American Airlines and Citibank: Leading the Charge for Frequent Flyer Miles

“I'm not one to recommend taking on any new credit card lightly,” says Joe Brancatelli, publisher of business travel Web site www.joesentme.com, “but once in a while, an offer comes along that's irresistible.”a

“As long as [the airlines] don't mess with the consumer perception of the value in their programs, they're a perpetual money-making machine.” –Gary Leff, Inside Flyer.c

That's exactly the reaction American Airlines and Citibank®, paired by a mutual interest in protecting profits during an economic slump, hope consumers have to their co-branded Citi®/AAdvantage® credit card. The card, launched in 1987, provides casual customers and frequent travelers alike the opportunity to earn American Airlines AAdvantage® miles with a simple promise: Earn miles for everyday purchases.

Cardholders earn one mile per dollar spent on purchases with the card, with multipliers or accelerators invoked for promotional special offers–for example, 2 miles per dollar spent on all grocery purchases for a limited time. But the biggest draw for American customers is often the signing incentive, which is typically a compelling offer of American Airlines AAdvantage bonus miles, awarded for achieving a pre-determined (but reasonable) spending threshold within the first several months of having the card (e.g., 30,000 bonus miles after spending $750 within 4 months of becoming a cardmember).

Beyond the miles, monthly mailings, and marketing hype, it's a strong example of a cross-industry alliance that provides mutual benefit to partners in volatile and highly competitive markets. Both partners know that the allure of destinations unknown can powerfully motivate consumers. Citi realizes thousands of new customers (or in some cases, existing customers adding a second card to their wallet), many funneling much more of their monthly spending through a Citi credit card than they'd ever planned.

American benefits from a much-welcomed influx of cash–Citi purchases AAdvantage miles in bulk at an undisclosed price that generally favors American.b And the promise of “miles for every purchase” keeps customers actively engaged in a relationship with American: cardholders are suddenly taking a second look at flying when they might ordinarily drive, or choosing American over a better-priced competitor.

Given the competition in both the airline and financial industries, do you think this alliance has what it takes to go the distance? If not, which partner would be at a greater disadvantage if the relationship dissolved?

Quick Summary

- American Airlines and Citibank, a partnership initiated in 1987, release a co-branded Citi®/AAdvantage® credit card.

- Along with an initial signing bonus, cardholders earn AAdvantage miles for nearly every purchase they make with the card.

- The partnership is mutually beneficial: Citibank purchases miles in bulk from American Airlines, which in turn provides Citi with new customers through a compelling incentive for members–the promise of travel.

FYI: 52% of frequent flyers polled believe that credit card spending should not qualify customers for elite status.d

how to compete in a changing landscape

17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design

the key point

Organizations use strategy, technology, and design options to respond to opportunities and challenges in their competitive landscapes. The American Airlines and Citibank alliance is but one example. You need to understand the basic linkages among strategy, technology, and design. And it is important to understand how to lead under different environmental circumstances.

chapter at a glance

- Why Are Strategy and Organizational Learning Important?

- What Is Organizational Design, and How Is It Linked to Strategy?

- How Does Technology Influence Organizational Design?

- How Does the Environment Influence Organizational Design?

- How Should the Whole Organization Be Led Strategically?

As the example of the American Airlines-Citibank alliance suggests, executives of leading firms are taking a very sophisticated view of what their firms can do, how they can compete, and who they need as partners to insure success. Today, executives think about choices. What contributions to society should their firms make? How should the firm be positioned in the environment? Can the firm alter the environment in its favor either alone or with others? And how should the whole firm be lead? The key to success is to integrate such choices into an overall pattern—a strategy for success.

Strategy and Organizational Learning

LEARNING ROADMAP Strategy / Organizational Learning / Linking Strategy and Organizational Learning

Strategy

Strategy is the process of positioning the organization in the competitive environment and implementing actions to compete successfully. It is a pattern in a stream of decisions.1 Choosing the types of contributions the firm intends to make to the larger society, precisely whom it will serve, and exactly what it will provide to others are conventional ways in which the firm begins the pattern of decisions and corresponding implementations that define its strategy.

• Strategy positions the organization in the competitive environment and implements actions to compete successfully.

The Strategy Process The strategy process is ongoing. It should involve individuals at all levels of the firm to ensure that there is a recognizable, consistent pattern—yielding a superior capability over rivals—up and down the firm and across all of its activities. This recognizable pattern involves many facets to develop a sustainable and unique set of dynamic capabilities.

Obviously, a successful strategy does not evolve in a vacuum but is driven by the goals emphasized, the size of the enterprise, the nature of the technology used by the firm, and its setting as well as the structure used to implement the strategy. In this chapter, we will emphasize the development of dynamic capabilities via organizational learning as an enduring feature of a successful strategy.

Strategy and Co-Evolution With astute senior management, the firm can coevolve. That is, the firm can adjust to both internal and external changes even as it shapes some of the challenges facing it. Co-evolution is a process,2 and one aspect of this process is repositioning the firm in its setting as the setting changes. A shift in the environment may call for adjusting the firm's scale of operations. Senior management can also guide the process of positioning and repositioning in the environment.

Co-evolution may call for changes in technology. For instance, a firm can introduce new products into new markets. It can change parts of its environment by joining with others to compete. However, senior management must also have the necessary internal capabilities if it is to shape its environment. It cannot introduce new products without extensive product development capabilities or rush into a new market it does not understand. Shaping capabilities via the organization's design is a dynamic aspect of co-evolution. Corning is an example of a firm that effectively innovates and uses partners to commercialize its innovations across the globe.

Corning's Strategy Has a Global Reach

Although Corning is an innovation-driven firm engaged in a variety of advanced materials and technologies, it does not commercialize its new products alone. For instance, it is exploring the development of more effective wafered silicon photovoltaic (PV) cells with Hemlock Semiconductor.

Strategy as a Pattern of Decisions The second aspect of strategy is a pattern in the stream of decisions. In a recent poll of some 750 CEOs, Samuel Palmisano, CEO of IBM, reported that two-thirds of the respondents reported being inundated with change and new competitors. Most saw their primary focus as that of adjusting their firm's processes, management, and culture to the new learning challenges. Most called for collaboration with other firms and suggested that they would emphasize learning to innovate.3

As the environment, strategy, and technology shift, we expect to see changes in the pattern of decisions selected within an organization. For example, IBM was once known as big blue, a button-down, white-shirt, blue-tie-and-black-shoe, second-to-market imitator with the bulk of its business centered on mainframe computers. The company is now a major hub in e-commerce and is on the cutting edge as an integrator across systems, equipment, and service.

Organizational Learning

Organizational learning is the process of acquiring knowledge and using information to adapt successfully to changing circumstances. For organizations to learn, they must engage in knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention in adapting successfully to changing circumstances.4 In simpler terms, organizational learning involves the adjustment of actions based on the organization's experience and that of others. The challenge is doing to learn and learning to do.

• Organizational learning is the process of knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention.

