CHAPTER 11

Taking Up the Baton

Increasingly, business leaders understand the critical nature of customer experience to their bottom line. Walk the hallways of your organization, and you will likely hear phrases such as customer-centric, Voice of the Customer, and Net Promoter Score. You will see proclamations that all experiences should be simple and seamless while wowing your customers. You may also notice increased investment in human-centered approaches, such as design thinking, as well as skill sets needed to plan, design, and implement customer touchpoints.

These developments indicate good intent (and great demand for designers!), but most organizations still struggle to understand customer needs effectively or translate that understanding into well-designed end-to-end experiences. Why? In our work, we have seen many barriers, including:

• Talented people of all disciplines still work in silos, unable to see or contribute to a compelling experience vision.

• Customer research is insourced and outsourced, keeping decision makers and practitioners at arm’s length from people’s real needs.

• Strategy and planning remain largely tied to specific channels, products, and functions, not customer outcomes.

• Execution has become more iterative, yet agile is largely driven by business and technical considerations, not the needs of people.

• Organizations are trying to become more collaborative, but employees lack a shared language and philosophy for the role of customer needs, experience, and design in achieving business objectives.

Our objective for this book was to share a mindset and methods for taking on these challenges. There is no silver bullet. It takes hard work, inspired leadership, grit, and a little luck to orchestrate experiences. Yet, we have seen individual teams and entire organizations make great progress through employing the approaches outlined in previous chapters. We hope you and your colleagues will be able to do the same. To that end, here is some final advice for gaining traction in your organization.

Embrace Your Context

There are many paths that you can follow to influence how your team or organization orchestrates experiences. These paths each begin at the same point—your unique context. You may work in a relatively small company with touchpoints that you can count on a few hands, or you might have thousands of fellow employees with multiple business units, products, and services. Your organization may be hierarchical or flat, collocated or spread across a large geography, and have a mature or nascent design group.

Regardless of your situation, you need to take stock of the current state of your product or service experiences, your would-be collaborators, pre-existing plans for the future, and how work gets done in different organizational pockets. Here are a few ways that you can get started.

Document Your “As-Is”

For reasons stated earlier, you and your colleagues probably lack an understanding of all the moving parts of the current end-to-end experience. This makes everyone’s work more difficult and less effective. For example, product and marketing teams may have the same goal of increasing customer knowledge, yet not realize that they have duplicated efforts due to a lack of visibility into each other’s work. Customers eventually feel this pain through too many options, conflicting information, or touchpoints that simply don’t connect.

This is where you can make an impact immediately. Part I, “A Common Foundation,” introduced approaches that help people see the big picture. Here’s a quick summary of where you might begin. Each approach will deliver immediate value with relatively low effort and expense. They will also help establish language, concepts, and frameworks to build upon later.

• Create a touchpoint inventory. Get a cross-functional team together and map your touchpoints by channel and journey stage (see Chapter 2, “Pinning Down Touchpoints”). Align around the purpose and efficacy of each touchpoint. Try to identify ways to collaborate more effectively across journey stages and channels.

• Gather existing principles. Track down principles (or guidelines) that different groups use to guide work. Partner with colleagues to establish a common set of principles, either by synthesizing existing ones or doing new research with customers (see Chapter 6, “Defining Experience Principles”).

• Catalog current personas and journeys. Locate all relevant personas and experience maps floating around. (You will likely be surprised at how many you find.) Work with others to rationalize these into a foundational set of customer archetypes and journeys to support cross-functional strategies and planning. At the same time, you will uncover gaps in knowledge that may lead to new customer journey research (see Chapter 5, “Mapping Experiences”).

• Make a current-state blueprint. Select a critical customer pathway (such as onboarding) and create a current-state blueprint. Make sure that you invite a cross-functional team. You might also consider annotating your blueprint with upcoming operational changes that may impact the experience in the future (see Chapter 3, “Exploring Ecosystems”).

