CHAPTER 8

Generating and Evaluating Ideas

CHAPTER 8 WORKSHOP: From Ideas to Narratives

With your opportunities informed and framed as questions, you can now unleash your colleagues to address them with confidence. But how do you come up with promising ideas? And how do you wade through all those ideas to land upon viable solutions?

First, you must embrace the fact that people across your organization not only have a stake in future solutions, but they have ideas, too. Your colleagues have important viewpoints and knowledge, pre-existing solutions already in roadmaps, and the very human need to contribute to defining the future (not simply executing someone else’s vision). Therefore, you need to build on the collaborative atmosphere that has been established while engaging others to generate and explore new ideas.

Generating ideas with many people of different skills, knowledge, and experience is critical at this stage, but it does come with some challenges. Many of your colleagues likely have lived through poorly facilitated brainstorming sessions that resulted in groupthink or dominant voices shouting out other perspectives. New collaborators may challenge prior research and the opportunities you have identified because they did not have a direct hand in it. And that’s if you can get everyone to free up the time to participate. Your job, therefore, is to design working sessions and other activities that mitigate these challenges and produce quality ideas to further evaluate and choose. This chapter will equip you to do just that.

Leading the Hunt for Ideas

A plethora of books and resources exist on the topic of generating ideas. Advocates and detractors argue over the efficacy of brainstorming alone or in groups. Hundreds of proprietary approaches tout their methods as the most predictable ways to achieve innovative results. And then there’s the old truism: “I get my best ideas in the shower.”

Let’s face it—ideas are mysterious. They can come at any moment during any phase of your initiative, project, or sprint. And most of these ideas—despite the refrain “there are no bad ideas”—end up being off topic, unviable, or simply never acted upon.

That said, you can successfully engage others in generating ideas and working toward agreed-upon solutions based on your identified opportunities. This process won’t happen in a single workshop. It requires careful planning, a variety of inputs and methods, and strong facilitation. It also takes a little creativity and a lot of flexibility. Let’s look at four aspects of designing and managing collaborative sessions:

• Structure and focus

• Inputs and constraints

• Expression and form

• Evaluation and prioritization

Structure and Focus

As with any orchestration endeavor, structure and focus in your ideation activities are critical for a positive outcome. How you plan to engage your colleagues (and customers) depends in part on your context. If you have stakeholders across a broad geography, you may want to hold workshops in multiple locations or mix in remote sessions or individual ideation. A hierarchical culture may require you to increase the size of your sessions to include multiple layers of decision makers and influencers. A tight schedule could force you to hold open sessions based on availability instead of having ideal groups for specific sessions.

Regardless of your context, you should consider the following guidelines to set yourself up for success:

• Communicate ahead. As you engage a cross-functional team in discovery and research activities, you should communicate early and often how new ideas and solutions will be addressed later in the process. People are natural problem solvers, so this will help manage their expectations while nudging them not to jump to solutions too quickly.

• Put emerging ideas in a parking lot. When ideas inevitably bubble up, don’t lose them! Gather emerging ideas in one place and save them until you are ready to move from sensemaking to solution definition. You can bring these into your workshops to be revisited, built upon, and evaluated along with new ideas that your sessions generate.

• Hold multiple sessions. End-to-end experiences have many moving parts and even more stakeholders. For both practical and quality reasons, don’t attempt to tackle all your idea generation in one large (and very long) workshop. Instead, hold several sessions to explore different opportunities, engage specific stakeholders (who may be in different geographic locations), try different methods, or to simply marinate on the outputs of previous sessions as fodder for more ideation.1

• Don’t “blue sky” brainstorm—focus! Collaborative ideation works far better with a clear focus, not through free-for-all spitballing. Leverage your opportunities to provide this focus. You might consider organizing sessions around specific opportunities by theme—such as by customer type, opportunity area, or journey stage—inviting participants with the most stake or subject-matter expertise (see Table 8.1).

