3

From Profit to Democracy

Corporate Community Is the New Form

of Organization Governance

A division manager of a large corporation I know (Steve) was struggling with a chronic dilemma. He was under pressure from senior management to increase his unit’s profits, but all attempts failed. Raising prices and cutting corners to lower costs merely irritated his clients as they began to feel gouged. Making greater demands of employees backfired because they felt overworked. And negotiating tough terms with suppliers and creditors also provoked resistance. After discussing the problem at length with Steve, I suggested that he might be focusing too exclusively on profitability—any goal can become elusive if one tries too hard.

The idea seemed to catch his interest, setting off a serious reexamination of his goals and working relations. A few months later Steve’s division was absolutely humming with energy. He had redefined his unit as a “cooperative enterprise” jointly managed by himself, his employees, suppliers, and even his clients. This was the result of much serious soul-searching and frank discussion, leading to the realization that the best way to gain the support of people was to engage their interests.

Now Steve’s employees were designing and managing their own operations, and they were eager to take on these responsibilities because they received a generous share of the division’s profits. The division’s clients became faithful patrons after visiting Steve’s staff to describe their special needs and to work out problems. A similar relationship was developed with suppliers.

Note: Portions of this chapter are adapted from Chapter 6 of my earlier work, The New Capitalism (New York: Wiley, 1986).

The outcome: Steve’s division reached its higher profit goals, but it did so by focusing on the needs of its constituents. Steve also felt delighted at the new spirit of his organization. Rather than the demanding boss he had been, he could enjoy working with these people in a constructive way.

Human nature is not turning altruistic, but progressive managers like Steve are creating a new form of corporate governance that unifies the goals of all parties. This chapter describes the democratic half of the New Management that focuses on integrating an enterprise into a harmonious whole—a corporate community.1 Secretary of Labor Robert Reich observes that a telling sign of good management is that employees speak of the company in terms of “us” and “we” rather than “them” and “they.”

The following pages outline the limitations of the old profit-centered model of business and the social responsibility model. Then we examine the evolution of corporate goverance toward collaboration among all stakeholders of the firm. This move from profit to democracy implies creating a coalition of investors, employees, customers, business partners, and the public, thereby forming a corporate community that serves all interests better.

I conclude that economics is likely to be elevated to include a broader concern for social and human values. This should not harm the financial goals of business because they are compatible with social goals. In fact, the pursuit of both goals may be a “better way to make money.” From the view of the New Management, however, the concept of corporate community could prove so effective that the profit-centered system once thought to be intrinsic to the marketplace may soon become an artifact of the industrial past.

THE EVOLUTION OF ECONOMIC COOPERATION

The issue of corporate goverance has always been contentious because of basic assumptions about economic behavior. Throughout industrialization, business was usually considered a zero-sum game in which one party gained at the loss to another. This conflict is most apparent in the continuing controversy over whether companies should focus on making money or serving society. But with the onset of a knowledge economy, all that has changed. As today’s rush to alliances demonstrates, cooperation has now become efficient.2

Limits of the Profit Motive

The profit motive is so deeply ingrained in present economies that most of us cannot imagine how business could be conducted otherwise. Ask an average American if business should focus on profit, and you will probably get a blank stare at such a dumb question. Indeed, you are likely to hear an adoration of wealth because most Americans hold out the hope of striking it rich themselves. Making money is part of the American dream.

In general, Americans have faith in the capitalist theory that profit is the driving force of economic progress. The profit motive should motivate business to satisfy customer needs, employ workers effectively, use scarce resources efficiently, and otherwise serve society. The problem, of course, is that the messy realities of economic life do not fit this theory very well.

A major cause of this problem is that in the zealous pursuit of money, managers are often encouraged to disregard social consequences. As we can commonly observe, many companies make lavish profits—even as they lay off workers, evade taxes, pollute the environment, and cause other social disorders. A study by Amitai Etzioni found that 62 percent of the Fortune 500 companies had been involved in illegal practices over the last ten years.3 Other studies estimate the cost of price fixing, pollution, bribes, work injuries, product defects, and other white-collar crime to total several hundred billions dollars per year, a major portion of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).4

Let’s be clear about what is going on here. The cause is not primarily attributable to “greed,” as we often hear, because most business managers are moral, dedicated professionals trying to do a difficult job as best they can. Rather, the problem is systemic. As shown in Figure 3.1, the profit-centered model is based on an ideological system that focuses on serving the interests of those owning capital—shareholders. In this view, the interests of employees, customers, the public, and other stakeholders are not really goals of the firm, but simply a means to making money.

FIGURE 3.1. THE EVOLUTION OF CORPORATE COMMUNITY.

