5

The Serving Enterprise

Relinquishing Our Grip on Self-Interest

Great battles are being joined in the marketplace today to decide which organizations will survive an onslaught of creative destruction. As rivals from around the world vie to meet growing demands for superior value and service, old allegiances to famous corporations of the past are being overthrown daily. Sears was replaced by Wal-Mart as America’s dominant retailer, the AT&T monopoly was shattered by MCI, RCA has been eclipsed by Sony, GM Chevrolets must now compete with Hondas and Toyotas, and even IBM is fighting for its life against Microsoft and Intel.

Despite business attempts to win the hearts and minds of fickle buyers, however, excellence remains an exception in America. Surveys find that roughly half the public thinks the value they receive is poor to fair, and a third thinks it is bad and getting worse. Swapping horror stories about terrible service and shoddy products remains a popular topic of conversation.1

A telling incident highlights the problem. On recent a trip to Russia, I had to fly on the Russian airline, Aeroflot. Although concerned about putting myself in the hands of a foreign flight crew flying outdated aircraft in a land where nothing works, I was pleasantly surprised to find that Russian flights were better because they departed and arrived punctually. Upon returning home, however, my American flights were so late that terminals were filled with irate passengers, hopelessly watching their connecting flights, meetings, waiting friends, and other carefully made plans disintegrate. The Department of Transportation reports that 25 percent of United States flights are late. Air travel in the United States has become a recurring nightmare, as passengers struggle through a bewildering maze of prices, connecting hubs, frequent delays, and lost baggage.2

And what are the airlines doing to solve the problem? The airline industry seems more concerned with promoting frequent-flyer programs to discourage customers from switching to competitors. There are no net benefits because the fortunate souls who patronize the system long enough to receive free flights are in fact being subsidized through the inflated fares paid by other patrons and travel expenses paid by their own employers. The IRS estimates that employers lose $4.5 billion in excessive air fare every year because employees take unnecessary business flights to earn frequent-flyer credits. Airlines themselves lose another $2 billion as free trips displace paying customers, in addition to the cost of maintaining this complex system.3 And because all major airlines offer the same programs now, any competitive advantage has been lost. In business terms, no value is added.

Despite the fact that almost no one benefits, the practice is spreading to hotel chains, car rental companies, and credit card companies because business cannot resist seducing buyers with the illusion of getting something free. This system may soon collapse like a chain letter, the way “Green Stamps” did a few decades ago. In 1994, the backlog of “miles” credited to frequent-flyers rose so high that airlines increased the number needed to get a free flight by 30 percent. Employers are organizing to eliminate the system, and passengers are suing airlines for discounting their earned miles.4

The urgent need to attract clients is understandable to anyone who has ever borne the responsibility to make a business succeed. But frequent-flyer programs are a symptom of how the Old Management often tries gimmicks to get clients rather than seriously improve service and value. In contrast, Southwest Airlines has become the most profitable firm in the industry by forsaking frills for the things that count: keeping fares below the competition, maintaining punctual schedules, offering direct flights, and encouraging employees to help passengers. One harried businessman was running to catch his Southwest flight as the plane pulled away from the gate; upon seeing the anguished look on the man’s face, the pilot returned to pick him up. “It broke every rule in the book,” said a Southwest manager, “But we congratulated the pilot on a job well done.”5 Now other airlines are emulating Southwest.

If it can be done, why are good service and genuine value so rare that they are celebrated as heroic? Why must customers struggle with poorly made products? Stores where you cannot find a helpful clerk? A failing educational system? Costly health care? Government bureaucracy? On the other side of the counter, why do managers tolerate such dismal performance? What can they do to regain the public’s trust? And how in the world can sellers figure out what buyers really want?

This chapter draws on insights into today’s changing social needs and examples of excellence to identify the principles of creative marketing in an Information Age. We will see that modern managers are challenged to focus on the needs of their clients rather than the firm—resulting in the “serving enterprise.” By forming a trusting relationship with customers, the New Management can be more profitable while also serving the genuine needs of these stakeholders who are central members of the corporate community.

FROM SELLING TO SERVING

The crux of the problem in marketing today is an outmoded focus on “selling.” While it seemed perfectly reasonable at one time, now this preoccupation with the interests of the enterprise is outmoded because it excludes the interests of clients. Theodore Leavitt calls it “marketing myopia.”

The Wasteful Noise of Advertising

The problem is illustrated by today’s barrage of advertisements. The average American is bombarded by 30,000 ads each day from TV, newspapers, and junk mail, all promoting yet another contrived bargain. Twenty million American homes are invaded during dinner each evening by 300,000 telemarketers. And ads are now appearing in schools, on shopping carts, and in every conceivable nook and cranny of life.6 The social effects of TV advertising are so disturbing that parents consider TV an “enemy” they must fight to raise healthy children (see Box 5.1). In our urgency to sell, we have reduced the miracle of television to a sewer of commercialism that sets a squalid moral tone for the nation.