TABLE 8.1 IDEATION BY TOPIC

Session |

Opportunities |

Participants |

1—Product research and wayfinding |

How might we help customers find products more easily while in the aisles? How might we help customers continue their product research when they leave the store? |

Core team Store operations Floor associates Product Mobile Customer insights Enterprise information architecture Store environment team |

2—Returning purchases |

How might we make the returns waiting process less frustrating? How might we connect online and offline returns better? |

Core team Store operations Returns associates Mobile Returns product manager Legal Process engineers |

3—Entry experience |

How might we provide a better sense of welcome when entering? How might we support customers on a time-sensitive mission in the entry experience? |

Core team Marketing Target customers Store operations Floor associates Digital |

• Strategically engage your stakeholders. Participants for each ideation workshop should be carefully selected to ensure that the proper functions are represented. People’s time is valuable, and sessions need to be relevant to their responsibilities, expertise, or role. Make sure that no one leaves a session questioning whether to accept a future invitation.

• Stay organized and keep everything. Your sessions will generate hundreds of ideas. While most will end up on the scrap heap, don’t abandon ideas that don’t float to the top. Take pictures or scan all your outputs and keep them organized and accessible.

• Have clear evaluation criteria. Begin with the end in mind. Define how you will evaluate and prioritize at the beginning of your hunt for ideas. You should communicate this at any sessions as part of general context setting.

NO IDEAS LEFT BEHIND

In previous chapters, I shared my fondness for kicking off new initiatives with a workshop to capture stakeholders’ current thinking on the problem space. These sessions are also a good time to gather many of the pre-existing ideas that people have for solutions. Often, I’m guiding people who have spent months or years saving ideas and waiting for the time or money to do them justice. Gathering these early on helps bring these ideas out of the shadows. Most of them do not make it through the process (once the problem space is properly reframed), but it’s good to know if any stakeholders (or myself!) are anchored to pet ideas. It’s even better when a pre-existing idea gets honored once its appropriateness becomes clearer.

Inputs and Constraints

Opportunities give a specific focus for ideation in and across sessions, but they aren’t your only inputs. The many insights and frameworks that emerged during sensemaking now become tools to help your colleagues explore solutions creatively. Touchpoint inventories, experience maps, and ecosystem maps provide proper context to optimize or reimagine the end-to-end experience. Personas and other models ensure that the needs of people remain top of mind and inspire better ways to serve various stakeholders.

Most critically, experience principles should be used throughout the ideation process. They can be combined with other inputs—opportunities, journey stages, unmet needs, channels, or technologies—to prompt a range of creative solutions. Throughout this chapter, several examples of using principles to generate and evaluate ideas are provided.

In addition to sparking new ideas, these inputs serve as important constraints to keep ideation focused and productive. This is a delicate balance. Well-framed opportunities—“How might we . . . ”—provide a springboard to go beyond overly constrained problem statements, and human-centered frameworks encourage you and your colleagues to set aside personal viewpoints and biases. However, all these inputs and variables can be overwhelming. Table 8.2 shows examples of combining different inputs to constrain and focus idea generation. For any opportunity, however, you should mix your inputs in different ways to see what leads to the best results.

TABLE 8.2 FOCUSING IDEA GENERATION

Prompt |

Input/Constraints |

How might we help customers find products more easily while in the aisles? |

Customer journey type (mission or research) + experience principles |

How might we help customers continue their product research when they leave the store? |

Journey stages (before, during, after) + experience principles |

How might we make the returns waiting process less frustrating? |

Journey stages + analogous inspiration |

How might we provide a better sense of welcome when entering? |

Personas + channel |

How might we support customers on a time-sensitive mission in the entry experience? |

Journey stages + technology |

One question that always comes up that you’ll want to plan for: “What about feasibility?” Your objective at this stage is to produce a large quantity of possible new solutions, so you should not constrain yourself to what your organization can or probably does now. However, you do want to stay within some boundaries, if only to honor the laws of physics or the natural abilities of people! Here are some tips on managing the question of feasibility:

• Be clear on your timeline and intent. Are you looking to optimize a set of touchpoints in the next three months or instead look years into the future to reimagine the end-to-end experience? This context will help people feel out their boundaries, but encourage them not to let perceived feasibility overly constrain their ideas.

• Focus on experience. Prompt colleagues to come up with ideas for the best possible experience, not the most likely experience (given how they interpret feasibility).

• Work backward from ideal. Once you have ideas to work with, you can begin to evaluate them iteratively against feasibility (and other criteria). Your eventual solutions may not be the ideal represented in the original ideas, but they can retain the original kernel that addressed the opportunity. Your solution may also have its own evolution plan to become closer to the ideal over time (see Chapter 9, “Crafting a Tangible Vision”).

