CHAPTER 2

Pinning Down Touchpoints

Cataloging and Communicating Your Touchpoints

CHAPTER 2 WORKSHOP: Touchpoint Inventory

Example Pitch to Participants (and Their Managers)

The term touchpoint, along with channel, has slowly made its way into the lexicon of organizations primarily via the marketing function. Marketing traditionally creates a demand for products and services through campaigns targeted at customer segments. Campaigns often include several tactics—from commercials, to direct mail, to banner ads, and so on—which, in concert, increase brand awareness and offerings. Each customer interaction with a marketing communication is called a touch; the communication itself is a touchpoint.

Marketing organizations have become increasingly scientific in the creation, deployment, and measurement of touchpoints. Approaches such as customer relationship management (CRM) have enabled marketers to define strategies for how often they touch customers through which channels and to what end. New tools now exist for customer experience managers to monitor and measure the performance of touchpoints. Thus, the term touchpoint has become more prevalent in branding and customer experience to quantify and delineate the different ways that customers interact with a brand.

Other disciplines—such as service design—also focus on defining and connecting touchpoints. Interactions such as the attention and detail of a restaurant staff, the way your ride service driver opens the door or drops you off at the airport, or the literal quality of the touch by a massage therapist create the service moments in real time. Many touchpoints are intangible; for example, conversations can leave a lasting impression but are not objects manufactured beforehand. Services also create tangible evidence to reinforce brand or invisible actions. For example, a hotel may put a card and mint on your pillow to bring focus to and amplify the service of a nicely made bed.

What’s Service Design?

The digitization of products and services (as well as growing interest in customer-centered approaches) has led to the language of marketing, customer experience, and service design mixing with digital and physical product design. The term touchpoint has become more prevalent, but also less precise. Much of this ambiguity exists because practitioners within various disciplines use the same terms with slightly (or dramatically) different meanings. When one of your colleagues says touchpoint, she may be referring to a digital product (e.g., mobile app), feature (password retrieval), channel (email), or even a role (call center agent).

Orchestrating experiences requires coordination across different disciplines. Touchpoints represent fundamental building blocks of support for customer journeys that cut across time, space, and channels. Therefore, a common definition and approach to touchpoints can lead to improved coordination and ultimately better customer experiences.

A Unifying Approach

Here’s where things get tricky. To orchestrate experiences, you should think about touchpoints in two different but related ways.

First, customers encounter an organization, service, or product in a specific context. This encounter may be planned or unplanned; it may be designed or not designed. But they happen. You can observe the encounter, describe what is happening, and determine its effect. These encounters are touchpoints, and as branding folks will tell you, they will impact the customer’s perception of a brand, product, or service positively or negatively.

Second, organizations can design proactively for specific customer moments. They can determine the value that they want to provide, choose channels to interact with customers, and use design craft to meet customer needs optimally. These series of choices result in a family of touchpoints that are produced in advance or cocreated with customers in the moment. For example, a greeter at a retailer’s front entrance can be trained on how to greet customers while handing out a weekly specials coupon. The online store can welcome the customer with copy at the top and display the weekly specials below. The same touchpoint types—greeting customers and informing them about weekly specials—are delivered in different ways in different channels (see Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1

Greeting customers and informing them of weekly specials are touchpoints that take on different forms when delivered via different channels.

Touchpoints represent an important architectural concept in experiences that can span channels, space, and time. An organization can holistically craft an interconnecting system with a better chance of consistently and predictably meeting customer needs in many contexts. This system should be adaptable and extensible as new channels and interaction types emerge over time.

Such a systematic approach to end-to-end experiences requires creating more consistency in how touchpoints are defined within an organization. In the previous example, your colleagues may ask: “Isn’t the greeter a touchpoint?” or “Aren’t the weekly specials on the website a feature?” Yes, in the language of the separate domains of store operations and product management, respectively. But to orchestrate experiences, these differences in language must be reconciled. To this end, touchpoints can be defined as having the following dimensions:

• Have a clear intent based on identified needs.