How Organizations Acquire Knowledge Firms obtain information in a variety of ways and at different rates during their histories. Perhaps the most important information is obtained from sources outside the firm at the time of its founding. During the firm's initial years, its managers copy, or mimic, what they believe are the successful practices of others.5 As they mature, however, firms can also acquire knowledge through experience and systematic search.

Mimicry is the copying of the successful practices of others. Mimicry is particularly important to the new firm because (1) it provides workable, if not ideal, solutions to many problems; (2) it reduces the number of decisions that need to be analyzed separately, allowing managers to concentrate on more critical issues; and (3) it establishes legitimacy or acceptance by employees, suppliers, and customers and narrows the choices calling for detailed explanation.

• Mimicry is the copying of the successful practices of others.

A primary way to acquire knowledge is through experience. All organizations and managers can learn in this manner. Besides learning by doing, managers can also systematically embark on structured programs to capture the lessons to be learned from failure and success.6 For instance, a well-designed research and development program allows managers to learn as much through failure as through success.7

How to Improve Process Benchmarking

When learning how to improve an administrative process:

- Define the process by comparing current operations with best practices either inside or outside the firm.

- Develop a plan, identify who will be studied, and determine who will conduct the study, where it will be done, and how it will be conducted.

- Prioritize the findings by ease of implementation and projected benefit, recognizing the differences between the unit to be copied and your current unit.

- Consider the applicability of the proposed changes–do they make sense and can they be applied?

- Discuss implementation with all affected parties and monitor implementation for lessons learned.

Vicarious learning involves capturing the lessons of others' experiences. Typically, successful vicarious learning involves both scanning and grafting.8

• Vicarious learning involves capturing the lessons of others' experiences.

Scanning involves looking outside the firm and bringing back useful solutions. At times, these solutions are applied to recognized problems. More often, these solutions float around management until they are needed to solve a problem.9 Astute managers can contribute to organizational learning by scanning external sources, such as competitors, suppliers, industry consultants, customers, and leading firms.

• Scanning involves looking outside the firm and bringing back useful solutions.

Grafting is the process of acquiring individuals, units, or firms to bring in useful knowledge. Almost all firms seek to hire experienced individuals from other firms simply because experienced individuals may bring with them a completely new series of solutions. Contracting out or outsourcing is the reverse of grafting and involves asking outsiders to perform a particular function. Whereas virtually all organizations contract out and outsource, the key question for managers is often what to keep.

• Grafting is the process of acquiring individuals, units, or firms to bring in useful knowledge.

Information Distribution and Interpretation Once information is obtained, managers must establish mechanisms to distribute relevant information to the individuals who may need it. A primary challenge in larger firms is to locate quickly who has the appropriate information and who needs specific types of information.

Although data collection is helpful, it is not enough. Data are not information; the information must be interpreted. Information within organizations is a collective understanding of the firm's goals and of how the data relate to one of the firm's stated or unstated objectives within the current setting. Unfortunately, a number of common problems often thwart the process of developing multiple interpretations.10 Chief among the problems of interpretation are self-serving interpretations. Among managers, the ability to interpret events, conditions, and history to their own advantage is almost universal. Managers and employees alike often see what they have seen in the past or see what they want to see.

Retention Organizations contain a variety of mechanisms that can be used to retain useful information.11 In addition to individual employees, documents, the internal information systems, and external archives and individuals, organizations can also retain information through their formal structures and ecology.

The organization's formal structure and the positions in an organization are mechanisms for storing information. Landing on the deck of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, for example, is dangerous. There have historically been several accidents. After each accident an investigation is conducted to prevent a similar occurrence. Based on this investigation individuals are trained in specific remedial actions and assigned to specific positions during landings. Over time as each individual trains the next generation of position holders, the Navy retains the lessons learned from prior accidents through these positions.

ETHICS IN OB

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR TACKLES ILLITERACY, TURNS DREAM INTO PROGRESS

There was a time when John Wood was just another, albeit up-and-coming, Microsoft executive. Now he's a social entrepreneur fighting the scourge of illiteracy through a nonprofit called Room to Read. What began as a dream of making a contribution to the fight against illiteracy has become a reality, one that grows stronger each day.

During a successful career as a Microsoft executive, his life changed on a vacation to the Himalayas of Nepal. Wood was shocked at the lack of schools. He discovered a passion that determines what he calls the “second chapter” in his life: to provide the lifelong benefits of education to poor children. He quit his Microsoft job and started Room to Read. So far, the organization has built over 100 schools and 1,000 libraries in Cambodia, India, Nepal, Vietnam, and Laos.

Noting that one-seventh of the global population can't read or write, Wood says: “I don't see how we are going to solve the world's problems without literacy.” The Room to Read model is so efficient that it can build schools for as little as $6,000. Time magazine has honored Wood and his team as “Asian Heroes” and Fast Company magazine tapped his organization for a Social Capitalist Award.

Could You Do It? What social problems do you see in your community, and which of them seems most pressing in terms of negative consequences? Who seems to be stepping forward in the attempt to solve the problems in innovative ways? Where and how might you engage in social entrepreneurship and make a very personal contribution to what is taking place? What, if anything, is holding you back?

The physical structures (or ecology, in the language of learning theorists) are potentially important mechanisms used to store information. For example, a traditional way of ordering parts is known as the “two-bin” system. One bin is always kept in reserve. Once an individual opens the reserve bin, he or she automatically orders replacements. In this way, the plant never runs out of parts.

Linking Strategy and Organizational Learning

As this quick overview of strategy and learning suggests, there are many strategies and many ways to learn. Historically, these two concepts have been discussed separately. Often strategy is linked to economic perspectives of the firm, whereas learning is discussed with organizational change. Today, however, many OB scholars recognize that to compete successfully in the twenty-first century global economy, individuals, units, and firms will need to learn continually. A firm based in a developed nation cannot successfully compete with firms based in developing countries just by being more efficient, any more than an individual in western Europe or North America can afford to work for the same wages as laborers from developing countries.

Production technology now spreads globally; transportation of goods is cheap, and the delivery of many services cuts across national boundaries. However, this does not mean that firms in developed nations are doomed. Firms can know more about their local markets; they can carefully select what they produce, what services they provide, what they buy, and how to build capability. They must learn and use their strategy to provide the necessary balance between exploration and exploitation of new ideas.12 They must be capable of sustained learning at the organizational level to capture the lessons from exploring new technologies and exploiting existing markets.13

It is important to emphasize that sustaining a competitive strategy with consistent learning involves more than just a commitment by individuals; it calls for a systematic adjustment of the organization's structure and processes to alterations in the size and scope of operations, the technology selected, and the environmental setting. The process involved in making these dynamic adjustments is known as organizational design. As illustrated in Finding the Leader in You, old strategies based, for example, on low costs, also call for valuing employees as a basis for learning.

Strategy and Organizational Design

LEARNING ROADMAP Organizational Design and Strategic Decisions / Organizational Design, Age, and Growth / Smaller Size and the Simple Design

Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration.14 It goes beyond just indicating who reports to whom and what types of jobs are contained in each department. The design process takes the basic structural elements and molds them to the firm's desires, demands, constraints, and choices. The choice of an appropriate organizational design is contingent upon several factors, including the size of the firm, its operations and information technology, its environment, and, of course, the strategy it selects for growth and survival.

• Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration for an organization.

For example, IBM's senior management has selected a form of organization for each component of IBM that matches that component's contribution to the whole. The overall organizational design matches the technical challenges facing IBM, allows it to adjust to new developments, and helps it shape its competitive landscape. Above all, the design promotes the development of individual skills and abilities, but different designs stress different skills and abilities. See, for instance, the activities IBM supports for Naoki Abe in its Yorktown Research Center. As we discuss each major contingency factor, we will highlight the design option the firm's managers need to consider and link these options to aspects of innovation and learning.15

Organizational Design and Strategic Decisions

To show the intricate intertwining of strategy and organizational design, it is important to reiterate and extend the dualistic notion of strategy.16 Recall that strategy is a positioning of the firm in its environment to provide it with the capability to succeed. Strategy is also a pattern in the stream of decisions. Here we will emphasize that what the firm intends to do must be backed up by capabilities for implementation in a setting that facilitates success.

Building Research Skills at IBM

Naoki Abe, an IBM research staff member at the Yorktown Research Center, engages in the development of novel machine learning methods and their application in business analytics and optimization. He notes that instead of the machine applying the rules, “we had the machine generate the rules for learning.” His projects will hopefully improve cost-sensitive learning to facilitate business intelligence efforts.

Historically, executives were told that firms had available a limited number of economically determined generic strategies that were built upon the foundations of such factors as efficiency and innovation.17 If the firm wanted efficiency, it should adopt the machine bureaucracy (many levels of management backed with extensive controls replete with written procedures). If it wanted innovation, it should adopt a more organic form (fewer levels of management with an emphasis on coordination). Today the world of corporations is much more complex, and executives have found much more sophisticated ways of competing.

Now many senior executives emphasize the skills and abilities that their firms need to compete and to remain agile and dynamic in a rapidly changing world.18 The structural configuration or organizational design of the firm should not only facilitate the types of accomplishment desired by senior management, but also allow individuals to experiment, grow, and develop competencies so that the firm can learn and can evolve its strategy.19 Over time, the firm may develop specific administrative and technical skills as middle- and lower-level managers institute minor adjustments to solve specific problems. As they learn, so can their firms if the individual learning of employees can be transferred across and up the organization's hierarchy.

Organizational Design, Age, and Growth

Most organizations want to grow and grow old. Growing old also means that the firm has a record of success, has been able to develop an effective strategy, and has been able to learn. However, aging also exposes the firm to a number of adjustment problems.

As organizations grow, the design of the firm needs to be adjusted.20 Large organizations cannot simply be bigger versions of their smaller counterparts. With growth the direct interpersonal contact among all members in an organization must be managed. For instance, when the number of individuals in a firm is increased arithmetically, the number of possible interconnections between these individuals increases geometrically.

The Perils of Growth and Age As organizations age and begin to grow beyond their simple structure, they become more rigid, inflexible, and resistant to change.21 Both managers and employees begin to believe their prior success will continue into the future without an emphasis on innovation or learning. The organization or department becomes subject to routine scripts.

A managerial script is a series of well-known routines for problem identification and alternative generation and analysis common to managers within a firm.22 Different organizations have different scripts, often based on what has worked in the past. In a way, the script is a ritual that reflects the “memory banks” held by the corporation. However, managers become bound by what they have seen. They may not be open to what is actually occurring. They may be unable to unlearn. Few managers question a successful script. Consequently, they start solving today's problems with yesterday's solutions. Managers often initiate small, incremental improvements based on existing solutions instead of creating new approaches to identify underlying problems.

• A managerial script is a series of well-known routines for problem identification and alternative generation and analysis common to managers within a firm.

Overcoming Inertia For large organizations a key challenge in overcoming inertia is eliminating the vertical, horizontal, external, and geographic barriers that block desired action, innovation, and learning.23 These barriers include overemphasizing vertical relations that can block communication up and down the firm; overemphasizing functions, product lines, or organizational units that block effective coordination; maintaining rigid lines of demarcation between the firm and its partners that isolate it from others; and reinforcing natural cultural, national, and geographical borders that can limit globally coordinated action. In breaking down such barriers, the goal is not necessarily to eliminate them altogether, but to make them more permeable.24

There are several major factors associated with the inability to dynamically co-evolve and develop a cycle with positive benefits.25 Beyond inertia is hubris. Too few senior executives are willing to challenge their own actions or those of their firms because they see a history of success. An issue related to inertia and hubris is excessive detachment. Executives often believe they can manage far-flung, diverse operations just through analysis of reports and financial records. They lose touch and fail to make the needed unique and special adaptations required of all firms.

Although inertia, hubris, and detachment are common maladies, they are not the automatic fate of all corporations. Firms can successfully co-evolve. As we have repeatedly demonstrated, managers are constantly trying to reinvent their firms. They hope to initiate a benefit cycle—a pattern of successful adjustment followed by further improvements.26 General Mills, IBM, Cisco, and Microsoft are examples of firms experiencing a benefit cycle. In this cycle, the same problems do not keep recurring as the firm develops adequate mechanisms for learning. The firm has few major difficulties with the learning process, and managers continually attempt to improve knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory.

Smaller Size and the Simple Design

Larger organizations are more complex than smaller firms. The design of small firms is directly influenced by its core operations technology whereas larger firms have many core operations technologies in a wide variety of much more specialized units. While all larger firms are bureaucracies, smaller firms need not be. In larger firms, additional complexity calls for a more sophisticated organizational design. Such is not the case for the small firm. For smaller firms the simple design is most appropriate.

Finding the Leader in You

JIM SINEGAL'S STRATEGY AT COSTCO IS TO NOT FOLLOW THE CROWD

According to CEO Jim Sinegal, “Costco is able to offer lower prices … by eliminating virtually all the frills and costs historically associated with conventional wholesalers…. We run a tight operation with extremely low overhead.”

On the surface it sounds much like most large-box discount retailers who pursue a low-cost strategy in order to effectively compete. So what is the difference? For one, Costco invests in its employees. They pay nearly all full-time employees full benefits, including health care and retirement. Base wages are among the highest in the industry, and the company also promotes from within. It is not at all unusual to find a store manager who started her career with Costco. The emphasis on employees is rare in the discount retail sector. For many competitors, a low-cost strategy means low wages and restricted benefits. And, of course, devaluing employees means not learning much from employees.

How does Costco do it? Costco stores have a comparatively limited range of items, which cuts carrying costs. Most Costco stores have, at any given time, 5,000 items compared to about 100,000 for Walmart. Costco also tends to carry a greater number of higher-end products with very low margins to stimulate store excitement. As a result, Costco is the fifth largest retailer in the United States, with over 53 million cardholders and 250,000 employees. With global sales approaching $75 billion, Costco currently ranks 29th on the Fortune global 500 list.

In the short term Costco could probably make more money with lower wages and benefits. But that would be inconsistent with Sinegal's vision of building a long-term business. To him, treating employees well is consistent with nurturing and developing customer loyalty.

