Force 4: Employee Engagement. Employee engagement is an issue that attracts a tremendous amount of management attention and many resources. The challenge is to make sure employees are actively engaged in their work so that productivity is enhanced, quality is increased, and they stay with the organization. This involves not only the nature of the work itself but the why of the work and the how of the work. This focuses on the different projects and processes designed to improve job engagement. It also involves where and when the work is accomplished. There is a trend toward more alternative work solutions, including allowing employees to work at home in many settings. There is also a push to allow employees to adjust their hours, so they determine when to complete their work. Finally, the design of the workspace makes a difference in employee performance. All these issues need to be addressed in the human capital strategy so that employee performance is maximized.

6

ENGAGE EMPLOYEES AT WORK

Changing the Nature of Work to Maximize Performance

There is probably no other topic more frequently discussed in the human resources area than employee engagement. Articles, conferences, and books are filled with issues about employee engagement, usually for good reason. Fully engaged employees will remain with their organization, produce more, have better quality, and be more efficient. In addition, they will satisfy customers and increase sales. This is achieved by examining not only the why, what, and how of the work but also where and when the work is done, addressing alternative and flexible work systems and workspace design. When these issues are addressed properly, they can foster a long-lasting, high-performing work team. This chapter explores a variety of issues about employee engagement, how to make it successful, and how to know when it is successful. It also discusses different arrangements for alternative and flexible work systems and how to make them work—all leading toward a particular set of strategies for these issues.

Opening Story: Quicken Loans

Quicken Loans is a banking and credit services company with $3.6 billion in annual revenue. Founded in 1985 in Detroit, Quicken Loans has nearly twelve thousand employees. At Quicken Loans, employee engagement is not a process, a department, or survey. Engagement is part of the business strategy and culture of this intentionally flat organization. Every employee (called a “team member”), from new hires to CEO Bill Emerson, is responsible for identifying problems and creating and implementing solutions, and team member engagement is evident from its twelfth-place ranking in Fortune’s 2015 list of the “100 Best Companies to Work For.”1

The Quicken Loans “ISMs” book is a physical embodiment of team member engagement at the company. ISMs are simple, easy-to-digest principles that form every business decision at Quicken Loans. The book has a pop-art look and details what is and is not accepted at Quicken Loans, a reminder of the lessons learned from day one: the expectations for empowered team members to not wait for a form or a process, to do what needs doing, fix what needs fixing, and call every customer back, every time, no excuses.

ISMs are written in simple and accessible language, and the ISMs book is updated continually. The spring 2015 edition includes this list:

• Always raising our level of awareness.

• The inches we need are everywhere around us.

• Responding with a sense of urgency is the ante to play.

• Every client. Every time. No exception. No excuses.

• Obsessed with finding a better way.

• Ignore the noise.

• It’s not about WHO is right, but WHAT is right.

• We are the “they.”

• You have to take the roast out of the oven.

• You will see it when you believe it.

• We will figure it out.

• Numbers and money follow, they do not lead.

• A penny saved is a penny.

• We eat our own dog food.

• Simplicity is genius.

• Innovation is rewarded. Execution is worshipped.

• Do the right thing.

• Every second counts.

• Yes before no.2

Employee onboarding is a cornerstone of the culture. Programs host 100 to 400 new team members at a time for an eight-hour session with CEO Bill Emerson and Chairman Dan Gilbert on the ISMs. The ISMs book is distributed, along with Emerson’s email address and phone number, to new team members.

All other talent management practices are based directly or indirectly on the ISMs, including career development, performance management, training and development, leadership development, and succession management.

There are no formal engagement surveys. Instead, leaders have regular sessions with their teams to ask what can be done to help them work more productively and be more satisfied with their work and the company.

The workspaces look deceptively whimsical. At first glance, for instance, the customer service area looks like colorful chaos. But the ceilings and dividers are functional, diluting background noise so each customer feels as if he or she is talking to a person, not a call center. The basement copy room, in which the main job is the logistics of shifting paper—a high-volume product for a mortgage company—is light and airy. The ceiling fixtures are playful representations of paper, and natural light is funneled from the street. Team members know that they are key parts of the “mortgage machine” that drives company profits, not just workers in the mundane world of paper supplies.

Elements of fun and functionality are integrated, promoting collaboration and teamwork and ensuring that safety and physical comfort are met so that team members can focus on clients. Venues for relaxation and leisure help team members regain focus. The company also offers team members free snacks, benefits such as pet insurance, and at the Detroit headquarters, on-site amenities from child care to Zumba classes. The philosophy is that while the company’s purpose is not popcorn and slushy frozen treat machines in the break room, those things help the company achieve its purpose, because giving team members both concierge service and a sense of fun quickly transfers to customer service. Team members know what customer service is because they receive it themselves.3

The Shifting Nature of Work

When you look into any kind of organization, you can see that the nature of work has changed. In some organizations, it has changed dramatically, particularly for knowledge workers in office spaces. This change in work involves the work itself, the meaning of work, and how it is accomplished, including the place, time, and environment in which it is accomplished. This shift is illustrated in Figure 6.1 as the drastic differences between employee behaviors of the past the future. Many of these changes focus on engagement, having an employee who is more connected to the organization, and that feeling of belonging and ownership translates into more effort, more productivity, and more success for both the individual and the organization. Many of the issues in this figure are described in this chapter, and some are captured in later chapters, such as the changes in technology.4 They all represent important opportunities for change and improvement, and they reflect excellent topics to be addressed in the human capital strategy.

|

Future |

|

|

Disengaged with work |

Engaged |

|

Keeps busy |

Gets results |

|

Finds satisfaction away from work |

Finds satisfaction at work |

|

Hoards information |

Shares information |

|

No ownership of work |

High levels of ownership |

|

Focuses on knowledge |

Focuses on adaptive learning |

|

Minimal collaboration |

High levels of collaboration |

|

Predefined work |

Customized work |

|

No voice |

Can be a leader |

|

Focuses on inputs |

Focuses on outcomes |

|

Works in a cube |

Works in a variety of open space formats |

|

Relies on email |

Relies on collaboration technologies |

|

Uses company equipment |

Uses many devices |

|

Works 8–5 |

Works anytime |

|

Works in the office |

Works anywhere |

Figure 6.1. The shifting nature of employees at work.

Source: Adapted from Jacob Morgan. The Future of Work: Attract New Talent, Build Better Leaders, and Create a Competitive Organization. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2014.

