8

Managing Performance

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• Explain the purpose of performance management.

• Describe the performance appraisal process and its steps.

• Identify four important characteristics of effective feedback.

• Articulate the purpose of coaching and its process steps.

As a manager, your success depends on how effective your subordinates are at their jobs, and how effectively they work toward personal and unit goals. It is your job to define their objectives, assess their progress, and help them reach their goals. Through performance management you can assure the success of your department by improving the performance of individuals.

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

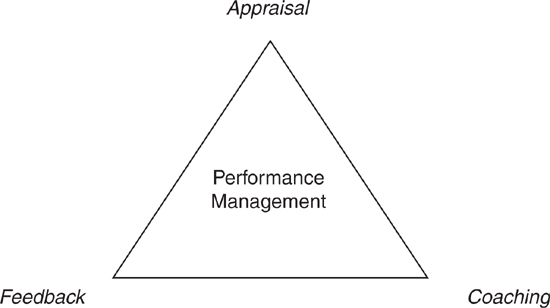

Performance management is a set of activities that managers use to measure and improve the effectiveness of their subordinates. This chapter focuses on three tools in particular: performance appraisal, giving and receiving feedback, and coaching. These work together to help managers and their subordinates identify performance problems and opportunities and to address them effectively (Exhibit 8-1). Other elements of performance management include motivational rewards, employee training, and career development, which are beyond the scope of this chapter.

PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL

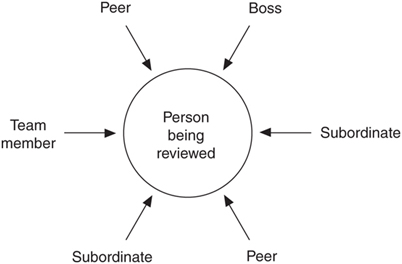

Performance appraisal is a management practice that aims to assess how well an individual measures up to unit standards and/or his or her assigned goals. Its findings are used for pay and promotion purposes, as well as employee development. It will be described here through a series of steps that the new manager can follow, the first being agreement on performance expectations and individual goals. The pros and cons of 360-degree appraisal will be included in the discussion via a sidebar.

Many companies conduct an annual formal performance appraisal, followed by periodic review. Appraisal of individual employees begins with their individual goals. At the beginning of the appraisal period, these objectives are established through discussion between the manager and employee, and then confirmed in writing. It is very important that the employee and his or her manager agree on those goals.

Goals, then, are the yardstick against which performance is measured. The manager notes whether the employee exceeded the goals, met the goals, or if there are gaps between assigned goals and what the employee actually accomplished. If gaps are found, the manager and employee will then try to find the causes. Perhaps the employee has not been diligent; perhaps his or her skills are insufficient to the task. Perhaps something in the workplace environment over which the employee has no control—such as insufficient resources—explains the problem. Whatever the causes of performance gaps, the act of finding them through the appraisal process is the first step toward eliminating them. On the other hand, you may find that the employee has exceeded her goals. It’s important to understand the causes of good news, too. Is the improvement a one-time fluke, or is there something other department members can learn from Susan’s achievement?

“Susan, we asked you to decrease costs in your area by 15 percent this year. Congratulations! You achieved a 23 percent decrease! How did you accomplish that?”

A Six-Step Process

Busy managers seldom look forward to the annual employee appraisal. It’s a chore that eats up time—especially when they have many direct reports—and it puts them in the position of passing judgment on others, which many people find uncomfortable when deficiencies exist. Though positive appraisal reports produce good things for their subordinates (raises, bonuses, promotions, and goodwill), they know that their unfavorable appraisals may result in negative financial and career consequence for people they’ve gotten to know on a personal basis.

One way to take some of the time and discomfort out of performance appraisal is to follow a systematic and objective process. We offer one here. It has six steps:

1. Preparation

2. The appraisal meeting

3. The identification of performance gaps or opportunities

4. Planning to close gaps

5. Recording the appraisal

6. Periodic follow-up

The process works best when both the manager and subordinate are involved in each step.

