10

Handling Difficult People and Situations

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter you should be able to:

• Describe the difference between useful and unproductive conflict in your workplace.

• Describe a two-step process for dealing with difficult employees.

• Describe the challenges and solutions for dealing with high-value customers and difficult bosses.

If you’ve ever worked for yourself and had no employees to worry about, you have probably been as close to a conflict-free working environment as you will ever experience. No egos bumping up against one another. No workers complaining about their pay or peers. Sure, there is an occasional irascible client to deal with, but overall the level of conflict experienced by the independent consultant, tradesperson, freelance writer, and so on is pretty low and easily managed.

Unfortunately, individuals working alone face certain limitations. Big jobs—designing an office building, providing broad-based medical services, manufacturing, and similar activities—require many hands and minds working together. And that’s where the trouble begins. When you bring a dozen people together to do a job, you may get a dozen opinions on how the job should be handled. Among those same twelve people, there’s also bound to be some personal friction that reduces collaboration and performance.

In many respects an organization is like an engine with many moving parts. Moving parts naturally generate efficiency-robbing friction (conflict), and some parts may be defective (a poorly performing employee). One of the manager’s jobs is to minimize the conflict-driven frictions that prevent the organization from fulfilling its productive potential.

Dealing with conflict and difficult employees absorbs a significant portion of the typical manager’s day, and is usually the least favorite part of his or her job. As one business owner told the authors, “My job would be ideal if it weren’t for all the people problems.” This chapter will not immunize you to those annoyances, but it will give you ideas for dealing with them more effectively.

WORKPLACE CONFLICT

Conflict is a state in which the ideas, interests, plans, goals, egos, and agendas of individuals clash. A clash of interests between sovereign states and the federal government contributed to the American Civil War. In Spain, conflict between supporters of conservatism and the supporters of liberal and socialist ideas spilled over into civil war during the 1930s. Organizations do not break down into shooting wars, but conflict over ideas, interests, plans, goals, and individual egos often impede performance. Here are a few examples:

• Winner take all. The Vice President of Sales for a nationwide company plans to retire soon. Two powerful regional sales managers are vying to replace him. One will win and the other will lose in that contest. Both have large egos. Their contentious jockeying for position is undermining collaboration among the sales management team and hurting morale.

• Not good for me. The CEO appointed a cross-functional team to study the pros and cons of purchasing a multimillion dollar “enterprise management” software system. The finance representative on the team is pushing for the system, seeing it as a major time-saver for her department. The information technology person on the team is following his boss’s line in opposing the new system. “We don’t have the resources to implement and debug a system that big,” he complains. “It will be a nightmare for us.” The engineering person on the team is also opposed, believing that the millions spent on a new system will starve his department and others of resources. To the annoyance of everyone else, the engineering representative has been secretly lobbying against the system among senior management.

• Turf warfare. The Vice President of Corporate Marketing and the General Manager of the Consumer Products Division have locked horns in a turf war over which of them will control the Division’s advertising budget. “We’re in a better position to balance ad spending across the entire corporation,” says the marketing VP. The division GM sees a serious loss of control in that idea. “He’s just trying to build a little empire for himself,” he says dismissively of his colleague in marketing.

• It’s personal. Nancy and Brett are both subordinates of Helen, a newly appointed manager. The two were recently romantically linked but now avoid speaking with one another, even though their work cubicles are adjacent to one another. If Nancy has something to share with Brett, she either does so via email or has it delivered by a coworker. No one understands the exact nature of their conflict, but it has made work within the small office difficult for everyone and generated an unhealthy level of gossip.

Do any of these conflicts seem familiar? Chances are that you will have to deal with conflicts like them sometime during your management career.

Exercise 10-1

Exercise 10-1

Conflict Where You Work

Identify one case of conflict you have observed in your workplace, then answer the following questions:

Who is involved in this conflict? ____________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

What is at issue in this conflict (for example, fighting over scarce resources)?