Employee Engagement Is the Critical Difference

We’ve seen the headlines from newspapers in the developed economies of the United States and Europe about anemic economic growth, massive layoffs, scarce job openings, and worker disillusionment due to the demise of the “employee contract.” For those still working, they often find a working environment characterized by company instability, frequent management turnover, reductions in health benefits, reduction or elimination of pension contributions, and high levels of stress that result from either the fear of losing a job or having to shoulder the burden of additional work left by departed coworkers. For those who do find a new job after long-term unemployment, they are often overqualified, underutilized, or hired at lower compensation levels because it is a buyer’s market. In rapidly growing, emerging markets, the abundance of low-skilled workers often means a booming economy built on the backs of laborers in modern-day sweatshops and factories, sometimes with disastrous workplace tragedies. Over the past few years in the hotter job markets (and tighter talent pools) in parts of Asia, many employees jump from one job to another in order to move quickly up their personal title and salary ladder with little commitment to a company, its customers, or its mission.

Against that backdrop, it’s hard to believe that any company, anywhere, has the kind of employee population that can make it successful, given the challenging economies, increasing pressures from new competitors, rising pace of technological change, increasing government regulation, and heightened geopolitical risk. Yet there are companies who outperform their industry peers even when so many of the products, services, structures, and challenges are surprisingly similar. These companies excel at a variety of business metrics from shareholder value, to operating margin, to workplace safety. They are more likely to be innovative. They have stronger employee value propositions to retain key employees and a compelling brand to attract new talent.

What makes this critical difference? Many would argue, as would we, that the difference is an engaged workforce, which consistently delivers superior performance, creates innovative products and solutions, and serves as brand ambassadors to both drive customer loyalty as well as attract great candidates. But how can companies stem the tide of worker malaise and distrust? What can companies do to drive high levels of employee engagement? How can organizations build a culture of engagement that fosters the kind of employee performance that can make the difference between survival and success? And even more important, how do they measure the impact so that they know whether they are successful?

The focus of this chapter is on employee engagement programs and initiatives at the organizational or business unit level. This begins with an examination of the macro level of employee engagement: what employee engagement is, the factors the drive (or hinder) engaged workforces, the evolution of the concept of engagement, the state of engagement and engagement practices today, and thoughts on building a culture of engagement.

The Drivers of Engagement

There is a great deal of alignment in numerous studies about the drivers (factors that have significant influence) of engagement, which usually reflect aspects of the business culture, relationships with supervisors, and workload. Among the more well-known assessments of engagement drivers are the following:

Towers Watson’s 2012 Global Workforce Study lists these five priority areas of focus and the behaviors and actions that matter to employees:

• Leadership (is effective at growing the business; shows sincere interest in employees’ well-being; behaves consistently with the organization’s core values; earns employees’ trust and confidence)

• Stress, balance, and workload (manageable stress levels at work; a healthy balance between work and personal life; enough employees in the group to do the job right; flexible work arrangements)

• Goals and objectives (employees understand the organization’s business goals, steps they need to take to reach those goals, and how their job contributes to achieving goals)

• Supervisors (assign tasks suitable to employees’ skills; act in ways consistent with their words; coach employees to improve performance; treat employees with respect)

• Organization’s image (highly regarded by the general public; displays honesty and integrity in business activities)5

The Merit Principles Survey, which is administered to more than thirty-six thousand workers by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, asks questions to elicit information about these drivers:

• Pride in one’s work or workplace

• Satisfaction with leadership

• Opportunity to perform well at work

• Satisfaction with recognition received

• Prospect for future personal and professional growth

• A positive work environment with some focus on teamwork6

Research from The Conference Board revealed these eight drivers of engagement to be key:

• Trust and integrity

• Nature of the job

• Line of sight between individual performance and company performance

• Career growth opportunities

• Pride about the company

• Coworkers/team members

• Employee development

• Personal relationship with one’s manager7

Drivers of engagement have been relatively consistent over time; however, there are now more frequent mentions of both recognition and the desire to do meaningful work (aligning with the mission of the organization).

Stages of Engagement

Engagement science has been evolving for some time, and it has already had a major impact in organizations in terms of what they do and their success. But there is a lot more potential for the future. It is through human capital strategy that additional efforts will be made in this important area. It is helpful to review the status of engagement through the stages of its development—first, with research pinpointing how it arrived and morphed into a powerful topic in almost every human resources function. Next, the status of engagement as a process and a practice is underscored. Finally, its impact, the value of engagement in terms of what is being reported now, is covered.

Research

From its humble origins as research about “employee motivation” in the mid-1950s, predominantly among companies in the United States, to “job satisfaction,” to “employee commitment,” and finally to the current concept of “employee engagement,” these attempts have sought to link worker attitudes to productivity with the belief (even in the absence of definitive proof) that engaged workers are more productive and valuable than those who are not.

Management theory, including the early work of Mary Parker Follett in the 1920s, has long sought to understand the ways in which organizational structure and management practice can impact employee behavior, resulting in improved business performance. In the 1950s and 1960s, researchers like Frederick Herzberg studied employee motivation and the elements of the workplace that drove either satisfaction or dissatisfaction, concluding that these elements are often very different things.8 Perhaps the most important pioneer in terms of engagement is Scott Myers, who integrated the research of many people, including Rensis Likert, Douglas McGregor, David McClelland, Abraham Maslow, Chris Argyris, and Fredrick Hertzberg. Combining all this research and making sense of it in terms of its implications for employees and their work, Myers published a book in 1970 to name and explain the concept he developed: Every Employee a Manager.9 In his work, Myers showed how each employee can and should manage their work to a certain extent, with some obvious limitations. For the most part, jobs can be managed by individuals so they feel ownership and responsibility for their work, the ultimate form of engagement. Myers was able to make it understandable and put it into practice as he worked with many executives, bringing this concept to job design and supervisory practices as well as human resources programs.

Job satisfaction surveys elicit information about the way employees feel about their work environment, compensation, company benefits, and management, among other aspects of their workplace. Examinations of the concept of job satisfaction began to appear in the academic literature in the mid-1960s, notably The Measure of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement: A Strategy for the Study of Attitudes.10

Rates of job satisfaction in the United States have suffered for a variety of reasons, including the erosion of employee loyalty in the 1980s when pension plans changed and off-shoring, layoffs, and plant closures shattered what had become an employee expectation of stable, long-term employment. As part of one of the longest-running examinations of job satisfaction in the United States, The Conference Board’s latest annual study reveals that less than half (47.3 percent) of U.S. workers say that they are satisfied with their jobs, compared to the 61.1 percent in 1987, the first year of analysis. This reflects a steady decline in job satisfaction over the decades, which only recently returned to pre–Great Recession levels after hitting its lowest point in 2010 at 42.6 percent.11 However, while these concepts are related, job satisfaction is not the same as engagement.

