CHAPTER 9

Crafting a Tangible Vision

When you work in a small business, such as a start-up, you can get everyone to play off the same sheet of music more easily. The larger your organization, however, the greater the challenge of understanding the end-to-end experiences you want to enable and why. Hierarchy, functional silos, and distributed teams create communication and collaboration barriers. Strategy is distributed in slides with terse bullet points that get interpreted in multiple ways. The vision for the end-to-end experience is lost in a sea of business objectives, channel priorities, and operational requirements. The result: painful dissonance when the dream was a beautifully orchestrated experience.

This chapter is about working with others to craft a tangible vision for your product or service–a North Star. These approaches will help your organization embrace a shared destiny and collaboratively create the conditions for better end-to-end experiences.

The Importance of Intent

The use of the word intent has increased dramatically in the halls of most large corporations. You may have intent owners or leaders in your organization, or intent statements as part of your strategy and execution process. Intent is an important concept to understand and align with to get things done, especially with the complexity inherent to orchestrating end-to-end experiences.

Strategic Intent and Lean Management

In the late 1980s, management consultants Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad studied the reasons Japanese companies were eclipsing their Western competitors in innovation and business outcomes. They coined the term “strategic intent” to codify how these organizations focused their employees on the same target. Instead of a generic mission statement, there was a simple, inspiring rallying cry. Yearly strategic planning was replaced with pairing near-term goals with the freedom for employees to determine the steps to achieve them.1 Hamel and Prahalad argued that these practices motivated employees to find inventive ways of creating great outcomes despite relatively scarce resources.

In the decades since, many corporations have begun to embrace the concepts of strategic intent, as well as its close sibling, lean management. If you work in a medium- to large-sized organization, you likely see the tentacles of lean making their way into every nook and cranny—small, cross-functional teams, kanban boards, value stream mapping, SMART goals, and so on. The uniting philosophy behind these tactics is to empower small teams to deliver upon strategic intent through extreme focus and collaboration, as well as to streamline or remove processes that don’t directly result in customer value. In this way, lean management is one of the primary means to drive to the destination evoked in the strategic intent.

Commander’s Intent and Agile

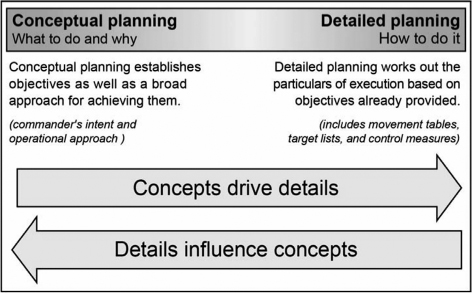

Another strain of intent common in organizations derives from the military: commander’s intent. In this context, intent is a commander’s concise statement for the purpose and desired end state of a military operation. Well-crafted intent “must be understood two echelons below the issuing commander” and “focus subordinates on what has to be accomplished in order to achieve success.”2 While this sounds top down, commander’s intent sets the context for a dialogue between those responsible for conceptual approaches and those crafting detailed execution plans (see Figure 9.1).

FIGURE 9.1

The relationship between intent and execution from the U.S. Army’s The Operations Process (ADRP 5-0) field guide.3

As a philosophy, commander’s intent reflects a move away from command and control toward crafting a clear vision and empowering semi-autonomous action. It’s no surprise that this type of intent would inspire other organizations grappling with increased complexities and rapid change. You see these dynamics in the adoption of agile approaches in more established organizations. In agile development, for example, a product owner provides the commander’s intent to support agile teams, who then have the latitude to determine how best to define and sequence tasks to reach the objective.

Ambiguous Intent and Experience Design

Organizations should strive to inspire employees to stretch while providing them with more agency to achieve important strategic objectives. Teams should look for ways to work smartly and flexibly, not follow rigid, unchangeable operating procedures. These approaches, on paper, embrace human ingenuity and the complexity of the problems that they are trying to solve.

In practice, however, intent applied within the context of product and service definition runs into many issues if your objective is to have effective end-to-end experiences. These include the following:

• Words are ambiguous: Intent is communicated through words, often in just a few concise points. People across the organization may read or hear the same thing, but each may envision a slightly or dramatically different solution or experience to each the business objectives.

