CHAPTER 2

Co-creating Care

Elena’s Story: The Family Caregiver

Elena Reiser is the primary caregiver in her household. She takes care of her ailing father, Ben, and is an active mother of a preteen girl, Andrea. She spends nearly an hour overall in an average day seeking health-related information for her father, her daughter, or herself.

Late last year, Ben experienced congestive heart failure, a severe attack that imposed the requirement to downshift his lifestyle, take several pills a day, and watch his diet. Ben was out of shape after two decades as an active executive who worked long days and ignored increasing signs and symptoms of physical difficulty. After a golf outing with friends, he experienced angina chest pains and extreme shortness of breath. Widowed and living alone, his first thought was to call his daughter, Elena, not an ambulance or other emergency assistance. She has been helping manage his care ever since.

Today Elena searches for authoritative materials to inform herself about her father’s recent cancer diagnosis. She hopes to find trustworthy articles and posts from other people dealing with cancer in their families. Ben faces colectomy surgery to remove and resect a cancerous section of the lower bowel discovered after a fortuitous colonoscopy. Less than a week ago, a gastroenterologist removed and biopsied polyps discovered in the examination and determined their malignancy in on-site tests at the outpatient surgical center. The physician immediately scheduled a surgical intervention.

Ben is scheduled for additional imaging and tests prior to the surgery, and Elena’s contact list of clinicians will soon grow to five different providers necessary for her father’s care—a private family physician, a practicing oncologist, a gastrointestinal specialist (a senior resident), a general surgeon, and a nurse practitioner—not to mention the anesthesiologist, pharmacists, visiting residents, and shift nurses.

Ben’s surgery is another major health situation in the family, coming 4 years after Elena’s mother succumbed to lung cancer, and bearing the responsibility for her father’s care is taking a toll. Caught between the emotional concern for her father and the complex medical system she navigates on his behalf, Elena has become a primary care manager. She spends time on the phone seeking advice, manages appointments and travel, helps Ben manage his complicated medication schedules, and scans materials online.

Busy taking care of others and keeping up with her full-time job, Elena is continually stressed, and she is neglecting to take care of herself. She has stopped exercising regularly, and fast food meals have become common as her daughter’s schedule and her father’s medical needs crowd her time. Elena has found it necessary to postpone nearly all other priorities while taking care of her father. Keenly feeling the possibility of losing both parents to cancer within a short time, she has taken great pains to learn about the situation and negotiate the healthcare process as her father’s caregiver.![]()

Infocare

Man finds . . . his place by finding appropriate others that need his care and that he needs to care for. Through caring and being cared for man experiences himself as part of nature; we are closest to a person or an idea when we help it grow.

—Milton Mayeroff, On Caring1

As the largest demographic cohort in history ages and calls for special care, Elena’s situation will be increasingly common. Therefore we are all stakeholders in personal, institutional, and community healthcare. Will the next generation of health services be sufficient to handle this historical shift? How might we better design the way care is delivered and experienced?

People have always sought to learn more about a health condition they or a family member are experiencing. In the past, information and advice were sought from doctors and other people experiencing the condition. The Internet has enabled global access to a massive amount of basic health knowledge, creating a vast database of published work and an accessible ecology of information resources associated with disease conditions, therapies and treatment, personal experiences, and research.

In less than a decade, an extraordinary shift has occurred in the information behaviors taken by individuals seeking to learn about and improve their health. Instances of health information seeking, as with the health concerns they reflect, are associated with a person’s experience of ill health. The health seeker is a person acting on the intention to pursue or sustain health, and health seeking is a purposeful activity that aims to restore or improve health. This new, neutral term gives context to the full range of experiences a person encounters in the pursuit of a homeostatic balance of relative good health.

Designers who build resources to help educate, inform, and enable individuals to make effective health decisions might start by understanding the situations of health seekers and their cognitive and affective participation in their own journeys to health.

People often do not consider their health until it is threatened by an incident or concern. Then their health-seeking journey begins by recognition of a knowledge gap, or need for further understanding, a health information need. A practical view of information needs comes from clinical practice researcher Paula Ormandy, who defined health information needs from a patient’s perspective as “the recognition that their knowledge is inadequate to satisfy a goal, within the context/situation that they find themselves at a specific point in time.”2

People in reasonably good health are not typically online every day seeking health information, and are generally unconcerned with the crush of resources available to inform decision making. People with chronic conditions (such as pain, diabetes, or cancer recovery) may seek a more or less continuous flow of information to help with their everyday concerns.