Preparation

Busy people are tempted to “wing it” as they enter the appraisal process; they schedule a meeting time, look through the employee’s file fifteen minutes ahead of the meeting, and take it from there. This casual approach will not produce good results. The manager’s preparation should begin at the start of the appraisal period with direct and regular observation of the subordinate’s work. Does he appear to be having trouble? Is her work completed on time and up to standards? Is he collaborating with coworkers, and so forth? It’s a good idea to record those observations in the employee’s file as they are made. Since we all tend to remember recent events and impressions more than those experiences in the distant past, the manager who revisits observations recorded over time is less likely to base his overall judgment of employee performance on what he observed in the previous week or month.

The employee being appraised should prepare in a similar fashion, making notes on what he or she has done well or poorly, what resources (such as training) would lead to better future performance, and so forth.

Shortly before the appraisal meeting, the manager should obtain any relevant up-to-date statistics from an accurate and neutral source: sales data from the financial system, error rates from shop floor records, and so forth.

The appraisal meeting should be held in a setting that will make both parties feel comfortable and encourage dialogue. It’s usually best to begin by encouraging the employee to express his or her views. “Please tell me how you feel about your work over the past year. Do you feel you’ve done well relative to the goals we set this time last year?” Then, give your full attention to the response.

In fact, the employee should do most of the talking in this conversation; you should focus on listening and try to talk less than a fourth of the time. You need to hear the employee’s version of reality. Avoid the temptation to jump in if you hear something with which you disagree; instead, make a quick note of it. Demonstrate your attention through verbal cues, such as, “I see” or “How have you developed good rapport with your teammates?” Ask questions to learn more. For example, “One of your goals was to develop productive relationships with our key customers; how do you feel that you’ve done in that area?”

When assessing performance, point to successes and failures—and don’t fixate on the failures if doing so would give an unbalanced view of the employee’s performance during the year. Also, avoid unsupported generalizations, such as “I don’t think you’ve done a very good job in supporting our customers.” If you have a complaint, document it in some way and be sure to explore causes: “Our annual survey of your customer accounts showed a 20 percent reduction in post-sales service satisfaction. What’s going on here?”

Throughout the meeting, keep the focus on goals that you and your subordinate agreed to during previous appraisal session. The tips in Exhibit 8-2 will help you keep the meeting on track.

Identification of performance gaps or opportunities

Performance can exceed expectations, meet expectations, or fail to meet expectations. If you keep the focus on goals, and if those goals are specific and measurable as we discussed in Chapter 6, you and your subordinate can have a productive conversation about performance. You should discuss and praise positive results: “You exceeded your goal of new client acquisition by 30 percent. That’s fantastic. Tell me how you did that?” You must also identify and point out performance gaps and their causes: “But you fell short of your sales quota by 18 percent this year. What accounts for that shortfall?” Listen carefully to what your subordinate says about his or her performance shortfalls, as you may learn something that will help the two of you get things back on track. You may discover, for example, that you are part of the problem: you haven’t given the person sufficient time or resources to complete her tasks; or your directions may have been ambiguous. You may also discover that the person has had insufficient training. Listening can help you identify opportunities to improve the performance of this employee and others in your organization.

Tips for Conducting an Appraisal Session

Be professional, serious, and focused on performance issues.

Listen to the employee.

Acknowledge good performance before you move to areas of weakness.

Don’t generalize. Provide specific examples of performance that concerns you.

Keep your subordinate involved in the discussion.

In the end, summarize your assessment and any improvement plan the two of you have agreed to follow.

Restate the person’s goals going forward. Secure your subordinate’s agreement on those goals.

If performance gaps are apparent, be sure that the subordinate recognizes them. You don’t want that person to leave the meeting thinking that everything is fine and that her performance meets expectations.

