PROTECT THE ENVIRONMENT

Implementing Green, Sustainable Projects

Force 10: Environmentalism. This important force involves protecting the environment. When the issue of global warming first surfaced in the 1980s, it stirred up much public debate and concern throughout the world. However, business leaders resisted the issue of global warming, expecting they would have to pay a lot of money to address the problems causing it. While most agreed that climate change was occurring, views differed regarding its origins, and finding solutions was not a priority to the business world at large.

Today, most (if not all) businesses recognize that climate change is a problem, and some businesses are making attempts to solve it, resulting in a wave of sustainability and environmental projects. However, too many organizations are currently caught in what may be called a green slump, struggling to engage in green projects and making far less progress than is actually required.

From an organizational perspective, going green offers employees, contractors, volunteers, and members the opportunity to influence the green movement through involvement and contribution. The challenge is to create the correct approach to involve these people—one that includes teaching, convincing, communicating, enabling, supporting, and encouraging participation in the green process. The best way to accomplish this is through the human capital strategy.

This chapter shows the importance of protecting the environment with a variety of green sustainable projects. The sheer number of potential green projects and initiatives, and the fact that not everyone is buying into the issues, brings into focus the need for this chapter. Many individuals do not see the need for action because they do not understand the issues or know what they can do to help. Some people do not understand green projects and sustainability efforts, feel inconvenienced by them, believe they are negatively affected in one way or another by project outcomes, or perceive projects to require unrealistic investment.

This chapter presents the many facets of the green revolution and how organizations are managing to go green. It explores the value of green projects and what must be accomplished by the CHRO to deliver results to protect the environment.

Opening Story: Interface

Interface Inc. began in 1973 when founder and chairman Ray C. Anderson recognized the need for flexible floorcoverings that would facilitate the emerging technologies of the modern office. Over the years, Interface grew its core business and expanded through more than fifty acquisitions to become the world’s largest producer of modular carpet, with manufacturing on four continents and sales in more than 110 countries. Today, Interface is a billion-dollar corporation, named by Fortune magazine as one of the “Most Admired Companies in America” and “100 Best Companies to Work For.”

In 1994, while preparing remarks on Interface’s environmental vision for a company task-force meeting, Ray Anderson experienced a fundamental perspective change. Seeking inspiration for his speech, Ray read Paul Hawken’s “The Ecology of Commerce” and was deeply moved—an experience he described as an epiphany. It awakened Ray to the urgent need to set a new course for Interface toward sustainability.

In that year, Anderson set a daring goal for his commercial carpet company: to take nothing from the earth that cannot be replaced by the earth. At the time, carpet manufacturing was a toxic petroleum-based process that released immense amounts of air and water pollution and created tons of waste. In the fifteen years since Anderson’s call for change, Interface has accomplished the following:

• Cut greenhouse gas emissions by 82 percent

• Cut fossil fuel consumption by 60 percent

• Cut waste by 66 percent

• Cut water use by 75 percent

• Invented and patented new machines, materials, and manufacturing processes

• Increased sales by 66 percent, doubled earnings, and raised profit margins

The journey to a fully sustainable Interface is like climbing “a mountain higher than Everest”—difficult, yes, but with a careful and attentive plan, not impossible. Interface created a framework for the climb called “Seven Fronts on Mount Sustainability”:

Front #1—Eliminate Waste: Eliminate all forms of waste in every area of the business.

Front #2—Benign Emissions: Eliminate toxic substances from products, vehicles, and facilities.

Front #3—Renewable Energy: Operate facilities with 100 percent renewable energy.

Front #4—Closing the Loop: Redesign processes and products to close the technical loop using recycled and bio-based materials.

Front #5—Efficient Transportation: Transport people and products efficiently to eliminate waste and emissions.

Front #6—Sensitizing Stakeholders: Create a culture that uses sustainability principles to improve the lives and livelihoods of all our stakeholders.

Front #7—Redesign Commerce: Create a new business model that demonstrates and supports the value of sustainability-based commerce.

As part of its Mission Zero commitment, Interface has set a goal to source 100 percent of energy needs from renewable sources by 2020. To achieve this, Interface has a simple strategy—improve energy efficiency and increase use of renewable energy. They have taken an aggressive approach to reach this goal, installing renewable energy systems at factories and purchasing renewable energy for facilities around the world. By 2013, five of its seven factories operated with 100 percent renewable electricity, and 35 percent of its total energy use was from renewable sources.