When any concern arises—whether it’s sleeplessness, an unusual internal pain, or a chronic condition—our perspective changes, our information activity becomes focused and intentional, and in some cases our identity changes. A personal mood shifts from the indifference of everyday health to that of relieving a concern. Health seeking begins in earnest. People may undergo a significant change in identity—from a nonmedicalized self to that of a patient or even of a disease sufferer.

Consider the patient’s entire circle of care when designing for a patient context. The circle of care includes not only immediate family and increasingly responsive providers but also extended family and friends as direct caregivers. Patient-centered philosophy recognizes that serious illness touches everyone in the health seeker’s life. The notion of a disease “survivor” or “living with” a disease has expanded from patients to their entire circle. Everyone is caring, cared for, and a “survivor.” According to Peter Pennefather, research director of the University of Toronto’s Laboratory for Collaborative Diagnostics, “the term ‘cancer survivor’ has evolved from ‘patients who survive treatment for more than 5 years’ to ‘persons diagnosed with cancer and their relatives, friends, and caregivers.’ A similar shift in emphasis from curing a disease one person at a time to collaborative coping with general symptoms has occurred with other chronic diseases.”3

How do we co-create care across these separate domains? We have few guidelines to help us design services for distributed care because most of us have lived our entire lives under a doctor-patient model of care. Care support and medical decisions are typically shared between patients and their immediate caregivers. In the “consumer” health context, where the design team has no contact with dedicated or frequent users, it is increasingly important to give caregivers centrality when making product design decisions. Although the goal of a consumer health site or product may be to inform or support the “patient,” there may well be multiple health seekers involved in any given episode.

Health Information Design Is Personal

Healthcare design draws extensively on knowledge and methods from the human and social research fields, more so than other vertical design domains (such as finance, retail, or entertainment). A broader literature base is necessary when attempting to describe and design across the complex functions of body system, clinical service, and community health. When designing for other complex services in other fields, design research representations (personas, customer journeys, user models) can often be general and sanitized with little loss of fidelity. But in health scenarios, these narratives become personalized. If we generalize, we risk underestimating the complexity and emotional issues involved in the actual situations being addressed.

The risks are higher when lives are on the line. When we recognize that a persona could be a relative and a scenario might occur in our own family, our tools become less abstract.

Health Information Needs

Information needs are a presumed cognitive state wherein an individual’s goal state triggers information seeking in a given context. The concept of information need helps understand user motivation and provides a lens with which to view behaviors that focus on motive, goals, and activities.

Information scientist Robert Taylor originated the concept in a 1962 article, “The Process of Asking Questions,” which describes four types of needs:

• The actual but unexpressed need for information (visceral need)

• The conscious, within-brain description of the need (conscious need)

• The formal statement of the question (formalized need)

• The question as presented to an information system (compromised need)4

Taylor’s four information needs have been cited continuously for 50 years and have acquired validity due to influence perhaps more than science. They were defined long before cognitive psychologists researched human information interaction. For our purposes in the consumer health sector, we can say individuals seek information to inform the many issues that arise in the context of a health situation.

Care professionals are increasingly interested in the health-information-seeking behavior of patients because these patterns reveal the patients’ interests, of which healthcare practitioners should be aware. What information is involved in health seeking? Oxford researcher Angela Coulter’s research5 identifies 12 recurring needs and aims that hold true whether people obtain information from professionals or libraries or the hundreds of health sites that have emerged on the Web. These 12 motivators for health information seeking define a sequential series of information needs relevant to the patient experience life cycle:

- Understand what is wrong.

- Gain a realistic idea of prognosis.

- Make the most of consultations.

- Understand the processes and likely outcomes of possible tests and treatments.

- Assist in self-care.

- Learn about available services and sources of help.

- Provide reassurance and help to cope.

- Help others understand.

- Legitimize seeking help and their concerns.

- Learn how to prevent further illness.

- Identify further information and self-help groups.

- Identify the best healthcare providers.