• Just the facts: Success is defined as business results (more customers, greater profits, or increased NPS) and a list of features (mobile check-in, personalized recommendations, or self-service help) without a vision for the customer experience and the role of different channels and touchpoints.

• Incomplete value: The benefits to the business are clear, but the value to customers and other stakeholders is absent or uninformed.

• Cascading communication: Even in relatively flat organizations, communication from leadership to employees or from strategy to execution loses important nuances as the vision is filtered through the lens of functional leaders and managers operating in organizational silos.

• Domains of control: In most organizations, no one owns the end-to-end experience; they own the brand, channels, touchpoints, processes, and technologies. These leaders are measured on the performance of their piece puzzle, not higher-order metrics for the quality of customer journeys. In this context, ambiguous visions are easy to ignore, pay lip service to, or de-prioritize.

• Fire and forget: Drafting an intent statement or a strategy document, no matter how well communicated, is just the beginning of steering an organization toward better end-to-end experiences. Increasing your chance for success requires ongoing communication and collaboration, as well as adaptability, because execution reveals deficiencies in even the best of strategies.

Overcoming these deficiencies requires augmenting intent with a clear articulation of future customer experiences. In other words, intent needs a tangible vision.

Defining Your Vision

A tangible vision communicates examples of desired product or service experiences, as well as how the organization might achieve this end state over time. Unlike intent statements and requirements, it shows—largely from the customer’s perspective—how a well-designed and orchestrated system of touchpoints can create better outcomes. As a process and a set of artifacts, it helps you and colleagues do the following:

• Clearly frame what value will be created for customers, your business, and other stakeholders through better orchestrating of end-to-end experiences.

• Help each functional group look outside of their functional sphere and see how they fit in the greater whole.

• Show where channels, features, touchpoints, capabilities, and moments must integrate to result in holistic experiences.

• Maintain empathy for customers as teams across the organization make critical decisions in designing the channels and touchpoints for which they are directly responsible.

• Act as a reference point for future action, guiding decisions that should align with intended experiential outcomes for customers.

• In keeping with the spirit of intent, help unite and empower internal stakeholders to play their role in making the future a reality.

A handy analogy for a tangible vision is the North Star, Polaris. Also known as the lodestar (“guiding star” in Old English), the North Star is used in celestial navigation because it lies nearly in a direct line with the North Pole, and thus, being at the top of the Earth’s rotation, appears fixed as other stars appear to rotate around it. It’s important to note that the North Star is not a destination; it’s used as a constant against which to navigate toward a destination.

As with intent, defining a North Star for product and service experiences doesn’t mean figuring out every detail. Your North Star should guide—not prescribe—methods of execution. It must frame for the organization qualitatively the types of experiences that will meet customer needs moment by moment, channel by channel, and journey by journey. A North Star provides enough detail to inform and align downstream channel and touchpoint design, but not so much detail that others feel they are simply painting within predefined lines.

It is important to continue to collaborate with others across the organization as you formalize your strategy and hang your North Star in the sky for others to follow. Hopefully, you have been working with and communicating to a diverse, cross-disciplinary team all along. Why? You are instigating a paradigm change that many organizations desire but struggle to make happen.

Previously, a call center worried just about the experience that customers had when calling. It was relatively easy with that function to rally around an operating model based on customer service principles. Similarly, the web team focused on the website experience, the mobile group on mobile, and on and on. Since it is unlikely one person owns an entire journey or end-to-end experience, buy-in from leaders and their teams across the organization is critical for your North Star to cut through the corporate din of competing visions and objectives.

Your tangible vision is an important bridge, from what is to what could be. It sets the table for intentional orchestration of the customer experience and invites the organization to take their seat. The planks of this bridge are:

• Stories from the future: Future-state customer narratives communicated with enough clarity to socialize and be understood across an organization.

• Service blueprints: A prototype of how key customer pathways could be delivered operationally in alignment with your experience principles.

• Capability descriptions and future-state touchpoint inventory: Details of discrete capabilities (aka features) that are critical for delivering upon the value proposition in and across key customer moments, as well as a framework defining touchpoints in all channels envisioned to support the customer experience.