Academic research specifically regarding employee engagement began to appear in the early 1990s. Even then, research posited that engaged and disengaged workers offer varying degrees of “effort” and are, at various times, more or less committed to the work and the workplace, as explained in “Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work.”12 This more esoteric academic work continued to explore the ways in which employees feel (or fail to feel) connected to the workplace.

The 2002 Journal of Applied Psychology article “Business-Unit-Level Relationship between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis”13 was among the very first attempts to quantify engagement in terms of business results, and business leaders finally took notice, causing a dramatic shift in the level of attention paid to, and investments in, employee engagement.

Practice

Despite all the energy, effort, and resources (financial and otherwise) devoted to the issue of employee engagement for decades, the overall level of engagement in the workforce remains low and largely unchanged even in the face of the ongoing global recession. A research report called The State of the Global Workplace reveals that only 13 percent of workers are engaged, 63 percent are not engaged, and 24 percent are actively disengaged. There are, of course, regional differences, ranging from workers in East Asia (largely China) being among the least engaged, at 6 percent, to workers in New Zealand and Australia, where 24 percent of workers are engaged and only 16 percent are actively disengaged. The highest levels of active disengagement in the world can be found in the Middle East and North Africa.14 In the United States, among its nearly one hundred million full-time employees, 30 percent are engaged, 50 percent are not engaged, and 20 percent are actively disengaged.15

Engagement rates, of course, differ by region, country, and state; by occupation; by gender; by seniority level; by remote versus on-site location; by educational level; and by age. When organizations can determine levels of engagement on a granular level (by business unit or division, by employee population or team leader) then a clearer picture emerges from the data as to the relative performance of the groups against their peers. It is only when that data becomes actionable for the short term or even predictive for the long term that employee engagement data has any real value.

Among the most common issues that surface in employee engagement surveys are poor management/leadership, a lack of career opportunities or limited professional growth, a disconnect from the mission or strategy of the organization, a negative perception of the organization’s future, and an unmanageable workload.16

In 2012, The Conference Board surveyed engagement leaders at 209 companies in twenty-one countries to determine, among other things, what engagement practices, programs, and initiatives are most prevalent. Employee Engagement—What Works Now? reported these findings:

• The engagement function reports to the CHRO 52 percent of the time and to another senior HR executive 27 percent of the time, making this clearly a process still owned by human resources.

• Eighty-nine percent of surveyed human capital practitioners said that they have an engagement strategy in place.

• Fifty-two percent report that their organizations have been focused on engagement for more than five years.

• Sixty percent work with an external vendor and 16 percent work with a consulting firm to develop survey questions.

• Forty-one percent administer an annual survey and 27 percent administer one biannually, while 25 percent survey more frequently, leaving 7 percent who do not survey at all.

• Eighty-four percent indicated that their company’s approach to employee engagement strategy has changed in the last six to twenty-four months, either greatly (26 percent) or somewhat (58 percent), with many indicating that the change was a matter of “more focus” on engagement or increased accountability.

• Companies are using surveys to measure not only engagement but also leadership behaviors (66 percent), job satisfaction (63 percent), and organizational culture (60 percent).

• Only 49 percent of organizations link employee performance and results to engagement.

• Despite the importance of engagement, 48 percent said that they had no one dedicated full-time to engagement activities, and another 29 percent indicated that they had only one to three full-time employees dedicated to administering, monitoring, and analyzing these programs.17

Value

Employee engagement is critical to business performance and a success factor on many levels, from executing business strategy, to financial performance, to worker productivity, to the ability to create innovative products and services. In a recent annual study in which more than one thousand CEOs, presidents, and chairmen listed their most critical areas of concern for the coming year as well as the strategies they plan to use to address these challenges, it was revealed that, on a global basis, human capital issues are the top challenge, first- or second-ranked in every region, including China and India.18

Continuing its steady rise in the ranking of strategies to address the human capital challenge, “raise employee engagement” ranked second in 2014, up from third in the 2013 survey and eighth in the 2012 survey. In addition, respondents indicated the critical linkage between “Human Capital” and their next four challenges: “Customer Relationships,” “Innovation,” “Operational Excellence,” and “Corporate Brand and Reputation.” In fact, engagement is also a top-five strategy to address the challenges of Innovation and Operational Excellence. Respondents in this survey have clearly put employees at the center of everything.

One of the most comprehensive studies showing the business impact of employee engagement, The Relationship Between Engagement at Work and Organizational Outcomes, reveals that engagement is indeed related to the nine performance outcomes selected for the study, with consistent correlations across organizations. Among the other findings are the following:

• Business/work units scoring in the top half on employee engagement nearly double their odds of success compared with those in the bottom half.

• Those at the ninety-ninth percentile have four times the success rate as those at the first percentile.

• Median differences between top-quartile and bottom-quartile units were 10 percent in customer ratings, 22 percent in profitability, 21 percent in productivity, 25 percent in turnover (for high-turnover organizations), 65 percent in turnover (for low-turnover organizations), 48 percent in safety incidents, 28 percent in shrinkage (theft), 37 percent in absenteeism, 41 percent in patient safety incidents, and 41 percent in quality (defects).19

A longitudinal study of market performance, Employee Engagement and Earnings per Share: A Longitudinal Study of Organizational Performance During the Recession, reveals a correlation between earnings per share and employee engagement levels, finding that those organizations with the most engaged workers exceeded the earnings per share of their competition (even widening their lead during the recession) by 72 percent.20

These findings regarding superior earnings per share (EPS) are underscored in Gallup’s latest State of the Global Workplace, which states that engaged employees worldwide are almost more than twice as likely to report that their organizations are hiring (versus disengaged employees) and that “organizations with an average of 9.3 engaged workers for every actively disengaged employee in 2010–2011 experienced 147 percent higher EPS compared with their competition in 2011–2012. In contrast, those with an average of 2.6 engaged employees for every actively disengaged employee experienced 2 percent lower EPS compared with their competition during the same period.”21

The linkage between employee engagement and business metrics can also be found in Towers Watson’s Global Workforce Study:

• Higher levels of engagement can translate into higher operating margins, from just below 10 percent for companies with low “traditional” engagement levels, to just over 14 percent for those with high “traditional” engagement, to more than 27 percent for those with high “sustainable” engagement (defined by the “intensity” of employees’ connection to their organization based on three core elements: being engaged, feeling enabled, and feeling energized).

• Highly engaged workers have lower rates of “presenteeism” (lost productivity at work at only 7.6 days/year versus 14.1 days/year) and “absenteeism” than disengaged workers (at 3.2 days/year versus 4.2 days/year).