• Look at the numbers. Get your hands on any scorecards, reports, or other data that can help you understand the range and quality of your touchpoints. Then you can augment your touchpoint inventory, experience map, and service blueprint.

TAKE A SERVICE SAFARI

Service safaris are a common method in service design, and they involve experiencing a service firsthand. Invite colleagues to explore several end-to-end experiences (both your own and competitors) to record how well they can navigate across channels and touchpoints, what moments work and do not, and how the experience makes them feel. You can then look for patterns across safaris, as well as identify some potential opportunities for improvement.

Identify (and Get Close to) Your Internal Stakeholders

Better end-to-end experiences depend upon the right people in your organization aligning behind a common cause. But who are these people? Do they see the value in end-to-end experience and design? How open are they to collaboration? To make progress, you need to find out the answer to these questions while building rapport and trust. Here are a few tips:

• Create a stakeholder map. As detailed in Chapter 3, a stakeholder map visualizes the people, roles, and relationships of an ecosystem. You can use this method to visualize your internal stakeholders. These likely include channel owners, product managers, operational leaders, marketing managers, and many others. Leverage your company’s organizational chart and directory to start your discovery.

• Be a roadmap detective. Program roadmaps often list the owners of an initiative’s various projects and tasks. Many of these people may be relevant to your work. You may discover, for example, a marketing manager is involved in several onboarding projects that can help you understand marketing’s strategy for that journey stage better. In this way, roadmaps (and quarterly plans) can help you build out your stakeholder map and refine your plan for creating critical relationships.

• Meet and greet. Using your map, meet as many of your stakeholders as possible. You can use short 15-minute meetings (over coffee, for example) to put a face to a name. Share your intent of helping others work more effectively to help customers have better end-to-end experiences. Invest in maintaining and expanding this network.

• Ask about their goals and success criteria. When meeting stakeholders, ask directly what their current goals are and how their success is measured. For example, a mobile app product owner may be tasked with doubling the number of user accounts. The operations team, meanwhile, is expected to decrease call center handling time. Understanding these underlying drivers can help you identify common goals and conflicting priorities.

• Take a pulse check. Let’s face it, not everyone sees the value in designing for experience or collaborating in the manner outlined in this book. You should gauge your stakeholders’ openness to what you’re selling. A good tactic: as you learn their goals, give examples of how the specific orchestration methods can help achieve their goals.

Learn How Stuff Is Made

We all start somewhere. Maybe you are trained in interaction design but trying to get into strategy, or you have worked in digital your whole career but want to have a greater impact in other channels. Regardless of where you began or what you know today, you will need to get smarter on how different functions think and go about their work.

What does this mean in practice? You need to understand how stuff—products, services, processes, touchpoints, technological solutions, and so on—get designed and made in your organization. This involves learning both craft and process. For example, consider the CVS Target example back in Chapter 2. Here are a few examples of what you could learn:

• People: Are there a common set of principles behind how they interact with customers?

• Tools: How are work tools created to support employee tasks and the overall customer experience?

• Marketing: What is the process for defining marketing strategies? Who is responsible for making touchpoints in each channel?

• Software and technology: How do point solutions (such as adding register prompts or new applications) get made? How often are releases done? How long does it take to get modifications to software or technology platforms to get approved and executed?

• Physical environment: Who owns how a department is laid out and designed? What is their process for making changes?

• Processes and policies: How are different processes defined, documented, and implemented? Who defines policies and what are the processes for changing them?

Designing for end-to-end experiences becomes easier the more you know the answers to questions like these. It arms you with the knowledge to talk shop with collaborators, earning their trust and proving that you can understand and empathize with how they get their work done. You also become more effective in analyzing the value and feasibility of solutions outside of your core discipline. For example, you may know the ins and outs of digital product design and implementation, but now you understand the process that operations follow to implement changes to a physical environment or employee roles. Most importantly, this knowledge increases your ability to facilitate the design process within cross-functional teams.

Building your knowledge of how stuff gets made will happen through both experience and study. Our best advice is to ask lots of questions. Be curious about your colleagues and seek out ones who will share how they think about their work. The more you learn, the more dangerous (in a good way!) you will become.

