CHAPTER 9

Designing Healthcare Futures

Elena’s Story: A Change of Heart

Elena’s ablation procedure is clinically successful. The most difficult part of the procedure was lying flat on her back for 6 hours in postoperative recovery, a necessary precaution. Elena’s chest area feels sore and bruised for about 2 weeks, and she is instructed to avoid heavy work.

While resting at home, Elena finds herself back on some of the online forums she encountered in her earlier research. She visits MedHelp.com and finds dozens of responses to questions about SVT. She sees similar discussions at HealthBoards and eHealthForum. Several discussions have thousands of views and hundreds of threaded posts. Having time and a renewed interest in the problems, Elena is compelled to participate and post.

Elena had set up a profile on the site PatientsLikeMe during her earlier research and had posted a few times before the ablation. She was fascinated by the respectful discussions, the compassionate level of response to experiences, and the sense of caring. Returning to the community site after the treatment, she considers it worthwhile to post about her feelings and her personal impressions, and to browse the journals of people with similar disease profiles and treatments. A feature called InstantMe allows her to post a daily feeling, color coded from “very good” to “very bad” and tagged with a brief phrase. She clicks “good” for the day, but then adds “Sore and healing from ablation.” She updates entries for Quality of Life, and enters a few notes to describe Treatments (her prescription for bisoprolol).

Elena begins to see how the world of healthcare is changing at the level of patient engagement and peer interaction. She would never substitute the expertise of medical advice and clinical experience for the collected posts of other health seekers she does not even know. But there is a sense of community, mutual respect, and genuine caring among people suffering from the same physical misfortunes and emotional concerns. Elena may yet have to wait weeks or months to find out whether the clinically advanced procedure restored her heart and her well-being. But she finds the online circles of care a possible new mission for her future as a health seeker—helping others on their journeys to care and health.![]()

In the Adjacent Future

Healthcare is an enormous industrial, research, and practice sector with increasing job growth and increasing economic impact, as measured in national surveys. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the occupation with the highest job growth is nursing, with a projected increase of nurses from 2.75 million today to 3.5 million by 2020. According to the American Medical Association, there are 815,000 licensed US physicians. Including pharmacists, allied health practitioners (in nearly 60 professions), dentists, and administrators and staff, the US healthcare sector is the largest private employer. In many countries with public healthcare, it is the largest employer, with the United Kingdom’s National Health Service notably the largest public employer in Europe.

Hospital jobs were one of the few bright spots in employment during the recent recession: while more than 47 million jobs were lost, hospitals added nearly half a million new jobs. Although the big box healthcare model of large centralized medical centers has been faulted for sustainability, impersonal care, and wasteful expense, healthcare is often the largest economic and employment system in any region. Policy changes to the organizational and process structures of healthcare facilities could affect the jobs of many thousands. Policy innovation means cutbacks will happen somewhere in the sector, and every profession has a defensive strategy to prevent economic disruption, if not process change.

In 2011, futurist David Houle predicted that one-third of all US hospitals in operation would not survive to see 2020.1 The driving trends are considered significant enough to tip the sector into a phase of creative destruction. In this scenario, economic forces will force the hand of decision makers and policies will change by necessity. These trends include the following:

• Employer healthcare costs as a proportion of wages are extremely high ($12,000 annually) and increasing 10% a year. This rate is unsustainable.

• The performance of traditional hospitals has historically been poor if measured by the Hippocratic Oath standard of “first do no harm.” Estimates vary, but the Journal of the American Medical Association has reported 100,000 inpatient deaths annually, 80,000 of which originated from preventable hospital-acquired infections. The public is expected to wise up and avoid bad hospitals.

• Due to long wait times and poor customer service, hospitals will improve or die.

• Open data and connected services will provide the public with honest information about performance and value.

These are bold predictions, and their radical prescription predicts decentralized market-driven solutions. This transition is suggested as “inevitable,” but an experienced view of foresight suggests that the inevitable never happens the way we think it will. There is a high likelihood of healthcare costs destructively transforming the US institutional system as we know it. Many hospitals balance on the edge of sustainability at close to a 1% operating margin.

The business models of healthcare organizations will change to navigate these trends, perhaps not by ending operations but by creatively reconfiguring practices, organizational structure, and shared overhead. These challenges assume that large clinics may not have learned from their mistakes and that market alternatives may earn the public’s trust. Hospitals are already starting to decentralize, more due to the implications of Accountable Care Act policy than to market pressures. In fact, many hospital brands will strengthen. Large care organizations move slowly, require time to build consensus, and usually reinvent their own solutions to known issues.

Large-scale system innovation can be greatly accelerated when funding and values shift. In the case of big box healthcare, both have happened. The emergence of new community-based practice models has converged at the same time that many clinical leaders have called for values change. The patient-centered paradigm is rapidly becoming the new norm at many large institutions. At the same time, many traditional facilities are leading the way toward distributed, community-centered care centers.

In response to Houle’s claim, we might ask: “What will we call a hospital in 5 or 10 years?” If the big box model is already distributing into regional centers, we could see it becoming a constellation of storefronts with a big-brand, central, acute-care hospital.

Near-Term Design Challenges

What are the most critical service or system design issues we all face in healthcare? What problems should we focus on now? At least five “grand challenge” social design problems recur across the sectors (the whole system), none of which are healthcare IT or digital design.

• Redesigning care services: How can healthcare be reimagined and reinstitutionalized as a caring service? If the customers are a “market of sick people,” is it ethical to encourage this market’s further growth by creating new ways to help people identify themselves as being sick? Can health seekers and communities form durable circles of care to recover the meaning of care?

• Reenvisioning professional relationships: Have health professions created a self-serving system of professional services that converts people into patients? How can new service approaches enable patients to recover a sense of autonomy and choice in their health seeking?

• Working with multiple payers: US healthcare will be burdened with multiple market entities for the foreseeable future, and the trend continues toward market, not single-payer, systems. Here the treatment of disease and injury has been packaged for insurance, which hurts those who need it most. How might a systemic approach to service design reframe these offerings so that the consumer has the ultimate power of choice, not the provider?

• Health awareness and healthy societies: A healthy society emerges from individual health awareness. How can care service design educate people about the discrete and cumulative effects of choices and lifestyle results?

• Future position of healthcare: What if, over the next generation, the right to care was treated as a human right? How would personal and public health change to afford universal and inclusive care?

