CHAPTER 4

Design for Patient Agency

Case Study: St. Michael’s Health Design Lab—Health Design for Self-Care |

|

Elena’s Story: A Personal Health Journey

Elena shows up at the family practice for her 8:15 appointment, but still has not reached any conclusions about her condition. She had spent over an hour browsing online the night before, jumping from articles on heart disease and healthy diet to blood pressure and stress management. Although Elena had hoped to be more informed for her visit, she was confused by the abundance of details about conditions for which she had little evidence or insight.

Her doctor’s suburban medical office is a group practice that serves as both a primary care and outpatient surgical center. Elena is welcomed by an office receptionist and is asked to fill out several pages of forms and interview questions. She is told that updated information is needed because the office is switching to electronic medical records. Elena would not have noticed the change in routine otherwise because the existing paper records are still taking up an entire wall of the open office area. Prompted by one of the questions, Elena retrieves her smartphone to look up the date of her last visit to the office. She has no personal health information stored on the phone or accessible through an app. Nearly all the information requested—from her medical history to the facts of her current condition—is duplicated on old paper and new electronic records. Yet Elena has no personal copy of her own records.

The primary care practice retains five physicians, four nurse practitioners, and six registered nurses, who either work in teams or are assigned to patients based on the procedures and clinical tasks required. Specialists and anesthesiologists are scheduled and on call for procedures as needed. The backstage management of clinical task assignments is handled by a medical director and coordinated by an office manager.

After an initial weigh-in, a nurse briefly interviews Elena in the examining room. He asks questions about her current situation and about her last appointment 5 months earlier. He takes blood pressure and heart rate readings, asks about current medications, and notes everything on a paper chart that Elena assumes is her medical record. Fran Martin, Elena’s family doctor, appears a few minutes later, now 25 minutes since Elena’s arrival.

Dr. Martin asks Elena about her symptoms and the reason for the visit, and listens to the account of the incident from the previous evening. Elena must admit to feeling well enough at the moment, having recovered her sense of normal health. Dr. Martin glances through Elena’s chart, performs a brief physical examination, and asks about prior incidents, other symptoms, and her diet and health habits. She orders blood drawn for testing as well as cardiovascular tests. Suspecting metabolic syndrome and the onset of diabetes as a diagnostic hypothesis, Dr. Martin orders glycemic tests and gives Elena printed handouts to read. A nurse preps Elena with 12 electrodes and gives her a brief electrocardiograph test. Still, Elena leaves the center without further insight into her condition.

Elena experiences a nagging sense of frustration and incompleteness. Although she has been “cared for” institutionally, she still falls short of having resolved her health concerns. As a caregiver to her father, she knows firsthand how complicated medical processes can get. And she remains unsure about how she can personally take charge of improving her own health. As a patient, Elena’s presence in the clinic signifies she has agreed to the social contract that confers rights on the physician and staff to examine and treat her under the customary conditions of healthcare. The professional arrangements, devices, measures, and controls at every step of the clinical process reinforce that she is “not in control.” Yet Elena is uncertain what steps she can take to help herself, other than adhering to her doctor’s orders.![]()

Self-Care as Health Agency

Elena has an unknown and abnormal health condition, and like most patients, she agrees to follow the standard care path by assenting to the traditional patient relationship. As more individuals choose a path of agency and become the decision makers for their health, a sense of disruption will grow in the healthcare system. Physicians say they want patients to take control of their health, but that means accepting the higher risks of nonadherence to traditional medicine and use of alternative self-treatments. An uneasy balance between patient and agent is already happening, led by new patient advocates on social media facilitating the transition to individuals taking control of their health agency.

A health seeker may cycle between being agent and patient and may never resolve 100% to either pole. In a serious health situation, a person will take action (agency) on matters of their choice and will also accept and seek care from others (patiency). Seeing the dynamics of choice and care in health seeking enables innovators to recognize that different communications, values, and incentives are necessary to meet the needs at service touchpoints.

How do we help people to help themselves? Does constant or incremental innovation in the simple services—online health management resources, health IT, consumer websites—address the societal and trend-level problems in healthcare? Better information resources are necessary and socially useful, but most IT systems and the personal health-oriented Web and mobile applications referred to as Health 2.0 are aligned to serve a single IT vendor or provider’s requirements. Health 2.0 and social websites may “scale” to serve any number of health seekers, but they do not scale systemically. Instead, they may lock in the prior commitments of the provider to a given strategy, preventing new systems from emerging.

The affordances of technology are a source for innovation. The trends in consumer healthcare innovation are driven by the increasing power and accessibility of cheap computing, and by ubiquitous wireless and mobile platforms. The health information ecology is constantly growing with a profusion of both professional content and low-cost, user-generated media. Yet two basic disconnects are exposed in Elena’s scenario: She has mobile access to information about her appointments, but not to health goals, prescription history, or test outcomes. And the physicians have installed a new electronic medical records system, but have no easy way to exchange this information with patients. Among the many disconnects in US healthcare is patient connectivity with health information.

Elena’s situation is typical—as people age, they often find themselves dealing with multiple interconnected chronic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Chronic disease situations are not cured, but are rather managed and “lived with.” As a growing aging population adapts to chronic conditions over longer life spans, designers have a major role to play in creating new tools for self-regulation and personal health agency.

Agents of Future Healthcare

People are taking charge of their own health in the 21st century by becoming “ePatients.” The ePatient movement was inspired by the realization among a growing number of activists that the digital information divide was an unethical institutional barrier to patients obtaining the most effective treatment. According to ePatients, the “e” not only stands for electronically enabled but empowered and engaged. ePatients are wired agents of their own care, and they represent the social future of healthcare service.

ePatiency started with the individual need for and right to medical information that might inform a person’s health decisions. Access to reliable and actionable health information has always been necessary for practitioners, and it is now becoming the case for patients. Since the advent of the Web, people have taken direct action by searching for authoritative medical research information for second opinions, and even first opinions. One of the earliest reported health information actions occurred in 1994, when Edward Murphy, a New Jersey insurance agent with a chronic hip problem, impersonated his family physician on the phone to a medical librarian to acquire a recent authoritative review article covering the procedure recommended for his treatment. Because his own doctor would not provide the article that Murphy had requested, he used social engineering to reach into the walled garden of publisher-protected medical articles. Today’s ePatients are just as provocative about patients’ rights, access to medical charts and personal data, and the rationale for procedures and medications. Statistics show that 57% of adults in the United States (2009)1 and 75% in Europe (2007)2 went online to inform themselves about a health question. In 2000, only 25% of US adults indicated that they went online for health information.

Advocates for personal health agency empowered by Web-accessible information may call themselves ePatients, but it’s not a patiency movement. If patient is a clinical designation for “healthcare user,” the ePatients initiative demonstrates the informed public’s frustration with the presumption of patiency—the expectation that people will take a passive and accommodating role under professional care. Activist and informed health seekers can, for the first time in history, collectively challenge the presumption of patient adherence to prescriptions, orders, and recommendations. Whereas physicians can research and inform themselves about one patient’s situation for only a limited time, ePatients may invest dozens of hours into researching a condition that informs their own well-being. Although access to health information remains unequal—even university research libraries typically restrict access to their expensive online medical journal subscriptions—articles of interest are searchable via PubMed in the National Library of Medicine’s abstracts.

Health Information as a Public Good

According to a 2009 Pew survey, half of all online health inquiries are intended to learn about a health situation for a person other than the information seeker.3 Furthermore, people readily share what they have learned with a spouse or friends, so the quality of information becomes a critical issue. Consumers may not understand the differences between information sources, and although some have the time or background to conduct thorough research into a health condition online, most information behavior studies show people find information that satisfices* their immediate question. Therefore, health seekers do not usually require original medical research articles, but prefer summarized information with sufficient guidance to inform personal action.

Satisficing enables people to make quick work of the Web’s ubiquitous access to an overwhelming volume of sources and references.4 It is the rapid sensemaking of information that helps people determine the criticality of a health situation. The slightest symptom sends people online in search of information—to distinguish between a cold and the flu, or to determine whether a brown spot on their back is a mole or a melanoma. The health seeker cannot be 100% certain, but can make a fuzzy distinction between the need to act or to wait out a physical process.