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

What effect is this conflict having on work performance, if any? ____________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Not Always Bad

Some level of conflict is inevitable whenever people are brought together. Conflict, however, is not always a bad thing. Consider its opposite: unanimity, a state in which everyone is in agreement. At first blush, you’d probably say, “What’s wrong with everyone being in agreement?” Well, consider the bad things that happen when leaders surround themselves with like-minded people who will not or cannot say, “I think that’s a bad idea. I know of a better alternative.” People use the term groupthink to describe these situations. People afflicted with groupthink generally have a strong team identity and strive for consensus and conflict-avoidance. As a result, dissenting ideas are suppressed, and dissenters are excluded (“She wasn’t a team player”). People often make big mistakes when everyone thinks the same and when conflicting ideas are suppressed. President Kennedy’s decision to support the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion by anti-Castro Cuban exiles is often described as a classic case of groupthink. Kennedy’s advisors were all in agreement and did not invite dissenting views. Similar forces are common in the workplace, where people often share a common view of the customer and the competitive environment.

Sarah is a new editor of a leading magazine for people who like to cook. At the meeting to discuss possible articles for the September issue, she had some ideas. “How about a feature on tailgating?” “Ha!” snorted Esmé, the editorial director, “Our readers aren’t interested in tailgating! They want elegance!”

“Yes,” piped up Rolando, “It’s simply not what our readers care about.”

“How do we know that?” asked Sarah.

“It’s simple,” responded Esmé. “As the most prestigious cooking magazine in the country, we tell our readers what they need to know. They trust us to identify what is important. We have not selected tailgating. Now let’s see, we need an international feature, a vegetarian feature, and who wants to take on this month’s new and unusual ingredient?”

Heads nodded around the room. Years of pre-eminence in the market niche assured that employees agreed on many things—the infallibility of Esmé being foremost among them. Sarah volunteered for the equipment feature. In October, the magazine’s main rival scored big newsstand sales and free publicity for its cover article: “Knock Their Socks Off! Haute Cuisine Meets the Tailgate.”

A controlled level of conflict is an antidote to groupthink because conflict can raise important issues and people must grapple with them. Consider the example described earlier in which a team of people representing different corporate units were studying the pros and cons of an expensive software system. Conflict within that group served a valuable purpose: alerting management to the potential problems of the system, and the fact that some units might benefit while others would suffer.

Conflict between the VP of Corporate Marketing and the Division General Manager is also useful in the sense that it raises a question of interest to management: Which entity is in the best position to deliver cost-effective advertising for the Consumer Products Division?

Of the four conflict examples presented above, “winner take all” and personal conflicts may be of zero positive value. Conflict between the two competing sales managers does not appear to help their organization. If one is chosen to become the new Sales VP, the other may be bitter or may even leave the company. As for hard feelings between Nancy and Brett, no good can come of their conflict, which is simply making work more difficult for them and their peers.

Valuable Conflict

Return for just a moment to the workplace conflict you identified in Exercise 10-1. Do you see any value to the organization in that conflict—that is, has it forced people to debate important issues? Please explain:

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Dealing with Conflict

Conflict is an inevitable feature of organizational life. Your job as a manager is to:

1. Recognize when conflict adds value and when it does nothing but impede performance.

2. Determine the cause of the conflict.

3. Eliminate unproductive conflict.

4. Keep useful conflict from getting ugly, and eventually resolve it in a manner that maximizes satisfaction for the conflicted parties.

5. Follow up.

Each situation is different, so you must rely on your judgment to determine which conflict adds value and which does not. Unlike useful conflict, which raises important issues, unproductive conflict typically:

• Diverts attention from important tasks.

• Damages morale.

• Polarizes people into hostile and opposing camps.

• Reduces cooperation.

• Leads to inappropriate behavior.

• Does not lead to a beneficial end.

Unproductive conflict, such as the personal rift between Nancy and Brett, should be quickly eliminated. In these cases, communication is often the best remedy. The manager of these individuals might speak with each separately and frankly, pointing out the negative impact of their conflict on the department and their peers. If neither party will change his or her behavior, then the manager must lay down the law. If that fails, someone must be moved out of the department.