• Create customer moments individually or in combinations.

• Play varying but specific roles.

• Can be evaluated and measured for appropriateness and efficacy.1

What’s Your Intent?

Touchpoints take different forms based on the channel, context, and interaction. An order status conversation with a call agent could be supported via phone, online chat, video, text message, or email. These touchpoints should share a common and clear intent behind their role in the end-to-end experience. They also should share a common set of principles that guide their definition, creation, and measurement. As Table 2.1 illustrates, product and service ecosystems typically have multiple channels—designed in silos—delivering similar touchpoints. Defining the underlying intent makes it possible to identify the same touchpoint types in different channels. This enables cross-functional teams to compare, connect, and increase the consistency of the superset of channel experiences.

TABLE 2.1 INTENT BY CHANNEL

Intent |

Website |

Mobile |

Call Center |

Store |

Greeting customer |

Welcome back copy |

None |

Enter phone number (IVR) |

Conversation |

Informing of specials |

Special callout |

Specials for you—push notification |

Specials message during wait time |

Coupon |

INTENT VS. EXECUTION

Separating the why and what (intent) from the how (execution in different channels) is important. For example, in my work with libraries, I have seen lots of experimentation in programs and approaches to bring new value to the community. Libraries, however, must still stay true to a pillar of their traditional mission: helping the community find information and build knowledge. As Figure 2.2 shows, the touchpoint of asking a librarian brings this mission to life in multiple channels based on an evergreen intent.

FIGURE 2.2

The touchpoint of asking a librarian is available in many channels with the same intent.

Making the Moment

The intent behind any individual touchpoint should not be determined in isolation. A touchpoint’s efficacy depends not only upon how it plays its unique role, but also how well the touchpoint connects with and conforms to the overarching experience. Because touchpoints can appear in different combinations in different contexts, it’s helpful to view them as role players in the customer moments you hope to create.

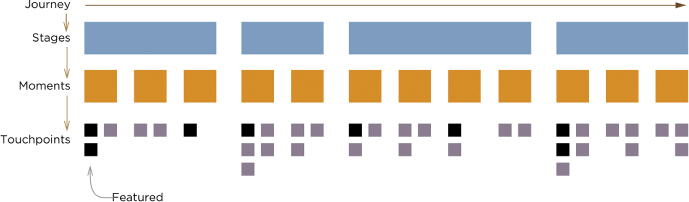

Figure 2.3 illustrates this conceptual framework. As customers move from moment to moment in their product or service experiences, different touchpoints support their journey. A few of these touchpoints truly serve as features, helping to create signature customer moments. Some touchpoints support specific customer actions. Others may play a more ambient role, while still others are called upon to serve a subset of customers.

FIGURE 2.3

Touchpoints appear in one or more customer moments, playing specific roles in each.

As an example, take the moment of checking in at the airport counter. Touchpoints in this customer moment include wayfinding signage, greeting and process conversations, mobile and print boarding passes, the baggage conveyor belt, and much more (see Figure 2.4). As illustrated here, touchpoints can be tangible (a sign) or intangible (a conversation). They can be analog (a conveyor belt) or digital (a mobile boarding pass). They can be manufactured beforehand (the check-in desk) or created in the moment (the length of the queue). Individually, each touchpoint plays its role; collectively, these touchpoints create the customer experience in the moment.

PHOTO BY KANCHI1979, HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:KOREA-INCHEON-INTERNATIONAL-AIRPORT-DEPERTURE-LOBBY-CHECK-INCOUNTER.JPG. LICENSE AT HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0/DEED.EN

FIGURE 2.4

Regardless of channels or who makes them, touchpoints should be orchestrated as one with the same underlying intent.

Different Moments, Different Roles

As you begin to rationalize the various definitions of touchpoints, it becomes easier to articulate the role and characteristics for each touchpoint. A few examples of touchpoint roles include featured, bridge, and repair/recovery.

