Chapter 2

Creating Your First Drawing

This chapter examines some of AutoCAD’s basic functions. You’ll get a chance to practice with the drawing editor by building a simple drawing to use in later exercises. You’ll learn how to give input to AutoCAD, interpret prompts, and get help when you need it. This chapter also covers the use of coordinate systems to give AutoCAD exact measurements for objects. You’ll see how to select objects you’ve drawn and how to specify base points for moving and copying.

If you’re not a beginning AutoCAD user, you may want to move on to the more complex material in Chapter 3, “Setting Up and Using AutoCAD’s Drafting Tools.” You can use the files supplied on the companion website, www.sybex.com/go/masteringautocadmac, to continue the tutorials at that point.

In this chapter, you’ll learn to do the following:

- Specify distances with coordinates

- Interpret the cursor modes and understand prompts

- Select objects and edit with grips

- Use dynamic input

- Get help

- Display data in the Command Line palette

- Display the properties of an object

Getting to Know the Tool Sets palette

Your first task in learning how to draw in AutoCAD is simply to draw a line. Since AutoCAD is designed as a precision drawing tool, you’ll be introduced to methods that allow you to input exact distances. But before you begin drawing, take a moment to familiarize yourself with the feature you’ll be using more than any others to create objects with AutoCAD: the Tool Sets palette.

1. Start AutoCAD just as you did in Chapter 1, “Exploring the AutoCAD Interface,” by clicking the AutoCAD icon in the Dock.

2. Make sure that the Tool Sets palette is displaying the drafting tools. To do this, click the icon in the Tool Sets palette title bar and select Drafting (Figure 2-1).

3. Move the arrow cursor to the Line tool in the Tool Sets palette. As you hold the cursor over the tool, a tooltip appears (see Figure 2-2).

Figure 2-1:The Tool Sets palette title bar menu

Figure 2-2:The tools you’ll use in this chapter and the Line tool and tooltip

4. Slowly move the arrow cursor to the right over the other tools in the Tool Sets palette and read each tooltip.

In most cases, you’ll be able to guess what each tool does by how it looks. The tooltips will help you identify any tools that you’re not sure of. You can use Figure 2-2 to find the tools for the exercises in this chapter.

In Chapter 1, you looked at a preexisting sample drawing. This time, you’ll begin to draw your own drawing by creating a door that will be used in later exercises. First, though, you must learn how to tell AutoCAD what you want, and even more important, you must understand what AutoCAD wants from you.

Imperial and Metric

In this chapter, you’ll start to see instructions for both Imperial and metric measurements. In general, you’ll see the instructions for Imperial measurement first, followed by the metric instructions. You won’t be dealing with inches or centimeters yet, however. You’re just getting to know the AutoCAD system.

You’ll start by setting the size of the work area, known as the drawing limits. These limits aren’t fixed in any way, and you aren’t forced to stay within the bounds of the drawing limits unless the Limits ON/OFF command line option is turned on. But limits can help to establish a starting area from which you can expand your drawing.

AutoCAD starts with a new blank file, but it’s a little difficult to tell how big the drawing area is. First, you’ll set up the work area so you have a better idea of the space you’re working with:

1. Choose Format Drawing Limits from the menu bar.

2. At the Specify lower left corner or prompt, right-click and select Enter. You can also press ↵ or the spacebar. By doing this, you are accepting the default location for the lower-left corner, which is the coordinate 0,0.

3. At the Specify upper right corner <12.0000,9.0000>: prompt, if you use Imperial units (feet and inches), press ↵ to accept the default of 12.0000,9.0000. Metric users should enter 40,30↵.

4. Choose View Zoom All. You can also type Z↵ A↵.

In the last step, the All option of the Zoom command uses the limits you set up in steps 2 and 3 to determine the display area. In a drawing that contains objects, the Zoom command’s All option displays the limits plus the area occupied by the objects in the drawing if they happen to fall outside the limits. Now give your file a unique name:

1. Choose File Save As from menu bar or type Saveas↵ to open the Save Drawing As dialog box.

2. Type Door. As you type, the name appears in the Save As text box.

3. Save your file in the Documents folder, or if you prefer, save it in another folder of your choosing. Just remember where you put it because you’ll use it later.

4. Click Save. You now have a file called Door.dwg, located in the Documents folder. Of course, your drawing doesn’t contain anything yet. You’ll take care of that next.

Understanding the Drawing Area

The new file shows a drawing area roughly 12 inches wide by 9 inches high. Metric users have a file that shows an area roughly 40 mm wide by 30 mm high. This is just the area you’re given to start with, but you’re not limited to it in any way. No visual clues indicate the size of the area. To check the area size for yourself, turn on the Dynamic Input display and then choose Tools Inquiry ID Point. Move the crosshair cursor to the upper-right corner of the drawing area and observe the value in the coordinate readout at the cursor. Click the upper-right corner. The coordinate is reported in the expanded Command Line palette in X, Y, and Z coordinate values. The coordinate won’t show exactly 12 × 9 inches, or 40 × 30 mm for metric, because the proportions of your drawing area aren’t likely to be exactly 12 × 9 or 40 × 30. AutoCAD does try to optimize the display for the drawing area when you choose the All option of the Zoom command.

You’re almost ready to do some drawing. Before you begin, turn off the Dynamic Input display. The Dynamic Input display is a great tool, but while you’re learning how to enter coordinates, it can be a distraction.

1. Locate the Dynamic Input tool in the status bar and click it to turn it off. You can tell it is off when it turns a light gray color (Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-3:The Dynamic Input, Polar Tracking, and Object Snap tools

2. Locate the Polar Tracking tool in the status bar and click it to turn it on. The Polar Tracking tool should now be blue, indicating that it is on (Figure 2-3).

3. Locate the Object Snap tool in the status bar and click it to turn it off. The Object Snap tool should now be gray, indicating that it is off (Figure 2-3).

You’ll get a chance to work with the Dynamic Input display and Object Snap a bit later in this chapter. I’m asking you to turn these features off for now to simplify AutoCAD’s behavior.

Now you can begin to explore the drawing process. To begin a drawing, follow these steps:

1. Click the Line tool on the Tool Sets palette. You can also choose Draw Line from the menu bar or type L↵.

You’ve just issued the Line command. AutoCAD responds in two ways. First, you see the message

Specify first point:

in the Command prompt, asking you to select a point to begin your line. Also, the cursor changes its appearance; it no longer has a square in the crosshairs. This is a clue telling you to pick a point to start a line.

2. Using the left mouse button, select a point in the drawing area near the center. After you select the point, AutoCAD changes the prompt to this:

Specify next point or [Undo]:

Now as you move the mouse around, notice the line with one end fixed on the point you just selected and the other end following the cursor in a rubber-banding motion (see the first image in Figure 2-4).

3. Move the cursor to a location directly to the left or right of the point you clicked, and you’ll see a dotted horizontal line appear along with a message at the cursor. This action also occurs when you point directly up or down. Your cursor seems to jump to a horizontal or vertical position (Figure 2-5).

Figure 2-4:While drawing line segments, a rubber-banding line follows the cursor.

Figure 2-5:Polar Tracking

This feature is called Polar Tracking, and you turned it on at the beginning of this section. Like a T-square or triangle, it helps to restrict your line to an exact horizontal or vertical direction. You can turn Polar Tracking on or off by clicking the Polar Tracking tool in the status bar. You’ll learn more about Polar Tracking in Chapter 3.

4. Continue with the Line command. Move the cursor to a point below and to the right of the first point you selected, and click again. You’ve just drawn a line segment, and a second rubber-banding line appears (see the second image in Figure 2-4).

5. If the line you drew isn’t the exact length you want, you can back up during the Line command and change it. To do this, right-click and select Undo or type U↵. The line you drew previously rubber-bands as if you hadn’t selected the second point to fix its length.

6. Right-click and select Enter. This terminates the Line command.

You’ve just drawn and then undrawn a line of an arbitrary length. The Line command is still active. Two onscreen clues tell you that you’re in the middle of a command. If you don’t see the word Command to the left of the Command Line input area, a command is still active. Also, the cursor is the plain crosshair without the box at its intersection.