What's the Lesson Here?

In developing a strategy for your group, will you always follow the crowd? As a leader, what type of learning do you promote, and how would you design it into your operations?

The simple design is a configuration involving one or two ways of specializing individuals and units. Vertical specialization and control typically emphasize levels of supervision without elaborate formal mechanisms (for example, rule-books and policy manuals), and the majority of the control resides in the manager. Thus, the simple design tends to minimize bureaucracy and to rest more heavily on the leadership of the manager.

• Simple design is a configuration involving one or two ways of specializing individuals and units.

The simple design pattern is appropriate for many small firms, such as family businesses, retail stores, and small manufacturing firms.27 The strengths of the simple design are simplicity, flexibility, and responsiveness to the desires of a central manager—in many cases, the owner. Because a simple design relies heavily on the manager's personal leadership, however, this configuration is only as effective as is the senior manager.

One example is B&A Travel, a small travel agency owned by Helen Druse. Reporting to Helen is a part-time staff member, Jane Bloom, for accounting and finance. Jane also keeps the dedicated computer system operating. Joan Wiland heads the operations arm and supervises eight travel agents. Although each of the travel agents specializes in a geographical area, all take client requests for different types of trips. Coordination is achieved through their dedicated intranet and Internet connections. Joan uses weekly meetings and a lot of personal contact by Helen and Joan to coordinate everyone. Control is enhanced by the computerized reservation system they all use. Helen makes sure each agent has a monthly sales target and she routinely chats with important clients about their level of service. Helen realizes that developing participation from even the newest associate is an important tool in maintaining a “fun” atmosphere.

Technology and Organizational Design

LEARNING ROADMAP Operations Technology and Organizational Design / Adhocracy as a Design Option for Innovation and Learning / Information Technology and Organizational Design

Although the design for an organization should reflect its size, it must also be adjusted to fit technological opportunities and requirements.28 Successful organizations are said to arrange their internal structures to meet the dictates of their dominant “operations technologies” or workflows and, more recently, information technology opportunities.29 Operations technology is the combination of resources, knowledge, and techniques that creates a product or service output for an organization.30 Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.31

• Operations technology is the combination of resources, knowledge, and techniques that creates a product or service output for an organization.

• Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.

Operations Technology and Organizational Design

As researchers in OB have charted the links between operations technology and organizational design, two common classifications for operations technology have received considerable attention: Thompson's and Woodward's classifications.

Thompson's View of Technology James D. Thompson classified technologies based on the degree to which the technology could be specified and the degree of interdependence among the work activities with categories called intensive, mediating, and long-linked.32 Under intensive technology, there is uncertainty as to how to produce desired outcomes. A group of specialists must be brought together interactively to use a variety of techniques to solve problems. Examples are found in a hospital emergency room or a research and development laboratory. Coordination and knowledge exchange are of critical importance with this kind of technology.

Mediating technology links parties that want to become interdependent. For example, banks link creditors and depositors and store money and information to facilitate such exchanges. Whereas all depositors and creditors are indirectly interdependent, the reliance is pooled through the bank. The degree of coordination among the individual tasks with pooled technology is substantially reduced, and information management becomes more important than coordinated knowledge application.

Under long-linked technology, also called mass production or industrial technology, the way to produce the desired outcomes is known. The task is broken down into a number of sequential steps. A classic example is the automobile assembly line. Control is critical, and coordination is restricted to making the sequential linkages work in harmony.

Woodward's View of Technology Joan Woodward also divides technology into three categories: small-batch, mass production, and continuous-process manufacturing.33 In units of small-batch production, a variety of custom products are tailor-made to fit customer specifications, such as tailor-made suits. The machinery and equipment used are generally not very elaborate, but considerable craftsmanship is often needed. In mass production, the organization produces one or a few products through an assembly-line system. The work of one group is highly dependent on that of another, the equipment is typically sophisticated, and the workers are given very detailed instructions. Automobiles and refrigerators are produced in this way.

Organizations using continuous-process technology produce a few products using considerable automation. Classic examples are automated chemical plants and oil refineries.

From her studies, Woodward concluded that the combination of structure and technology was critical to the success of the organizations. When technology and organizational design were matched properly, a firm was more successful. Specifically, successful small-batch and continuous-process plants had flexible structures with small workgroups at the bottom; more rigidly structured plants were less successful. In contrast, successful mass-production operations were rigidly structured and had large workgroups at the bottom. Since Woodward's studies, various other investigations have supported this technological imperative. Today we recognize that operations technology is just one factor involved in the success of an organization.34

Adhocracy as a Design Option for Innovation and Learning

The influence of operations technology is clearly seen in small organizations and in specific departments within large firms. In some instances, managers and employees simply do not know the appropriate way to service a client or to produce a particular product. This is an extreme example of Thompson's intensive type of technology, and it may be found in some small-batch processes where a team of individuals must develop a unique product for a particular client.

• Adhocracy emphasizes shared, decentralized decision making; extreme horizontal specialization; few levels of management; the virtual absence of formal controls; and few rules, policies, and procedures.

Mintzberg suggests that at these technological extremes, the “adhocracy” may be an appropriate design.35 An adhocracy is characterized by

- Few rules, policies, and procedures

- Substantial decentralization

- Shared decision making among members

- Extreme horizontal specialization (as each member of the unit may be a distinct specialist)

- Few levels of management

- Virtually no formal controls

This design emphasizes innovation and learning. The adhocracy is particularly useful when an aspect of the firm's operations technology presents two sticky problems:

- The tasks facing the firm vary considerably and provide many exceptions, as in a management consulting firm. Or

- Problems are difficult to define and resolve.36

The adhocracy places a premium on professionalism and coordination in problem solving.37 Large firms may use temporary task forces, form special committees, and even contract with consulting firms to provide the creative problem identification and problem solving that the adhocracy promotes. For instance, Microsoft creates autonomous departments to encourage talented employees to develop new software programs. Allied Chemical and 3M set up quasi-autonomous groups to work through new ideas.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

ADHOCRACY AN D THE EX

Organizational design is often dictated by a company's business. When the business environment is fluid because of rapid changes in the marketplace, organizational designs have to be equally flexible. One extreme form is the adhocracy, where strict centralized hierarchical structure is replaced by one that relies more on groups made up of highly specialized individuals.

Out of work, Tom Reilly (Zach Braff) lands a job at Sunburst with the help of his father-in-law. Tom is in for a bit of a rude awakening. Sunburst is unlike anything from his previous professional experience. He arrives his first day to find an open-air office with employees singing, riding motorized skateboard scooters, and casually dressed. New co-workers arrive with the imaginary “yes” ball, which is designed to encourage cooperation and positive thinking. Later in the afternoon, everyone in the workgroup meets to discuss ideas and welcome Tom. When Tom unintentionally offends a co-worker, he learns about the practice of “mushiwaki,” where employees accept responsibility for their actions without having to publicly apologize.