Capitalism has great virtues, and many companies behave admirably, as we shall soon see. However, if the goal of enterprise is defined as profit making, the interests of business are opposed to the interests of society. Any philosophy devoted to “taking” contradicts the values of almost all religions, which advocate “giving” to serve others. The Reverend Billy Graham put it this way: “The biggest problem facing America is the moral situation, the scandals in business and Wall Street.”

Limits of Social Responsibility

In an attempt to remedy this problem, about three decades ago American business sincerely tried to adopt the concept of “corporate social responsibility” (CSR), as also shown in Figure 3.1. Corporations voluntarily created programs to improve the treatment of their social constituencies, and they even attempted to measure this progress using “social audits.”5

But the idea became an empty piety because it focused on “doing good” while ignoring the need to increase productivity, sales revenue, and profits. A similar fate is likely to befall today’s successor to CSR—the rising popular interest in business ethics.

These concepts have been useful in educating businesspeople about their social obligations. However, social responsibility is a limited idea because it goes to the opposite extreme by advocating social service while ignoring economic realities.

The Conflict Between Business and Society

This continual conflict between profit and the social welfare has left societies bereft of what economists call a workable “theory of the firm.” As Irving Kristol put it, “Corporations are highly vulnerable to criticisms of their governing structure because there is no political theory to legitimate it.”6

The problem also extends into social institutions, with serious consequences. The role of news media is crucial in a knowledge society, yet media empires are controlled to serve financial interests. After CBS was bought by Lawrence Tisch in 1987, he fired six hundred newspeople to improve profits. Yet stars like Dan Rather were being paid several million dollars each, about as much as the savings from the layoffs. This type of logic raises puzzling questions.

Is Dan Rather really worth more than hundreds of his colleagues? CBS was already very profitable, and the layoffs harmed CBS news coverage. Why is increasing the wealth of Tisch more important than the lives of his employees, and more important than serving the public better? Here’s how a typical worker sees it, “It doesn’t make sense. You can see them cutting people to get out of a bind—but just to make more profit? I don’t get it.”7

It was even harmful from strictly financial considerations. CBS’s viewer ratings declined, profits plunged 68 percent, major executives went elsewhere, and affiliates switched to other networks. (David Letterman quipped on his night show, “You’re watching CBS, the network that asks the question: ‘Hey, where did everybody go?’”) As a result, CBS was sold to Westinghouse for $6 billion, while ABC was sold to Disney for almost $20 billion.8

The same problem occurs in organized sports. Ask any fan or city official and they will confirm that baseball, football, and other sports are quasi-public institutions of enormous symbolic importance to their communities. Cities invest billions of dollars in building stadiums, fans provide loyal support and buy expensive season tickets, high schools and colleges invest years in training the players, and the media provide lucrative TV contracts.

Yet these groups have no rights. Owners can move teams to other cities at will. They set the price of admission and franchises to vendors. They draft young players in a form of servitude, and enjoy exclusive rights to control play in their city. The result is that this beloved public function is accorded the status of a monopoly under the sole control of owners.

It should be no surprise that a stream of disturbing incidents flows from this unchecked power. The baseball strike of 1994 so angered fans that some organized to negotiate with the owners, and 25 percent boycotted the game when play resumed in 1995; low attendance will cause the owners to lose $400 million in 1995.9 When the owner of the Washington Redskins threatened to move the team to another location, a prominent Washingtonian had this reaction: “The Redskins aren’t only a business for this region; they are a unifying institution for most of us who live and work here … a central force in bringing pride, cooperation, and a sense of oneness to the metropolitan area.”10

Although some managers may try to balance profit and these social interests, they are constantly swamped with financial data, scrutiny by Wall Street analysts, and the threat of takeover. These powerful forces crowd out social concerns and their sheer inertia resists change. That’s why noble mottoes such as “Our customers come first” and “Our employees are our most valuable asset” are usually mere platitudes. In an age when it is commonly understood that knowledge, satisfied customers, and a committed work force are critical to economic success, one can only marvel that we continue to treat corporations as chattel to be “owned” by investors.

Why have smart, proud citizens of the most powerful nation on Earth voluntarily yielded the power to control the major institutions of their society? Because money holds the status of a reigning theology in America. It is a sacred cow that cannot be questioned, a dogma that blinds us to a more complex reality. Profit making, the rights of ownership, and other canons of capitalist ideology constitute the de facto religion that governs our fading Industrial Age system, roughly the way medieval Christianity governed the agrarian societies of the Middle Ages.

