4

Managing Without Authority

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• Identify your dependence on those around you, and their dependence on you.

• Describe how you can increase your influence in the organization.

• Describe the importance of persuasion as a management tool.

• Describe the four elements that are the foundation of persuasion.

Many new managers believe that organizational authority is all they need to get things done. This is far from true. In the contemporary workplace, authority usually counts for far less than the ability to influence and to persuade others. Even people with tremendous organizational power discover that their power does not give them a free hand in getting things done; they find that they are dependent on the good will, support, and collaboration of others—including their subordinates.

Today’s managers frequently find themselves in situations in which they have no organizational authority, but must get things done. Consider the following real-life situation:

Sal is a mid-level manager in the marketing department of Quasartech, Inc., a young, fast-growing Internet company. Its “product” is its website search engine, which makes it possible for users to locate and gather information on small businesses throughout the United States that happen to be for sale. Its goal is to build and operate a site that will help anyone interested in purchasing an existing small business to (1) locate businesses for sale and (2) find information that will help them determine if they want to investigate further. The company makes money by selling ad space on the site.

Sal’s boss has asked him to be the leader of a cross-functional team of employees whose goal would be to develop one aspect of the company’s website. “We need to get more for-sale listings on the site,” he explained. “The more listings we have, the more people will be drawn to our site—and to the advertising that pays the bills around here.”

Sal accepted the assignment, and after some thought and discussion with others, drew up a list of people whose skills and experiences would contribute to the success of his venture—the manager of the client relations group, one of his peers in marketing, two people from the software engineering group, and one salesperson. He determined that each person would spend two hours in meetings and five hours in assigned tasks each week. He then went to the managers of those individuals and asked if they could spare those people for the equivalent of a day each week for the next two months. With their consent, Sal recruited the people he needed.

Unlike his direct subordinates, Sal had no authority over the people on the team. They didn’t report to him, and Sal wasn’t in a position to provide them with promotions, salary increases, or bonuses. He could not fire or even discipline them. If he ordered anyone to do anything, that person could correctly reply, “I don’t work for you, Sal.” One team member, the client relations manager, actually enjoyed higher organizational rank than Sal.

In order to succeed in the situation just described, Sal had to motivate people to work together toward a common goal, and give it their best effort. If Sal relied exclusively on his organizational authority as a manager, he would never be successful in getting his team members to satisfactorily complete their task.

In today’s team-oriented business culture, situations like Sal’s are common, and managers must learn to accomplish their goals without benefit of formal authority. But these are not the only situations in which managing without authority is necessary. People like Sal—and like you—must enlist the support and collaboration of peers and of people who outrank them. They must also deal with subordinates who respect and respond to qualities other than formal authority. But what can a manager do in these situations? This chapter will explain two concepts for managing when formal authority is absent or not effective: influence and persuasion. But first, let’s consider organizational dependency, a concept that explains why the power of formal authority is so limited.

DEPENDENCIES

Most employees depend on their bosses for all kinds of important things: pay raises, protection from other powerful managers—even their jobs. This sense of dependence is based on long-established notions about people with authority being in a dominant position relative to their employees, who are in subservient, dependent positions. The dominance-dependence relationship can be found throughout human history. The feudal system of the European Middle Ages, for example, was characterized by a dominant ruling class and a subservient peasantry that worked the land owned by the masters. However, even in this situation, dependency was a two-way street. The serfs depended on their feudal masters for military protection from invaders, for justice, and for order; the masters, in turn, depended on their serfs to produce the crops on which their wealth and privileges depended and to serve as foot soldiers in war. Though the scales were tipped in favor of the ruling class, masters and serfs nevertheless depended on each other.

We observe a similar two-way street in organizational life: employees are dependent on their bosses, but those bosses—despite their authority—depend on the energy, efforts, and know-how of their subordinates. And, just as in the feudal system where the barons depended on one another for trade and mutual defense, managers participate in a complex network of interdependencies with their peers in other departments, people of higher or lower rank throughout the organization, and outside contacts such as vendors and customers. Managers who recognize their dependence on others are less inclined to command, to order, or to threaten those who work for them, or to pull rank in cross-departmental disagreements. They understand the limited utility of their formal authority and seek out other ways of getting things done through people. They value the greater power of influence and persuasion, and they work to develop these skills.