The vision and mission of Interface focuses on sustainability.

Ray Anderson and Interface have been featured in three documentary films, including The Corporation and So Right, So Smart. In 1997, Anderson was named cochair of the President’s Council on Sustainable Development, and in 2006, he served on the national advisory committee that helped guide the Presidential Climate Action Project, a two-year, $2 million project administered by the Wirth Chair School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado. He and Interface have been featured in the New York Times, Fortune, Fast Company, and other publications.

Anderson died on August 8, 2011, twenty months after being diagnosed with cancer. On July 28, 2012, Anderson’s family relaunched the Ray C. Anderson Foundation with a new purpose. Originally created to fund Ray Anderson’s personal philanthropic giving, family members announced the rebirth and refocus of the foundation on Anderson’s birthday, nearly one year after his 2011 death. The purpose of the Ray C. Anderson Foundation is to perpetuate shared values and continue the legacy that Anderson left behind. The Ray C. Anderson Foundation is a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) organization whose mission is to create a brighter, sustainable world through the funding of innovative projects that promote and advance the concepts of sustainable production and consumption. The world needs more leaders like Ray C. Anderson and organizations like Interface.

The Green Revolution

A green revolution is occurring throughout the world, and this effort toward fundamental change is particularly pervasive in the United States. Perhaps Thomas Friedman captures this revolution best in his bestselling book Hot, Flat, and Crowded, in which he makes the case for a green revolution that should sweep through organizations, cities, communities, and governments to create what he describes as the Energy Climate Era. Here are a few examples of green initiatives.

Green Cities

Discussions about environmental issues often dwell on cities, focusing on their congestion, inefficiencies, and unmanageable challenges. Tall buildings, consuming enormous amounts of energy, and heavy traffic, inundating the environment with carbon emissions, are obvious environmental hazards. The cities themselves have taken the brunt of many of the social ills that stem from poverty, illness, crime, pollution, open sewers, and exhaust fumes. Despite these burdens, however, cities—with their great density—offer perhaps the best opportunities for environmentally friendly places to live and work. For example, the population density in Manhattan is sixty-seven thousand people per square mile, more than eight hundred times the nation as a whole and roughly thirty times the city of Los Angeles. In dense cities, residents can often live without the convenience of an automobile. Working near home allows people to live without the ecological disasters of cars, in contrast to workers who live in rural or suburban areas and have to use an automobile for every trip. In cities, people can engage in environmentally friendly habits such as bicycling, using mass transit, and walking while supporting each other as a community. Some cities are working hard to increase their residential appeal, which reduces the environmental burden caused by the mass exodus of the workforce commuting home at the end of the day. Some cities, airports, and ports are striving to be the greenest in the world, with much progress.

Green Organizations

The starting point for most organizations is to organize properly for green initiatives. This process begins with a mission statement, a vision statement, and a value statement that all incorporate green issues and sustainability efforts. This also involves the assignment of specific responsibilities to individuals involved in green projects. Role definition for all organizational stakeholders is a must if involvement, support, encouragement, and accomplishment of green objectives is the goal. An executive should be assigned the responsibility of environmental and sustainability efforts. Ideally this should be the CHRO. Figure 12.1 highlights the seven actions that must be taken to create a green organization.

Employees must understand the necessity for green projects and be aware of important environmental issues. Formal and informal meetings and communications using the plethora of social media tools can help. Learning programs make employees aware of the issues and the necessity to make improvements and adjustments. Brochures, guides, fact sheets, program descriptions, and progress reports help promote and encourage green project participation.

Organizational leaders must “practice what they preach” through visible and substantial green projects. These projects should be communicated to the organization, and their successes should be clearly documented. An example of a highly visible project is one that has been undertaken by Hewlett-Packard. A problem exists with the mountains of consumer electronics being disposed of in landfills. To set an example in this important area, HP has collected more than three billion pounds of e-waste (the weight of three thousand jumbo jets) since 1987. More than 75 percent of ink cartridges and 24 percent of HP LaserJet toner cartridges are now manufactured with “closed loop” recycled plastic. HP remanufacturing programs give IT hardware, such as servers, storage, and networking products, a new lease on life, reducing environmental impacts from disposal.