Planning to close the gaps

Once you’ve discovered the cause of performance gaps, you and your subordinate will be in a position to eliminate them through coaching, formal training, or other means. The subordinate must be fully involved in any plan to improve performance, otherwise you are unlikely to get the desired results. So give your subordinate the first shot at planning the solution. “Okay, we have both acknowledged the problem. So tell me, what in your view is the best way to fix it?” If his or her solution appears sound, defer to it in your action plan. The subordinate is more likely to take the action plan seriously if he or she thought of it and proposed it.

A good action plan for performance improvement will have specific goals, a timeline (including any intermediate steps), and the employee’s formal agreement. Set that plan in writing, put it in the employee’s file, and give the employee a copy.

Recording the appraisal

An appraisal session should always end with a look forward to the coming year. The appraisal meeting is the time to revisit assigned goals and discuss them with the employee: Are those goals still appropriate? Is it time to set the bar of performance a bit higher? Can the employee “stretch” to a new level of performance? Discuss goals with the other person and, if a change is appropriate, get his or her agreement.

Most companies have a standard performance appraisal process administered by the human resources department. Formal performance appraisals, such as the type we’ve described here, are typically recorded in writing and signed by the manager/supervisor and the employee, with the original going to the employee’s personnel file in HR, and a copy given to the employee. That record becomes the basis for promotions and demotions, changes in compensation, and in the worst cases, discipline or dismissals. Many company human resources departments have a standard form for making and recording performance. If your company does not have one, consider the material in Exhibit 8-3.

Grading Performance

As you record your appraisal of employee performance, focus on quality, quantity, timeliness, and cost-effectiveness.

• Quality is a measure of the accuracy, effectiveness, or usefulness of the employee’s work. If you’ve made goals specific and measurable, you can use error rates, customer satisfaction, and other metrics to assess quality.

• Quantity. How much work did the person produce? Did the quantity equal, exceed, or fall short of goal?

• Timeliness. Were assignments completed on time?

• Cost-effectiveness recognizes the employee’s contributions to cost savings or control—reducing the cost of each unit of output, eliminating waste, and so forth.

Characterize each category of the employee’s performance in terms of a rational scoring system: Excellent, fully successful, adequate, minimally successful, and unsatisfactory. These are roughly equivalent to the A, B, C, D, F letter grades that people already understand.

After the meeting, record the date of your appraisal session, make a note of any disagreements you and the employee have about his or her performance, and describe the new goals the employee will pursue during the coming year, if any. If a performance improvement plan is part of your appraisal, attach a signed copy of the plan.

Periodic follow-up

Action plans intended to improve performance count for nothing unless people execute them effectively and with real dedication. As a manager, you cannot put your subordinate’s performance improvement plan in the file and think that your job is done. You must monitor compliance with the plan, meet periodically with the subordinate to ask how things are going, and check progress against the plan’s goals and timeline. If progress is falling short, your intervention will be required.

A manager should also follow up on the progress from time to time. Don’t wait until the annual performance review to find out that the employee did not understand the objective, or that the objective is not realistic. Use informal meetings to ask, “How are you progressing with the goals we set during our last appraisal session? Are you having any difficulty? Have we given you adequate resources to reach your goal?” Most people are reluctant to tell their boss that they’re falling behind, so probe beneath the surface of their answers for evidence that things are in fact on track, and listen for any muted appeals for help.

Preparing for a Performance Appraisal

Consider one of your subordinates.

1. What are that employee’s goals for this appraisal period?

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

2. Check your files for notes you have made during the course of the year on accomplishments, problems, and the feedback you gave the employee at the time.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

3. How will you measure performance? Do you need to obtain any data?

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

4, Has this employee exceeded your expectations in any areas? Are there areas of needed improvement?

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

5. If there are gaps, have you discussed them in ongoing reviews?

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

FEEDBACK

Feedback is communication that provides information about how well a person is performing against expectations. Feedback helps subordinates and managers better understand mutual expectations, celebrate successes, address workplace problems, and seek improvement. It is a two-way conversation, and is most effective when the parties trust each other and when both are good listeners and explainers.