Information seeking is often expressed in terms of a need and is defined in relation to need satisfaction. Health seekers are attempting to achieve personal health goals; they make sense of emerging situations and have critical decisions to make. Elena’s scenario introduces new information needs in every chapter. Her father is facing multiple, interconnected medical, health, and life choice situations with his impending cancer surgery. Elena, as his caregiver, is motivated to understand her father’s disease condition, medical treatment details and options, and post-treatment care.

Making Sense of Health Information

Information seeking can be a messy process in reality. Searches and sources lead a seeker to unexpected resources, information “places,” and objects that draw attention and bias or bend the journey to different perspectives. How is a searcher to vet the validity of a government site (such as CDC.gov) versus an advertising-sponsored site (WebMD) or an independent activist information site (ThinkTwice.com)? Information seeking is value-laden. Objective representations of a site’s credibility are not sufficient—health seekers are emotionally guided and may not embrace a scientifically informed view of evidence or facts.

Designers must learn to recognize the power of confirmation biases in information seeking and health issues. Confirmation biases, hundreds of which have been identified, are cognitive frames—essentially beliefs about a situation—that orient seekers toward locating and confirming opinions from sources that agree with their expectations. Often, these biases are rooted in a context of hope or the expectation of a positive outcome. Others seek clues and support for a negative concern. Hypochondriacs, for example, seek confirmation for negative health outcomes, such as every facial mole having the likelihood of being a melanoma.

Outcomes of information seeking can be thought of as information objects. In search activity, these are often discrete texts or pictorial representations that may be separated from their original context. The separation of objects from context renders them the equivalent of discrete factoids that present actionable information to some readers. We might recognize that consumers may not stray far into the details of the digital health domain, and they may attempt to supply meaningful contexts (domain URL, authority citations, brand) to health information at the page, article, and paragraph level.

Encounters with information are informing and multidirectional. That is, a health seeker engages in sensemaking—actively pursuing resources that contribute to learning and building knowledge—to help in reaching certain goals in response to the disruptive and consequential situations of a health issue. Sensemaking describes the cognitive and affective processes by which people navigate and repair breakdowns and ambiguous situations, relying on recognizable cues and acting on patterns that fit into current or changing mental models. People encounter information not as a goal, but as an aid to making sense of their situations by adapting behaviors to new learning.

Designers structure information as content, as factual data that can be optimally presented for effective visual appeal and readability. Consider treating information not as static data (as a stock) but rather as a series of encounters in a flow toward health goals. Information has a fluid quality, as it conforms to the biases of perception. People construct information in constant interaction with their needs, contexts, experience, and background. Information can be treated as informing, a verb and activity rather than an object. While Elena is seeking answers for her father’s condition, she may find stories that appeal to her various contexts in life. Her personal (and unexamined) motives for informing will also emerge in the context of resolving an issue about her father’s cancer treatment. These encounters help people make sense of their world as they choose materials that support a perspective and help them repair the many gaps between their worldview (or mental model) and the world as presented in the informing process.

From a practical perspective, the convention of information need is assumed with a consumer scenario. For a consumer, health-related information needs are not substantially different from shopping or news information needs. People optimize their available time by conducting a limited number of searches using minimal effort (using the fewest search terms) to locate sufficient responses. In the trade-off between time and information value or quality, observations show that people maximize the utility of efficiency, or time value. Quality of information remains difficult to evaluate in any context, and the demands of time pressure create value relativity.

Regardless of whether the searcher is a consumer or a doctor, cues that indicate authority or trust are used as shorthand to navigate answer sets and articles. Consumers may evaluate quality based on a trusted institution (Mayo Clinic), whereas physicians may assess quality based on recognition of a top-ranked journal (New England Journal of Medicine) or a clinical brand (UptoDate) with which they have extensive experience. In these different contexts, the impact of brand as a recognized entity aids the assessment of expected value in information decisions. The market value of brand in health decisions is found in optimizing time during information seeking.

From a patient perspective, the value of information may relate to one’s personal condition or self-diagnosis (or any of Coulter’s information needs). Consumer and patient contexts differ because these are states of identification with a disease or concern. Information design can be sensitive to all stakeholders, not just those assumed to be users. In designing a consumer or public website, we cannot assume visitors are patients or, more superficially, information consumers or buyers. If we consider the designed outcomes as enabling health seeking, all types of activities and needs can be supported.