Exercise 4-1

Exercise 4-1

What Are Your Dependencies?

Who do you depend on to accomplish your assigned goals? Name two people in a different department whom you rely on. Why do you think these individuals are willing to assist you?

INFLUENCE

Recognition of one’s dependencies is a first step in managing without authority. That recognition clarifies the need to enlist the collaboration of others in achieving organizational goals. Successful managers enlist collaboration through the application of personal influence, which we define as a person’s ability to alter the behavior of others without recourse to the power to command. If we think about it, each of us can trace some aspects of our behavior to the influence of others. We may work late on some days, not because we were ordered to do so, but because our work team expects a task to be completed by the next morning. We may take up some civic cause because of the influence of a neighbor whom we admire.

Influence is present in many situations, from the settlement of disputes to the assignment of a plum project. We see many similar situations in the workplace. Consider this example:

Helen, a powerful executive, is pushing to establish a branch office in Winnipeg, Canada. Mike, the VP of Sales, thinks the numbers supporting the proposal are a little weak, but he has decided not to oppose the plan. “Helen’s intuition has been right before—the Manitoba office has been a big success. And Helen has the CEO’s ear on a lot of issues that affect me and the sales force,” Mike tells himself. “I can live with the Winnipeg office, and I need Helen as a partner, not an adversary.”

Power often lurks in the background of influence. As President Theodore Roosevelt famously said, “Speak softly, but carry a big stick.” The power hidden behind softly spoken words can influence others to take a particular course of action. For example, you may use influencing tactics to get an employee to take on a new assignment—by explaining how it will benefit her career development, or by appealing to her team spirit—but the fact remains that you are her boss and could conceivably order her to take the assignment.

Increasing Influence

Because of its usefulness as a tool for managing without authority, a manager should actively take steps to increase his or her influence in the organization. Aside from gaining influence by gathering more organizational power, there are several ways to do this. It’s useful to think of influence as based on personal attributes including trustworthiness, reliability, and assertiveness. Cultivating these attributes will not in itself increase your influence, but without them, you cannot be influential.

Trustworthiness

Trust is a condition that gives us confidence in the character, ability, or truthfulness of someone else. In a business context, trust is something that’s earned over time by:

• Telling the truth, no matter now painful.

• Delivering both the good news and the bad.

• Taking responsibility for our mistakes.

• Identifying the upside and downside potential of our suggestions.

• Recognizing the value of ideas that compete with our own.

• Giving careful thought and analysis to our proposals.

• Providing decision makers with the information they need to make wise choices.

• Putting organizational goals above our own.

• Respecting confidentiality.

• Having the courage to say “I don’t know” when appropriate.

Reliability

In the workplace, reliability is a personal quality that gives others confidence in saying or thinking, “I can count on that person to follow through.” Not everyone has a reputation for reliability; those who lack it have little ability to influence others.

Like trust, a reputation for reliability is developed over time. Start developing yours today by:

• Never making promises you cannot or will not keep.

• Remembering that decisions are ineffective in the absence of implementation (follow-through).

• Not giving up when you encounter impediments.

• Keeping all your agreements, large and small (this includes being on time for appointments and meetings).

• Doing your research.

Assertiveness

Assertiveness is another foundation attribute of influential people. You will exercise little influence if you allow others to push you aside, or if you simply keep your light under a basket. Sticking up for your own interests in straightforward ways will earn you respect.

Besides cultivating the personal attributes of influential people, there are other behaviors that will increase your influence at the office.

• Enlist the power of reciprocity. Reciprocity refers to the giving of something in return for receiving something. The old phrase “I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine” is based on positive reciprocity. Reciprocity is a powerful force in human society, one that extends to the workplace. A person who receives a favor feels an obligation to repay it in some way—to reciprocate. Thus, every time you do a favor for someone at work—your boss, peers, and subordinates—you add to your “accounts receivable,” or influence.

• Develop and demonstrate expertise. Special knowledge or expertise in an area deemed important by the organization is another source of influence. What expertise is important in your organization? Technology? Customer understanding? An ability to re-engineer work processes to make them faster and cheaper? A relationship with a key supplier? Whatever it is, if you are the master of that critical expertise—the “go to” person—you will have influence. So build expertise in something that matters.