The term feedback refers to the process by which information about a system’s output returns (is “fed back”) to its source so that future output can be regulated or adjusted. In your car, for instance, there is a feedback link between the radiator and the engine temperature gauge on the dashboard. That gauge asks, “How hot is the engine?” and a sensor in the radiator feeds back—that is, communicates—that information. If the gauge registers abnormally high engine temperature, the operator is alerted and can take corrective action. Exhibit 8-4 is an example of a “feedback loop,” showing a signal or communication going out from A to B, and then being fed back to A.

The annual performance appraisal described in the first section of this chapter is used, in part, to generate feedback between managers and their subordinates. That is a formal approach to feedback.

Giving Effective Performance Feedback

Performance feedback used to be called “constructive criticism,” but that only captures a small part of what feedback means. Constructive criticism is something that can be communicated by feedback—and it’s a large part of what supervisors and managers do—but it represents a one-way street in which the listener learns something (usually negative) and the speaker learns nothing. So, as you develop your feedback skills, remember that you must give equal attention to your capacity to give and receive information.

Effective feedback in a workplace setting has several important characteristics:

• It is descriptive, not judgmental.

• It focuses on modifiable, not unchangeable behavior.

• It deals with specific, not general, observations.

• It is well-timed.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these characteristics.

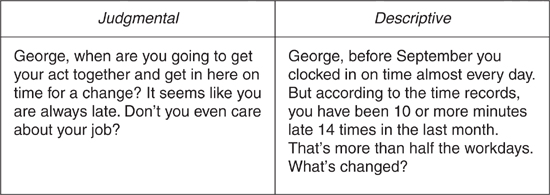

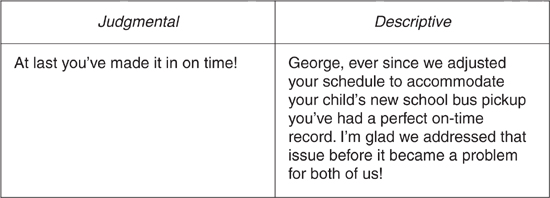

Be descriptive, not judgmental.

Effective feedback does not judge or criticize. It describes. For example, a boss trained in giving feedback won’t say, “You can’t handle the job.” Instead, he will describe what he observes: “I’ve noticed that you’re not entirely familiar with using Excel spreadsheets to report sales results.” Though a sensitive person might hear a note of criticism in that statement, the boss is really describing what he observed.

Feedback should not go beyond what is observed and it should not make a judgment of the person’s motivation. To comment on motivation (“You aren’t interested in what we’re doing here”) would be, at best, guesswork. Judgmental feedback creates defensiveness that prevents the listener from gaining real improvement pointers from the interaction. So when you provide feedback, give concrete examples of the behavior you observe. Focus on the observed problem, not on the person. Compare these two examples.

The descriptive example is clearly less judgmental and more likely to get results. Note that effective feedback usually takes longer to articulate and it begins with the positive and then moves to areas of performance that need improvement.

Even positive feedback should follow the “descriptive” rule. After all, it is the objective results that are important. But do add your congratulations when you convey positive feedback.

Expressing Feedback Descriptively

Think of a performance gap you want to address with one of your subordinates.

1. Express that performance problem here in a judgmental fashion:

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

2. Now express the same issue in a descriptive manner. Remember to start with positive information.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Address modifiable behavior, not unchangeable traits.

Effective feedback focuses on things that can be changed. Most people want to improve their work, and if they are given ideas in areas they can change, they will at least try them. But to be told that you could be better in a particular task if you were taller, for instance, or had a different personality type, is both insulting and useless. Thus, feedback should concentrate on aspects of job performance that are within the power of the listener to change and improve.

Consider the following examples. Which of these two examples focuses on modifiable behavior?