Design education and academic conferences are currently exploring these emerging topics (as well as conventional technology scenarios). A recent CHI conference workshop engaged current issues and shared common whole-system problems.2 Responses from more than 70 participants (consultants, academics, and representatives from private firms) identified critical themes and emerging issues at the whole-system level of healthcare. Responses for each question were clustered in four problem areas: management and policy, systems and services, design, and research (see sidebar on page 302).

Designers report struggling with the pragmatic issues of validating their contribution to the clinical workplace and appropriate technology design. One of the biggest conflicts is the acceptance of design thinking and practice in the evidence-based clinical and institutional setting. Professionals in differing sectors report issues with recognition of their value to the organization, difficulty in project collaboration, and limited access to clinical practice and patients for service and informatics design-oriented research. These organizational issues are perhaps barriers to collaborative innovation, but are not the primary systemic problems. A summary of trends and themes reveals:

• Management and policy issues are the most significant barriers to whole-system design.

• A strong focus on IT is often the focus for system-level design. This may not be the most effective means for design intervention in clinical practice. How can a service-oriented approach drive appropriate IT design and selection?

• A clear call is made for establishing systemic and integrated practices—interdisciplinary projects, design bridging groups, professional integration, multistakeholder engagement.

• Designers are seeking better ways to model, map, and framework the multiple systems, services, and data they deal with to help teams and organizations better plan and integrate multiple resources.

The workshop discovered that priorities and barriers involved both structural (policy, roles, and work practice) and organizational (process routines and management) issues. Organizational redesign is a primary aim of systemic design and organizational change, but not UX or services design.

Considering the precarious position of design teams reported within the current organizational culture, design-led approaches are not yet recommended (but may be practical after several years of practice development). In hospitals, multidisciplinary collaborations led by senior clinical staff with senior design partners would be the best route toward integrated organizational change. New leadership roles for designers and researchers will be effective in interdisciplinary practice research, IT project design and development, and service design applied to clinical offerings in the institution.

Mid-Future: Resolution of Critical Healthcare Problems

Canada faces serious headwinds as costs rise, as do all health systems. Although the single-payer systems of the United Kingdom and Scandinavian countries are held as examples of cost-effective healthcare, the burdens on funders are unsustainable. In the most recent Quebec budget, 45% of all provincial spending went to healthcare, up from 31% in 1980. The opportunities for business and policy innovation are compelling and necessary.

Canada’s federal government sponsored several healthcare commissions toward system-level reform and sustainability of their universal access Medicare system. In 2001, the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada recommended policies and measures to improve the system and its long-term sustainability. The subsequent Romanow report surveyed thousands of citizens and churned through statistics to produce an analysis and a set of 47 recommendations.3 Even though these recommendations were generated a decade ago, they remain current issues in policy and are considered long-term trends. They are well suited as mid-term to long-term trends for assessment in foresight.

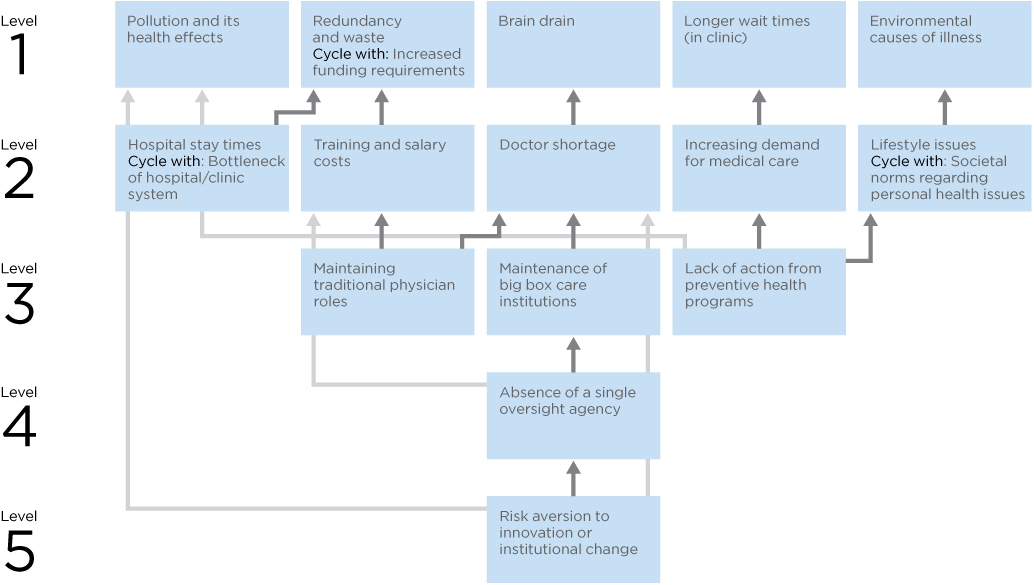

Graduate students from the OCAD University Strategic Foresight and Innovation program constructed an influence map analyzed from the Romanow report, showing the continuous challenges in Canadian healthcare.4 The diagram represents policy agreement on the significant drivers affecting costs and quality, most of which are applicable to the systems in the United States and other nations. Figure 9.1 shows the connectedness between the most critical problems as determined by their influence (revised by the author).

The graduate design research team produced the map using a dialogic design method (as defined in Chapter 8). The purpose of the mapping was to identify the highest-leverage problems that, once resolved, would propagate and resolve much of the connected system of problems.

FIGURE 9.1

Influence map of Canadian healthcare system issues.

Notice in Figure 9.1 that some of the traditional points of intervention to improve patient experience (based on an open source survey and experience) include “longer wait times in clinic” and “doctor shortage.” These points are convenient targets of action as they are observable and tangible, and resolution appears feasible. These also indicate the effects of deeper causes. Efforts expended toward these goals may not even touch the deeper problems. Because these appear at the top of the diagram, they are highly influenced, not influential. The pattern analysis reveals these are the resulting outcomes of multiple influencing causes, some of which appear in the lower levels of the diagram.

Working on the wrong problem perpetuates the cause and tends to shift the burden to another symptom. Many of the most common complaints in healthcare service, such as the shortage of family doctors, long wait times for certain specialists and procedures, and the ever-increasing costs of care, are the highly visible symptoms of overlooked (or delayed) systemic causes.

The influence map helps stakeholders visualize the complexity of the relationships among various issues in order to evaluate the problem system and make better decisions on actions that have the best “reach.”