Orchestrate Change

Throughout this book, we’ve intentionally used “orchestration” as a double entendre. In one sense, orchestration means holistically designing a system of moments, touchpoints, channels, and more. Orchestration, however, also applies to the process of collaborating with your colleagues. Instead of playing independently, you harmonize for the benefit of your customers’ experiences and your organization’s objectives.

Earlier chapters provided guidance on orchestrating the process to create your North Star. This section lays out four approaches for keeping the momentum as you scale that orchestration mindset into implementation and beyond. In concert, these activities—which we call experience orchestration—help increase visibility and encourage collaboration across multiple execution teams tasked with creating different touchpoints, processes, and other solutions. Experience orchestration can be a role, but works best when leaders and managers commit to working collectively to create more coherence and continuity within the customer experience.

Start Small

Once you have a vision, the more difficult work of orchestrating experiences begins— executing across multiple fronts with competing priorities while not losing sight of your vision. Don’t underestimate this challenge. It will take time to communicate the vision, build trust, align in-flight work, and try new ways of working across channels. You also will need to build confidence in management that this new paradigm will lead to better results.

For these reasons and more, start small. Below are a few options to consider. The common thread among them is changing small portions of the customer experience to be in alignment with your vision. These efforts can be accomplished in prototypes, pilots, or small experiments. In addition to helping you learn what solutions will work best, you will also forge new ways of working across teams that will pay off when you attempt a larger program of work.

For these examples, a fictitious installation service will be used to make these approaches more tangible.

Build a Bridge

End-to-end experiences are supported through many individual connections—touchpoint to touchpoint, moment to moment, backstage to front stage. Your North Star vision shows examples of critical connections, but these will take time to create. To start small, identify one or two new bridges that you can build. Figure 11.1 provides some common approaches to consider.

For example, a cross-functional team redesigning an in-home installation service might have a vision for personalizing call center, online, and in-home interactions. To start moving toward their North Star, this team focused on the bridge between capturing installation preferences and reviewing the personalized plan before installation began. The team also limited its scope to building only the connection between the call center and in-home channels (leaving other channels where preferences could be set for later phases).

FIGURE 11.1

Making one or two connections helps you test new approaches and build confidence.

Make a Touchpoint Consistent Across Channels

In some cases, you may want to begin by improving consistency of a key customer touchpoint that is delivered via multiple channels. Try to choose a touchpoint that, once changed, will have a clear measurable customer and business value. These types of efforts also help show the benefit of creating a common touchpoint architecture across channels.

In our installation example, design research revealed that customers were receiving conflicting and difficult-to-understand status messages in multiple channels. The team decided to tackle this touchpoint—learn my status—by defining common messaging standards, including language, timing, and frequency. They then partnered with channel owners to implement these changes for text messages, push notifications, emails, and automated calls.

Attack a Leverage Point

When you map end-to-end experiences, you often find a severe emotional low point that screams to be addressed. Fortunately, you now have the context of the full journey and your vision for improving it over time. In these cases, a good strategy is to address that low point first (see Figure 11.2), as this will improve the customer’s lasting impression of their entire end-to-end experience.1 The key is to do so in alignment with your experience principles and long-term vision.

FIGURE 11.2

Starting with the low point of an experience can alleviate customer frustration and improve their overall lasting impression.

Back to our installation service team. Call center complaints backed by experience mapping research had revealed that the moment of choosing what services and equipment to be installed was frustrating and confusing. These emotions carried into the rest of the experience, as well as cases of buyer’s remorse following the installation. The team chose to attack this moment. They created and tested concepts both online and in the call center, using their experience principles and vision for guidance.

Add or Resequence Moments

Because process design often dictates customer flow, you may find instances in which the sequence of moments does not optimally support customer needs. Similarly, your customers may have needs not addressed by any of your existing moments and touchpoints. A good place to start could be to experiment with rearranging the moments in a customer pathway or introducing a new stone in that moment altogether (see Figure 11.3).