Organizations are enabling stakeholders to be involved in green projects in their communities and in their personal lives. Organizations assist employees with recycling programs and support employees in a variety of ways to understand, promote, and be involved in green initiatives. For example, eight communities across the United States joined to create Climate Prosperity Project Inc., a nonprofit organization to address climate change and pursue economic development. The communities—Silicon Valley / San Jose, CA; Portland, OR; St. Louise, MO/IL; Denver, CO; Seattle, WA; Southwest, FL; Montgomery County, MD; and the State of Delaware—are convinced that climate change presents not only an environmental imperative but also an extraordinary economic opportunity.

Progressive companies are rewarding stakeholders for being involved in green efforts. For example, Southern Company has launched EarthCents programs, which include new and existing programs and educational efforts to help reduce residential and commercial energy consumption. The benefits of EarthCents include not only wise use of energy but also reduction of costs that hit the pockets of their customers. In addition, shareholders are rewarded because corporate costs are reduced and capital expenditures are avoided. Through EarthCents education programs, employees have an opportunity to engage in stewardship that is highly valued and recognized by the organization. Some organizations provide quarterly or annual awards for green efforts by employees or groups of employees. Others provide bonuses for green ideas.

It is important for green-project success to be monitored and adjustments to be made along the way. Results must be communicated to stakeholders even if they show processes are not working well. The lobby of the International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD) boasts a large chart showing the progress of green projects. Measurement is a critical part of accountability, and making adjustments as measures are taken is a great way to keep projects on track.

Green organizations purchase green materials and supplies through their procurement functions by specifying and requiring green products. This is important with cleaning materials, for example, which can be toxic and hazardous to the environment. Purchasing green paper products is a highly visible way to contribute to the green movement, because it touches so many employees and stakeholders.

Progressive green organizations ensure that their products and services are sensitive to environmental issues and support sustainability efforts. This may mean that new products are developed to support the green movement. For example, Office Depot/OfficeMax researched how to transform its market based on creating a green office. These offerings include a green book catalog as well as a green office website. This site provides customers with definitions of terms and certifications, such as postconsumer recycled content. Through its effort, Office Depot/OfficeMax reinforces to businesses that there are real cost-saving opportunities with green products.

Collectively, these efforts are being taken up by thousands of organizations. If implemented properly, they can make significant progress with sustainability efforts. The important point is to make sure the value and success of these projects are known to stakeholders responsible for the design, implementation, and funding of projects.

Green Buildings

Green organizations should be housed in green buildings, which represent another important opportunity and challenge. The opportunity exists because there are more than thirty million buildings in the United States, most of which are anything but green. These buildings consume about one-quarter of the global wood harvest, one-sixth of its fresh water, and two-fifths of the material and energy flows. They account for about 40 percent of primary energy use. A typical house in the United States produces twenty-six thousand pounds of greenhouse gases each year, enough to fill up a Goodyear blimp. The challenge is that becoming a green building is not easy.

The good news is that major building projects across the country are now largely adhering to new benchmarks with environmentally sustainable construction standards, focusing not only on recycled building materials but energy efficiency as well. At the center of this movement is a certification program offered by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). This program, known as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, is a third-party verification system to show that a building was designed and built using true environmental standards, including energy savings, water efficiency, and CO2 emissions reduction. Almost all the large-scale commercial projects in the United States are now LEED projects, and given that more than half of greenhouse gases come from buildings (compared to 9 percent for passenger vehicles), this is huge step in the right direction.

Green Workplaces

When people are not at home, they are usually at work, so the workplace represents another important area of focus for green initiatives. The workplace provides an opportunity for people to function in a green environment, learn about green issues, experiment with green projects, and observe cost savings at the same time. Figure 12.2 shows opportunities to make a workplace green.

Perhaps the greatest opportunity to save money and have a positive impact on the environment is to take advantage of the many possible options to let people work at home. Some organizations allow two or more employees to use a single assigned workplace and rotate schedules. Sometimes several people share office space close to their home at a reduced cost. Of course, the greatest environmental benefit comes from working at home full-time. One study revealed that 1,478 tons of carbon dioxide was prevented from being released into the environment each year when 350 employees were allowed to work at home. Many organizations have been using telecommuting practices for years. Not only does the practice contribute to the environmental good, but many find that allowing employees to work at home creates a significant savings in real estate costs, as they are able to give up office space when the leases expire. Companies also find that productivity increases, because employees working at home are able to maintain larger workloads. Other benefits include gains in retention, job satisfaction, and talent recruitment, as described in Chapter 6.