• Create dependencies. As we discussed earlier, the people on whom others depend have influence. For example, if your boss depends on you for generating the production output that makes her look good to senior management (and earns her a bonus), you have some influence over your boss. As you create dependencies within your workplace network, you will gain organizational influence.

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .

Which people in your organization, operating unit, or department seem to have great influence? Forgetting for a moment about the influence that comes with formal authority, explain the sources of their influence. List two influential people below and indicate their source(s) of influence.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Can you think of one person whose influence can be credited to his or her personal attributes? To the power of reciprocity, expertise, or the dependencies of others? Please explain.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

PERSUASION

One of the most powerful ways to influence others is persuasion. Persuasion is the process of communication that enables one person to alter the beliefs, attitudes, or actions of others. Salespeople employ persuasive communication in their work with customers every day. Their goal is to get customers to adopt a positive view of a product or service, to see its benefits to them, and to act by placing an order. If you’re thinking, “That’s fine for salespeople, but I’m not a salesperson, I’m a manager!” think again. You must learn to sell your ideas to your peers, your boss, and your subordinates. You must convince them that your ideas are not only sensible, but in their interests. And you must persuade them to act on those ideas. Successful managers do this all the time. Those managers are less apt to command or compel than to persuade those with whom they work.

If you keep your eyes open for it, you’ll see persuasion applied around you every day. It’s so commonplace that we often don’t think about it. Yet it is essential to getting things done in the workplace.

Exercise 4-2

Exercise 4-2

Your Experience with Persuasion

Look back over the past few weeks and identify three situations in which you or someone you work with used persuasive communication. Indicate the goal of that communication. Finally, note whether the persuader was successful; if not, why not?

THE FOUNDATIONS OF PERSUASION

Like a building, effective persuasion rests on a solid foundation: a combination of trust, understanding of others, a credible case, and persuasive language (Exhibit 4-1).

Trust

We’ve covered this territory earlier in the chapter. Being seen as trustworthy is a key personal attribute of influential people, and it is absolutely critical to anyone who aims to persuade others to his point of view. It’s difficult to persuade people of anything if they do not trust us. Even if we were to tell them that the sky is blue, they might not be persuaded because they don’t trust us.

Would you be persuaded to accept someone’s sales forecast if you thought that person wasn’t knowledgeable about the subject, or was using sloppy forecasting methods, or was trying to pull the wool over your eyes? Would you enter into a negotiated agreement with someone whom you did not trust to carry out her end of the bargain? Absolutely not! Anyone who aims to persuade in the absence of trust faces an uphill climb.

We trust people when we believe that:

• They speak the truth.

• They respect or safeguard our interests.

• They know what they’re talking about.

• They are sincere in what they say to us.

• They have been reliable in the past.

• They will not disclose confidential information.

If asked, would your coworkers say that you have these trust-inspiring qualities? If they wouldn’t, you need to do some rebuilding if you want to be a persuader. The following six “tips” are things you can do today and every day to inspire trust in those around you.

Exercise 4-3

Exercise 4-3

How Trustworthy Are You?

Use a scale of 1 to 5 to answer the following questions and determine whether you can be considered trustworthy; 1 represents the lowest level of trustworthiness and 5 the highest level.

1. Do you always tell the truth in your dealings with others? ___________

2. Do you make an effort to understand and respect the interests of others? ___________

3. Do you speak from expertise in the subjects you deal with? ___________

4. Are you sincere in your dealings? ___________

5. When you agree to do something, do you always follow through? ___________

6. Do you keep confidences? ___________

Understanding

You’ll also be more persuasive in your communications as you come to understand the people you’re trying to influence. It’s intuitively obvious that the more you know about someone, his interests, viewpoints, and needs, the more successful you’ll be in communicating persuasively with that person. You’ll be prepared to deliver your message in a manner that addresses those needs in a positive way.

You can learn a great deal about the needs of others by simply asking questions. For example, a sharp car salesman won’t just point a potential customer to the back lot and hope she finds something she likes. He’ll ask questions first:

“What are you driving now? Do you like it?”