This type of fuzzy decision is characteristic of a sensemaking process (described later in this chapter as both a research method and a cognitive process). In sensemaking, the notion that people collect data, make clear decisions, and then act on them is exposed as a rationalist fantasy. In reality, people learn, struggle, and take actions oriented toward meeting personal goals. Those goals are not always rational and may be poorly formed, yet they initiate and bias information seeking and its use.

Scientists and intellectuals such as Harvard University Librarian Robert Darnton5 have declared open access to health and scientific information as a public good. Science and health research funding agencies are establishing new models of open information access with publishers, and open access versions of research articles are more often available. In theory, there seems to be a clear moral argument for the value of “open knowledge.” In practice, a vast ocean of poorly vetted, peer-written academic articles is not the best resource for public readers attempting to make sense of a health question. More is not always better, especially when the original information source was not composed for public use.

In activist discourses, the research articles are declared equivalent to “knowledge,” as if content were a direct transmission of wisdom from the scientific lab. In reality, the extraction of usable knowledge from research materials is a difficult process requiring extensive training (and is the rationale behind the growing field of medical knowledge translation). The public is largely unable to vet these contributions, which are written as peer communications to scholars who are assumed to have a background understanding of the precedent literature.

This translation problem exists across all scientific literatures, but it becomes vital when individual lives may benefit from timely uptake of the research findings. The situation of a well-informed and motivated health seeker such as ePatient Zero Edward Murphy is the exception. If health knowledge is a public good, then a new literature or new genre (at least) might be created for the public that references current opinion and evidence, yet is readable by nonprofessionals. The frontier of applied public translation has not yet been opened, even in the Health 2.0 movement.

Inspiring Agency for Self-Care

When the general public considers healthcare, their frame of reference draws on the strong association with professional health services. Even the political language referring to healthcare coverage and insurance reform has damaged the notion of care as a human value in its own right. Consider then the design challenge of encouraging public and individual health by inspiring design interventions for care. The most powerful intervention is changing the paradigm or the rules of the game. The most fundamental intervention is individual health behavior change, which will allow the paradigm change to unfold.

Innovation research by designer Hugh Dubberly and his colleagues Rajiv Mehta, Shelly Evenson, and Paul Pangaro promotes a systemic cycle of self-care resulting in a model of the person as sole agent for health responsibility.6 They radically repositioned patient-centered design (but not patient experience) by reframing the patient as agent. Responding to the growing problem that finds the vast majority of healthcare resources being consumed by chronic disease and later-life disease conditions, they identify a target outcome of shifting the system’s chronic disease system from patients of care providers to individuals with care responsibility (Table 4.1).

TABLE 4.1 SHIFT IN FRAMING FROM TRADITIONAL HEALTHCARE PROVISION TO SELF-MANAGEMENT

|

Traditional healthcare frame |

Emerging self-management frame |

Scope |

Relieve acute condition |

Maintain well-being |

Approach |

Intervention; treatment |

Prevention; healthy living |

Subject |

Symptoms and test results |

Whole person, seen in context |

Response |

Prescribe medication |

Improve behavior and environment |

Relies on |

Medical establishment |

Individual, family, and friends Social networks, others like me |

HCP as |

Authority, expert Dispensing knowledge |

Coach, assistant Learning from patients |

Patient as |

Helpless, childlike |

Responsible adult |

Relationship |

Asymmetric, one-way |

Symmetric, reciprocal |

Records |

HCP’s notes of visit |

Patient’s notes; data from sensors |

HCP = healthcare provider. |

||

The traditional frame can be seen as expert-managed and the self-management frame as patient-centered. We can view these frames as not true opposites but as continua with several dimensions, reflecting proportions of expert/patient responsibility. Figure I.1 illustrates the various stages of identity, care, and service encountered by a given persona over an extended period. As a person moves from a consumer role into a patient role, his or her responsibility for health management becomes unevenly shared. Healthcare providers accept more responsibility for the (now) patient as illnesses become complicated or serious.

Today, family and primary care doctors are largely committed to the self-management model of healthcare. Doctors on the front lines treat patients as people with a complex mix of health and life conditions, and serve in advising capacities during their consults. The future of primary care is moving toward the expert-coach, whole-person model of engagement. Family practitioners (an ever-dwindling proportion of new physicians) are trained in the tenets of a patient-agency frame in current residency programs, even if their home institutions conform to the traditional model.

The expert model predominates in acute care, which constitutes the majority of healthcare for people under age 60. Broken bones, acute infections, and eye surgery require expert acute care. Yet as people age and become subject to chronic continuing conditions, the burden for self-care becomes higher.* The need for patient education increases, even if that burden is met with reluctance on the part of older adults seeking symptom relief.

A mix of modes is needed when dealing with complex health issues, multiple conditions, and complications. A diabetic or cardiovascular patient may need to assume a proportion of 70% self-care versus 30% expert care. A surgery patient might need the reverse proportion. A design opportunity exists to create a common language between practice and patients to help all stakeholders distinguish the different types and degrees of responsibility.

Managing Personal Health as a System

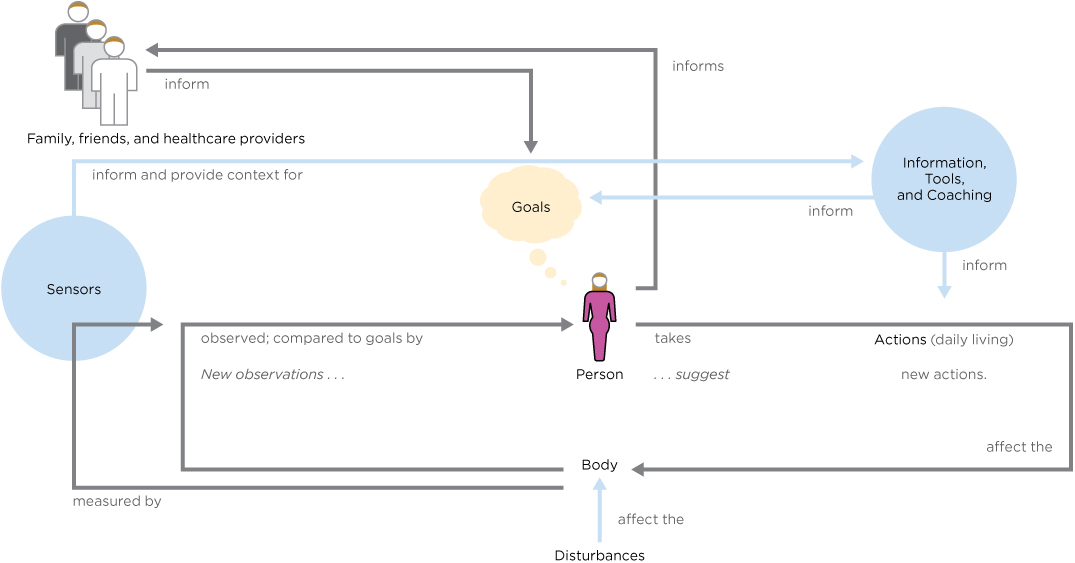

How do we shift the overall goal from healthcare as a service to personal management of one’s state of well-being? Dubberly’s model identifies an active cycle of identify, measure, assess, and adapt as a cyclic decision-management process (Figure 4.1). Health seekers inform themselves from sensor observations (feedback from devices and measures), information resources, and their social networks to assist in decision making.

FIGURE 4.1

An individual’s health self-management cycle. (From Dubberly et al., 2010)

How feasible would this method be? Biofeedback systems have been available for decades and provide for easily measured indirect responses (heart rate, skin resistance, brain waves, and blood measures). But the portability of mobile platforms and built-in multifunction sensors enables designers to easily display the values from health-sensing devices as mobile functions. The major feedback loop involves the health seeker’s body signals, sensors, and the change in state detected by senses or sensors.

Feedback cycles can be embodied in interactive artifacts (portable media and medical devices) and even electronic documents such as personal health records. Their self-management cycle is a continuous decision process, as Dubberly’s suggests, like the W. Edwards Deming and Walter Shewhart PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act) cycle.7 The PDCA cycle is a quality control practice often integrated into healthcare management processes at the macro level and is a key principle for service process design. Five steps are actually indicated:

• Assess a situation.

