are held accountable by allocating budgets, pay, bonuses, and other resources in proportion to performance, and they are then allowed to run their affairs as they think best. They typically choose their co-workers and leaders, select their operating systems and tools, and work with suppliers and other units, usually doing a better job than formally appointed supervisors. Self-directed teams are particularly good at disciplining their own members. “Sometimes we have to tell our co-workers who aren’t carrying their load that this is hurting us,” said one woman.

Although every unit should ideally be managed by a self-directed team, good teams cannot be much larger than about twenty people. Larger units may be broken down into several teams that assume responsibility for some more limited function. And, obviously, teams must coordinate their work with other teams to create a coherent, collaborative organization.

The New Employment Contract

These changes present a Herculean challenge, of course, because they require new concepts to redefine the employment relationship. Note, for instance, that there has been no mention of the traditional “job” in this discussion. In 1994, Fortune magazine announced “The End of the Job”:

The job is vanishing like a species that has outlived its time.… The conditions that created jobs—mass production and the large organization—are disappearing. [Managers] will have to rethink almost everything they do.10

Along with the move to self-managed teams, organizations are moving away from the old concept of “pay-for-position,” in which workers were traditionally paid for fulfilling specified duties: arriving at work punctually, being cooperative with others, and other behaviors covered in the typical annual performance evaluation. This system maintained a sense of orderliness, but it had little to do with productivity, and it was highly subjective. It is now being replaced by a more business-like arrangement in which employees are simply paid for the output they produce—“pay-for-performance.” Roughly three-quarters of American workplaces now use some type of “variable pay system”: incentive rates, merit bonuses, profit sharing, and other plans. “Performance pay is growing like wildfire,” said one executive.11

These trends appear to be moving toward a “new employment contract” that links employee rights with responsibilities. This is the same “participative management” that was advocated for decades, but we now see that it would be unworkable without unifying these two functions into a balanced system. If employees enjoy freedom in their work, good pay, and other rights without being accountable for results, the organization may not survive; conversely if they bear the burden of responsibilities without commensurate powers and benefits, they will be neither willing nor able to carry out their duties.

We should note that the new employment contract embodies the same logic that forms the foundation for internal market structures discussed in Chapter 2: workers are paid an agreed-upon sum for an agreed-upon result, and they are free to perform their work as they see fit. This can be thought of as an extension of an internal market system. Where internal markets concern the structure of enterprises within an organization, the employment contract concerns the structure of teams within enterprises, somewhat like an “internal labor market.”

The new employment contract offers the same advantages as do internal market systems: organizations are assured of performance, workers enjoy opportunities to earn and control their work, the system lends itself to complexity and change, and so on. But it incurs the disadvantages of market systems as well: the level of disorder is higher, there is a risk of occasional failures, and so on.

Many thoughtful people insist that work systems based on financial incentives are inherently flawed because only self-initiated work motivated by personal goals can be effective and elevating. In plain English, this view holds that money does not motivate, nor should it. This logic is appealing, but it flies in the face of common experience and the opinions of almost all business executives. The fallacy in this view comes from seeing money and higher-order interests as mutually exclusive. A wealth of research evidence shows they are both necessary.12

Motivation surveys consistently show that money alone would cause serious disenchantment with work, as the critics contend, but the surest way to devastate an organization is to not pay people equitably. The new employment contract resolves the money issue by ensuring that people are paid fairly for their contributions, and it then encourages them to channel all their talents into the creative management of their work. What more could one ask for?

Myriad variations in work practices and pay systems exist that may grow even more diverse, as the examples in Box 6.2 illustrate. Some people like incentive plans, while others prefer salaries. Some plans focus on individuals, others on teams, and still others on companywide plans; many organizations use all three levels of incentives. The difficulty of managing thousands of individual arrangements is one of the factors that make self-managed teams so attractive. Teams are also useful because they build cohesion, whereas individual pay-for-performance systems often flounder because they are seen as forcing people to compete for a limited pool of funds.

In schools, for instance, merit pay faces an uphill fight because individual performance evaluations pit teachers against their colleagues. A better solution would be to unite all teachers, administrators, and parents into a single self-managed enterprise that serves students better, thereby attracting more resources to be shared equitably among members of the team.

Whatever the pay system and the organization, the central idea is to ensure a sense of equity between the contributions each individual makes versus the rewards they receive, as noted in Chapter 3. Since equity is such a crucial but subjective matter, the optimal pay system can only be determined by the people involved. Box 6.2 shows that a wide variety of systems can be perfectly workable.