Another important savings at the workplace can come from the reduced use of water, electricity, and natural gas. Although technology, design, and control mechanisms can make a difference, behavior change by the workforce can have the greatest impact. Many cost-saving processes can lower utility bills and help the environment. Simply shutting down computers at the end of the day and using motion-detection lighting can have a big impact on energy usage and operating costs.

Since the 1980s, businesses have been exploring ways to maintain a green workplace, from paper and toner cartridges to almost every office product category. Unfortunately, the traditional perception of making an office green is that costs will increase. This is not necessarily true. Even when items cost more initially, there is often a payback in the long run. Improvements have been made in the production of green office products. Businesses need to recognize that there is a green cost continuum. Some products, such as remanufactured ink or toner cartridges, are greener and less expensive. Also, investments in durable items rather than disposable ones, as well as in reusable and energy efficient items for the office, can mean dollars added to the company’s bottom line due to decreased operating costs and repurchase costs.

Maintaining a green work environment creates an important image for consumers, employees, and others who care about the green movement. Consumers are attracted to companies that are environmentally responsible, and employees often want to work for companies that put the environment first. This can be an attractive recruiting tool, particularly for younger employees who want to work in this type of environment.

Indoor air quality is also a critical issue for employee health and well-being. Mold in the workplace—along with exposure to laser toner, cleaning agents, carbon monoxide, aerosols, and other items—can lead to a variety of ailments for employees, such as asthma and nasal irritations. The proper use of cleaning products and regular heating, ventilation, and air conditioning maintenance will make a difference.

The workplace is a fertile ground for green initiatives. It represents a major opportunity to shape employees’ behavior. To do so will require a systematic approach to show the value, importance, and success of a variety of green initiatives.

Green Meetings

One of the top offenders to the environment is the meetings and events industry, rated only second to the construction industry. Each year, tens of thousands of meetings are organized globally where people convene to discuss all types of issues. Long-distance travel, large meeting places, and constant hotel stays have a huge impact on the environment. For example, the annual conference of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM)—the world’s largest association of human resources professionals with about 275,000 members—attracts HR specialists, managers, and executives from around the world. A recent meeting in Las Vegas drew approximately 12,000 participants, about one-fourth of them from outside the United States. Everyone travels to the meeting; most of the travel is by air, and many flights involve long distances. The conference accommodates nearly 2,000 exhibitors, and some exhibits are so large that they need to be trucked in prior to the conference. Attendees take up thousands of hotel rooms, consume a tremendous amount of local transportation, and then travel back to their original destination. The effect this one meeting has on the environment is significant. Multiply this by all types of private company meetings, professional associations, trade shows, and special events, and it becomes clear why this industry is destroying the environment.

A few experts in the green and environmental movements suggest that, for the most part, these large-scale meetings should go away. In this era, such conferences add little to knowledge and understanding, they damage the environment, and much of what they do can be accomplished in other ways. While this is a harsh position, the industry is facing challenges on several fronts. Technology has enabled people to meet more conveniently and without the cost of the travel. Many executives are questioning the value of this expenditure. The recent global recession has put many of these events in the crosshairs of cost-cutting CEOs.

Green Energy

Many observers see green energy as the key to solving the climate-change problem. They posit that clean energy is the solution to all environmental ills. The topic of clean energy garners much attention, focus, and money, although some projections are bleak as energy demand increases. There are many projects and programs in place to tackle the issue.

Suppliers of energy realize that the best way to address the crisis is simply to save energy. This is why electrical power companies and other energy providers are advising consumers on ways to save electricity. Indeed, this may be the only way for them to meet the demand. This involves saving energy through efficient light bulbs, pumps, and motors; good building design; and refined processes.

A variety of new green power sources are being developed from solar, wind, small hydro, biomass, and geothermal sources. These are being funded in part by business energy users as they purchase renewable energy certificates (REC). With the RECs, businesses are buying power that is purchased from the new power sources and placed on the grid. It is impossible to hook a business up directly to a wind farm, but the business can purchase the equivalent of the power they need to be generated by the wind farm. It is like trading in the commodity market. This is providing significant funding for new sources of green power.