A manager may also work to resolve conflict through communication and negotiation. You should, for instance:

• Ask each conflicted party to express their concern or complaint in a calm and rational manner. Others should listen without commenting until each party has had their say.

• Paraphrase the core of each side’s concern or complaint, then ask clarifying questions. “So if I understand you correctly, you think that shifting responsibility for the division’s advertising to corporate marketing will reduce your sales effectiveness. Is that your position?” Once the person confirms that you have it right, dig deeper. “What makes you think that shifting responsibility for advertising would weaken your sales?” The goal here is to get a clear picture of the problem as each side understands it, and to make sure that the conflicted parties understand each other.

• Get people talking about their interests. Interests are often hidden beneath expressed concerns or positions. For example, referring back to the dispute about buying and installing an enterprise management software system, the IT department’s interest may be fulfilling its mission of providing timely and reliable IT services to internal customers. That essential mission may be undermined if its personnel must divert their attention to the huge job of installing and debugging the new system.

Encourage people to set aside debate over their concerns or “positions” and to begin talking instead about their true interests. Each party should understand the interests of the other.

Once everyone’s interests are on the table, you have an opportunity to find a solution that accommodates each person’s interests.

Look for Win-Win Opportunities

There are generally two types of solutions to conflict: win-lose and win-win. A win-lose solution is one in which all value gained by one party is obtained at the expense of someone else, which is why it is often called a “zero sum” game. For example, if two people are competing for a single promotion, the person who gets it wins at the expense of the other, barring some other arrangement. Win-lose situations assume that the value at stake is fixed: if there is only one promotion available, it cannot be divided or shared.

Some disputes are, in fact, zero sum games. But never make that assumption. Instead, look for a win-win solution, one that benefits all parties. You can often find a win-win solution when both parties talk openly about their interests. Dialogue about interests often uncovers opportunities for value creating trades, the basis for conflict resolution in many cases. A value-creating trade is one in which Party A gives something of little value to himself to Party B, for whom that “something” has important value. Party B, in return, gives Party A something that she values very little, but which A values greatly. Consider this example of a value-creating trade:

Alyssia and Jack had been feuding for weeks over 600 square feet of office space that would soon be vacated. Each wanted that space for his or her own department. Eventually, they brought their dispute to their mutual boss, Ralph, who would eventually decide how the space would be used. Each made a case for why they had to have the space, and why they were more deserving of it than the other. Ralph listened until each had their say.

It appeared to be one of those situations where the value at stake was fixed (600 square feet for floor space). “Well,” said Ralph, “what if we divided the space into two equal parts? Would that work for you?”

“Not at all,” Alyssia insisted. “I need 550 square feet to handle the orders for the year-end holiday and the Easter and Mother’s Day crunch. Nothing less will do.”

Jack was almost as uncompromising. “We must have at least 400 feet to assemble and pack the semi-annual sales kits.”

Faced with the dilemma, Ralph tried to think of ways to expand the value at stake and satisfy each party. “You both have a valid point,” he remarked, “but is there any way that each of you could have the entire space at a particular time?”

“You mean swap times?” asked Jack.

“Right,” said Ralph. “Since your tasks are somewhat countercyclical, you would take over the space during those months when you need extra space, and Alyssia would do the same in the months leading up to major holidays.”

“I’m not sure that would work out,” Alyssia said reservedly. “We’d have to check our annual departmental work schedules.”

“Yes, do that,” Ralph suggested. “Sit down together with a calendar and see how you could accommodate each other in using this new space. Then let me know what you’ve found out.”

By ceding the space in the spring, when he did not need it, Jack offered Alyssia something she valued at no cost to himself. Alyssia did the same when she let Jack used the space during her off season. This example is contrived, but it makes the point: When people understand their interests and those of others, it’s sometimes possible to create conflict-resolving trades that satisfy everyone.

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .

Think for a moment about one or more situations in which a value-creating trade led, or could have led, to an agreeable conflict resolution.

Briefly describe the conflict:

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

What were the real interests of the parties?

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

What trades eventually satisfied, or might have satisfied, the conflicted parties?

