7

Work Processes and Continuous Improvement

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter you should be able to:

• Explain the concept of business process and why managers must understand it.

• Describe how continuous process improvement eliminates steps and/or activities that add cost, time, and errors.

• Explain the difference between process improvement and process innovation.

Some managers believe that the way to improve employee performance is to motivate their subordinates to worker harder. They give pep talks, offer financial incentives and—when all else fails—apply threats. Those efforts may result in modest productivity improvements, but gains are likely to evaporate when the incentives and the pressure let up. The surest way to make substantial and permanent gains in quality, speed, and cost reductions is to work smarter, through work process improvement. That is one of the key discoveries of the quality revolution that began in Japan’s post-World War II era and diffused to North America in the 1980s and elsewhere in the years that followed.

This chapter introduces three related concepts you need to understand if your goal is to get people to work smarter: business processes, continuous process improvement, and process innovation. These are among the most important new ideas to enter the field of management in the past fifty years. Once you understand these concepts, you will see your subordinates’ tasks with new eyes and find ways to work with them to improve output and satisfaction. As you seek ways to improve performance, you’ll learn to ask and answer these two important questions:

1. What work processes are under my management?

2. What can I and my people do to make these processes more effective?

WHAT WE MEAN BY BUSINESS PROCESSES

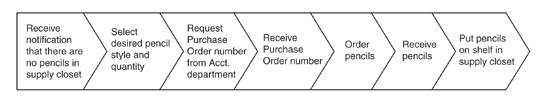

Organizations produce goods and services through what are generally called business processes. A business process is a set of repeatable activities, or steps, that transform inputs into outputs that customers value. Consider the example of the continuous casting process of sheet steel making used by Nucor Corporation. Its “mini-mills” purchase scrap steel, melt it in electric arc furnaces, then pour the molten steel through a caster, producing a continuous, thin ribbon of steel that is eventually cooled, cut, and shipped to customers. Nucor’s process has several inputs (scrap steel, labor, electricity, and machinery) and process steps (purchasing scrap steel, melting, casting, and so on). If we were to “map” this process, it would look something like the linear one shown in Exhibit 7-1.

As you would imagine, the business of making steel is more complex than what is shown in the exhibit. Each of the six steps in reality contains many sub-processes. And the company has a number of support operations (such as accounting, marketing, and human resources) that each have their own processes. However, the steps in the exhibit do, in fact, describe Nucor’s process for making sheet steel.

Business processes are not unique to manufacturing, but are found in service firms and non-profit organizations as well. Consider the lending department of a commercial bank. Like the steel-maker, it creates value by converting inputs to outputs through process steps, as in this simplified example:

• Step 1. Have the customer fill out a loan application.

• Step 2. Check the application. If the applicant appears creditworthy, pass the application on to Step 3; if not, reject the application and communicate the decision to the applicant.

• Step 3. Verify the applicant’s credit history in greater detail. If acceptable, move on to Step 4; if not, reject the application and communicate the decision to the applicant.

• Step 4. Appraise the value of the collateral. If the value exceeds the requested loan amount, continue to Step 5. If not, reject the application and communicate the decision to the applicant.

• Step 5. Commit to the loan and assemble all documents for closing.

Assuming that all went well, this loan approval process would continue on to a successful closing, in which the applicant would sign all necessary papers. Each step of the process, from beginning to end, would involve people, procedures, and their management.

Exercise 7-1

Exercise 7-1

Your Work Processes

CONTINUOUS PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

Understanding your company’s or department’s business processes is the first step toward greater output quality, speed, and lower cost. The next step is to find ways to improve them—not just once, but repeatedly. Continuously. Continuous process improvement (CPI) is a management philosophy that continually reexamines business processes in an effort to find and eliminate steps and/or activities that add time, cost, and errors. Japanese industry is credited with perfecting continuous improvement—or kaizen—as a management approach. For them, it was a way to eliminate waste in materials, time, and error rework, and it became a central feature of the Toyota Production System.

The starting point of continuous improvement is a clear understanding of work processes, which are documented through a technique called process mapping. Process mapping defines in graphic form, usually as a flow chart, the pathway through which inputs are turned into value-added outputs. A process map records the entire sequence of activities, the exact inputs, who does what, who has responsibility, and the measures of successful output. Those measures may include the process’s cycle time—the amount of time required to run a piece of work through the process—process costs per unit, the percentage of output units that meet quality standards, or something else.

Define the Beginning and Ending

The first step in process mapping is to identify where the process begins and ends. The beginning may be triggered by someone’s action. That person might be inside or outside the organization.