From now on, I’ll refer to the crosshair cursor without the small box as the Point Selection mode of the cursor. If you look ahead to Figure 2-11, you’ll see all the modes of the drawing cursor.

Keyboard Aliases and the Spacebar

Throughout this book, you are shown the keyboard alias for commands. Long-time AutoCAD users swear by them, and even new users find they prefer command aliases over the menu bar or tools. And if you are a long-time Mac user, you know how useful keyboard shortcuts can be in a variety of situations. But if it seems awkward to hit the ↵ key to start a command, you have an alternative: Just press the spacebar. That way, you can keep one hand on the mouse while entering keyboard aliases. So whenever you see ↵, think “spacebar” instead of the Return key.

Specifying Exact Distances with Coordinates

Next, you’ll continue with the Line command to draw a plan view (an overhead view) of a door, to no particular scale. This will give you some practice in drawing objects to exact distances. Later, you’ll resize the drawing to use in future exercises. The door will be 3.0 units long and 0.15 units thick. For metric users, the door will be 9 units long and 0.5 units thick. To specify these exact distances in AutoCAD, you can use either relative polar coordinates or Cartesian coordinates.

The Imperial and metric distances aren’t equivalent in the exercises in this chapter. For example, 3 units in the Imperial-based drawing aren’t equal to 9 metric units. These distances are arbitrary and based on how they appear in the figures in this chapter.

Getting Out of Trouble

Beginners and experts alike are bound to make a few mistakes. Before you get too far into the tutorial, here are some powerful but easy-to-use tools to help you recover from accidents:

Delete If you make a typing error, press the Delete key to back up to your error, and then retype your command or response. You can also use the Delete key to delete objects in your drawing. Just select an object or set of objects and press Delete. The Delete key is in the upper-right corner of the main keyboard area.

Escape (Esc) This is perhaps the single most important key on your keyboard. When you need to exit a command or a dialog box quickly without making changes, press the Esc key in the upper-left corner of your keyboard. In most cases, you need to press Esc only once, although it won’t hurt to press it twice. (Press Esc before editing with grips or issuing commands through the keyboard.)

Cancel Another way to quit out of a command is to right-click and select Cancel from the shortcut menu. This works just like the Esc key.

F-Z and U↵ If you accidentally change something in the drawing and want to reverse that change, you can use the standard F-Z keystroke to back up one operation. You can also type U↵ at the Command prompt. Each time you do this, AutoCAD undoes one operation at a time, in reverse order. The last command performed is undone first, then the next-to-last command, and so on. The prompt displays the name of the command being undone, and the drawing reverts to its state prior to when that command was issued. If you need to, you can undo everything back to the beginning of an editing session.

Undo If you want more control over the way Undo works, you can use the Undo command, which allows you to “bookmark” places in your editing session that you can “undo” to. Type Undo↵ and you’ll see the Enter the number of operations to undo or [Auto/Control/BEgin/End/Mark/Back] <1>: prompt. You can enter a number indicating the number of steps you want to “undo.” Use the Mark option to “bookmark” a location; then use Back to undo your work to that “bookmark.” You can use Begin and End to mark the beginning and end of a set of operations that will be undone all at once. Control offers options to control the behavior of the Undo command. Auto is an option that is on by default and causes AutoCAD to undo the action of the whole command rather than the individual actions within a command.

Redo If you accidentally undo one too many commands, you can redo the last undone command by pressing F-Y or by typing Redo↵.

Palette toggle If a palette has been turned off, you can turn it back on by choosing Tools Palettes. A list of palettes appears. Click the palette that you want to turn on.

Specifying Polar Coordinates

To enter the exact distance of 3 (or 9 metric) units to the right of the last point you selected, do the following:

1. Click the Line tool in the Tool Sets palette, or type L↵.

2. Click a point slightly to the left of the center of the drawing area to select the start point.

3. Type @3<0. Metric users should type @9<0. As you type, the letters appear at the Command prompt.

4. Press ↵. A line appears, starting from the first point you picked and ending 3 units to the right of it (see Figure 2-6). You’ve just entered a relative polar coordinate.

The “at” sign (@) you entered tells AutoCAD that the coordinate you’re specifying is from the last point you selected. The 3 (or 9 metric) is the distance, and the less-than symbol (<) tells AutoCAD that you’re designating the angle at which the line is to be drawn. The last part is the value for the angle, which in this case is 0 for 0°. This is how to use polar coordinates to communicate distances and directions to AutoCAD.

If you’re accustomed to a different method for describing directions, you can set AutoCAD to use a vertical direction or downward direction as 0°. See Chapter 3 for details.

Angles are given based on the system shown in Figure 2-7, in which 0° is a horizontal direction from left to right, 90° is straight up, 180° is horizontal from right to left, and so on. You can specify degrees, minutes, and seconds of arc if you want to be that exact. I’ll discuss angle formats in more detail in Chapter 3.

Figure 2-6:Notice that the rubber-banding line now starts from the last point selected. This indicates that you can continue to add more line segments.

Figure 2-7:AutoCAD’s default system for specifying angles

Specifying Relative Cartesian Coordinates

For the next line segment, let’s try another method for specifying exact distances:

1. Enter @0,0.15↵. Metric users should enter @0,0.5↵. A short line appears above the endpoint of the last line. Once again, @ tells AutoCAD that the coordinate you specify is from the last point picked. But in this example, you give the distance in X and Y values. The X distance, 0, is given first, followed by a comma, and then the Y distance, 0.15. This is how to specify distances in relative Cartesian coordinates.

Commas and Periods

Step 1 indicates that metric users should enter @0,0.5↵ for the distance. Instead, you could enter @0,.5 (zero comma point five). The leading zero is included for clarity. Please be aware that the comma is used as a separator between the X and Y components of the coordinate. In AutoCAD, commas aren’t used for decimal points; you must use a period to denote a decimal point.

2. Enter @-3,0↵. Metric users should enter @-9,0↵. This distance is also in X,Y values, but here you use a negative value to specify the X distance. The result is a drawing that looks like Figure 2-8.

Figure 2-8:These three sides of the door were drawn by using the Line tool. Points are specified by using either relative Cartesian or polar coordinates.

Positive values in the Cartesian coordinate system are from left to right and from bottom to top (see Figure 2-9). (You may remember this from your high school geometry class!) If you want to draw a line from right to left, you must designate a negative value. It’s also helpful to know where the origin of the drawing lies. In a new drawing, the origin—or coordinate 0,0—is in the lower-left corner of the drawing.

Figure 2-9:Positive and negative Cartesian coordinate directions

3. Type C↵. This C stands for the Close option. It closes a sequence of line segments. A line connecting the first and last points of a sequence of lines is drawn (see Figure 2-10), and the Line command terminates. The rubber-banding line also disappears, telling you that AutoCAD has finished drawing line segments. You can also use the rubber-banding line to indicate direction while simultaneously entering the distance through the keyboard. See the sidebar “Other Ways to Enter Distances.”

To finish drawing a series of lines without closing them, you can press Esc, ↵, or the spacebar.

Figure 2-10:Distance and direction input for the door. Distances for metric users are shown in brackets.

Interpreting the Cursor Modes and Understanding Prompts

The key to working with AutoCAD successfully is understanding the way it interacts with you. The following sections will help you become familiar with some of the ways AutoCAD prompts you for input. Understanding the format of the messages in the Command Line palette and recognizing other events on the screen will help you learn the program more easily.

Understanding Cursor Modes

As the Command Line palette aids you with messages, the cursor gives you clues about what to do. Figure 2-11 illustrates the various modes of the cursor and gives a brief description of the role of each mode. Take a moment to study this figure.

Figure 2-11:The drawing cursor’s modes

The Standard cursor tells you that AutoCAD is waiting for instructions. You can also edit objects by using grips when you see this cursor. Grips are squares, rectangles, or arrowheads that appear at endpoints and at the midpoint of objects when they’re selected. (You might know them as workpoints from other graphics programs.)