• Plan for change or adaptation by fact finding and identifying purposes and questions.

• Do the change or process intervention as planned.

• Check or study the analysis and summarize what was learned.

• Act or deploy the change or improvement (and plan for the next steps).

A wide range of PDCA resources are available on the Internet for health service applications, based on years of macro-level institutional applications.

PDCA is based on a management metaphor and does not translate well to the cognitive or decision-making level of activity. For everyday self-care management that requires less “planning and doing,” the tactical fighter pilot’s OODA loop (Colonel John Boyd’s cycle of Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) may apply.8 Drawn from a cognitive model of the situation awareness required for tactical air combat, OODA represents how one or more actors interpret and act upon a situation as it emerges. It defines a cycle of continuous observation and orienting to scan the environment and locate signals of importance. When signals (or bio-messages) are detected under the “orient” mode, a decision must be made. A decision is followed by action and then feedback about the effectiveness of the action. This loop cycle reinforces one’s self-awareness of discrete behaviors and the impact of health decisions on differing conditions. For example, a diabetic observes a series of measures, adjusts (orients) based on a glycemic value, decides whether intervention is required, and if so, acts.

The service designer will find that PDCA supports the requirements for cyclic feedback in service processes. Interaction designers should look to the OODA loop to create UX drivers for observing and orienting self-awareness. Today, the OODA loop is emerging in mobile application design in diabetes monitoring and tools such as Massive Health’s Eatery (https://eatery.massivehealth.com).

Mobile Personal Health

Although preventive health management is not a new trend, smartphone handsets and mobile interaction have given designers a new target. Health 2.0 technology is supplying tools to end-user health seekers that actively support general or disease-specific health awareness.

Consider how complicated everyday life is for the diabetic. Even with a state-of-the-art continuous glucose monitor and micropump, the diabetic must wrangle an assortment of products and tools needed throughout the week. In 2010, Italian designer Mauro Amoruso won the Diabetes Mine grand prize for Zero, his vision of a system that replaces the constant blood testing and injection ritual with a seamless wearable device communicating to a mobile display (Figure 4.2). Though not yet feasible, the concept represents an achievable target.

FIGURE 4.2a,b

The Zero concept includes an armband device (a) and personal information display (b) to replace the entire complicated mess of insulin management. (Courtesy of Mauro Amoruso)

The Zero armband is a refillable single-device concept that surpasses current technology and sets a target for industry to achieve. The smartphone display presents glucose levels and the ranges throughout a period of time, as well as insulin availability and dose, history, and expected impacts of food.

This interaction design concept accounts for several tasks associated with OODA. The graphical display allows a user to observe glucose levels (140 mg/dl) and orient by attending to the trend indicator (up arrow) and daily glucose measure graph. Decide (a cognitive step) and act are aided by the Zero’s five control icons (Setting, Glucose, Food, Send, Bolus). This monitor displays feedback from sensors embedded in the armband unit, which continuously senses blood sugar (by built-in cannulation) and injects insulin from a small reservoir to balance the glycemic system. The Zero system exemplifies the ideal for continuous health management and decision making.

While the miniaturization and mobility of computing has enabled designers to pack more functionality into smaller handsets and tablets, consumer sensors and physical interfaces have lagged. Large healthcare concerns such as Medtronic have been working on less-invasive diabetes devices for years. The goal of the designer here may not be to ensure feasibility but to aim for a functional and aesthetic solution that can inspire engineering innovation.

These emerging tools and the associated cognitive models share an underlying design theory that people are willing and able to affirmatively manage their own health conditions. The biggest problem with health management has been (and will be) patient adherence for the people whose lives are less conducive to sustaining healthy habits. Helping the already healthy is easy. Helping people who are not so inclined, and who may be the majority of patients in some regions, is our real design challenge.

Reframing the Patient as Agent

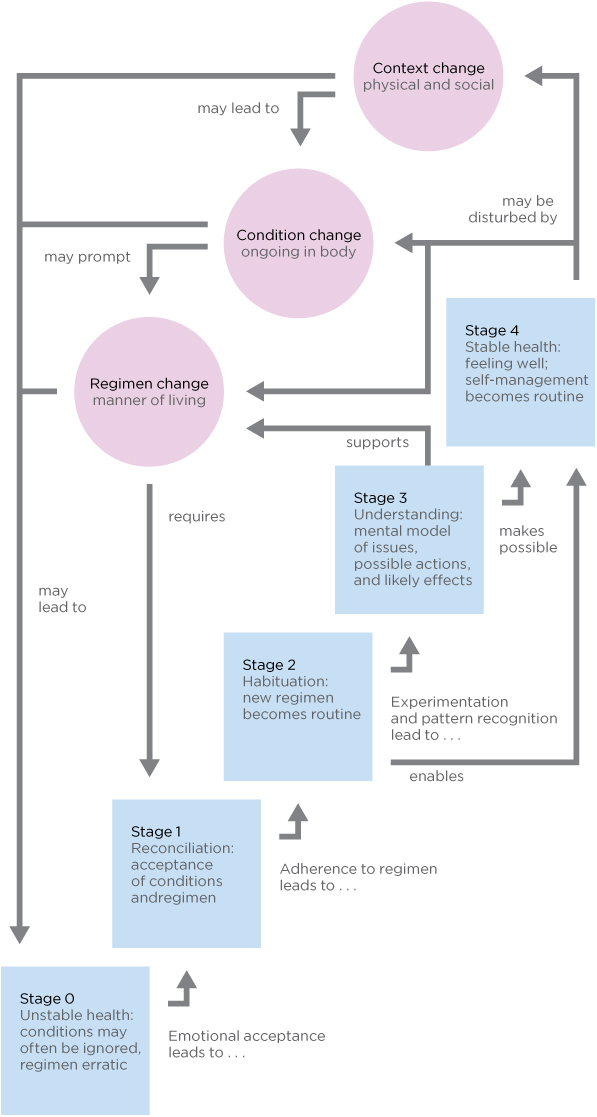

Dubberly and colleagues model the stages, states, and transitions in moving from patiency to agency through self-care management (Figure 4.3):

• Forming an initial positive personal health loop (stages 1 and 2) with reconciliation and habituation

• Reinforcing self-care (stage 3)

• Sustainably managing one’s health (stage 4)

• Participating in the contextual change that impacts larger social trends

Although the stages of self-care may appear to be a proposed “solution” to the wicked problem of improving healthcare for all, these are presented by the authors as scenarios for envisioning design proposals (the purpose of this book as well).

The first step of intervention in a complex problem is achieving understanding and reframing the problem. As a design thinking method, reframing creates a new problem frame and scope, an intentionality that establishes a new course of action. The intent guides new actions that route around the current problem system, rather than attempting to solve entrenched issues with insufficient scope and means.

Reframing creates a new context that can obviate the old way of viewing a problem. The context of the illegal practice of music downloading was reframed by the introduction of iTunes, a new service mechanism to encourage legal downloads at a pitch-perfect price point. Though stellar market success is not the intent of healthcare design, cultural change and new practices emerge in many cases from the reframing and the attempts to create new services that intersect and mitigate the existing problem system.

Consider reframing patients and users as health seekers. What system responses could be created to serve the needs of “people seeking health” as opposed to “patients under doctor’s orders”? The three versions of the health-seeking journey in Figures I.1, II.1, and III.1 represent the different motives, drivers, and touchpoints for different framing contexts.

FIGURE 4.3

Stages from self-care to agency. (From Dubberly et al., 2010)

Reframing lets designers focus on personal agency, with alternative scenarios of problem structure leading to vastly different approaches to problem “solving.” Scenarios are treated as design proposals, not as rigorous experiments. Prototypes of services and processes, as well as systems and interfaces, can be sanctioned and observed for systemic effects. Large-effect, relative differences can be recognized and reinforced. Successful programs can be scaled up to the next organizational level and evaluated with appropriate measures and techniques for the trial.

The staged process in Figure 4.3 is a macro-level scenario that, in some cases, may take years to accomplish. Dubberly’s team suggests using versions of health “dashboards” to display continuously updated micro-health measures to facilitate personal awareness of health status and progress toward the next stage. They promote the idea of displaying an integrated view of sources (e.g., health records, prescription data, narratives) and sensors (noninvasive physical sampling).