FIGURE 11.3

Re-architecting with the sequence of moments.

For example, the installation service team prototyped in a service blueprint a concept for reimagining all the moments of the installation experience. This was a large endeavor, requiring new technologies, touchpoints, roles, and processes. To start small, the team focused on re-architecting the moments from just before the installer’s arrival through the service follow-up. Using a pilot in one market, they resequenced the moments following the installation, as well as added a new moment (with supporting touchpoints) prior to the appointment. The team worked within the constraints of what could be implemented and tested in two months.

Fake the Backend

Operational investments often dictate when (or if) significant improvements to end-to-end experiences can be made. New platforms, retraining employees, and redesigning business processes cost time and money. It also requires making trade-offs, such as deprioritizing other changes. To make a stronger business case, as well as learn to fine-tune your vision, consider starting with a pilot that fakes the backend. In this approach, you will test the key features and value proposition of your product or service, while working around current operational limitations.

In the case of our installation service, the team had envisioned a sophisticated customer relationship platform to collect data for use in tailoring interactions across channels. There were questions about this investment, and it certainly wasn’t going to be developed in the near term. The team decided to run a limited pilot partnering with the digital, call center, and installation teams (see Figure 11.4). The digital team would build a web form that some customers would interact with earlier in their journey. Instead of storing the data in a new system, an email would be sent to a call service agent. The call center agent referred to this information when following up with the customer, and then appended notes to the job record. The installer followed the current process of referring to the job record to prep for future appointments. Finally, the installer personalized the in-home installation based on this new information.

FIGURE 11.4

Faking the backend helps you test new experiences without waiting or building the case for significant changes to your operations.

Make a Rough Cut

Let’s return to the installation service example cited earlier. After making some progress with their pilots, the initiative team received funding to redesign the end-to-end experience. This would involve teams from digital product, technology, operations, customer service, field service, legal, marketing, and many others. Each function had its own way of defining solutions and implementing them. The digital product and technology teams ran Agile, but other functions still used waterfall. The marketing team outsourced production work to agencies. Program management tracked and reported the status of each project, but no one directed or reviewed whether all this effort would result in a great end-to-end experience.

This is a common scenario. In this environment, producing quality end-to-end experiences requires smart and effective collaboration. You (personally or with other team members) must continually provide execution teams with context and feedback, as well as listen to them and adapt your design as their work reveals new challenges. A tangible vision will remind everyone where you are headed. Your experience principles will provide a common language to inspire solutions and evaluate work. However, distributing these tools will only go so far in nudging all the work in the same direction. There are simply too many details and considerations to anticipate.

Filmmaking provides inspiration for how to engage and collaborate in a distributed execution team environment. While film is a linear art form, most productions do not shoot scenes in the sequence in which they will be viewed. This creates an economy of budget and time, but also creates challenges in keeping consistency in art direction and performance, as well as continuity across shots and scenes. After shooting early in the editing process, a rough cut is assembled to get a feel for the overall film, the sequence of shots, and the best takes to use. In animation, rough cuts are constructed regularly to see the status of each scene and the flow of the narrative. Some scenes are complete; others have temporary animation or sound. Regardless of how complete each part of the film is, seeing the pieces strung together as a story helps identify issues with consistency, continuity, and flow.

FILM AND EXPERIENCE

In helping organizations orchestrate experiences, I’ve taken a lot of inspiration from the art and craft of filmmaking. Filmmaking, like designing complex experiences, is a team sport. While producers and the director oversee the vision, budgets, and resources required to make a film, many specialized roles contribute to the final product. From scriptwriting, to costume and set design, to lighting and sound, and even the craft table that keeps the troops fed, hundreds of people can be involved. A film production is not unlike an army that decamps on location in a state of organized chaos. Along the way, thousands of decisions are made that contribute to a creative triumph or a forgettable failure, a blockbuster or a bomb.