• Featured: Not all aspects of a product or service uniquely deliver value to customers. Featured touchpoints play the role of helping create signature customer moments. Examples of featured touchpoints include USAA’s first-to-market mobile checking deposit touchpoint, Zappos’s easy returns, and Amazon Dash’s physical reorder button (see Figure 2.5).

FIGURE 2.5

Amazon Dash is a signature shopping moment with a beautifully designed enabling touchpoint.

• Bridge: When you want to help a customer move from one moment to the next or one channel to the next bridge, touchpoints are important. Some bridge touchpoints serve as handoffs (Figure 2.6), such as when one customer service agent dials in a second agent and gracefully transitions the conversation. Other bridges require two or more coordinating touchpoints. For example, a PDF concert ticket attached to an email, the ticket printed from your printer (another touchpoint), the door person asking for and recognizing your ticket, and the scanning of your ticket’s barcode are all touchpoints that bridge the moments from buying a ticket to seeing the show.

FIGURE 2.6

Bridge touchpoints (such as handoffs) often fall through the cracks as different teams focus solely on their own channel.

• Repair/Recovery: When customers fall off the happy path, repair and recovery touchpoints come to the rescue. If you can’t recall your password, you interact with “Forgot your password?” touchpoints. Or if you receive damaged merchandise, a series of touchpoints aid you in getting a replacement via your channel of choice. Repair/recovery touchpoints often have sequential characteristics to them.

These are just three of the most common roles that touchpoints may play. You’ll want to review your own moments and their respective touchpoints to determine what roles they play in your product or service experience. This becomes very helpful when you look at key moments through experience maps and service blueprints (see Chapters 5 and 9, “Crafting a Tangible Vision”).

Making Sure That Touchpoints Do Their Job

When you approach touchpoints as a coordinated system of featured and supporting players on the stage of experience, you naturally segue to the thought: “Is everyone playing his or her part, and well?” From a measurement standpoint, some touchpoints—especially digital ones—can be tracked and reported on. Examples include the following: shopping cart abandonment rates, email offer click-throughs, usage rates for mobile versus paper boarding passes, and how many customers upgrade a service following a conversation with a call center agent.

Other touchpoints can be evaluated by asking customers questions in person or via surveys. Was the entertaining airline safety video not so entertaining? How satisfied were you with the call agent’s problem resolution conversation? How would you rate your experience with our new packaging? This feedback can be used to improve specific touchpoints or flow among them.

As you will see in later chapters, great product and service experiences rely on orchestrating these good touchpoints well.

Two Helpful Frameworks

Touchpoints can be slippery. They take the form of the channels that deliver them, but work (or often don’t work) in concert to help create a customer’s experience. The same touchpoint—getting shipping status—can be offered simultaneously in different channels. Or a touchpoint can exist in only one channel. Understanding touchpoints, therefore, can require a couple of different (but helpful) frameworks:

• Touchpoints by moment

• Touchpoints by channel

Touchpoints by Moment

It’s a given that touchpoints play an important role in creating customer moments. They facilitate interactions, deliver information, trigger emotions, and bridge one moment to the next. Figure 2.7 illustrates a simple but powerful framework for placing touchpoints in the context of the overarching customer journeys they support.

• Journeys: Customers experience product and services over time, often in the context of achieving an explicit goal or meeting an implicit need (see Chapter 4). A journey, in this context, is a conceptual frame to refer to the beginning, middle, and end of the customer’s experience. Example journeys include going to the movies, saving for college, adopting a child, and a trip to the emergency room.

• Stages: A journey is not monolithic; it unfolds in a series of moments that tend to cluster around specific needs or goals. When mapping experiences, these clusters are known as stages. Stages are essentially chapters of the customer’s journey, which use a level of granularity for creating strategies that the common customer needs. Table 2.2 provides a few examples of journeys and stages.