Green Technology

A bright spot in the green revolution is that the development of new technologies are, in some cases, central to green projects and sustainability efforts. Some advocates describe green technology as a huge growth opportunity for the next decade. Just as information technology exploded in the 1990s, green technology is set to be the next major growth sector. Renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, green-building design, environmentally friendly construction and retrofits, greater efficiencies in lighting and appliances, smart grids, clean-energy transportation—all are markets of promise to generate jobs and profits globally.

Green technology does not have to represent huge projects; small devices can make a difference. Consider, for example, power adaptors—the boxes on charging cords that that either sit between the plug and the mobile phone or are integrated with the plug. There are about five billion power adaptor devices in use worldwide. The function of the power adapter is to convert high-voltage alternating current into the low-voltage direct current that is used for charging mobile phones, tablets, and other electronic devices. Until recently, the conversion was made using copper wire, and as much as 80 percent of the power was lost in the conversion as waste heat. Now conversion can be made more efficiently with an integrated circuit, with as little as 20 percent of the power being lost. It took some time for manufacturers, utilities, and state and federal authorities to work together to adopt the new technology, but for consumers, the switches mean lower power bills and smaller and lighter power adapters. Although they cost a little more to produce, the savings are tremendous. For the world as whole, this has meant a drop in global power consumption that is worth about $2 billion per year and saves thirteen million tons of carbon emissions annually.

Technology projects are fast growing and almost limitless. Green technology patents are on a growth path, and the U.S. government is expediting the patent process, reducing the traditional time it takes for a patent to be processed from forty months to one year. Faster patent reviews mean that firms can arrange financing more easily. This action should generate additional research and development from private firms (large and small) and universities as well. New products will likely emerge, including patents for hardware, software, and communication devices to monitor commercial and home energy use. All types of technologies are being developed to cut carbon emissions.

Managing the Change to Green

The landscape is covered with all types of green initiatives and projects, and the CHRO should have the responsibility for these projects. Sustainability must be integrated, managed, and properly implemented to reap the greatest rewards. There are several factors that help drive the changes that are taking place in the green revolution.

The number one driver for implementing green projects is the image it presents of an organization. Green is in vogue in all types of organizations. Organizations recognize that it is in their best interests for their constituents, consumers, employees, stakeholders, and the general public to view them as environmentally friendly.

In 2009, when Mike Duke took over as CEO of Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, which uses more electricity than any other private organization in the world and has the second-largest trucking company, his message to employees in a time of recession covered the expected topics about providing good service, keeping costs low, and beating the competition. However, he also talked about sustainability. Specifically, he described many of the environmental projects that Wal-Mart had undertaken to reduce transportation and energy costs. He emphasized that these sustainability efforts must be accelerated and broadened in the future, regardless of the recession.

Why would the world’s largest retailer, with approximately $500 billion in net sales and eleven thousand stores in twenty-seven countries, focus so much on the green issue? Wal-Mart sees this as a way to provide low prices as they manage and control costs, which enables them to stay profitable, drive innovation, and help many of their customers through difficult times.

Sustainability, which includes sustaining the life of an organization, the profits of the organization, and society at large, is a part of Wal-Mart’s strategy. A green strategy often focuses on protecting and restoring the ecosystem, and it involves actions and conditions that affect the earth’s ecology, including reduction of climate change, preservation of natural resources, and prevention of toxic waste hazards.

During the last two decades, organizations have begun to incorporate strategies for sustainability with tremendous focus on green elements. Like all strategies, these plans must evolve from a clear understanding of where the organization is and where it can go, and they require the input and buy-in of all stakeholders. Plans should show how the strategies can be implemented and achieved with effort, determination, and deliberation. Organizations must review these strategies occasionally to see how they are working and apply great leadership throughout the process to make sure that each strategy is challenging, feasible, workable, and successful.

There is often a perception that a clean environment is going to cost everyone—that green initiatives come with a premium. This is not always the case. In fact, there are more opportunities for positive ROI values with green projects than negative ROI values. Smart, progressive companies use their environmental strategies to innovate, create value, and build competitive advantage, and the opportunities are endless. To convince a group of money-conscious executives to undertake green projects, a method must exist that shows there is value in these projects that will ensure continued funding and growth.