Medieval civilization was dominated by the church: massive Gothic cathedrals provided the focus of city life; daily tasks were centered around the rhythms of mass and prayer; and society was guided by a hierarchy of priests, abbots, and bishops. Today, civilization is no less dominated by capital: massive corporate offices buildings have replaced the cathedrals; leveraged buyouts, hostile takeovers, and arcane derivatives have replaced the religious rituals; and the church’s hierarchy has given way to a hierarchy of accountants, security dealers, and financiers.11

The Rise of Stakeholder Power

Within the past few years, however, powerful trends in corporate governance suggest that serious change is under way.

For decades, control of large corporations resided almost solely with the CEO, while the corporate board and stockholders provided a fig leaf shielding our eyes from this naked display of unilateral power. Few believed that the typical board of directors was much more than a social gathering of the CEO’s associates, and the annual stockholder meeting was widely ridiculed as a farce. Only a small portion of shareholders attended; they were unorganized, poorly informed, and usually preoccupied with trivial complaints that seemed mainly intended to humble corporate executives. “It’s the only forum that makes Congress look good by comparison,” noted Robert Monks, a major institutional investor.

But now stockholders, employees, and other stakeholders are steadily gaining power.

Institutional shareholders—pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, banks—own the majority of stock at many large corporations. The California Public Employees Retirement System (CALPERS), one of the largest pension funds, began using its untested power in 1990 to influence poorly managed corporations, which brought about the fall of CEOs at GM, IBM, Sears, American Express, and other troubled firms. Today, most large corporations regularly meet with their institutional investors.12 This relationship has been shown to improve financial performance, so large investors have become permanent players in the management of large corporations.13

Another new force in corporate governance is the rising power of employees, as we will see in Chapter 6. Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) control 12 percent of all corporate stock, and employees sit on the boards of three hundred large corporations. At some large companies, such as United Airlines, workers own a majority of shares. Further, the ESOP movement is growing 10 percent per year.

Women are also becoming more influential in corporate governance, thereby introducing a new set of “feminine” values that stress a more humane, community-oriented form of management. Women sit on most corporate boards, and one-quarter of all new corporate directors are now women. The number of businesses owned by women is growing more rapidly than those owned by men.

Other social constituencies have also gained influence in recent years. As we will see in later chapters, almost all companies now strive to build trusting long-term relations with their customers; they work closely with their suppliers and distributors, they are developing partnerships with government, and they voluntarily protect the environment.

Finally, the legal barriers are being eliminated. American law once presumed that stockholders were the sole beneficiaries of the corporation, but this is changing. “What right does someone who owns the stock for an hour have to decide a company’s fate?” asked Andrew Sigler, chairman of Champion International. “That’s the law, and it’s wrong.” At last count, thirty states have adopted statutes that recognize the interests of corporate social constituencies, and the concept is spreading to most other states.14

These trends have accelerated the movement toward a broader form of governance. In 1992, fifty companies, including Levi-Strauss, the Body Shop, Stride-Rite, Reebok, and Lotus, formed the Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) alliance, and a year later membership leaped to eight hundred companies. This is only the most visible example of a broader movement that includes the World Business Academy, the Social Venture Network, and many other groups of progressive business managers and scholars.15

Unlike the old form of social responsibility, today’s movement admits the need for financial gain. “We are here to get people to recognize that there is a link between profitable performance and responsible corporate practices,” said Michael Levett, former president of BSR.16 In 1984, investors concerned with social criteria (ethical treatment of employees, product safety, environment, etc.) owned $40 billion of corporate stock, while in 1990 that sum passed $500 billion.17

What all these trends share in common is that stakeholders who previously remained passive are now demanding to be heard. “There’s a populist wind blowing through this country,” said Ralph Whitworth, president of the United Shareholders Association. “We see less willingness to accept the status quo, whether it’s in Congress or in a corporation.”

How are managers going to handle this revolution of the stakeholders? By redefining a broader, more effective role as “stewards” of this emerging corporate community.

The Stakeholder Model of the Corporation

This need can be better understood if we look at the stakeholder model. As shown in Figure 3.1, this model views the corporation as a socioeconomic system composed of various constituencies: employees, customers, associated firms (suppliers, etc.), the public and its government representatives, and investors. Please note that this model differs from the social responsibility model in that stakeholders have obligations to the firm as well as rights. This view has long prevailed among some companies, such as those discussed in Boxes 3.1 and 3.2. Now the idea is becoming widely accepted because managers realize that the success of their enterprise depends on gaining the support of these groups.