• Highly engaged workers are less likely to report an intention to leave their employers within the next two years (18 percent) versus the highly disengaged (40 percent), and 72 percent of the highly engaged also indicated that they would prefer to remain with their employer even if offered a comparable position elsewhere.22

A Watson Wyatt study, Using Continual Engagement to Drive Business Results, found “striking” differences in the performance of high-engagement workers and low-engagement workers: the highly engaged are 79 percent more likely to be top performers.23

Great Place to Work, a consulting and research firm, has studied engagement in the workplace for decades and includes trust as part of its model. Companies selected for inclusion on the “Great Places to Work” list, in partnership with Fortune magazine, exhibit a higher degree of trust and engagement in the workplace than other companies. Great Place to Work articulates these benefits of trust and engagement in the workplace:

• Committed and engaged employees who trust their management perform 20 percent better and are 87 percent less likely to leave an organization, resulting in easier employee and management recruitment, decreased training costs, and incalculable value in retained tenure equity.

• Analysts indicate that publicly traded companies on the “100 Best Companies to Work For” list consistently outperform major stock indices by 300 percent and have half the voluntary turnover rates of their competitors.24

We live in an age where maintaining an organization’s reputation and brand is a constant challenge, especially as organizations seek to retain current customers and attract new ones. Frontline employees are the key to success with customers. Numerous studies point to the importance of employee engagement on customer satisfaction, as listed in the Employee Engagement in a VUCA World report from The Conference Board. For example, research indicates that the customers of engaged employees use their products more, which leads to higher levels of customer satisfaction, and that these employees influence the behavior and attitudes of their customers, which drives profitability.25

The subject of a Harvard Business School case study and later author of a bestselling business book, Employees First, Customers Second, Vineet Nayar, had a then radical philosophy when he was vice chairman and CEO of India-based HCL Technologies: focus first on employees and make management accountable to them, as that will result in higher levels of engagement and effectiveness, making for stronger customer relationships.26

Engagement (or lack thereof) can also be measured in terms of economic impact with wide-ranging implications for countries and regions. While few employees are engaged and many more are not engaged, companies would do well to take action to mitigate the impact of the actively disengaged. Gallup estimates that economic loss from active disengagement costs the United States between $450 and $550 billion per year. In Germany, that figure ranges from €112 to €138 billion per year (US$151 to $186 billion). In the United Kingdom, actively disengaged employees cost the country between £52 and £70 billion (US$83 billion and $112 billion) per year.27

In addition to determining the impact on business performance, human capital programs and initiatives also rely on employee engagement data. According to a report by Bersin, 57 percent of HR practitioners indicated that the employee engagement metric was their most important in terms of determining talent management success.28

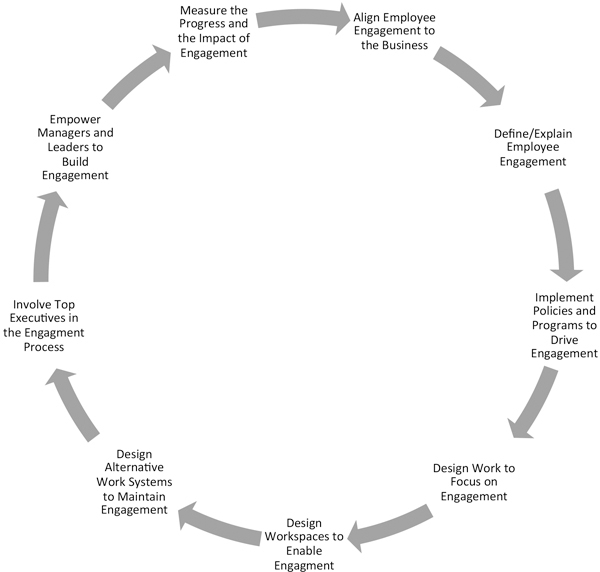

A Model for Implementation

It is helpful to understand engagement from the perspective of how it is introduced and implemented in an organization. The implementation usually follows several prescribed steps, and there are many different approaches offered in terms of how engagement is delivered. Using the focus on delivering value, we have adopted a model that brings engagement into the organization with a constant focus on the business contribution of the engagement process.

Figure 6.2 shows the nine-step engagement model covered in this chapter. As with most important processes, engagement starts with alignment to the business in the beginning and ends with measuring the impact on the business in a very logical, rational way. It is also presented in a cyclical fashion to show that this is a never-ending adjustment process, always collecting data to see how things are working and making adjustments when they are not. The next nine sections provide more detail on this model.

Align Employee Engagement to the Business

The beginning point with any process is alignment to the business, and engagement should be no different. Business needs and business value is the beginning point that executives want to see. This is expressed through classic measures in the system, usually reflecting output, quality, cost, and time. These critical data are reported throughout the system in scorecards, dashboards, key performance indicators, operating reports, and many other vehicles. A new HR program or human capital initiative should begin with the end in mind, focusing on one of those business measures, such as productivity, sales, customer satisfaction, employee retention, quality, cycle times, and so forth.

The challenge is to identify those measures that should change if employees are more actively engaged. The literature is full of hypotheses on these issues, all claiming a variety of results. This quick review can help management understand what might come out of this. The important point is that if a measure is identified, it is more likely that the engagement process will actually achieve its goal. Beginning with the end in mind is the best driver for the outcomes of the process.

Employee engagement scores, taken either annually or biannually, are impact data, because they indicate the collective impact of all the engagement processes in the organization. These data only describe perceptions, but they are still very important. Engagement, on its own, is an intangible measure in the scheme of impact measures. Unfortunately, many organizations early in the process stop there, merely reporting improvements in engagement scores. This leads many executives to respond, “So what?” So we have to do more, and doing more means that the results of engagement must be identified at the macro and micro levels.

The business impact is the linkage of engagement with certain outcome measures in the business category. The efforts of the HR team should be to illustrate the significant correlation and causation between improvements in engagement scores and outcome measures, which can typically be expressed in statements such as the following:

• Engagement drives productivity.

• Engagement drives quality.

• Engagement drives sales.

• Engagement drives retention.

• Engagement drives safety.

Others have developed more specific measures to link to engagement, such as processing times for loans to be underwritten, purchase cost for the procurement function, or security breaches in the IT function. The point is that engagement scores can be linked to many outcomes, and the HR function’s challenge is to show that.

