Chapter 8

Your Best Guess: The Interest Rate Parity (IRP)

In This Chapter

![]() Examining the relationship between interest rate parity and the MBOP

Examining the relationship between interest rate parity and the MBOP

![]() Deriving the interest rate parity

Deriving the interest rate parity

![]() Estimating the forward rate

Estimating the forward rate

![]() Understanding the difference between covered and uncovered interest arbitrage

Understanding the difference between covered and uncovered interest arbitrage

![]() Knowing when an arbitrage opportunity exists

Knowing when an arbitrage opportunity exists

This chapter and Chapter 9 aim to accomplish similar goals. Whereas the theoretical models of Chapters 5, 6, and 7 predict the direction of the change in the exchange rate (appreciate or depreciate), the concepts of interest rate parity (IRP) in this chapter and purchasing power parity (PPP) in the next chapter seek to attach a number to the direction of change in the exchange rate. In other words, Chapters 8 and 9 help you not only identify appreciation of the dollar, for example, but also quantify that appreciation.

Although this quantification is an accomplishment, actual changes in exchange rates may not reflect the IRP-suggested changes every time you observe them. The same is true for the subject of Chapter 9, PPP. Therefore, both the IRP and the PPP give you a “best guess” regarding the direction and size of the change in the exchange rate.

This chapter’s subject, the IRP, explains the changes in the exchange rate based on the interest rate differential between two countries. Understand that the IRP is a long-run relationship between nominal interest rates and changes in the exchange rate. Not every change in the exchange rate can be explained based on the interest rate differential.

This chapter also relates the IRP to the MBOP (monetary approach to balance of payments). The IRP and the MBOP involve different interest rates — nominal and real, respectively. A helpful guide to making the connection between the IRP and the MBOP is the International Fisher Effect (IFE).

Finally, this chapter examines the arbitrage opportunities based on the IRP. You can use the IRP to make profits, which is called the covered interest arbitrage. The concept of covered interest arbitrage is similar to the arbitrage examples in Chapter 3. This chapter helps you understand the difference between uncovered and covered interest arbitrage.

Tackling the Basics of Interest Rate Parity (IRP)

This section sets the stage for the IRP without explicitly talking about it. In fact, you need to be aware of three related subjects before you can understand the IRP and work with it. First, the general concept of the IRP relates the expected change in the exchange rate to the interest rate differential between two countries. This concept may ring a bell if you’ve already read Chapters 6 and 7. Therefore, this section examines the differences between the MBOP and the IRP at a general level. Second, understanding the concept of the International Fisher Effect (IFE) is helpful for understanding the IRP–MBOP relationship. Third, the IRP includes the concept of a forward rate as it is observed on a forward contract. This section discusses forward contracts and forward rates before moving on to the IRP.

Differences between IRP and MBOP

The IRP relates the interest rate differential to the change in the exchange rate. In Chapters 6 and 7, the MBOP seems to be doing the same. What’s the difference?

Recall the parity condition in the MBOP (see Chapter 6 if you need a refresher):

Here, r$, r€,

![]()

and

![]()

denote the real interest rate on the dollar-denominated security, the real interest rate on the euro-denominated security, the expected dollar–euro exchange rate, and the spot dollar–euro exchange rate, respectively. The equation implies that the real return on the dollar-denominated security equals the expected real return on the euro-denominated security in dollars. When this equality holds, the foreign exchange market is in equilibrium. In other words, investors are indifferent between the dollar- and euro-denominated securities.

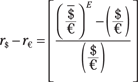

After this quick reminder, you can reorganize the parity equation so that its left side is the difference between the real interest rates in two countries:

The IRP relates the interest rate differential to the expected change in the exchange rate, and this equation from the MBOP seems to do the same thing. At this point, the MBOP and the IRP sound similar. What’s the difference between them?