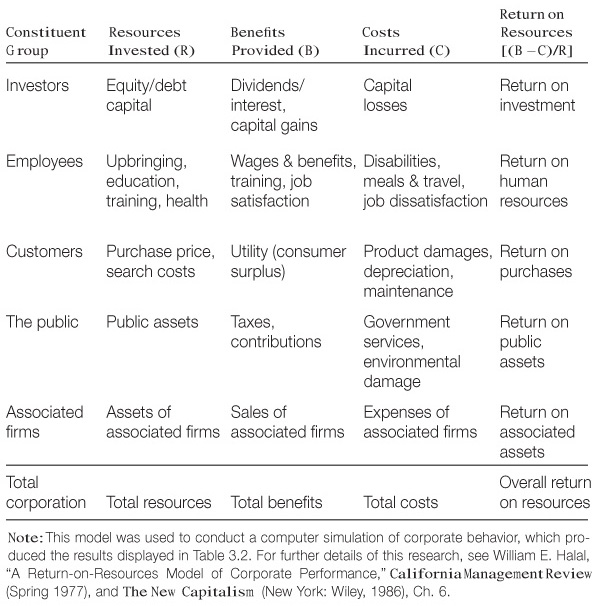

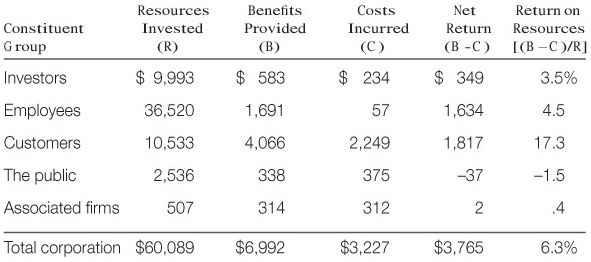

This essential role of social interests is clarified by my studies, which estimate the resource flows between stakeholders. The return-on-resources model and data in Tables 3.1 and 3.2 show that all stakeholders invest financial and social resources, they incur costs, and expect gains, just as investors do. These resources constitute their “stake” in the organization, which is so specific that it can be compared quite accurately to capital investments.

These data reveal how seriously limited is the traditional view of the firm that focuses on financial aspects alone. The total figures at the bottom of Table 3.2 are greater than the financial sums shown for investors by roughly a factor of ten. Thus, social concerns, which are usually regarded as “economic externalities,” are far greater than financial considerations because they comprise a vast but more subtle world of human and social realities that has eluded the Old Management.18 Hicks Waldron, chairman of Avon Products, described this reality:

We have 40,000 employees, 1.3 million sales representatives, a large number of suppliers, customers, and communities around the world. They have much deeper and more important stakes in our company than our shareholders.19

The data also show that all parties benefit. Business does not simply redistribute resources, as in a zero-sum game, but is inherently a productive institution that creates value for all its constituencies. Although the gains of various stakeholders may conflict in the short term, they are compatible in the long term. This is confirmed by various studies and common examples, which show that business creates jobs, educates people, pays taxes, and more.20

For example, the Body Shop is a socially oriented corporation, yet it is also very profitable. The difference is that profits are put in perspective as one goal among many. “Profits are jolly good,” said Anita Roddick. “But they are a means to a larger goal.” The Body Shop has built plants in poor areas, funded environmental projects, and made other efforts to combine both social and economic goals. “Now, that’s what you do with profits!” said Roddick.21

This analysis leads to a precise theoretical description of the nature of the firm. Corporate managers are dependent on stakeholders because the economic role of the firm is to combine as effectively as possible the unique resources each stakeholder contributes: the risk capital of investors; the talents, training, and efforts of employees; the continued patronage of customers; the capabilities of business partners; and the economic infrastructure provided by government. The need for capital is essential, of course, but the contributions of other stakeholders are no less essential. Because companies are socioeconomic systems, these functions are all as essential as the diverse organs of a body.

Thus, managers should act as stewards engaged in a “social contract” to draw together this mix of resources and transform it into financial and social wealth, which they can then distribute among stakeholders to reward their contributions. The closer the integration into a cohesive community, the greater the wealth.

The good news, then, is that there does not seem to be a conflict between profit and social welfare, as we will see more fully in the next chapter. Yes, stakeholders have different interests that flow from their unique roles in the corporate community, but these interests can be reconciled IF they are organized to create a more successful enterprise. All parties could thereby benefit, including investors. Thus, a more effective goal for business would be to serve the public welfare represented by all stakeholders. Henry Ford said the same decades ago: “People believe that the only purpose of industry is profit. They are wrong. Its purpose is the general welfare.”

The Coming Economic Copernican Revolution

Let me suggest an analogy that helps put these different views of corporate governance in perspective.

The profit-centered model of business is comparable to the Earth-centered model of the universe. Like the central role once attributed to the Earth, profit has been rather arbitrarily selected as the center of today’s economic universe because that is the view we inherited from an Industrial Age when capital was the primary factor of production. The social interests of stakeholders were placed in successively distant orbits as being of lesser importance, even though they may in fact be as huge as the Sun.

