Predictive Management at Descon Engineering

Umair Majid and Ahmed Tahir

Descon Engineering Limited (DEL), a recognized multidimensional project management company operating in Pakistan and the Middle East, aims to become a world-class organization providing its customers with reliable and high-quality, yet economically viable, turnkey engineering and construction (E&C) solutions. DEL is part of the conglomerate named Descon, an association of legally independent companies integrated in a management relationship that operates under a common corporate identity, financial control, and ownership philosophy that is manifested in a distinct corporate culture. Descon, in its entirety, operates in engineering, chemical, trading, and power as its core businesses.

The service portfolio of DEL covers engineering, procurement, construction, maintenance, and manufacturing of process equipment for various sectors, including oil and gas, chemical, petrochemical, power, fertilizer, cement, and infrastructure. There are currently 5,000 management employees working with the company worldwide, and the company has seen exponential business growth in the last five years.

DEL is still moving up the value chain under the charismatic leadership of Abdul Razak Dawood, its founder. Once the managing director, he is now chairman of the conglomerate and is leading the company on its way to becoming world class.

Learning from the Past to Predict the Future

DEL now has a history that spans over thirty years, and during these years the company underwent various changes in strategy, structure, size, technology, workforce diversity, geographical locations, and business portfolio. Some of these changes were due to environmental factors and others were provoked by internal forces. The company also went through restructuring on various occasions. Major changes in the degree of centralization and decentralization were implemented three times. Each time, the organization learned new things, especially the ability to make proactive decisions and to achieve a balance between centralization and decentralization.

1986 Decentralization: The First Time

In 1986, DEL was a middle-size organization with a management staff of 300 and was operating in the domestic market. In fact, DEL was the leading Pakistani company in engineering and construction business. It had two major lines of business: construction (civil, mechanical, and electrical) and manufacturing. Each line had an executive director, and there was a managing director at the top. All staff functions, including human resources, finance, procurement, and store, were centralized. Though it was in the business of construction and manufacturing, the company did not have formal departments for handling quality assurance; quality control; or health, safety, and environment (HSE). Keeping his view of growing the business and foreseeing new projects, Dawood decided to delegate control.

Initially, the two functions of store and procurement were decentralized—that is, Construction would have its own Store and Procurement and Manufacturing would have its own. Much decision-making authority was passed down the line, aimed at increasing the efficiency of operations. It took just a couple of months to implement the decentralization because the change was made without a comprehensive environmental scan or a decentralization strategy. The resulting organization is shown in Figure 9.1.

However, within six months, Dawood realized that the change had been a mistake and that the time was not right for decentralization. The company began losing money, and the satisfaction level of its clients declined because of late completion of projects—a taboo in the project management industry. Dawood brought the centralized control back into place.

Figure 9.1. Store and Procurement as decentralized functions.

The reasons that the first decentralization failed were many. First, the decision regarding decentralization was based more on intuition and on perceptions of DEL’s management rather than coming from an objective analysis of prevailing business conditions and company strengths and weaknesses. Second, the managers at the top of both business lines were not competent enough to deal with the dynamics of delegation and empowerment. Third, proper systems and procedures were not in place, causing widespread manipulation of authority, and were left uncorrected because of unclear control mechanisms. Fourth, people who were in decision-making roles were not properly trained to handle such a change in structure.

Although the first attempt at decentralization was not a success, lessons learned would be applied to future planning. For instance, the company would need to be more predictive and analytical in any transformation, instead of just fixing current problems and acting in response to immediate events. Processes would have to be improved and written rules needed to clearly outline the limits of authority and the division of responsibilities. Most important, the company would have to develop leaders who could manage the expected future growth.

The company worked with the same centralized structure for more than a decade. However, during this time capable people were sought for senior positions. This planning enabled the organization to manage its growth and prepare for decentralization when the time would be right.

1997–1999 Decentralization: The Second Time

Because of favorable business conditions, especially for the construction sector, and because the company had a strong reputation in the region, DEL grew at a rapid rate in terms of business volume, profitability, size of the organization, market penetration, and geographical presence. A second attempt at decentralization was initiated in 1997, but this time the process was to be slow and careful.