Your experience principles, opportunity maps, and other outputs from your strategy work will also help people understand and buy into your vision. As you will see, they and the overall value proposition should be woven into your vision. Let’s now look at these three planks in detail.

Stories from the Future

You have probably noticed that narrative plays an important role in orchestrating experiences Finding patterns in the stories you collected from customers uncovers the gap between your current product or service experience and what your customers need. Repeating and sharing those stories builds empathy in cross-functional teams. Storytelling and improvisation provide a customer-centered form to generate and create new ideas.

Therefore, it should be no surprise that stories are an effective vehicle for recommending what customers should experience in the future. First-person narratives, told from the perspective of your customers, show the interactions and outcomes that your organization should rally behind. These stories illustrate the specific roles channels and touchpoints should play moment by moment. They also provide a tangible example of how your product or service will fit in your customer’s context. This holistic storytelling is critical to ensure that colleagues understand your vision and its efficacy. As executive coach Harrison Monarth put best, “A story can go where quantitative analysis cannot: our hearts.”4

How does one create and communicate these narratives—these stories from the future? The approaches described in Chapter 8, “Generating and Evaluating Ideas,” apply here: show the experience from the customer’s perspective; visualize, don’t describe; explore the experience from different vantage points; and reinforce context. In terms of form, storyboards work well to communicate your stories from the future (and are relatively low effort to produce). Other formats—such as videos, posters, and narrated storyboards—are also very effective. Often, combinations of these forms work well for communicating to various audiences and in different contexts. Regardless, what you decide to place into your stories should be traceable back to the insights and experience principles.

BUILDING ALIGNMENT THROUGH STORYTELLING

Stories are an important tool to build alignment and focus. I’ve often seen how even low-fidelity sketches of customer narratives get across important points of functional coordination that requirements or program plans never do. Stories are also easily repeated and socialized, which helps spread and maintain customer empathy.

Consider the following guidelines in order to create compelling and effectives stories from the future.

• Cocreate your stories. As mentioned earlier, define your stories as a cross-functional team. (This should flow out of your idea prioritization.) Your goal is to show how an experience harmonizes across channels and touchpoints, so it’s critical to keep collaboration strong and get the buy-in of their relative functions (see Figure 9.2). You should also put these stories in front of your customers to get feedback and improve your conceptual stories.

COURTESY OF RICHLAND LIBRARY

FIGURE 9.2

Creating stories from the future collaboratively builds organizational trust and buy-in for your intent.

• Provide a range of stories. In addition to showing future experiences from a customer’s perspective, make sure that you share stories of different kinds of people in different situations. However, your goal is not to create dozens of potential scenarios. Instead, include a set of stories that establishes a good understanding of the range of key experiences, as well as the flexibility that will be necessary to be built into channels and touchpoints to accommodate the varying needs and contexts of your customers.

• Emphasize emotion. Your stories should not merely focus on future actions and interactions, but also the emotional context. They must communicate the human dimension of your vision and reflect how future experiences will foster customer emotions. Your stories must also depict the critical moments and interactions in which your product or service will have a positive emotional impact.

• Be specific, but focus detail where it matters most. You want others to believe your stories from the future. Use the stories and insights from your design research to bring richness and realism to them. However, avoid granular details that paint too fine of a picture of features and touchpoints. Remember, you want to leave plenty of room for others to design these details while adhering to the greater system conveyed in your tangible vision.

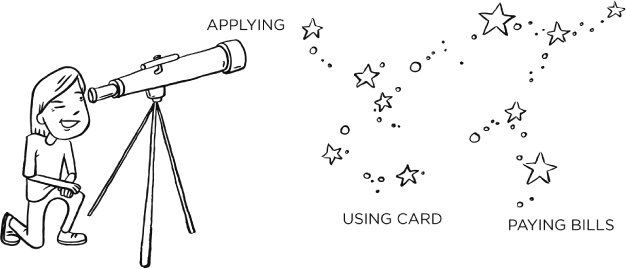

• Show different solutions working in tandem. Focus your storytelling on showing how a system of touchpoints can create the pathways that customers will follow in the future. Communicate how consistent, continuous experiences will result in greater value to both customers and the business. In this sense, you are like an astronomer unveiling the connections that will transform individual stars into a more powerful constellation (see Figure 9.3).