In contrast, the social responsibility model goes to another extreme by positing an economic universe that revolves about social interests but ignores financial realities. This is roughly equivalent to a solar system that revolves about Mars, Saturn, or Venus rather than the Earth.

I think this analogy clarifies the debate that continues to confuse all of us. Adherents of the Old Management who insist on the profit-centered model are roughly comparable to those who believed in an Earth-centered universe, while advocates of a social responsibility model can be seen as “prophets” or “revolutionaries” who proclaim that the universe revolves about other planets.

The stakeholder model reconciles this confusion by showing that all such interests are equally important. Shareholder wealth, employee welfare, customer satisfaction, the public good, and other corporate interests all revolve about a common economic goal that is as central to society as the Sun is to our solar system—serving the human needs of all these diverse members of the corporate community.

If this comparison is valid, it highlights the challenge facing managers, scholars, and others involved in developing a New Management. Just as the studies of Copernicus caused astronomers, philosophers, and theologians to accept a radically different theory of the universe, the data in this chapter indicate the need for an economic equivalent of the Copernican Revolution.

PRINCIPLES OF CORPORATE COMMUNITY

Theories and data can help us see a different reality, but how can such a dramatically different view be translated into practical guides? Based on studies and the experience of progressive companies, three central principles have been found useful: community spirit, performance evaluation, and stewardship.

Create a Spirit of Community

Like any other community, a human enterprise must be created by leaders—“stewards” who instill a vision of the corporation as a community united by commonly cherished values and principles.22 Because people in advanced nations today are hungry for this sense of belonging, there is a rising tide of interest.

The best example is offered in Boxes 3.3 and 3.4, where the close parallel between GM-Saturn’s philosophy and the stakeholder model can be seen. Richard “Skip” LeFauve, the chairman of Saturn, described his goal this way: “People have been an underutilized asset in this industry. Saturn’s mission is to change that by creating new relationships with the United Auto Workers, dealers, and suppliers. Saturn is more than a car, it’s an idea, a whole new way of working with our customers and with one another.”

To have such ideals accepted as a working part of day-to-day life, however, stakeholders must discuss, modify, and affirm these values, or they will remain a lofty set of platitudes. Levi-Strauss has taken the lead in shaping a corporate culture that actually behaves as an ethical community. Management drafted a statement outlining the values Levi-Strauss aspires to, and six thousand of the company’s thirty-six thousand employees provided suggestions on replanning corporate practices.23 A similar process was used by Johnson & Johnson some years ago.

Although this broader form of governance has advantages, institutional roles are always defined by personal beliefs. The reality is that many people feel keenly that business should be a strictly profit-making affair, and all the evidence in the world is not likely to sway them. It is also true that a human-centered form of business may not be useful in some industries, and it may not be acceptable for some national cultures.

For example, managers surveyed in the CIT study expressed a wide range of opinion on this point, usually in strong, emotional terms. A majority confirmed the importance of serving all interests: “Our goal is to serve all groups equally,” “The trick is balancing interests. How else could one operate?” But some believe in the primacy of clients: “Our primary goal is to make sure the client is satisfied,” and “The underlying reason for all our efforts is to provide the best product possible and to exceed the expectations of our customers.” And a few strongly affirm the traditional view: “Profit, profit, profit—for shareholders.”

These considerations remind us that changing institutional goals is uncharted territory. Subtle issues of personal values and political ideology are involved, which are poorly understood, and there is limited knowledge of the effects on economic productivity and society. A useful way to explore this domain is to gather useful information, which leads to the next topic.

Evaluate Stakeholder Performance

An old management axiom holds that one cannot manage what is not measured, and so evaluating the benefits and costs experienced by stakeholders is needed to guide decisions. Otherwise, how can managers know how well groups are benefiting? Which groups are receiving preferential treatment and which are being slighted? Where are the problem areas? What level of benefit is justified at what cost? And so on for other complex issues.