With even a cursory evaluation of the deep drivers in the problem system we see a different story. The two deepest issues are “risk aversion to innovation and change” and “absence of a single oversight agency.” These drive up the costs of maintaining expensive existing institutions without regard to their actual efficacy in providing care.

At level 3, two other root cause drivers influence all of the level 1 and 2 problems, and thereby the rest of the map. “Maintaining traditional physician roles” and “lack of action from preventive health programs” are perfect systemic design issues that future practice scenarios could address.

We particularly examined how the blind maintenance of existing healthcare institutions might limit the possibilities for systemic redesign. Do the traditional professional roles of medicine (e.g., doctor, nurse, specialist) represent optimal functions in the system, or were they only reflecting a continuation of past institutional structures? What if the conventional one-on-one relationship of patient to family doctor was revisited? Would the system work better if it were organized around teams of practitioners with different skill sets? An expanded role for the community in maintaining public health was envisioned, a movement that is now gathering momentum.

Whole Care Triage Funnel

Ultimately, the analysis from dialogic design converged on three potential areas of intervention that required further consideration:

- The existing institutional norms that dictate the distribution of medical expertise among currently defined professional roles

- Individual versus team-based practice

- The role of the community in health

Powerful insights and future scenarios for system-level change emerged from these three proposals. A new paradigm for the organization of healthcare practices was envisioned for stakeholders using this method. The traditional role boundaries of the doctor as the single (and ultimate) bearer of responsibility for medical diagnosis should relax to enable shared roles in team constructs. Health services will increasingly be delivered outside the hospital system and into community or decentralized practices. Hospital visits will be minimized by increasing the opportunity points for health conversations initiated with immediate caregivers (and the community), instead of the often already critical and rushed centralized care facility.

Today the physician is usually the single point in the system through which all patient data and decisions must flow. A team system was envisioned to extend the triage principle through a “funnel” of increasingly specific diagnosis and responsibility. In traditional triage, patients are assessed as they enter the system, and they are given priority according to the urgency of their condition. In the proposed system, this initial assessment would merely be the beginning of a progressive triage focusing on multiple patient health needs treated as a whole.

In Canadian emergency rooms, a staged triage manages variable and high-volume workloads, where an incoming patient starts with a triage nurse, an emergency room or specialist nurse, or a resident, and is then treated by a senior resident or attending physician. The proposed “whole care triage” engages a physician’s assistant or nurse practitioner with diagnostic responsibility and the ability to call in supporting assessment and treatment.

The triage funnel works in two directions: broad community engagement and advocacy at the top, and increasingly specialized expertise at the point. Physician assistants mediate and filter out the appropriate cases before they enter the emergency room. Those that require specialized attention or assessment are passed down to the next level of the funnel.

The funnel introduces a process for organizational resiliency by distributing labor and expertise to the point of need, and optimizes the time cost of medical labor and workload. Other professionals and community advocates are given explicit locations in the process for participation. A wider range of caregivers are equipped to triage, assist, or advocate, enabling the time and capacity to translate patient needs and health requirements. As a result of this systemic process, patients with multiple chronic diseases are given progressive treatment respecting their total health, fewer specialists are utilized for emergency situations, and perceived emergency wait times are greatly reduced.

Similar processes have been put in place for large-scale emergencies (known as continuous integrated triage). However, these are based on efforts to manage resources, not to optimally treat patients with complex care needs. This triage funnel is similar to the proposal for iterative clinical care in the Innovate Afib case study in Chapter 5. By changing the purpose of the service system from internal resource management to patient-centered care, the triage process is repositioned as multidisciplinary guidance for complex care.

Longer-Term Healthcare Foresight

Designing for even longer-range complex design problems—10 or 20 years or more—requires practices from strategic foresight to account for the uncertainty and variation of possible trajectories of social trends and technology. Strategic foresight is not forecasting or future prediction, or as commonly thought, a design process of generating “future alternatives.” It is an art and research discipline of constructing possible formulations of future outcomes that enable better long-term planning and reasoning about risks in the present. It identifies trends and drivers from present culture that can be found to significantly influence possible future social and technological outcomes.

Strategic foresight consists of numerous practices for envisioning, reasoning about, planning, shaping, and designing future possibilities (Figure 9.2). It requires understanding current trends, ranges of choices, and anticipating change for strategic design and planning. Strategic foresight identifies emerging trends from technology and scientific research, emerging sociocultural and political trends, and global and economic policies for making sense of possible outcomes. Strategic foresight also attempts to translate trends in innovation (products, services, experiences, and systems) to align or lead the human needs and institutional changes among stakeholders.

FIGURE 9.2

Strategic foresight methods. (Adapted from R. Popper, 2008)

Foresight research fellow Rafael Popper organized methods from contemporary foresight practice to help practitioners select an appropriate balance of techniques.5 These are mapped by four dimensions and their evidence type—qualitative, quantitative, and what he calls semi-quantitative. The four points of the diamond indicate whether the method is a creative generative exercise or more evidence-based; or horizontally, whether an expert-based method or a collaborative practice. The diamond applies to clinical culture as a guide to both research and foresight methods, as it is currently heavily weighted toward evidence-based and expert methods. Integrating appropriate methods from the generative and collaborative positions into projects provides opportunities for collaborative teams to explore creative methods complementary to established evidence-based approaches.

Specific foresight methods are not detailed here, although many should be familiar from earlier chapters. Several social systems and emerging future methods have been incorporated into a revised model based on Popper’s diamond model (here replacing an equal number of methods).

Given the high social stakes and predicted costs of healthcare services in just the near future, the value of strategic foresight in healthcare should be apparent. Numerous “Future of Healthcare” projects are conducted every year by well-known groups such as the Institute for the Future and the Global Business Network, as well as design firms such as IDEO and PFSK. Not all future studies involve strategic foresight. Many future studies are conducted as “What if?” exercises in the possibilities of technological advancement or as speculation for design thinking.

One axiom of practice is that foresight research requires the investment of participants in the outcome of the future scenarios. The meaning of future possibilities and scenarios must matter to the design team. Professional futurist Joseph Coates lists three principles that underlie foresight thinking:

- We can see the future to the extent that it is useful in planning.

- We can influence the future to make the good and the desirable more likely and the undesirable less likely.