Health Search Behavior

How might we characterize the consumer’s health-seeking needs for information and product design? Personas and scenarios can be misleading because they only present a synthesis of the design team’s current knowledge and research (at best). How do we discover what we don’t know or have access to knowing?

There are ways to exhaustively examine the information tasks and health activities that we might have missed in first-pass or limited-access research. Among them are literature reviews, which are recommended for producing well-grounded classifications of tasks and information uses such as Coulter’s. Taking into account the information needs presumed for Elena in this scenario, we can include the following:

• To better understand her father’s condition

• To identify risks in treatment and care

• To learn how to care for her father’s condition at home

• To be prepared to converse with care professionals

And although these needs may be presumed important to disclose at a “persona” level of description, in reality each person’s situation is different and a situated context will not be so readily described. Whereas a consumer’s search for the best deal on a laptop computer might be easily defined, health situations are unique, changing, and can be complex.

Although the definition of consumer may be inappropriate in this context, it helps in describing Elena’s scenario. Adopting a consumer frame helps map design practices from consumer online services to the other healthcare sectors. It illustrates the changes in role and identity that occur when a person moves from a “nonpatient” state to the institutional definition of patient.

Elena’s information seeking starts with simple term searches and scanning the results. Based on an information use model I developed,6 a sequence of information tasks includes the six shown in Table 2.1.

TABLE 2.1 INFORMATION-SEEKING TASKS

Information tasks |

Activity outcome |

Information object |

Simple search terms entered in Google |

Scanning to find |

Search terms (1 or 2) |

Skimming search results for candidate articles |

Scanning to select |

Search results page |

Selecting salient titles |

Scanning to inform |

Online articles (less than one printed page each) |

Printing key articles |

Selecting and printing |

Printed article set (for father or doctor) |

Reading and annotating articles |

Comprehending for learning |

Printed article |

Sharing printed or PDF articles |

Exchanging meaning with others |

Printed, linked, or e-mailed artifact |

In simple searches, terms matching disease conditions return high-ranking results from Mayo Clinic, WebMD, MedicineNet, and dozens of disease-specific sites. People searching for critical health information often require the output of a simple printable factsheet. But websites are formatted for online browsing, and printable articles require time to find.

The best resources anticipate these needs and offer a range of media formats. The National Cancer Institute provides online pamphlets in both printable sections and as full PDF articles. Major institutions require registration to retrieve printable articles, which discourages rapid access or noncommittal use, because competing articles can be located within seconds from the same search results.

The majority of these resources have not been designed for the most effective use by consumers or patients. They are simply not designed as services. But many of their users may not especially care because health information needs are immediate and compelling responses to inform urgent concerns. With the vast majority of all health information seeking being initiated by a search, most of these resources display to their visitors as landing pages, indexed and linked to a search results page. Site-level navigation, site-promoted related content, and advertising become superfluous to users as ever more users reach pages directly through searches. These intrasite navigation and content features can actually interfere with information use and can be counterproductive to use if not designed with deep site page access in mind. This issue is described in more detail in the case study that follows.

From a design perspective, institutional healthcare may be one of the last frontiers (along with education and government) to accept the necessity of visual aesthetics and typographic layout. Reportedly, a recent increase in hiring UX designers has occurred across healthcare information services, as evidenced by job notices from healthcare information/IT providers. This trend promises to improve interaction, visual design integration, and information usability. Yet the industry has to overcome its blindness to good design. To encourage that trend, designers need the explicit support of physicians and administrators in healthcare services.

DESIGN BEST PRACTICES

• Better design for information seeking requires new ways to think about constituents. The health seeker is proposed as the individual actively seeking to recover his or her health or to help care for a loved one. This orientation motivates health information behavior.

• When identifying information needs, treat them as provisional (temporary and dynamic) and even speculative. We can never really know why a person is seeking information unless we understand their context through observation and feedback.

• By treating healthcare information as a dynamic flow rather than as static objects, designers can formulate more communicative and contextual resources that dynamically update information, build on social interaction, and build narratives from finer-grained information objects.

• Health-information-seeking needs should be treated as starting points, not end points. Designers should always ask “So what?” and “What’s next?” to any defined information “need.”