It is important to note that the concept of self-managed teams lends itself to various other arrangements, as shown in Chapter 2. Teams may be internal consultants serving internal and external clients, they can be external business groups serving internal clients, and members of teams may also be interchanged. Because teams are self-managed, they can organize their work style to include job sharing, rotation of assignments, using temporary workers, or any other arrangements they prefer. It is then an easy step to visualize an organization as a changing assembly of teams and individuals, held together by information networks, common values, and other aspects of infrastructure, thereby composing a “virtual organization.”

In such protean organizations, the challenge will be to strike a balance between the advantages of creative flexibility and the difficulty of uniting people who are working in cyberspace, as noted in Chapter 4. Both are essential, and the need for these opposing qualities is likely to grow. Tumultuous change will demand continual adaptation, yet diverse economic actors working around the globe must remain integrated into a coherent whole.

This fundamental transition to knowledge-based work is so vast in its implications that we probably cannot really anticipate where it will lead. But the new employment contract seems a reasonable direction, and it fits in nicely with other important facets of work today, to which we now turn our attention.

Teleworking

As Chapter 1 showed, the drive to make IT systems cheap, powerful, and convenient is producing a revolution in work that will enter the mainstream soon. Roughly forty million Americans were engaged in various forms of teleworking in 1994, and that number is growing 50 percent per year as the cost of ever more powerful information systems drops by a factor of ten every few years.13

People will always need personal contact, and there are problems working in an “electronic cottage,” to be sure. But teleworking offers convenient ways to augment face-to-face meetings as information systems become user-friendly and inexpensive. Rather than permanent employees working 9 to 5 within the same building, then, this mode of “electronically mediated work” will transcend previous restrictions of time and place. In a world of such vast possibilities, the idea of having employees dutifully report to their supervisor becomes positively quaint. Under the new employment contract, however, things look more reasonable. With accountability established, teams can use IT capabilities to work wherever and whenever they think best. Box 6.3 describes signs of speeding traffic along the information superhighway.

Working at home now becomes a feasible option. At one time, a home office was an embarrassment because it implied the lack of a regular job, but now it has become trendy. Pick up any magazine and you will see photos of lavish home offices equipped with the latest information systems, beckoning the high-pressured executive to unwind in a tranquil setting and release the creative intellectual within. “The biggest benefit is that I can maintain a full schedule while also being involved in my family,” said one consultant.

But there are costs. “You can’t leave because it’s always there,” said a saleswoman. Employees working at home often worry that they are not noticed being productive, and supervisors get uneasy not being able to supervise. A manager at Bell Atlantic says some telecommuters are “afraid to go to the bathroom for fear of missing a phone call from the office.”

This does not mean that we will become hermits slaving away alone in our homes. The growth of electronic communications is unlikely to replace direct interaction because people will always seek opportunities for contact with others at work, at school, and in other settings. However, information systems will become a viable alternative to the real thing as IT grows more convenient, so we will use these systems to augment personal contacts. Travel is becoming ever more time consuming, environmentally damaging, wasteful of energy, and hectic; all this increases incentives to use IT part of the time while maintaining social relations through occasional direct contact.

A survey conducted in 1987 found that 56 percent of respondents would continue to go to the office every day if given the choice of working at home electronically, 36 percent would split their time between home and office, and only 7 percent would work at home exclusively.14 Recent studies I have conducted show a similar mix of acceptance, but with a somewhat stronger leaning more toward combining office and home work.

This is the direction professional groups are moving in, particularly salespeople, consultants, and others who must work in the field. In 1993 Compaq Computer automated its routine saleswork by offering clients toll-free information lines for inquiries, and then shifted its entire sales force into home offices to make them more effective as traveling consultants. Each salesperson was provided state-of-the-art IT systems (high-powered PC notebook, fax, copier, cellular phone, access to centralized account listings) and other needed support. Revenues doubled while the sales force dropped by one-third. IBM is making similar changes. So many managers are now routinely connected to their offices using portable IT systems while traveling that they have been defined as a new breed of “perpetual motion executive.”15

Plans are also under way to achieve a happy compromise between working at the office and working at home. Employers want to spare their people long trips to offices in urban centers, yet managers often feel uncomfortable allowing employees to work at home. One solution is the “telework center”—a satellite office containing IT equipment that enables employees to work in their neighborhoods. The U.S. government established such centers around the Washington, D.C., area, and Pacific Bell has been operating centers in California for years.16 Similar centers are being experimented with in European countries and Japan. If this trend continues, the conflict between working at home and working at the office could be resolved by an intermediate solution—working in a satellite office near home.