First, when the MBOP talks about the interest rate differential, it means the difference in two countries’ real interest rates. The IRP is also interested in the difference between interest rates as a predictor for changes in the exchange rate, but the IRP thinks in terms of nominal interest rates.

Second, whereas the MBOP uses the concept of an expected exchange rate, it doesn’t specify how you can measure it. The IRP, on the other hand, uses the forward rate as indicated on a forward contract to get a numerical estimate for the expected change in the exchange rate.

Before introducing the IRP, the next two sections examine the International Fisher Effect (IFE) and forward contracts. The discussion of the IFE helps you understand the compatibility of real interest rates in the MBOP with nominal interest rates in the IRP. Having a basic knowledge of forward contracts is helpful for understanding the forward rate used by the IRP.

The International Fisher Effect (IFE)

The IFE is helpful in finding the relationship between the MBOP and its use of real interest rates, and the IRP and its use of nominal interest rates. Recall the Fisher equation (used in Chapter 5):

![]()

Here, r, R, and π imply the real interest rate, the nominal interest rate, and the inflation rate, respectively. According to the Fisher equation, the real interest rate equals the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

Therefore, if the MBOP and the IRP use the real and nominal interest rate differential in two countries, the difference between these two types of interest rates is the inflation rates in these countries.

The IFE suggests that investors expect the same real return in every country. To keep the real return the same in every country, nominal interest rates should adjust to the changes in the inflation rate. For example, as inflation rates increase, nominal interest rates increase as well, to keep real returns the same.

Therefore, the discussion in this section shows that even though the MBOP and the IRP use the real and nominal interest rates, their approach to the interest rate differential between countries is related through the International Fisher Effect.

IRP and forward contracts

Another difference between the MBOP and the IRP is how they define the expected exchange rate. In the MBOP, the expected exchange rate is included in the parity equation. In Chapters 6 and 7, the expected exchange rate reflects investors’ expectations regarding the exchange rate some time from now. In fact, in exercises provided in Chapter 7, investors adjust their exchange rate expectations upward or downward. However, the MBOP does not explicitly provide any tools that can quantify the expected exchange rate.

The IRP quantifies the expected exchange rate using forward contracts. Forward contracts are an example of foreign exchange derivatives. Chapter 10 examines foreign exchange derivatives in detail. But for now you can think of foreign exchange derivatives as financial contracts where you lock in a specific exchange rate today for a future transaction in currencies (buying or selling of currencies).

A forward contract is an example of a foreign exchange derivative. It allows you to trade one currency for another at some date in the future at an exchange rate specified today. Typically, you get a forward contract from a bank that is engaged in foreign exchange transactions. A forward contract includes the forward rate (the exchange rate on the forward contract), the amount of currency to be bought or sold, and the transaction date. Forward contracts are binding, in the sense that there is an obligation to buy or sell currency at the agreed price for the agreed quantity on the agreed transaction day.

The forward rate may be a good approximation of the expected exchange rate in the bracket of the parity equation in the MBOP. You might expect that a bank considers the current and expected values of the relevant variables for the exchange rate in both countries and quote a forward rate to you. Therefore, in the MBOP and in terms of the dollar–euro exchange rate, the percent change between the spot rate at time t and the expected exchange rate (or the i-period ahead future spot rate) at time t+i is:

If you use the forward rate instead of the expected exchange rate, the percent change in the exchange rate includes the forward rate and the spot rate:

Working with the IRP

This section derives the IRP and shows how the relationship between the change in the exchange rate and the nominal interest rate differential is established. It also introduces the terminology of forward discount or forward premium, which implies the change in the exchange rate. I also give you numerical examples so you can work with the IRP.