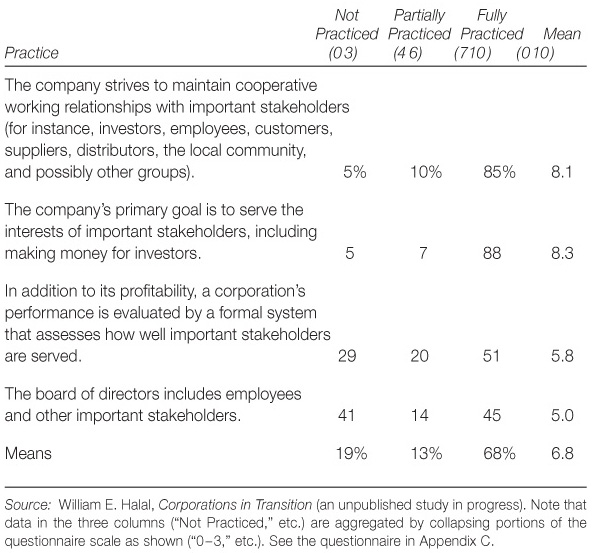

Corporations have developed systems for doing this in specific areas (such as evaluating the management of employees and customers), which we will survey in later chapters. Some broad frameworks have been used to provide a systematic evaluation of all stakeholders, but few organizations have attempted ambitious projects of this type.24 Box 3.5 shows the main systems of this type. A prominent advance is that the 1995 Fortune list of “America’s Most-Admired Companies” was heavily weighted by how well managers serve their customers, treat their workers, and behave responsibly to their communities, in addition to measures of profitability.

The best way to understand stakeholder evaluation systems is to see them as an extension of financial measures. Social data are used to manage social performance, just as financial data are used to manage financial performance. Both types of information can help managers understand the attitudes of various stakeholders, forecast trends, identify critical issues, and propose strategies to resolve problems. Estimating complex social factors is difficult, of course, but what we think of as “hard” data present much the same problem. Accountants know that arbitrary assumptions underlie statements of profit and loss, and economists have equally troubling questions about measures like the GDP.

In the final analysis, managers must constantly make decisions that guide their actions in such matters, and the availability of sound, comprehensive information systems of this type can only help by replacing ignorance with knowledge. If a fraction of the enormous costs now devoted to financial measurement were applied to social measurements, we would have a powerful tool for managing the community of corporate interests.

Provide Corporate Stewardship

An inspiring vision and sound information are useful, but ultimately managers have to put these into use with groups of stakeholders who may disagree vehemently. This is difficult terrain for any leader, but it is especially wrenching for corporate managers who are mired in a perennial role conflict over profit versus social welfare.

This lack of a well-defined, defensible role is a great dilemma for today’s large cadre of young professional managers who are struggling to sort out confusing issues between their jobs and their ideals. If a manager is a true professional, who is the client to be served? Only the investor, by making money? The boss, by following orders? How can managers gain the allegiance of subordinates if employees are secondary to profit? What does the professional manager do when the interests of employees, customers, and other groups conflict with making money? These tough issues have been made worse because the myth of the profit motive places managers in an impossible situation where their duties are opposed to the stakeholder groups on whom they are dependent.

The stakeholder model, however, defines a far more constructive, legitimate role that provides managers a strong sense of professional identity. From this view, managers are “servant leaders,” or stewards, responsible for serving the collective welfare of the constituencies that make up their organizations.25 They use their special expertise to help this community collaborate for their mutual benefit, and they are accountable to these groups, just as physicians and attorneys are accountable to their clients. CEO George Fisher set a bold challenge for the managers at Kodak by tying his annual compensation to performance measures that are weighted by 50 percent for stockholders, 30 percent for customers, and 20 percent for employees.26

Role-playing a “stakeholder meeting” can help people understand how to manage these complex interrelationships. This exercise, contained in Appendix B, asks five to ten people to simulate a company meeting to which representatives of all stakeholder groups have been invited. The impact can be profound because the abstract idea of the corporation as an extended socioeconomic community comes vividly to life, offering rich opportunities for exploring the role of corporate stewardship.

Remember that stewardship is not intended to “do good” in the sense of performing philanthropic deeds that give things to others, which is why concepts such as social responsibility and business ethics have had limited effect. Sound stakeholder management is a pragmatic, two-way set of collaborative working relationships between the corporate community and its members that benefits the enterprise as a whole. Because value can be distributed only to the extent it has been created, the role of corporate stewards is to ensure a match between contributions and rewards. The establishment of this reciprocity between what one creates and receives is fundamental to the health of any community.

A large body of research shows that organizations define and enforce subtle norms to set an appropriate balance between the benefits each individual or group receives versus the contributions they make. If some group is slighted, they correct this imbalance by withholding contributions to reestablish equity. This sense of equity is so precise and so strong that one idealistic CEO tried a system in which employees could simply ask the paymaster to give them any sum for their regular pay. It seemed to be an outrageous idea that would be wildly abused, but it actually worked pretty well. Very few people asked for more than small increases, and almost all realized they were fairly paid by a considerate employer.