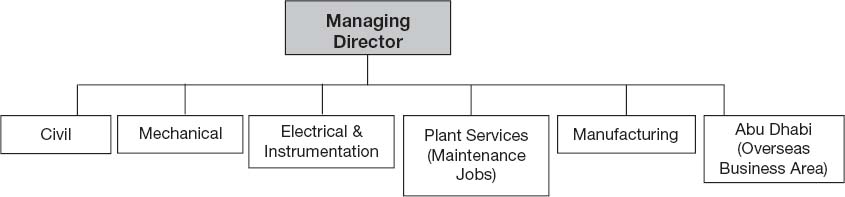

In November 1999, Abdul Razak Dawood joined the government of Pakistan as Minister of Commerce, Industries and Production, and so he handed over control of DEL to Mazhar Ud Din Ansari, who would serve as the new managing director. Dawood became chairman of the company. Additionally, DEL had lately established an overseas business unit in Abu Dhabi, so as to enter the Middle East market. The second decentralization involved six areas: Civil, Mechanical, Electrical and Instrumentation, Plant Services, Manufacturing, and Abu Dhabi, as shown in Figure 9.2.

Decentralization was more successful this time because of Management’s more predictive and proactive approach. Many of the lessons from 1986’s change effort were applied, which mitigated certain risks and avoided potential problems. The decentralization plan was put into operation only after a fair analysis of past problems, company capabilities, and environmental opportunities and threats. There were now experienced and capable people in senior positions to assume responsibilities.

In the early 2000s, management decided to diversify the business portfolio, a plan that laid the foundation for today’s Descon conglomerate. As part of this plan, the company established separate business areas in relation to the types of projects. For instance, a new business area named Infrastructure Projects Business Area (IPBA) was established to capture a share of Pakistan’s growing market for large-scale civil infrastructure projects. The Plant Construction and Services Business Area (PC&SBA) was established to acquire and execute plant construction and plant maintenance (shutdown) projects. The Manufacturing Business Area, which dated to the 1980s, was revitalized as the leading supplier of process equipment to operating companies, global EPC contractors and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) worldwide. (For definitions of business area and other relevant terms, see the following sidebar.)

Figure 9.2. Six decentralized areas with one overseas business unit.

A business area (BA) in Descon Engineering Limited (DEL) is a significant organizational segment or division within the overall corporate identity, and is distinguishable from other business areas in the company because it serves a defined external market where management can conduct strategic planning in relation to its projects. BAs are managed as self-contained units for which discrete business strategies (in line with the company’s overall strategy) are developed. BAs perform the line functions, are involved in core business processes of the company, and are aimed at generating revenue.

For example, at DEL, the Infrastructure Projects Business Area (IPBA) manages the mega civil-infrastructure projects like dams, barrages, and highways in the domestic market. The Plant Construction and Services Business Area (PC&S BA) covers a wide range of local plant construction and plant service projects. To cover plant construction and service projects in the Middle East, there are two major business areas: the Qatar Business Area (QBA) and the Abu Dhabi Business Area (UAE BA). The Descon Manufacturing Business Area (DMBA) provides project management services to its local and international clients in the area of process equipment manufacturing. To take care of turnkey projects, the Engineering Procurement Construction Business Area (EPC BA) has been established.

Business Support Department

A business support department (BSD) in DEL provides relevant support to the business areas—the line functions involved in core business processes of the company—to achieve their business goals. The nature of BSD work is advisory and supports the business organization, helping it work more efficiently and effectively. BSDs do not generate revenue; instead they are cost centers.

BSDs include Human Resource Development, Administration, Finance, Commercial, Business Development, Proposals Management, Information and Communication Technology, Quality Assurance/Quality Control, HSE (Health, Safety, Environment), and Contracts Management.

Joint Venture

A joint venture (JV) is an entity formed between Descon Engineering Limited and another company or organization to undertake business together in certain areas by capitalizing on the strengths of each other. Descon has, in total, four joint ventures: ODICO; JDC-Descon; Presson Descon International Limited (PDIL); and a training joint venture, TWI-Descon.

The company also expanded geographically at this time. After establishing its Abu Dhabi Business Area, it set up a new business area in Qatar. To complement its organizational expertise and facilitate its geographical presence in the world, the company entered joint ventures with three major organizations: Presson Enerflex (Canada), Olayan (Saudi Arabia), and JGC (Japan).