Other Ways to Enter Distances

A third method for entering distances is to point in a direction with a rubber-banding line and then enter the distance through the keyboard. For example, to draw a line 3 units long from left to right, click the Line tool in the Tool Sets palette, click a start point, and then move the cursor so the rubber-banding line points to the right at some arbitrary distance. With the cursor pointing in the direction you want, type 3↵. The rubber-banding line becomes a fixed line 3 units long. Using this method, called the Direct Distance method, along with the Ortho mode or Polar Tracking described in Chapter 3, can be a fast way to draw orthogonal lines of specific lengths.

If you turn on Dynamic Input, you can also specify an exact angle along with the distance. For example, start the Line command and then pick the first point. Type 3 for the length but don’t press ↵. Press the Tab key instead. The line segment will become fixed at 3 units, and as you move the cursor, the segment will rotate freely around the first point. Next type an angle in degrees, 30↵ for example, and the line will be drawn at 30 degrees. Or, instead of typing in an angle, just adjust the angle of the line visually until you see the angle you want on the Dynamic Input temporary angle dimension, and then click the mouse.

If you watch the temporary dimensions as you press the Tab key, you’ll see that the Tab key lets you move from the length dimension to the angle dimension and back again. You can press the Tab key at any time to shift back and forth between dimensions. A lock appears next to a dimension that you have entered, telling you that the dimension is “locked” until you tab to it again.

You’ll learn more about how to enter values with the Dynamic Input’s temporary dimensions later in this chapter.

The Point Selection cursor appears whenever AutoCAD expects point input. It can also appear in conjunction with a rubber-banding line. You can either click a point or enter a coordinate through the keyboard.

The Object Selection cursor tells you that you must select objects—either by clicking them or by using any of the object-selection options available.

The Osnap (object snap) marker appears along with the Point Selection cursor when you invoke an osnap. Osnaps let you accurately select specific points on an object, such as endpoints or midpoints.

The tracking vector appears when you use the Polar Tracking or Object Snap Tracking feature. Polar Tracking aids you in drawing orthogonal lines, and Object Snap Tracking helps you align a point in space relative to the geometry of existing objects. Object Snap Tracking works in conjunction with osnaps. You’ll learn more about the tracking vector in Chapters 3 and 4.

If you’re an experienced AutoCAD user, you may prefer to use the old-style crosshair cursor that crosses the entire screen. You can change the size of the crosshair cursor through the Cursor And Selection settings in the Application Preferences dialog box. See Appendix B on the companion website for more on the Preferences settings.

Choosing Command Options

Many commands in AutoCAD offer several options, which are often presented to you in the Command window in the form of a prompt. This section uses the Arc command to illustrate the format of AutoCAD’s prompts.

Usually, in a floor-plan drawing in the United States, an arc is drawn to indicate the direction of a door swing. Figure 2-12 shows a drawing that includes other standard symbols used in architectural-style drawings.

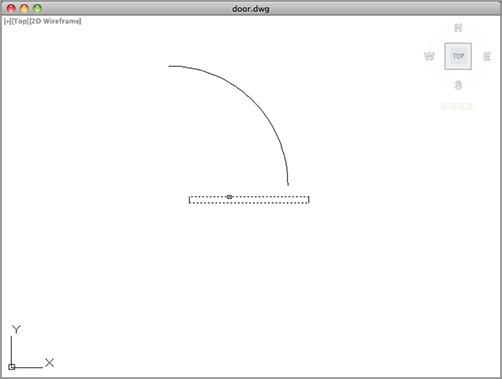

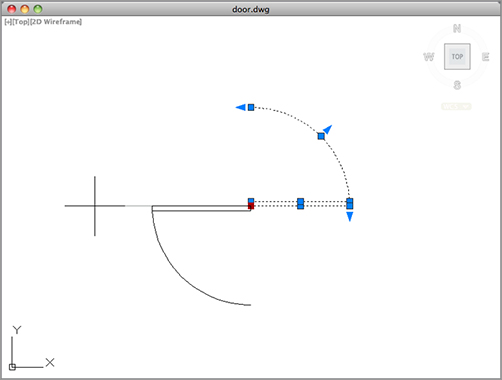

Here, you’ll draw the arc for the door you started in the previous exercise:

1. Click the 3-Point Arc tool in the Tool Sets palette. The Specify start point of arc or [Center]: prompt appears, and the cursor changes to Point Selection mode.

Examine the Specify start point of arc or [Center]: prompt in the Command Line palette. The start point contains two options. The default option is the one stated in the main part of the prompt. In this case, the default option is to specify the start point of the arc. If other options are available, they appear within square brackets. In the Arc command, you see the word Center within brackets telling you that, if you prefer, you can also start your arc by selecting a center point instead of a start point. If multiple options are available, they appear within the brackets and are separated by slashes (/). The default is the option AutoCAD assumes you intend to use unless you tell it otherwise.

2. Type C↵ to select the Center option. The Specify center point of arc: prompt appears. Notice that you had to type only the C and not the entire word Center.

When you see a set of options in the Command Line palette, note their capitalization. If you choose to respond to prompts by using the keyboard, these capitalized letters are all you need to enter to select the option. In some cases, the first two letters are capitalized to differentiate two options that begin with the same letter, such as LAyer and LType.

Figure 2-12:Samples of standard symbols used in architectural drawings

3. Pick a point representing the center of the arc near, but not too close to, the upper-left corner of the door (see the top image in Figure 2-13). The Specify start point of arc: prompt appears.

4. Type @3<0↵. Metric users should type @9<0↵. The Specify end point of arc or [Angle/chord Length]: prompt appears.

5. Move the mouse and a temporary arc appears, originating from a point 3 units to the right of the center point you selected and rotating about that center, as in the middle image in Figure 2-13. (Metric users will see the temporary arc originating 9 units to the right of the center point.)

As the prompt indicates, you now have three options. You can enter an angle, a chord length, or the endpoint of the arc. The prompt default, to specify the endpoint of the arc, picks the arc’s endpoint. Again, the cursor is in Point Selection mode, telling you it’s waiting for point input. To select this default option, you only need to pick a point on the screen indicating where you want the endpoint.

6. Move the cursor so that it points in a vertical direction from the center of the arc. You’ll see the Polar Tracking vector snap to a vertical position (Figure 2-14).

7. Click any location with the Polar Tracking vector in the vertical position. The arc is now fixed in place, as in the bottom image of Figure 2-13.

Figure 2-13:Using the Arc command

Figure 2-14:The vertical Polar Tracking vector

This exercise has given you some practice working with AutoCAD’s Command Line palette prompts and entering keyboard commands—skills you’ll need when you start to use some of the more advanced AutoCAD functions.

As you can see, AutoCAD has a distinct structure in its prompt messages. You first issue a command, which in turn offers options in the form of a prompt. Depending on the option you select, you get another set of options or you’re prompted to take some action, such as picking a point, selecting objects, or entering a value.

As you work through the exercises, you’ll become intimately familiar with this routine. After you understand the workings of the Tool Sets palette, the Command Line palette prompts, and the dialog boxes, you can almost teach yourself the rest of the program!

Selecting Options from a Shortcut Menu

Now you know that you can select command options by typing them. You can also right-click at any time during the execution of a command to open a shortcut menu containing those same options. For example, in step 2 in the previous exercise, you typed C↵ to tell AutoCAD that you wanted to select the center of the arc. Instead of typing, you can right-click the mouse to open a shortcut menu with options that are currently applicable to the Arc command.

Notice that in addition to the options shown in the Command prompt, the shortcut menu shows you a few more: Enter, Cancel, Pan, and Zoom. The Enter option is the same as pressing ↵. Cancel cancels the current command. Pan and Zoom let you adjust your view as you’re working through the current command.

The shortcut menu is context sensitive, so you see only those options that pertain to the command or activity that is currently in progress. Also, when AutoCAD is expecting a point, an object selection, or a numeric value, right-clicking doesn’t display a shortcut menu. Instead, AutoCAD treats a right-click as ↵.