These powerful norms of equity mean that managers cannot usually obtain more from their constituents than they consider to be reasonable. Managers must earn their contributions by providing corresponding benefits. Methods for evaluating stakeholder performance are useful to guide the give-and-take bargaining needed to reach agreement. But to make such complex, trusting relationships work, a new breed of manager is needed who can provide skillful leadership. As we will see in Chapter 9, good leaders today inspire others to share responsibility for the enterprise. They listen to really hear different points of view, build bridges between conflicting interests, and are generally skilled in the political art of forming coalitions.

Data from the CIT survey (see Table 3.3) indicate that this type of collaboration is occurring to some extent. The majority of managers today cooperate with stakeholders and try to serve their interests, but a third do not evaluate stakeholder performance and almost half do not seat stakeholders on their boards. One manager in the CIT survey highlighted the problem: “Our board is comprised of nine white, affluent, males with no females or minorities.”

If it makes sense to cooperate with stakeholders, the logical conclusion would be to meet with them periodically. For instance, if managers really want to serve their customers better, why have responsible clients and consumer advocates remained so conspicuously absent from corporate boards? When Louis Gerstner replaced John Akers as CEO of IBM in 1993 and was exploring ways to revitalize Big Blue, a prominent analyst advised the following: “If Gerstner is sincere, he should create a new board made up of IBM customers, suppliers, partners, employees … a new kind of IBM that couldn’t help but be more responsive because the people in charge represent the company’s future … and clearly signal that business as usual is dead at IBM.”27

This same concept can be used throughout the organization. Russell Ackoff has proposed an ambitious form of decentralized corporate governance in which lower-level boards set policy for each product division or major project. Membership on these miniboards can include stakeholders, support personnel, higher and lower level groups, and so on. At Hewlett-Packard, for instance, each major project is governed by a cross-functional board, and many other corporations use boards to govern individual divisions.28

THE EXTENSION OF DEMOCRACY

The evidence we have surveyed leads to the following conclusions:

1. Corporations lack a workable theory of governance because the profit and social responsibility models ignore the reality that business is both an economic and a social institution.

2. The stakeholder model resolves this conflict by treating all corporate interests as equally important constituencies that receive benefits in return for their contributions.

3. Collaboration with corporate stakeholders is occurring now as investors, workers, women, clients, the public, and other interests gain increasing power and because managers need their support.

4. A corporate community of stakeholders offers the possibility of increasing both the benefits to social constituencies and profits for investors.

Some cautionary points should be noted. This more complex system of governance could become unwieldy, time-consuming, and emotionally disruptive if managers are unable to handle the political tensions that are inevitable; as we will see in the next chapter, corporate community may be inspired by our ideal of democracy, but managers are likely to avoid this problem by using an informal system rather than some form of representative government. It is also true that the practice of human enterprise is not likely to become universal since it may not be appropriate in some industries nor desired by some people. Instead, it may become established only in large, quasi-public institutions, such as the Fortune 500 companies, and among an avant garde of progressive business leaders. Even in these cases there will always be occasions of doubtful ethical behavior. Dow Corning was lauded for its model code of ethics, but this failed to avoid the crisis that erupted over the dangers of its silicone breast implants.

These limitations notwithstanding, the transition to corporate community should prove a watershed in economics. Driven by the liberating power of information, the benefits of cooperation, and the rising aspirations of modern people, democratic ideals are being extended into daily life to form a powerful new model of business that is increasingly productive and socially beneficial.29

This historic change should also help resolve other nagging problems that have long resisted solution. Inflation could be better controlled because a unified corporate community would spur productivity while also constraining wage and price demands. Growth may be directed in more fruitful avenues as unmet social needs are better understood and responded to more directly. Hostile takeovers may become a thing of the past, since the firm would not be simply chattel to be bought and sold but a community governed by its constituencies. Government regulation could be minimized because business could become a relatively self-regulated system, reducing the need for external safeguards. The concept will not be limited to business, but should change government and other social institutions as well.30

Those who favor traditional views should note that this concept does not clash with the profit-centered model. In fact, the stakeholder model is a logical extension of Western ideals. As I stressed in the Introduction of this book, the New Management does not refute the Old Management but goes beyond it to provide more powerful ideas that absorb their older versions. Einstein’s reformulation of physics did not prove that Newton was wrong; it was simply a special case of Einstein’s more general theory. Likewise, the human enterprise does not imply that profit is bad; rather it is a special case of the general concept that business should serve multiple goals, one of which is profit. Corporate community can be thought of as a better way to make money, possibly even more money.

Beyond this rationale of the Old Management, however, this New Management view holds the promise of resolving the business-society conflict that has plagued capitalism for two centuries. Daniel Bell called it “the cultural contradictions of capitalism”—that destructive clash between the hard necessity of survival in a market economy and the ideals of human cooperation and social welfare that we aspire to in a democratic society.