Example 1: Sharon, we need to talk about a couple of aspects of the new operating procedure. Based on the data I am receiving from your workstation, you are entering data meant for an existing customer file and creating a duplicate file. You can avoid this by conducting a search before entering data to see if the customer file exists before assuming you should open a new one.

Example 2: Sharon, how many times do I have to explain this operating procedure to you? Everyone else caught on weeks ago. I’m beginning to wonder if you have the intelligence for this position.

In the second example the manager is criticizing something the employee cannot change, calling her intelligence into question, whereas the first example allows Sharon to alter an aspect of her job performance that is changeable. Focusing on how coworkers can improve areas within their control is a notable feature of effective feedback.

Be specific, not general.

Terms such as always or never are seldom true and are too general for the individual to know where to start in improving job performance. For a supervisor to say “You’re always leaving early” is probably not accurate. Saying “I’ve noticed that you’ve left 15 minutes early every Tuesday and Wednesday for the past month” is both more accurate and specific, and leads to another useful question. “What’s happening on Tuesday and Wednesday that is making you leave—a transportation problem, picking up your kids at childcare?” Feedback that focuses on a specific incident or set of incidents, preferably recent, will be much less personal and more accurate, thus increasing the chances of getting to the root cause of the problem.

Positive feedback should likewise be specific. Saying “That was a terrific presentation” communicates very little useful information to the listener. Saying “Your slides and the pace of your delivery were both very effective” provides much greater information value. The listener doesn’t have to guess at which part of her presentation was so effective. Which of the following feedback examples is more useful?

Which of these examples of negative feedback is not specific?

Example 1: You’re always late with these calculations, Matt. And when you do finally get them in, you are never accurate. I always have to recheck them.

Example 2: The calculations you brought in are two days late, Matt. For the past four months you have been, on average, two or three days late. Your calculations are 82 percent accurate, which is good but not good enough. To make it better, you need to recheck the calculations for our accounts in the South region. They can be tricky. Meanwhile, let’s talk about a time-management plan to help you get these figures in on time.

The first feedback example is very general and offers no concrete evidence for the obvious irritation the speaker feels. In the second example, Matt is more likely to leave the discussion with a clear picture of where his performance needs improvement and how to go about improving it.

Choose your timing carefully.

In most things in life, timing is everything. As a rule of thumb, feedback should be delivered soon after the incident or set of incidents has occurred. This is because the passing of time causes at least two things: memories become inaccurate, and emotions “rewrite” the incident the way a person felt it happened rather than the way it really happened. Emotions can also get in the way if you give feedback too soon after a particular event. More details on how to gauge appropriate timing appear later in this chapter. Now, which of the following two examples exhibits good timing?

In the example of well-timed feedback, the person giving feedback isn’t referring to something that took place a month earlier. As you can see from these examples, timing involves at least two dimensions: giving feedback soon after the incident(s), and making sure the other person has the time to talk.

Exercise 8-3

Exercise 8-3

Your Experience

You have probably received feedback many times, either in the workplace or in school or other environments. Think back to one memorable example—preferably one that occurred in the past week, so that your memory is fresh. In the space provided, briefly describe the nature of that feedback (say, an annual performance review). Then score the feedback giver, on a scale of 1 to 5, on each feedback characteristic (1 = lowest). Follow each score with a brief comment on what was good, bad, or how it could have been done better.

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .

Are you a manager or supervisor? If you are, take a minute to think about opportunities you have in your typical day to provide feedback—positive and negative—to your people. List three of those opportunities you’ve had in the past week. Did you take advantage those opportunities? If you’re not a manager or supervisor, list three recent situations in which you wish that your boss had provided some informal coaching or feedback.

1. __________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

2. __________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

3. __________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

To summarize, here’s a list of Dos and Don’ts for sharing feedback.

Do . . .