Health 2.0: Everywhere and Empowering

The simplest path to transformation is to declare that a new era has arrived. After the first wave of Web services recovered and rebranded itself as Web 2.0, health services followed (at about 2006) with an active bevy of start-ups and Web products. The Web 2.0 movement embraces user interconnectivity, activity streams, and information feeds from multiple sources, user-generated content production, and lightweight applications with rich interfaces. Health 2.0 apps adapted Web 2.0 technologies and development approaches to health information resources. Medicine 2.0 followed as a research and practitioner conference. Both trends are rapidly evolving into new directions of technology development, healthcare business models, and informatics research on new media in medicine.

The mutually reciprocal goals of patient empowerment and Health 2.0 both converge on tools for health decision making, personal information management, and helping people orient to well-being. The Health 2.0 movement has inspired new applications for user-generated content across all healthcare niches. Start-up incubators envision “interactive health” as the next major trend, and portfolio development groups such as Rock Health are focused entirely on health applications.

ePatients were among the first to take advantage of the democratization of user engagement and production enabled by Web 2.0 tools. The expanded reach of communicating and sharing ideas (blogging), community discussions (wikis and social networks), and user classification (tagging and foldering) shifted users from passive searchers to active participants. ePatients created the first health and disease communities and activist blogs, and institutional and commercial healthcare services followed only later. Health 2.0 is creating new interfaces and robust applications to facilitate wider societal access to these tools.

The Reach of Health 2.0 for Broader Impact

Health 2.0 has launched several important trends toward responsible self-care, personal data management (the “quantified self” movement), and patient advocacy (the participatory medicine movement). Health 2.0 maintains a strong view of the role of technology in enabling health, and is largely technology driven. We cannot yet describe statistically or even qualitatively the reach of Health 2.0 into the health, lives, and values of everyday health seekers. There may be hundreds of small markets across the Web for different niche health products, but the connection of small health-related technology start-ups to mitigating long-term healthcare issues remains unclear.

According to a recent article, the Silicon Valley start-ups heading up Health 2.0 products are creating apps for small, self-referential markets of early adopting technophiles.9 In other words, Health 2.0 trends like quantified self may largely be helping the already fit and healthy track their health, as part of the technology-obsessed 2.0 lifestyle. According to the article’s author, Kanyi Maqubela, the weakness of the Silicon Valley approach to Health 2.0 may be the lack of diversity, access, and business models for attracting the unhealthy people who need better paths toward improved health: “The quantified self and accompanying mobile health revolution needs to puncture markets which are usually invited last to the party. If entrepreneurs in this space are serious about making a difference, and about staying relevant to an evolving population, they need to invite these demographics first.”10 Maqubela recommends that start-ups work with healthcare incumbents, including government, pharmaceutical companies, and hospital systems, to improve their productivity in the larger healthcare ecosystem.

There may be several routes to scale applications at a system-wide level. Connecting to incumbents may be the fastest path to reaching large markets, but effecting change may be limited by the existing behaviors and values in that channel. Connecting directly with health seekers through social networked communities may take longer, and the resulting community may not be as vulnerable to market intervention or regulation. Most Health 2.0 applications are not (yet) facilitating care through provider networks. Moreover, once a patient has committed to a platform, they will be less likely to expend resources interacting on other similar networks.

The highest-impact Health 2.0 application, PatientsLikeMe, creates social care by engaging qualified patients in peer exchange and the aggregation of personal data for evaluation and comparative analysis. PatientsLikeMe also helps organizations by making that data available for treatment and outcomes research. Yet it has only (roughly) 165,000 registered “patients,” many of which are inactive. This is a huge membership for a Health 2.0 community, perhaps the largest. However, compared to the overall healthcare market, Health 2.0 reaches only a tiny proportion of possible patients. Kaiser Permanente’s HealthConnect patient platform claims 8.6 million members.

Practitioner advocates view technology as secondary to the change in practice and patient engagement. Physician Scott Shreeve encourages practitioners to embrace the emerging opportunity to disrupt healthcare practice and policy by combining technology innovation with business and practice changes to create a virtuous cycle of innovation. Shreeve’s definition of Health 2.0, although not universal, has broad acceptance in the United States: “A new concept of healthcare wherein all the constituents (patients, physicians, providers, and payers) focus on healthcare value (outcomes/price) and use competition at the medical condition level over the full cycle of care as the catalyst for improving the safety, efficiency, and quality of health care” (emphasis added).11

The most compelling thrust of Shreeve’s orientation to Health 2.0 is to focus innovation on service system change, not applications. The technology marketplace has since aligned with the functional perspective of changing healthcare delivery and information by adapting tools and practices from Web 2.0. The technology view is gaining ground, supported by the annual Health 2.0 conference, through lionizing start-ups with incubators such as Rock Health, and even by trademarking the Health 2.0 label.

Practitioners and scholars working in the high-touch clinical field have assigned Medicine 2.0 to the practitioners, including the trademark and conference. The original definition of Medicine 2.0 is technology-focused and even identifies the constituents of the healthcare system as user groups:

Medicine 2.0 applications, services, and tools are Web-based services for health care consumers, caregivers, patients, health professionals, and biomedical researchers, that use Web 2.0 technologies as well as semantic web and virtual reality tools, to enable and facilitate specifically social networking, participation, apomediation, collaboration, and openness within and between these user groups.12

A systematic review of the published and online (gray) literatures13 reveals 46 unique definitions of Health 2.0 and Medicine 2.0, but says that the two schools seem to have converged around seven recurrent topics:

• Web 2.0/technology

• Patients

• Professionals

• Social networking

• Health information/content

• Collaboration

• Change of healthcare

The review authors concluded by fusing the two terms together as Health 2.0/Medicine 2.0 and declaring the field as a still-developing concept, which is strikingly similar to the narratives emerging from both camps.

Health 2.0 started with patients, not start-ups, adopting relatively simple Web tools—wikis, free blogs, video sharing, online community services—using off-the-shelf tools to build specialized portals for communicating with other patients and providers. Technology enablers preceded the “user need.” The adoption of generic tools (such as WordPress, used for health blogs like Diabetes Mine) preceded the development of the commercial services (such as Alliance Health) that often follow entrepreneurial innovators with sustainable support.

Online engagement is not health care. Scaling thousands of users online does not scale service for thousands of patients. Although patients can be superficially examined remotely, physical examinations are done in person. Medical advice must be given in a context of understanding.

Start-ups are easy to launch but difficult to sustain. Hundreds of online healthcare products will consolidate to dozens (or fewer) sustainable ventures. Beyond Health 2.0, the next frontier will be transformation of practice and direct service models, driven by the largest-scale factors current generations have ever known:

• Population: aging demographics with complex chronic conditions

• Costs: rapidly increasing societal cost burden as demographics shift

• Technology: new biotechnologies, information technologies, and medications creating increased demand

• Life span: expansion of lifetime costs as global populations gain more access to healthcare and live longer

Health 3.0: Inclusive and Communicative

While Health 2.0 apps and Web services are being developed for consumer and business-to-business applications, the major health IT (HIT) vendors have delivered enterprise applications for hospital and healthcare systems of any size and scale. Chapter 7 presents cases and lessons from some of the largest implementations of electronic health and medical records (EMR) systems currently installed. A spectrum of thousands of software systems exists in the categories between the single-user Web app and the enterprise EMR. Information technology has become an active partner, even a team player, to support human care in the processes of care service delivery.

Even a quick sweep of the HIT landscape shows significant differences between the emerging Health 2.0 applications and enterprise vendors. Health 2.0 is almost entirely composed of Web-based or mobile applications, a bottom-up profusion of mainly single-purpose software applications without significant platform development. Their advantages of user focus, nimble adaptation, focusing on a single problem, and rapid iteration follow the disruptive innovation playbook. Their strategies work best with target markets of smaller enterprises, healthcare industry corporations, and individual users.