In an age torn apart by conflict, corporate community may prove our main bulwark against civil decay. Because business is the most powerful institution in modern society, managers could take a great step forward in human affairs by developing this badly needed ability to cooperate for the benefit of everyone.

Notes

1. For a fine recent survey of views on corporate community, see Kazimierz Gozdz, Community Building (San Francisco: Sterling & Stone, 1995).

2. The classic work on this topic is by Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

3. Amitai Etzioni, “Shady Corporate Practices,” New York Times (November 15, 1985).

4. Mark Green and John F. Berry, “Corporate Crime,” a two-part report appearing in The Nation (June 8 and 15, 1985).

5. William E. Halal, The New Capitalism (New York: Wiley, 1986), Ch. 6.

6. Irving Kristol, “‘Reforming’ Corporate Governance,” Wall Street Journal (May 12, 1978).

7. Matt Murray, “Amid Record Profits, Companies Continue to Lay Off Employees,” Wall Street Journal (May 4, 1995).

8. Elizabeth Jensen, “CBS’s Tisch Is Faulted,” Wall Street Journal (May 22, 1995).

9. “Kevin McManus, “Baseball Fans: Strike Too,” Washington Post (October 9, 1994). Allen Sanderson, “Break Up Baseball,” Washington Post (December 9, 1994).

10. Sterling Tucker, “The Redskins: More than Just a Business,” Washington Post (July 24, 1992).

11. This point is nicely made by James Robertson, Future Wealth (New York: Bootstrap Press, 1990), p. 93.

12. “An Inside Look at CALPERS’ Boardroom Report Card,” BusinessWeek (October 17, 1994).

13. See the special issue of BusinessWeek, Relationship Investing (March 15, 1993).

14. Steven M. H. Wallman, “The Proper Interpretation of Corporate Constituency Statutes,” Stetson Law Review (1991), Vol. XXI, pp. 163–196.

15. A central source of information on the progressive business movement is The New Leaders, a periodical published by John Renesch in San Francisco, California.

16. Kara Swisher, “Getting Down to the Business of Being Socially Responsible,” Washington Post (November 22, 1993).

17. From a scientific view, one might question which is cause and which is effect. Do human-oriented firms perform better, or is it that better-performing firms can afford to be human? It seems likely that both are true because cause and effect are circular. A human orientation improves performance, which then provides the resources to carry this approach further, and so on. See Troy Segal, “Putting Your Cash Where Your Conscious Is,” BusinessWeek (December 24, 1990).

18. Severyn Bruyn, The Social Economy (New York: Wiley, 1977).

19. The special issue on corporate control, BusinessWeek (May 18, 1987).

20. See Thomas Donaldson and Lee E. Preston, “The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, Implications,” Academy of Management Review (1994).

21. James O’Toole, “Go Good, Do Well,” California Management Review (Spring 1991).

22. Amitai Etzioni, The Spirit of Community (New York: Crown, 1993); Juanita Brown, “Corporation as Community,” in John Renesch (ed.), New Traditions in Business (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1992).

23. Russell Mitchell, “Managing by Values,” BusinessWeek (August 1, 1994).

24. Social evaluations using a comprehensive system of rigorous measurements, such as dollar equivalents, have been conducted by Clark Abt Associates and Atlantic Richfield Company. See Halal, The New Capitalism, p. 218.

25. Robert Greenleaf, Servant Leadership (New York: Paulist Press, 1977), and Peter Block, Stewardship (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1993).

26. “Tying Executive Pay to Social Responsibility,” Business Ethics (September/October 1995).

27. Michael Schrage, “To Reshape IBM, Gerstner Should Work from the Boardroom Down,” Washington Post (April 2, 1993).

28. Russell Ackoff, The Democratic Corporation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Christine Ferguson, “Hewlett-Packard’s Other Board,” Wall Street Journal (February 26, 1990).

29. Francis Moore Lappé and Paul Martin Du Bois, The Quickening of America: Rebuilding Our Nation, Remaking Our Lives (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994). Pat Barrentine (ed.), When the Canary Stops Singing: Women’s Perspectives on Transforming Business (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1994).

30. For instance, hospitals, banks, and public agencies are adopting similar concepts with great success. See Nancy Nichols, “Profits with a Purpose,” Harvard Business Review (November-December 1992); Peter Johnson, “How I turned a Critical Public into Useful Consultants,” Harvard Business Review (January-February 1993), Ronald Grzywinski; “The New Old-Fashioned Banking,” Harvard Business Review (May-June 1991), and Ronald Taub, Community Capitalism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 1994).