• A customer enters an order on the website, triggering the order fulfillment process.

• A customer calls with a problem or complaint, initiating the customer service process.

• One of the outside sales representatives submits her weekly expense account, triggering the employee expense reimbursement process.

The end of the process typically occurs when the process product or outcome is complete, or when work is handed off to another process group. For example, the order fulfillment process is deemed complete when someone in the shipping department has packed the order, affixed an address label, and placed the package on the loading dock. The employee expense filing process ends when the person handling it forwards all the paper work and an official request for payment to the accounts payable department.

A process’s beginning and ending, and all the activities between them, can be mapped in flowchart form. (See Exhibit 7-2). In some cases processes will cross department boundaries.

Exercise 7-2

Exercise 7-2

Creating a Process Flow

1. Look at the process map for ordering pencils in Exhibit 7-2. What is the beginning or triggering event?________________________________________

2. What is the end of the process?__________________________________________________

3. This process intersects with the Accounting Department. The Accounting Department very likely has a standard process of its own for approving Purchase Order requests. Can you imagine what some of the steps might be?___________________________________________________________________

Look for Improvement Opportunities

When processes are mapped carefully, with each step noted in detail, opportunities for improvement may appear. Exhibit 7-3 is a representation of some of the steps in the process we just mapped.

Once a manager and his or her subordinates have the process map in front of them, they can evaluate its component parts with the goal of finding any activities that:

• Add more cost than value.

• Could be done faster or better.

• Could be eliminated entirely with no reduction of output value.

• Could be done in parallel with other activities.

This exercise should be approached with objectivity and as a learning experience by the entire work team. There is no place in this exercise for placing blame. The goal is to find weaknesses in an inanimate thing—the process—not with the people who have been asked to make it work. Look again at Exhibit 7-3. It is probably not really necessary to rethink the style of pencils the department uses each time they are purchased. A time-saving process improvement would be to keep the item number and reorder quantity of frequently ordered items handy—maybe even on the shelf where the pencils are stored.

Involve the Right People

The most productive way to pursue continuous improvement is through the people who manage and work the business processes in question. These people have the best understanding of the process, its strengths, and its weaknesses. Chances are they already have a number of good ideas. It’s not a job for consultants or staff personnel, except in a facilitative role. At Toyota, kaizen groups are formed at the workstation level and are guided by their line supervisors. Further up in the organization, managers examine larger components of the production system. Over the years, this approach has enabled Toyota to improve the quality of its products, reduce cycle time, and cut costs. Others who have adopted this management tool have experienced similar results. Improvements are usually produced in small increments, but those small increments add up over time.

Exercise 7-3

Exercise 7-3

Implementing a Process Improvement

Look for Root Causes of Problems

Opportunities for process improvements are generally available when we recognize a problem and ask “why?”

“Why does it take us so long to process an insurance claim?”

“Why does one out of every 20 products come off our assembly line with one or more defects?”

“Why has the number of worker injuries gone up in the warehouse over the past year?”

“Why are so many of our mail order customers complaining about receiving damaged goods?”

A manager who didn’t understand processes or process improvement would try to answer these questions by blaming people.

“Insurance claims take a long time to process because our employees are working too slowly.”

“Defective products are coming off the line because assembly workers are goofing off—not paying attention to their jobs.”

You get the picture.

Instead of instinctively blaming people for an observed problem, a process-savvy manager will suspect that something is wrong with the process; his or her first act will be to seek out the root cause of the problem. A root cause is the initial cause in a causal chain. Do you remember the old British rhyme:

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

That rhyme describes a causal chain in which a root cause, lack of a horseshoe nail, produced a hugely unfavorable outcome: loss of the kingdom. In a causal chain, the best way to cure the unfavorable outcome is to eliminate the root cause.

Unfavorable outcomes in business processes are often the “effect” of hidden causes. Though it’s tempting to deal with the effect, doing so doesn’t really solve the problem. Thus, if management complains that it’s taking too long to process insurance claims, we might be tempted to hire more people to handle the workload. That solution would address the effect (slow processing), but would do nothing to eliminate the cause—and the cost of adding more personnel. Or, a manager might try to “inspect errors out” of a product, instead of “building quality in.” Again, the symptom would be addressed without curing the disease.