HIT systems are primary-vendor, platform-driven, large-scale software systems based on government and industry standards and designed for highly structured workflows. Nearly all primary vendors are providing for end-user interaction and distribution through Web (thin client) user interfaces. Most EMRs are currently providing interfaces for tablet and phone-based mobile apps, based more on industry trend than healthcare service need.

HIT services are becoming true platforms that allow organizations to capture patient and transaction data as enterprise assets. HIT enables distribution and exchange through critical standards such as HL7 (Health Level 7), an ANSI-certified standard for data exchange between vendor systems. HL7 provides a standard basis for defining and sharing any healthcare document, or any hospital, lab, or imaging report, using the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) specification.

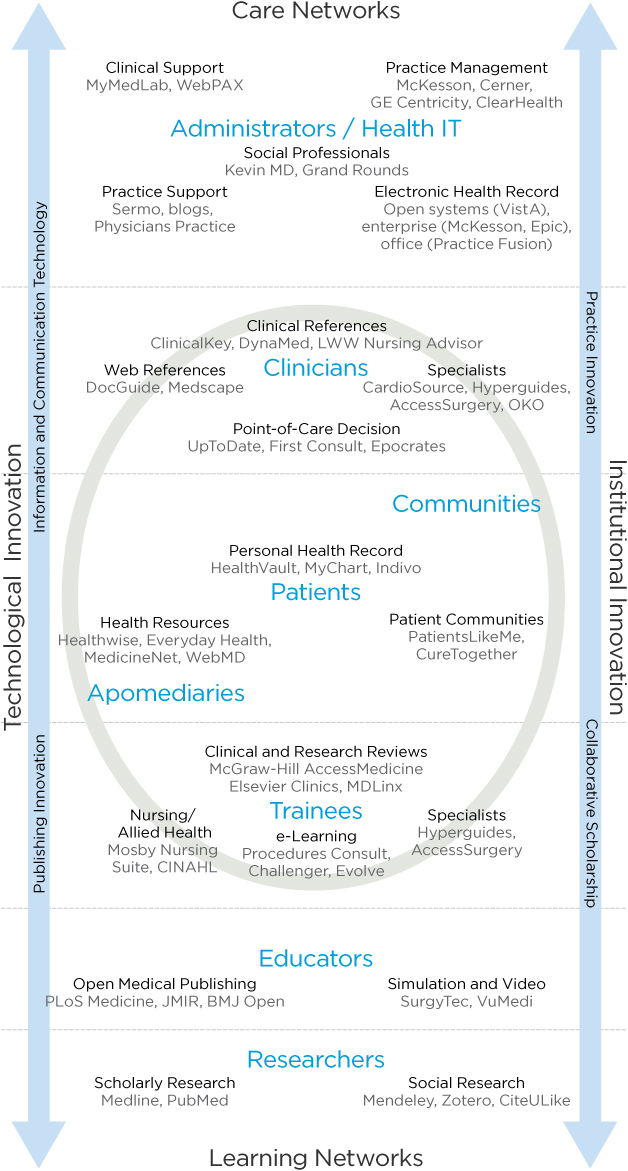

Consider the wide spectrum of healthcare practice and clinical applications in Figure 4.4, a framework that encompasses enterprise HIT, point of care decision support, practice management, patient engagement, and clinical references. A full range of clinical roles are shown, from administrators and clinicians (in care networks) to educators and researchers (learning networks), with “patients” located in the center.

The framework centers on patients (health seekers) as the purpose and intended outcome of most clinical applications. Clinicians (of all disciplines) and trainees are the professionals most closely engaged in patient care, and are included within the circle. HIT applications are aligned toward institutional applications (at right) or technological applications (at left). The exemplary services indicated are today’s current leaders in those categories.

Patient-focused decision support (on the technological side) includes tools for health information and self-care, if not diagnosis. Patient communities (on the institutional side) create social networks for interpersonal exchange and support. These communities are starting to replace the institutional function for individuals, and institutions are in early stages of creating online and local communities for their own constituencies.

Today’s patient-centric applications will inspire new forums for engagement and dialogue between the public and professionals, and the role of mediators will expand. Apomediaries are new roles for credible information brokers and participatory community managers. As identified by Gunther Eysenbach, founding editor of the Journal of Internet Medical Research, apomediaries are central to facilitating user engagement in the emerging interactive healthcare world.14 Apomediaries serve as volunteer navigators for health and disease communities, such as the active mediators on the popular Diabetes Mine health blog. This extension of the coordinator role can be seen as the leading edge of an institutional innovation yet to be capitalized on or formalized.

FIGURE 4.4

Health information technology spectrum.

Consider the impact interactive healthcare is already having in leading institutions. Mike Evans, medical director of the Health Design Lab at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, draws the comparison between changing healthcare practices and new management thinking: “If you make the analogy between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, I think the system before has been very reactive, not interested in user experience. It’s about putting out fires. And now in Health 2.0, we are seeing that we need to get out in front of these problems, we need to anticipate problems, with patients driving the bus.”15

How do we get patients to “drive the bus”? Evans’s vision of agency is one initiated by health seekers or patients themselves. It is a people-centered design movement in which human and community needs drive design, and technology is subsidiary to the values of care.

The Health 2.0 and HIT ecosystems fill hundreds of niches that reach beyond patient and professional services. However, in the evolution of patient-centered service, even purely administrative applications have to connect to patient needs at some point in the value chain.

DESIGN BEST PRACTICES

• Health is experienced individually but is managed socially. Health seekers are not isolated patients but community members. A traditional user-centered approach can overlook systemic relationships by overly focusing on a defined technology or a specific market segment.

• Design thinking is not a solution to every healthcare problem, but rather a perspective and set of guidelines for finding and framing the right problems where design practices can provide extraordinary value.

• There are a small number of universal information needs. As a starting point, design information to support the wayfinding of these needs for health seekers.

• Any design process requires trade-offs between providing a simple answer or the complexity of multiple options. Safety rules—the risk to a health seeker making the wrong choice should be the guiding principle.

• Health 2.0 is a transition phase, not to Health 3.0 but to a consolidation of information services integrated at the point of need. These will include patients, point of care, patient management, practice management, research, and education.

Case Study: St. Michael’s Health Design Lab—Health Design for Self-Care

US healthcare providers are incentivized to compete with each other for patient and physician business, a situation that warps the service landscape and demands technology and institutional innovations to maintain competitiveness. Hospitals and group practices make strategic investments in specialized equipment and systems, affiliates for diagnostic imaging, and expensive physical plant renovations. In the smaller, publicly funded Canadian system, institutional networks find innovative ways to make an impact on healthcare at the point of most leverage—not always at the point of service but at the points of citizen learning and awareness.

This design case describes one of the projects of the Health Design Lab (HDL) at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, a patient-facing innovation group managed by a joint clinical, business, and designer team.

Mike Evans, a family physician and director of the HDL, stays connected to popular culture and media as a way to improve the public impact of health communication. Evans gives talks, broadcasts as the House Doctor on CBC Radio, and writes newspaper columns to further his goal of reinventing patient education. At the HDL, he and a team of healthcare innovators have been designing new approaches to education and public engagement with health issues. Evans and the HDL have created a true transdisciplinary design team—filmmakers, designers, marketers, researchers, clinicians, technologists, and patients—to create tailored media that speaks to people today. The HDL is creating virtual “knowledge buffets” for patients to interact with and to optimize their self-care, including mobile reminders, social networks for chronic disease patients, self-selecting videos (skills, inspiration, advice) with peers and experts, and comic book–style health books for children and patients with low literacy. Evans described the HDL team as collaborative solution finders:

We are mostly patient facing. To be able to create the perfect solution, you need to be clinic facing, clinician facing, and patient facing. Our niche is definitely the patient. We have a couple of strategies within that. One is the collaboratory concept; most interdisciplinary healthcare means that a pharmacist, a nurse, and a doctor are working together. Almost all solutions in medicine are derived internally, from the people in the clinic. There is little user study and there is very little of bringing filmmakers, writers, MBAs, [and] technologists along with patients.16

For example, the HDL designed a series of colorful baseball card–style flash cards for diabetes medications. The cards reveal a seriously playful side of care design, presenting information in a way that engages patients and caregivers.