- The ability to anticipate and to influence creates the moral obligation to study the future.6

Ethical concerns arise in the “ownership” or personal commitment to healthcare futures, as human lives are at stake in the policy decisions and strategies chosen from these scenarios. It is an ethical requirement to consider all relevant stakeholder perspectives in future scenarios that have a wide social impact. Technological opportunities and breakthroughs do not determine the future of healthcare. The choices of leadership and engaged stakeholders determine the design of healthcare service systems.

One of Hasan Özbekhan’s early foresight axioms recognized that people allow technology to determine future outcomes, in that “Can Implies Ought.”7 He argued that just because we can develop a technology, the capability implied by that technology should not be implemented unwittingly. Innovation does not obviate the ethical demand to envision the possible future consequences and to fit the technology into appropriate service.

This necessity is an ethical requirement for designers, as well as managers, policy leaders, and citizens. This principle is crucial to ethical social foresight.

Two foresight design methods are explored in the cases that follow: three horizons and gigamapping.

Case 1: Three Horizons of Future Specialty Healthcare

Systems thinker and foresighter Anthony Hodgson’s three horizons is a method by which three overlapping time curves, or horizons, give rise to group thinking about the emergence of change over time.8 Three horizons can integrate multiple foresight and design scenarios within the context of sequential timelines, showing when and how trends and technologies might be integrated or fully developed. The method allows practitioners to relate drivers and trends to emerging issues, and links futures studies to organizational and social change.

A current case adopting three horizons was conducted by a team of foresight researchers working with the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation. The study, titled “The Future of Specialized Health Care Providers,” defined a complete strategic foresight model for the evolution of specialty care.9

Following a STEEPV (social, technological, economic, environmental, political, and values) trend and environmental scan, a trend map was developed and key drivers analyzed. Integrating other methods (cone of plausibility, wind tunneling, scenarios, backcasting), the study mapped trends, drivers, and barriers to the three horizons in near-, mid-, and long-term scenarios. Three robust strategies were identified for specialty care:

• Build a smart electronic health system.

• Integrate service delivery.

• Improve the patient experience.

These strategies were developed into their own three horizons timeline maps. The timelines indicate narratives for managing change to a preferred future state, represented by horizon 3 (H3), a patient-centric care system.

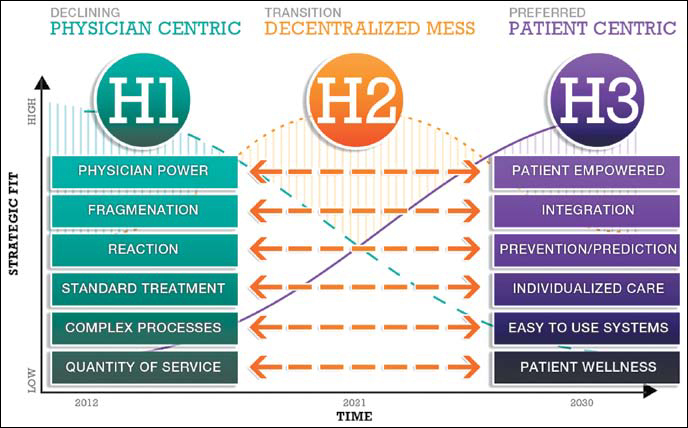

Figure 9.3 illustrates the major trend and shift from current practices in H1 to the “preferred future” practices in roughly 20 years (H3). The curves between H1 and H3 indicate the overlapping timelines and the change processes toward which stakeholders must attend in H2.

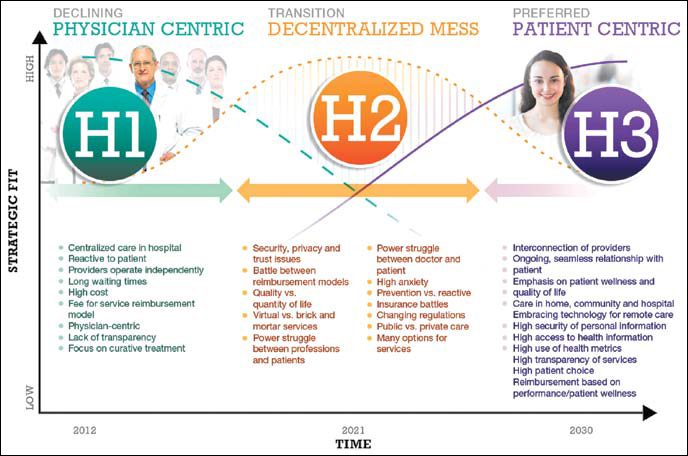

The study shows the dominant specialty care system declining over the next 10 years, during a transition state, as centralized (big box) healthcare systems reorganize a higher proportion of care in community and distributed practices. Figure 9.4 describes the tensions and concerns faced during the transition, yet there are “pockets of the future” throughout H1 in the next 5 years.

FIGURE 9.3

Three horizons of specialized medicine. (Courtesy of P. Sihavong, U. Maharaj, and J. Vink, OCAD University)

FIGURE 9.4

Challenges in horizon transition. (Courtesy of P. Sihavong, U. Maharaj, and J. Vink, OCAD University)

Weak signals recognized as indicators of new practice include the changes in patient empowerment as active health seekers, changes in payment, and the huge potential for integrated systems and services not being realized in current systems. Rapid changes in access to health information and online e-patients are prevalent indicators of the present that presage everyday future practices. Tensions between standard treatment approaches and the future potential of personalized medicine will be encountered and resolved during the H2 timeframe. The fragmented healthcare services and information systems will be forced to integrate over this period. These signal behaviors are not yet predominant values, but the potential for their trend to become driving values in new institutions becomes apparent.

For the purposes of the case, one of the three strategies is shown as integrated service delivery (Figure 9.5). Over the three horizons model, three scenarios play out between 2012 and 2030. H1 finds the healthcare system maintaining “business as usual” with incremental enhancements to service. As clinics across North America face a significant increase in baby boomer patients in the next few years, it makes sense to manage the demographic onslaught with predictable, known practices that minimize the risks of transition. Over the next 10 years, H2 practices (already in evidence) become widely implemented. Care teams, chronic care coordination, and whole-patient triage become common practices during the decentralization phase. These organizational changes are precursors to the establishment of integrated services delivery between 2020 and 2030.

FIGURE 9.5

Integrated service delivery across three horizons. (Courtesy of P. Sihavong, U. Maharaj, and J. Vink, OCAD University)

The emerging practices in H1—collaboration protocols, sharing information with patients, new roles for clinicians—are necessary improvements. But they are seen to evolve in H2 with more established processes for personalized patient case management and care coordination across multiple professionals, similar to that described in the whole-care triage funnel. Both of these horizons consist of incomplete innovations that enable specialized care providers and care teams to better coordinate complex patient care and collaborate on decision and planning.