Contingency Work

A related trend involves the many people who are joining the “contingent work force” of part-time employees, temporaries, and other marginal groups. The contingency work force comprised one-third of American workers in 1994 and is growing so rapidly it should include roughly half by 2000. “A tremendous shift to contingency work is under way,” observed an economist.17

This is not a temporary solution to the lack of regular jobs, but a major shift to an independent, more mature mode of “self-employment.” Contingency workers are becoming true knowledge entrepreneurs who take charge of their careers by packaging themselves as self-employed contractors able to move from company to company, consultants working for various firms, and individuals starting their own businesses.18 About 20 percent of all professionals now work as “temps,” including lawyers, doctors, and even executives. “The temporary executive is now a permanent fixture in American corporate life,” claimed an executive recruiter.19

Self-employment is attractive to many people and it provides important professional services to large organizations. Many individuals prefer the freedom, challenge, rewards, and excitement of being on one’s own. After all, what better way to fully satisfy those higher-order longings? Despite the low pay and benefits of marginal continency workers, studies find the average pay of self-employed people is 40 percent higher than that of their employed counterparts.

And companies like working with small suppliers because they minimize costs and bureaucracy and are usually more competent. AT&T buys goods and services from 100,000 small companies. “Small firms have an advantage,” said AT&T’s director of procurement. An entire infrastructure of home equipment, professional associations, and other services is springing up to support small entrepreneurs. One firm called “HQ Inc.” leases office space, secretarial services, meeting rooms, and anything else fledgling CEOs might need at 152 locations. “We provide instant credibility for startups,” said the president of HQ in New York City.20

IT also encourages an easy-flowing exchange of people between these two sectors. Large companies are increasingly trolling through information services to find small suppliers, and vice versa. A company representative described his experience finding specialized consultants over the Internet: “I can get fifty responses in a few minutes.” Telecommuting at home often leads to taking the leap into starting one’s own business and, conversely, selling one’s services to a large company often leads to a regular job.

A useful way to grasp this upheaval in work is to see that employment has now spread out along a continuum. At one end is the traditional full-time job, while at the other end is the self-employed entrepreneur. The new employment contract lies at the middle of this continuum, offering a loose association with the employer but also the autonomy of the entrepreneur, something like “in-sourcing” rather than “out-sourcing.” In this strategic position, it acts as a gatekeeper, allowing the speedy passage of employees to and fro to suit their needs as well as those of organizations. With the death of company loyalty to workers, employers can no longer offer secure employment, but they can assist people in moving along this continuum.21

What will it feel like to work this way? Box 6.4 presents a hypothetical scenario that projects current trends into the year 2000 to convey the feel and flavor of a typical knowledge worker’s daily life. Vera Pace is a member of a team that develops biofactories for its parent company, Biotronics, and for other organizations as well. If you have trouble imagining yourself in this setting, think of people living a mere hundred years ago. What would they have thought to witness today’s world of TV, jet flight, and supermarkets? The world of Vera Pace may be equally unsettling, but it will be no less real very soon.

WORK LIFE IN THE INFORMATION AGE

This restructuring of work life is not without its problems. New technologies must automate old processes, work must be reorganized into self-contained clusters of activities performed by teams, performance goals and incentive plans must be defined, and organizational architectures need to be established to support this system. The social problems of self-management can be especially knotty. Jon Hart, president of Overly Manufacturing, summed up how he experienced the change: “It’s like Pandora’s box. You open up the door and everything comes out.”

Some union leaders claim that teamwork amounts to a system of “management by stress,” intended to push workers to maximum productivity, so they are trying to reverse this trend.22 Yes, people can be exploited, but rather than oppose these inevitable changes, unions should look after the interests of labor constructively. As one union leader put it: “The union’s job is to prevent management from speeding up the line. There’s nothing inherent in work-team systems that has to be stressful.”23

There is also a dawning realization that these changes are not a one-shot thing, but a more demanding new way of work life with no end. The comfortable days of coasting along in a hierarchy, typified by the old Broadway musical “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” are over. “In ten years, anybody who runs a business on the old model isn’t going to be in business,” said the owner of a manufacturing firm.24

We should also caution that a large class of unskilled workers may be unable to compete in the demanding new world of knowledge work. Even with good educations and remedial social programs (a generous assumption), some sectors of society are likely to become chronically marginalized, leading to unemployment, crime, and other disorders. In The Bell Curve, his controversial work on intelligence, Charles Murray described the prospect of life being governed by a “cognitive elite”:

The twenty-first century will open on a world in which cognitive ability is the decisive dividing force in determining where an individual will end up. Unchecked, these trends will lead toward something resembling a caste system.25

This threat is real but not inevitable because our growing power to spread knowledge should allow anyone to be educated effectively, and human nature is far more malleable than we commonly think. We should also bear in mind that sophisticated information systems can increasingly support people in doing tasks that would otherwise beyond their abilities—some call it “just-in-time training.”26 The real issue is finding the political will and the personal discipline to address such problems.