• Build new prompts. Ideas that push beyond perceived feasibility boundaries can be turned into new prompts or challenges. For example, an idea to provide product research recommendations using a mobile app could be explored using the prompt: “How might we provide personal product recommendations without the use of new technology?”

Expression and Form

In addition to playing with different inputs, you can employ a variety of methods to generate ideas. The following three methods (see Figure 8.1) are highly effective in the context of collaborative sessions for idea generation for end-to-end experiences: visual brainstorming, crafting stories, and bodystorming.

FIGURE 8.1

Three effective ways to generate and explore ideas for your opportunities.

Visual Brainstorming

You have likely participated in brainstorming sessions in which participants write down ideas on sticky notes that are then organized by affinity and labeled. As noted earlier, this kind of ideation has as many detractors as advocates, with research to back up both perspectives. That said, brainstorming, when done correctly, is a good method to generate the seeds for some real solutions, as well as a constructive way to engage various stakeholders with different skills and viewpoints.

Consider the following when using brainstorming for end-to-end experiences:

• Play with different inputs in timeboxed rounds. As noted earlier, structure and focus are critical to any idea generation sessions. Brainstorming works best in short, intense bursts of activity followed by time to evaluate and reflect. A good approach is to divide your session into rounds, each with a different opportunity or combination of variables. Rounds could focus on each stage of the journey, a different persona, or a subset of experience principles. Each round should have a set time limit (typically, 4–6 minutes). For example, ”How might we help customers continue their product research when they leave the store?” could be approached in a couple of different ways to prompt new ideas (see Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2

Two different approaches to designing rounds in a visual ideation session.

• Go for quantity. Each round of ideation should result in multiple ideas per participant. As in other brainstorming approaches, go for quantity over quality and feasibility. Encourage participants to spend less time adding details to ideas and more time getting the next one out of their heads.

• Show the experience. While brainstorming often involves writing ideas down on sticky notes, words can be ambiguous. Expressing ideas visually communicates the nuances of an idea more clearly. Have participants name, describe, and draw each idea to make sure that the full concept is captured. As shown in Figure 8.3, a quarter sheet (of A4 or 8.5" x 11" letter) provides enough space to express ideas visually while not encouraging unnecessary details.

FIGURE 8.3

Show, don’t tell.

• Start individually and then share. Avoid “popcorn” style brainstorming in which participants throw in ideas at the same time. This approach leads to dominant voices taking over the session or groupthink. Instead, let each person generate ideas alone each round, and then have participants take turns sharing their ideas.

Crafting Stories

The one-idea-per-paper approach in visual brainstorming has the advantage of generating many ideas quickly, but it limits concepts to a single expression or a singular moment. The opportunities to improve or invent new end-to-end experiences should also be explored in formats that support thinking through experiential flow better. This means generating ideas for new sequences of customer interactions from need to need, touchpoint to touchpoint, or channel to channel. Stories provide the best form for this type of ideation.

Stories push you and your colleagues to generate and express your ideas from a human perspective. Typically, the customer is the story’s protagonist as you show how improved or new touchpoints help that person meet and accomplish explicit goals or meet implicit needs over time. You can show not only what customers may do in the future, but also how they may think or feel as they interact with a new solution in a realistic context. Other people in the customer’s ecosystem—including your organization’s front-line employees—play roles in the narrative. The story’s setting is the customer’s world, not the world of your organization.

Stories do have their limitations. They take longer to produce, so you get less quantity than other methods. Less commonly used than sticky note brainstorming, they require more instruction and facilitation to get cross-functional groups comfortable and productive with the method. These limitations aside, storytelling is a natural human inclination. You and your colleagues will have collected and analyzed many current-state stories from your customers and other stakeholders. Once comfortable with the method, workshop participants typically find that narratives provide a familiar form to express their ideas. Stories are more engaging when presented. In addition, they build customer empathy and are remembered more easily. In the end, they will help everyone come up with ideas for not just what parts of a product or service could do, but how they may be experienced.

When using stories to generate ideas, you should vary the inputs as you do with other methods, as well as focus participants on your identified opportunities. Also, consider the following when crafting stories:

• Get visual. As with visual brainstorming, you want to show, not tell, to reflect the richness of the customer’s context and your ideas. Encourage participants to use a third-person omniscient point-of-view and change the perspective to focus on the most important action (see Figure 8.4).

FIGURE 8.4

Show the experience from different experiences to focus on the most important details of your ideas.