Care planning is already a consistent practice in most acute and long-term care facilities. In many cases, care planning is recognized as the best opportunity for interprofessional dialogue on care strategies before significant treatment decisions are made. In the horizon mapping, care planning offers a platform for initiating collaborative healthcare, leading the institution toward integrated delivery. The future service system envisioned in 20 years consists of integrated EMR and information resources and fully transparent shared health records with patients. Clinical services will be collocated in communities, consistent with scenarios foreseen under the accountable care organization movement. Clinical networks will be organized under new management models of collective governance, giving all practitioners and patient/community health representatives a voice in healthcare investment and care practices.

The three horizons model provides a pathway for strategic planning based on foresight, enabling designers and decision makers to make sense of possible future outcomes. Although the service examples in this case are not radical changes, they are entirely plausible and will require years of learning and reorganization to be fully implemented. The strategic foresight methodology enables planning teams to envision these pathways and decision points, and provides a road map with which all stakeholders can engage.

Case 2: Intervening in Childhood Obesity

Systemic design based on systems thinking, evidence analysis, and visualization is a powerful approach for strategic foresight as it clarifies relationships in a system that occur over long periods. Future scenarios can be envisioned as with any foresight method, and interventions can be targeted to critical system functions that occur over a longer horizon. Gigamapping, developed at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design by professor Birger Sevaldson, offers such a visual thinking process and social systems design.10

Gigamapping is a visual representation that integrates classical systems diagrams (e.g., influence maps, causal loop diagrams, system maps) and visual thinking templates (e.g., timelines, infographics, rich pictures) into a pictorial narrative. The gigamap frames and describes both the problems and proposed interventions in a complex situation. A design team formulates the map over the course of research as its ever-present canvas, layering their evolving concepts and representations to show a narrative of the system story and its possibilities for design intervention. It analyzes the thick complexity discovered in research and presents a visual map of the salient, systemic drivers and solutions.

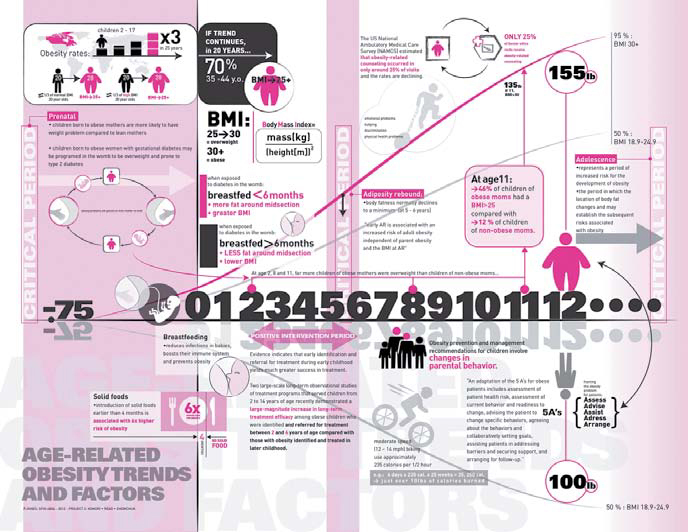

A design research team developed the system gigamap in Figure 9.6 as part of an investigation into systemic causes and interventions for childhood obesity.11 Childhood obesity, and individual and social health issues in general, is considered to be complex because the symptoms (effects) mask deeper causes, some of which may progress over long periods.

FIGURE 9.6

System map for childhood obesity intervention. (Courtesy of George Shewchuk)

The problem of obesity, a true epidemic syndrome affecting one-third of all adults in the United States and up to one-sixth of children, is a major systemic health problem of our time. Most efforts to address the wicked problem of obesity focus on dealing with behaviors to mitigate the effects—changing eating habits, inspiring regular exercise, and improving lifestyle behaviors overall. The gigamap simplifies the facts and data from evidence and presents systemic behaviors on a timeline.

The case considers the system of childhood obesity within the boundary of North American youth to the age of 16. The prenatal period was discovered as an extremely important window for determining or preventing obesity. The timeline also shows the relative increase in obesity (inclining curve toward higher weight) or decrease (declining curve) depending on factors illustrated at the different critical periods (shaded for emphasis).

A number of different system representations were necessary to organize a complete description of the system. Several map types were integrated here: a mind map, stakeholder analysis, causal loops, and an influence diagram. The history of the research process itself was also captured in the diagram.

The mind map helped identify the stakeholders and influencing factors, based on the literature. Stakeholder interviews and analysis clarified three points during a child’s life during which positive intervention could occur: the prenatal period, a spike in body mass index (BMI) at age 2, and then another period during ages 5 to 7. This information was presented in an influence map to identify the points in time at which different stakeholders play a role in the childhood narrative. For example, the mother and clinicians are most influential during the prenatal period, and school and media become influential only after age 5. Therefore, the level of influence and importance of each stakeholder in the system can be understood in relation to the time lag that dominates the system.

The effects of obesity ripple throughout society and the economy for generations; therefore, it is critical to evaluate the influences of stakeholders. Primary stakeholders are the child and his or her family, who constitute a first-order social system. The second-order stakeholders are educators, healthcare providers, government, and food providers. Third-order (indirect) stakeholders include community centers, special interest groups (e.g., ballet programs or sports leagues), and public programs such as parks.

A widely held view is that the best solution to the obesity epidemic is to focus on prevention and education to encourage healthy lifestyle changes. However, the social determinants of obesity are multifactored and affect all age groups and social strata. Interventions tackling individual determinants or narrowly targeted to one group of individuals will have a limited impact on a large scale and will not significantly reduce the magnitude of the problem.

Because of significant time delays within the total system, interventions targeting younger age groups are unlikely to have significant positive effects at the population level for many years. The cost-effectiveness profiles of such interventions may be favorable in the long term, but may be hard to justify during the contentious planning stages when programs and interventions are selected and budgeted.

According to some research, the influence of parents and the home environment is the primary determinant to setting the stage for healthy habits in children. Babies breastfed for less than 4 months have a much higher risk of obesity than other children. An intervention in mother-baby nurturing requires a change in behavior and a shift in priorities. The socioeconomic status of a family may determine the priority given to weight gain. Better nutrition takes more time and attention, and is less affordable than prepackaged and junk foods. Issues are compounded by an early lack of physical activity. This may be a result of a number of barriers that a family confronts, including the lack of financial resources to pay for participation and/or transportation to sporting events.