Derivation of the IRP

Suppose that you consider investing in the home or foreign country for one period. It means that you have some amount of money now (present value or PV) and, given an interest rate, you want to make some amount of money in the future (future value or FV). Chapter 3 shows the basic relation between PV and FV for one period as:

![]()

Because you know how much money you have (PV) and what the interest rate (R) is now, the unknown is how much money you will make in the future (FV). You rewrite the above formula to have the unknown variable in the left-hand side and get:

![]()

Here, RH and (1+RH) are the nominal interest rate and the interest factor (1+RH) in the home country (H), respectively. For simplicity, assume a $1 investment so that you can simplify your (dollar) earnings to the following:

![]()

Similarly, your (euro) earnings in the foreign country by investing €1 in Eurozone are shown here:

![]()

Here, RF and (1+RF) imply the foreign country’s (F) nominal interest rate and interest factor (in this case, Eurozone’s), respectively.

You can’t directly compare RH and RF or

![]()

because the home and foreign country’s interest rates are denominated in different currencies. Therefore, you need a conversion mechanism.

You can convert your earnings in euro into dollars by multiplying the interest factor in foreign currency with the percent change in exchange rate. But in order to calculate the percent change in the exchange rate, you need to know the current exchange rate and the expected exchange rate. While the current exchange rate is observable, there is no explicit series called expected exchange rate. Therefore, you need a measure for the expected exchange rate. The exchange rate on a forward contract (namely, the forward rate) would be a good proxy for the expected exchange rate.

Therefore, express the nominal version of the MBOP’s parity condition as follows:

![]()

In this equation, F and S are the forward rate and spot rate, respectively. You can further write the forward rate (F) in a way that shows the relationship between F and S:

![]()

This equation states that the difference between the forward rate and the spot rate is related to a factor ρ (rho). The variable ρ can be interpreted as the percentage difference between the forward rate and the spot rate. Inserting the previous definition of the forward rate

![]()

and eliminating the spot rate in the bracket of the equation, you have:

![]()

This equation is a different way of expressing interest rate parity (introduced in Chapter 6). It implies that investors are indifferent between home and foreign securities denominated in home and foreign currencies if the nominal return in the home country equals the nominal return in a foreign country, including the change in the exchange rate.

Look at this equation also from the viewpoint of which variables are known and which variable should be calculated. In the equation, you observe the home and foreign nominal interest rates and want to know what ρ is. Therefore, you divide both sides by (1+RF) and find

![]()

or

![]()

Conceptually, ρ implies the percent change in the exchange rate. Because the previous derivation was based on the change between the forward rate and the spot rate, you refer to ρ as a forward premium or forward discount.

The terms forward premium and forward discount refer to the other currency. You can explain this by considering the sign of ρ. Clearly, ρ can be positive or negative. If the home nominal interest rate (RH) is larger than the foreign nominal interest rate (RF), the ratio of the home and foreign interest factor [(1+RH)/(1+RF)] becomes larger than 1, which makes ρ positive. Because higher nominal interest rate in a country is consistent with higher inflation rates, a positive ρ is forward premium on the foreign currency.

If the home nominal interest rate (RH) is lower than the foreign nominal interest rate (RF), the ratio of the home and foreign interest factor [(1+RH)/(1+RF)] becomes less than 1, which makes ρ negative. Because lower nominal interest rates in a country is consistent with lower inflation rates, a negative ρ is forward discount on the foreign currency.

Calculation of forward discount and forward premium

![]()

Note that ρ is negative, and you interpret the result as 8.56 percent forward discount on the Turkish Lira.

Suppose you observe that the spot dollar–Turkish lira exchange rate is $0.43 per Turkish lira. Now you know ρ and the spot exchange rate. Therefore, you can calculate the IRP-suggested forward rate (FIRP):

![]()

The IRP-suggested forward rate implies an appreciation of the dollar against the Turkish lira, which makes sense. The Turkish T-bill rate is higher than that of the U.S., which implies a higher expected inflation rate in Turkey.