By virtue of its nature, a joint venture (JV) was operating as an autonomous body. The business areas were also autonomous to a great extent, though not fully independent of the head office. To support the core functions performed by these business areas, several staff functions (HR, Finance, Business Development, Proposals Management, and HSE) were formalized. Departments responsible for the staff functions were called BSDs (Business Support Departments)—Corporate. Looking at the business volume handled by each business area, management decided to decentralize the staff functions, too.

All did not go smoothly, however. Proper systems and procedures remained to be developed and people in leadership roles needed training to handle the affairs of this fast-growing organization. Also, future leaders needed to be identified and groomed from within the organization, as well as acquired from the job market, if the business were to continue to run efficiently and effectively.

In Abu Dhabi, business growth was too fast. DEL was awarded three major contracts, but the company lost a great deal of money on two of them and could only break even on the third one. The reason for this, according to the chairman, was that “the Finance and HR had weak control and that was because we did not have proper systems and procedures in place there. If you go for decentralization without having proper systems, you pay a price. And we paid a price.”

2007 Onward: Creating a Balance Between Centralization and Decentralization

When there were some major incidents in 2005–2006, the warning indicators started blinking and DEL’s management realized that something had gone wrong during the last decade that could prove to be fatal for the company.

In April 2007, when Shaikh Azhar Ali replaced Mazhar Ud Din Ansari as managing director of DEL, management started analyzing the situation. It didn’t take long to realize that it had overdecentralized. Corporate had lost the string with which to tie the centralized control to the decentralized units. That is, it had given too much decision-making freedom to the business area heads, which had created a huge power imbalance. In the head office, the right hand did not know what the left hand was doing. For example, the Abu Dhabi Business Area had built a fabulous state-of-the-art process equipment manufacturing facility with the name ADWORK, incurring a huge capital expenditure without the head office’s awareness. Even Corporate Finance, located at the head office, was unaware of it. There had been no approval from the head office and hence no approved budget. Corporate Finance didn’t have monthly or quarterly financial reports. Things were going from bad to worse.

When the situation was analyzed in detail, management discovered several gray areas of control. For example, there was no established Division of Responsibilities (DOR) to support the functionality of a decentralized structure. Each business area was operating primarily within its own silo, at its own pace, resulting in nonintegrated outcomes. Corporate did not have control over business areas, and there were no proper checks and balances. The senior management in the business areas and business support departments had never been trained to manage business in a decentralized structure. There was a leadership drought at the business area level. Although there was a system for succession planning, namely the Executive Vitality Dash Board (later named the Management Evaluation Scheme, or MES), it was not implemented across the company. There were also a number of flaws in the succession system, and hence it was not producing the desired results. Also, Finance and HR had no control because they lacked proper systems and procedures. Like the business areas, HR was operating in a silo, under pressure to perform and concentrate on daily HR operations, with little attention to future scenarios.

Predictive Management Is Instituted at DEL

The stage was set for another restructuring. There were many lessons learned from the past two attempts, and management was willing to go the extra mile to get everything right this time. Primary here, management would become far more predictive. As Chairman Abdul Razak Dawood said, “I want this company to be in the category of ‘built to last.’ ”

In July 2007, at a two-day forum for heads of Descon’s business areas, business support departments, and joint ventures, there was discussion of the future direction for the company. Shaikh Azhar outlined the plans to a group that included business heads he had appointed after he had taken the reins. A large number of these heads had been promoted from within, which was a positive sign for the future.

In October 2007, at another forum, Azhar detailed the road-map for Descon:

Organization design is to match organizational challenges. The management has decided to strengthen the business area organizations with the delegation of operational issues to operations managers. Business area heads are to focus on strategic planning, business development, HR, financial management, and systems implementations.

As we move on to a higher level [in the value chain], we need to restructure our organization accordingly in order to meet the challenges. The structure of the organization has been a challenge for us. This time the degree of centralization versus decentralization is being finalized with clear divisions of responsibilities for providing the proper interface between BAs and BSDs—that is, Corporate.

All policies are to be structured and developed at corporate level. All BAs have to follow corporate policies. No policy is to be developed at BA level. Corporate will audit BAs for compliance and implementation of corporate policies.

