CHAPTER 6

Defining Experience Principles

Crafting for Adoption and Impact

CHAPTER 6 WORKSHOP: Experience Principles Refinement

If you embrace the recommended collaborative approaches in your sensemaking activities, you and your colleagues should build good momentum toward creating better and valuable end-to-end experiences. In fact, the urge to jump into solution mode will be tempting. Take a deep breath: you have a little more work to do. To ensure that your new insights translate into the right actions, you must collectively define what is good and hold one another accountable for aligning with it.

Good, in this context, means the ideas and solutions that you commit to reflect your customers’ needs and context while achieving organizational objectives. It also means that each touchpoint harmonizes with others as part of an orchestrated system. Defining good, in this way, provides common constraints to reduce arbitrary decisions and nudge everyone in the same direction.

How do you align an organization to work collectively toward the same good? Start with some common guidelines called experience principles.

A Common DNA

Experience principles are a set of guidelines that an organization commits to and follows from strategy through delivery to produce mutually beneficial and differentiated customer experiences. Experience principles represent the alignment of brand aspirations and customer needs, and they are derived from understanding your customers. In action, they help teams own their part (e.g., a product, touchpoint, or channel) while supporting consistency and continuity in the end-to-end experience. Figure 6.1 presents an example of a set of experience principles.

Experience principles are not detailed standards that everyone must obey to the letter. Standards tend to produce a rigid system, which curbs innovation and creativity. In contrast, experience principles inform the many decisions required to define what experiences your product or service should create and how to design for individual, yet connected, moments. They communicate in a few memorable phrases the organizational wisdom for how to meet customers’ needs consistently and effectively. For example, look at the following:

• Paint me a picture.

• Have my back.

• Set my expectations.

• Be one step ahead of me.

• Respect my time.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

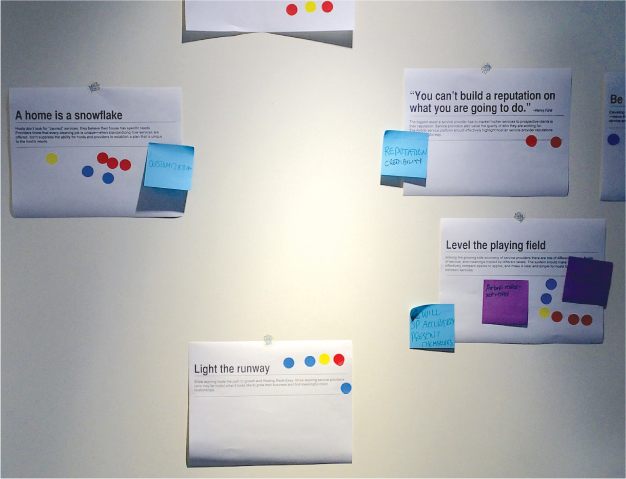

FIGURE 6.1

Example set of experience principles.

EXPERIENCE PRINCIPLES VS DESIGN PRINCIPLES

Orchestrating experiences is a team sport. Many roles contribute to defining, designing, and delivering products and services that result in customer experiences. For this reason, the label experience best reflects their value beyond designers and the design process. Experience principles are outcome oriented; design principles are process oriented. Everyone should follow and buy into them, not just designers.

Experience principles are grounded in customer needs, and they keep collaborators focused on the why, what, and how of engaging people through products and services. They keep critical insights and intentions top of mind, such as the following:

• Mental Models: How part of an experience can help people have a better understanding, or how it should conform to their mental model.

• Emotions: How part of an experience should support the customer emotionally, or directly address their motivations.

• Behaviors: How part of an experience should enable someone to do something they set out to do better.

• Target: The characteristics to which an experience should adhere.

• Impact: The outcomes and qualities an experience should engender in the user or customer.

FOCUSING ON NEEDS TO DIFFERENTIATE

Many universal or heuristic principles exist to guide design work. There are visual design principles, interaction design principles, user experience principles, and any number of domain principles that can help define the best practices you apply in your design process. These are lessons learned over time that have a broader application and can be relied on consistently to inform your work across even disparate projects.

It’s important to reinforce that experience principles specific to your customers’ needs provide contextual guidelines for strategy and design decisions. They help everyone focus on what’s appropriate to specific customers with a unique set of needs, and your product or service can differentiate itself by staying true to these principles. Experience principles shouldn’t compete with best practices or universal principles, but they should be honored as critical inputs for ensuring that your organization’s specific value propositions are met.