The irony is that this stampede to seize the buyers’ attention is largely ineffectual; each message adds to the burgeoning maze of advertising noise, turning all this costly communication into an indistinguishable blur that deadens the senses. People have been so overhyped that they either ignore it, refuse to believe it, or just plain dislike it. Recent studies find that only a small percentage of advertising recovers its costs, and even these are effective only for a matter of months. Promotions do even worse because they encourage competitors to retaliate and they lower the company’s image.7

Special “sales” are a particular problem. At one time, a sale really meant a special situation that offered unusual value. Now the practice has been overused to the point that it is almost impossible to sell products at regular prices because people expect discounts. Thus, the public becomes confused over what constitutes a fair price, they distrust the seller, and merchants waste time and money on these futile exercises. Montgomery Ward spent 120 work days filling out 15,000 rain checks for one sale item that had run out of stock. The company’s CEO acknowledged that this approach “erodes your credibility.”8 Listen to how the president of the National Auto Dealers Association views the problem in the auto industry:

The public is tired of on-again, off-again rebate programs that confuse dealers and buyers. A child can figure out that the consumer pays the bill. So end the phony rebate and low interest-rates, establish a single, no-nonsense price and try something revolutionary: build good, reliable cars.9

From an economic view, this sell-at-any-cost approach is simply too crude to solve the complex job of serving an exploding array of highly differentiated, subtle social needs. Because buyers are left to find their way through misleading claims, Americans make suboptimal purchases that waste an estimated $1 trillion out of a $4 trillion economy every year.10 The predictable result is that people then look elsewhere for better value.

“Selling” also creates an adversarial relationship with the buyer. I am struck by the common assumption that the client is not a part of the organization, so the welfare of this impersonal figure is not of concern. Managers set the tone for this view if their main goal is making money, and this message is then conveyed to their organization. That’s why clerks often treat customers as an irritating inconvenience.11 A manager in the CIT study said, “Our philosophy seems to be ‘bill, bill, bill, so we can grow rich, rich, rich,’” and another admitted, “Our clients hate us.”

Consumerism Is the Other Side of Selling

While Americans are critical of shoddy goods and poor service, they also encourage the selling enterprise by responding so eagerly to the lure of quick material gratification. Americans spend 300 percent more time shopping than Europeans, and they consume roughly twice as much energy and resources.12 All this consumerism takes effort, so people are overworked, overwrought, and overweight from pursuing higher levels of consumption that are unrelated to personal happiness.13 Thus, consumerism is the other side of selling. They support one another.

The “selling/consumerism syndrome” is not solely the fault of managers or the public. To a large extent, this outmoded way of life persists as residual inertia from the dying forces that propelled the Industrial Age: mass production of simple consumer goods, a business focus on profit that excludes the public welfare, a throwaway culture, exploitation of what seemed a limitless environment, and the use of media to stimulate demand.

Most attempts to improve quality and service are palliative fixes because they fail to address today’s economic transition—our changing assumptions about the needs of society, the goals of the enterprise, and its relationship with clients.

The Rising Demand for Value and Quality of Life

Consider the average family. Typically, both husband and wife work today, so life is a struggle to clean and maintain their home, to take care of two cars, a few TVs and VCRs, several telephones, a home computer or two, and kitchen appliances. Then they must somehow attend to laundry and dry cleaning, shop for groceries, buy clothes and items for the home, prepare meals, entertain, juggle complex finances, and figure out their taxes. Simply finding affordable child care that can be trusted is an enormous challenge, let alone putting kids through college. To cope with these demands, many people are turning their cars into mobile living and working units, equipped with cellular phones, fax machines, portable PCs, and even microwave ovens.

These needs are being enshrined in a new set of social mores that focus on handling stress and using time productively. People today often compete with one another over their demanding responsibilities—the “busier than thou” syndrome. This is not limited to the harried middle class. Some of the wealthiest, most distinguished people in the world—Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and President Clinton—work so hard that they have to be forced to take vacations; they wear ordinary clothes and drive their own cars.14 Thorstein Veblen’s ethic of “conspicuous consumption” may have described the Industrial Age, but the Information Age is creating a new ethic that could be called “anxious achievement.”