The previously mentioned forward rate is called the IRP-suggested forward rate for good reason. The concept of IRP enables you to come up with an expected change in the exchange rate (ρ) by looking at the interest rate differential between two countries. Then, when you apply the expected change in the exchange rate to the spot rate, you come up with your best guess of the expected change rate. You should go through these calculations and have your best guess regarding the expected exchange rate ready before you talk to a bank about the bank’s forward rate. In the next section, you’ll see the relevance of a discrepancy between the IRP-suggested forward rate and the bank’s forward rate.

![]()

The result indicates a 1.37 percent premium on the Japanese yen. Suppose that you observe the spot dollar–yen exchange rate as $0.011 per yen. Plug in ρ and the spot exchange rate into the equation that indicates the IRP-suggested forward rate (FIRP):

![]()

In this case, the IRP-suggested forward rate implies depreciation of the dollar because of higher nominal interest rate in the U.S.

Now you’re a master at calculating and interpreting ρ! The next section focuses on applying this knowledge to speculation opportunities.

Speculation Using the Covered Interest Arbitrage

You can use the IRP to make profits — and everyone likes profits! Speculation involves buying and selling things to make profits. In this case, you are buying and selling currencies. Buying low and selling high is also the way to make money through currency speculation. Flip over to Chapter 3 and check out the speculation examples there.

To see the difference between the speculation exercises in Chapter 3 and the ones in this chapter, you have to understand the difference between covered and uncovered interest arbitrage.

Covered versus uncovered interest arbitrage

In Chapter 3’s exercises, the speculator didn’t have a forward contract to exchange currency at a future date. He just had his expectations regarding the future spot rate and used the future spot market to exchange currency.

Suppose that an American investor wants to make use of the differences in interest rates on the dollar and the euro, as well as the expected change in the dollar–euro exchange rate between now and sometime in the future by putting his money in a euro-denominated security. Therefore, he buys euros today, invests in the security, and, at maturity, sells his euros and converts them into dollars.

If this speculator relies on his expectations regarding the future spot rate to sell his euros and, therefore, sells those euros in the future spot market, he engages in an uncovered interest arbitrage: The future spot rate can be anything, and he’s not hedged against possible changes in the future spot rate.

The IRP, however, assumes that the speculator gets a forward contract to exchange foreign currency in the future. Having a forward contract doesn’t solve all his problems, as the discussion of foreign exchange derivatives shows in Chapter 10. Nevertheless, a forward contract can limit a speculator’s exposure to unexpected and potentially large changes in future spot rates. When a speculator has a forward contract with a predetermined forward rate at which he’ll sell currency in the future, this time he engages in covered interest arbitrage.

Now that you know about the difference between uncovered and covered interest arbitrage, there is one more topic to discuss before moving to numerical exercises. This topic is related to the question when a speculator makes a profit based on the covered interest rate arbitrage.

In order to think about your profit opportunities using the IRP or the covered interest arbitrage, consider the previous calculations of ρ and the IRP-suggested forward rate. ρ is calculated based on the interest rate differential between countries. When you plug your calculated ρ into the forward rate formula, to separate it from the bank’s forward rate, you call it the IRP-suggested forward rate.

Suppose you collect data about the relevant interest rates and the spot exchange rate. You go to the bank and ask about its forward rate. If the IRP-suggested forward rate is the same as the bank’s forward rate, the IRP holds; neither domestic nor foreign investors have an opportunity to engage in covered interest arbitrage and make profits. In other words, neither investor can use covered interest arbitrage to enjoy higher returns than the ones provided in their home countries. In this case, the change between the forward rate and the spot rate offsets the interest rate differential between two countries.

The IRP does not hold if the bank’s forward rate does not reflect the interest rate differential. In other words, when you go to the bank and ask about its forward rate, its forward rate may be different than the IRP-suggested forward rate. In this case, either you or a foreign speculator can earn excess profits by investing in securities in the other country, but, under normal circumstances, not both of you.