Case Study: WebMD—Health Information Experience

Consumer websites typically have similar presentations of the most basic background information on their landing pages, requiring diligent internal site navigation to locate advice or topics of specific value to a user. In this case study, WebMD—the most popular consumer-oriented health site—is critiqued to examine contextual usability issues as well as perspectives, biases, and design concerns from a health-seeking perspective. WebMD was selected because of its high profile with the public and its professionally developed content. This critical review is transferable to other health sites.

WebMD presents a full spectrum of health portals covering a range of interests and levels of depth. The different segments its products serve represent the most critical stakeholders in the health marketplace. Each portal presents a slightly different design and brand, but a strong family resemblance is apparent in brand prominence, color, navigation, and information architecture. Bringing together a range of consumer and professional resources, WebMD leverages a single organization’s knowledge, reach, design and development, medical advisory team, and content management. The WebMD family has consolidated five major portals (and includes at least three others not listed):

• WebMD: a general-purpose, consumer-facing Web portal

• MedicineNet: clinical information translated for consumer use

• Medscape: the most popular general medical professional website in use by US physicians in 2011

• eMedicine: a higher-end professional website cited by more specialists (now part of Medscape)

• TheHeart.org: specialist portal for cardiovascular health and cardiologists

WebMD is a platform-level innovator, a first-mover service that captured a consumer niche early and extended its position by building out a spectrum of services on an extensible content platform. Its second leading innovation among healthcare information portals was to define and structure an information marketplace using a graduated presentation of health activity. No other service provider has developed and maintains a unique resource for each of the following:

• Consumer health information seeker (WebMD)

• Health seeker with specific health information needs (MedicineNet, eMedicineHealth)

• Immediate consumer or family health queries (MedicineNet, eMedicineHealth)

• Drug information for consumers (RxList)

• General medicine website (Medscape)

• Specialty portals for specialized, evidence-based information (eMedicine)

• Specialty portals for professional topical currency (TheHeart.org)

• Personal health record (WebMD Health Manager)

A typical Web search results in a top-ranked link landing a health seeker on a view such as the one shown in Figure 2.1. Within this page of heart disease–related information, multiple levels of navigation are presented, and the user may not know which link, button, or tab to execute to advance to the next logical step. Although the decision-aid tabs may seem logical to younger, Web-literate readers, older and infrequent users may feel lost when too many options are presented.

The navigation column presents three blocks of content links related to heart disease in general. Nearly all of these are of the “See More” type and are not hierarchical subtopics or facets of the immediate subject searched (Arrhythmia). The next steps are not clear. The first navigation block presents different content types by “type label” but with no semantic information relevant to types of arrhythmia or medical actions. The second block presents a “Heart Disease Guide,” which would apparently remove the user from the current context and present an entirely different set of features. The third block, “Related to Heart Disease,” presents several links relevant to arrhythmia, but mixed in a flat list, not in an ordered information hierarchy.

Accessibility would be a problem with such a page. A screen reader for a visually impaired user might be forced to scan and read each line before reaching the main content, including any duplicated navigation.

Although arrhythmia may be a common symptom of heart disease, the presentation of the topic as part of the Heart Disease Guide joins these two together. The reader may not be able to separate the two descriptions at a later time, and may form a mental model that arrhythmia is “heart disease,” a catchall term that may frighten the person with mild arrhythmias.

The information of most value to a patient, or health seeker, is a clear description. On WebMD, competition for content placement has created a dense panoply of text and links. The excess of design sophistication will lose many users due to its complexity, and the actual user’s experience may be precisely the opposite of what was intended by the design. Health seekers oriented to one or more of the 12 information needs discussed earlier will find their experience fragmented.

If a user is in a hurry to learn about a heart condition from the industry’s leading resource, what information behaviors might we expect from his or her health-seeking activity? Consider the following five sections of the page highlighted in Figure 2.1 as a wireframe model:

A. The global navigation shows eight functional groups (most of which are compound, making this a lengthy scan). But where are we located in the site? The current context is not indicated by highlighting the label.

B. The navigation trail at left enables contextual site navigation. The topic searched (Arrhythmia) shows the top set of content links, none of which are highlighted to current context. The list requires the user to observe and negotiate between types of content (video, slideshows) and features (health tools, news archive). The Heart Disease Guide might be helpful, but is placed between the topic navigation and a list “Related to Heart Disease.” There are too many choices.