Not only are social needs more complex, people are far more discriminating because they are better educated and they have access to a wealth of product information. Caught between stagnating incomes and rising costs, buyers look over worldwide competitors to select high-quality products, competitive prices stripped of unneeded frills or fancy brand names, and thoughtful service.15 Here’s how Fortune put it: “The customer isn’t king anymore. The customer is a dictator. Instead of choosing from what you have to offer, the new consumer tells you what he wants.”16

Some people will continue to seek material extravagance, of course, since that is one of the celebrated features of American life, and everyone will want to ride the new information superhighways. But a survey of 2,000 Americans found that “three-fourths say they’ve filled most if not all of their material needs.” Other polls show that 70 percent of Americans would like to lead simpler, more satisfying lives.17 People increasingly yearn for relief from stress, financial security, less crime and violence, recreation, clean air and water, meaningful social relations, and other complex social needs that are now the goals of human progress. Thus, the mission of business today must be nothing less than to raise the quality of life.

Reversing the Buyer-Seller Relationship

Advertising and other marketing tools will remain important, of course, but there are many ways to attract clients. Just as managers now understand they must create a “learning organization” to stay apace of change, they also need to create a “serving organization” that satisfies social needs more effectively.

Paul Hawken, an author and businessman, identified this change as the reversal of that old “centrifugal” marketing, which pushed products out of factories into the hands of passive customers. In its place, a “centripetal” role is emerging that draws a deeper understanding of the client’s needs and problems into the firm.18 John Scully, former CEO of Apple Computer, put it this way:

It used to be that marketing drove things. But marketing is really a mass-production-based concept. It’s about creating something that you can push out to the whole world. Today, everything is being customized, so it’s really being driven by the other side, by the customer.19

Wal-Mart’s humbling defeat of Kmart tells it all. In 1987, Kmart dominated the discount market with its 2,223 stores, bringing in annual sales of $26 billion. Confident in its strength, Kmart focused its strategy on traditional marketing, using national TV campaigns featuring glamorous women to bolster its “image.”

Meanwhile, Wal-Mart had half as many stores and was almost unknown. But instead of advertising, the company developed its now-famous logistics system. A satellite network was established to monitor sales nationwide, analyze these data to determine which products should be ordered for each store, and automatically replenish inventories by sending orders to 4,000 suppliers who were connected to Wal-Mart through computer systems. Wal-Mart was thereby able to optimize the choice of goods stocked at each store, minimize transportation and inventory costs, and pass these savings on in deep discounts. Three years later, Wal-Mart surpassed Kmart with sales of $33 billion. Sam Walton, the architect of Wal-Mart’s success, knew in his bones that Americans were hungry for value and service, and he provided it.20

PRINCIPLES OF THE SERVING ENTERPRISE

To meet this challenge, creative entrepreneurs are reorienting all phases in the life cycle of a product or service: high-tech marketing, truthful advertising, client participation, empowered employees focused on quality, accountability for customer satisfaction, and involved leadership.

High-Tech Marketing

As the Information Revolution drives the power of IT up and its cost down, a new form of high-tech marketing is emerging to transform buyer-seller relations. As Box 5.2 shows, electronic shopping services, computerized sales systems, automated product design, and much, much more promise to reduce distribution costs, make shopping convenient, and allow people to make wiser purchases. The prospects are so enormous that they cannot be addressed fully here, but a few examples illustrate the possibilities.

Two-thirds of U.S. companies operated toll-free information lines in 1993, and this network is spreading overseas as foreign manufacturers use it to tap into the American marketplace and vice versa. The GE Answer Center, for instance, receives three million calls each year from people asking about products, seeking advice, making complaints, requesting repairs, and other information that is then analyzed for marketing purposes.21

IT also is creating far more efficient distribution channels. On the input end, sellers are gaining access to unprecedented amounts of valuable information that allow them to understand their diverse markets and pinpoint the sale of products to meet highly specialized needs—“niche marketing.” On the output end, buyers are gaining an equally valuable source of information that evaluates various products to allow better choices—“precision shopping.”

Not only are distribution channels becoming smarter, but they are also becoming shorter as middlemen are eliminated. Dell Computer became a powerful competitor to IBM when Michael Dell realized he could sell PCs through the mail—“just-in-time retailing.”22 Without the need for manufacturing shops, warehouses, retail stores, and salespeople, the cost of a Dell computer drastically undercut IBM to launch the PC clone industry.23

At the advanced end of the IT spectrum, interactive video shopping should enter the mainstream in the late 1990s.24 Even now, the Home Shopping Network offers the wares of Nordstrom, Bloomingdale’s, J. C. Penney, and other retail chains to 60 million homes that made up a $3 billion market as of 1993.25 TV shows, newspapers, and other media may soon include interactive advertisements that carry the shopper into a “virtual store” where products can be examined, prices determined, and orders placed. Peapod, an electronic grocery service, allows clients to create a “virtual supermarket” customized to their unique needs by setting up standard shopping lists for reordering and comparing prices at all local stores.