• Mind your time horizon. Each story should paint a picture of how intent manifests as valuable experiences in the future. How far into the future? It depends upon your context. You may be helping others understand experiences that will result from optimization work over the next six months, or your stories may put a stake in the ground for customer stories that may play two to three years into the future. In the latter case, you can create stories that show the evolution of the experience at different points to inform near-term to mid-term work (see, “Determining Your Evolutionary Path” later in this chapter).

FIGURE 9.3

Rather than a North Star for each major channel or touchpoint, your objective is to show the constellations that unite them in service to the journeys of customers.

• Show clear connections to what and why. Include additional details and annotations to help others understand why these stories are important and what it will take to bring them to life. Effective approaches include noting your experience principles, showing which opportunities are being addressed by moment, and listing the capabilities required to enable each moment to happen (see Figure 9.4). Also, consider explicitly calling out the value created for different stakeholders by story or by moment.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 9.4

In this example, opportunities and experience principles are correlated with each key moment of a retail journey.

Airbnb Frames Its Intent Through Story

Service Blueprints

Stories from the future depict key examples of holistic customer experiences, but they do not tell the whole story of your vision. To make your intent clear and actionable, you need to articulate how new or improved operational components—people, processes, and technologies—can form an effective end-to-end experience architecture. In other words, your vision for how to increase orchestration backstage to deliver the front stage experiences more predictably, which is communicated in your stories.

As discussed in Chapter 3, “Exploring Ecosystems,” the method of service blueprinting can help you at this stage. If you created blueprints in your discovery, then you have familiarized yourself with issues and opportunities related to your current operations. You and your colleagues can now use future-state service blueprints to prototype more granular details of your envisioned customer pathways and what operations will need to do to support them (see Figure 9.5).

FIGURE 9.5

A future-state service blueprint.

EXPERIENCE BLUEPRINTING FOR PRODUCTS

We have referred often to “product or service or experiences” to signal the broad application of the book’s concepts and tools, regardless of label. This holds true for service blueprints. In some organizations in which I have consulted, I referred to this method as “experience blueprinting” when the term service proved to be a distraction to some stakeholders. In the end, it’s more important that you prototype how multiple touchpoints, channels, and other operational capabilities are orchestrated to deliver end-to-end experiences. What you call it (and how you connect it with other frameworks) is up to you.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

As there is a growing body of literature around the practice of service blueprinting, what follows is not an exhaustive how-to process. If you have never done a service blueprint, we recommend you dig deeper into the method.7 Once you have the basics down, consider the following guidelines to design your blueprints in coordination with the rest of your tangible vision.

• Get the right people in the room. A blueprint gives a bird’s-eye view of how different functions—technology, process design, training, product, marketing, and so on—may be called upon to contribute their expertise, time, and energy. Get these stakeholders in a room with some sticky notes and get to work. You can add things, remove things, or move things around as you explore how to deliver the intended experience. Together, you will see the chain reaction of different operational choices, allowing you to have focused conversations on what will work best.

• Work outside-in. Solution development often begins with what is operationally efficient or technologically supportable. Blueprinting flips this approach on its head. Your blueprints should derive from working through how a customer would successfully navigate an end-to-end experience, detailing the touchpoints and channels that they interact with along the way. Your individual ideas and storyboards should inform the scenarios and potential experiences that you blueprint (see Figure 9.6).

Once you have the front-stage details drafted, challenge your colleagues to find operational solutions to enable that experience. Frame this activity as its own “How might we?” For example, “How might we define operations to deliver the intended customer experience?” This is similar to the concept of challenges in strategic intent. In this case, the desired customer actions and outcomes set the intent, while employees are asked to use their ingenuity to find operational solutions to deliver upon it.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 9.6

Beginning the service blueprinting process on a whiteboard with sticky notes.