According to Andrew Winston, green projects may represent the best way to stimulate the economy and keep companies prosperous. He suggests four strategies to turn green into gold:

• Get lean. Generate immediate bottom-line savings by reducing energy use and waste.

• Get smart. Use value-chain data to cut costs, reduce risks, and focus innovation efforts.

• Get creative. Pose theoretical questions that force you to find solutions to tomorrow’s challenges today.

• Get engaged. Give employees ownership of environmental goals and the tools to act on them.10

As we continue to work to manage the change to green, one of the main challenges is to convince a variety of stakeholders about the value that green projects deliver, up to and including the financial ROI.

Another important element of managing change involves taking advantage of the “green-collar” economy. This concept essentially addresses two of the biggest problems facing most countries: the economy and the environment. A green job is defined as one with “decent wages and benefits that can support a family. It has to be part of a real career path, with upward mobility. And it needs to reduce waste and pollution and benefit the environment.”11

Development of new green products and services, such as new sources of energy and new technologies, leads to new jobs. These jobs are significant in number, and the investments are large enough to drive the economy. In addition to the bottom-line contribution, both to those who obtain the new jobs and the economy at large, green jobs ultimately have a positive environmental impact. In the United States, the best example of perpetuating a green-collar economy is the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which included more than $60 billion in clean-energy investment intended to help jumpstart the economy and build clean energy jobs for tomorrow. This investment is expected to easily generate a more than $500 billion return in new jobs, business startups, expansion, and energy savings.12

The fifty interviews conducted by MIT in its Business of Sustainability Initiative revealed significant behavior changes that have taken place and must continue to take place. As organizations work to address environmental sustainability projects, there are eight management behaviors for leaders to keep in mind:

1. Sustainability projects will find you; it is hard to escape it. It is best to plan for it now.

2. Do not be surprised if you see unexpected productivity gains from green projects.

3. Your reputation is at stake; not addressing the green issues could seriously tarnish your efforts.

4. Strategy is needed and must be executed to see the system as a whole and to connect the dots.

5. Sustainability challenges demand innovation that is more iterative, more patient, and more diverse.

6. There must be collaboration across all boundaries to be successful.

7. The fear of risks has skyrocketed, creating a need for any practice or behavior that would access risk and reduce it.

8. The first adaptors with particular processes will be the winners.13

With this push and need for sustainability, there must be a focus on changing the behavior of people involved in this process. Attitudes, perceptions, awareness, and the barriers to actions must be addressed. As illustrated in the next chapter, there are many obstacles that can kill a project before it has a chance to add value. The measurement process described in this book can be used to assess a project’s success and allow leaders to make adjustments to drive results.

The Value of Green Projects

“Is it worth it?” When asked this question about new or proposed green projects and sustainability initiatives, many executives, government officials, community leaders, and others involved with the environmental movement will answer with a resounding “Yes!” Others, however, respond with hesitancy. Some need convincing that there is value in going green.

The ultimate payoff of green projects and sustainability efforts is addressing climate change, deforestation, famine, and many other issues we face. Unfortunately, progress is lacking. Even at the microlevel, as hundreds of green projects are initiated every day, progress is minimal.

The Green Killers

When we consider the problems facing the planet and its future state, the need for healing is evident. Unfortunately, there are some people who do not support sustainability efforts. While many individuals stand in the way of progress, much of their inertia is based on misunderstandings of the need to make improvements. The sad truth is that people struggle to change. Elected officials and business leaders are not highly respected these days, and so when they tell us, “Trust me, this is good for all of us, just go and do it,” people tend to tune them out.

Defining Value

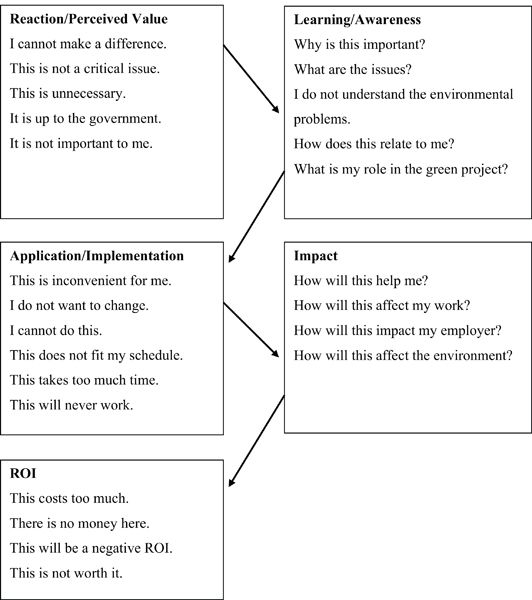

Figure 12.3 shows some of the questions and issues that often arise when people are first introduced to green projects and sustainability efforts. They represent less-than-supportive attitudes toward green initiatives. These “green killers” inhibit progress and success.