Truthful, Useful Customer Relations

It may appear hopelessly naive in today’s world of hard-selling, glitzy ads, but many fine companies owe their lasting success to the opposite approach: advertising and customer relations that tell the truth. L. L. Bean, Hershey Foods, Toyota, Johnson & Johnson, and countless other examples of highly successful organizations demonstrate that business can be conducted honorably, and it is usually more profitable.

In 1993 Saturn had to recall all the cars it had ever sold. Rather than proffering the typical evasions and half-truths that are normal in the auto industry, Saturn immediately announced the full details of the problem and its proposed solution. The president of the company, Richard (Skip) LeFauve, appeared on television to personally explain the situation, apologize, and tell customers to contact their dealer to arrange a free retrofit, or the company would call them. This candid approach turned a potential disaster into proof of Saturn’s claim to a new form of management, and thereby increased public’s trust in the company. (See Box 5.3.)

Saturn, Nordstrom, Toys “R” Us, Wal-Mart, Procter & Gamble (P&G), and other companies exemplify the use of “everyday low prices” instead of contrived sales or promotions. A P&G manager said: “We want our brands to be a good value every time they are bought rather than a bargain every now and then. Our customers appreciate that”; and a Continental Airlines manager said: “Customers are all under the same constraints of price and time, which is why simplicity and consistency have great appeal.”26

Pursuing a policy of truthful client relations is not simply a moral issue but a more powerful form of marketing. Honesty builds lasting patronage based on the confidence that the company is committed to providing value. As shown in Box 5.4, the Body Shop has enjoyed remarkable growth, even though it does no advertising; it does not even have a marketing department. By offering healthful, inexpensive cosmetics while protecting nature, the company has ignited a roaring demand among satisfied customers—who then do the marketing for the firm by telling their friends. Paul Hawken described the merits of truthful customer relations:

There is one mistake no entrepreneur can afford to make—misleading customers. They stop buying. In the tawdry world of braggadocios, the truth rings with clarity. It changes the signal-to-noise ratio. The noise is the $95 billion spent on advertising. The signal is the clear tone of honesty that comes through as compellingly as the siren of an ambulance.27

Client Participation

Studies have long shown that most successful new products are developed in response to suggestions by customers. Rather than studying people’s needs through market surveys, progressive firms actively involve their clients in the design process. “I think the current notion of market research is going to be completely overturned,” said the vice president of a marketing firm.28 This is especially true for the new product markets and customers that make up the frontier of the emerging knowledge society. “You can’t market research something that doesn’t exist,” said Peter Drucker.

Companies are using this concept in numerous ways to achieve excellence. GE, for example, asks its design engineers to work with customers in defining an ideal appliance. Hewlett-Packard invites buyers of its products to give presentations to engineers and managers, pointing out problems they encounter and suggesting improvements. Fisher-Price created a nursery in its corporate headquarters where parents can bring children to try out new toys; the waiting list runs into the thousands. (See Box 5.5 for more examples.)

This is just a trickle of what may become a flood of “do-it-yourself” marketing, as buyers shun the services of building contractors, repair people, retailers, and other traditional providers. Home Depot offers repair clinics that allow customers to create value by replacing contractors. Estimates suggest that the amount of work devoted to home projects is equivalent to 40 percent of the GDP. The CEO of Price Club explained why his no-frills bulk sales are so successful: “[All companies] say they provide great service, but self-service is the best kind of service.”29

There is also a need to involve clients at the policy level by creating consumer advisory panels of typical customers who advise organizations. A more powerful approach is to appoint clients or consumer advocates to the corporate board, and it is puzzling why more corporations have not done so. If we really hope to manage organizations to serve clients, what better place to start?

The usual objection is that consumer advocates are likely to be critical, which would disrupt the harmony of the board. But perhaps this “harmony” should be disturbed to urge unresponsive firms into action. Our critics are the people we should pay closest attention to because they are keenly aware of our weaknesses. That’s why they infuriate us so much. A sound enterprise listens carefully to criticism because it is valuable feedback and a source of energy that drives creative change. Most people are reluctant to complain, so brave managers hire firms like “Feedback Plus,” who use professional shoppers to evaluate how well their customers are treated. “Stores that score high on our shopping service have the best sales,” claims a vice president of Feedback Plus.30

But it is possible to become too close to customers. People often lack the imagination to envision major changes in lifestyles, leading companies to mimic present trends rather than radically carve out the markets of the future. The microwave oven, minivan, fax, and VCRs all bored prospective customers until they were available. Conversely, customers insisted they were mad about the New Coke, picturephones, and other products that fizzled. So it is essential to keep the buyer-seller relationship in perspective. Client-driven marketing is more than simply doing whatever clients say; it is a two-way exchange in which companies must maintain faith in their judgment about how to best serve new needs.31

The possibilities are endless, but they are all variations on a central principle of the new marketing philosophy: companies are more likely to design useful, economically successful products by making the client an active partner in the enterprise.