The location of your cursor when you right-click determines the contents of the shortcut list. A right-click in the Command Line palette input area displays a list of operations you can apply to the command line, such as repeating one of the last several commands you’ve used or copying the most recent history of command activity to the Clipboard.

A right-click in the drawing area when no command is active displays a set of basic options for editing your file, such as repeating the command most recently used, Pan, and Zoom, to name a few (see Figure 2-15).

Figure 2-15:A set of basic list options

If you’re ever in doubt about what to do in AutoCAD, you can right-click to see a list of options. You’ll learn more about these options later in this book. For now, let’s move on to the topic of selecting objects.

In AutoCAD, you can select objects in many ways. There are two categories of selection methods: The first includes object-selection methods unique to AutoCAD, and the second includes the more common selection method used in most popular graphics programs, the Noun/Verb method. Because these two kinds of methods play a major role in working with AutoCAD, it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with them early on.

Using a ![]() -Click and Selection Windows

-Click and Selection Windows

With many AutoCAD commands, you’ll see the Select objects: prompt. Along with this prompt, the cursor changes from crosshairs to a small square (look back at Figure 2-11). Whenever you see the Select objects: prompt and the square Object Selection cursor, you have several options while making your selection. Often, as you select objects on the screen, you’ll change your mind about a selection or accidentally select an object you don’t want. Let’s look at most of the selection options available in AutoCAD and learn what to do when you make the wrong selection.

Before you continue, you’ll turn off two features that, although extremely useful, can be confusing to new users. These features are called Object Snap and Object Snap Tracking. You’ll get a chance to explore these features in depth later in this book, but for now follow these steps to turn them off:

1. Check to see if either Object Snap or Object Snap Tracking is turned on in the status bar. If they’re turned on, they will be a light blue (Figure 2-16).

Figure 2-16:The Object Snap and Object Snap Tracking tools

2. To turn off Object Snap or Object Snap Tracking, click the tool in the status bar. When turned off, they turn gray.

Now, let’s see how to select an object in AutoCAD:

1. Click the Move tool in the Tool Sets palette. You can also choose Modify Move or type M↵.

2. At the Select objects: prompt, click each of the two horizontal lines that constitute the door (trackpad users can tap on the lines). As you know, whenever AutoCAD wants you to select objects, the cursor turns into the small Object Selection cursor. This tells you that you’re in Object Selection mode. As you click an object, it’s highlighted, as shown in Figure 2-17.

If objects don’t become “thicker” as you roll over them with your selection cursor, the Selection preview system variable may be turned off. You can turn it back on by entering selectionpreview↵ 3↵.

3. After making your selections, you may decide to deselect some items. Press F-Z on the keyboard. Notice that one line is no longer highlighted. When you press F-Z, objects are deselected, one at a time, in reverse order of selection.

4. You can deselect objects in another way. ![]() -click (or

-click (or ![]() -tap if you use a trackpad) on the remaining highlighted line. It reverts to a solid line, showing you that it’s no longer selected for editing.

-tap if you use a trackpad) on the remaining highlighted line. It reverts to a solid line, showing you that it’s no longer selected for editing.

Figure 2-17:Selecting the lines of the door and seeing them highlighted

5. By now, you’ve deselected both lines. Let’s try another method for selecting groups of objects. To select objects with a window selection, type W↵. The cursor changes to a Point Selection cursor, and the prompt changes to

Specify first corner:

6. Click and drag a point below and to the left of the rectangle representing the door. Trackpad users should double-tap and drag. As you move your cursor across the screen, a selection window appears and stretches across the drawing area. Also notice that the window has a blue tint.

7. After the selection window completely encloses the door but not the arc, release the mouse button to highlight the entire door. Trackpad users can simply move your finger from the trackpad. This window selects only objects that are completely enclosed by the window, as shown in Figure 2-18.

Don’t confuse the selection window you’re creating here with the zoom window you used in Chapter 1, which defines an area of the drawing you want to enlarge. Remember that the Window option works differently under the Zoom command than it does for other editing commands.

Figure 2-18:Selecting the door in a selection window

8. Press ↵. This tells AutoCAD that you’ve finished selecting objects. It’s important to remember to press ↵ as soon as you finish selecting the objects you want to edit. A new prompt, Specify base point or [Displacement] <Displacement>:, appears. The cursor changes to its Point Selection mode.

Now you’ve seen how the selection process works in AutoCAD—but you’re in the middle of the Move command. The next section discusses the prompt that’s on your screen and describes how to enter base points and displacement distances.

Providing Base Points

When you move or copy objects, AutoCAD prompts you for a base point, which can be a difficult concept to grasp. AutoCAD must be told specifically from where and to where the move occurs. The base point is the exact location from which you determine the distance and direction of the move. After the base point is determined, you can tell AutoCAD where to move the object in relation to that point.

Follow these steps to practice using base points:

1. To select a base point, ![]() -right-click, or if you are using a trackpad, hold

-right-click, or if you are using a trackpad, hold ![]() down and tap with two fingers. The Snap Overrides menu appears, displaying the Object Snap options (see Figure 2-19).

down and tap with two fingers. The Snap Overrides menu appears, displaying the Object Snap options (see Figure 2-19).

When you ![]() -right-click or use a two-finger tap with

-right-click or use a two-finger tap with ![]() , make sure the cursor is within the AutoCAD drawing area; otherwise, you won’t get the results described in this book.

, make sure the cursor is within the AutoCAD drawing area; otherwise, you won’t get the results described in this book.

2. Choose Intersection from the Snap Overrides menu. The Object Snap menu closes.

3. Move the cursor to the lower-right corner of the door. Notice that as you approach the corner, a small X-shaped graphic appears on the corner. This is called an Osnap marker.

4. After the X-shaped marker appears, hold the mouse motionless for a second or two. A tooltip appears, telling you the current osnap point AutoCAD has selected.

Figure 2-19:The Object Snap options

5. Click the mouse button or tap on the trackpad to select the intersection indicated by the Osnap marker. Whenever you see the Osnap marker at the point you want to select, you don’t have to point exactly at the location with your cursor. Just click the mouse to select the exact osnap point (see Figure 2-20). In this case, you selected the exact intersection of two lines.

Figure 2-20:Using the Point Selection cursor and the Osnap marker

6. At the Specify second point or <use first point as displacement>: prompt, ![]() -right-click or press

-right-click or press ![]() and two-finger tap on the trackpad to open the Snap Overrides menu.

and two-finger tap on the trackpad to open the Snap Overrides menu.

7. Click the Endpoint option in the menu.

8. Pick the lower-right end of the arc you drew earlier. (Remember that you need to move your cursor close to the endpoint just until the Osnap marker appears.) The door moves so that the corner connects exactly with the endpoint of the arc (see Figure 2-21).

As you can see, the osnap options let you select specific points on an object. You used Endpoint and Intersection in this exercise, but other options are available. You may have also noticed that the Osnap marker is different for each of the options you used. You’ll learn more about osnaps and the other osnap options that are available in Chapter 3. Now, let’s continue with our look at point selection.

Figure 2-21:Moving the rectangle to its new position using the Endpoint osnap

You may have noticed the statement use first point as displacement in the prompt in step 6. This means that if you press ↵ instead of clicking a point, the object will move a distance based on the coordinates of the point you selected as a base point. If, for example, the point you click for the base point is at coordinate 2,4, the object will move 2 units in the X axis and 4 units in the Y axis.

If you want to specify an exact distance and direction by typing a value, select any point on the screen as a base point. As an alternative, you can type @ followed by ↵ at the base point prompt; then, enter the second point’s location in relative coordinates. Remember that @ means the last point selected. In the next exercise, you’ll try moving the entire door an exact distance of 1 unit at a 45° angle. Metric users will move the door 3 units at a 45° angle. Here are the steps:

1. Click the Move tool in the Tool Sets palette.

2. Type P↵. The set of objects you selected in the previous exercise is highlighted. P is a selection option that selects the previously selected set of objects.