• Moments: Whether linear or nonlinear, moments occur throughout a journey as the customers make their way forward in time. Not all moments are created equal, and the most important ones are often referred to as key moments or moments of truth. Regardless, all moments matter.

• Touchpoints: Touchpoints enable interactions within and across moments. As we’ll discuss in later chapters, defining a vision for each customer moment provides the right inputs for ensuring that each touchpoint plays its unique role while harmonizing with others.

FIGURE 2.7

Touchpoints represent fundamental building blocks in the journeys of customers as they interact with a product or service in multiple channels over time.

TABLE 2.2 JOURNEY STAGES

Journey |

Stages |

Going to the movies |

Exploring entertainment options, deciding what to see, going to the theater, buying a ticket, getting concessions, getting settled, watching the film, after the film |

Buying a home |

Searching for a home, getting prequalified, making an offer, applying for a loan, getting ready for closing, closing, moving, settling in |

A trip to the emergency room |

Experiencing a trauma, getting to the hospital, being admitted, waiting for care, getting care, recovering, paying medical bills |

To put this framework to work, you will need to determine the journey and stages you want to dig into down to the touchpoint level. Chapters 4 and 5 will provide guidance as to how to make these decisions with the critical input of customer research. However, starting with an informed hypothesis can yield good results. See the tips on drafting your stages and channels in the next section.

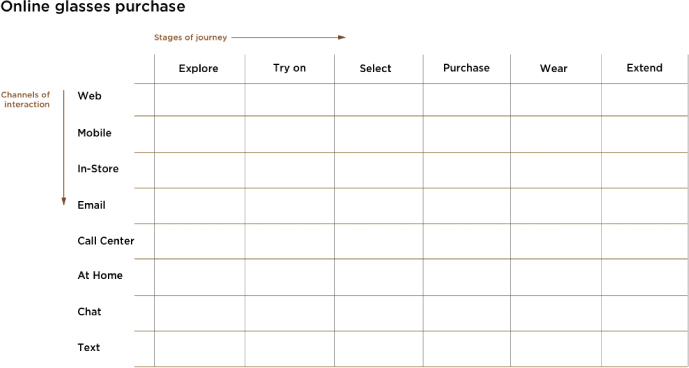

Touchpoints by Channel

Channels enable touchpoints, so it is also helpful to make sense of which channels deliver which touchpoints. However, simply viewing your touchpoints by channel loses the context of how touchpoints align to the customer experience. As illustrated in Figure 2.8, a simple matrix with journey stages on the X-axis and channels in the Y-axis creates a structure that keeps customer context top of mind. This framework—called a touchpoint inventory2 —also effectively provides an at-a-glance view of the density of touchpoints by channel and stage. The touchpoint inventory helps shed light on what touchpoints the organization has created and how they align—or fail to align—to the customer journey.

FIGURE 2.8

This simple framework organizes touchpoints by channel.

As with any framework, you will need to customize your touchpoint for your organization. If you are creating your framework in advance or in the absence of a well-defined customer journey, you will need to create an educated hypothesis of your channels and stages. See Chapter 1, “Understanding Channels,” for guidance on identifying your channels. As for your touchpoints, try one or more of the following:

• Bring together stakeholders that own various touchpoints in different channels. Collaborate with them to draft the journey stages that span all channels. (See the workshop agenda and approach following this chapter).

• Leverage any existing research you have on your customers, as well as the knowledge of your colleagues.

• Review business processes that customers must go through. Unfortunately, these processes may currently dictate where a stage begins or ends.

• Take your own journey. See how your experience breaks down into steps.

• Interview one to two customers to get a feel for their journey and its stages.

• Play with how many stages to divide the journey into. There is no magic number.

• Name your stages from the customer’s perspective, not business or marketing language. Instead of “creating awareness” and “consideration,” go with “researching and learning” and “exploring my options.”