Although the scene is meant to be comical, it does reflect a trend in newer businesses toward more open designs that give employees incredible freedom and control. Decisions are usually made in groups, so there is a high degree of interaction across functions. Professionalism and personal responsibility take the place of rules and procedures.

Get to Know Yourself Better Perhaps your instructor had you complete Exercise 34, Entering the Unknown, in the OB Skills Workbook. If not, take a moment to examine it. The exercise is designed to explore how individuals interact when they are new to a group, but it can be just as applicable to joining new organizations. You will soon be transitioning from a very structured world (i.e., school) to one that may be much looser. Expectations in this new environment may be even higher than before. How will you adjust and perform, particularly if you are not accustomed to the freedom?

We should note, however, that the adhocracy is notoriously inefficient. Many managers are reluctant to adopt this form because they appear to lose control of day-to-day operations. The implicit strategy consistent with the adhocracy is a stress on quality and individual service as opposed to efficiency. With more advanced information technology, firms are beginning to combine an adhocracy with bureaucratic elements based on advanced information systems.

Information Technology and Organizational Design

Recall that we defined information technology as the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information.38 Information technology (IT), the Web, and the computer are virtually inseparable, and they have fundamentally changed the organization design of firms to capture new competencies.39 While some suggest that IT refers only to computer-based systems used in the management of the enterprise, we take a broader view. With substantial collateral advances in telecommunication options, advances in the computer as a machine are much less profound than those information technology changes affecting how firms manage all of their parts.

From an organizational standpoint, IT can be used, among other things, as a partial substitute for some operations as well as some process controls and impersonal methods of coordination. IT has a strategic capability as well as a capability for transforming information into knowledge. For instance, most financial firms could not exist without IT because it is now the base for the industry. Financial institutions created completely new aspects of their industry based on IT, such as exotic derivatives; it is now painfully obvious that these new aspects of the industry have outpaced the ability of management to control them. Information technology, just as operations technology, can yield great good or great harm.

IT as a Substitute Old bureaucracies prospered and dominated other firms in part because they provided efficient production through specialization and through the way they managed their information. Old bureaucracies programmed jobs through rules, policies, and procedures, as well as other process controls.40 In many organizations, the initial implementation of IT displaced the most routine, highly specified, and repetitious jobs where they were highly programmed.41 A second wave of substitution replaced process controls and informal coordination mechanisms. For instance, if you apply for a credit card, a computer program, not a person, will check your credit history and other financial information. If your application passes several preset tests, you are issued a credit card.

IT to Add Capability IT has also long been recognized for its potential to add capability.42 Married to machines, IT became advanced manufacturing technology when computer-aided design (CAD) was combined with computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) to yield the automated manufacturing cell. More complex decision-support systems have provided middle and lower-level managers with programs to aid in analyzing complex problems rather than merely ratifying routine choices. IT systems can also empower individuals, expanding their jobs and making them both interesting and challenging. The emphasis on narrowly defined jobs replete with process controls imposed by middle management can be transformed to broadly envisioned, interesting jobs based on IT-embedded processes with output controls. The IT system can handle the routine operations while individuals deep within the organization deal with the exceptions.

Amazon's Expansion Means More Than Just Books

Amazon.com was founded by Jeff Bezos in 1995 with the intention of selling books directly to customers via the Internet. It has rapidly expanded into a virtual general store. With sales over $24 billion and over 24,000 employees, Amazon.com has one of the best-recognized Web site addresses and is the hub of a virtual network of organizations.

The Virtual Organization and IT Opportunities Shortly before the turn of the last century, e-business exploded upon the scene.43 Today e-business is integrated into the virtual organization, just as on-site project teams morphed into virtual project teams.

Whether it is business to business (B2B) or business to consumers (B2C), a whole new set of firms have evolved with information technology at the core of their operations. One of the more flamboyant early entrants to the B2C world is Amazon.com.

It is interesting to examine the transformation in the design of this firm to illustrate the notion of co-evolution and the ability to learn with advanced IT. Initially when Amazon just sold books, it was organized as a simple structure. As it grew, it became more complex by adding divisions devoted to each of its separate product areas. To remain flexible and promote growth in both the volume of operations and the capabilities of employees, it did not develop an extensive bureaucracy. There are still very few levels of management. It built separate organizational components based on product categories (divisional structure) with minimal rules, policies, and procedures. In other words, the organizational design it adopted appeared to be relatively conventional.44

What was not conventional was the use of IT for learning about customers and for coordinating and tracking operations and the development of extensive partnerships via IT. In comparison to Amazon.com, many other new dot-com firms adopted a variation of the adhocracy as their design pattern. The thinking was that e-business was fundamentally different from the old bricks-and-mortar operations. The managers of these firms forgot two important liabilities of the adhocracy as they grew. First, there are limits on the size of an effective adhocracy. Second, the actual delivery of their products and services did not require continual product innovation but rested more firmly on responsiveness to clients and maintaining efficiency.

The Virtual Organization As IT has become widespread, firms are finding that it can be the basis for a new way to compete. Some executives have started to develop “virtual organizations.”45 A virtual organization is an ever-shifting constellation of firms, with a lead corporation, that pools skills, resources, and experiences to thrive jointly. This ever-changing collection most likely has a relatively stable group of actors (usually independent firms) that normally includes customers, research centers, suppliers, and distributors all connected to each other. The lead firm possesses a critical competence that all need and therefore directs the constellation. While this critical competence may be a key operations technology or access to customers, it always includes IT as a base for connecting the firms.

• A virtual organization is an ever-shifting constellation of firms, with a lead corporation, that pools skills, resources, and experiences to thrive jointly.

The virtual organization works if it operates by some unique rules and is led in a most untypical way. First, the production system that yields the products and services needs to be a partner network among independent firms where they are bound together by mutual trust and collective survival. As customers desire change, the proportion of work done by any member firm might also change and the membership itself may change. In a similar fashion, the introduction of a new operations technology could shift the proportion of work among members or call for the introduction of new members. Second, this partner network needs to develop and maintain (1) an advanced information technology (rather than just face-to-face interaction), (2) trust and cross-owning of problems and solutions, and (3) a common shared culture.

The virtual organization can be highly resilient, extremely competent, innovative, and reasonably efficient—characteristics that are usually tradeoffs. Executives in the lead firm need to have the vision to see how the network of participants will both effectively compete with consistent enough patterns to be recognizable and still rapidly adjust to technological and environmental changes.46

What to Do When You Are Managing a “Virtual” Project.

- Establish a set of mutually reinforcing motives for participation, including a share in success.

- Stress self-governance and make sure there are a manageable number of high-quality contributors.

- Outline a set of rules that members can adapt to their individual needs.

- Encourage joint monitoring and sanctions of member behavior.

- Stress shared values, norms, and behavior.

- Develop effective work structures and processes via project management software.

- Emphasize the use of technology for communication and norms about how to use it.