Designing experiences that span channels and touchpoints shares many of the same challenges, and film production approaches can help immensely. Storyboards can be used to create concepts or to previsualize experiences. Rough cutting can help everyone see the work in progress and adjust accordingly. Continuity tracking will aid the identification of inconsistencies across moments. In concert, these methods help everyone understand the intended holistic experience that their individual efforts will manifest.

Creating rough cuts (or rough cutting) for end-to-end experiences is a great vehicle for gathering your collaborators and taking stock of what the result will be for customers. Like the filmmaking technique, a rough cut arranges an in-progress or completed work in a sequence that customers will experience. This should be done at regular intervals throughout execution, as well as after release to review metrics and plan future iterations.

The following is one approach for rough cutting with your colleagues. It assumes that you have created storyboards visualizing the moments that you want to create for customers. In the absence of storyboards, you can use simple scenario steps (on sticky notes), service blueprints, or other artifacts that provide an outline of the customer’s pathway. (Note: This is an in-person approach, but virtual sessions can also work if you can’t get people in the same room).

• Post your storyboard panels on the wall.

• Ask teams to bring their latest work. These could be mock-ups, requirements, sketches, screen shots, process designs, and so on—anything showing where they are in their process. It’s also helpful to have your touchpoint inventory handy to make sure that you cover all the parts of each moment.

• As a group, walk through the end-to-end experience. For each moment, remind everyone of the intent for the moment, as well as how it fits with the moments before and after.

• Review and discuss the different posted artifacts moment by moment. In our installation example, perhaps the mobile product team shares their latest sketches for requesting service, while the business architect shares the data model for a claim. Remember to refer to your experience principles to help guide and spark feedback.

• In some cases, the posted artifact may be a jumping-off point to review a working prototype or detailed designs in a document.

• During the review, participants should write down feedback and questions on sticky notes (see Figure 11.5). This keeps things moving, as you can save longer discussions for after the walkthrough.

FIGURE 11.5

A rough-cut walkthrough.

• All participants should be looking for opportunities to create better consistency and continuity in the customer’s journey. This could be language, interaction approaches, tension between process and experience, and so on.

• Finally, end the session with a review of decisions and action items. Commit to coming back together again. (Scheduling a meeting every two to three weeks is a good cadence for most projects.)

The dialogue during your rough cutting will reinforce teamwork, surface issues, make trade-offs clearer, and ultimately lead to better designed end-to-end experiences.

Lean into Your Journey Framework

When you observe how work gets defined, organized, and assigned in most companies, you see some interesting patterns. Three common ones that make orchestrating experiences particularly challenging include the following:

• Chopping up the funnel: Functions are organized around awareness, acquisition, onboarding, and servicing. Work happens independently, but each silo tries to influence the others to prioritize their dependencies.

• Product quarterbacks: Product management works as a federation of owners (or quarterbacks), often with divergent visions of the customer experience. In multiple instances, we have seen seven to eight product managers, with little to no coordination, who own different portions of the product experience.

• Operations-centric: Business process design—through value-stream mapping and various Six Sigma approaches—drives decisions on how customers (and employees) interact with the organization. As a result, product and service design are heavily constrained by these operation-centric architectures.

In each of these cases, ownership for what will become different stages, moments, or pathways of the customer experience is distributed. Each function creates plans to reach its objectives—create more awareness, reduce call center complaints, increase usage—but a holistic customer journey is typically not a shared objective. The resulting experiences reflect this fragmentation. Thus, an end-to-end experience has many masters, but no single owner.

This is beginning to change in some organizations. Jobs titled “journey manager” and “product journey manager” are cropping up in the U.S. and Europe. While their responsibilities are far from standard, these roles share a common intent of defining strategy and organizing work around the customer journey, not channels, technologies, or funnel stages.2 As the role spreads and teams are formed around them, our hope is that human-centered design will influence how customer journey management is practiced.