C. Content that may be related to the topic is highlighted in the right column, but until the reader understands the implications of the destination topic (Arrhythmia), these may only be distractions.

D. An advertisement totally unrelated to the topic is the most visually dramatic object on the page. The ad is echoed by a small mirrored segment below the left navigation, eliminating any white space from the crowded layout.

E. Finally, the content of supposed interest, the Arrhythmia Directory, is squeezed into the remaining area constrained by these features and links. The only relevant content is a single definitional paragraph, with sections titled Medical Reference and Features below it. In summary, the health seeker is compelled to read many of the text links before being able to make a decision about the next step to take in following the search.

This example illustrates an integrated analysis and critique for a single page of a given resource. Nearly the entire service can be evaluated based on a single page—the navigation, brand, coherence, page layout, information architecture, messaging, aesthetics, and nearly every other heuristic. In a thorough experience critique, a sample of pages and interactions within the service would be selected by consensus for review (see “Experience Critique” on page 48). The heuristic process tends to cover most of the evaluation indicators and elements in the first page selected, with other pages chosen and described to ensure completeness, consistency, and additional details not discoverable on the homepage and an example content page. The deliverable for this process is typically a consolidated report presenting the findings of all reviewers, merging duplicative findings, ranking findings by priority and impact score, and concluding with recommendations and discussion.

Consumer Use Models

Web information design for consumers may be ignoring the lessons learned from research in human interaction with print content. As sponsored or ad-supported health websites become more popular (due to their ability to buy placement and to purchase superior content), the total experience will suffer as users require more time, attention, and recovery from false starts in the dense, attention-demanding online experience. This may be the trade-off necessary to provide credible information to the health seeker, yet the possibility for ineffective communication is heightened by this complexity.

In contrast to the WebMD experience, professional medical information resources usually lack advertisements and present technical details in compact and concise encoded formats. Information providers of subscriber resources understand that physicians have no time or patience for distraction in their search for information to aid clinical decision making. The easy revenue generation of commercial advertisement has been shifted to an institutional sponsorship or personal subscription model.

Is it worth paying for the preservation of a physician’s time and attention? Should there be an equivalent public resource with simple, clear presentation of health information for health seekers as an alternative to ad-revenue-driven commercial sites? Although numerous specialist sites exist for different disease conditions and health concerns, one site in the public sector clearly meets these criteria and yet does not display in the top results of most health term searches.

Health.gov is the US Department of Health and Human Services’ public resource for information seeking about most supported health contexts (Figure 2.2). Because the site is a portal, indexed to link to partner organizational sites, and most of its content is referenced to other domains, it fails to display in open Web searches. Yet the undeniable simplicity and quiet authority of the resource shows a meaningful contrast in brand identity, communicative style, and intent compared with WebMD.

FIGURE 2.2

The Health.gov information portal.

• Start by empathizing with health seekers. Imagine whether they would ever encounter such information density and complexity in any other situation in their everyday experience (other than on the Web).

• As a reality check, assume the health seeker is a person concerned with an immediate, perhaps painful experience at the time of information seeking.

• Consider the disruptions and confusions a person may experience and whether the site’s values and priorities differ noticeably from those of a health seeker.

• Ask whether the information architecture presents an optimal model given the total competition for limited attention.

• Recognize that every large-scale information service presents design dilemmas as it grows. With more customers, sponsors, and content, every feature and link creates a claim on limited real estate.

Methods: Consumer Service Design Research

Three models help in selecting research methods for understanding people, their behavior, and their thinking:

• Systems: healthcare applications and processes, from websites to the institutional system

• People: the range of personal and social identities that change in health situations

• Methods: the types and functions of design and research in these domains

The “consumer” context in healthcare is not that of a retail consumer. Design research for consumer healthcare requires a closer engagement with people’s everyday activities than for health practice or education. Choose methods that help develop an understanding of the complexity and problems of the everyday lives in which people make health choices.