Virtual Projects More than likely, someday you will be involved with a “virtual” network of task forces and temporary teams to both define and solve problems. Here the members will only connect electronically. Recent work on participants of the virtual teams suggests you will need to rethink what it means to “manage.” Instead of telling others what to do, you will need to treat your colleagues as unpaid volunteers who expect to participate in governing the meetings and who are tied to the effort only by a commitment to identify and solve problems.47

Environment and Organizational Design

LEARNING ROADMAP Environmental Complexity / Using Networks and Alliances

An effective organizational design also reflects powerful external forces as well as size and technological factors. Organizations, as open systems, need to receive input from the environment and in turn to sell output to their environment. Therefore, understanding the environment is important.48

The general environment is the set of cultural, economic, legal-political, and educational conditions found in the areas in which the organization operates. Firms expanding globally encounter multiple general environments. At one time, firms could separate foreign and domestic operations into almost distinct operating entities, but this is rarely the case now.

• The general environment is the set of cultural, economic, legal-political, and educational conditions found in the areas in which the organization operates.

The owners, suppliers, distributors, government agencies, and competitors with which an organization must interact to grow and survive constitute its specific environment. A firm typically has much more choice in the composition of its specific environment than its general environment. Although it is often convenient to separate the general and specific environmental influences on the firm, managers need to recognize the combined impact of both

• The specific environment is the set of owners, suppliers, distributors, government agencies, and competitors with which an organization must interact to grow and survive.

Environmental Complexity

A basic concern to address when analyzing the environment of the organization is its complexity. A more complex environment provides an organization with more opportunities and more problems. Environmental complexity refers to the magnitude of the problems and opportunities in the organization's environment, as evidenced by three main factors: the degree of richness, the degree of interdependence, and the degree of uncertainty stemming from both the general and the specific environment.

• Environmental complexity is the magnitude of the problems and opportunities in the organization's environment as evidenced by the degree of richness, interdependence, and uncertainty.

Environmental Richness Overall, the environment is richer when the economy is growing, when individuals are improving their education, and when everyone that the organization relies upon is prospering. For businesses, a richer environment means that economic conditions are improving, customers are spending more money, and suppliers (especially banks) are willing to invest in the organization's future. In a rich environment, more organizations survive, even if they have poorly functioning organizational designs. A richer environment is also filled with more opportunities and dynamism—the potential for change. The organizational design must allow the company to recognize these opportunities and capitalize on them. The opposite of richness is decline. For business firms, the current general recession is a good example of a leaner environment.

Environmental Interdependence The link between external interdependence and organizational design is often subtle and indirect. The organization may co-opt powerful outsiders by including them. For instance, many large corporations have financial representatives from banks and insurance companies on their boards of directors. One example is Fab India, a premium brand of hand-woven products that encourages its 20,000 plus artisan workers to become stockholders.

Fab India Artists Are Its Most Important Shareholders

A premium retail brand in India, Fab India sells hand-woven products produced by artisan workers. It also invites them to become shareholders and sets up centers to specialize in each region's special crafts. CEO William Bissell says: “We're somewhere between the 17th century, with our artisan suppliers, and the 21st century with our consumers.”

The organization may also adjust its overall design strategy to absorb or buffer the demands of a more powerful external element. Perhaps the most common adjustment is the development of a centralized staff department to handle an important external group. Few large U.S. corporations lack some type of centralized governmental relations group, for example. Where service to a few large customers is critical, the organization's departmentation is likely to switch from a functional to a divisionalized form.49

Uncertainty and Volatility Environmental uncertainty and volatility can be particularly damaging to large bureaucracies. In times of change, investments quickly become outmoded, and internal operations no longer work as expected. The obvious organizational design response to uncertainty and volatility is to opt for a more flexible organic form. At the extremes, movement toward an adhocracy may be important. However, these pressures may run counter to those that come from large size and operations technology. In these cases, it may be too hard or too time consuming for some organizations to make the design adjustments. Thus, the organization may continue to struggle while adjusting its design just a little bit at a time. Some firms can deal with the conflicting demands from environmental change and need for internal stability by developing alliances.

Using Networks and Alliances

In today's complex global economy, organizational design must go beyond the traditional boundaries of the firm.50 Firms must learn to co-evolve by altering their environment. Two ways are becoming more popular: (1) the management of networks and (2) the development of alliances. Many North American firms are learning from their European and Japanese counterparts to develop networks of linkages to the key firms they rely on. In Europe, for example, one finds informal combines or cartels. Here, competitors work cooperatively to share the market in order to decrease uncertainty and improve favorability for all. Except in rare cases, these arrangements are often illegal in the United States.

In Japan, the network of relationships among well-established firms in many industries is called a keiretsu. There are two common forms. The first is a bank-centered keiretsu in which firms link to one another directly through cross-ownership and historical ties to one bank. The Mitsubishi group is a good example of a company that grew through cross-ownership. In the second type, a vertical keiretsu, a key manufacturer is at the hub of a network of supplier firms or distributor firms. The manufacturer typically has both long-term supply contracts with members and cross-ownership ties. These arrangements help isolate Japanese firms from stockholders and provide a mechanism for sharing and developing technology. Toyota is an example of a firm at the center of a vertical keiretsu.

A specialized form of network organization is evolving in U.S.-based firms as well. Here, the central firm specializes in core activities, such as design, assembly, and marketing, and works with a small number of participating suppliers on a long-term basis for both component development and manufacturing efficiency. The central firm is the hub of a network where others need it more than it needs any other member. Although Nike was a leader in the development of these relationships, now it is difficult to find a large U.S. firm that does not outsource extensively.

Another option is to develop interfirm alliances, which are cooperative agreements or joint ventures between two independent firms.51 Often, these agreements involve corporations that are headquartered in different nations. In hightech areas, such as robotics, semiconductors, advanced materials (ceramics and carbon fibers), and advanced information systems, a single company often does not have all of the knowledge necessary to bring new products to the market. Alliances are quite common in such high-technology industries. Through their international alliances, high-tech firms seek to develop technology and to ensure that their solutions standardize across regions of the world.

• Interfirm alliances are announced cooperative agreements or joint ventures between two independent firms.

Developing and effectively managing an alliance is a managerial challenge of the first order. Firms are asked to cooperate rather than compete. The alliance's sponsors normally have different and unique strategies, cultures, and desires for the alliance itself. Both the alliance managers and sponsoring executives must be patient, flexible, and creative in pursuing the goals of the alliance and each sponsor. It is little wonder that some alliances are terminated prematurely.52

Of course, alliances are but one way of altering the environment. The firm can also invest in the projects of other firms through corporate venture capital. It may acquire other companies to bring their expertise directly into the firm. All of these can be beneficial.53 However, these initiatives need to be related to the strategy of the firm and its technology. And all of these alert us to the fact that in addition to organizational design, strategy and learning call for leadership of the whole organization.