Playing Together

Earlier, we compared channels and touchpoints to an orchestra, but experience principles are more like jazz. While each member of a jazz ensemble is given plenty of room to improvise, all players understand the common context in which they are performing and listen and respond to one another (Figure 6.2). They know the standards of the genre, which allows them to be creative individually while collectively playing the same tune.

Experience principles provide structure and guidelines that connect collaborators while giving them room to be innovative. As with a time signature, they ensure alignment. Similar to a melody, they encourage supportive harmony. Like musical style, they provide boundaries for what fits and what doesn’t.

PHOTO BY ROLAND GODEFROY, HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:JAS_MESSENGERS01.JPG. LICENSE AT HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0/DEED.EN

FIGURE 6.2

Jazz ensembles depend upon a common foundation to inspire improvisation while working together to form a holistic work of art.

Experience principles challenge a common issue in organizations: isolated soloists playing their own tune to the detriment of the whole ensemble. While still leaving plenty of room for individual improvisation, they ask a bunch of solo acts to be part of the band. This structure provides a foundation for continuity in the resulting customer journey, but doesn’t overengineer consistency and predictability, which might prevent delight and differentiation. Stressing this balance of designing the whole while distributing effort and ownership is a critical stance to take to engender cross-functional buy-in.

To get broad acceptance of your experience principles, you must help your colleagues and your leadership see their value. This typically requires crafting specific value propositions and education materials for different stakeholders to gain broad support and adoption. Piloting your experience principles on a project can also help others understand their tactical use. When approaching each stakeholder, consider these common values:

• Defining good: While different channels and media have their specific best practices, experience principles provide a common set of criteria that can be applied across an entire end-to-end experience.

• Decision-making filter: Throughout the process of determining what to do strategically and how to do it tactically, experience principles ensure that customers’ needs and desires are represented in the decision-making process.

• Boundary constraints: Because these constraints represent the alignment of brand aspiration and customer desire, experience principles can filter out ideas or solutions that don’t reinforce this alignment.

• Efficiency: Used consistently, experience principles reduce ambiguity and the resultant churn when determining what concepts should move forward and how to design them well.

• Creativity inspiration: Experience principles are very effective in sparking new ideas with greater confidence that will map back to customer needs. (See Chapter 8, “Generating and Evaluating Ideas.”)

• Quality control: Through the execution lifecycle, experience principles can be used to critique touchpoint designs (i.e., the parts) to ensure that they align to the greater experience (i.e., the whole).

Pitching and educating aside, your best bet for creating good experience principles that get adopted is to avoid creating them in a black box. You don’t want to spring your experience principles on your colleagues as if they were commandments from above to follow blindly. Instead, work together to craft a set of principles that everyone can follow energetically.

Identifying Draft Principles

Your research into the lives and journeys of customers will produce a large number of insights. These insights are reflective. They capture people’s current experiences—such as their met and unmet needs, how they frame the world, and their desired outcomes. To craft useful and appropriate experience principles, you must turn these insights inside out to project what future experiences should be.

WHEN YOU CAN’T DO RESEARCH (YET)

If you lack strong customer insights (and the support or time to gather them), it’s still valuable to craft experience principles with your colleagues. The process of creating them provides insight into the various criteria that people are using to make decisions. It also sheds light on what your collaborators believe are the most important customer needs to meet. While not as sound as research-driven principles, your team can align around a set of guidelines to inform and critique your collective work—and then build the case for gathering insights for creating better experience principles.

From the Bottom Up

The leap from insights to experience principles will take several iterations. While you may be able to rattle off a few candidates based on your research, it’s well worth the time to follow a more rigorous approach in which you work from the bottom (individual insights) to the top (a handful of well-crafted principles). Here’s how to get started:

• Reassemble your facilitators and experience mappers, as they are closest to what you learned in your research.

• Go back to the key insights that emerged from your discovery and research. These likely have been packaged in maps, models, research reports, or other artifacts. You can also go back to your raw data if needed.

• Write each key insight on a sticky note. These will be used to spark a first pass at potential principles.

• For each insight, have everyone take a pass individually at articulating a principle derived from that insight. You can use sticky notes again or a quarter sheet of 8.5" x 11" (A6) template to give people a little more structure (see Figure 6.3).