Innovation through Collaboration

In another project, the HDL joined a larger consortium, Toronto’s University Health Network, to design systemic responses to cardiac care for chronic patients—in particular the wicked problem of atrial fibrillation (AF). A signal of more serious emerging disease conditions, AF is experienced as serious when it occurs and is difficult to identify and treat in isolation. It is a symptom of a bigger problem yet, disguised as a condition, requiring treatment and expensive continuity of follow-up.

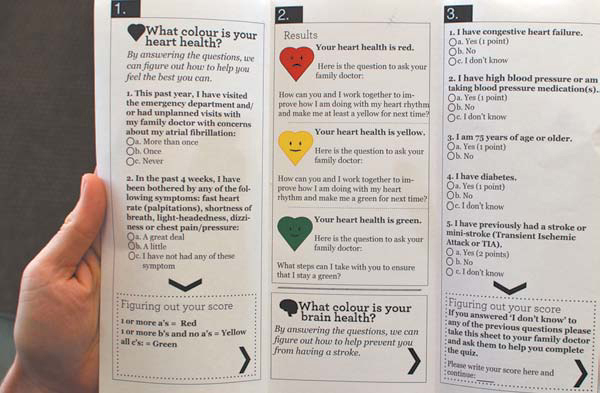

The HDL team developed a series of patient communication resources to intervene in the “front end” of AF care. Know Your Colours is an assessment tool for patients designed to capture and utilize information on unplanned care, impact of symptoms on quality of life, stroke risk, and management to improve care. Results of the quiz are then classified as “green,” “yellow,” or “red,” with specific advice provided for each (Figure 4.5). A physician-facing side of the tool provides straightforward direction to the physician. According to designer Heather McGaw, “We envision this tool as eventually becoming a stand-alone, available at multiple touchpoints (e.g., in waiting rooms and online) and through various mediums (e.g., paper, kiosk, tablet, online).”17

The tool is aimed at motivating patients to work with their healthcare team to make sure they are receiving optimal treatment to prevent stroke and manage their symptoms.

FIGURE 4.5

The Know Your Colours atrial fibrillation assessment tool (model). (Courtesy of Health Design Lab)

The HDL has adapted creative workshop processes for ideation and concept design. A cross-disciplinary brainstorming session was conducted for the patient-centered AF care problem. A team of clinicians—pharmacists, a family doctor, an emergency room physician, a nurse practitioner, and the HDL medical director—were engaged with three designers, with facilitation by clinical lead and designer McGaw.

Lori MacCallum, who is a pharmacist, assistant professor at the University of Toronto, and HDL clinical lead, produced the AF research and collaborated with McGaw on developing visually effective artifacts for the workshop and project. MacCallum’s advance fact finding included a review of the medical literature and expert interviews. The findings were then distilled into key “care gaps” in the management of AF, defined as points in the patient journey where care delivery might break down or opportunities might be missed to effectively treat the person with AF. The workshop engaged clinicians in working with three key gaps:

1. Poor initial diagnostics in the emergency room for AF symptoms

2. Lack of standard process for routing AF conditions

3. Lack of consistent AF management

Personas were developed from the background research to represent each of the sub-populations of AF, such as Johnny Fit, Mary Multiple Chronic Disease, Caring Kristy, Frail Frank, and Tom, A Guy’s Guy. One persona in particular was key to the process. Tom, A Guy’s Guy was representative of a traditional and aging segment of the population who are not online, would never be online, and might distrust outreach programs (Figure 4.6). The program and artifact were designed to meet the most difficult of persona types, with the expectation that if persona Tom’s needs could be met, the other types would be easier to meet.

The care gaps and personas provided clinical reality and structure to the brainstorming session and kept it focused on possible patient outcomes.

User segments were stuck to the wall and referred to throughout the session. The brainstorming generated roughly 100 ideas, which were reduced by group voting on concept strength and highest priority. Participants voted for their top two choices, and a consensus was reached on a starting point. The ideas were captured and displayed in a concept map and shared with participants to validate the starting point.

Based on the priorities and ideation, a self-identifying quiz was chosen as the initial HDL product for the Innovate Afib program. Various concepts were developed by the designer with content provided by the clinical team, following an iterative process of simultaneously creating and editing content while designing the information architecture. The initial version designed for patient use was defined as a paper instrument.

FIGURE 4.6

Persona for Tom, A Guy’s Guy. (Courtesy of Health Design Lab)

The HDL completed usability testing with patients in various stages of care (in-patient internal medicine, electrophysiology treatment, pain clinic treatment, and primary care). The paper version was evaluated and refined before it was designed and promoted into digital online channels (including a mobile app and online Web resource). The AF assessment tool is planned for wide use in family practices, and the HDL will continue to collect feedback and monitor its uptake.

Although baseball cards and short video documentaries may not seem like the stuff of Health 2.0, these communication tools use creative design to promote health in the larger community, simply and directly. Their lesson is to follow the needs of real people—to meet them where they live and to speak their language. This community focus does not inhibit the HDL from facilitating design for more complex, integrated healthcare issues.

Designing Healthcare Communications for All Communities

The HDL is designing tools for public use on the Web and has become far more accessible online. Evans says his patients typically see Dr. Google first and are somewhat informed when they visit his practice:

The Health Design Lab was started to redesign the patient education experience, to make it richer, more effective. Right now, we give patients pamphlets, and that is the extent of the patient education. There is a large Dr. Google effect out there, and this marks a huge paradigm shift in medicine. Ten years ago, no one did that, and today 75% to 85% of people who visit me in the clinic are visiting Dr. Google.18

The resulting cultural change is that healthcare providers are now able to reach out to patients, online communities, and the public by adopting the media channels their patients and families use. If the goal is effective health communication, the means to communicate have become easier for producers and consumers, and technologies that enable sharing and listening fade into the background as human connection takes place. In fact, Evans points to the social technology of collaborative design as the most powerful tool in the HDL’s work: “I would say our greatest achievements have come from the collaboratory, like partnering with a filmmaker to do digital storytelling. In Health 1.0, that might have been done with medical media, where a patient comes into the hospital and reads a script in a designed space.”19

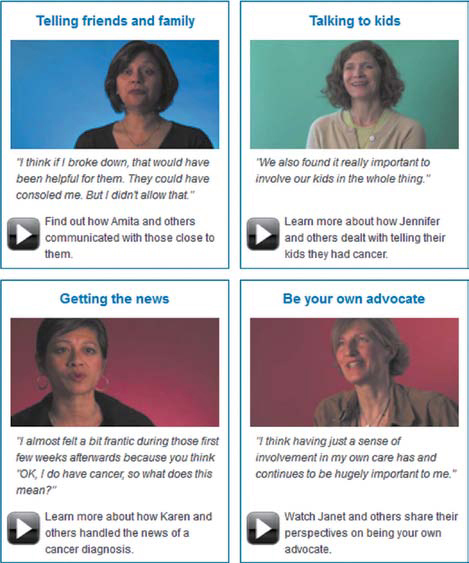

Produced as conventional media that is hosted online, the HDL designed videos to create a personal context for patient understanding and to help people communicate with family members or take action on their own health (Figure 4.7). The HDL recognizes that patient information seeking leads them to a wide range of information that is self-selected by the seekers. The more authentically compelling the media, the better the chance people will discover it and pay attention. According to Evans, “81% of people are going to the Web, but if you have chronic disease, it’s down to 62%. The people who need it the most are not accessing the resources. Follow-up research shows that if you led them to the well, showed them how to use the resources, they were heavy users.”20

FIGURE 4.7

Health Design Lab’s “Truth of It” cancer experience documentaries.

To address the problem of public users finding relevant resources, the HDL’s “Truth of It” series shows real people talking about their own cancer situations, empathically interviewed and presented with crisp, professional-quality video values. Viewers were found to identify with others with their condition, rather than a doctor or an actor, and personal relating was considered more likely to result in personal action. As more people discovered the series, the HDL expanded it, and it has become very popular. The videos have become embedded across multiple media channels (clinics, self-care sites, health websites) and in a variety of media modes (YouTube, Twitter, mobile apps), reflecting the different ways patients access information.