Strategic Leadership of the Whole Organization

LEARNING ROADMAP Strategic Leadership and the Challenges at Multiple Levels / Developing a Top-Management Team / Using Top-Management Leadership Skills

Even with an organizational design perfectly matched to the size, technology, and environment of the firm, it must still be led. Leading the whole effort is often called strategic leadership.54 When the focus is on strategic leadership, it is the study of leading a quasi-independent unit, department, or organization. Although many focus on the individual at the top of the pyramid, such as the chief executive officer or the president of the United States, research suggests that strategic leadership is not rooted in just the top-management team or the CEO.55 The top-management team as a group is also important. For example, if there is greater diversity in the challenges and opportunities facing the firm, the top-management team should be more diverse.56 So leading the whole organization calls for understanding the unique challenges facing both the individual at the top and the top-management team. Whereas the head of the organization needs to understand the challenges of the job, the top-management team needs to develop an effective group process that will cope with the struggles and opportunities facing the firm.

• Strategic leadership is leadership of a quasi-independent unit, department, or organization.

Strategic Leadership and the Challenges at Multiple Levels

Starting from the bottom, organizations can be separated into three major zones: (1) the production zone, (2) the administrative zone, and (3) the systems zone. As the names imply, the challenge to the leader across the zones vary. That is, leadership requirements at different levels or echelons of management differ.57 Each echelon gets more complex than the one beneath it in terms of its leadership and managerial requirements. Leaders at top levels have special responsibilities since their influence cascades throughout the organization.

One way of expressing the increasing complexity of the levels is in terms of how long it takes to see the results of the key decisions required at any given level. The timeframe can range from 3 months or so at the lowest level, which emphasizes hands-on work performance and practical judgment to solve ongoing problems, to 20 years or more at the top.

Because problems become increasingly complex from the lower levels to the upper levels of the organization, you can expect that managers at each level must demonstrate increasing cognitive and behavioral complexity in order to deal with an increase in organizational complexity. Cognitive complexity deals with the degree to which individuals perceive nuances and subtle differences, whereas behavioral complexity centers on the possession of a repertoire of roles and the ability to selectively apply them. In other terms cognitively complex individuals see more subtle variations, and those who are behaviorally complex can act in a wider variety of roles than those who are less complex.

• Cognitive complexity is the degree to which individuals perceive nuances and subtle differences.

• Behavioral complexity is the possession of a repertoire of roles and the ability to selectively apply them.

One way of measuring a manager's cognitive complexity is in terms of how far into the future he or she can develop a vision. Accompanying such a vision should be an increasing range and sophistication of leadership behaviors.

When there is a focus on complexity at the top, researchers often stress how strategic leadership cascades deep within the organization. One example of such cascading, indirect leadership is the leadership-at-a-distance. Even individuals several levels above a unit can influence the style and tone of what occurs in a unit. The systems zone leadership at the top of an organization is normally responsible for producing complex systems, organizing acquisition of major resources, creating vision, developing strategy and policy, and identifying organizational design. These functions call for a much broader conception of leadership. In many respects leadership of this zone combines leadership and management as choices made at the top cascade down the organization. One subtle example of cascading leadership is known as “intent of the commander” where middle-level leaders try to mimic what they think the top-level leader would do in their situation.58 Researchers have linked CEO values to culture and then to organizational outcomes as the values of the CEO cascaded down.59

Leadership of the organization also involves a face-to-face influence as well. Regardless of the level, leaders must engage in direct supervision and must be effective followers. The saying is that “everyone has a boss.” And even most CEOs would argue that those near the top must act as a team and the notion of shared leadership at the top of the organization is clearly relevant.60 The top-management team is particularly important.

Developing a Top-Management Team

Top-management teams (TMTs) refer to the relatively small group of executives at the very top of the organization or the leaders of the firm. Often the top-management team is composed of 3 to 10 executives.61 The composition of the top-management team is important because the collective nature, temperament, outlook, and interactions among these individuals alter the choices made in the leadership of the organization.

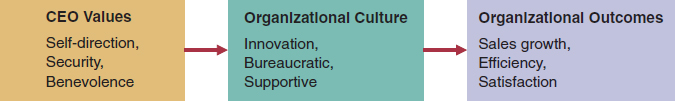

CEO Values Make a Difference

Although there has been a lot of discussion about how the values of the CEO impact performance, comparatively few comprehensive studies have been done. Recently, Y. Berson, S. Oreg, and T. Dvir started to remedy this gap with a study of CEO values, organizational culture, and performance. They suggested that individuals are drawn to and stay with organizations that have value priorities similar to their own. That includes the CEO. Furthermore, the CEO reinforces some values over others, and this has a measurable impact on the organizational culture. The organizational culture, then, emphasizes some aspects of performance over others.

The researchers hypothesized and found the following in a study of some 22 CEOs and their firms in Israel: CEOs tend to place a high priority on self-direction or security or benevolence. This priority tends to emphasize a particular type of organizational culture. Specifically, when a CEO values self-direction, there is more cultural emphasis on innovation; when a CEO values security, there is more cultural emphasis on bureaucracy; and when a CEO values benevolence, the culture is more supportive of its members. Then they linked aspects of organizational culture with specific elements of performance (organizational outcomes). More innovation was associated with higher sales growth. A bureaucratic culture was linked to efficiency, while a supportive culture was associated with greater employee satisfaction. In sum, CEO values are linked to organizational culture, which, in turn, is associated with organizational outcomes. Schematically, it looks like this:

Do the Research Do you think this study would transfer to firms located in North America? Is it possible that firms with an established innovative culture select a CEO that values self-direction?

Source: Yair Berson, Shaul Oreg, and Taly Dvir, “CEO Values, Organizational Culture and Firm Outcomes,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 29 (2008), pp. 615–633.

The composition of a top-management team can have a major influence on how an organization operates in terms of the shared culture, decision-making, and management styles, and even on the ethical foundation of day-to-day workplace behaviors.

Much of the research on top-management teams uses demographic characteristics as proxies for harder-to-obtain psychological variables. Such variables as age, tenure, education, and functional background are used in this perspective. Researchers typically attempt to link such variables to various kinds of organizational outcomes, including sales growth, innovation, and executive turnover.62

Because of conflicting findings, researchers have been working to enrich this approach. One important review argues that a given TMT is likely to face a variety of different situations over time. Demographic composition may be relatively stable, but the tasks are dynamic and variable. Sometimes team members have similar information (symmetric) and interests, and sometimes not (asymmetric). With asymmetric information and symmetric interests, there is an opportunity for the top-management team to develop new innovative solutions. For example, when considering a merger, some executives may have information on the potential partner's finances, on its management style and strategy, or on the partner's connections with others. The team may initially move to buy the new partner but sell off selected portions of the new business.

Top-Management Team Composition Influences Organization

The composition of a top-management team can have a major influence on how an organization operates in terms of a shared culture, decision making, and even the ethical foundation of day-to-day workplace behaviors.