Although the most efficient interventions are found outside the health sector, healthcare can impact obesity and related chronic conditions by focusing on higher-risk individuals at stages when early obesity is identified. This factor suggests possible design interventions in the clinical setting to help new mothers identify the early symptoms of obesity and to introduce education and support for healthy diets and breastfeeding.

The visual description of the system of childhood obesity “system” helps stakeholders identify the best leverage points for interventions available to their resources. There are many other factors not illustrated here, but the selection of salient targets identified through research provides a basis for stakeholder dialogue and foresight over the 10-year horizon of the incubation of serious obesity.

Future Roles for Healthcare Design Leadership

This book presents three healthcare sectors found across the world: the consumer, medical practice, and institutional sectors. These three nested levels (which include education and community) comprise the primary touchpoints with systems of care. Several major sectors with significant design import were not included—IT, pharmaceuticals, insurance, and architecture. Although any of these sectors may today employ more design professionals than all clinical institutions combined, they are largely commercial entities and have employed designers in product and service roles for years. According to discussions with designers, there seems to be surprisingly little crossover of practice between the consumer and clinical sectors.

Achieving design leadership across these sectors will require a long-term engagement of design roles, not just the increased placement of design skills within IT, Web, and clinical service organizations. Leading roles are currently interaction (IT and UX) designer, service designer, design researcher/ethnographer, and communication (graphic) designer. Emerging placements include practice and management roles in innovation management, patient-centered research, experience design, and service integration.

Healthcare designer roles and tasks are not clear cut. Designers, ethnographers, and design researchers face a challenge in positioning their new roles in healthcare to make the most difference in health outcomes and business outcomes. New roles within established cultures will take time—a year or more—to fully socialize across departments and service lines. Design disciplines and skills may compete with or confront established norms in clinical culture. For organizations (hospitals and firms), discovering the best allocation of design talent will require trial and error, and experimentation across projects. Though some designers may be domain experts in a clinical field or in healthcare organizational strategy, most are not. The new value and values of design leadership will be co-created.

Consumer Health Sector

Throughout this book the roles of patient and consumer that we take for granted were critiqued and the person as health seeker was presented as a centering for design. For the sake of clarity, “consumer” is here, in closing, returned to the sector where it belongs. The consumer health sector is defined by its market and end-user products and services. These include IT (Web services, technology firms, start-ups), consumer products (personal health and consumable products), and health management services (wellness, employer health services, health insurance). The sector is defined by business-to-consumer offerings and is largely independent of the medical sector (clinicians as users) and the institutional (patients and stakeholders).

The majority of healthcare design roles are currently found in consumer health. With mandates to innovate and product revenue streams, commercial firms offer the promise of creative projects and bringing products to commercial markets, serving the health seeker as the primary customer.

The consumer sector carries the highest risks of product failure. With extensive competition and thin margins, consumer firms drive innovation by continuous product development. By some counts, there are up to 35,000 health apps in a widely distributed, fragmented marketplace. Given the interest in healthcare among start-up incubators, there seems to be consensus that consumer demand will follow. Yet the sheer number of single-purpose apps cannot be sustained. Within 3 years, the health app marketplace will consolidate, not expand. This cycle occurs with every technology surge and should be expected. Apps may be less expensive to produce than software or Web services, but they are expensive to maintain, update, and market over multiple platforms. Moreover, they are difficult to monetize.

Consumer-driven online business models may not be sustainable in the long term. Products, not services, rule the consumer health market. Web users do not pay for health applications; they have learned from Web 2.0 that free resources are supported by aftermarkets in user data. Consumer users will not readily pay for health apps when there are dozens of similar free services. (The same goes for physicians as users, who can afford subscriptions but will use free services plus their judgment to qualify the resource.) Advertising is a sustainable source for only the proven, popular sites and resources.

Among Web services, design quality is not yet a differentiator, indicating the field is still in early stages of adoption. None of the popular health sites were design leaders (although WebMD was recently redesigned and may have somewhat better usability). When consolidation reduces the number of viable services, design quality and usability will drive success among the preferred sites. Findability and content will continue to make more of a difference because health-seeking users tend to be intermittent, locating sites from searches and not assessing their relative quality from known sites.

The quantified self segment has emerged as one of the most vital developments in consumer health. The essential value of quantified self applications is converting biophysical measures of everyday behavior and physical activity into responsive feedback for enhanced performance in preferred activities. The availability of inexpensive data-acquisition sensors and durable activity monitors has reduced the barrier to entry for personal monitoring. As with classical disruptive innovations, the first products are directed toward a niche segment, in this case primarily amateur and professional athletes interested in measuring physiological performance improvements in physical activity.

The Nike FuelBand and the start-up Fitbit product use accelerometers to measure movement and track patterns, adapted to quantify energy exertion from walking and running, sleep patterns, and even caloric intake and output. Providing Web and mobile data exchange, the wearable devices gather data on an ongoing basis to track longitudinal patterns or training intensity for runners. Simple smartphone apps, such as the RunKeeper app that tracks running and cycling miles and times, encourage performance monitoring for defined self-health goals.

Portable personal feedback systems have been available for a decade or more in different forms and have been made significantly easier to use with ubiquitous mobile devices and Internet platforms. As a health trend, the quantified self will not necessarily be adopted by large numbers of followers; as a “movement” it is currently driven more by technology innovation than the need for health management. Yet the shift to wider consumer health might occur when small tracking devices can be prescribed by physicians and used for brief periods for health tracking and clinical feedback. As ultra-small sensors are packed into tiny wearable devices, massive amounts of personal data—from everyday activities and movement, to diet and blood sugar, to cardiopulmonary measures—can be tracked and synthesized into patterned displays for clinical decision making. Tracking feedback, responses to treatment and medication, and measuring adherence will make a huge difference in assessing the effectiveness of prescribed drugs and calibrating personalized therapies.