Although the HDL business model may seem uniquely Canadian, the “health design research” approach can be transferred to the United States and other locations in the form of regional health design networks and health design centers at the major research clinics. For example, Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation operates under a mandate of enhancing care practice, redesigning medical services, and reducing process overhead through an internal core team and a large network of supporting organizations. Like the HDL, Mayo’s focus is oriented to large community outreach. However, Mayo’s organization has a dual mandate of internal process improvement, to which the Canadian groups are not especially dedicated. The Mayo model would be inappropriate for a hospital or regional system, but the HDL business model could be a shared-support, regional design center that assists multiple inpatient and outpatient clinics without competing between them.

The HDL and St. Michael’s demonstrate that healthcare innovation can be initiated with a small group of dedicated clinical and design professionals. As their mandate has expanded, they have introduced designers from OCAD University, ethnographers and qualitative researchers from the Li Ka Shing Institute, and local design firms. As Evans explained,

Our niche is . . . prototyping. We are not looking to become a WebMD and to have all the resources on our site to manage cancer care or diabetes care. We feel our role is more [about] bringing together the collaboratories—bringing together the different skill sets, applying a design process to that, and having an initial iterative process where we prototype a resource and then hand it back to the funder.21

Healthy people seek designed experiences and artifacts to enhance their appreciation of life. People facing an illness or a caregiving context may be so immersed in the constraints of the situation that their ability to recognize the possibility for a better experience may be dramatically curtailed. The provision of better experiences begins with those who deliver help and care, because they can communicate with hundreds of patients and have the chance to influence each one in a positive way. There are many opportunities for direct providers—physicians, nurses, staff—to recognize and innovate. However, clinicians have little time and no mandate for process innovation. Innovation will continue to lag efficiency and operational values unless the costs and value to practices can be credibly established. Organizations like the HDL can help build this case for the healthcare professional community by documenting applications and successes, and showing measures of improvement in treating patients earlier, good care management, and reducing return visits.

• The opportunities for healthcare service design often arise at the level of direct care, not from top-down strategy.

• Any organization serious about community outreach will benefit from design values that better leverage their investment. Even simple print and Web communications can be vastly improved to amplify their impact.

• Design teams connected to healthcare organizations are a very new trend, and there are no perfect operational models yet. The best examples are in-house designers who learn the field from within.

• The typical digital agency model is not recommended for care design because of the significant requirement to understand actual patient care and community needs.

• A vernacular design approach that communicates in plain words and simple visual communication may best reach patients and health seekers where they live and work.

• From a social perspective, underserved patients need more assistance than the well served and computer literate. A real design challenge is found in communicating simply across social and language barriers.

Methods: Tools for Agency

Three design and social research methods (among many) offer design tools for agency, practices that enable design researchers to elicit personal meaning from the perspective of the health seeker. Empathic methods aim to understand experience from a person’s point of view and to relate the experience faithfully. Agentic methods dig deeply into a person’s expression of meaning, their causes and passions, and may help them achieve or communicate large goals. Although these are not tools or methods for direct agency to effect change, they help researchers make an advocacy case for the agents of their studies. These approaches are inspired by social critic Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality, which advocated enabling people with “tools that guarantee their right to work with independent efficiency.”22 Video ethnography, design documentaries, and Dervin’s Sense-Making Methodology return the primacy of communication to the person. While the designer organizes these methods on behalf of a project, the goal (at least directly) is not merely to optimize the system or service in which the person participates. These tools present a person’s experience as closely as possible to the concerns in his or her worldview.

•Ethnographic field observation and contextual interviews are the fundamental basis for the following methods. Ethnography in clinical and patient settings has been covered deeply in the literature, ranging from design ethnography for patients to professional practice ethnography (including medical practice, education, and HIT).23

•Video ethnography allows the researcher to capture real-life activity with on-site interviews and recordings of everyday consumer behaviors.24 This method allows the design and client team to construct interpretations with community participants beyond the typical recording of on-site observations.

•Design documentaries allow designers to create empathetic presentations of complex information scenarios as video storytelling. They are a powerful tool for attracting and educating the public about health and disease management, and they can educate and inspire large organizations to communicate compelling narratives to inspire action.

•Dervin’s Sense-Making Methodology (SMM) is a deeply researched social sciences method for understanding human experience in learning, self-informing, and understanding another’s lifeworld experience. SMM is unique in experience research because its research base supports both a methodology (the framework and philosophy) and a series of techniques for its implementation in the field.

Ethnographic Observation

Ethnography can be considered the basis for the following methods, and readers unfamiliar with ethnographic research methods might start with fundamental works25 and apprenticing with experienced ethnographers. Skills in field research and observation must be developed with experience, and the clinical setting is no place to experiment. As a social science research method, ethnography investigates social behavior and human culture within specific settings. The traditional methods of cultural anthropology require the ethnographer to observe a culture for sufficient time to learn the norms and values of the people in that setting. For professional practice settings, or for practical design applications such as new service or IT design, more rapid and applied forms of ethnographic research have been validated.26 Data collection is based on qualitative research practices—interviews, note taking, video, and photography. Ethnographic data is analyzed by open-ended discovery of patterns within discourses, and by mapping data to internal categories of theoretical interest to the study.

Ethnographies are often initiated by a series of observations in the setting using a framework such as POEMS, developed by Institute of Design professors Vijay Kumar and Patrick Whitney,27 or the e-Lab’s AEOUT, two well-known observation frames that guide the investigator toward meaningful and structured observations:

• POEMS (People, Objects, Environments, Messages, Services): This framework also serves as video observation tagging categories for video ethnography.

• AEOUT (Activity, Environment, Object, User, Time): The e-Lab framework provides a basis for journal recording of observations over extended periods. Entries can be categorized and mapped to any of the major category labels.

These frameworks are advance guidelines to orient observation in workplace settings, where long observation stints are often out of the question.

Video Ethnography

Video ethnography is often employed as an empathic method, lending immediacy and vivid narrative to healthcare product design by presenting the stories of real health seekers. Although video can be recorded in any situation deemed helpful for design, optimal applications involve situations where behaviors are hidden to product or clinical team members:

• A patient’s experience at home, where clinicians have no access

• The experience of a person remembering and taking medications at home or work

• The experience of a diabetic managing tests and insulin kits

• The experience of a consumer in a store or clinic making choices among options, such as over-the-counter medications

Video allows a single ethnographer to document situations of use that capture the reality of everyday health concerns. Danish professor Jacob Buur’s examples in Designing with Video show video employed as a tool for documenting experiences inaccessible to other means of research.28 Jason Moore of Xinsight carried out a video documentary with Buur for Novo Nordisk, a Danish healthcare firm with a core business in diabetes care products. Moore reported how he was able to capture the private experiences of diabetics and share this human realism with a development team responsible for injection device design:

As we were entering people’s private lives, we decided to work through video recordings rather than bring people in direct collaboration with the design team. . . . The participants were mainly mechanical engineers who work with designing needles and injection devices. . . . The goal initially was to get to know the people in the video, and later to identify design opportunities and envision new products.29

Moore points out that video in itself is not sufficient. Client observers must be sensitized to understand the meaning of interactions and statements to their design decisions. A video card game was used to engage the design team in collaborating around the meaning and opportunities represented by the video experiences. Using index cards to record their own interpretations about segments of the observed video, the engineers, marketers, and other client team members contributed their ideas and concerns about the use of their products in these scenarios. This led to a more substantive anchoring of the video research than merely presenting and discussing the findings from the video ethnographer’s perspective.

They noted several ways in which video ethnography informs design:

• It bridges the gap between people and patients and the designers.

• It enables designers to reconsider their view of “problems” and “solutions.”

• It gives designers real-life support for design decisions.

• It provides a way to develop an ongoing story in the design process.

• It provides a clear artifact documenting the situation and its motives and relationship to the organization.

Design Documentaries

Data collected through traditional means are often dry, impersonal, uninspiring, and/or lacking context. Design documentaries are the manipulation of compiled research data, including text, video, audio, photographs, and illustrations, into a short-form video format used to inspire dialogue, locate possibilities for exploration, and further guide the design research process.30 Their audience and use differentiate them from documentary films.

This method is useful for a discovery phase, research review, problem assessment, and early prototyping, and to instigate a deeper dive. The resulting production of design documentaries can be used as true-to-life personas and as public presentations of consumer and patient responses to new services, health practice changes, and so on.