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Another problem that managers have to address is dealing with difficult people. Although it’s tempting to blame conflict on the personalities of the people involved, this is usually not the reason for office disturbances. Perfectly nice and reasonable people can find themselves in both productive and unproductive conflict with others. And the most “difficult” people that managers deal with may not overtly cause conflict—although their antics can wreak havoc on any organization. Instead, difficult people bring their own challenges for the manager.

DIFFICULT PEOPLE

Every manager eventually runs into difficult people. They are that small minority of customers who are always complaining or insisting that they be given special treatment or favors—more than you’re already giving them. They are the under-performing subordinates who act as if the company owes them a living. Difficult people also include high performers who use their contributions to the company to justify bad behavior. Their behavior can be rude, malicious, or just strange. Your boss may also be a difficult person. As a manager, you must be prepared to deal with a range of difficult people.

No one looks forward to confronting a difficult person. It’s an unpleasant task. Conflict avoidance is much easier and more comfortable. But avoidance is unlikely to cure the problem. In some cases, failing to confront a difficult person may cause serious financial problems for your company. Consider the following example, as described to the authors by the CEO of a small private company:

Harvey was our top salesperson. My predecessor had hired him away from a competitor.

Harvey was a selling dynamo. He brought in orders we never would have gotten without him. But he was also a big headache, insisting that our warehouse fill orders to companies that should have been on credit hold because of receivables 60 days or more overdue.

When our office manager objected, he would threaten to quit, which scared the former CEO, who always backed down. Harvey also lorded over some of our people, telling them that they would be out of work were it not for his sales performance.

When I took over the first thing I noticed was the $260,000 in past due payments owed by one of Harvey’s key customers. After a little digging, I discovered similar, though smaller examples of past-due accounts. The former CEO wouldn’t confront Harvey. I knew that I had to do it, otherwise he might drive us into insolvency.

This CEO eventually confronted his star salesperson, insisting that Harvey collect his customer’s past due receivables and begin following the company’s credit rules. This was a painful conversation for the CEO. Harvey responded by leaving—taking many of his customers with him. “It took us almost two years to recover our receivables and to fill the sales gap that Harvey created when he left,” reflected the CEO. “But it had to be done.”

A Two-Step Process

Yes, confronting difficult people is stressful, but it’s something you must do for yourself and your organization. If you have any reluctance, or experience a sudden attack of “conflict avoidance,” the following process may help you move forward.

Step 1: Prepare

Preparation will put you in a stronger frame of mind. Preparation involves forethought and making notes to yourself:

• Make a written note of the behavior or issue you need to discuss with this person. As with other feedback discussions, it is important to focus on behavior, not character traits. Be very specific: “Late to work ten times in the past four weeks.”

• Write down the negative consequences that result from this behavior or issue: “Other people on the team cannot get started until you’re there.”

• Indicate what must change. You should have in your mind the ideal outcome: “Always on time and ready to work at 9AM.”

• Anticipate what the other person is likely to say and prepare a counterpoint: “Unreliable bus service might be a valid excuse for being late to work once in great while, but not ten times in four weeks. You know when our business day starts. If the buses are chronically late, take an earlier bus. It’s your job find a way to be here on time.”

• Be prepared for diversionary tactics. Difficult people don’t always cooperate by sticking to the issue at hand. “I’ve worked here 14 years and the old boss never had a problem with my schedule. I think I’ll just ask my Uncle Paul, the CFO, what he thinks about it.”

• Have a plan for change. Being the source of the problem, the other person should usually have the first opportunity to create a plan for change. But have a plan of your own in case he or she is uncooperative or needs a suggestion.

Step 2: Set up a meeting

Call or email the person. In a businesslike manner, briefly state your purpose: “I’d like you to meet me in the first-floor conference room tomorrow at three o’clock. It’s about your arrival time at work. I’ll see you then.” If you do this on the phone, do not entertain any discussion beyond your statement. “I don’t wish to discuss this over the phone. We’ll take it up tomorrow at three.”