Working with Flexibility

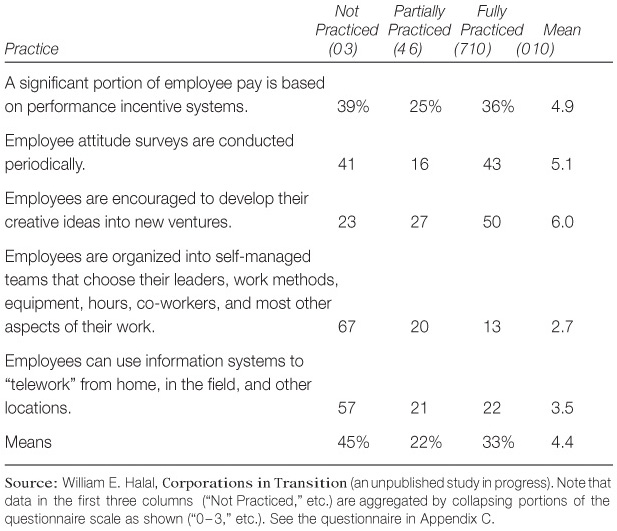

Table 6.1 shows how widely this new work role is practiced now, and the idea should continue to spread simply out of the hard necessity of coping with an avalanche of change. One manager expressed the prospects succinctly: “This will be common practice for just about any firm in the near future.” This more sharply focused business arrangement should provide people in an Information Age the entrepreneurial freedom and resources to work as they choose, while also providing organizations the freedom and productivity they need to compete.

Organizations are destined to confront more turbulence in the next ten years than we have ever experienced, which will require an exceptional degree of flexibility. Self-managed work teams will be essential to create organic structures composed of interchangeable modules that can be added to meet a rush of demand, dropped during a downturn, revised to obtain a different mix of skills, and so on.

People increasingly need the same flexibility to cope with the hectic nature of modern life. Now that the two-career family is the norm, both men and women must choose their time and place of work in order to balance the demands of job, family, education, and who knows what else. Jake Mascotte, CEO of Continental Airlines, noted: “So much of business is still structured like fourth grade.” In 1990, Continental began encouraging telecommuting, stopped tracking absences, and instituted other family-friendly practices. Productivity rose and turnover fell.27

Flexibility will also be indispensable in handling the unique needs of older people, young people, minorities, the handicapped, and countless other groups of workers who would otherwise pose special problems. And despite much talk of empowered workers seeking self-fulfillment, the fact is that many people do not really want to take on such responsibility; the nice thing about the new employment contract is that teams can manage their affairs in whatever style they prefer: a full-fledged democracy, some sort of spiritual unity, or old-fashioned authoritarian leadership. The extensive skills of those who focus on behavioral issues (human resource management, organizational learning, project management, and the like) will be invaluable for making this diversity work effectively, and for helping teams work together to form complete corporate communities.

Most of the complex trappings we think of as indispensable parts of a job may disappear. The proportion of employers offering medical benefits has dropped from 84 percent in 1982 to 56 percent in 1995. Annual reviews, supervisors, step grades, training programs, and so on are all declining in use. Why should anyone want to engage in this ancillary busywork when their real interest is to get their task done effectively? Listen to how author William Bridges described the simplifying advantages of being freed from our old notion of a “job”:

What would happen to our present policies on leave of absence, vacation, retirement, etc.? Leave from what? Vacation from what? Retirement from what?28

Accepting Self-Responsibility

These are the main features that should mark work life in the year 2000 or so:

1. The natural evolution of economies is likely to make a new phase of knowledge work common in a decade or so.

2. The old employment relationship in which people were paid for holding a “position” is dying because it is too confining for a turbulent economy, leaving employees without secure work roles.

3. Knowledge workers should ideally be organized into self-managed teams that are free to control almost all aspects of their operations and are rewarded for team performance.

4. This system should permit both employers and employees to use alternatives such as teleworking and contingency work to gain the flexibility needed to cope with a dynamic economy.

Like most academics, I spend about half of my time working in a self-employed status at home and with a variety of organizations, and I find that it requires great self-discipline. Indeed, that is both the greatest advance as well as the greatest challenge of the new employment contract. It requires managers to treat workers as fully competent adults, and workers in turn must accept the responsibility for carrying out their tasks diligently. Although the demands are hard, I cannot imagine working any other way.