BSDs’ personnel seconded in the BAs are the extension of BSDs in the head office. Their selection, placement, and transfers are to be expedited by the BSD heads in consultation with the BA heads. Project Management Systems [a BSD for development and maintenance of the IT and project management systems across the company] will develop systems at corporate level and this process will be centralized. Policies at the BA level need to be standardized. Currently, every BA follows its own practices and policies. Each BSD will define its vision, mission, objectives, and Division of Responsibilities.

In the past, all financial limits and powers were vested in Corporate Finance. We shifted this authority and transferred all financial powers from Corporate Finance to BAs, without defining any financial control and system. It was a big mistake and we have borne its consequences. We thus need to maintain equilibrium between BAs and Corporate Finance. A financial manual will be developed and finalized that will outline the guidelines on financial limits and the degree of decision making.

“Descon” in the years to come is to be promoted as a brand in our entire group of companies. Historically, the word refers to Descon Engineering, but now the time has come to project “Descon” first, rather than “Descon Engineering.” There shall be more focus on transforming the company from an undisciplined organization to a disciplined and well-integrated one, working under one philosophy outlined by the head office.

At this point (in February 2008), Dr. Jac Fitz-enz—a pioneer and leading authority in the field of human capital measurement and predictability—was invited to assist the transformation by introducing the predictive management model and principles to DEL’s senior management staff. A two-day training session, attended by the leading members of management at DEL, provided a platform for diagnosing the organization’s strategic requirements and determining how predictability and human capital management initiatives could position the company on the way to becoming world class.

The session started with an analysis of external environmental forces (markets, competition, economy, business opportunities, globalization, technology, customers, suppliers, etc.) and internal factors (vision, brand, culture, systems, competencies, etc.). Responses on pre-training strategy questionnaires distributed to training participants, results of the environmental analyses, and the year’s workforce intelligence report (WIR) provided the basis for an organizational review to identify areas where DEL needed realignment to sustain its competitive edge. Various approaches for workforce planning and evaluation of HR processes were discussed. Participants identified the missing links among functions of HR, establishing these missing as the major reason HR services had not been properly integrated. Finally, through predictive analysis, the group pinpointed various areas for improvement, named the major development initiatives, and formulated a customized strategic framework to implement the new model, HCM:21.

The Implementation of HCM:21

The Human Resources Development (HRD) function in the company was considered to be a weak BSD. To strengthen this function and transform its role from an operational department to a strategic business partner, Tahir Malik had earlier become head of HRD. Now, following the session with Dr. Fitz-enz, he realized he faced many challenges:

![]() HR costs were rising, owing to a boom in construction and a burgeoning real estate sector in the Middle East.

HR costs were rising, owing to a boom in construction and a burgeoning real estate sector in the Middle East.

![]() Many other players were coming into the market, paying employees unsustainably high salaries, which DEL could not offer at the moment. Indeed, DEL was finding it difficult to attract star employees.

Many other players were coming into the market, paying employees unsustainably high salaries, which DEL could not offer at the moment. Indeed, DEL was finding it difficult to attract star employees.

![]() No career-growth paths and promotion criteria were defined, and as a result retention of key performers was proving to be a big challenge. There was no proper succession-planning process. Although a management evaluation scheme (MES) was available, it had never been implemented across the company and also had some flaws.

No career-growth paths and promotion criteria were defined, and as a result retention of key performers was proving to be a big challenge. There was no proper succession-planning process. Although a management evaluation scheme (MES) was available, it had never been implemented across the company and also had some flaws.

![]() As most of the heads were new in their roles, they needed to acquire necessary general management skills in the shortest possible time. Yet, Descon hadn’t focused on management training, and as a result it had incompetent people in top positions.

As most of the heads were new in their roles, they needed to acquire necessary general management skills in the shortest possible time. Yet, Descon hadn’t focused on management training, and as a result it had incompetent people in top positions.

![]() There was a drought in leadership at the middle level.

There was a drought in leadership at the middle level.

![]() A proper employee training and development system was lacking.

A proper employee training and development system was lacking.

![]() Employee remuneration and benefits were not competitive, and they were inconsistent and not equally applied.

Employee remuneration and benefits were not competitive, and they were inconsistent and not equally applied.

![]() Perceptions in the organization about Descon’s brand were inconsistent with those in the marketplace; a proper strategy for brand imaging and its communication was not available.