Covered arbitrage examples

This section gives two numerical examples. The first one is related to the U.S. and Turkish T-bill example, for which you already calculated ρ. The second example looks at the covered interest arbitrage from both home and foreign investors’ points of view. It also introduces a discussion about how you can decide which investor will have excess returns from a covered investment in foreign securities by observing the interest rate differential and the bank-suggested ρ.

Now you go to the bank with this information and ask about its one-year forward rate. Suppose that the bank’s forward rate is $0.41. Clearly, the bank’s forward rate is higher than the IRP-suggested forward rate. The bank’s forward rate implies a lower rate of appreciation in the dollar against the Turkish lira (TL). To see this clearly, calculate the bank-suggested ρ:

![]()

The bank’s forward rate implies a forward discount of 4.65 percent on the Turkish lira, which is lower than the IRP-suggested forward discount of 8.56 percent. Because the IRP does not hold, you may have an opportunity to enjoy excess returns in this case. Assuming that you start with $100,000, you go through the following steps:

1. Get a forward contract to sell Turkish lira a year from now at the forward rate of $0.41.

2. Convert $100,000 into Turkish lira in the spot market: $100,000 / $0.43 = TL232,558.14.

3. Buy T-bills denominated in Turkish lira and hold them for a year: 232,558.14 × (1.11) = TL258,139.53

4. Sell TL258,139.53 on the forward contract: 258,139.53 × 0.41 = $105,837.21.

Make sure that you make more money from covered interest arbitrage than you would have made in the home country. (Otherwise, why would you go through so much trouble?) You started with $100,000 and you made $105,827.21 by investing in Turkish securities. If you invested in U.S. securities, you would have made only $101,500 ($100,000 × 1.015). You can also calculate your rate of return from covered interest arbitrage and compare it to the home country’s rate of return:

![]()

You can enjoy a return of almost 5.84 percent, which is higher than what you would have earned in the U.S. (1.5 percent). Now you’ve verified that covered interest arbitrage works for you (home country investor) in this example.

![]() St = ($/€)t = $1.31

St = ($/€)t = $1.31

![]() Ft = ($/€)t = $1.69 (one-year forward rate)

Ft = ($/€)t = $1.69 (one-year forward rate)

![]() RUS = 0.16 percent (one-year nominal interest rate on a dollar-denominated U.S. security or RH)

RUS = 0.16 percent (one-year nominal interest rate on a dollar-denominated U.S. security or RH)

![]() RE = 0.60 percent (one-year nominal interest rate on a euro-denominated Eurozone security or RF)

RE = 0.60 percent (one-year nominal interest rate on a euro-denominated Eurozone security or RF)

Given this information, you can answer the question of whether the IRP holds. Then assuming an American and a European investor with $1,000,000 (the European investor has the euro-equivalent of $1,000,000 at the spot rate), you also can demonstrate which investor would be better off investing in foreign securities if the IRP doesn’t hold.

Remember, covered interest arbitrage is profitable only when the IRP doesn’t hold. To test whether the IRP holds, determine the IRP-suggested forward premium that should exist for the dollar–euro exchange rate:

![]()

The sign of ρ is negative, and the calculation indicates a 0.44 percent discount on the euro. Therefore, we expect the forward rate to be:

![]()

The IRP-suggested forward rate is $1.30, and it’s lower than the actual forward rate of $1.69. In fact, the bank’s forward rate-suggested ρ is:

![]()

The bank’s forward premium on the euro is about 29 percent, which contradicts the forward discount suggested by the IRP. Therefore, the IRP does not hold, and one of the investors has an opportunity to make excess profits based on the covered interest arbitrage.

First, look at it from the American investor’s point of view. The American investor:

1. Gets a forwards contract to sell euros a year from now at $1.69.

2. Converts dollars to euros in the spot market: $1,000,000/$1.31 = €763,358.78.

3. Invests in a one-year euro-denominated security. In a year, he will have €763,358.78 × 1.006 = €767,938.93.

4. Sells euros at the forward rate and receives €767,938.93 × 1.69 = $1,297,816.79.

The American investor’s rate of return in dollars is:

![]()

Covered interest arbitrage works for the American investor because his yield from investing in Euros is about 30 percent, which is much higher than the U.S. interest rate (0.16 percent).