In the absence of this role, you and your colleagues will need to work together to increase focus and collaboration on the end-to-end experience. Your journey stages can be used as an organizing framework for spurring cross-functional communication, coordination, prioritization, and (eventually) strategy. Consider the following steps:

• Map projects to journey framework. A great starting point is to create visibility into all the in-flight or planned projects that will impact the end-to-end experience. Stakeholder conversations, roadmap reviews, and workshops are good ways to track down relevant projects. To communicate what you’ve found, use your journey framework to show which projects align with one or more of your stages and moments. Figure 11.6 shows this approach using storyboards.3

• Seize opportunities for collaboration. By showing the relationship of work to the customer journey, you can see opportunities for connecting efforts that impact the same stage or moment. For example, you may find several unconnected projects all working on improving onboarding, each with a different intent. This could result in a workshop to share insights, an experiment based on a common journey framework, or a formal project.

• Prioritize and plan together. Strategy is all about making smart trade-offs, given limited resources. To develop better end-to-end experience strategies, your journey framework can be used to facilitate cross-functional priorities. Using a similar matrix as a touchpoint inventory, Figure 11.7 shows one approach to visualizing these trade-offs.

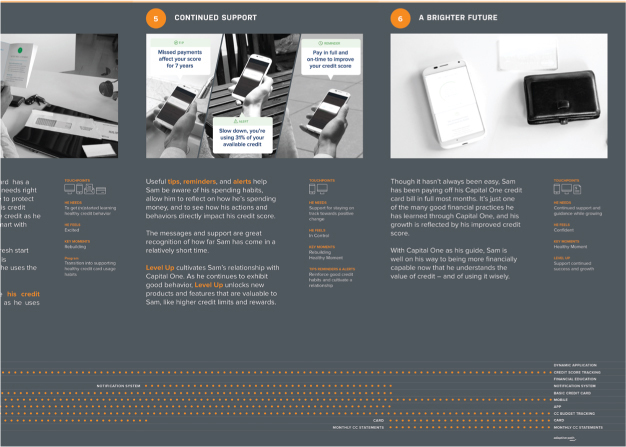

COURTESY OF CAPITAL ONE

FIGURE 11.6

Mapping programs and initiatives to moments.

DIAGRAM BY TYLER TATE, HTTP://TYLERTATE.COM/BLOG/UX/2012/02/21/CROSSCHANNEL-IA-BLUEPRINT.HTML. LICENSE AT HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0/DEED.EN

FIGURE 11.7

An example of communicating priorities across channels and journey stages.

Spark Change

Organizations are creatures of habit. You and like-minded colleagues must work to help others break the muscle memory of how problems are framed and work gets done. This change occurs interaction by interaction, project by project. Through hard work, infectious passion, and results, you can show others that there is better way.

Once you start making an impact, amplify your work as widely as possible. Tell stories. Invite others to play. Mentor or encourage others to take up the baton. As key leaders and other influencers join the cause, the change you want to see will gain momentum.

As your journey begins, consider these three approaches:

• Share stories. New approaches often get criticized by others as being too academic, too costly, or simply redundant. This resistance is partly fear of the unknown. As you create examples of orchestrating experiences, share them with others to demystify the process. This may be through case studies, presentations, or events. For example, at the close of a project, have your cross-functional team members invite peers to share how you approached the work and its outcomes.

• Train others. To create change at scale, you will need to equip others to work differently. This can start with informal or formal training sessions to introduce key concepts and methods. It’s important to be strategic when you determine whom to invite to training to spread experience orchestration more widely. Get people onboard excited to change the culture, not simply further their own agenda or personal brand.

• Make tools. Another effective practice is to make and distribute toolkits that guide others through using new methods. Adaptive Path took this approach to spread service design throughout Capital One. Through publishing a guide to service blueprinting and a set of supporting tools, they were able to touch hundreds of employees and equip them to try service blueprinting on their projects.4

• Build a community of practice. As more people get first-hand experience, these converts will help spread these new ways of working into their teams and future projects. It’s important to keep this excitement and interest building. Consider creating a community of practice to support one another and share progress. Simple tactics such as creating a Slack channel or regular lunch-and-learns can go a long way toward building momentum for more wide-spread adoption.