Another way to show the business value of engagement is to connect it to individual projects. In this case, it is not just the overall engagement score that is linked to the business measures from a macro prospective but also an individual project involving individual participants. For example, a leadership development program for IAMGOLD, a large gold mining organization, was developed as a result of low engagement scores. After the program was implemented, which involved almost one thousand managers and cost the company $6 million, not only was the engagement score monitored for improvement, but individual measures that were selected by the participants were also linked directly to the leadership program.29 The leadership program actually challenged the first level of management to get employees more engaged and to focus their efforts on improving two measures that each participant supervisor in the program selected. As these measures changed, the effects of the program were isolated from other influences, converted to monetary value, and compared to the cost of the program. This yielded a 46 percent ROI in this important job group. In another example, a manufacturing plant used job engagement to improve quality of work, and the study tracking the success of the program examined improvements in quality, converted them to a monetary value, and then compared it to the cost of the program to yield a ROI of 399 percent.30

Define and Explain Employee Engagement

While there are many definitions of employee engagement, they are remarkably similar in their emphasis on several common elements. The following come from a review of engagement definitions found in Employee Engagement in a VUCA World:

• According to The Conference Board, “Employee engagement is a heightened emotional and intellectual connection that an employee has for his/her job, organization, manager, or co-workers that, in turn, influences him/her to apply additional discretionary effort to his/her work.”

• Towers Watson delineated employee engagement along three dimensions:

◦ Rational. How well employees understand their roles and responsibilities.

◦ Emotional. How much passion they bring to the work and their organizations.

◦ Motivational. How willing they are to invest discretionary effort to perform roles well.

• The independent, quasi-judicial agency in the executive branch of the U.S. government, the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, states, “Employee engagement is a heightened connection between employees and their work, their organization, or the people they work for or with.”

• According to management consultancy and executive search firm Korn Ferry, “Employee engagement is a mindset in which employees take personal stakeholder responsibility for the success of the organization and apply discretionary efforts aligned with its goals.”31

These definitions suggest both alignment with the organization as well as the willingness to expend discretionary effort as critical components of employee engagement. Further, the Gallup Organization delineates three types of employees as follows:

• Engaged employees work with passion and feel a profound connection to their company. They drive innovation and move the organization forward.

• Not-engaged employees are essentially “checked out.” They’re sleepwalking through their workday, putting time—but not energy or passion—into their work.

• Actively disengaged employees aren’t just unhappy at work; they’re busy acting out their unhappiness. Every day, these workers undermine what their engaged coworkers accomplish.32

Of note, one of the more recent developments in this space has been a focus on “well-being,” which links engagement to health issues as part of a movement toward holistic work environments. Another development is a focus on “happiness,” which seeks a holistic approach to worker contentment by weighing two components: overall life satisfaction and affect balance. (For an overview of this concept as well as profiles of examinations of happiness at Zappos, Google, HCL, Best Buy, and Southwest Airlines, please see The Happiness Premium: What Companies Should Know About Leveraging Happiness in the Workplace.)33

Executives must communicate not only what engagement means but how it affects them and how their role will change. This part of this step in the model is very critical, because it connects the executives to the process and fully explains what is involved. Some of this may involve stories that are told about what it means to be engaged. For example, there is the classic story of the janitor at NASA who was asked, “What is your job?” while he was sweeping the floors. He answered that he was helping put a man on the moon. Although this may appear to be an odd example, this is the kind of thinking and attitude that is sought through the engagement process. Stories, memos, meetings, speeches, and even formal documents can help define and explain the goal of the process.

Implement Policies and Programs to Drive Engagement

The next part of the process is to enact the different formal processes that will address the engagement issue.

The starting point is to show the mission, vision, and values of the organization. These are well-documented in most organizations, but the key is to integrate some language around engagement. For example, here is what Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos.com, says about engagement:

We have 10 core values, and when we hire people, we make sure they have similar values. For example, one of our values is to be humble. If someone comes in and is really egotistical, even if they are the greatest, most talented person technically and we know they could do a lot for our top or bottom line, we won’t hire them, because they are not a culture fit.34

After engagement is clearly defined and the dimensions of work that connect with the definition are clearly described, a survey is usually developed that secures the perception from employees. This is an initial survey to reveal the current status of engagement, and the survey data are used to make improvements. This is a classic survey-feedback-action loop that many organizations use as they survey employees, provide feedback to the survey respondents, and plan actions during the year to improve engagement. This is not only a routine, formal practice; it becomes the principal process improvement tool as changes and adjustments are made each year based on the engagement survey results.

Engagement is usually a principle component or determinate of a “Great Place to Work.” There are many Great Place to Work programs, ranging from the most well-known, Fortune’s “100 Best Companies to Work For,” to those of a particular professional field, locale, or specialty (such as diversity). For example, in Fortune’s “100 Best Companies to Work For,” two-thirds of the determinate for being on the list is the score of an engagement survey given to a randomly selected sample of employees. This is very powerful data, and a positive score is desired by the executive team as they build a great place to work. Being included on such a list helps attract and retain employees, and although the award itself is an intangible, it is obviously connected to tangible measures, as discussed earlier.

Among HR functions, specific adjustments can be made to improve various components of engagement. For example, recruiting and selection processes can include letting potential audiences know about the organization’s efforts to have employees fully engaged. Selection may be based on the desire of employees to be engaged in the organization, and more emphasis may be given to on-boarding as a process of aligning people with the philosophy of the organization.

The training and learning programs can be developed to reinforce the principles of engagement; even the method of learning is sometimes adjusted to be more adaptive to the individuals in organizations. Ideally, training is perceived as just in time, just enough, and just for me. That means it is customized for individuals and provided at the time they need it.

Compensation can be adjusted to reward individuals for being more engaged. Since engagement often leads to improved financial outcomes, sometimes this means paying for bonuses, as is particularly true for sales people. It also can be expanded into general recognition programs where individuals are rewarded for displaying proper engagement behaviors or managers and supervisors are rewarded for reinforcing them. In essence, any HR function that involves employees and influences employee behavior can have an important impact on engagement.

Design Work to Focus on Engagement

A huge part of this process is to make sure that the work inherently allows for engagement—for thinking and being empowered. It can be very frustrating for employees when they are asked to be more engaged but then they are still constrained by old job descriptions and structures.

Sometimes it is helpful to think about “where the work comes from.” Before work can be done, there are management functions that must be fulfilled:

• Planning—objectives, goals, strategies, programs, systems, policies, forecasts

• Organizing—staffing, budgets, equipment, materials, methods

• Leading—communicating, motivating, facilitating, delegating, mediating, counseling

• Controlling—auditing, measuring, evaluating, correcting

Traditionally, these functions are all centralized in a manager, supervisor, or designated leader, and work is prescribed for employees exactly, sometimes allowing no deviation from their job descriptions. But with an engagement perspective, employees are expected to get more involved in planning what work to do, when to do it, how goals and standards can be met, and maybe even how to source the information or materials needed. They may be involved in not only doing the job but controlling it, verifying the quality of the product, checking to see how procedures are working, making adjustments, and so forth.