• Focus on key customer pathways. Choose scenarios to blueprint that reinforce key recommendations in your strategy and help tell the overarching story of what the future will be like for your customers and organization. Typically, so-called “happy paths” will appropriately flesh out your vision, but use your judgment. If you’re currently having issues with service recovery, then your blueprint may show how some customer journeys may get off track and also detail how your customers will get back on track in the future.

• Reinforce your journey framework. Your tangible vision needs to establish a common framework for designing and evolving your end-to-end experiences. Make sure that your blueprints call out the stages and moments that you identified in your research and are refined in your ideation. Refer to Figure 9.5 for an example of this approach.

• Don’t feel tied to the basic blueprint framework. If you do some research, you will find multiple service blueprint frameworks. Sometimes service evidence is the top row, each channel has a row, or touchpoints are placed between the customer actions and front-stage staff (our preferred standard approach). You should experiment with what works best in your organization.

• Highlight the big rocks. Any vision will have recommendations that are more critical or more challenging to execute. Consider highlighting these big rocks in your blueprint. For example, place a star icon on key touchpoints or put thick outlines on high effort process changes. Keep it simple, and these details can help others read and understand your blueprint better.

• Tie to operational roadmaps. As you prototype different operational solutions, you likely will explore leveraging existing, in-progress, or completely new processes, roles, and technologies. Perhaps there is a new customer relationship management (CRM) solution being planned for 18 months out, or store ops is splitting a general retail role into two new roles. It may be useful to call out these planned but moving targets to indicate that you have connected those dots or to reinforce the criticality of these planned changes to your vision.

• Show multichannel options. Your blueprint may include touchpoints that customers can experience in their channel of choice, such as receiving a confirmation by text, push notification, or a phone call. Make sure that you indicate this option on relevant touchpoints, as well as define what technologies and processes make this choice possible.

• Call out key metrics. As part of your vision work, you will need to indicate how value is created and where you can insert indicators to measure performance. Consider including key metrics in your blueprint to show important places to measure the impact of experience and operations.

• Combine with or connect to other artifacts. Finally, the classic boxes and arrows blueprint does not have to stand on its own. Simply combining your stories and blueprints creates a powerful combination of showing experience and supporting operations. Also, consider cross-referencing your blueprints with other artifacts, such as a future-state touchpoint inventory or evolution map.

Capability Descriptions

In Chapter 2, “Pinning Down Touchpoints,” we defined features as a subset of touchpoints that deliver a unique value or experience. This is closer to the marketing use of the term (although we recommend using human-centered approaches to identify and design features). However, end-to-end experiences contain many more moving parts than features. We call this super set of solution parts capabilities.

A capability is the thing that your organization must be capable of doing in order to enable a particular moment within a given stage of your journey. You can reframe most things you consider features as capabilities—such as thinking of the ability for customers to upload a profile photo. The reason for doing this is to keep those “features” on the same playing field as things that aren’t typically thought of as features. For example, “What are the most important capabilities for our call center during pre-onboarding?” In this case, the ability to create a seamless transfer from one representative to another might not be thought of as a feature, but could be considered a capability. Also, among the moments you support, uploading a profile photo and supporting seamless call transfers could be thought about in the same way. If you work in a purely digital environment, you may not need to reframe features as capabilities, but in a cross-channel, cross-functional environment, capabilities unify the different things you need to do. A capability encapsulates an operational component that supports the experience, such as the touchpoints, channels, processes, or roles.

Many of these capabilities will have come up in different activities and discussions that have led to your vision. You now need to define them more formally. Documenting your capabilities should be a collaborative effort. When defining each capability, consider the following:

• Describe the capability in enough detail that it can be understood by anyone across the organization.

• Identify the channels needed to support that capability.

• Map the capability back to a specific stage of the experience.

• Surface any major dependencies to enable the capability.

• Identify accountability for that capability.

When you bring people together to do this, the core team likely will take a stab at drafting the capabilities. The group can work together to ensure that each capability is articulated clearly, with little abstraction, and can prioritize the set of capabilities, typically along the lines of business benefits, customer benefits, and feasibility. Figure 9.7 illustrates how to use small cards to facilitate the definition and prioritization process. In prioritization, you may not get to every capability. Focus on the ones that are most important, documenting more details for capabilities that may be needed in the near-term. Further prioritization and sequencing of capabilities will then occur in evolution mapping (see “Determining Your Evolutionary Path”).