• Show more than actions. A visual format also makes it easier to show what customers think and feel and how new solutions could create new thoughts and feelings. Prompt participants to use facial expressions and body language for emotions. Thought bubbles can be used to reveal internal dialogue.

• Pair visuals with descriptions. Illustrations can do a lot of the storytelling work, but descriptions should be used to flesh out the narrative. They can call out the specific opportunities addressed, customer and business benefits, and specific features or capabilities that enable the proposed experience.

• Go backstage. For services involving other actors, it may be necessary to illustrate activities unseen to the customer to express the full idea. Panel three in Figure 8.4 shows one approach to showing backstage moments.

• Use a storyboard template. To help participants feel more comfortable with storytelling, design templates for your sessions. These can be a single sheet with multiple panels (typically, three to five) or single sheets that can be connected to form multiple scenes. Include sections for naming the story as well as space to illustrate and describe each panel. You can also include additional space to capture other elements, such as needs, journey stages or moments, or experience principles (see Figure 8.5).

FIGURE 8.5

An example of a storyboard template for idea generation.

• Pull out the ideas. Once you have a bunch of stories generated, you can mine them for individual ideas within them. You will typically see some of the same ideas of what to do with different ways of how to do it, ideas in one channel or medium that could be moved or extended to other channels, or ideas in different stories that can be combined and built upon.

• Pair with visual brainstorming. Another way to use stories: pair them with visual brainstorming to connect and help ideas evolve. The workshop following this chapter illustrates one way to combine these methods.

USING TEMPLATES

When using stories to connect individual ideas, I recommend creating templated concept cards in quarter sheets or half sheets of A4 or letter. Each card should have room to identify the stage of the journey that the idea addresses, the specific opportunity (or “how might we”) being addressed, and other details, such as what channel, media, or other resources (such as staff) are involved. This isn’t so important when doing the visual brainstorming, but when the ideation activity can produce dozens of ideas, having your cards coded like this makes a huge difference when sorting through them later. For example, you can easily cluster ideas by stage or opportunity, or have discussions about the channels or media involved.

Bodystorming

A third effective approach is to put aside paper and pen and use your voice and body. Sometimes called bodystorming or service storming, this approach involves acting and improvisation in small teams to generate, connect, and build upon ideas (see Figure 8.6). The point-of-view shifts from third-person omniscient to first person, as participants experience directly what various customer touchpoints may be like to interact with, the flow through different moments, and the emotions interactions invoke.

COURTESY OF RICHLAND LIBRARY

FIGURE 8.6

Generating new ideas through acting.

While some participants may be resistant at first to bodystorming, the benefits are numerous. In addition to simulating what a customer may experience, acting and improvisation engage different parts of the brain than other idea-generation methods, boosting creativity.2 Getting up and playing creates a different energy, helping you and colleagues to break out of typical modes of work interaction. Improvisation also has a unique form in which one simultaneously presents a problem, generates ideas, and tests the efficacy of those ideas.3 Without any tools but your bodies, this approach is also flexible and fast, supporting multiple iterations of generating and evolving ideas in a short amount of time.

Consider the following when bringing improvisation and acting into your idea-generation sessions:4

• Warm up. Get your participants warmed up using a series of improvisational exercises. (Good ones are easily found online.) In addition to loosening people up and checking for participants’ comfort levels, these exercises will reinforce the core improvisational concepts of not overthinking what to do (Just do it!) and building on ideas (Yes, and!).

• Work in small teams. Using your opportunities and other inputs to organize around, divide into small teams to generate ideas together. Participants should build upon each other’s ideas, simulating an experience by embodying different actors and touchpoints.

• Play with ideas before building a narrative. Give teams time to play around with different ideas before moving too quickly to a cohesive story. Encourage them to keep looking at the opportunity using different variables (principles, channels, personas, and so on) before locking onto a specific experience to evolve.

• Adapt to a narrative structure. After exploring ideas, help teams shift into constructing narratives by giving them a simple structure. This could be three chronological scenes (as with the storyboarding technique), a problem-resolution story, or contrasting current-state and alternate future solutions.

• Capture what happens. The ephemerality of acting out experiences means that you have to capture the outputs in another medium. Common approaches are to video the session, take pictures and later build into an annotated storyboard, or have other participants write down what ideas stand out to them.