• Keep the topic and wording task-oriented, even if the other person tries to personalize it. For example, you might say, “Each of the last two project reports was a week late.” The response might be: “So you’re saying I’m disorganized.” You can then respond, “No, I said that each of the last two projects were a week late. They were well done, but late.”

• Invite the other person’s perceptions. For example, you might ask the person who’s been late in submitting work, “How do you see the situation?” Or, “Have I overloaded you with assignments?” Pause and wait for a response before saying anything more.

• Explain the consequences of the problem you are discussing with the other person. “Being a day or two late with those project reports wouldn’t matter if you and I were the only ones involved. But the marketing group can’t begin its work until they’ve received your report. So, if you’re late, that creates problems for them. Do you see what I mean?” Wait for an acknowledgment from the other person.

• Listen to the answer and clarify any misunderstandings if needed.

• Encourage the person to suggest a solution if you’re discussing a performance gap. If a subordinate offers an acceptable solution to a performance problem, she’ll be more likely to implement that solution than one imposed on her.

• Offer a suggestion if the other person has none of her own. “One way to resolve this would be to put a reminder on your daily ‘to do’ list a week or two in advance—then you can give a few hours each day to the project rather than trying to crank it out right at the deadline.” Then ask for feedback: “How does that sound?” Again, wait for a response.

• Gain commitment to whatever resolution you and the other person agree on. Restate how much you value the person and her work. “So you will block out two or three hours each day to get the next assignment completed by the end of the month? That’s great. You know, Helen, I really appreciate the quality of your work and our working relationship. This is the first time I’ve felt I needed to raise a concern. Thanks for hearing me out.”

Don’t

• Don’t compare the person to others. Avoid saying, “If only you were as organized as Anne—she always gets her assignments completed on time.”

• Don’t put a judgmental “spin” on your feedback. Avoid something like, “This is just another example of how disorganized you are. You have no time-management skills.” Instead, stick to the problem.

• Don’t indicate that there are other problems too; deal with one thing at a time. Talking about other problems will overwhelm the person receiving the feedback and reduce the chance that the current problem will be addressed. Don’t say, “And while we’re on the topic of these reports, they aren’t very well designed. The typeface isn’t attractive at all. I think it needs a design overhaul.” Instead, say, “I’d like to talk about how we can improve the report’s timely delivery.”

Receiving Feedback

Always remember that feedback is a two-way street: giving and receiving information. Your effectiveness as a manager will not be complete unless you master both. You must be ready and willing to receive feedback, even when it takes the form of constructive criticism of your own work or the manner in which you are managing others. This does not mean you should become a doormat or a scapegoat for everything that goes wrong in the office. It means that you should be open and approachable to people who may have something valuable to say. People who are good at receiving feedback:

• Give the speaker plenty of time to talk; they understand that they learn nothing when they are doing all of the talking.

• Give the speaker their full attention; doing so is the only way to capture what they have to say.

• Demonstrate responsiveness to what they hear; if you invite feedback, you have an obligation to respond.

• Ask for specifics. For instance, if a subordinate complains that your instructions are too vague, ask “Can you give me an example of when I’ve done that?”

Exercise 8-4

Exercise 8-4

Your Feedback Experience

Look over your weekly calendar. Are you anticipating a meeting or situation in which you will receive feedback? What feedback would you find most helpful? What criticism do you anticipate? How could you best respond to that criticism? Jot down your answers in the space below.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Closing the Feedback Loop

Remember the definition of feedback? It is the process by which a system’s output (information) returns to its source so that future output can be regulated and improved. The whole purpose of giving and receiving feedback in the workplace is to change behavior so that performance improves. You can help the process along by providing the necessary tools and by checking in periodically to assure that improvement is being made.

Provide the necessary tools.

Be sure that the person receiving feedback has everything needed to change the desired behavior. Perhaps additional training is necessary, or a more flexible work schedule, or the assistance of another employee. So, if you’re giving feedback, make sure that the other person is equipped to act on your input. If you have received feedback, don’t say, “Thanks for the suggestion—I’ll do that” without first checking to see that you have the resources needed to follow through.