Perceptions in the organization about Descon’s brand were inconsistent with those in the marketplace; a proper strategy for brand imaging and its communication was not available.

It was time to take a big leap forward—to implement HCM:21 in its true spirit. This model would transform HR from an administrative role to a strategic business partner. To begin, Tahir Malik started strengthening his team. The subfunctions of Corporate HRD were reorganized into Recruitment and Selection (R&S), Training and Development (T&D), Compensation and Benefits (C&B), and the newly incorporated function of Organizational Development. To carry out the change process in an appropriate and timely manner, Malik assigned responsibilities and ownership to relevant HR functional teams. Also, he established a DOR for defining the work relationship between Corporate HRD and the individual BAs’ HR (called HRM, owing to its operational role) to ensure delivery of HR services efficiently and effectively.

With the vision of becoming the employer of choice, Malik instituted a number of initiatives to implement HCM:21.

Hiring Strategy Revitalization

In the past, the hiring strategy was reactive, and people were hired without linking the closure (demobilization) of existing projects with the initiation (mobilization) of new ones—that is, there was no comprehensive workforce induction planning in relation to future business requirements. The new and revitalized hiring strategy aimed at ensuring the preparation of a workforce induction plan so that hiring would be done only to match well-planned and approved organization charts.

Although promoting staff from within to fill higher and mission-critical positions was the priority, management also decided to hire “the best and the brightest” from the job market for positions that could not be filled from within; this would introduce best practices and bring new ideas into the company, hence challenging the status quo.

To cope with the shortage of talent, the Recruitment and Selection team explored new markets, including Southeastern Asian countries (Malaysia, Philippines, Korea, Indonesia, and Vietnam), Eastern European countries (Romania, Czech Republic, Poland, and Ukraine), Central Asian states (Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan), and South Africa.

The range of appropriate recruitment sources was also widened, to include career Web portals, local and international headhunters, job advertisements in local and international magazines and newspapers, liaisons with top-notch universities and institutions for on-campus hiring, internal manpower data banks, employee referrals, and coordination with Descon’s associated companies for cross-placement of human resources.

Establishment of a Training and Development System

The Training and Development function had not been carried out in any true sense of the term. Trainings were conducted in a haphazard way, usually on the recommendations of line managers. There was no system in place for identifying and analyzing the training needs of employees. As part of HCM:21’s implementation, a proper Training and Development system was set up. Ten training processes were established, detailing roles and responsibilities, entry criteria, inputs, tasks, outputs, exit criteria, integration, and general guidelines. These processes included a training needs analysis, development of a training plan, trainers’/training institutes’ assessment (pre-training) and selection, curriculum design and course customization, creation of or acquisition of training products, training program administration and logistical operations, informal training and other modes of employee learning and development, training effectiveness measurement, training material and data management, and training process improvement.

The Employee Development Programs

In relation to training and development needs, two comprehensive management development programs (MDPs) were designed. The first, MDP-1, was for junior managers, with the goal of enhancing their general management and administrative skills. The second, MDP-2, was for middle and senior managers, with the aim of enhancing their capacity of team-building, leadership, delegation, and change management.

For heads and top executives, an executive development program (EDP) consisting of various strategic courses was developed.

The Hire, Train, Develop, and Retain Program

An attempt at HR integration, the Hire, Train, Develop, and Retain Program (HTDRP), was developed with the aim of identifying top talent from a diverse group of quality universities and institutes (both local and international), then orienting and training these individuals in the company’s business processes and systems, developing and updating a competitive remuneration package, and making and implementing a viable retention strategy for retaining this talent. The program was an integrated framework that combined the efforts of all functional areas of HRD.

As a result, well-planned batches of fresh graduates were hired and trained, both at the company level and at the BA level. Major training programs administered under HTDRP included the Graduate Engineers Training Program (company level), Certified QA/QC Engineers (company level), Certified HSE Engineers (company level), and Project Engineers Leadership Program (BA level, for strengthening the EPC business area).