“How large is your family?”

“Are you interested in gasoline efficiency and safety?

“Speed and pick-up?”

“Do you haul a boat?”

You get the idea. Understanding your audience before you try to persuade them is common sense. If, for example, you aim to persuade your boss and coworkers to adopt a new process for handling an essential office routine, try to understand:

• How attached are individual coworkers to the current process?

• How would the change you propose affect them—both negatively and positively?

• Who, if anyone, would resist the change, and why?

• Who, if anyone, would strongly support the change and, perhaps, become your ally?

If you think about the interests of the people you aim to persuade, you’ll be in a better position to bring them around to your point of view.

Understanding the people you aim to persuade includes understanding how decisions are made. This is important because persuasion usually aims to influence a particular decision: a change in the work schedule or process, which new office technology should be purchased, how bonuses will be allocated, and so forth. So, before you try to persuade anyone of anything, determine how the decision that concerns you will be made. Will it be made by your boss or by your boss’s boss? Does the decision require agreement among members of a committee?

Typically, lower-level managers are allowed to decide on the small local issues, while bigger decisions are pushed up the chain of command to more senior managers, the executive team, the CEO, or even to the board of directors. In some departments, project or work teams can make decisions up to a certain level. When decisions affect many people or departments, a committee usually has the final say—and that committee may seek input and advice from specialists. For example, within large corporations, recommendations on salaries and bonuses for senior managers are generally made by board-level compensation committees. Those committees seek input from the finance department, the human resources department, and in many instances, from compensation consultants.

A Credible Case

The third foundation of successful persuasion is a credible case, based on logic and supported with evidence. People have trouble saying no to logical arguments and evidence. Consider the following example.

When Sarah approached her boss with a proposal for a flexible work schedule, she planned her talking points carefully. “Working from home will allow me to give my full attention to my work. As you know, the kind of keyboarding I do requires intense concentration, and there are always interruptions here in the office. Besides, if I don’t have that hour-long commute to the office, I can get started earlier in the day and do the team’s work planning and assignments before anyone else even gets in.”

“But what about distractions at home?” asked Dick. “Won’t you be tempted by things around the house?”

“I have an office over the garage—it’s separate from the house, so I wouldn’t go into the main house except at lunchtime. And my mother-in-law lives in an apartment in my house, so if one of the kids is home sick she can take care of them.”

By building a credible, logical case for her proposal, Sarah had countered each of the objections she knew that her boss would bring up. So, in the end, he agreed to try out her suggestion. “How could I say no,” he told himself. “She had thought through the important issues and developed a plan I couldn’t disagree with.” This example underscores the importance of something discussed earlier—understanding the people you aim to persuade. Sarah understood her boss’s concerns and how he was likely to respond to her plan. She used that understanding to create a logical argument in favor of her revised work situation.

It’s easy for people to be dismissive of persuasive efforts when the would-be persuader hasn’t done his homework—that is, hasn’t developed a solid, fact-based case. This is especially true when a proposal requires people to change what they are doing or take a calculated risk. But as the previous story makes clear, fair-minded people find it difficult to say no to things that are logical and valuable.

Too many people fail to give proper attention to this third building block of persuasion. They have an idea that makes sense to them, but don’t take the time to see it from the perspective of the people whose approval and collaboration they need.

Persuading Your Boss

Imagine that you want to take one week off to attend an industry conference. You believe that doing so will make you more knowledgeable about the direction in which the industry is heading and also strengthen your network of industry contacts. How can you build a credible case to convince your boss? Before you try to persuade her of the merits of your idea alone, do the following: List three concerns or objections that your boss might have to this arrangement; for each, indicate how you would respond to those concerns/objections in persuading your boss.

Persuasive Language

The three building blocks just described are necessary but insufficient for success in most cases of persuasion. They may get you close to the finish line but you’ll need one more thing to carry you over—persuasive language. You need language that addresses the head (logic) in some cases, and the heart (emotions) in others—and in some cases, both.