Check in periodically.

The next time the task or function under discussion is performed, check to see if any problems have been addressed. If you were the recipient of the feedback this will ensure that you understand in concrete terms the problem and how corrective actions are having an effect. This further shows your willingness to improve your workplace performance.

Checking in also provides an opportunity for both parties to solve any unforeseen glitches in the new method. For instance, let’s say that you were the manager in the previous example. Your subordinate has told you that you don’t always give her enough time to complete assigned projects. A week has gone by and you have two new reports you want her to take on. Once you’ve explained the reports, you might say something like this as a way of “checking in.”

“I know that you’ve had some concerns about the amount of time I’ve given you to complete reports like these. We talked about that last week. So I’m wondering about these. Ideally, I’d like the first drafts of these reports two weeks from today. Does two weeks seem reasonable given your other duties? Tell me what you think.”

COACHING

Coaching is a process through which managers help their subordinates develop skills, prepare for new responsibilities, or eliminate performance problems. Good managers look for opportunities where coaching can improve performance:

• Janis’s boss asked her to plan and organize an interdepartmental meeting. Never having done such a thing, she didn’t know where to begin. Observing her confusion, her boss offered some advice: “Try to break the job down into its major parts: locating the best time and place for the meeting, creating an agenda, inviting the right people, and so forth.” The boss offered to provide feedback on her progress as she planned the meeting.

• Bill had just been promoted to a supervisory position. One of his first problems was dealing with two difficult employees. One of these individuals was chronically late to work; the other spent more time gabbing with others than working. Both were argumentative whenever Bill spoke to them about their problems. “I’m spinning my wheels with these two,” Bill confessed to his manager. “They’re taking up time that I should be spending on other things.” Bill’s boss understood the problem and agreed to show him methods for handling problem employees. “You’re bound to encounter people like these throughout your career,” he told Bill, “so you’d better learn to deal with them now.” They agreed to talk for twenty minutes every Tuesday afternoon for the next month.

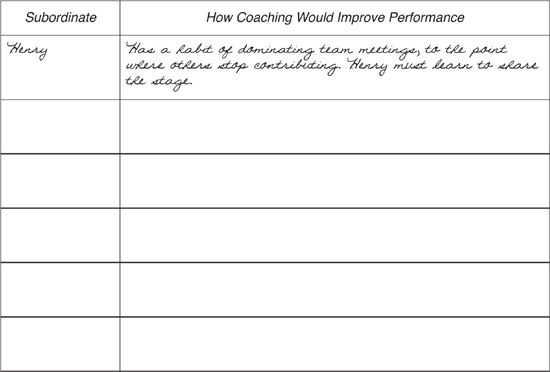

Exercise 8-5

Exercise 8-5

Which of Your People Needs Coaching?

List each of your subordinates (up to five) in the left-hand column. In the right-hand column indicate how these individuals would benefit from coaching by you. (If you’re not yet a manager, play the boss’s role in this exercise and list yourself and your coworkers. What are their coaching needs?) The first row has been completed to serve as an example.

The Coaching Process

Many coaching opportunities can be handled on the spot without planning or preparation. Consider the following example:

Samantha’s subordinate, Charlie, has stopped by to drop off a report he was assigned to write. “This is my first draft,” Charlie said. “You asked to see it before I finished it off and sent to the corporate staff.”

“Right,” Samantha replied as she scanned the draft.

After a moment, she gave her assessment—and some advice. “You’re off to a good start here, Charlie. You’ve covered all the key issues. It’s very thorough. But let me give you a tip: Most of the corporate people will be looking more for your conclusions than the details. They only have time to scan these reports.”

“So what should I do in the final draft?” Charlie asked.

“Give them what they want. State your conclusions up front, in summary form, and move some of the nitty gritty to an appendix. That way, the CEO and his people can get what they need quickly, and the few people who need the details can find them in the appendix. Do you see what I mean?”