• At this stage, you should coach participants to avoid finding the perfect words or a pithy way to communicate a potential principle. Instead, focus on getting the core lesson learned from the insight and what advice you would give others to guide product or service decisions in the future. Table 6.1 shows a couple of examples of what a good first pass looks like.

• At this stage, don’t be a wordsmith. Work quickly to reframe your insights from something you know (“Most people don’t want to . . . ”) to what should be done to stay true to this insight (“Make it easy for people . . . ”).

• Work your way through all the insights until everyone has a principle for each one.

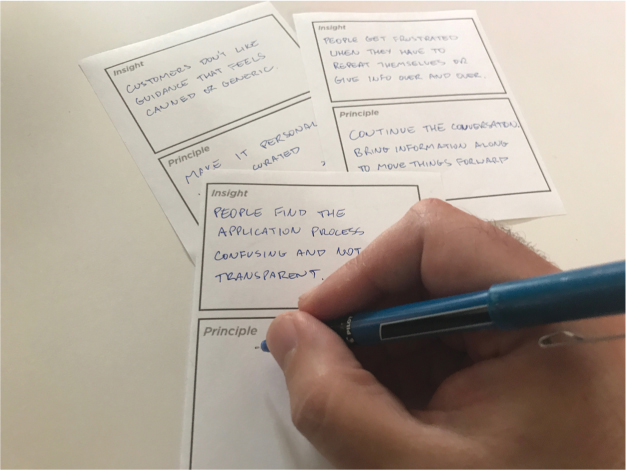

FIGURE 6.3

A simple template to generate insight-level principles quickly.

TABLE 6.1 FROM INSIGHTS TO DRAFT PRINCIPLES

Insight |

Principle |

Most people don’t want to do their homework first. They want to get started and learn what they need to know when they need to know it. |

Make it easy for people to dive in and collect knowledge when it’s most relevant. |

Everyone believes their situation (financial, home, health) is unique and reflects their specific circumstances, even if it’s not true. |

Approach people as they see themselves: unique people in unique situations. |

Finding Patterns

You now have a superset of individual principles from which a handful of experience principles will emerge. Your next step is to find the patterns within them. You can use affinity mapping to identify principles that speak to a similar theme or intent. As with any clustering activity, this may take a few iterations until you feel that you have mutually exclusive categories. You can do this in just a few steps:

• Select a workshop participant to present the principles one by one, explaining the intent behind each one.

• Cycle through the rest of the group, combining like principles and noting where principles conflict with one another. As you cluster, the dialogue the group has is as important as where the principles end up.

• Once things settle down, you and your colleagues can take a first pass at articulating a principle for each cluster. A simple half sheet (8.5" x 5.5" or A5) template can give some structure to this step. Again, don’t get too precious with every word yet. Get the essence down so that you and others can understand and further refine it with the other principles.

• You should end up with several mutually exclusive categories with a draft principle for each.

Designing Principles as a System

No experience principle is an island. Each should be understandable and useful on its own, but together your principles should form a system. Your principles should be complementary and reinforcing. They should be able to be applied across channels and throughout your product or service development process. See the following “Experience Principles Refinement” workshop for tips on how to critique your principles to ensure that they work together as a complete whole.

Crafting for Adoption and Impact

Defining a set of principles collaboratively with other people creates alignment, but crafting the language and presentation of your experience principles will fall on fewer shoulders. This detailed work is critical to ensure a broader understanding and adoption in your organization. Therefore, it’s important to spend the time and have the right skills handy to write and communicate your intent effectively.

Here are a few rules of thumb that we follow and recommend. However, it’s important to remember that every context is different. Use these as inspiration, not as hard standards.

Use a Consistent, Two-Tiered Structure

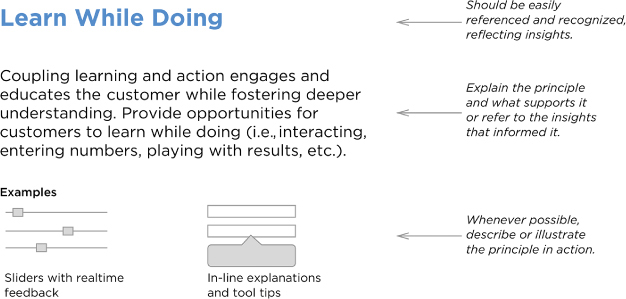

Experience principles need to be easy to recall and to use. As a system, it’s appropriate that all your experience principles share the same schema. We recommend a two-tiered structure consisting of a clear, memorable headline and supportive content to ensure that the intent is understood. In use, the headline is your short-hand principle, while the additional details put flesh on the bones. Figure 6.4 is an example of this approach.