Identifying Your Touchpoints

After you select one (or both) of the above frameworks to try, it’s time to get to work identifying all your touchpoints. This should occur in iterations. You can start by directly exploring each channel yourself. You can bring channel partners together to collaboratively build out a current-state touchpoint inventory (see the workshop example following this chapter). You will also discover more about your touchpoints (and even undiscovered touchpoints) when you conduct your customer research (see Chapter 5).

A QUICK-AND-DIRTY TOUCHPOINT INVENTORY

When Rail Europe wanted to better align its customer experience cohesively across channels, one of the starting points was identifying all the different touchpoints that existed where there was a specific need at a given time and place. We had everyone represented in the same room: marketing, digital, operations, call center, and more. Each stakeholder had a partial snapshot, but not a full view, one that reviewed interdependencies that they hadn’t considered.

When we completed a draft of the touchpoint inventory shown in Figure 2.9, each stakeholder was surprised just how many moments there were and how each moment was an opportunity to deliver on the value proposition of the service. We knew what stages existed in the journey, but across the organization, we realized no one had an exhaustive picture of just where people were interacting with the brand. The touchpoint inventory wasn’t a major endeavor, but it was an important one in getting everyone started with a clear picture of where the opportunity spaces were going to be as we later mapped out what people were experiencing on the rail travel journey.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 2.9

Rail Europe touchpoint inventory.

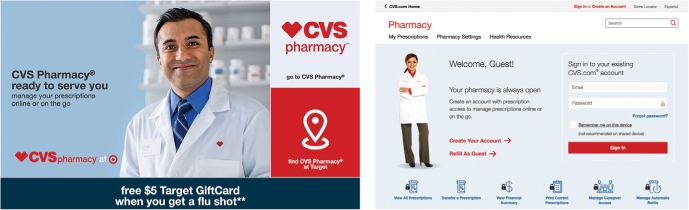

Let’s use our CVS Pharmacy at Target example again to look at how we might unpack a customer journey and its touchpoints by channel. This case study is interesting given the partnership between the companies (Target outsourced its pharmacy department to CVS following years of a well-regarded in-house approach).

To unpack each channel, you need to choose a method that works best for each channel’s medium while also identifying the stage or stages that each touchpoint supports. We’ll focus on identifying touchpoints for now. In the next section, we’ll give you some guidance on how to catalog your touchpoints as you find them.

Target Website and CVS Website

Publically accessible websites and mobile applications are often the easiest channels to begin your discovery. You can simply click or tap your way through each screen and state, capturing your touchpoints along the way. Digital touchpoints are often, but not always, equivalent to product features, and can even be articulated as user stories common in an agile development environment.

For example, starting at Target.com, you quickly realize that you must navigate from the Target website to CVS.com (see Figure 2.10). You do so via a bridge touchpoint. (An improvement would be an additional wayfinding touchpoint that communicates that you are still “at Target,” not a generic CVS.) Some of the CVS Pharmacy website touchpoints include: signing in, finding a pharmacy, transferring a prescription, printing prescriptions, and managing automatic prescriptions.

FIGURE 2.10

A bridge touchpoint (“go to CVS Pharmacy”) connects the customer to a site that provides a full set of online services.

In addition to exploring these online channels organically, you may want to try flowing through them by simulating a common user scenario or task. For example, you could search on Google for “get a flu shot at Target” and see what touchpoints begin to appear in your path.

CVS Mobile App

Like many brands, Target has created mobile applications designed to support customers shopping the entire store or carrying out tasks specific to its different departments. For the pharmacy, you must download the CVS pharmacy app. To avoid any confusion, we call this channel “CVS mobile app” while also including “Target mobile app” to inventory the bridge touchpoint. (As with Target.com, the main Target mobile app just simply points you to CVS.)

It’s easy to click through and see that many of the same touchpoints that are available on the website exist on mobile as well. As you click through, you will find that some touchpoints offer the same types of interactions as the website but others work differently based on the affordances of that channel. Refilling a prescription, for example, can be done by using your mobile’s camera to take a picture of the label or by typing in the Rx number, similar to the website (see Figure 2.11).