Start with You

In the beginning, you and others may have to stretch beyond your current responsibilities to influence your organization to adopt new ways of working. New roles, however, will eventually need to emerge to facilitate design orchestration. We have seen (and helped define) some of these roles for the organizations that we have worked with. Titles such as journey experience designer, cross-channel architect, end-to-end experience designer, service designer, and many others are becoming a bit more common. Increasingly, organizations will need these roles to step into the ambiguity of how to orchestrate experiences. Our advice: as you push into uncharted territory, don’t be afraid to label the new roles you play as their value is understood.

Positioning yourself to play a greater role in orchestrating experiences requires more than technical knowledge of concepts and tools. As you have probably noticed, a lot of this work involves guiding and collaborating with people from all walks of life, both inside and outside of your organization. These soft skills often separate good practitioners and leaders from great ones; they will be even more critical as organizations become more flat, matrixed, and (by necessity) collaborative.

Here is a brief overview of five key skills that you should work to build over time.

• Empathy: Empathy is more than a fashionable trend; it’s a critical 21st-century skill. Indi Young, in her excellent book on empathy, wisely notes that greater empathy can transform organizations, but this change occurs through people building their own abilities to listen and empathize with one another.5 Your ability to practice the methods of this book will be greatly improved as you sharpen your own empathy.

• Facilitation: Facilitating others through the design process requires confidence and skill. Seek out books, classes, and mentors to reflect upon and evolve your facilitation skills. Steal from the best, while developing your own style. You should approach this role as a service.

• Improvisation: You will run into many unforeseen challenges as you attempt to orchestrate experiences. A basic framework may not quite fit the context. A carefully planned workshop may end up being the wrong approach to get the job done. Approach these moments as a hurdle, not a wall. To get more comfortable thinking on your feet and embracing current conditions, consider taking improvisational theater. A good improv class will teach you to be more present, improve your listening and empathy skills, and tackle obstacles creatively as they arise.

• Storytelling: Earlier chapters reinforced the power of story in informing and inspiring others, as well as understanding and improving people’s experiences. Storytelling is an invaluable skill in today’s organizations, providing a critical counterbalance to big data and other approaches that can remove human context from strategic insights. Make it a habit to reflect on your storytelling approaches and look for new ways to expand your palette. Read books on the storytelling craft. Take classes. Most importantly: experience stories in all media and reflect on the techniques that make them work.

• Visual communication: It’s trite, but true: show, don’t tell. This includes sketching concepts, cocreating models with research participants, as well as visually communicating concepts in various artifacts. Whether you cannot draw a straight line or are a master illustrator, hone your visual communication skills. Take in-person or online sketching classes. Find a style that works for you to express concepts quickly. Push through the fear of drawing in front of other people. Be an advocate for visual communication and get people with great skills (who are often left out of strategic design work) deeply embedded into your project.

BUILDING EMPATHY FOR STRANGERS

I constantly get inspiration from all forms of storytelling to bring into my personal practice. Brandon Doman’s Strangers Project (see Figure 11.8), for example, invites people to share their personal stories as part of a curated experience toward creating greater understanding and empathy. I now use similar curated environments to make the stories of customers—and how to collect them through qualitative research—more accessible and impactful.

COURTESY OF BRANDON DOMAN AND THE STRANGERS PROJECT, HTTP://STRANGERSPROJECT.COM

FIGURE 11.8

Curating and sharing stories.

Take It from Here

Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report on birds written that he’d had three months to write, which was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.

—Anne Lamott,

Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life6

We believe the mindset of orchestration—of experiences, of touchpoints, of people—will create better outcomes for organizations and those they serve. It may seem like an enormous task to shift processes, habits, and cultures. We certainly see this as a long game. Yet, moment by moment, journey by journey, and initiative by initiative, you and others can create the change that you want to see.

Take up the baton. Play well with others. Make beautiful music together.