In today's dynamic environment it is desirable for top-management teams to have a variety of skills, experiences, and emergent theories that are basically explanations of what might happen and why. Diversity of the skills and abilities of the team can promote debate and discussion, which can lead to more comprehensive, balanced, and effective initiatives for improvement.63 Homogeneous top-management groups are less likely to identify and respond to subtle but important variations. This can result in stale strategies, unresponsiveness, and dulling consistency. Of course, there are practical limits to the degree of diversity and the range of emergent theories that top-management can effectively discuss. Too much variation can yield excessive discussion and paralysis by analysis.64

The TMT researchers argue that group process must be handled differently and effectively for dynamic versus less dynamic settings. Not only should the composition of the top management team be adjusted to the degree of change facing the firm, but there should also be adjustments in group process. With change facing the firm, there needs to be more emphasis on processing information, a representation of broader interests, a strong recognition of existing power asymmetries, and additional emphasis on developing new emergent theories of action.65

Using Top-Management Leadership Skills

So far we have suggested that the challenges at the top are unique, that leaders need to be cognitively complex with a far-reaching vision and possess behavioral complexity. We also noted the importance of the cascading effects of leadership at the top and the critical role of the top-management team. Now it is time to put all of this together in a model developed by Boal and Hooijberg. Their model focuses on the tensions and complexity faced by strategic leaders and is shown in Figure 17.1.66

In their model, Boal and Hooijberg express the challenges at the top in terms of tensions among desirable conditions. They describe these tensions as stemming from Emergent Theories and the Competing Values Framework (CVF).67 Specifically, tensions exist between (1) flexibility versus control and (2) internal focus versus external focus. The flexibility versus control dimension contrasts actions focused on goal clarity and efficiency and those emphasizing adaptation to people and the external environment. The internal versus external focus dimension distinguishes between social actions emphasizing such internal effectiveness measures as employee satisfaction versus a focus on external effectiveness measures such as market share and profitability.

Figure 17.1 Boal and Hooijberg Perspective on Strategic Leadership.: [Source; Kimberly B. Boal and Robert Hooijberg, “Strategic Leadership Research: Moving On.” The Leadership Quarterly 11 (2009).]

Combinations of these tensions yield a variety of potential roles that can be used in addressing these tensions. In the terms used by Boal and Hooijberg, a leadership role is a set of influence attempts crafted to meet a specific combination of challenges.68 For instance, the leader may be asked to deal with the combination of (1) the need for high flexibility coupled with high-control requirements in addition to (2) a call for high emphasis on external performance but a low requirement for internal effectiveness. This need would suggest that the leader perform one role. A different combination would ask the leader to perform a slightly different role. Although it is possible to detail the leadership roles for each possible combination, the point of our discussion is to stress the wide variety of roles the leader may need to perform. Also note that the leader needs to see the tensions in combination (the need for cognitive complexity) as well as be able to act accordingly (behavioral complexity).

Overall, executives who can display a large repertoire of leadership roles and know when to apply these roles are more likely to be effective than leaders who have a small role repertoire and who indiscriminately apply these roles. Since the challenges often shift, executives need cognitive and behavioral complexity as well as flexibility. Of course, they may understand and see the differences between their subordinates and superiors but not be able to behaviorally differentiate so as to satisfy the demands of each group. It is not always possible to successfully influence others.

Figure 17.1 shows that CVF, behavioral complexity, emotional complexity, and cognitive complexity are directly associated with absorptive capacity, capacity to change, and managerial wisdom as well as with charismatic/transformational leadership and vision. In other words, the block to the left shows the challenges and opportunities facing those at and near the top. The leadership of these individuals, both alone and in combination, alters the degree to which the firm can adjust day-to-day management. As the complexity of the challenges and opportunities increases, there is more stress on the organization. How it is led then becomes more important.

Organizational Competencies and Strategic Leadership Finally, consistent with the research of Boal and Hooijberg, it is important to recognize key organizational competencies and link them with strategic leadership effectiveness and ultimately with organizational effectiveness.69 The first key competency is absorptive capacity. Absorptive capacity is the ability to learn. It involves the capacity to recognize new information, assimilate it, and apply it to new ends. It utilizes processes necessary to improve the organization-environment fit. Absorptive capacity of strategic leaders in the top-management team is of particular importance because those in such a position have a unique ability to change or reinforce organizational action patterns.

•Absorptive capacity is the ability to learn.

The second key competency is adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity refers to the ability to change. Boal and Hooijberg argue that in the new, fast-changing competitive landscape, organizational success calls for strategic flexibility—that is, the ability to respond quickly to competitive conditions. The third key competency is managerial wisdom, which involves the ability to perceive variation in the environment and understand the social actors and their relationships. Thus, emotional intelligence is called for, and the leader must be able to take the right action at the right moment.

- Adaptive capacity refers to the ability to change.

- Managerial wisdom is the ability to perceive variations in the environment and understand the social actors and their relationships.

An Example of the Model Let's look at an integrative example of an engineering company that, at one time, had 100 percent of its contracts with the Department of Defense. Alice Smith left the meeting with the top-management team with a clear mandate—a company reorientation was necessary given a pending decline in the U.S. defense budget. The company had to reconceptualize its organizational system to ensure future profitability and continued employment for all. Contract bidding procedures changed; the company no longer needed to comply with numerous government regulations in terms of its contracts, and executive leaders had to acquire new customers. All of this called for a capacity to change, the adsorption of new skills, and the wisdom to choose a viable new path. These leaders formulated future visions and emphasized organizational transformation. They hired others to help retrain themselves and their workforce. They even appeared charismatic, if not visionary, as they pushed the pace of change. As strategic leaders high in behavioral complexity and emotional intelligence, they spotted new consumer trends for variations of existing products and moved quickly to capture new markets even as they phased out their old contracts.70 Some two years after their fateful meeting, the firm was in the middle of a fundamental transition. The future looked bright, and before long it would be time to plan for another change.

17 study guide

Key Questions

Why are strategy and organizational learning important?

- Strategy is the process of positioning the organization in the competitive environment and implementing actions to compete successfully. It is a pattern in a stream of decisions.

- Organizational learning is the process of acquiring knowledge and using information to adapt successfully to changing circumstances.

- For organizations to learn, they must engage in knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention in adapting successfully to changing circumstances.

- Firms use mimicry, experience, vicarious learning, scanning, and grafting to acquire information.

- Firms establish mechanisms to convert information into knowledge. Chief among the problems of interpretation are self-serving interpretations.

- Firms retain information through individuals, transformation mechanisms, formal structure, physical structure, external archives, and their IT system.

- To compete successfully, individuals, units, and firms will need to constantly learn because of changes in the scope of operations, technology, and the environment.

What is organizational design, and how is it linked to strategy?

- Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration for an organization.

- Organizational design is a way to implement the positioning of the firm in its environment.

- Organizational design provides a basis for a consistent stream of decisions.

- Strategy and organizational design are interrelated and must evolve with changes in size, technology, and the environment.

- The design of a large organization is far more complex than that of a small firm.

- With aging, firms become subject to routine managerial scripts. Large organizations will need to systematically break down boundaries limiting learning.

- Smaller firms often adopt a simple structure because it works, is cheap, and stresses the influence of the leader.

How does technology influence organizational design?

- Operations technology and organizational design should be interrelated to ensure the firm produces the desired goods and/or services.

- Adhocracy is an organizational design used in technology-intense settings.

- Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.

- IT provides an opportunity to change the design by substitution, for learning, and to capture strategic advantages.

- IT forms the basis for the virtual organization.

How does the environment influence organizational design?