The Quality-and-Service Revolution

TQM has assumed mythical proportions because it is part of a “quality-and-service revolution” that is moving from business to government and all other institutions. Contrary to the prevailing prior belief that quality is “nice but costly,” sound management reduces costs by building quality into superior designs, thereby eliminating the need for rework, avoiding customer returns and lost business, and permitting economies of scale.

Quality is often shrouded in complex terms, but the key factors are disarmingly simple. We saw in Chapter 2 how crucial enterprise is to making TQM work. Home Depot (Box 5.6) and Saturn show how successful firms form self-directed teams charged with the responsibility of serving clients through continuous improvement processes.

Beyond today’s struggle to improve quality, a cornucopia of near-perfect customized goods should soon flow out of automated factories, as we will see in the next chapter. A good example of this “mass customization” is the way Dell Computer builds 90 percent of its PCs to order and delivers them in two days.32

Employee Rewards Linked to Client Satisfaction

It is also necessary to measure how well these goals are accomplished. Sales and profit are important, but they focus on the needs of the organization rather than the needs of the client. Financial performance is the result of client satisfaction, so the primary focus should be on evaluating this crucial factor.33 One manager in the CIT survey expressed it well: “Customer feedback is the key to sound business; revenues are a lagging indicator.” Sears was the subject of national scorn in 1992 because workers in its auto repair shops, under pressure to increase sales, were gouging clients; now the company is using client satisfaction evaluations.

McDonald’s and L. L. Bean use periodic surveys to evaluate customer satisfaction. Marriott and Western Union make unannounced inspections of outlets. Giant Foods and Avis have employees and executives patronize their stores incognito to observe how they are treated. Ford invites car owners to meet engineers and dealers to discuss problems with their cars. State Farm and Toyota measure customer “loyalty” and “retention rates.”34

An old management axiom that holds that organizations get what they reward, so it is also essential to base employee pay at least partly on evaluations of client satisfaction. GTE’s system allocates 35 percent of employee and manager pay in accordance with client satisfaction ratings. Xerox bases 30 percent on client surveys. Chrysler has begun to pay bonuses to its dealers with high client satisfaction scores.35

As some of these examples suggest, it is best to reward an entire team or business unit, rather than individuals. Group rewards are easier to manage and they promote unit cohesion. We will say more about the management of teams in Chapter 6.

Involved Leadership

Organizations that deliver products of lasting value with genuine service are usually blessed with the leadership needed to bring a serving enterprise to life. Only executives can provide the vision and personal example that focuses a large organization on serving its clients. Home Depot would not be the same without Bernard Marcus and Arthur Blank. The Body Shop is inspired by Anita Roddick. Sam Walton created Wal-Mart.

Xerox executives spend one day each month taking complaints from customers. The president of Hyatt Hotels occasionally works as a bellhop. Skip LeFauve invited all 700,000 Saturn owners to attend a barbecue at its plant; 28,000 people showed up, making it the “Woodstock” of the auto industry. “It’s a good way to say thank you and foster a closer relationship,” said Saturn’s marketing manager.

Harley-Davidson has organized 700 Harley Owners Groups (HOG Clubs) that hold an annual rally; the highlight occurs when the company’s CEO, Rich Teerlink, roars in on his own gleaming top-of-the-line Harley. When Teerlink first started this approach, the company was almost bankrupt. The stock has since gone from $1.20 per share to $26, and buyers have to wait years to get a Harley.

Herb Kelleher, the CEO of Southwest Airlines, is a clowning genius who sets such a friendly tone with clients that Southwest personnel often joke mercilessly with passengers. One flight heard this announcement over the PA system: “Good morning ladies and gentlemen. If you wish to smoke, please go to our lounge on the wing where you can enjoy our feature film, Gone with the Wind.”36

A small Oregon restaurant chain highlights the importance of leadership by illustrating all of the principles discussed in this chapter. After struggling to improve service, the CEO established a policy that all patrons must enjoy a pleasant dining experience. Just as Avis claims “We Try Harder” and Federal Express promises “Absolutely, Positively, Overnight,” this company’s primary goal was “Your Enjoyment Guaranteed. Always.” As the CEO put it, “My company exists to make other people happy.”