3. You’re still in Object Selection mode, so click the arc to include it in the set of selected objects. The entire door, including the arc, is highlighted.

4. Press ↵ to tell AutoCAD that you’ve finished your selection. The cursor changes to Point Selection mode.

5. At the Specify base point or [Displacement] <Displacement>: prompt, choose a point on the screen between the door and the left side of the screen (see Figure 2-22).

Figure 2-22:The highlighted door and the base point just to the left of the door. Note that the base point doesn’t need to be on the object that you’re moving.

6. Move the cursor around slowly and notice that the door moves as if the base point you selected were attached to it. The door moves with the cursor, at a fixed distance from it. This demonstrates how the base point relates to the objects you select.

7. Type @1<45↵. (Metric users should type @3<45↵.) The door moves to a new location on the screen at a distance of 1 unit (3 for metric users) from its previous location and at an angle of 45°.

If AutoCAD is idle and waiting for a command, you can repeat the last command used by pressing the spacebar or pressing ↵. You can also right-click in the drawing area and select the option at the top of the list. If you right-click the Command Line palette, a shortcut menu offers the commands most recently used.

This exercise illustrates that the base point doesn’t have to be on the object you’re manipulating; it can be virtually anywhere on your drawing. You also saw how to reselect a group of objects that were selected previously without having to duplicate the selection process.

Using Noun/Verb Selection

Nearly all graphics programs today allow the Noun/Verb method for selecting objects. This method requires you to select objects before you issue a command to edit them—that is, you identify the “noun” (the object you want to work on) before you identify the “verb” (the action you want to perform on it). The following exercises show you how to use the Noun/Verb method in AutoCAD.

You’ve seen that when AutoCAD is waiting for a command, it displays the crosshair cursor with the small square. As mentioned, this square is an Object Selection cursor superimposed on the Point Selection cursor. It indicates that you can select objects even while the Command prompt appears at the bottom of the screen and no command is currently active. The square momentarily disappears when you’re in a command that asks you to select points.

Other Selection Options

There are several other selection options you haven’t tried yet. You’ll see how these options work in exercises later in this book. Or, if you’re adventurous, try them now on your own. To use these options, type their keyboard shortcuts (shown in parentheses in the following list) at any Select objects: prompt.

Add (add↵) Switches from Remove mode to the Add mode. See the description for Remove later in this sidebar.

All (all↵) Selects all the objects in a drawing except those in frozen or locked layers. (See Chapter 5 for information on layers.)

Box (b↵) Forces the standard selection window so a left-to-right selection uses a standard window and a right-to-left selection uses a crossing window.

Crossing (c↵) Similar to the Window selection option (described later in this sidebar) but selects anything that is entirely within or crosses through the window that you define.

Crossing Polygon (cp↵) Acts exactly like Window Polygon (see later in this sidebar), but like the Crossing selection option, selects anything that crosses through a polygon boundary.

Fence (f↵) Selects objects that are crossed by a temporary line called a fence. This operation is like using a line to cross out the objects you want to select. After you invoke this option, you can then pick points, as when you’re drawing a series of line segments. After you finish drawing the fence, press ↵, and then go on to select other objects or press ↵ again to finish your selection.

Group (g↵) Allows you to select a group by name.

Last (l↵) Selects the last object you created.

Multiple (m↵) Lets you select several objects first, before AutoCAD highlights them. In a large file, selecting objects individually can cause AutoCAD to pause after each selection while it locates and highlights each object. The Multiple option can speed things up by letting you first select all the objects quickly and then highlight them all by pressing ↵. This has no menu equivalent.

Previous (p↵) Selects the last object or set of objects that was edited or changed.

Remove (r↵) Switches to a selection mode whereby the objects you click are removed from the selection set.

Window (w↵) Forces a standard window selection. This option is useful when your drawing area is too crowded to use the Autoselect feature to place a window around a set of objects. (See the Auto entry later in this sidebar.) It prevents you from accidentally selecting an object with a single pick when you’re placing your window.

Window Polygon (wp↵) Lets you select objects by enclosing them in an irregularly shaped polygon boundary. When you use this option, you see the First polygon point: prompt. You then pick points to define the polygon boundary. As you pick points, the Specify endpoint of line or [Undo]: prompt appears. Select as many points as you need to define the boundary. You can undo boundary line segments as you go by pressing U↵. With the boundary defined, press ↵. The bounded objects are highlighted and the Select objects: prompt returns, allowing you to use more selection options.

The following two selection options are also available but are seldom used. They’re intended for use in creating custom menu options or custom tools:

Auto (au↵) Forces the standard automatic window or crossing window when a point is picked and no object is found. (See the section “Using Autoselect” later in this chapter.) A standard window is produced when the two window corners are picked from left to right. A crossing window is produced when the two corners are picked from right to left. After this option is selected, it remains active for the duration of the current command. Auto is intended for use on systems on which the Autoselect feature has been turned off.

Single (si↵) Forces the current command to select only a single object. If you use this option, you can pick a single object and the current command acts on that object as if you had pressed ↵ immediately after selecting it. This has no menu equivalent.

Try moving objects by first selecting them and then using the Move command:

1. Press the Esc key twice to make sure AutoCAD isn’t in the middle of a command you might have accidentally issued. Then click the arc you drew earlier. The arc is highlighted, and you may also see squares and arrowheads appear at various points on the arc. As stated earlier, these squares and arrowheads are handles that are called grips in AutoCAD. You’ll get a chance to work with them later.

2. Choose Move from the Tool Sets palette. The cursor changes to Point Selection mode. Notice that the grips on the arc disappear but the arc is still selected.

3. At the Specify base point or [Displacement] <Displacement>: prompt, pick any point on the screen. The following prompt appears:

Specify second point or

<use first point as displacement>:

4. Type @1<0↵. Metric users should type @3<0↵. The arc moves to a new location 1 unit (3 units for metric users) to the right.

In this exercise, you picked the arc before issuing the Move command. Then, when you clicked the Move tool, you didn’t see the Select objects: prompt. Instead, AutoCAD assumed you wanted to move the arc that you selected and went directly to the Specify base point or [Displacement] <Displacement>: prompt.

Using Autoselect

Next you’ll move the rest of the door in the same direction by using the Autoselect feature:

1. Click and drag (or double-tap and drag) from a point just above and to the left of the rectangle representing the door. Be sure not to pick the door itself. A selection window appears that you can drag across the screen as you move the cursor. If you move the cursor to the left of the last point selected, the window outline appears dotted with a green tint inside the window (see the first image in Figure 2-23). If you move the cursor to the right of that point, the outline appears solid with a blue tint inside (see the second image in Figure 2-23).

2. While still holding the mouse button, move the cursor to a point below and to the right of the door so that the door is completely enclosed by the window but not the arc, as shown in the second image in Figure 2-23.

Figure 2-23:The dotted window (first image) indicates a crossing selection; the solid window (second image) indicates a standard selection window.

3. Release the mouse button. The door is highlighted (and again, you may see grips appear at the lines’ endpoints and midpoints).

4. Click the Move tool again. Just as in the preceding exercise, the Specify base point or [Displacement] <Displacement>: prompt appears.

5. Pick any point on the screen; then enter @1<0↵. Metric users should enter @3<0↵. The door joins with the arc.

The two selection windows you’ve just seen—the blue solid one and the dotted green one—represent a standard window and a crossing window. If you use a standard window, anything completely within the window is selected. If you use a crossing window, anything that crosses through the window is selected. These two types of windows start automatically when you click any blank portion of the drawing area with a Standard cursor or a Point Selection cursor; hence the name Autoselect.

Next, you’ll select objects with an automatic crossing window:

1. Click and drag (or double-tap and drag) from a point below and to the right of the door. As you move the cursor left, the crossing (dotted) window appears.

2. Position the cursor so that the window encloses the door and part of the arc (see Figure 2-24); then release the mouse button (or tap the trackpad). The entire door, including the arc, is highlighted.