This concept of empowerment is a vital part of engagement. Empowered employees take initiative and are held responsible for the things they do. They have ownership in the process, and thus they become fully engaged. Empowerment programs have been implemented for some time and have become an important part of driving the engagement process.

Design Workspaces to Enable Engagement

The workspaces of organizations have changed dramatically from private offices and cubicles to rotating desk assignments, couches, standing desks, treadmill desks, and even to no desks. One constant thing in the process is that offices have become more open. In fact, this openness has been evolving for many years. According to the International Facility Management Association, today more than 70 percent of employees work in an open-space environment, and the size of the workplace has shrunk from 225 square feet per employee in 2010 to 190 square feet in 2013. Work places are smaller and more open, and this leads to some concerns.

The first concern is the actual size of the office. Since it’s shrinking, does it provide enough space? This is a concern for individuals who often need space for all their accessories, devices, files, and work. This has led to some alternative configurations that provide this kind of space apart from the actual workspace.

Another concern is privacy. Privacy issues have changed over the years as workplace design has evolved. As shown in Figure 6.3, there has been a shifting need for privacy according to Steelcase, one of the largest makers of office systems. According to their research, in the 1980s there was a call for more privacy and less interaction, but by the 1990s there was a need for less privacy and more interaction. Now there has been another swing in the pendulum, and there is a call for more privacy and more interaction, but through interactive devices.35

|

1990s |

Now |

|

|

More privacy |

Less privacy |

More privacy |

|

Less interaction |

More interaction |

More interactive devices |

This leads to a concern for transparency in that now everyone has access to everything that everyone else is doing. In an open office, employees can see computer screens, hear conversations, read documents, and access all kinds of messages from different devices, making it perhaps too transparent for some. Because of this, there is a need to be less transparent.

Another concern is interruptions. Open offices invite people to interrupt frequently, as sometimes there is simply no way to shut the door in an open office. Managing interruptions can become a very difficult process. A similar concern is distraction within open offices. Hearing noises and seeing what is going on with other employees is a huge distraction to many people.

There are several major trends that have been occurring in workspace design. The first trend is to recognize the power of the open space environment, despite the concerns that arise from it. Figure 6.4 shows the relationship of space and performance.36 Assigned cubicles and private offices are certainly good for individual performance, but they are not helpful for group productivity where there is a need for collaboration that leads to innovation. An innovative organization is in the upper right-hand corner of the diagram, where offices are open and flexible and movement is possible between different offices, rooms, and activity areas. Collaboration is an important part of engagement, and it is also an important value for organizations trying to encourage high performance and innovation at the same time.37

Figure 6.4. Relationship of space and performance.

Source: Adapted from Ben Waber, Jennifer Magnolfi, and Greg Lindsey. “Work Spaces That Move People.” Harvard Business Review, October 2014.

Another important trend is that the space assigned to individuals depends on the time that they spend in the office. When people are using offices only a small part of the time, they will have a much smaller office. This is a departure from the traditional way in which office space has been allocated according to the title and rank of the employee. Executives who travel a lot may in some cases have a small office because they are not there very often. On the other hand, workers involved in major projects may need the extra space. Big, private offices are disappearing. They are too expensive and not necessarily functional, and problems are created when a person is unwilling to be a part of the social experiment of an open-space environment.

Common areas are developed, like conference rooms or meeting spaces at different places in an open environment, to give people ample opportunities to have discussions. Even little nooks can be set aside for people to meet quickly, reflect, communicate with a small team, or otherwise pull people together. Workspaces are also being designed to get people to interact. For example, Samsung recently unveiled plans for a new U.S. headquarters designed in stark contrast to its traditional buildings.38 Vast outdoor public spaces are sandwiched between floors, a configuration that executives hope will lure engineers and sales people into mingling. Likewise, Facebook will soon put several thousand of its employees into a single mile-long room. These companies know that a chance meeting with someone else in an office environment is a very important activity for collaboration.

A final trend is that workplaces are becoming more agile. They are not just for sitting anymore but also standing, walking, and moving. Research has shown that sitting at the computer all day is a very unhealthy practice, and many organizations are now trying to give employees the opportunity to get up often, move around, and in some cases even use a treadmill desk.39

Design Alternative Work Systems to Maintain Engagement

In the last decade, much progress has been made with alternative work systems, particularly in allowing employees to do their work at home. In this arrangement, actual employees (not contractors) perform work for their organization at home every day of the week. This enables a huge savings in real estate for the office, but there are many other benefits as well.

Several arrangements are available. The one that has perhaps the most impact is working completely at home. Under this arrangement, employees essentially do all their work in the home environment and make very infrequent trips to the office, if any at all. To accomplish this, the home office has to be configured as an efficient, safe, and healthy work place. This requires effort on the part of the organization to ensure, from a technology perspective, that the employee functions the same way he or she would in the office.

A second type of arrangement is office sharing, where one or more employees share an office. They predominantly work at home, additionally spending short periods of time in the office. In an ideal situation, two people share one office, but the schedule is arranged so that the two employees are not there at the same time.

A third option is hoteling, where several employees work at home but come into the office occasionally to do work as well. A suite of offices is available for them to use, and they have to make a reservation to use an office. This office space functions, essentially, as a hotel where employees check in and out of workspaces.

A fourth type of work arrangement is flex-time, where employees work sometimes at home, sometimes in the office, and set their own working hours as long as they work the prescribed number of hours. This often takes the form of a compressed work week, where employees may work three days with longer hours and then have an extra two days off. It could also mean working slightly longer hours each day to have a half-day off or coming to work early in the morning and leaving early in the afternoon.

Another option is job sharing, where two people are charged with doing one specific job. Each person works about half of the hours, and they coordinate their schedules so that they are not both there at the same time. Essentially, they are teaming up to get the job done but still working individually (each on a part-time basis).

Finally, there is part-time work, where individuals work reduced hours, receive limited benefits, and free up office space for others when they are not there. This allows employees the flexibility of having more time off while still remaining employed with the organization.

Whatever the arrangement, it has to be fully prescribed and have specific conditions and rules. The following box details the work-at-home program for a life and health insurance company called Family Mutual Insurance (FMI).