FIGURE 6.4

Schema of an experience principle.

Make Your Headline Brief but Memorable

An experience principle should strike a good balance between brevity and clarity. One word, such as “guide,” doesn’t fully communicate a thought or inspire action. Too many words—such as, “provide me with the knowledge, tools, guidance, and people to help me succeed”—would be difficult to recall and is too specific to spark new ideas effectively. Strive for something relatively short but clear.

Good principles also have effective creative writing without crossing into cuteness or unintended ambiguity. “Be the Robin to my Batman,” may seem memorable, but its cultural specificity fails in terms of universal accessibility. On the other end of the spectrum, “support me” is too broad and less inspirational. “Always have my back,” however, clearly and memorably communicates important customer needs and emotions.

FIRST PERSON OR THIRD PERSON?

You may have noticed that some of our examples are in the Voice of the Customer (e.g., “Have my back”), while others are in third person (e.g., “learn while doing”). We have found both approaches to be effective and impactful. Experiment to determine what works best for your collaborators and culture. Whichever way you go, just be consistent—make them all first- or third-person, not a mixture of both.

Provide Supportive Details but Don’t Go Overboard

In addition to a brief, memorable phrase, supportive details help people understand the intent of an experience principle better. We recommend keeping this to one to three sentences. These should flesh out relative information regarding customer needs, emotions, mental models, behaviors, or the target experience. Follow the same rules as for your headline: your details should be clear, unambiguous, and easy to apply. For example:

Always have my back

I get uneasy if I think my best interests are not being protected. Clearly communicate that you respect my needs and incorporate that understanding into our interactions.

Avoid writing many paragraphs that explain the principle in detail. Too much detail risks crossing the line into being too prescriptive of a singular solution or specific product, service, or feature ideas. Flesh out your principle enough to make it easy to understand and useful, but don’t be overly prescriptive.

Design for Adoption

In addition to being well-written language, you will need to design multiple communication vehicles to ensure that your experience principles are integrated into your process and culture. Every organization is different, but the following tactics should give you some traction.

• Give examples of good and bad outcomes. Once crafted, your experience principles can be used immediately to critique current experiences or in-progress work. Hold some brown bags or more formal sessions to illuminate good and poor examples.

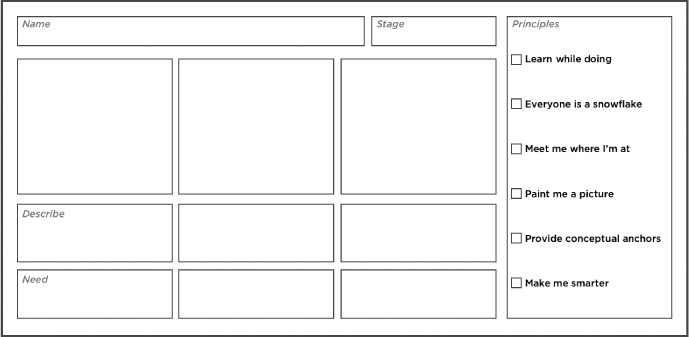

• Integrate into other deliverables. Experience principles should start to make their way into other artifacts, such as experience maps, opportunity maps, experience storyboards, and concept presentations (see Figure 6.5).

FIGURE 6.5

Experience principles are incorporated into a storyboard tool.

• Make contextual decision-making tools. It’s important that your principles are easy to use by different roles. Take the time to design tools for use during ideation workshops, in agile pods, design critiques, and other contexts. For example, you can produce experience principle scorecards for sprint demonstrations and retrospectives. Or you can build them into ideation kits for workshops or individual brainstorming (see Chapters 8, "Generating and Valuing Ideas," and 11, “Taking Up the Baton”).

• Pilot with some teams. Test out your principles with teams in different stages of the process from strategy to implementation. Insights can help you refine your principles and tools. Share their effectiveness more broadly to get others to begin using them.

CHAPTER 6 WORKSHOP EXPERIENCE PRINCIPLES REFINEMENT