Head language is usually most appropriate when the decision hinges on quantifiable information, and when the people involved are analytical and data-oriented—accountants, engineers, strategic planners, stock analysts, and so forth. Head language appeals to the logical mind, which demands reliable evidence. A manager negotiating salary with a new hire, for example, will use industry information, local cost-of-living data, and competitiveness analysis to explain his offer. He will support his case with factual information: “Yes, I know that salaries are much higher in New York, where you’re currently working, but here in Indianapolis the cost of living is about 17 percent less, and salaries reflect that.”

In some cases, however, persuasion is more effective when it speaks to the heart. Every great public speaker understands the power of an emotional appeal. Consider Winston Churchill’s famous broadcast to the British people in the early days of World War II, when their army had been defeated in France and the island nation stood alone against the more powerful forces of Nazi Germany. Churchill did not cite dull statistics to his listeners. Instead, he spoke to their hearts, evoking the emotional courage they would need to carry on during the months ahead.

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous states have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail.

We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. . .

In some cases, a successful appeal to the heart will outweigh whatever weaknesses the logical case may have.

Persuasive language also emphasizes benefits. Every salesperson knows the difference between features and benefits. When someone says “This computer has a 2.33 megahertz processor and a VereX bus,” that person is describing features. Features are necessary in that they set the groundwork. You should communicate them, especially if your audience is technically oriented, or if the discussion calls for a full airing of the details. But many people are persuaded by benefits, not features. Here are some examples of persuasive speech that emphasize benefits:

• “Because this is such a fast computer (feature), you won’t be sitting there waiting and waiting (benefit). And we all hate waiting...”

• “If we adopt the new work process I’ve described (feature), we will improve employee productivity by 20 percent. And that will save our department $180,000 every year. That’s money we could share between our owners and employees (benefit).”

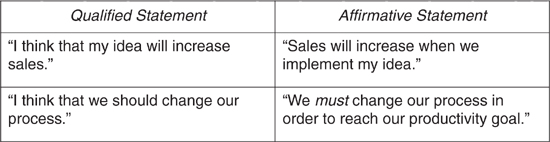

When speaking persuasively, be positive and affirmative in communicating your ideas.

Some people cannot make an unqualified statement. “I think that . . .” is their preferred opener to every statement. If you’re trying to persuade someone to adopt your view, don’t say, “I think that . . .” You might as well say, “I’m not sure, but. . . .” These qualifications tell listeners that you may be wrong, or that you lack confidence in your view, or that you’re offering nothing but a personal opinion.

If you have built a credible case, you can make affirmative statements with confidence, and your confidence will inspire confidence in your listeners.

Also, minimize the use of “if.” “If we manage to change our process, productivity will improve.” This is another qualifier. Instead, be affirmative and say something like this: “When we change the process . . .” or “Once we’ve changed the process, productivity will improve.”

What are your sources of influence? Whatever they are, use your influence as you would your formal authority as a manager—that is, use it sparingly and wisely. Think of your influence as a work in progress: it is always being either enhanced or undermined by your actions, and it is only as strong as your most recent behavior. Using your influence unfairly or for the wrong ends will only destroy it. Once destroyed, it is almost impossible to rebuild.

Managers often find themselves in situations where they must produce results through other people over whom they have no power or authority. Even when they do have authority, their dependence on others limits their ability to exercise it. In these cases, the ability to persuade and to influence can help them get the job done.

Influence is a tool that managers can use to accomplish their goals when they lack organizational authority. Influence refers to a person’s ability to alter or affect the behavior of others without recourse to the power to command. Managers can increase their influence by cultivating the personal attributes of influential people: trustworthiness, reliability, and assertiveness.

Persuasion is a communication process through which we alter or affect the attitudes, beliefs, or actions of others. The four building blocks of persuasion are trust, understanding, a credible case, and persuasive language. To build trust, always behave in a trustworthy way. Increase your understanding of the people you are trying to persuade; you should also become aware of how decisions are made in your organization, and identify the key decision makers for the decision you are trying to influence. Build a credible case by checking your assumptions, being aware of alternatives to your idea, developing a contingency plan, and obtaining endorsements from others. Finally, to be successful in persuasion, use the language of persuasion. Emphasize the benefits of your proposal; speak to both the intellect and the emotions; use positive, definite language—and, when possible, cite endorsements from others.

xhibit 4-1

xhibit 4-1