The In-House Faculty Development Program

This corporate-level program was designed to build the organizational capacity for administering in-house training programs designed and delivered by in-house trainers—that is, Descon employees. There were certain training programs that could only be designed (or customized), delivered, and evaluated by in-house trainers—for instance, programs based on Descon’s business processes, project management systems trainings, and in-house knowledge-sharing sessions. Also, for a large organization like Descon Engineering Limited, conducting trainings in-house, by internal trainers, was usually cost-effective. The in-house trainers covered topics ranging from project management, general management, and interpersonal skills, to application area trainings and project environmental issues. The train-the-trainer programs were conducted to identify and groom potential in-house trainers.

Analysis of Organizational Climate, Culture, and Attitudes

To study employees’ opinions on the quality of their work climate, and for identifying areas for improvement, the Organizational Development function designed a climate survey. The results were compiled and presented to management, and various recommendations that ensued included revising HR policies and procedures. Also, a number of employee motivation and engagement initiatives were taken—for example, the Descon family gala, Descon annual dinner, employee sports programs, Outward Bound team-building programs, and the Descon Lounge (a monthly in-house publication for employee participation).

Salary Surveys and Pay Restructuring

Because of a highly diversified business portfolio and an overdecentralized business past, there was inconsistency in pay structures across the company. To bring internal equity and justice in compensation and benefits, the company hired a third party to distribute salary surveys and conduct informal salary reviews. The existing pay structure was revised, with careful consideration of internal and external factors. Indeed, this was one of the biggest HR achievements, as it provided the baseline for employee retention.

Branding Communications

Any communications problems concerning branding had long been ignored. To correct this situation, a proper strategy for both brand imaging and its communication was developed. Some salient features of DEL’s branding communication strategy included:

![]() Centralization of brand management, and establishment of one consistent policy across the company.

Centralization of brand management, and establishment of one consistent policy across the company.

![]() Standardization of the company’s positioning statements, logos, taglines, etc. For example, the company’s positioning statement with respect to customer services was “Partners in Progress”; with respect to HR, the tagline was “Becoming the Employer of Choice.”

Standardization of the company’s positioning statements, logos, taglines, etc. For example, the company’s positioning statement with respect to customer services was “Partners in Progress”; with respect to HR, the tagline was “Becoming the Employer of Choice.”

![]() Preparation of a Descon Brand Book for providing standard branding communication guidelines in the company.

Preparation of a Descon Brand Book for providing standard branding communication guidelines in the company.

![]() In-house brand awareness sessions held to bring consistency to brand perceptions both inside and outside the organization.

In-house brand awareness sessions held to bring consistency to brand perceptions both inside and outside the organization.

![]() New employees onboarded regarding branding—making Descon brand awareness an essential part of their orientation.

New employees onboarded regarding branding—making Descon brand awareness an essential part of their orientation.

![]() Encouraging continual thought for future branding opportunities.

Encouraging continual thought for future branding opportunities.

Use of HR Metrics

Although HR metrics related to all the functional areas had been developed in the past, they were never implemented with a result-oriented approach. The training session on Descon human capital management, however, proved helpful in revamping and implementing HR metrics. These metrics included:

HR expense percentage

External cost per hire

Internal cost per hire

External time to fill

Internal time to fill

Cost per trainee

Employee trained percentage

Training cost per hour

Internal training hours percentage

External training hours percentage

Compensation expense percentage

Compensation factor

Separation rate

Most important, impact data against these and other HR metrics were collected and analyzed on a regular basis, and reports were generated. The implications and patterns identified in the reports helped HR revise and develop new HR strategies and policies.

Implementation of Enterprise Resource Planning

To manage the growth of the company and provide a centralized control mechanism, management conducted a preliminary investigation (an initial feasibility study) for implementation of an enterprise resource plan (ERP). Then, management contracted one of the most reputable ERP solution providers to integrate the systems, not only within HR but also to connect HR with other functions and systems in the company.

The Management Evaluation Scheme

The biggest challenge for Tahir Malik was to give the company a proper succession-planning process. He decided to improve on the existing management evaluation scheme (MES) and implement it throughout the company.

The main objective of the MES is to enable the company to maintain the team that can lead it and its BAs to superior performance, in terms of both quality and quantity, by providing an effective and continuous supply of human resources. Company chairman Abdul Razak Dawood, during his address to the Descon HR Forum 2008, highlighted the importance of MES for the company:

Why is MES important? [The real question is] Do we have leaders who will take the corporation to a much higher level than where it is today and who will take care of the company? MES is the only hope. That is why it is important. We must have a hundred people we can look to in order to choose leaders for tomorrow who will be leading our engineering, power, and chemical businesses.