Now look at the situation from the European investor’s point of you. The European investor:

1. Gets a forward contract to sell dollars a year from now at $1.69.

2. Converts euros to dollars in the spot market: €763,358.78 × $1.31 = $1,000,000.

3. Invests in a one-year dollar-denominated security. In a year, he will have $1,000,000 × 1.0016 = $1,001,600.

4. Sells dollars at the forward rate and receives $1,001,600 / $1.69 = €592,662.72.

The European investor has a loss: €592,662.72 – €763,358.78= -€170,696.06.

The covered interest arbitrage does not work for the European investor.

Graphical treatment of arbitrage opportunities

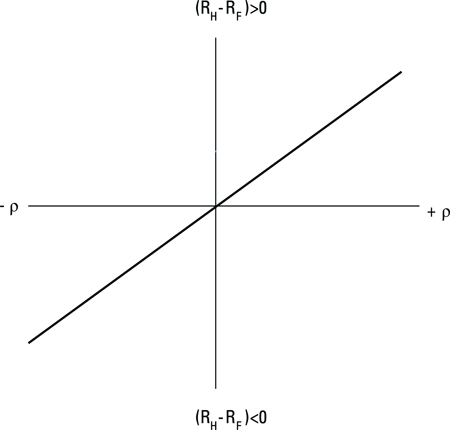

You can use a graphical way to know which investor, home or foreign, can make use of the covered interest arbitrage to earn excess returns. Figure 8-1 illustrates this possibility.

In Figure 8-1, you see the approximate interest rate differential between home and foreign nominal interest rates on the y-axis, which can be positive or negative. Rather than using the formula for IRP, which is

![]()

you can use the following approximation (preferably for small differences between two countries’ interest rates):

![]()

In Figure 8-1, on the y-axis, you see the interest rate differential. The x-axis indicates the forward premium or discount, as measured by ρ. You also know that ρ can be positive (forward premium on foreign currency) or negative (forward discount on foreign currency), which is indicated by the positive and negative x-axis.

Figure 8-1: Graphical representation of the IRP.

The 45-degree line indicates when the IRP holds. Assuming no transaction costs, the IRP holds when the forward premium or discount equals the interest rate differential.

However, more clarity is needed on which forward premium or discount is relevant here: the one that reflects the bank’s ρ. If the bank’s forward rate reflects the IRP-suggested premium or discount, you’re on the 45-degree line. This line indicates that the IRP holds; therefore, neither investor has an opportunity to make excess returns based on covered interest arbitrage.

What happens when the IRP doesn’t hold? Look back to the last numerical example with American and European investors. In that example, the nominal interest rate differential between the dollar- and euro-denominated securities is -0.44 percent (0.16 – 0.60). However, you calculated the bank’s implicit forward premium on the euro to be +29. Therefore, in terms of this example, you are certainly not on the 45-degree line in Figure 8-1: You’re below this line and in the fourth quadrant (because of negative interest rate differential and positive ρ).

Generally, the area below the 45-degree line implies the area where the American investor (home country investor) earns excess profits from covered interest arbitrage. Note that this area includes parts of the first and third quadrants and the entire fourth quadrant. If the interest rate differential and ρ fall into the area above the 45-degree line, including the parts of the first and third quadrants and the entire second quadrant, the European investor (foreign country investor) earns excess profits.

Determining Whether the IRP Holds

The IRP indicates a long-run relationship between interest rate differentials and forward premium or discount. Although at any given time this relationship may not hold, if appropriate estimation techniques are applied to long-enough data, you would expect the results to verify the IRP.