FIGURE 2.11

Refilling a prescription via mobile.

When doing your inventory, this is something specifically to look out for: How do touchpoints intended to meet the same customer need differ by channel? Doing so not only helps you understand if there are opportunities to meet needs in more channels, but also informs you of better ways to balance consistency and uniqueness across channels.

Physical Store

In a physical channel, such as a store, you can begin identifying your touchpoints as you did online by simply exploring. For Target, you can begin in the parking lot and find your way to the pharmacy. Is there signage or other wayfinding touchpoints to show you the way? Is there a store map? Are people there to assist? Are there pathways on the floor?

Observing customers and employees interact will also help you break down what exists in the space to support customer needs. Begin with building a list of the objects you see in the environment.3 Within a few minutes of observing service in a CVS Pharmacy at Target, you can observe these touchpoints (and many more):

• Wayfinding signage

• A drop-off area

• A pickup area

• An order conversation

• A status conversation

• A bin with filled prescriptions organized by letter of last name

• Pill bottles with labels

• A digital signature component

• Rewards program marketing signage

INTRODUCING TOUCHPOINTS TO OTHERS

I often make identifying and cataloging touchpoints a group effort. For example, on a service experience strategy engagement with a public library system, I tasked key members of the library staff to catalogue the staff, touchpoints, activities, qualities, and types of customers at different branches. Each staff member was given a template to capture what he or she discovered through observation and experiencing of the libraries’ services personally.

Distributing the inventory had several benefits. One was speed. We could pull together in a few days a great first pass. Just as important, the staff gained immediate experience in understanding what touchpoints were and which ones stood out in the current experience. By capturing them in a common template, my team was able to review and refine the inventory quickly. We then created a game (see Figure 2.12) in which participants determined which touchpoints to take into the future and what new touchpoints would be needed to serve customers better.

COURTESY OF RICHLAND LIBRARY

FIGURE 2.12

Playing with touchpoints and other elements that make up a current experience.

Phone—Voice

Many organizations provide voice channels supported by call centers or other means to sell, support, or deliver products and services. During your inventory, you likely will need to attack this and other communication channels from both the inside and outside to build a complete picture.

Let’s start inside. Hopefully, you can get access to your call center or other locations in which people speak directly with customers. In this channel, your touchpoints will be conversations. For our CVS Pharmacy at Target example, the nature of a call might have been to place an order, update an address, or check status. It could have been all those things. Your objective is to identify what conversations exist to meet these different needs.

Conversations as Touchpoints

If your organization has one or more call centers, they are a gold mine for understanding the needs and language of customers. Call centers are also complex environments in which changing the customer’s call experience requires equipping call center agents with the right concepts, tools, and training to deliver the intended experience. To understand the call center experience and the underlying processes, roles, tools, and policies, follow these procedures as much as possible:

• Listen to calls. Most call centers regularly record customer calls for compliance or quality assurance. Work with your call center team to identify calls related to the customer journeys or scenarios under investigation.

• Analyze transcripts. You can also read or search for key words in call transcripts.

• Ask for a report. Some call centers have sophisticated tools to analyze calls for key words and events. Try requesting a report (with audio clips) based on your needs.

• Perform side-by-sides. Call centers are typically set up for observers to plug in and listen to live calls. This is ideal for hearing the conversations and observing the environment and behavior of the agent.

• Process documentation. Process maps could clarify the flow of conversations and how processes trigger specific conversations. Be careful, however. Process maps often don’t reflect what’s happening on the calls.

• One-on-one interviews. Spend time interviewing agents to understand how they structure calls. You will need to keep these sessions to 30 minutes or less, as most call center managers are averse to taking their agents off calls for long periods of time.