In consumer research, the most typical research methods are not design or innovation methods, but are market and business oriented. In consumer healthcare design, both families of methods are needed, along with scientific social research (e.g., well-designed hypothesis-testing surveys or ethnography). Typically, exotic innovation methods are not called for in low-risk and broad-market consumer services, which serve a wide range of popular content needs. Method selection and use should be a judgment based on the product offering, its context with consumer health seekers, and the possible access to real users to deploy the research technique.

Table 2.2 lists common consumer-level innovation research methods and their relative applicability across four canonical phases of deployment. The remarks in bold indicate the most prevalent or recommended use of the method in consumer-oriented research.

The selection of a design research method in a consumer health context is contingent on project goals and product outcomes. In a consumer world, the primary goals are to reach the right health-seeking consumers and to satisfy their information and action goals. The consumer context always raises the problem of representative users—in a large unknown user base, research participants are always proxies and not committed users. The lack of a meaningful sample and the need for validity can confound the outcomes of using a single method. Multiple methods are nearly always recommended. Of these methods, the technique discussed here is the experience critique, a variation of heuristic evaluation.

Experience Critique

The experience critique is a hybrid technique developed from methods of heuristic review and interpretive assessment. The method provides a validated tool for rapidly evaluating an interactive service. It extends the classical heuristic review with an empathic framework for relating an interactive experience to a persona’s information-seeking behavior and activities. Informed by systems thinking, experience critiques evaluate the systemic relationships of an interface to the user’s practice and needs. Yet experience critiques are simple enough for practitioners to modify as a practical technique for service or information design applications. The method is based on:

• The methodology of heuristics (especially Werner Ulrich’s critical system heuristics7).

• The method of adapted heuristic evaluation (developed by Jakob Nielsen8).

• The technique (way of doing the method) of experience critique, an expert review with evaluative questions.

(For more on Ulrich and Nielsen, see the sidebar on page 53.)

Experience critiques help a product team evaluate usability and experience issues from multiple perspectives to support interface and feature decision making. The process is intended as an early-stage research exercise for engaging multiple stakeholders meeting the selection requirements of the innovation of interest (e.g., your personas).

The experience critique delivers a collaborative review of a service or system with prioritized assessments and both expert and user value judgments. Typical applications of the technique include evaluation of product portfolios, websites, or Web services; multiperspective review of an existing service for a planned redesign; and user experience audits.

TABLE 2.2 CONSUMER DESIGN AND MARKET RESEARCH METHODS

Consumer design research methods |

Stage 1: Ideation and market analysis |

Stage 2: Research and concept design |

Stage 3: Product development |

Stage 4: Beta and launch |

Market surveys |

Important |

Critical |

A little too late |

Good for assessing market response |

Focus groups |

A little early |

OK, but not sole method |

Too late, except for pricing |

|

Direct customer feedback |

|

Initial product idea from users |

Useful for validation |

Are we on track? |

Sales and service feedback |

Address emerging market issues |

Useful to know desired features |

|

Help with early feedback from beta |

Customer demonstrations |

Is product acceptable? |

Interactive prototype demo |

Useful for validation |

|

Concept testing |

Generate concepts |

Build and test concepts |

Compare concepts to product |

|

Heuristic evaluation/experience critique |

Very helpful; analyze existing sites and products |

Helpful; analyze and compare concept with current product |

|

|

Usability evaluation |

|

Usability testing of current product to set baseline |

Early product tests |

The earlier the better |

Web surveys |

|

Gather and evaluate ideas |

|

Helpful for early release feedback |

Participatory/generative methods |

Gather range of ideas and latent needs |

Create and elaborate on concepts |

|

|

Contextual inquiry user interviews |

Very helpful; fit concept to user need |

Combine with concept walkthrough |

|

|

A group of appropriate experts are identified and invited to participate in a critical review process. This reviewers’ circle performs individual reviews and audits, and the coordinator collects and integrates the reviews and convenes a live dialogue about the findings. The critique asks each reviewer to consider two perspectives—their own domain of expertise and that of a selected user persona. By explicitly representing goal states and values, a critical evaluation is carried out on behalf of that desired experience.