Figure 2-24:The door enclosed by a crossing window

3. Click the Move tool.

4. Pick any point on the screen; then enter @1<180↵. Metric users should type @3<180↵. The door moves back to its original location.

You’ll find that, in most cases, the Autoselect standard and crossing windows are all you need when selecting objects. They really save you time, so you’ll want to become familiar with these features.

Before continuing, choose File Save from the menu bar to save the Door.dwg file. You won’t want to save the changes you make in the next section, so saving now stores the current condition of the file on your hard disk for safekeeping.

Restrictions on Noun/Verb Object Selection

For many of the modifying or construction-oriented commands, the Noun/Verb selection method is inappropriate because for those commands, you must select more than one set of objects. You’ll know whether a command accepts the Noun/Verb selection method right away. Commands that don’t accept the Noun/Verb selection method clear the selection and then ask you to select an object or set of objects.

If you’d like to take a break, now is a good time to do so. If you want, exit AutoCAD, and return to this point in the tutorial later. When you return, start AutoCAD and open the Door.dwg file.

AutoCAD offers selection options in addition to Noun/Verb selection. See Appendix B on the companion website to learn how you can control object-selection methods. That appendix also describes how to change the size of the Standard cursor.

Earlier, when you selected the door, grips appeared at the endpoints, center points, and midpoints of the lines and arcs. You can use grips to make direct changes to the shape of objects or to move and copy them quickly.

If you didn’t see grips on the door in the previous exercise, your version of AutoCAD may have the Grips feature turned off. To turn them on, refer to the information on grips in Appendix B on the companion website.

So far, you’ve seen how operations in AutoCAD have a discrete beginning and ending. For example, to draw an arc, you first issue the Arc command and then go through a series of operations, including answering prompts and picking points. When you’re finished, you have an arc and AutoCAD will be ready for the next command.

The Grips feature, on the other hand, plays by a different set of rules. Grips offer a small yet powerful set of editing functions that don’t conform to the lockstep command/prompt/input routine you’ve seen so far. As you work through the following exercises, it’s helpful to think of grips as a subset of the standard method of operation in AutoCAD. If you’ve used other graphics programs, grip editing will be familiar to you.

To practice using the Grips feature, you’ll make some temporary modifications to the door drawing.

Stretching Lines by Using Grips

In this exercise, you’ll stretch one corner of the door by grabbing the grip points of two lines:

1. Use the Zoom tool in the status bar to adjust your view so the size of the door is similar to what is shown in Figure 2-25.

2. Press the Esc key to make sure you’re not in the middle of a command. Click and drag (or double-tap and drag) from a point below and to the left of the door to start a selection window.

3. Move the cursor above and to the right of the rectangular part of the door and then release the mouse to place the selection window around the door and select it.

4. Place the cursor on the lower-left corner grip of the rectangle, but don’t press the mouse button yet. Notice that the cursor jumps to the grip point and that the grip changes color.

Figure 2-25:Stretching lines by using hot grips. The first image shows the rectangle’s corner being stretched upward. The second image shows the new location of the corner at the top of the arc.

5. Move the cursor to another grip point. Notice again how the cursor jumps to it. When placed on a grip, the cursor moves to the exact center of the grip point. This means, for example, that if the cursor is placed on an endpoint grip, it’s on the exact endpoint of the object.

6. Move the cursor to the upper-left corner grip of the rectangle and click. The grip becomes a solid color and is now a hot grip. The prompt displays the following message:

**STRETCH**

Specify stretch point or [Base point/Copy/Undo/eXit]:

This prompt tells you that Stretch mode is active. Notice the options in the prompt. As you move the cursor, the corner follows and the lines of the rectangle stretch (see Figure 2-25).

You can control the size and color of grips by using the Cursor and Selection settings in the Application Preferences dialog box; see Appendix B on the companion website for details.

7. Move the cursor upward toward the top end of the arc and click that point. The rectangle deforms, with the corner placed at your pick point (see Figure 2-25).

Here you saw that a command called Stretch is issued by clicking a grip point. As you’ll see in these next steps, a handful of other hot-grip commands are also available:

1. Notice that the grips are still active. Click the grip point that you moved before to make it a hot grip again.

2. Right-click (or two-finger tap if you use a trackpad) to open a shortcut menu that contains a list of grip edit options (see Figure 2-26).

Figure 2-26:A list of grip edit options

When you click the joining grip point of two contiguous line segments, AutoCAD selects the overlapping grips of two lines. When you stretch the corner away from its original location, the endpoints of both lines follow.

3. Choose Base Point from the list, and then click a point to the right of the hot grip. Now as you move the cursor, the hot grip moves relative to the cursor.

4. Right-click again, choose Copy from the shortcut menu, and enter @1<-30↵. (Metric users should enter @3<-30↵.) Instead of the hot grip moving and the lines changing, copies of the two lines are made with their endpoints 1 unit (or 3 units for metric users) below and to the right of the first set of endpoints.

5. Pick another point just below the last. More copies are made.

6. Press ↵ or enter X↵ to exit Stretch mode. You can also right-click again and choose Exit from the shortcut menu.

In this exercise, you saw that you can select a base point other than the hot grip. You also saw how you can specify relative coordinates to move or copy a hot grip. Finally, you saw that with grips selected on an object, right-clicking the mouse opens a shortcut menu that contains grip edit options.

Moving and Rotating with Grips

As you’ve just seen, the Grips feature is an alternative method for editing your drawings. You’ve already seen how you can stretch endpoints, but you can do much more with grips. The next exercise demonstrates some other options. You’ll start by undoing the modifications you made in the preceding exercise:

1. Press F-Z or type U↵. The copies of the stretched lines disappear.

2. Press ↵. The deformed door snaps back to its original form.

Pressing ↵ at the Command prompt causes AutoCAD to repeat the last command entered—in this case, F-Z or U.

3. You are going to select the entire door. First click and drag (or double-tap and drag) from a blank area below and to the right of the door.

4. Move the cursor to a location above and to the left of the rectangular portion of the door and release the mouse button or tap the trackpad. Because you went from right to left, you created a crossing window. Recall that the crossing window selects anything enclosed and crossing through the window.

5. Click the lower-left grip of the rectangle to turn it into a hot grip. Just as before, as you move your cursor, the corner stretches.

6. Right-click (or two-finger tap) and choose Move from the shortcut menu. The Command Line palette displays the following:

**MOVE**

Specify move point or [Base point/Copy/Undo/eXit]

Now as you move the cursor, the entire door moves with it.

7. Position the door near the center of the screen and click. The door moves to the center of the screen. Notice that the Command prompt returns but the door remains highlighted, indicating that it’s still selected for the next operation.

8. Click the lower-left grip again, right-click, and choose Rotate from the shortcut menu. The Command Line palette displays the following:

**ROTATE**

Specify rotation angle or [Base point/Copy/Undo/Reference/eXit]:

As you move the cursor, the door rotates about the grip point.

9. Position the cursor so that the door rotates approximately 180° (see Figure 2-27). Then ![]() -click the mouse (hold down

-click the mouse (hold down ![]() and press the left mouse button). A copy of the door appears in the new rotated position, leaving the original door in place.

and press the left mouse button). A copy of the door appears in the new rotated position, leaving the original door in place.

10. Press ↵ to exit Grip Edit mode.

You’ve seen how the Move command is duplicated in a modified way as a hot-grip command. Other hot-grip commands (Stretch, Rotate, Scale, and Mirror) have similar counterparts in the standard set of AutoCAD commands. You’ll see how those work in Chapters 11 and 13, “Using Dimensions” and “Copying Existing Drawings into AutoCAD.”

After you complete any operation by using grips, the objects are still highlighted with their grips active. To clear the grip selection, press the Esc key.

In this exercise, you saw how hot-grip options appear in a shortcut menu. Several other options are available in that menu, including Exit, Base Point, Copy, and Undo.