• Current-state service blueprinting. This method is covered in Chapter 3, but consider doing service blueprinting sessions with agents to map how they work with tools and other employees to support customer conversations. Also, probe on what touchpoints the agents believe or know that customers interact with before and after their calls. For example, agents may have noticed that many customers call in after a digital touchpoint fails to meet their needs.

Other Channels

The methods we’ve outlined can also help you explore other channels. Target and CVS interact with customers via texts, push messages, physical mail, and email. In many cases, touchpoints are like voice communications—they may give status, prompt action, or connect to the next step. In other cases, they may contain unique touchpoints to that channel, such as a physical coupon.

Cataloging and Communicating Your Touchpoints

As you identify your touchpoints, you will need to document your findings. How detailed you get depends on the breadth and depth of your product or service, your goals, and the amount of effort you can (or should) commit to the inventory. You have lots of options, but your inventory should give people a complete picture of your touchpoints. Here are two approaches representing the two extremes on a spectrum from lean to finely detailed.

Keep It Lean

When you have little time, or just want to get a first iteration complete, your focus should be on nailing down the basics: stages, channels, and touchpoints. The Rail Europe example (see Figure 2.9) illustrates this level of detail. The stages should have clear labels in customer-centric language. It should reflect your primary channels, while less used channels can be summarized or combined. Touchpoints should then be organized at the intersection of stages and channels.

Figure 2.13 illustrates another approach on the leaner side of the spectrum. This inventory reflects a future-state vision of how to combine new and existing touchpoints into a better end-to-end experience. It includes specifications for each moment—required screens, content, and communications—to support the design process for different channels teams.

If you need to be even leaner and you have the wall space, build your inventory in sticky notes or take a picture of your workshop outputs and put up a large printout of it. Just make sure that your work stays visible to others so they can refer to it to inform strategy and design activities. Keep socializing the framework to unite others on its holistic view of where and when customers will interact with your product or service.

FIGURE 2.13

An example of a touchpoint inventory.

No Detail Left Behind

Beyond the basics, you can go much deeper into cataloging your touchpoints and describing their roles (and how well they play it) in the customer experience. This finely detailed approach is valuable in transformative work that involves reimagining customer journeys or creating sophisticated service experience architectures. While this takes time, the return on investment can be great in terms of better customer experiences and more easily managed operations.

A detailed inventory uses the same methods as outlined in this chapter, but with more information to collect and document. Like a content inventory, a spreadsheet tool provides the right functionality and flexibility to capture and analyze your work. You can then create different visual documentation with varying levels of information as needed. As Chapter 11, “Taking Up the Baton,” advises, your touchpoint inventory should be a living document for planning, creating, changing, and retiring touchpoints.

Below are common attributes helpful to capture and track your touchpoints throughout the design process.

• Channel stage: What stage(s) does the touchpoint support?

• Moment: What moment(s) does the touchpoint support?

• Touchpoint name: Make this clear and unique. If the touchpoint takes on different forms in different channels, keep the name consistent. For example, an Uber “ride confirmation” can be delivered via push notification or text message.

• Needs: What needs does the touchpoint meet? If none, do you need it?

• Roles: What roles—such as featured or repair/recovery—does the touchpoint play?

• Connections: If the touchpoint lives in a sequence or bridges to another touchpoint and channel, list those touchpoints here.

• Quality: Is the touchpoint good? Does it fail to adhere to basic heuristics or specific experience principles?

• Measurement: Do you have any performance metrics associated with the touchpoint?

• Owner: Who owns the touchpoint from the organization’s viewpoint?

• Status: Is there a plan to change or replace the touchpoint in the future?

Nailing down all these details can be a collaborative effort by leveraging shared spreadsheets to have people contribute across the enterprise. Together, you can create a living document of the architecture that makes your customer experiences possible. This foundation will then pay off as you collectively research, imagine, and conceptualize the moments and touchpoints of the future.

CHAPTER 2 WORKSHOP TOUCHPOINT INVENTORY