FIGURE 9.7

Capability cards.

As you identify and prioritize capabilities, you should map them to your Stories for the Future and blueprints to indicate the moments to which they align. This enables you to identify and discuss dependencies better. This is where having the cross-functional group together will be key. Lastly, with everyone in the room, you can determine who is accountable for each capability.

Future-State Touchpoint Inventory

It is also helpful to explicitly define the collection of touchpoints that must be created to support or trigger customer actions. Some of these touchpoints will appear in your stories and blueprints, while others from your ideation and prioritization may not. Don’t lose this good thinking!

Chapter 2 introduced the touchpoint inventory framework and the discovery approach of itemizing and organizing key touchpoints by channel and journey stage. This same framework can be used to document your future-state touchpoints. When crafting your vision, you probably have not identified all the touchpoints that customers will need. However, create an initial inventory with your known touchpoints. This will help colleagues begin to take responsibility for defining, designing, and maintaining the touchpoints for which they are responsible. Here are a couple of approaches to document an initial future-state touchpoint inventory based on your ideation and vision work.

• Simple: This approach leverages the framework used in your current-state touchpoint inventory, but is updated with your latest definition of journey stages. Your channel rows should also reflect what channels you will leverage in the future. In this approach, it is also useful to distinguish new touchpoints from existing touchpoints.

• Detailed: You can get much more detailed in your future-state inventory. You can break out your stages into discrete moments to document when touchpoints play a role in more granularity. Your detailed inventory can also highlight the expected impact to existing touchpoints, such as reimagined, modified, or as is. Figure 9.8 shows one approach to this type of documentation. In even more detailed inventories, connections between touchpoints and design direction are included. Your simple stage-channel framework (at a glance) should refer to these detailed spreadsheets (specifications and intent).

FIGURE 9.8

Part of an example-detailed touchpoint inventory. It maps each touchpoint (same intent, different design per channel) to channels and moments within journey stages.

Charting Your Course

In larger organizations, optimizing an end-to-end experience involves working with multiple groups, dealing with legacy systems, and navigating a complex political landscape of competing priorities. You should recommend a strategy of starting small, learning, and adapting, but also provide guidance for how work across multiple fronts will eventually coalesce into a holistic experience.

This is a balancing act. For example, say that you have crafted a vision for a better end-to-end experience for ordering online and picking up in store. This new customer journey will require changing or creating touchpoints in multiple channels. Operations will need to design processes, marketing will create new collateral, and the learning department will develop employee training. Your stories, blueprints, and other artifacts will give these efforts a tangible vision of what to aim for in execution. Yet, you must enable flexibility to address yet unknown constraints, implement and refine iteratively, and inform other work efforts.

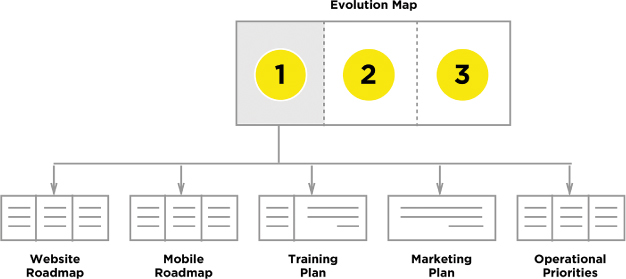

Given these dynamics, you must define how to take intentional steps toward your vision while leaving room to learn and adapt along the way. This guidance is delivered in the form of an evolution map. As you will see below, an evolution map shares many best practices with a good product roadmap but takes a broader view than a product and its features. It informs disparate products, technology, and operational roadmaps to align them in support of the North Star (Figure 9.9). Most importantly, an evolution map has an experiential bias to ensure that customer needs stay front and center over time.

FIGURE 9.9

An evolution map provides context for other roadmaps and plans.

Determining Your Evolutionary Path

While creating your vision, you and your collaborators will swim in ideas, potential solutions, opposing priorities, possible stories, and feasibility questions for some time (see Figure 9.10). At some point, your strategy will become clear. A pathway will present itself that embraces known constraints, delivers value to stakeholders, and feels achievable by your organization. Your evolution map documents this recommended course of action.