In reality, things don’t work this smoothly. Factors interfere with the empirical verification of the IRP. In the following section, I show the interest rate–exchange rate relationship in reality.

Empirical evidence on IRP

The empirical verification of the IRP depends upon the approach. Empirical studies using forward rates seem to have a better chance of showing that the IRP exists. In other words, empirical results suggest that deviations from the IRP aren’t large enough to make covered interest arbitrage profitable.

However, when empirical studies use interest rate differentials between two countries, the results suggest that interest rates aren’t consistently good predictors of changes in exchange rates, especially larger ones.

The results also differ depending on whether we try to predict short- or long-term changes in exchange rates. Empirical evidence indicates that macro-economic fundamentals have little explanatory power for changes in exchange rates up to a year. In fact, random walk models of exchange rates seem to outperform macroeconomic fundamentals-based models of exchange rate determination. This is not very good news for macroeconomic models, if you consider what a random walk model is. A random walk model of exchange rates calculates the next period’s exchange rate as today’s exchange rate with some unpredictable error.

Factors that interfere with IRP

A variety of risks associated with a currency make a security denominated in this currency an imperfect substitute to another country’s security.

The term political risk includes different categories of risks, which makes securities denominated in different currencies imperfect substitutes. Certain domestic or international events may motivate governments to introduce restrictions on incoming foreign portfolio investments. Or particular events or policies in a country may increase the country’s default risk, as perceived by foreign investors. Likewise, differences in tax laws may cause concern among investors regarding their after-tax returns.

Other reasons also exist. Sometimes markets’ observed preference for certain currencies cannot be explained based on interest rates differentials. The Swiss franc is a good example in this respect. Usually when most developed economies go through a recession, the Swiss franc appears to be the go-to currency, even though interest rate differentials suggest otherwise. This fact may reflect the liquidity preference of some international investors during periods of slower global growth.

Additionally, there is the so-called carry trade. It means borrowing in a low-interest-rate currency and investing in a high-interest-rate currency. Carry trade is very risky and is not consistent with the IRP. This kind of international investment appreciates the currency of the country with higher nominal interest rates, which goes against the predictions of the IRP.

All of these factors contribute to the weakening of the IRP-suggested relationship between interest rates and changes in the exchange rate.

Suppose investors expect a 3 percent real return to domestic investment in all countries. Of course, the international comparison is based on a security of comparable risk and maturity. Suppose that the U.S. nominal interest rate and inflation rate are 5 percent and 2 percent, respectively. If the U.K.’s inflation rate is 1 percent and the exchange rate isn’t expected to change, U.K. investors would look for a pound-denominated security whose nominal interest rate is 4 percent. (There’s an exchange rate dimension in this example, which becomes important in the upcoming sections of this chapter. This exchange rate dimension implies that a real return of 3 percent to domestic investors does not necessarily imply a real return of 3 percent to foreigners in this example.)

Suppose investors expect a 3 percent real return to domestic investment in all countries. Of course, the international comparison is based on a security of comparable risk and maturity. Suppose that the U.S. nominal interest rate and inflation rate are 5 percent and 2 percent, respectively. If the U.K.’s inflation rate is 1 percent and the exchange rate isn’t expected to change, U.K. investors would look for a pound-denominated security whose nominal interest rate is 4 percent. (There’s an exchange rate dimension in this example, which becomes important in the upcoming sections of this chapter. This exchange rate dimension implies that a real return of 3 percent to domestic investors does not necessarily imply a real return of 3 percent to foreigners in this example.) The following numerical examples assume no transactions costs such as fees, bid-ask spreads, and so on.

The following numerical examples assume no transactions costs such as fees, bid-ask spreads, and so on.  A word of caution: Some of the examples show large rates of returns. The probability of enjoying such high returns in real life is small.

A word of caution: Some of the examples show large rates of returns. The probability of enjoying such high returns in real life is small.