He then changed operations to ensure that this guarantee was fulfilled. Employees were told to do anything necessary to satisfy a customer—offer free drinks, meals, or special attention—and they were trained to do so effectively. Customer satisfaction was evaluated using a monthly phone survey and by measuring the number of complaints, and the total cost of resolving them was tallied. The company found that many customers had been unhappy but reluctant to complain, so they had simply voted with their feet and gone elsewhere. Under the new guarantee, the costs of correcting complaints rose, making the problems that were formerly hidden visible.

Where most managers would be aghast at seeing costs rise, this CEO recognized that such costs are symptoms of deeper problems, and as such are valuable information. As the CEO said: “Every dollar paid out is a signal that the company must change.” As these system failures were found and corrected, costs dropped to modest levels, clients became delighted at the service, employees took pleasure in their work and were better paid, sales increased, and profits doubled.37

MAKING THE CLIENT A PARTNER

But why should we go through all this trouble, cost, risk, and personal discomfort to satisfy demanding people? L. L. Bean worked hard to become customer-focused and was rewarded by a wave of merchandise returns valued at $82 million. Let’s face it. Many clients are impossible to satisfy at all, much less at a profit. The CEO of Southwest Airlines writes to customers who abuse employees, asking them to fly on another airline.

It’s also hard to change the habits of people who have raised the narcissistic pursuit of self-interest to an art form. Admonitions to serve clients have to fight the influence of an American culture that urges employees to “Look Out for No 1.” The reality is that genuine service requires discipline and hard work. A field of study has emerged to understand the rigors of “emotional labor” performed by service personnel, and an industry has sprung up to train employees in dealing with quarrelsome people. Flight attendants must be friendly, nurses are expected to show sympathy, and teachers must be supportive, even when they may feel upset.38

And how can employees please customers when they must struggle against bureaucracy, authoritarian supervisors, and other common management problems that hinder service and quality? The serving enterprise is a part of the New Management, so it is necessary to change the entire management system, as other chapters will show.

Seeing Problems as Opportunities

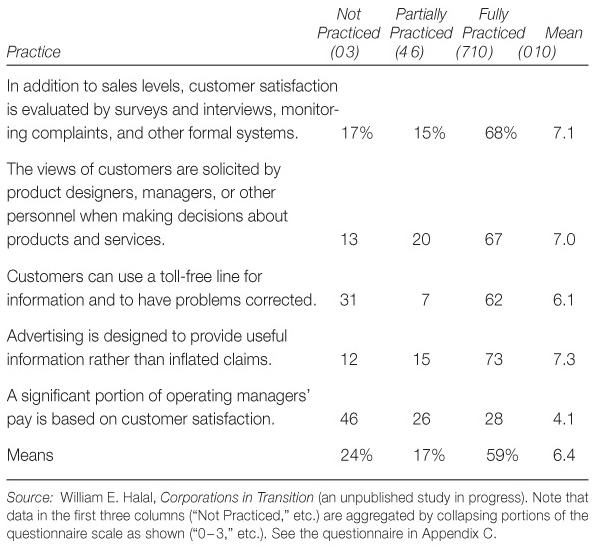

There is little choice but to overcome such objections because they now conflict with reality. Managers have been told endlessly that they must be primarily concerned with selling and financial goals, yet that belief is being challenged as a new breed of clients, complex social problems, and global competitors demand a shift to serving the needs of the client. Table 5.1 shows that these concepts are now widely practiced.

Each lost customer takes two to three others away after complaining to an average of nine friends, and it costs five times as much to recruit a new customer as to retain an existing one.39 Each lost client costs an automaker $400,000 over a lifetime and a grocery store $25,000 every five years. Improving the customer retention rate by 2 percent will typically increase profits 10 percent. Driven by such economic realities, an executive described the reaction: “It’s not like we sat here and said, ‘Let’s change the way we sell.’ We had no choice.”40

This enlightened form of marketing also offers important long-term benefits. A working partnership with clients better positions the organization to understand complex new social needs in order to convert these problems into business opportunities.

The auto industry, for instance, could enter a fresh cycle of growth by finding a better way to satisfy the public’s travel needs. The Japanese made great inroads into American markets by realizing that a car is more than a stylish piece of machinery. Rather, they viewed a car as a transportation system involving fuel efficiency, maintenance, safety, and insurance—all of which have become vitally important to car owners. An average auto cost about $17,000 in 1993, but these additional factors cost another $40,000 over a typical product life of ten years, making the ownership of an automobile a major investment of roughly $60,000.41

The amount of money spent on auto repair and maintenance alone is about as great as that spent on the purchase of new vehicles. Roughly two-thirds of this sum is wasted because of improper diagnosis, poor workmanship, and fraud.42 Businesspeople should see that this problem is actually an opportunity crying out for a solution. By learning how to maintain autos better, dealers could save customers thousands of dollars per year while minimizing the time and aggravation involved in car ownership—creating a virgin market that roughly equals the entire new car market. Similar opportunities are possible in reducing the fuel, safety, and insurance costs of this system.