The consumer market for health services is so widely diffused that the consumer healthcare sector may be seen as many small sectors with their own followings and interests, with little crossover. Based on trends, the current and future consumer markets cluster into the following categories:

• Healthcare management and advising

• Personal health management

• General health, wellness, and lifestyle

• Medical diagnosis, treatment, and disease information

• Patient communities by disease or interest

• Medical devices, products, and information

• Health and beauty products and personal services

• Pharmaceutical products and their evaluation

• Nutritional supplements

• Health insurance and financing

• Employer-based wellness and health planning

• Clinician and hospital information

From a service design perspective, it is helpful to understand conventional market sectors as possible adjacent service lines. Yet from the health seekers’ perspective, the boundaries between services may be meaningless. If a nutritional supplement or meditation practice can ease a sleep disorder, the conventional categories of health “care” will not matter. Boundaries between consumer services are merging categories wherever the opportunity arises.

Clinical Practice Sector

Designers will find emerging opportunities for service design in healthcare practice and education, where complexity is high and the effect on improving patient outcomes is apparent.

Healthcare practices and therapies are constantly reviewed and researched for effectiveness, and their coordination for patient experience and cost management is receiving close attention from the business and policy decision makers. Design and systems research offer better ways to redesign care at the front lines in full partnership with clinical staff. Clinical design partnership works with interprofessional teams and provides access to real care situations for designing for clinical needs and directly improving patient experience.

Service design for improving patient experiences will become a mainstream trend, and the modes of design research and clinical research will converge as program effectiveness projects are enabled by design leadership. Patient-led service improvements and new healthcare organizational forms (such as the accountable care organization) will change our approaches to service design. Much of the design for patient experience is currently focused on big box healthcare and the enhancement of admission to discharge journeys, wait times, and the experience of care treatments. Even without a standard measure for patient experience, hospitals are rapidly adopting patient satisfaction surveys and incorporating patient-experience measures into their service quality reporting. Specialized clinics and group practices can be even more responsive, and managers and clinical staff are enhancing the direct experience of service provided to their patients. Design-led improvements are performed in very few cases, but the opportunities for design engagement are rapidly opening. In the course of the research of this book, the acceleration of new cases in the last 6 months outstrips the total examples identified over 3 years. There are many new stories of radically improved patient experience and clinical service.

Much of the push for better experience has been promoted by patients themselves, and by their advocates, nurses, and business services staff in hospitals. Though certainly stakeholders, those closest to the patients are not the decision drivers in the organization. Making the return-on-investment case for better patient experience is difficult because it is intangible and without standard accepted measures of merit.

Remember that patients have an unusual customer position in medical care, unlike any other service situation they will encounter. They have very incomplete knowledge of treatments, tests, and hospital procedures. The best “experience” might be the least experience. Large medical centers present risks that far outweigh a clumsy service experience. Doing no harm (or as sociologist Ross Koppel suggests, merely less harm12) should be the absolute baseline standard of care. This is not yet perfected by any means. Yet such a quantifiable assurance should be the patient’s primary concern.

Improving the patient experience is a primary focus for human-centered service design. Yet the end experience of clinical care is an effect of many causes. Focusing on the effects of care is not the most effective way to redesign the cause. Many factors that show up as better patient experience are end results like those in the influence map in this chapter (see Figure 9.1). Most of these are immediate and short-term touchpoints:

• Shorter wait times

• Easier hospital navigation

• Better room accommodations

• Attentive clinical and direct nursing care

• Simpler and easier payment processes

• Better physician communication

• Knowledge of all available choices, not just those prescribed

The systemic factors must be identified that result in consistently better care for health seekers undergoing a hospital service. These are nearly all longer-term management and education issues:

• Better procedure and process design

• Wayfinding that helps the infrequent visitor/patient

• Better housewide bed-management systems

• Clinical education that trains for empathic communication

• Education and practice modes for care teams

• Revamped insurance and Medicare policies

These are all interconnected design issues. Designing directly for better patient experience is indeed a care design problem, but it is not independent of these other factors. It is an outcome of care practices and can be used as a measure of improvement of these causes.

The solution for complicated problems of bed management or education may take much longer than direct redesign of symptoms, but this leads to repeatable and system-wide results. As practice research on hand-washing has shown, the everyday problems in practice are not resolved by verbal instruction or direct habit change. A fundamental change in the system is needed before the results of the change show up visibly.

Institutional Sector

Healthcare is the largest sector and business in North America, with 1 of every 8 Americans employed in the industry. And it is growing, both in dollar volume and population served. The institutional sector includes the clinical organizations, their business and policy ecosystem, practices of all sizes, universities, and medical schools. Think of this level as the employers, decision makers, and management for clinical practice and all the suppliers, IT support, and government organizations.

We have only a few short years to evolve a unique and developing role in the field before organizational routines may fold design roles into well-established, reliable, and repeatable design practices. Processes change slowly in large, rule-bound, risk-averse institutions. Before significant cultural change will be evident, designers will have to adapt to current practices while promoting innovation. Patience and a commitment to learning will be required.

At the institutional level, a service systems design approach is called for, given the complexity of operations, impacts to practice, and the integration with IT. There are several “grand challenges,” including:

• Formulating “triple aim” sustainable business models (financial, social, and environmental sustainability).

• Designing the transition to distributed community care.

• Designing the transition to ICD-10 procedure billing integrated with patient service.

• Information integration across technology providers and change management.

• Facilitating patient access to EMR records and health data.

• Managing transition to new practice models for chronic care.

• Leading and selecting appropriate innovation.

As the healthcare applications map in Figure 4.4 illustrates, clinicians have access to and use at least 10 classes of information tools for patient and house records, research and reference, clinical decision making, and practice. Most of these are complex applications requiring a user’s focused attention on information search and results for the purposes of analysis and decision. These applications are instruments of knowledge and policy that encode clinical practice and organizational routines.

Clinical services may be the primary end users of IT and information services, yet the information function is institutional and centrally managed.

Public-facing Web services, patient portals, EMRs, billing and coding, and patient satisfaction services are organizationally intensive central functions. These systems require the investment in user research and design for ensuring ease of access and use, productivity, safety, and business and community relationships. In practice, these are frequently developed and evaluated without significant insight (deep usability testing) from frontline clinicians or other constituents. Experienced design researchers in the clinical organization might start their tenure with interactive usability research as a way to make significant improvements rapidly and to expose the organization to evidence-based design research in health IT.

As more design-led innovators engage the challenges of this changing sector, a new challenge emerges to increase the cooperation and knowledge sharing across design and research fields. Currently, knowledge sharing is impaired by institutional secrecy, misplaced privacy concerns, and the scholarly approach to knowledge translation. Innovations are often reported in clinical journals and conferences, which require months of secrecy and peer review before being communicated. If both innovations and actual research findings are treated with the same internal protection and inability to circulate, it does not help institutions and practices learn from one another.