“Gotcha.”

In this case Samantha provided on-the-spot, informal coaching aimed at improving Charlie’s performance. No preparation or planning was necessary.

Other coaching situations require planning. These situations may involve the manager’s observation of a serious performance gap, as recorded in the subordinate’s performance appraisal. Or the employee may request coaching to develop new skills to move up to a promotion. In any case, manager and subordinate must consider how they will approach the matter, perhaps even working with the human resources department. Together they can develop a coaching plan that lists the objectives of the coaching relationship.

Once the performance problem or learning opportunity has been identified, formal coaching follows a four-step process that involves both the coach and “coachee”:

1. Discussion between the two parties. The manager and subordinate discuss the situation and how they might best address it.

2. Agreement and commitment. They agree on an action plan with achievable goals; both commit to executing the plan.

3. Active coaching. In this step the manager provides one-on-one guidance or instruction. Alternatively, the manager may delegate the coaching role to another qualified person. For example, if the subordinate needs help in making an effective sales presentation, the manager may ask a top sales person to take the subordinate along on a day of customer calls. In either case, there should be plenty of feedback between coach and coachee during this step.

4. Follow-up. The manager must check back later to assure that the subordinate has had the opportunity to practice new skills and hasn’t gone off the tracks. For instance, if you’ve helped someone develop his meeting planning skills, check back with him periodically. Has he planned any meetings, and were they successful? What can he do better next time? Reinforce what was learned and assure yourself that the person is using his new skills correctly.

Performance management is a set of activities that managers use to measure and improve the effectiveness of their subordinates. These include performance appraisal, feedback, and coaching.

Performance appraisal is used to assess how well individual employees measure up to unit standards and/or their assigned goals. Appraisal findings are used for pay and promotion purposes, as well as employee development. Formal appraisals follow a process that includes preparation, the appraisal meeting, the identification of performance gaps and their causes, planning to close performance gaps, and periodic follow-up. The appraisal process works best when it is objective and when the appraised employee is actively engaged in the process.

Workplace feedback is communication that provides information about how well a person is performing against expectations. Feedback helps subordinates and managers better understand mutual expectations, workplace problems, and solutions. Workplace feedback is most effective when it is descriptive, not judgmental; focused on modifiable behavior; based on specific, not general, observations, and well-timed. If managers give feedback to their subordinates, they must be prepared to receive it as well.

Coaching is a process through which managers help their subordinates develop skills, prepare for new responsibilities, or eliminate performance problems. Good managers look for opportunities where coaching can improve performance. Most of those opportunities can be handled on the spot, without planning or preparation. More formal coaching, like formal appraisal, follows a multistep process that includes discussion, agreement and commitment, active coaching, and follow-up.

1. To be successful, formal coaching requires: |

1. (b) |

(a) a monetary incentive. |

|

(b) commitment by the coach and subordinate to an action plan. |

|

(c) agreement on unit strategy. |

|

(d) assistance from the human resources department. |

|

2. Which of the following is a characteristic of effective feedback? |

2. (a) |

(a) Descriptive, not judgmental |

|

(b) Negative in tone |

|

(c) General in nature |

|

(d) Intuitive |

|

3. Which of the following steps is common to both performance appraisal and coaching? |

3. (c) |

(a) Behavior change through example |

|

(b) 360-degree feedback |

|

(c) Follow-up |

|

(d) Rewards |

|

4. The starting point for formal performance appraisal is: |

4. (a) |

(a) previously stated individual goals. |

|

(b) corporate strategy. |

|

(c) peer review. |

|

(d) future goals. |

|

5. Performance management is: |

5. (c) |

(a) an approach to disciplining subordinates. |

|

(b) a discipline used to determine employee goals. |

|

(c) a set of activities that managers use to measure and improve employee effectiveness. |

|

(d) based on academic theories of human motivation. |

xhibit 8-1

xhibit 8-1