Benefits of Working at Home

There are many benefits derived from this type of program. First and foremost, this often leads to high levels of job satisfaction, as employees have the convenience of working at home and the personal savings of time and money from the elimination of their commute. This is particularly important for employees who have to drive long distances to go to work. These employees often come to work stressed, and their lengthy commutes may take many hours out of their day.

Job satisfaction often leads to retention. Some employees want to work in organizations where they have an opportunity to work at home, so this is a good way to attract employees and keep them. Most studies point to this flexibility leading to increased tenure.

Absenteeism is usually reduced with these arrangements. Sometimes employees need time to take care of personal errands and unexpected situations. With flexible arrangements, they can work those situations into their schedule. Of course, part of the rules are for them to ensure that they are completing all their work and working the numbers of hours required. Having a work-at-home situation may give them the flexibility they need to take care of emergencies or critical appointments so they do not have to take time off. Additionally, there is less sick time, because employees are not exposed to contagious illnesses that may come through an office or spread through public contact.

In offices where there is a high risk of accidents, these arrangements will eliminate those accidents. This is not a payoff for all organizations, but it is significant if there are hazards in the office where employees work.

Most studies show that employees are actually more productive when working at home. There are several explanations for this. The first is that they are less stressed and are more energized to do the work. Second, they often give a little more, because they are saving so much time from not commuting that they do not mind a little extra effort to make sure their performance is where it needs to be. Third, employees are sometimes concerned that their immediate manager may think they are not working a full eight hours a day, so they give more just to ensure that it does not become an issue. Fourth, there are often distractions at work that are avoided at home, such as frequent interruptions by coworkers, longer lunch periods, and unnecessary breaks. These productivity payoffs are observed in both businesses and governments. For example, one case study for the Internal Revenue Service showed improvements in productivity for examiners. Essentially, they could handle more cases working at home than they did in the office.

Eliminating the commute alone means there is much less stress with this arrangement. Due to stressful commutes, employees are often frazzled when they get to work, frazzled when they get home, or both. Working at home eliminates that kind of high-stress activity and often leads to a better work–life balance. Many people credit their work-at-home program for making their work–life balance acceptable.

However, the principle payoff for the organization is the savings in office space—but only if the office space is given up. Sometimes an organization will let an employee work at home but still keep an office for them. This is very inefficient, as the principle benefit is not realized. When an office space is given up, there is often a tremendous savings for an organization, even taking into account the costs of the modifications necessary to make the home office acceptable.

This arrangement also brings much applause from politicians and government agencies who are trying to ease traffic congestion in cities. Some major cities around the world have such congested streets that it takes employees three to four hours to make it to work and back each day. Thus some governments provide incentives for employers to let employees work at home. In the Netherlands, a proposed law gives the employee the right to work at home. The employer must prove that it will not work. Additionally, because automobiles are taken off the streets, there are fewer accidents and traffic incidents. Although it is not a dramatic reduction, it is certainly enough to add more monetary benefits to the ROI of working at home.

Finally, the most important benefit is the effect on the planet. Although this is not an immediate benefit for a company in terms of monetary savings, it is an intangible asset, and it is certainly a very tangible benefit for the environment, because for each automobile that is removed from the traffic flow, the actual tonnage of carbon emissions that are prevented from going into the atmosphere can be calculated. This is why so many environmental groups uphold working at home as a way of the future. Some environmental groups suggest that this is the single greatest action employers can take to help the environment. These benefits are huge, and when compared to the cost of the program, a very high ROI is delivered.

The FMI example represents a project that was measured all the way through to the financial ROI. In this case, 350 claims processors and claims examiners transitioned to working at home. Although their offices at home had to be equipped with the latest technology, including security software, so that they could effectively do at home what they were doing at the office, there was still a huge ROI. The payoffs included a reduction in office expenses by giving up the office space, reduced turnover, and increased productivity as more claims were processed at home than at the office. When this improvement was spread over one year and compared to the cost of the program, the savings generated a 299 percent ROI, with significant intangible benefits as well.41

Making It Work

Obviously, the use of home-office arrangements, although still growing, represents only a fraction of the total workforce. It is not always appropriate, and there are some rules that must be followed to make it work:

1. It should be voluntary. Forcing individuals to work at home usually will not be successful. Individuals must also be eligible. They must understand the terms and conditions, must want to pursue it, and must follow the rules.

2. The office must be designed properly for efficiency, effectiveness, and well-being.

3. There cannot be any distractions, including parental care for children or other types of concerns. For example, there can be no television in the room where the work is being done.

4. There must be certain transparency procedures (like logging in and logging out each day), guidelines regarding how to make up time when hours are missed, communication requirements, and so forth. Work rules must fit the specific organization and what is comfortable for the executives and management team.

5. Along with work rules comes the training that is needed to ensure compliance. Not all employees know how to work remotely, although they may be convinced that they do. There must be some assurance that they understand the ground rules and that they are willing to make them work in their situation.

6. Parallel with the training of the employees, the managers have to have training as well. They need to know how to work with employees remotely and how to adjust to not having a person always available there at the office.

7. There must be effective two-way communication so that there is regular reporting from the employee and regular follow-up with the manager. Good, clear communications are very critical.

8. Engagement must be maintained otherwise it could actually dip with a work-at-home arrangement. If employees are not around their support team, receiving constant feedback from their manager and coworkers, they might not feel as actively engaged.

9. Career aspects should be considered in the process. Remote employees cannot be left out of career development and career enhancement planning. They are often concerned that their career may suffer because they are not considered an integral part of the group.

10. Finally, all legal and compliance requirements must be followed. There must be no discrimination for this offering that would violate any of the regulations for equal employment opportunities and any other contractual or legal requirements.

Barriers

The reason that working at home has not become a widespread and common practice is that there are many barriers to these types of work arrangements. Perhaps the number-one barrier is resistance from the management group. Most managers follow the typical command-and-control model, and they want to see their employees regularly so that they can control their work. A lack of trust between managers and employees will also keep these arrangements from being effective. Managers have to trust employees to act in good faith and make it work.

Having remote employees makes some managers feel that they are less valuable to the organization. After all, if managers don’t have to be with the employees, see the employees, or meet with the employees, it might be assumed that the managers are not needed. This concern will have to be addressed so that managers fully understand the purpose of the arrangement and how they can manage employees remotely.

Another barrier is that it doesn’t work for every job, of course. Most jobs require a presence—in a factory, hotel, retail store, and restaurant. When a job requires employees to be at a particular place at a particular time, they will not be able to work at home.

This arrangement also doesn’t work for every employee. Almost everyone may want to take advantage of this arrangement, as it is a nice-sounding opportunity, but there are certain personalities that cannot function alone in an office setting. To work at home, a person has to be disciplined and work well without social interaction on a routine basis.