Despite the daunting nature of these challenges and the failures that are certain to come, the new employment contract seems likely to roll on. For all the pitfalls of performance pay, for instance, most managers believe in the concept because it represents an important future direction. “We don’t think the alternative—paying everyone the same—is better,” said John Hillins, vice president for corporate compensation at Honeywell.

Organizations are being transformed by the Information Revolution into a fine web of small, automated systems, managed in real time by changing assemblies of self-employed teams, with such complete information available that their behavior becomes transparent. It’s not going to be easy, but this historic transition promises to eliminate the drudgery long associated with work, thereby freeing people for the more sophisticated tasks that now form the principle challenges facing a knowledge-based economy.

Notes

1. Alex Gibney, “Paradise Tossed,” Washington Monthly (June 1986).

2. Andrea Gerlin, “Seminars Teach Managers Finer Points of Firing,” Wall Street Journal (April 26, 1995).

3. Lars-Erik Nelson, “Unwelcome Guests,” Washington Post (August 14, 1995). William B. Johnston, “Global Work Force 2000: The New World Labor Market,” Harvard Business Review (March-April 1991).

4. This point is effectively made by Robert Reich in The Work of Nations (New York: Knopf, 1991).

5. See the annual survey of the American Council of Education, UCLA.

6. A sound analysis of these trends is provided by Nuala Beck, Shifting Gears: Thriving in the New Economy (New York: Harper Collins, 1995).

7. G. Pascal Zachary, “Service Productivity Is Rising Fast,” Wall Street Journal (June 8, 1995).

8. See the special report “The Technology Payoff,” BusinessWeek (June 14, 1994), and Myron Magnet, “Good News for the Service Economy,” Fortune (May 3, 1994).

9. Ramchandran Jaikumar, “Postindustrial Manufacturing,” Harvard Business Review (November-December 1986).

10. William Bridges, “The End of the Job,” Fortune (September 19, 1994).

11. Jay Mathews, “Do Job Reviews Work?” Washington Post (March 20, 1994). The Conference Board Briefing (July-August 1989), and “Bonus Pay,” BusinessWeek (November 14, 1994).

12. For instance, the well-known studies by Frederick Herzberg showed that pay, benefits, and other “extrinsic” factors were necessary to prevent people from feeling dissatisfied with their work, while challenge, creativity, and other “intrinsic” factors were also necessary to provide active motivation.

13. See William E. Halal, “The Information Technology Revolution,” Technology Forecasting & Social Change (1993), Vol. 44, pp. 69–86.

14. “Home or Office?” Wall Street Journal (March 31, 1987).

15. Michael Malone, “Perpetual Motion Executives,” Forbes ASAP (January 1994).

16. Mitch Betts, “‘Telework’ Hubs Sprout in Suburban America,” Computer World (July 22, 1991).

17. Jaclyn Fierman, “The Contingency Work Force,” Fortune (January 24, 1994). Peter Kilborn, “New Jobs Lack the Old Security,” New York Times (March 15, 1993).

18. For a fine account of this perspective see Cliff Hakim, We Are All Self-Employed (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1994), and Kenneth Labich, “Take Control of Your Career,” Fortune (May 1992).

19. “Part-Timers Are In,” Conference Board’s Monthly Briefings (March 1988); “And Now, ‘Temp’ Managers,” Newsweek (September 26, 1988).

20. Liz Spayd, “Growing Ranks of Self-Employed Reshape Economy,” Washington Post (April 4, 1994); Brian O’Reilly, “The New Face of Small Business,” Fortune (May 2, 1994).

21. Brian O’Reilly, “The New Deal,” Fortune (June 13, 1994).

22. See Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter, “Management by Stress,” Technology Review (October 1988); “UAW Delegates Dispute ‘Jointness,’” Washington Post (June 24, 1989); and “Workers Aren’t Anxious, They’re Proud,” Washington Post (October 29, 1988).

23. John Hoerr, “Is Teamwork a Management Plot?” BusinessWeek (February 20, 1989).

24. Marc Levinson, “Playing with Fire,” Newsweek (June 21, 1993).

25. Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: The Free Press, 1994).

26. Lewis J. Perelman, School’s Out (New York: Avon, 1992). Tim Ferguson, “Help! How Best to Avail the Labor Force,” The Wall Street Journal (May 16, 1995).

27. “Work & Family,” BusinessWeek (June 28, 1993).

28. Bridges, “The End of the Job.”