As Hamel and Prahalad point out, all industries must redefine their mission to meet the needs of tomorrow.43 Sweden now produces 95 percent of its homes in factories, and the Japanese are moving toward automated construction of high-quality housing modules that can be assembled quickly into an infinite variety of pleasing, inexpensive homes. Will the American building industry suffer a replay of the Japanese invasion of U.S. auto markets? Which companies will develop the first reasonably priced, convenient telecomputer? Automatic language translation? Mechanical hearts and other vital organs? Personal tutoring systems? Optical computers? And an endless array of other revolutionary new products that will make today’s microwave ovens and PCs look primitive?

Other institutions will be forced to surmount similar challenges in the years ahead. Medicine must move beyond curing illness to develop convenient, inexpensive ways to help each individual find a healthy style of living. Education must use IT to make learning a continual part of everyday life in a fast-paced technological age. And government must regulate this entire system in a way that assists people while minimizing taxes and regulations. These goals constitute a vast frontier of progress precisely because the world is swamped with so many difficult social problems that can be converted into opportunities. A few years ago I noticed a small sign in a shop window that quietly announced the secret of sound business that successful entrepreneurs have always known:

Business success is not for the greedy. On the contrary, lasting success results from giving more and charging less. The possibilities are infinite.

Yielding Self-Interest

This discussion of modern marketing leads to four main conclusions:

1. A global economy of fierce competition and demanding clients requires that customers’ interests become paramount.

2. Appeals through “selling” have become largely ineffectual because they merely add to the noise of advertising.

3. Managers must create a “serving enterprise” that uses information technology and involved employees to form a working partnership with clients that serves their genuine needs.

4. This concept of a serving enterprise can help managers reorient their organizations so as to convert today’s social problems into profitable opportunities for improving the quality of life.

Although economics has been called “the dismal science” because it has generally assumed scarcity, economic life can be abundant when approached with faith in the creative nature of a bountiful world. The key to this pivotal change is to see that a serving enterprise combines the two powerful forces of internal markets and corporate community, as we noted in Chapter 4. Inventive managers organize operations into entrepreneurial teams that serve clients better, thereby uniting financial and social goals. By giving thoughtful consideration to others, it may be returned to us manyfold. “Cast your bread upon the waters,” as the Bible expressed it.

Putting the welfare of clients foremost does not mean managers and employees must become self-sacrificing martyrs, although they do have to give of themselves. As we stressed in Chapter 3, the idea is to develop a working relationship based on mutual rights and responsibilities. Like any partnership, both partners have to give, including the client. Part of the New Management would be to help clients learn how to use the product or service wisely, to hold reasonable expectations, and seek resolution of problems before withdrawing patronage or pressing a lawsuit.

Individuals and organizations must handle these issues in their own ways, and many will opt for conventional methods. Despite the growth of a soft sales approach, for instance, some car dealers continue to thrive on overstated ads and sales pressure. The fact is that many buyers are reluctant to give up the thrill of haggling over prices.44 We are reminded again that the New Management cannot be used as doctrine if it hopes to meet the diverse needs facing organizations.

Because a diversity of approaches is possible, tough choices must be made that hinge on our personal values and willingness to change. Do we really have to accept this challenge of yielding our self-interest? I know that I have trouble subjugating my interests. If it is true that serving others is more effective, what prevents us from doing it? What would we give up? What would we gain? What will happen if we do not change?

I must admit that I do not have good answers to these questions, but I do know that the trends noted above are going to severely test us all during the difficult years ahead.

Notes

1. “Pul-eeze! Will Somebody Help Me?” Time (February 2, 1987). Amanda Bennett, “Making the Grade with the Customer,” Wall Street Journal (November 12, 1990).

2. “Is Herb Kelleher America’s Best CEO?” Fortune (May 2, 1994).

3. Rex Toh et al., “Frequent-Flier Games: The Problem of Employee Abuse,” The Executive (February 1993).

4. “15 Firms Target Workers’ Frequent-Flyer Awards,” Washington Post (May 9, 1994). “Frequent Flyer Changes Rile Passengers,” Washington Post (February 2, 1995). For a good analysis see Jeff Blyskal, “The Frequent Flyer Fallacy,” Worth (May 1994).

5. “20 Companies on a Roll,” Fortune (Autumn/Winter 1995).

6. Don Oldenburg, “Don’t Just Hang Up,” Washington Post (January 14, 1993).

7. Magid M. Abraham and Leonard M. Lodish, “Getting the Most Out of Advertising and Promotion,” Harvard Business Review (May-June 1990), pp. 50–60; John Philip Jones, “The Double Jeopardy of Sales Promotions,” Harvard Business Review (September-October 1990).