The matter is worrisome. It is top management’s responsibility to identify the future leaders for the company and groom them. HRD will have to play a key role. For example, have you [HR people] evaluated a person properly before selecting him? Suppose we have to choose a horse to send to the Derby race in England. We will properly assess and evaluate the horse. Now, that’s only a horse. But [in our case] it’s the human being—God’s creation with all the complexities. If you include a person in the bench strength [for MES] who shouldn’t be there, or miss a person from bench strength who should be included, you are not being fair to the company. It’s not easy to evaluate people, HR! It’s your job to evaluate. Similarly, what you hear throughout the year about your employee—his strengths and weaknesses—[you should] note it down and put it in his file, so that when the evaluation time comes, this information can help.

The whole process of MES was revised and standardized. A career anchor questionnaire, level identification criteria, and succession-planning criteria were developed. A benchmark was set to categorize employees in five different levels according to their performance and potential for growth:

![]() Level I: High Potential–High Performance. Ready now to take the higher position.

Level I: High Potential–High Performance. Ready now to take the higher position.

![]() Level II: High Potential–High Performance. Shall be ready in two to three years to take the higher position.

Level II: High Potential–High Performance. Shall be ready in two to three years to take the higher position.

![]() Level III: Fit for Purpose. Understands and performs his or her job very well, but can’t take the higher responsibility.

Level III: Fit for Purpose. Understands and performs his or her job very well, but can’t take the higher responsibility.

![]() Level IV: Concerns. Performance seldom meets expectations; appropriate training and guidance are required.

Level IV: Concerns. Performance seldom meets expectations; appropriate training and guidance are required.

![]() Level V: Exit. Lack of commitment, no potential for improvement, and therefore notice of intent to separate would be required.

Level V: Exit. Lack of commitment, no potential for improvement, and therefore notice of intent to separate would be required.

The objectives in categorizing the employees in these levels were to let the employees know where they stood vis-à-vis other employees and how the company ranked them; to develop career paths for Level I and II employees, which would develop them into future leaders; to enable the company to determine appropriate programs for employee development, with special focus on successor development; and to ensure focus on succession planning at all the levels.

After putting everything in place, in July 2008, the MES was implemented organization-wide. Management was clear about its taking some time to mature and produce what Descon needed. And after this successful implementation, management had the names of individuals who were the High Potentials and a means for developing their talent so they could assume leadership roles in the future. Every BA and BSD had its succession plan for mission-critical positions along with the bench strength. By integrating all the BA and BSD succession plans, corporate management had a company-wide succession plan. The gray areas—where there was a leadership drought—were identified and strategies were formulated to water those areas.

When MES 2009 was initiated, the last year’s MES review was conducted. The review revealed that 30 percent of the career moves (planned in 2008) were successfully implemented. About 80 percent of the MES-based training needs had been addressed. Most of the mission-critical positions, like project managers, construction managers, planning managers, and process engineers, had been filled with the successors identified through MES.

MES 2009 was an improved version of the original scheme, and it was also implemented in two of Descon’s joint ventures: JGC-Descon and Presson Descon International Limited. More important, the MES for BSD staff residing in the BAs was consolidated and presented to the managing director by the respective BSD heads. This was an encouraging example of process ownership and the BSD heads’ onboarding with an HR process.

The Way Forward

Implementation of the HCM:21 model has helped DEL position itself on the track toward world-class engineering, manufacturing, and construction. However, the journey has just started, and the desired outcomes of these initiatives are only just emerging. According to Chairman Abdul Razak Dawood:

Things are getting better now. [For instance] MES is better than what it was last year. In 2010, it will be much better than what it is today. Rotation policy is about to be fully implemented. To me, the most important thing is “to put the company in a position where it can become world class.” We need to go further; we need to improve the systems; and for that, we don’t want our people to become complacent, because the road to success is always under repair.

If the next chairman, managing director, and BA and BSD heads are no better than the existing ones, we have not done our job. A few days back, I sent an e-mail to my executives that, in Vietnam, a wonderful business opportunity was emerging. But I asked them to forget about it because I didn’t think we were ready to take it on. The good news is, we are not growing too fast. So we have time to get ready.