The killers are categorized along a five-level results framework that is fundamental to the ROI Methodology, which is described in more detail in Chapter 14. The levels of data follow a chain of impact that must be in place for a green project to add business value.

The first level of value is reaction and perceived value. As the “Reaction/Perceived Value” section of Figure 12.3 shows, many people are still apathetic or believe their actions can make no real difference. They seem to think that sustainability is someone else’s problem or that the only way to change it is through regulations and laws tackling the energy companies and the big polluters. Because of these initial reactions to green projects, CHROs must position the projects so employees, customers, and suppliers can perceive them as relevant and valuable.

The second level of value is learning. Try this experiment. Take five of the important elements that describe climate change, such as change in average weather over time, increase in CO2 in atmosphere, local species extinction due to global loss of biodiversity, variations in solar radiation, or abrupt climate change, and ask your friends if they understand their meaning. Chances are, out of ten people, only one will be able to describe all five. There has not been enough specific information offered about climate change, particularly for the population born prior to 1970. Sustainability issues are now a part of most academic course curricula, but for the majority of the world’s population, there has been limited education.

Consider the simple issue of changing to an alternative type of light bulb. In the United States, lighting represents about 20 percent of all electricity usage. A standard incandescent light bulb costs around $2 and uses about $20 of electricity per year. In contrast, a low-energy bulb costs about $8–$10 but only uses about $4 of electricity per year. With a cost reduction of $16 per year and an investment of $10, the benefits clearly exceed the costs.

While it makes sense financially, as well as environmentally, for people to change their bulbs, changing to energy-efficient lighting is a behavior many consumers cannot conceive. Manufacturers of energy efficient bulbs blame this on public apathy or lack of awareness. In this case, the public needs to be aware not only of how a particular green project can work but also of its benefits to the climate as well as the pocketbook. The learning that must take place is substantial. The more people know, the less resistant they will become. Even with government interventions phasing out the less efficient incandescent bulbs and offering only energy efficient bulbs, educating the public is essential.

The third level of value is application and implementation. Perhaps the greatest problem with green projects is people’s inability to change current habits. Essentially, there is often limited application or implementation of processes focusing on green outcomes, at least at the level that may be needed to achieve desired results. Sometimes people do not do what is needed because it is inconvenient, it requires a change of habit, or they think they cannot do it. Others think that it may take too much time and see many barriers to the actual success of the project. Still others see that they can do it but need support. Consider this story:

After much political wrangling, you manage to install energy-efficient lighting in a high-end hotel restaurant. The project will save thousands of dollars in electricity costs while preventing tons of carbon emissions from entering the atmosphere. It is the “rubber meets the road” of the sustainability movement, the blue-collar work of the climate battle. The restaurant opens, and the manager is put off by the sight of compact fluorescent bulbs. He removes the bulbs, throws them out, and replaces them with inefficient halogens. Not because he is ignorant or because he does not care, but because he has a business to run, and he is doing it the best way he knows how. His perspective is: you do not put energy-efficient fluorescent bulbs in a fancy restaurant any more than you would put Cool Whip on an éclair.

Nonetheless, this is what your sustainability efforts have brought you: a wasted design and installation fee; inefficient lighting; the manager’s loss of faith in green technology; hundreds of expensive compact fluorescent bulbs that, instead of being reused (at the very least), are now leeching costs for new bulbs and installation.14

There must be bottom-line consequences for many people to change their behaviors, particularly toward an outcome they believe is still somewhat elusive.

The fourth level of value is impact. Most individuals sponsoring green projects want to know the impact a project is going to have and the specific measures it will drive. Those involved want to know how it will affect them personally. Employees want to know how it will affect their work or maybe even their employer. Others want to know the impact on a community group or the city where they live. Some want to know what affect it has on the environment or how it helps the sustainability effort. Unfortunately, this evidence is often needed before the decision to begin is made. If the project involves savings in electricity usage, for example, some want to know before investing how much savings will occur. While there may be enough credible data to make a reliable forecast, the convincing needs to be strong. Some of the important impacts are energy use, carbon emissions, recycle volume, fuel costs, supplies costs, and landfill costs.