Design documentaries were originally developed as a design research experiment by design anthropologist Bas Raijmakers,31 but they were found useful as a method to help design teams:

• View their subjects as people, not just as customers (or patients).

• Better envision how their designs would impact people.

• Understand their emotional attachments to the people for whom they are designing.

• Obtain more information and details on a person’s environment and on how certain events really play out in everyday life.

Design documentaries are best used when research material requires an emotional bridge between the subject and the designer. Although beneficial when presenting or reviewing research results with the design team, filmmaking preproduction considerations can help plan or strategize a user research design. (For examples, see www.designdocumentaries.com.)

Dervin’s Sense-Making Methodology

Dervin’s SMM comprises a meta-theory, methodology, and a series of research techniques developed by Brenda Dervin over a 30-year period of scholarly work and research development.32 SMM affords design researchers a rigorous and descriptive method for interviewing and discerning experience patterns, while also mapping to a theoretical framework that guides analysis of participant data and assessment of its meaning.

Used correctly, the methodology provides a rich source of qualitative, experiential data. It leads to compelling understanding of the reality of human experience with technology and services, and the understanding of information behavior. SMM expands our capacity to reach deep insights from studying these experiences:

• Information seeking

• Online experiences

• The experience of learning and being a learner

• Living with difficult health situations

• Being a member of an organization or other social group

• Being a consumer of complicated services such as healthcare

Among the several schools of sensemaking theory and research, the SMM process is interpreted differently, even for similar problems. These approaches investigate how people pursue goals and make sense of events, develop mental models, and interpret data in problem solving, and how people in organizations form a collective understanding of situations.

Dervin’s SMM is the only approach that integrates a method of experiential inquiry—an interview and analysis method that provides a research framework for addressing questions of the individual’s encounter with resources and information in his or her negotiation of everyday complexity:

• What is the reality of people’s experiences with information or systems?

• How do we interview people to understand their experience?

• How do we make critical assessments about how people make sense of and communicate their experience?

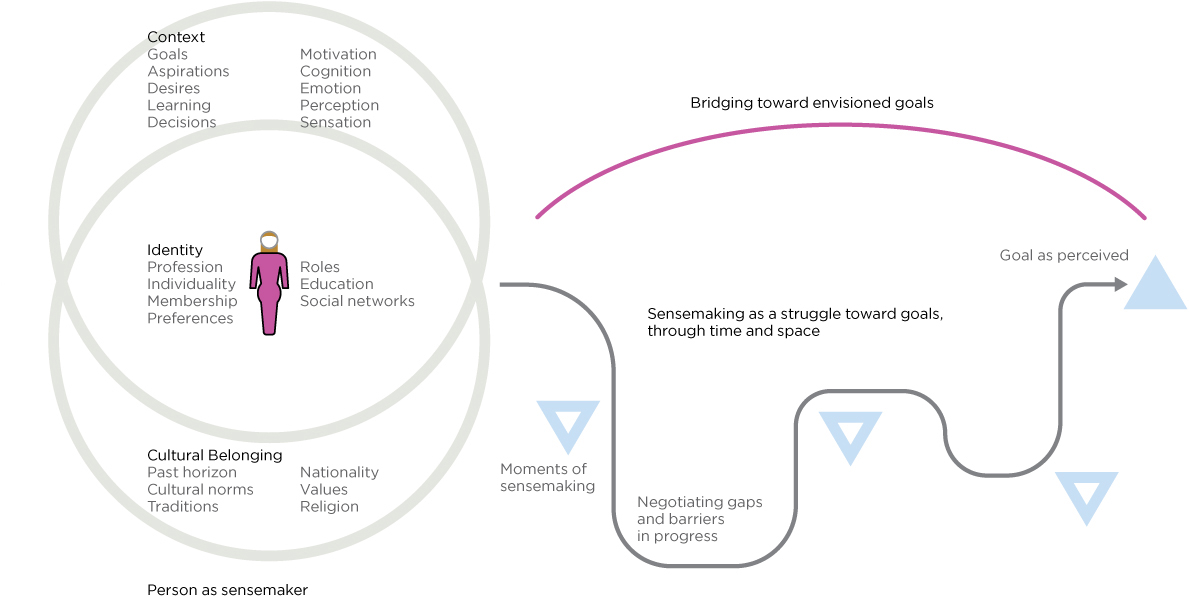

Figure 4.8 illustrates the experiential journey of a health seeker toward an intended outcome, adapted to Dervin’s theory of user sensemaking. The unit of experience is the situation, represented by the person in her context (bubbles) and her situational starting point (represented by her position at the left, moving through life toward goals on the right). At all times she is experiencing a range of thoughts, emotions, anticipations, expectancies, urgings, and considerations. People are intentional, goal-driven actors, and Dervin’s method recognizes that human experience is always in motion, and that sense is made through “verbings,” or actions in the world, not by identifying information or goals as passive objects (nouns).

In line with the notion of verbing, the figure represents a person navigating the obstacles, gaps, and “muddling through” in interactions with things and resources and in pursuit of goals or outcomes. The outcome (on the right) may be one of many concurrent goals undertaken, as is typical in health seeking. Dervin’s SMM examines every aspect of this journey.

Dervin describes the methodology as a way of inquiring into the authentic experience of informants from their perspective, in their own words, and related to their own purposes:

The point is that Sense-Making aims to arrive at a useful understanding of human sense-making to be used in the design of information and communication systems and procedures. In method, then, Sense-Making asks actors if they bridged gaps and how. The how is not constrained: actors are explicitly asked what emotions they felt, what feelings they had, what ideas or conclusions they came to; and actors are asked how each of these helped and/or hindered.33

The neutral questioning or sensemaking interview is an empathic interview method that generates rich data for understanding individual goal-seeking, service experience, or information behavior.34 The neutral interview is empathic in the sense that, with open and nondetermined questions, the participant is free to respond with his or her own narrative and personal context and is not constrained by the typical demands of a product-centric interview. Even in user experience, researchers typically establish a strong focus on use of interfaces or products, as opposed to genuine experience in the hermeneutic sense of personal meaning. This apparently simple set of questions probes the understanding of how an individual really thinks and responds to situations. Used correctly, it lends structure for a rigorous inquiry into the actual experience of a person in a situation.

FIGURE 4.8

Sensemaking in the health-seeking context.

The interview process was designed as a neutral and general instrument, originally for librarians to interview participants (and patrons) about their information needs without biasing their responses in any way toward certain resources. These neutral questions are associated with three fields of experience of the user or participant: (1) the situation, (2) the gaps in experience, and (3) uses and helps for user intentions:

UNDERSTAND THE SITUATION

- What brought you to this point?

- What happened that stopped you?

- What are you working on?

- Where would you like to begin?

- What aspect of this situation concerns you?

UNDERSTAND THE GAP

- What seems to be missing for you in this situation?

- What do you need that you do not have available?

- What brought you to this point? What are you trying to understand?

- What are you struggling with? How is this typical, or not?

WAYS OF SEEKING HELP

- What services or tools are available?

- What would help you?

- What are you trying to do?

- Where do you see yourself going?

- If this could turn out any way, how would you want it?

- How do you plan to use it?

• Situating agency is not just a social sciences approach to user research. As design researchers, we are responsible for presenting a person’s life and choices in the context of their own experience and goals.

• In all contexts, method selection is critical to the research goals. Direct, in-depth, face-to-face interviews with patients help us to understand health seeking. Interviewing is the baseline method upon which others are combined.

• Video recording of (patient) health-seeking situations is not advised as a standard method. It applies when an ethnographer can gain access to real-world insights unavailable by other means. In a patient context, video recording can be experienced as intrusive and the data must be very carefully handled. Video data is typically viewed and interpreted at a later point, making it subject to meaning loss.

• Video interview methods must be reviewed for ethical concerns, presented to participants using informed consent, and the files protected by the researcher to ensure privacy agreements are met.

• A sensemaking interview approach can be integrated with formal evaluations or interactive usability sessions; however, the intentional sequence of questions should be maintained as a whole inquiry process and not intermixed at the question level.