• Combine with other methods. Improvisation and acting can also help connect and evolve ideas generated by other methods. You can take individual ideas from visual brainstorming into improvisation, create storyboards based on your improved ideas, or act out your storyboards and then watch them evolve.

Evaluation and Prioritization

At some point, you will need to rein in your ideation process and start selecting the most promising concepts with which to move forward. You may have a sense for some of the best ideas already. Perhaps they bubbled to the top in individual sessions. Or you may have seen common themes emerge across sessions that indicate where to focus.

Transitioning from what you might do to what you should do can be tricky. For end-to-end experiences, your proposed solutions will impact many parts of the organization. For example, going forward with an idea requiring marketing, product, technology, and operations to coordinate their activities will generate many questions about feasibility and trade-offs in each function. This is why cross-functional collaboration is so critical before, during, and after generating new ideas. The more that key stakeholders understand and buy into where you are collectively heading, the easier it will be to get down to brass tacks.

Making sense of the many proposed ideas and concepts, therefore, follows the patterns recommended throughout this book. These include:

• Involve a broad range of colleagues.

• Leverage simple frameworks and principles to aid decision-making.

• Be clear on your focus, whether it be optimization, reimagining, innovation, or some combination of the three.

• Keep everyone centered upon ideas that deliver value to people, not just the business.

• Look for connections that bridge moments, touchpoints, and channels.

Going Beyond Workshops

In addition, it is important to be rigorous in your evaluation and selection of ideas. This ensures that others can trace back your eventual solutions to the concepts, opportunities, and insights that gave birth to them. Here are a few tips for keeping organized and working with others to land upon the best ideas to act upon.

Play, Prototype, and Connect

While each idea should be evaluated on its own, it’s important not to lose sight of how they may connect in various ways to create greater value. You should iterate looking at the parts (ideas) and the whole (multiple ideas that collectively create better end-to-end experiences). These iterations begin in your workshop sessions and should continue as you circle around the most promising ideas. See the workshop following this chapter for an example of this approach.

You should also build in iterations with your customers and employees to validate that your concepts are on the right track. This could be as simple as creating storyboards of key scenarios and paper prototypes of key features and touchpoints. Or you could hold codesign sessions with customers, front-line employees, and other stakeholders to role-play or construct new concepts to meet their needs.

Service blueprinting is also a good tool to use at this stage of the process. You can use blueprints to work with others to explore the feasibility of concepts you have documented in storyboards or through acting. See the next chapter for an overview of this approach.

Codify Your Ideas

To make it easier to compare and connect ideas, you should design a classification approach. You should put this in place as early as possible, because it may impact how you design your templates or store the outputs from your workshops and other approaches. For example, you might add a space for “stage” on your visual brainstorming templates to be able to see or document all the concepts by stage more efficiently.

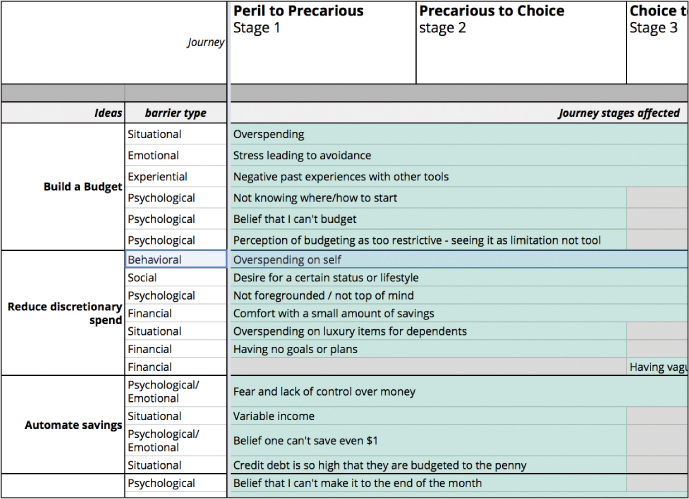

You likely will have a slightly different list of things you want to track or describe. That said, Table 8.3 lists common facets that should be helpful in being able to evaluate ideas from multiple useful angles. An example for each facet is also provided.