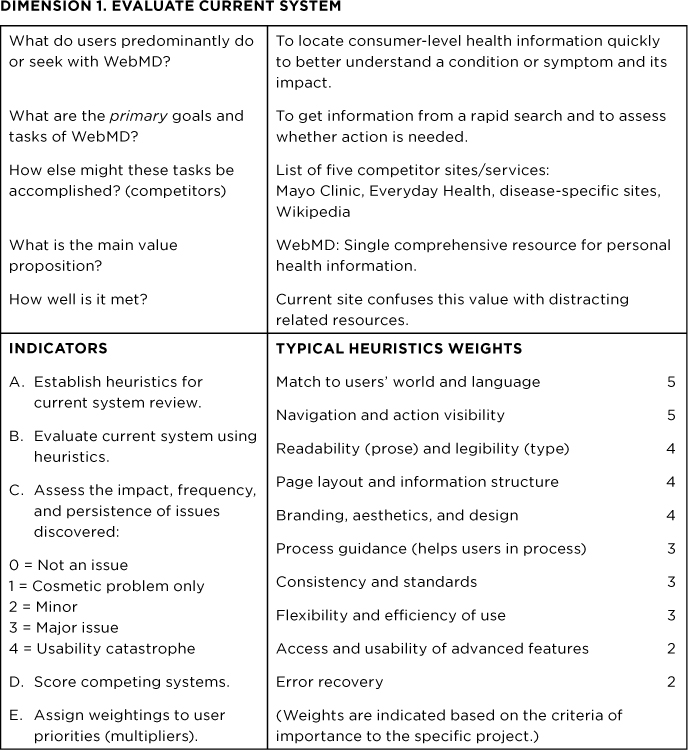

The experience critique identifies four dimensions, some questions that probe each dimension, and indicators for an empathic design inquiry (Table 2.3). Indicators are measures by which each evaluator scores the dimensions and questions (variables) for each factor being assessed.

TABLE 2.3 EXPERIENCE CRITIQUE PROCESS FRAMEWORK

Dimension |

Empathic inquiry |

Indicators |

1. Current system (as is) |

Describe your current goals and practices. |

Evaluate current system |

2. Relevant system values |

What do you consider a good experience? |

Open-ended or comparative feature evaluations |

3. Ideal system |

Describe the ideal system from a user’s perspective. |

Provide guidelines |

4. Ideal values |

Identify ideal values applicable to the system of concern. |

Values scale assessment |

A critique examines user values and needs, as well as system functions and interactions, from an external and detached perspective. As an analytical process, the critique allows the design team to deconstruct elements of a service and evaluate them from both an expert and a consumer/human-centered perspective.

Conducting the Experience Critique

An experience critique is a coordinated process guided by a research leader and managed in five main steps:

- The conceptual framework is used by the coordinator as a reference for ensuring the critical variables are identified and selected as questions in a review template.

- A template is designed as an electronic file and provided to reviewers as a survey form, along with instructions for conducting an individual review of a system or service.

- After individual reviewers conduct their personal critique of a service or system, the individual surveys are aggregated into a common review, and findings are presented and discussed in a roundtable review.

- The coordinator annotates the compiled report with findings from the roundtable, including strategic recommendations and solutions for identified interaction or usability problems.

- The coordinator provides the comprehensive experience critique as a formal, actionable review of the service.

In step 1, the framework maps the priorities and objectives of the review or audit in a template such as the example shown in Figure 2.3. Heuristics are selected based on their value in the review, and weights are assigned to heuristics based on user, system, or market goals.

The results of a combined experience critique, based on heuristic evaluation, supports stakeholders and designers to jointly make grounded assessments of not just usability, but the artifacts and services.

FIGURE 2.3

An experience critique review template. This example shows how an expert reviewer might evaluate WebMD.

• Designers in other fields may not need to specify methods appropriate to the domain, but in the high-risk world of healthcare, it helps to have grounding in human factors and empirical methods. Methods such as the experience critique incorporate the best of both worlds.

• If the scientific worldview does not represent your stance toward knowledge, refresh your understanding of both evidencebased research and design methods, as these are essential to bringing real innovation to healthcare problems.

• Become conversant with a sufficient variety of methods in order to become method agnostic, allowing you to choose the right research technique for the problems and opportunities you face. Selecting the best methods for the problem is a design process in itself.

• There are many appropriate methods for conducting evaluations of processes and systems in healthcare, representing an extensive body of methods on their own. The methods identified in this book are used in practice, but are not recommended as sufficient to all situations.