Root causes are not always easy to determine. One tool for revealing them is the fishbone chart. A fishbone chart, so-called because of its appearance, is a diagrammatic way to work backward from an effect to its root cause. In Exhibit 7-4, the “spine” of the fishbone represents the path from input to output. Each of the “bones” is a potential cause of the unwanted effect: equipment, policies, people, employee tools, etc. The job of the work team is to examine all the possibilities. They must also look beyond the obvious. Thus, cause A may have two possible contributing causes B, and C. Are either of these the root cause of the problems? Thus, if slow processing of insurance claims is found to be the fault of a particular employee (A), the root cause might be something further upstream: inadequate training of this employee (B), or a problem with the employee’s personal computer (C). By exploring all possible causes of the unwanted effect, a process improvement team can pinpoint and then eliminate the root cause

Measure the Process

Measurement is an essential part of process improvement. Measurement tells you if you have a problem—and how big that problem is. Depending on the process, you might measure:

• Customer satisfaction.

• Output volume—for example, number of claims processed each week.

• Quality as a function of how many units of output meet a predetermined standard, or how many units must be scrapped or reworked.

• Number of products returned for warranty claims.

• Percent of on-time deliveries.

• Process cycle time.

• Per-unit cost.

Measure before and after you’ve implemented your process improvements. The resulting metrics show the extent to which your actions were effective.

One way to measure the effectiveness of your processes is through benchmarking. Benchmarking is the act of comparing business processes, time cycles, or outputs to some standard, usually other examples in the same industry. You can measure your results against industry information or other similar processes in your company. If your processes take longer, or are less productive than the benchmarks, then they may be good candidates for a process improvement project.

Measure your Processes

Identify two processes that you are involved with, as either an employee or manager. Then describe how those processes are currently measured. If no one is measuring them, what should be measured? Finally, comment on the effectiveness of those measures. Do they really tell you if your processes are efficient and effective?

Understand the Sequence of Activities and their Dependencies

Many workplace activities are locked into linear relationships where one task must be completed before another can begin, as described in Exhibit 7-5. There you see how an individual must gather data, then analyze it, and then report her findings. One activity must await the completion of the one before it. In some cases, you can reduce the time required to complete a work process if one activity can be done in parallel with another, as shown in the exhibit. Here, a mortgage bank can conduct its property appraisal while its credit analysts are evaluating the loan applicant’s credit and ability to repay. Conducting tasks in parallel saves overall time and is possible when one task is not dependent on the completion of another. Discuss sequence relationships with employees. They may come up with more parallel operations.

Think About It

Think About It

Which of your workplace activities must be done in linear fashion?

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Which tasks must be completed before others can begin?

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Which tasks are currently handled in parallel—or could be done in parallel?

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Empower People

Continuous improvement is a bottom-up activity that depends on the enthusiastic participation and collaboration of the people who operate the business process. It cannot be ordered or driven from the top. Enthusiastic participation and collaboration on the part of process operators is a function of good morale and a sense of ownership and control. People must believe that process improvement will make their work life better and their pocketbook fatter.

The best environment for continuous improvement is a workplace characterized by employee empowerment. Employee empowerment refers to a workplace culture that gives subordinates substantial discretion in how they accomplish their objectives. Managers tell them what needs to be done, but leave it up them to find the best way to do it. Empowered employees are also given greater authority over company resources. For example, an employee who deals directly with customers may be authorized—without first checking with her boss—to give discounts, refunds, or other services in order to resolve problems or correct errors on the spot. Research suggests that empowerment contributes to greater initiative, motivation, workplace satisfaction, and commitment among employees. And that satisfaction and commitment is needed to succeed with continual process improvement. Employee empowerment stands in sharp contrast to command-and-control management, a model of management in which information relative to customers and operations flows upward through the chain-of-command to the top, where decisions are made. Directives based on those decisions are then communicated downward through the same chain of command. This approach to management does not inspire the level of employee commitment and collaboration needed for effective, continuous process improvement.

The contemporary office environment generally offers many opportunities for process improvements. For example, every time employee A does one piece of a job and then hands it off to employee B for the job’s completion, inefficiency can result if the job sits on employee B’s desk for some period of time. And when B finally gets around to doing her part of the job, she must first study what A has done. Can you design a process where time is not lost in transit between workers?

Now think about the work done in your office, including your own. Can you identify opportunities for workflow improvements? Explain.

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

PROCESS INNOVATION

Continuous process improvement is pursued through small, incremental changes. Over time, those changes add up, but usually at a diminishing rate, since the easy improvements are found and implemented fairly quickly (see Exhibit 7-6). An alternative to this approach is called process innovation. Process innovation is a wholesale alteration of a process that results in a major, immediate improvement (also seen in Exhibit 7-6).