The current approaches to knowledge sharing are driven by evidence-based culture and the fact that clinicians are rewarded for publishing in peer-reviewed channels. This adherence to tradition is reinforced by the necessity to publish and teach; therefore, every successful project, even if highly practical, becomes a new research paper. With nearly 700,000 biomedical journal articles published each year, the medical corpus is vast beyond effective searching.13 Mere publication is not effective communication, as new articles become lost in the noise.

Community Context

A whole-system view helps us extend innovation beyond market segments (defined as customers) and reach people where their health concerns actually originate. All three sectors overlap a fourth context not considered a business sector: the local community where people live and participate. The community (a cultural region or neighborhood) is the primary context for public health, a domain currently characterized by health research, public engagement, and large-scale health interventions.

In the community context, health seekers are not isolated consumers with physical health issues (patients). People occupy dwellings and live in places that are more or less health enabling and are situated in communities that enable or discourage different social and lifestyle behaviors. Neighborhoods can be reasonably safe and socially engaging, or regions of uncertainty, social disharmony, and hazard. The social and lived experience a person lives within each and every day may be the most powerful determinant of health and risk.

Adopted social behaviors, such as smoking or poorly considered diets, may be among the most determining factors for health outcomes. Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler’s work on social contagion reveals the statistically significant health impact of close connections among people in geographically proximate networks.14 Their theory strongly suggests that people sharing similar locations and attitudes will adopt similar lifestyle behaviors that influence better health (happiness) or unhealthy habits (smoking, obesity, even depression). The theory and its support in public health projects show that systemic design (communication and program interventions) can influence the socially prominent influencers in networks and break unhealthy habits where they emerge and spread.

How might service and experience design treat the community as an object for social design? The most common examples are the community care services co-produced by residents as human services, which are not in the least consumer oriented. Circles of care are a well-known community care practice, providing support services such as transportation, errand running, and companionship for elders with regular health needs. Local food co-ops are a kind of caring practice, providing healthy food alternatives to local community members who share in volunteering. Soup kitchens and shut-in visitation are traditional forms of community care. Although these are grassroots community services, they are valued because they are authentic expressions of care that serve real human needs in the local community. Community participatory care can be considered the antidote to the consumer mindset and identity. People find meaning and connection in their communities, a source of relationship, and a source of healing or recovery from personal and family care concerns.

Several case studies in this book present community-level design concepts for reaching health seekers and caregivers within the community context. The Health Design Lab’s video documentary series of unscripted cancer stories described in Chapter 4 was developed as a public health communication artifact, sponsored by Cancer Care Ontario as a regional system intervention. The Innovate Afib clinical system redesign (Chapter 5) was conceived as a scalable (province-wide) system, but one that reached cardiac-risk patients within their local community’s points of access to the healthcare system. The Mayo Mom concept was specifically designed as a trusted local network sponsored by Mayo Clinic but delivered as an interpersonal service among mothers in their local regions.

The influence of the community on a health seeker’s experience and health cannot be overstated. Healthy communities can be considered the ultimate goal of public health and even medicine in general. The D4.0 approaches for societal transformation have only recently been articulated, and similar methods of social system intervention are rapidly being taken up around the world. The opportunities for the impact of social and systemic design thinking are limitless in the richly connected world of the community.

Innovation’s Adjacent Possible

The successful innovation—whether a product or institutional change—stands upon an installed base of applications and prior decisions and policies. It reaches a new boundary state compatible with the installed base of stakeholders and infrastructures. The next alternative, the near-future system state, is fully dependent on a preceding context—the social context and technologies that made the current state possible. Systems biologist Stuart Kauffman15 named “the adjacent possible” to describe the range of possible biochemical changes that any living system—a cellular state, an organism, its social states, and the biosphere—could reach without destroying its internal organization (or homeostasis). The adjacent possible applies to the nearest future opportunities for growth or innovation connected to present development.

Each sector remains coupled to its history and infrastructure, and each has differing adjacent possible states. Next-generation EMRs are not going to replace the installed base without first accommodating their data models and the base of expensively trained professionals. Medical education changes within a long period of institutional trials with pedagogy and technologies. Institutions change when they must. The changes triggered by service innovations may remain bounded within their sector and context.

Foresight views are not the same as innovation or direct design applications on real, current problems. Rather, building models of the long view helps designers and stakeholders make sense of possible configurations of the trends we all see and hear about. Design leadership has been nearly absent to date in the rational, modernist approach to care, IT, and organization prevalent in healthcare culture. Design-led innovation in the new multi-disciplinary practice provides a circle of imagination and human-centered knowledge that can advance care in novel ways. Design is the adjacent possible for healthcare innovation.

Conclusion

We have explored the possible territory for designers as members of integrated care teams, and for a new base of design skills and applications for clinical care, healthcare institutions, and deeply informed consumer healthcare. Designers are not considered professional caregivers—yet. Increasingly, designers in healthcare are situated and working beyond the known domains of IT, interaction design, and communications to bring human-centered design to clinical practice, service planning, and system-level prototyping. The necessity for highly qualified design in the healthcare enterprise is growing, certainly in major applications such as EMR interaction design, public websites and intranets, patient portals, and patient service experiences. As organizational managers recognize the value and return on compelling design and system usability throughout their organizations, interest will arise in adopting design processes for all types of complex problems.

Regardless of other organizational imperatives that may entail design skills, designing and improving technology for technical functions and everyday use serves a primary role that cannot be substituted by other skills.

However, the design disciplines are not a critical clinical function, and so they will not expand and succeed solely by way of executive advocacy. Design does not diffuse well by implementing top-down strategies, such as by hiring chief design officers or by executives evangelizing design to the clinical practices. The direct approach may be seen as competing with the highly contested terrain of IT, with skilled practice work routines, as well as with all strained budgets competing for other improvements. Also, in the healthcare world, outcomes are ultimately measured by the health seeker’s quality of life. We cannot always quantify design’s contribution.

We diffuse through organizations and projects much more effectively as creative developers of service concepts and products working on the front lines, while working toward the highest aspirations of the enterprise. Design as caring serves the discoverable opportunities for transforming work, organizations, and care experiences with radically better approaches to information, communications, and service delivery.