FIGURE 9.10

Through multiple iterations, you can settle upon your vision and the pathway to improve the end-to-end experience over time.

If you have experience with developing roadmaps, then you know there is a natural tension between acting now and building support for larger investments of time and money. Defining near-term action (in part driven by quarterly and annual cycles in corporations) often displaces architecting and committing to solutions that require more time to bear fruit. Orchestrating experiences, however, requires breaking down this organizational muscle memory. Your vision orients others to the horizon; your evolution map frames actionable steps to move together in the desired direction (see Figure 9.11).

FIGURE 9.11

Through multiple iterations, you can settle upon your vision and the pathway to improve the end-to-end experience over time.

Your mantra must be “work backward from our vision.” In practice, this means taking your envisioned end state—as communicated in your stories and blueprints—and determining how to move in that direction over time. This mindset derives from the work of the University of Waterloo’s John B. Robinson. In his research at the intersection of environmental change and public policy, Robinson outlined an approach—called backcasting—for defining a desired future and then determining the most viable actions to take to attain it. His method moved the emphasis from predicting possible futures to analyzing the effort and investment required to live into a future that you would like to see.8 Matthew Milan, CEO of software innovation firm Normative, helped to widen its application to information architecture and user experience.9

In the context of product and service experiences, your nascent vision provides examples of end-state outcomes from which to backcast. Backcasting for orchestrating experiences has one differentiation: where traditional backcasting often identifies multiple future state hypotheses, here you typically have a singular vision of the future toward which you want your capabilities to evolve.

BACKCASTING FOR ORCHESTRATING EXPERIENCES

Backcasting often involves identifying multiple possible futures and then mapping the opportunities and barriers that exist on the path to those futures. When you’re orchestrating experiences, you typically have a singular vision (or set of vision stories) that define the future experience you want to support and the capabilities needed to support them. Backcasting used here is specifically designed to orchestrate the evolution from the baseline current state to a more singularly desired future state.

You could also use backcasting earlier in the process when you’re defining that future state and look to see which path is better—more achievable, more competitive, etc.—among multiple future state possibilities.

It’s important to reinforce here that this is an iterative process. As you define your stories of the future, your blueprints, and your capabilities, you are still circling around a vision that your organization will commit to. As you begin to map a potential evolutionary path, you will naturally sharpen your vision as the feasibility and impact of different options become clearer. In each iteration, however, the key is to let the desired future drive your analysis so that your intent isn’t lost along the way.

Evolution planning can easily wrap you and others around its axle with so many variables at play—competitive pressures, feasibility, effort, timing, dependencies, and so on. To avoid this, lean heavily on the journey framework that has emerged through your sensemaking and vision activities. While your stories from the future will take several iterations to achieve, journey stages and moments (and customer needs within them) provide a consistent structure to plan and coordinate improvements to the end-to-end experience over time.

Take air travel as a case. As a service experience, technology advancements and increased security requirements have transformed how passengers plan a trip and get to their destination. These changes, however, sit upon a more consistent architecture of moments—choosing a destination, booking your flight, going to the airport, checking in, and so on. If you were tasked with an air travel initiative today, you would look to transform these moments to improve them, rethink their sequence, or replace them.

Your journey framework can serve as a table of contents for your product or service experience evolution. Working backward from your stories of the future, you should weigh different options for when and how to address each journey stage and moment. This means asking questions such as:

• Which journey stage(s) and moment(s) will you address first? Next?

• For each moment, will it remain the same over time, change once, or evolve in a series of steps?

• When will you introduce new moments, or remove an existing one?

• When will your key features be introduced? Will they be executed in phases?

• How will your channel strategy evolve? Can you leverage some channels for interim solutions?

• What big rocks—new platforms, channels, roles, and so on—must be tackled (and when) to enable moments and touchpoints?

• How will you work with major dependencies? Do you need interim solutions to deliver value while waiting for your capabilities to line up?