8. Paul Farhi, “The Everlasting Sale,” Washington Post (June 20, 1993). Francine Schwadel, “The ‘Sale’ Is Fading as a Retailing Tactic,” Wall Street Journal (March 1, 1989).

9. In “Letters to the Editor,” BusinessWeek (July 3, 1989).

10. James H. Snider, “Consumers in the Information Age,” The Futurist (January-February 1993).

11. A survey of 260 marketing executives found that “profitability” was rated as their highest priority, “quality” was third, “better communications with customers” was fifth, and “customer satisfaction” was not mentioned. “Marketing Priorities,” Research Bulletin No. 205 (New York: The Conference Board, 1987).

12. See James Patterson and Peter Kim, The Day America Told the Truth: What People Really Believe About Everything That Really Matters (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1992).

13. Juliet Schor, The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

14. Richard Todd, “Po’ Boys on Parade,” Worth (September 1993).

15. See the special issue Value Marketing, BusinessWeek (November 11, 1991).

16. Meet the New Consumer, special issue of Fortune (Autumn/Winter 1993), pp. 6–7.

17. “Most Consumers Shun Luxuries,” Wall Street Journal (September 19, 1989). Duane Elgin, Voluntary Simplicity (New York: Morrow, 1993).

18. Paul Hawken, “Truth or Consequences,” Inc. (August 1987).

19. Quoted from Rich Karlgaard, “An Interview with John Scully,” Forbes (December 1992).

20. Christina Duff and Bob Ortega, “How Wal-Mart Outdid a Once-Touted Kmart,” Wall Street Journal (March 21, 1995).

21. Conference Board Monthly Briefings (February 1987).

22. Gretchen Morgenson, “The Fall of the Mall,” Forbes (May 24, 1993).

23. Alice LaPlante, “It’s Wired Willy Loman,” Forbes ASAP (June 1994).

24. Patricia Sellers, “The Best Way to Reach Your Buyers,” Fortune (Autumn/Winter 1993).

25. “Retailing Will Never Be the Same,” BusinessWeek (July 26, 1993).

26. Patricia Sellers, “Keeping the Customers You Already Have,” and Rahul Jacob, “Beyond Quality & Value,” both in Fortune (Autumn/Winter 1993).

27. Hawken, “Truth or Consequences.”

28. Michael Schrage, “Customers May Be Your Best Collaborators,” Wall Street Journal (February 27, 1989); “The ‘Bloodbath’ in Market Research,” BusinessWeek (February 11, 1991).

29. Ronald Henkoff, “Why Every Red-Blooded Consumer Owns a Truck,” Fortune (May 29, 1995).

30. Kevin Helliker, “Smile: That Cranky Shopper May Be a Store Spy,” Wall Street Journal (November 30, 1994).

31. Justin Martin, “Ignore Your Customer,” Fortune (May 1, 1995).

32. B. Joseph Pine et al., “Making Mass Customization Work,” Harvard Business Review (September-October 1993).

33. There is controversy over this point. Some authorities claim that client satisfaction does not correlate well with retention, so it important to distinguish client satisfaction from loyalty. See Frederick Reichheld, “Loyalty-Based Management,” Harvard Business Review (March-April 1993), and Leonard Berry et al., “Improving Service Quality,” Academy of Management Executive (May 1994).

34. “King Customer,” BusinessWeek (March 12, 1990). Rahul Jacob, “Why Some Customers Are More Equal than Others,” Fortune (September 19, 1994).

35. These examples are noted in “Smart Selling,” BusinessWeek (August 3, 1992); “King Customer,” BusinessWeek (March 12, 1990).

36. Kenneth Labich, “Is Herb Kelleher America’s Best CEO?” Fortune (May 2, 1994).

37. Timothy W. Firnstahl, “My Employees Are My Service Guarantee,” Harvard Business Review (July-August 1989).

38. See Arlie Hochschild, The Managed Heart (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983), and Blake Ashforth and Ronald Humphrey, “Emotional Labor in Service Roles,” Academy of Management Review (January 1993), pp. 88–115.

39. J. C. Szabo, “Service = Survival,” Nation’s Business (March 1989).

40. “Smart Selling,” BusinessWeek (August 3, 1992), p. 47. Emily Thornton, “Revolution in Japanese Retailing,” Fortune (February 7, 1994).

41. Halal, The New Capitalism (New York: Wiley, 1986), Ch. 3.

42. See Halal, The New Capitalism, Ch. 3.

43. Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad, Competing for the Future (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 1994).

44. Douglas Lavin, “Youwannadeal?” Wall Street Journal (July 8, 1994).