What does process innovation look like? Consider the example we used to introduce this chapter: Nucor Corporation and its mini-mill process of casting sheet steel. Its process was a major innovation in the centuries old steel industry—an innovation facilitated by Nucor’s adoption of an unproven technology: continuous casting. Prior to Nucor’s breakthrough, sheet steel had been made through a batch process. In that process, molten steel was poured into mattress-sized, white-hot ingots. Each ingot passed through a long series of rollers and reheating furnaces that progressively reduced its thickness. This process required billion of dollars of capital equipment, huge plants, and thousands of workers. It also required billions more in ore mining, shipping, and smelting operations on the front end of the process.

Nucor achieved the same result at a fraction of the capital investment and cost by totally altering the process. No mining or shipping of ore. No smelting plants. No blast furnaces or miles of milling machines. Instead, it bought scrap steel on the open market, melted it in an electric arc furnace, and used its innovative casting technology to pour a continuous ribbon of sheet steel. That process innovation made Nucor the most profitable steel maker on the planet. While traditional steel makers were losing money and laying off employees, Nucor was making millions and expanding its operations.

Process innovation—whether at the industry or the company level—is an infrequent occurrence, but it quickly takes performance to a much higher level. As the exhibit indicates, performance can be enhanced through the application of continuous process improvement. Together, process improvement and process innovation take performance to super-high levels. At its first minimill, for example, Nucor reaped the substantial benefits of process innovation. Once that process was up and running, its work crews found small ways to make the process work more effectively.

Seeking Process Innovation

The Nucor case is one of process innovation at the company level. Chances are that you are more interested in process innovation at the departmental or work team level. It makes no difference; the principle is the same at every level. Remember our process for ordering pencils? We improved the process by posting the item number and order quantity on the shelf where the pencils are stored. What if the manager and team discussed possible process innovations? Perhaps they would create an inventory management system for supplies, conduct a biweekly stock check, and order every item that was below a predetermined quantity. That way, no one would have to notice that there were no pencils and inform the administrator, and the department would never run out of pencils again.

The question is, how can you and your team create a process innovation capable of improving performance by a huge amount? Perhaps the best way to do this is to:

• Enlist your team in a brainstorming effort; many brains are better than one.

• Suspend all assumptions about what you can or cannot do. You don’t want assumptions to limit your imagining of a better way.

• Describe the output goal you seek. Make it a stretch goal—plan to process a commercial loan application in one day or less instead of three, and reduce customer service wait times by 75 percent. Think big!

Now, tell yourself and your team to imagine that the current process does not exist—that you are starting with a clean slate. Ask everyone to think of how they would design a work process to meet their stretch goal.

If this advice seems far-fetched, consider these examples of process innovation at work:

• To please customers and cut costs, a major life insurance company set a goal of reducing the time needed to approve or deny an insurance application from three weeks to two days. Within one year the company had created a totally new, computer-aided approach to processing applications that met the two-day goal for 90 percent of applications.

• To reduce time and costs in creating the company website, a marketing department invested in a new content management system that automated moving text and images created for printed pamphlets into the website design templates.

• An accounting department created a “fast track” process for paying invoices under a certain dollar amount for individual contractors.

Examples like these can be found in both manufacturing and service industries. Where could you innovate in your department? One final reminder: Many process improvements and all process innovations are changes. As we discussed in Chapter 5, change efforts require careful management.

Working smarter through work process improvement is the surest way to make substantial and permanent gains in quality, speed, and cost reduction. The concepts of business process, continuous process improvement, and process innovation are among the most important recent ideas in the field of management. Managers who understand these concepts will have a clearer understanding of the work their subordinates do; they will also find ways to improve output and satisfaction.

The key steps to process improvement are: (1) define the process’s beginning and end; (2) look for improvement opportunities; (3) involve the right people; (4) look for root causes of problems; (5) measure the process; (6) understand the sequence of activities and their dependencies; and (7) empower people. Continuous process improvement means continually reexamining business processes in an effort to find and eliminate steps or activities that add time, cost, and errors. Process mapping, the starting point for continuous process improvement, records the entire sequence of activities and the measures of successful output. These measures include cycle time and process costs per unit.

Process innovation is a wholesale alteration of a process that results in a major, immediate improvement. It is an infrequent occurrence that quickly takes performance to a much higher level. Some techniques for stimulating process innovation include brainstorming, suspending assumptions about what you can or can’t do, and articulating stretch goals for your team. Opportunities for process innovation may exist where people do repetitive work, where work is handled in batches, where operations are separated by physical distance, and where work could be outsourced to a third party.

xhibit 7-1

xhibit 7-1