As you explore how your stages and moments will evolve, you will naturally begin analyzing how the roles of various channels, key touchpoints, and capabilities will also change independently or in concert. Some of your decisions may be driven by implementation constraints, while others may fall later in your plan due to dependencies, urgency, or value.

For example, your long-term vision may be to partner with Lyft to schedule a pick-up service to the airport when booking a flight. The optimal solution would involve changes to several channels, backend integration, training, and other efforts. While this is not feasible to tackle fully in the near-term, your challenge is to identify manageable steps that you can take to move toward your vision for this “schedule a ride to the airport” moment (see Figure 9.12). The plan for this moment, of course, impacts the evolution of later moments, such as “leaving for the airport” and “arriving at the airport.”

FIGURE 9.12

Backcasting booking a ride to the airport.

Throughout your evolution mapping activities, use your experience principles to pressure-test your options for initial or interim solutions. For example, your vision for a hotel service experience may include personalizing room amenities based on a guest’s profile. This solution is not achievable now due to technical reasons. Yet, one of your experience principles is “to fit like a glove.” Reviewing your near-term evolutionary stage against this principle helps to reveal this gap. You and colleagues can then challenge yourselves: “How might we make the guest’s room fit like a glove within our near-term technical constraints?”

Mapping out how to evolve moments, as well as the entire journey, is hard work, but keep focused on your intent and framework to navigate the unavoidable ambiguity. Eventually, a sequence of actions will emerge, as well as how to organize them into phases. You are then ready to document your evolution map.

Communicating Your Evolutionary Pathway

You have many options for designing your evolution map. As with other artifacts, you should choose an approach appropriate for your culture while crafting it to stand out from the pack. Common forms include a large canvas, a series of slides, a book, or a combination of all three. Get creative!

Regardless, make sure that your evolution map works in concert with your stories from the future, blueprints, capabilities, and other documentation. Cross-reference as much as you can so that people can easily dig into the details without getting confused on the big picture. Your vision and evolution map package should tell a story that inspires others to follow your recommended course of action and stay in alignment with your tangible vision.

While the form of your map is up to you, consider the following guidelines to ensure that you communicate the important details of each phase on the pathway ahead of you clearly.

• Organize by phases with themes. As in a roadmap, you should organize your evolution map into distinct phases with clear entrance and exit criteria. Each phase should have a theme that communicates its intent. For example, you may come to the realization that your first evolution will focus on updating your content strategy because it will not require new investments in operational infrastructure. The theme of this first stage, therefore, might be defined as “improving customer communication.” You may also determine that you can do better data collection to enable new interactions and value. So, your second stage might be called “getting smarter.”

• Don’t align to dates. Avoid giving each phase a specific time frame, such as first quarter. An evolution map should show a sequence of phases and the relative length of phases. You should not tie your phases to dates. Leave that to more detailed program planning to nail down details of timing and funding.

• Communicate value and measurement. Within each phase, break down how your efforts will result in better experiences that deliver measurable value to various stakeholders. This is especially critical in the early phases in which business and technical outcomes often push out to later (or never) the value that is to be created through customer experience. By being explicit about value in each stage, you will reinforce that customer (and other stakeholder) value is a key part of your success criteria.

• Align to stages and moments. As covered previously, your evolution map should call out when you will address each journey stage and moment. Communicate clearly the focus of each phase, as well the individual evolutionary path of specific moments (see Figure 9.13).

• Call out features, channels, touchpoints, and operations. You should show how the role of channels will change in each phase, as well as what the plan is for key features and touchpoints. Each phase should also note operational changes—technologies, processes, and people—required to support the intended experience. Refer people to your capability descriptions and future-state touchpoint inventory for the nitty-gritty details.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 9.13

Example of an evolution map.

• Define ownership, accountability, and dependencies. Many functions and groups will be needed to put your plan into action. Make sure that you annotate your map with who will be involved in each step, what you will ask of them, and what any major dependencies will be.

• Know what you want to learn. Finally, the spirit of a tangible vision and evolution plan is to adapt to changing circumstances while not losing sight of your original intent. Be explicit as to what you want to learn in each phase to validate your original course of action. This will help ensure that your evolution map evolves with new evidence.