You can access many of these grip edit options by pressing the spacebar or ↵ while a grip is selected. With each press, the next option becomes active. The options then repeat if you continue to press ↵. ![]() acts as a shortcut to the Copy option. You have to use it only once; then, each time you click a point, a copy is made.

acts as a shortcut to the Copy option. You have to use it only once; then, each time you click a point, a copy is made.

Figure 2-27:Rotating and copying the door by using a hot grip. Notice that more than one object is affected by the grip edit, even though only one grip is hot.

Scaling with Grips

Grips can be used to scale an object graphically to fit between two other objects. For example, a door can be scaled to fit within a door frame. Place the door so its hinge side is at the door frame and the door is oriented properly for the frame. With the door selected, click the grip at the hinge side. Right-click and select Scale. Type R↵, and then click the grip at the hinge again. Click the grip at the end of the arc representing the door swing. Finally, click the opposite side of the door frame.

Using Rotate Reference to Align Objects

You can use the Rotate command’s Reference option to graphically align a set of objects to another object. For example, suppose you want to rotate a set of circles inside a hexagon to align with the corner of the hexagon.

To do this, you can use the Rotate command’s Reference option as follows:

1. Open the Circlehex.dwg file from the sample files on this book’s accompanying website. You’ll use this file to practice using the Reference option.

2. Click the Rotate tool in the Tool Sets palette, select the circles inside the hexagon, and press ↵.

3. At the Specify base point: prompt, use the Center osnap to select the center of the hexagon as represented by the central circle (Figure 2-28). Once you do this, the objects rotate around the selected point as you move your cursor.

Figure 2-28:Rotate using the Reference option.

4. At the Specify rotation angle or [Copy/Reference]: prompt, enter R↵.

5. At the Specify the reference angle <0>: prompt, use the Center osnap to select the center of the hexagon again. You can also enter @↵ since the last point you selected was the center.

6. At the Specify second point: prompt, use the Center osnap to select the center of one of the circles you want to align with the hexagon. Now as you move the cursor, the circle whose center you selected is aligned with the cursor angle.

7. At the Specify the new angle or [Points] <0>: prompt, use the Endpoint osnap to select one of the corners of the hexagon. The circles align with the corners.

8. Close Circlehex.dwg without saving it.

You can also use grips to align objects. Here’s how:

1. Select the object or set of objects and then click a grip. The grip you select becomes the rotation point, so select this first grip carefully.

2. Right-click and select Rotate.

3. Type R↵ and select the grip you just selected and another point to determine the reference angle.

4. Finally, select the new angle for the object or set of objects. If you want to rotate about a point other than the first grip, use the grip’s Base right-click option.

A Quick Summary of the Grips Feature

The exercises in this chapter include only a few of the grips options. You’ll get a chance to use other hot-grip options in later chapters. Meanwhile, here is a summary of the Grips feature:

- Clicking endpoint grips stretches those endpoints.

- Clicking the midpoint grip of a line moves the entire line.

- If two objects meet end to end and you click their overlapping grips, both grips are selected simultaneously.

- You can select multiple grips by holding down

and clicking the desired grips.

and clicking the desired grips. - When a hot grip is selected, the Stretch, Move, Rotate, Scale, and Mirror options are available to you; right-click the mouse.

- You can cycle through the Stretch, Move, Rotate, Scale, and Mirror options by pressing ↵ while a hot grip is selected.

- All the hot-grip options let you make copies of the selected objects by either using the Copy option or holding down

while selecting points.

while selecting points. - All the hot-grip options let you select a base point other than the originally selected hot grip.

Earlier in this chapter, you turned off the Dynamic Input display so you could get an uncluttered view of what was going on in AutoCAD’s display. In this section, you’ll get a chance to explore the Dynamic Input display through grip editing.

You’ll start by going back to the original version of the Door.dwg drawing that you saved earlier:

1. Click the Close icon in the upper-left corner of the drawing area.

2. When you’re asked if you want to save changes, click No.

3. Choose File Open, and then locate and select the Door.dwg file you saved earlier. You can also open the doorsample.dwg file from the sample files you installed from this book’s companion website.

4. The door appears in the condition you left it when you last saved the file.

5. Click the Dynamic Input tool in the status bar to turn it on (Figure 2-29). It should be a light blue color.

6. Click the arc to expose its grips.

Figure 2-29:The Dynamic Input tool in the status bar

7. Place the cursor on the outward-pointing arrow grip at the middle of the arc, but don’t click it. (This is called hovering over a grip.) You see the dimensions of the arc appear. This feature is useful when you need to check the size of objects you’ve drawn (see Figure 2-30).

8. Click the arrow you’re hovering over. The Command prompt appears at the cursor, and the radius dimension changes to a text box.

9. Move the cursor toward the upper-right corner of the drawing area. The radius dimension changes as you move the cursor.

Figure 2-30:Hovering over a grip

10. Enter 4↵. Metric users enter 130↵. As you type, the new value appears in the radius dimension. When you press ↵, the arc changes to the new radius.

11. Press F-Z to revert to the original arc size.

Here you saw the basic methods for using the Dynamic Input display. You can hover over an object’s grip to display its dimensions. Click the grip and, if available, those dimensions can be edited directly through the keyboard. In this example, you were able to change the radius of the arc to an exact value. Depending on the grip you click, you can change a dimension through direct keyboard input. For example, if you want to change the degrees the arc covers instead of its radius, you can click the arrow grip at either end of the arc.

Selecting Multiple Grips And Dynamic Display

You can make more than one grip “hot” by holding down the shift key while clicking grips. But you may find this a little difficult to do when Dynamic Display is turned on. If you are having problems selecting multiple grips, make sure you don’t hover over the first grip too long before you ![]() -click. Hold down the shift key and click the grips as quickly as possible.

-click. Hold down the shift key and click the grips as quickly as possible.

Next, try Dynamic Input display on a line:

1. Click the bottommost line of the door, as shown in Figure 2-31; hover over the rightmost grip on the selected line. Just as with the arc, you can see the dimensions of the line, including its length and directional angle.

Figure 2-31:Selecting a line on the door

2. Click the grip you’re hovering over, and then move the cursor upward and to the right. You see two dimensions: One indicates the overall length and the other shows the change in length of the line. You also see the Command prompt at the cursor. Notice that the dimension indicating the change in length is highlighted (see Figure 2-32).

Figure 2-32:The overall length dimension and the change in length dimension

3. Enter 1 and press the Tab key to increase the length of the line by 1 unit. Metric users should enter 30 and press the Tab key. Now as you move the cursor, the line is locked at a new length that is 1 or 30 units longer than its original length. Also notice that the overall dimension is highlighted. You also see a lock icon on the length dimension (see Figure 2-33).

Figure 2-33:The line locked at a new length

4. Press the Tab key again. The angle value is highlighted.

5. Enter 45 and press the Tab key to lock the angle of the line at 45°.

6. Make sure the cursor isn’t too close to the locked endpoint of the line and then click the left mouse button. The line is now in its new orientation with a length of 4 (130 for metric users) and an angle of 45°, as shown in Figure 2-34.

Figure 2-34:The line’s new length and orientation

You can see that the Dynamic Input display lets you enter specific dimensions for the selected object, making possible precise changes in an object’s size.

You can also use the Dynamic Input display while using other grip-editing features. Try the following exercise to see how the Dynamic Input display works while moving objects:

1. Click and drag from a point above and to the right of the door drawing to start a crossing selection window.

2. Release the mouse button below and to the left to select the entire door drawing.

3. Click the middle grip of the arc.

4. Right-click (or two-finger tap) and choose Move. You see the Command prompt at the cursor with the distance value highlighted. As you move the cursor, you can see the distance and angle values in the Dynamic Input display change (see Figure 2-35).

Figure 2-35:The Dynamic Input display

5. Enter 4, and then press the Tab key. As you move the cursor, the distance from the original location of the arc’s midpoint is locked at 4 units. The angle value is now highlighted and available for editing.

6. Enter 225, and then press the Tab key to lock the angle at 225°.

7. Click a location away from the door drawing. The door moves to its new location, exactly 4 units from its original location.