Furthermore, this working arrangement can be abused, and this keeps many organizations from making this move. Managers may worry that employees will say that they are working when they are actually not. Unless employee output can be easily measured and monitored, a working-at-home arrangement may not work. Although its potential has been proven in even creative jobs like those of graphic designers and editors, it is certainly more effective when managers can count standardized items such as processed claims or completed transactions.

Another barrier is that employees may worry about being out of sight and out of mind—that they may be forgotten and that their career advancement prospects will suffer because of it. There is also a fear that engagement may be reduced without the social interaction that comes from being in the same space as coworkers.

Finally, the biggest barrier is that it represents a significant change. Some executives like to measure the magnitude of their organization by the number of employees that they can actually see, the big buildings they occupy, and the large meetings that they can conduct. A remote workforce, no matter how vast, is not quite so visible.

Along with the barriers come the enablers, and there are many of them, as this section has already detailed. As evidenced by studies, there are many benefits of working at home for employees and for the organization. It is a good financial investment for an organization to pursue. Perhaps the most important benefit is the reduction in traffic congestion and environmental pollution. This is why this kind of arrangement is pushed by government agencies, environmental groups, and technology companies who indicate that they can now duplicate the work at the office in the home office. The technology is there, the reasons are there, and this should be an important consideration going forward.

Involve Top Executives in the Engagement Process

The role of top executives is very critical in any process, but particularly with engagement. With so much evidence that engagement adds value and so much potential for it to add more, most executives are willing to step up and commit resources, time, and effort to make sure that engagement works. This involves several areas:

1. Commitment. The first executive action is committing resources, staff, and other processes to make sure that engagement is properly developed, implemented, and supported in the organization.

2. Communication. Employees carefully weigh messages from the senior executive team, and what the team says about the engagement process sets the tone for others. It also shows the position of executives. Top executives should be involved in major announcements, the roll out of programs, and even progress assessments. When major actions are taken as a result of engagement input, top executives should be involved as well.

3. Involvement. Top executives must be involved in these programs. They should kick off programs and moderate town-hall meetings about engagement. They should participate in learning programs on preparing leaders and managers to build engagement in the organization.

4. Recognition. Top executives have to recognize those who are doing the best job. The best way to recognize exemplars of engagement is to promote them, reward them, and publicly recognize them. Engagement data should be placed alongside key operating results for this to be effective.

5. Support. Support is more than just providing resources and recognizing those who achieve results; it also means supporting the programs, encouraging people to be involved, and encouraging others to take action. This shows that leaders genuinely support these programs and their success.

6. Long-Term Thinking. Engagement cannot be seen as a fad that comes through the organization only to be abandoned for the next fad. Too often this occurs in organizations—executives work on “engagement” this year, and “lean thinking” the next year, and “open-book management” the next. The key is to stay with it and make it work.

7. Reference. Refer to engagement often, as a driver of gross productivity, a driver of sales, and a driver of profits. Making reference to engagement regularly in meetings, reports, press releases, and annual shareholder meetings brings the importance of the process into focus. Collectively, these efforts from top executives, which are often coordinated by the chief human resources officer, will make a difference in the success of the engagement effort.

Empower Managers and Leaders to Build Engagement

First-level managers are key in the organization. They are in the position to make or break engagement, and they have to be prepared for it. The first step is to conduct learning programs where the issue of engagement is discussed—how they can encourage it, support it, and build it in their work teams. This provides not only awareness of engagement but skill-building around the components of engagement to make the process successful in the organization.

Most important, first-level managers must understand why engagement makes a difference. They must become role models of engagement and take an active part in ensuring that employees are empowered, are involved in key decisions, and assume ownership and accountability for what they do. Managers must demonstrate what has to be done to make the engagement process work, and they must genuinely support it. They must reinforce the concept of engagement, reinforce what it means to them, and reinforce their roles in the process.

Much of this involves learning—learning what engagement is about and what makes it work but also learning what it can do for the organization. Position engagement as a process similar to sales training for a sales team, or production training for the production group, or IT training for the IT staff. This is an important process that managers must learn, apply, and use to drive results. This also means that they have to redefine success. Success is not just knowing something but making it work and have an impact. Making it work involves the behaviors that are exhibited as people collaborate to complete projects, but the impact must show up in improved measures of productivity, innovation, quality, and efficiency.

First-level managers are critical, as they must use all the tools generated around engagement. The HR team offers the many processes and tools to be implemented, but the frontline leaders can make the difference in the success of the process by using the tools appropriately, following up to make sure they work, and reporting issues and concerns back to the HR team.

Measure the Progress and Impact of Engagement

Measurement for this process involves several issues. The first one is measuring the progress with engagement through an annual survey. This assesses the actual perceptions of employees about the progress they are making. The annual survey must include several major elements to make it successful.

• It must be carefully planned, sometimes even with input from those who are being assessed.

• The data must be collected anonymously or confidentially. This is a time to collect candid feedback on the progress being made.

• The data must be reported back to the respondents quickly, so that they can see what the group has said locally and globally.

• There must be follow up, some immediately, some later—all in reference to the engagement program. This survey-feedback-action loop will ensure that the process is taken seriously.

Another measurement issue is linking the engagement scores to a variety of outcome measures such as productivity, sales, retention, quality, safety, and so on. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 14 and in other references. It is an important way for the organization, executives, and the HR team to see the value of this important process.

Success should also be measured in terms of individual projects, such as leadership communications, coaching, team building, management development, and leadership development. These are all programs that often involve parts of the engagement process. It is helpful to connect particular programs not only to engagement but to individual measures that may improve in this process. An example of this is a program involving managers at a retail fashion store where they were involved in a variety of leadership initiatives that also played into the engagement process.42

Finally, measuring ROI is the mandate for many top executives. If the CHRO can show executives the return on investing in engagement, it reinforces their commitment to make this process work, and it often improves not only their relationship with those involved in engagement but also their respect for the entire talent management and human resources function. Pushing at least some of the programs to the ROI level is very helpful, and ultimately it is possible to show the ROI of the entire engagement process. This is something that is covered amply in other resources.43

Implications for Human Capital Strategy

This chapter has highlighted the importance of engagement, which causes employees to become more involved in and committed to their work. Several elements affect employee engagement. The human capital strategy should consider these issues:

• The definition of engagement

• The role of engagement in the organization

• The organization’s structure and process to drive engagement

• Responsibility for the implementation of engagement

• The engagement implementation model

• The measurement strategy for engagement

• Workplace design to enable engagement

• Alternative work systems to maintain engagement