From our work at the ROI Institute, we recognize that impact data are the most critical data executives want to see. Executives are often willing to invest in green projects if there are intangible benefits that do not figure into the ROI calculation. So it is the impact data that are critical, and this must be developed for many executives to invest.

The fifth level of value is return on investment (ROI). Some people believe that green projects will result in a negative payoff. There is often an impression that a premium price is paid for anything that is green in nature. Perhaps this is based on a memory of when, years ago, recycled paper was expensive. In reality, most green products can actually save money in the long term, but the perception still exists that the cost of green outweighs the benefits, resulting in a negative ROI. As such, people conclude that green is not worth it. More examples are needed to show the costs versus benefits for a variety of projects.15

Change Toward Green

The green killers lead to inaction or inappropriate action affecting outcomes associated with green projects. While it is disappointing that attitudes, perceptions, lack of interest, and purposeful (or not) green washing seem to get in the way of making progress with sustainability efforts, these barriers exist with almost any type of change. For change to occur, employees must have a favorable reaction, understand the issues, and take appropriate action. The good news is that most people have a genuine interest in sustaining and developing our world. Research conducted at Wal-Mart and reported in the book Strategy for Sustainability describes some interesting findings.16 The author interviewed Wal-Mart associates, exploring the basic concepts of sustainability and discussing what mattered to most of them. Here are some of the findings:

1. They believe the environment is in crisis. Once you removed the politics from the equation, people were ready to believe in global warming.

2. They want to learn more about it. Wal-Mart associates value learning, and any time they had the chance to learn something new that they could share, they were excited.

3. They want to do something about it. They lead busy lives with complex demands from family, work, religion, and hobbies. But if they could do something to help the environment that would also help them achieve their other goals, they were all for it.

4. They have not made sustainability their top priority. Sustainability does not work as another “thing” to care or worry about. But when the author presented sustainability as a framework that could help manage the other priorities in their lives, from personal health to finances, they were able to conceive of it as a matter of common sense.

Just as sustainability does not work for businesses unless it serves business needs first, sustainability does not engage individuals unless it first and foremost solves problems they experience in their lives.

The Chain of Impact for Green Projects

Sometimes it is helpful to think about the success of a green project in terms of a chain of impact that must occur if the project is going to be successful in terms of its business contribution. After all, if there is no business contribution, it is unlikely the project will be implemented. The chain of impact includes the five categories of data discussed in general terms previously. Together, these five levels form a chain of impact that occurs as projects are implemented.17 But this chain of impact begins with the inputs to the process. Inputs, referred to as “Level 0,” include the people involved in the project, how long it will take it to work, cost, resources, and efficiencies.

Obviously, these data are essential to move forward with a project, but they do not speak to the success of the project. It is through reaction, learning, and application of knowledge, skill, and information that a positive impact is made on business measures. Stakeholders realize how much impact is due to the project because a step occurs that will isolate the effects of the project from other influences. Impact measures are converted to money and compared to the cost to determine the ROI. In addition to these outcomes, intangible benefits are reported. Though they are not a new level of data, intangibles represent impact measures purposefully not converted to money and are always reported in addition to the monetary contribution of a project. Figure 12.4 represents this chain of impact that occurs through the implementation of green projects and key questions asked at each level.

Implications for Human Capital Strategy

Strong leadership is necessary for projects to work. Leaders must ensure that green projects and sustainability efforts are designed to achieve results rather than just to improve image. These projects and efforts must deliver the value that is needed by all stakeholders. Several actions must be taken to provide effective, results-based green leadership:

• Allocate appropriate resources for green projects and sustainability efforts.

• Assign responsibilities for green projects and programs, perhaps under the CHRO.

• Link green projects and programs to specific business needs.

• Create expectations for the projects’ success with all stakeholders involved, detailing their roles and responsibilities.

• Address the barriers to the successful project early on so that the barriers can be removed, minimized, or circumvented.

• Develop partnerships with key administrators, managers, and other principle participants who can make the project successful.

• Communicate project results to the appropriate stakeholders as often as necessary to focus on process improvement.