As you can see from these exercises, the Dynamic Input display adds some helpful methods for editing objects. To summarize, here is a rundown of the basic Dynamic Input display features:

- You can easily turn the Dynamic Input display on or off by clicking the Dynamic Input tool in the status bar.

- You can quickly check the dimensions of an object by selecting it and then hovering over a grip.

- You can alter an object’s dimensions by entering values into the highlighted dimensions of the Dynamic Input display.

- To highlight a different dimension, press the Tab key.

- To accept any changes you’ve made using Dynamic Input display, click the mouse at a location away from the grip you’re editing. You can also press ↵ or the spacebar.

Not all grips offer dimensions that can be edited. If you click the midpoint grip on the line, for example, you won’t see the dimensions of the line, although you’ll see the Command prompt and you’ll be able to enter a new coordinate for the midpoint.

As you’ve seen in the arc and line examples, each object offers a different set of dimensions. If you like the way the Dynamic Input display works, you can experiment on other types of objects.

Typing Coordinates with Dynamic Input

When entering coordinates through the keyboard while Dynamic Input is on, you have to use a slightly different notation for relative and absolute coordinates. If you’re entering relative coordinates, you can leave off the @ sign, so instead of typing @12,9↵, you can simply type 12,9↵. If you are entering absolute coordinates, you need to precede your coordinate list with a # sign. So instead of entering 1,1↵ to specify a point at coordinate 1,1, you would need to enter #1,1↵.

Eventually, you’ll find yourself somewhere without documentation and you’ll have a question about an AutoCAD feature. AutoCAD provides an online help facility that gives you information on nearly any topic related to AutoCAD. Here’s how to find help:

1. Choose Help AutoCAD Help from the menu bar to open the AutoCAD Mac Help website (Figure 2-36).

2. Take a moment to see what is offered on this website. On the left is a column of topics that act like tabs. User’s Guide is at the top followed by Command Reference, Customization Guide, and so on.

3. Click Command Reference. The middle of the page changes to show Commands, Command Modifiers, System Variables, and Glossary along with a section labeled Basics And Tutorials.

4. Click Commands. An alphabetical index appears.

5. Click M Commands under “Topics in the section” and you see a list of command names that start with M.

You also have the Home and Index options in the upper-left corner of the page as well as a search box in the upper right.

Figure 2-36:The AutoCAD Mac Help website

Using Context-Sensitive Help

AutoCAD also provides context-sensitive help to give you information related to the command you’re currently using. To see how this works, try the following:

1. Close or minimize the Help window, and return to the AutoCAD window.

2. Click the Move tool in the Home tab’s Modify panel to start the Move command.

3. Hold down the Function key (fn) and press the F1 key to open the Help window. A description of the Move command appears in the AutoCAD Mac Help website.

4. Press the Esc key to exit the Move command.

Finding Additional Sources of Help

The AutoCAD Mac Help website is the main online source for reference material, but you can also find answers to your questions through the other options in the Help menu bar menu. Here is a brief description of the Help options:

AutoCAD Help Opens the AutoCAD Mac Help website.

Welcome screen In a new installation of AutoCAD, you will see a welcome screen that offers information on how to use AutoCAD. If you’re totally new to AutoCAD, you may want to take advantage of the basic tutorials on how to draw. You’ll also find information on other learning resources.

Getting Started Videos The Getting Started videos offer instructions on the basic features of AutoCAD and how to use them.

Send Feedback The product feedback web page enables you to send comments to Autodesk. The Send Feedback option takes you directly to this page.

Customer Involvement Program The Customer Involvement Program is really a way for Autodesk to monitor the condition of AutoCAD by allowing its customers to send comments about program errors or crashes. This voluntary program lets you participate anonymously, or you can provide contact information for follow-up contacts.

You can also obtain general information about your version of AutoCAD by choosing AutoCAD About AutoCAD. This opens the About window. Click the Product Information button to find your serial number, product key, and other license information.

Displaying Data in the Command Line Palette

You may have noticed that as you work in AutoCAD, the activity displayed in the Command Line palette scrolls up. Sometimes, it’s helpful to view information that has scrolled past the view shown in the Command Line palette. For example, you can review the command activity from your session to check input values or to recall other data-entry information. Try the following exercise to see how scrolling in the Command Line palette might be helpful:

1. Choose Tools Inquiry List from the menu bar or type LIST↵.

2. At the Select objects: prompt, click the arc and press ↵. Information about the arc is displayed in the AutoCAD Command Line palette. Figure 2-37 shows the Command Line palette stretched to show all of the information from the List command. Toward the bottom is the list of the arc’s properties. Don’t worry if the meaning of some listed properties isn’t obvious yet; as you work through this book, you’ll learn what the properties of an object mean.

Figure 2-37:The stretched Command Line palette showing the data displayed by the List command

3. Expand the Command Line palette using the disclosure triangle at the right of the palette. Use the scroll bar to the right of the Command Line palette to scroll up the contents of the palette.

The scroll bar to the right of the Command Line palette lets you scroll to earlier events. You can even have AutoCAD record the Command Line palette information in a text file.

When you have more than one document open, the Command Line palette displays a listing for the drawing that is currently active.

Displaying the Properties of an Object

While we’re on the subject of displaying information, you’ll want to know about the Properties Inspector palette. In the preceding exercise, you saw how the List command showed some information regarding the properties of an object, such as the location of an arc’s center and endpoints. You can also select an object to display its properties in the Properties Inspector palette.

To see how the Properties Inspector palette works firsthand, try the following exercise:

1. Select the arc in the drawing. The Properties Inspector palette displays a list of the arc’s properties. Don’t worry if many of the items in this palette are undecipherable; you’ll learn more about this palette as you work through the early chapters of this book. For now, just be aware that you can select an object to display its properties. You can also use the Properties Inspector palette to modify many of the properties listed (see Figure 2-38).

Figure 2-38:The Properties Inspector palette

2. Click and drag the scroll bar to the right to see more of the object’s properties.

3. You’re finished with the door drawing, so choose File Close from the menu bar.

4. In the Save Changes dialog box, click the No button. (You’ve already saved this file just as you want it, so you don’t need to save it again.)

You may notice the Essential and All options in the upper-right side of the Properties Inspector. These two options enable you to choose the level of information displayed in the palette. The Essential option limits the number of properties displayed to a few of the basic ones like layer and linetype. The All option displays a complete set of properties.

Specify distances with coordinates. One of the most basic skills you need to learn is how to indicate exact distances through the keyboard. AutoCAD uses a simple annotation system to indicate distance and direction.

Master It What would you type to indicate a relative distance of 14 units at a 45° angle?

Interpret the cursor modes and understand prompts. AutoCAD’s cursor changes its shape depending on the command that is currently active. These different cursor modes can give you a clue regarding what you should be doing.

Master It Describe the Point Selection cursor and the Object Selection cursor.

Select objects and edit with grips. Grips are small squares or arrowheads that appear at key points on the object when they’re selected. They offer a powerful way to edit objects.

Master It How do you select multiple grips?

Use Dynamic Input. Besides grips, objects display their dimensional properties when selected. These dimensional properties can be edited to change an object’s shape.

Master It How do you turn on Dynamic Input? And once it’s on, what key lets you shift between the different dimensions of an object?

Get help. AutoCAD’s Help window is thorough in its coverage of AutoCAD’s features. New and experienced users alike can often find answers to their questions through the Help window, so it pays to become familiar with it.

Master It What keyboard key do you press for context-sensitive help?

Display data in the Command Line palette. AutoCAD offers the Command Line palette, which keeps a running account of the commands you use. This can be helpful in retrieving input that you’ve entered when constructing your drawing.

Master It Name a command that displays its results in the Command Line palette.

Display the properties of an object. The Properties Inspector palette is one of the most useful sources for drawing information. Not only does it list the properties of an object, it lets you change the shape, color, and other properties of objects.

Master It How do you open the Properties Inspector palette for a particular object?