TABLE 8.3 EXAMPLE IDEA SCHEMA

Facet |

Description |

Example |

ID |

Unique identifier |

001 |

Name |

Unique name |

Augmented Reality aisle wayfinding |

What |

Textual and visual details for what the idea is and how it is experienced |

An augmented reality mobile camera data overlay that a customer can use to locate shopping list items by aisle |

Who |

Persona, customer role, or other stakeholders |

Authenticated customers with mobile account |

When |

Stage or moment |

Shopping the store |

Where |

Channel and/or physical location |

Aisles and departments in retail channel, mobile app, web |

How |

Operations, partnerships, key technologies |

Store operations, mobile app dev, digital team, merchandising, marketing |

Why |

Value to business, customers, employees, and other stakeholders |

Business: more items move from shopping list to purchase; Net Promoter Score (NPS) Customer: time saved finding items Employees (store): help with wayfinding requests |

Connects To |

ID numbers for what other ideas this is similar to or could be combined with |

007, 103, 105 |

Opportunity |

Opportunity or “How might we?” |

How might we help customers more easily locate the items that initiated their shopping trip? |

Depending on your context, the robustness of your organizational approach will vary. A smaller project or end-to-end experience may only require some detailed lists or large sticky notes on the wall. If you are dealing with dozens of ideas or a more complex product or service, spreadsheets are great for itemizing and describing all your ideas. They are especially useful for sorting and filtering ideas by facet. Figure 8.8 shows one example of this approach.

FIGURE 8.8

Idea spreadsheet.

USING SPREADSHEETS

I tend to go the spreadsheet route, even for smallish projects, because it allows me to evaluate ideas from different angles very quickly. Spreadsheets can also be used in combination with InDesign’s data merge feature to automate making tools and visualizations. For example, it’s helpful for making cards with each idea on them to use in a prioritization exercise.

Rate for Value and Feasibility

After you have identified the most promising ideas, your next task is to rate each one based on its value and feasibility. This part can be tricky, because most organizations have multiple ways of measuring value and impact. Lean on your cross-functional team again to find a rating system that will work for your needs. Before rating or prioritizing any ideas, you must find how you will collectively define criteria for what makes something relatively valuable or feasible.

Here are a few steps to consider that will help you do this effectively.

• Get the lay of the land. Bring stakeholders from relevant areas together to compare how they each measure value and determine the feasibility of different solutions. See if you can find key commonalities and contradictions.

• Define common value and feasibility scales. Work with your team to explore a common set of criteria for value and feasibility. For example, you may identify separate metrics for business value (improved NPS, creating efficiency, generating revenue, and reducing call center volume) and customer value (feels more confident, reduces effort, and increases enjoyment).

• Get the right stakeholders to rate each item. Once you have common scales, you will need to engage stakeholders who have the knowledge to compare the value and feasibility of your ideas. You may do this through a series of workshops or conversations. If you use the spreadsheet approach recommended previously, you can use it to document the evaluation.

Prioritize

At some point, you will need to end your process of evaluating ideas and make some decisions. Work with your colleagues to finalize your analysis of which ideas and future experiences will make the cut. The prioritization approaches covered in the previous chapter can be repurposed here, as well as the “Value vs. Complexity” approach in the sidebar that follows. Then it’s time to pull all your threads together, craft your vision, and present your plan to the organization (see Chapter 9).

Prioritization: Value vs. Complexity

REMOTE WORKSHOPS

Before moving on to the last workshop of the book, I'd like to put in a good word for remote workshops. While it’s more effective to get people in a room together to collaborate, your timeline or budget may not accommodate this idea. Here are a few tips when you need to go remote:

• Keep it hands on. While remote collaboration tools (in which you type and move objects around digitally) have some benefits, they lack the tactile interactions that come with analog tools. A better approach is to use video to see one another and show your work, while still having people work through exercises with paper tools.

• Give yourself more time for activities. Everything takes longer to do in remote sessions due to lagged communications and synthesis steps that require more time in this format. You may have to split what would be one in-person workshop into a couple of shorter sessions to keep peak focus, energy, and attention.

• Design templates. Without you in the room, people need more instruction and structure to work effectively. For this reason, avoid blank sticky notes as much as possible. Design simple templates with instructions that help people understand the form their ideas should be documented in.

• Leverage mobile phones or scanners. Many ideation methods follow a generation and then evaluation cadence. In remote sessions, have participants work individually and then send in photos or scanned documents of their work. Give them a break, and then magically print and cut their work and place it on a large board. You can then walk through the items on camera, moving and organizing them as people give input and see the results.

• Train cofacilitators. If possible, assign and prep cofacilitators at each stakeholder location.

CHAPTER 8 WORKSHOP FROM IDEAS TO NARRATIVES