This type of planning will raise your confidence, stiffen your backbone if that’s needed, and put you in a much better position to deal with the difficult person.

When you finally meet, do so in a business-like setting. Stay focused on the problem. Listen well and patiently, but hold firm to the result you insisted on in your plan.

Another kind of difficult person doesn’t cause performance problems directly, but somehow manages to sow the seeds of unhappiness with her colleagues. This conversation can be more challenging, because you don’t have the performance issue to hang your hat on, and the employee may be careful to be on good behavior in your presence.

“Samantha, several people have told me that you think the company’s sales bonus plan is unfair. Can we talk about the plan now?”

“Who’s been tattling on me this time? Welcome to the police state—a person can’t even state an opinion without having it turn into a big deal!”

“I’m sure you know the plan was carefully designed to increase sales by rewarding successful salespeople, so I’d like to understand your concerns. If we’ve missed something in the plan design, it’s probably more useful to share your concerns with me than with your colleagues—at least I might be able to do something about them.”

As a new manager, don’t be surprised if these difficult conversations unsettle you and drain you of energy. But once you’ve gotten through a few of them successfully, they will become less and less stressful.

DIFFICULT PEOPLE: SPECIAL CASES

When you deal with problem subordinates, you have something they lack: organizational authority. If you stay within the scope of your authority, your boss and company will back you up, and you will be able to enforce the outcome you see as necessary. The same method can be applied when dealing with your peers, even though you lack the leverage of organizational authority. But you’ll need to alter your approach a bit in dealing with two very special classes of people: customers and your boss.

What’s the Customer Worth?

Customers are the source of revenue for the vast majority of enterprises, so you need to treat them with special care, especially if you’re in a business with high customer acquisition costs.

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .

Have you ever noticed how hard magazine publishers work to get you to renew your subscriptions? They send repeated letters (YOUR SUBSCRIPTION IS ABOUT TO EXPIRE—ACT NOW!), drop the subscription price, and sometime offer gifts just to get you to sign up for one or more additional year. They make that effort because the cost of replacing defectors is much, much higher than the cost of getting people to renew. Credit card companies and commercial lenders face the same high customer acquisition costs.

What about your business? Is the cost of capturing a customer high or low? Explain:

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Your answer will have an impact on your dealings with “difficult” customers. Whether they demand extra services, pay their bills late, or complain about the products or services they purchase, some customers cost your company more than others. Which ones are worth it?

Some companies are ferocious in their dedication to winning customers and keeping them happy. As a marketing executive of an entrepreneurial company told one of the authors, “We always say yes to our customers. Then we go back to the office and try to figure out how we can make good on our commitment.” That’s an extreme approach, but one that has enriched that particular company and its shareholders.

Most customers are fair-minded in their relationships with vendors. They recognize that both parties—you and they—must benefit. A few, however, can be difficult, and those few can eat up a lot of your time. It’s likely that the 20/80 rule applies to difficult customers: namely, 20 percent of customers consume 80 percent of your customer-tending time. But some of these difficult customers are worth the trouble. One of the authors recalls a particular customer, Frank, who frequently asked for more than he paid for. He would call the office periodically to ask for some favor that went beyond the terms of the customer-vendor agreement—free overnight shipping when the delay was his fault, a rush delivery of printed materials, or special treatment for one of his friends. The office staff hated this and routinely complained about Frank. “What a pain this guy is,” they would say among themselves. “Frank calls here every week or two with something he wants us to do for him—as if we have nothing else to do.” As the company’s main contact with Frank, the author had a different attitude toward this customer. He respected Frank’s professional accomplishments and he saw the problems Frank caused as minor relative to the value he contributed to the company. Of the company’s several hundred active customers, Frank alone accounted for almost ten percent of all company revenues and almost 15 percent of gross profits. “We should all be very happy with Frank,” he liked to remind the office staff. “I wish we had ten more difficult customers like him!”

Not every difficult customer, however, is as valuable as Frank. Dealing with some difficult customers costs money and saps people’s energy—to the point of making them profitless to serve. So you must decide how far you’ll go in catering to these difficult customers.

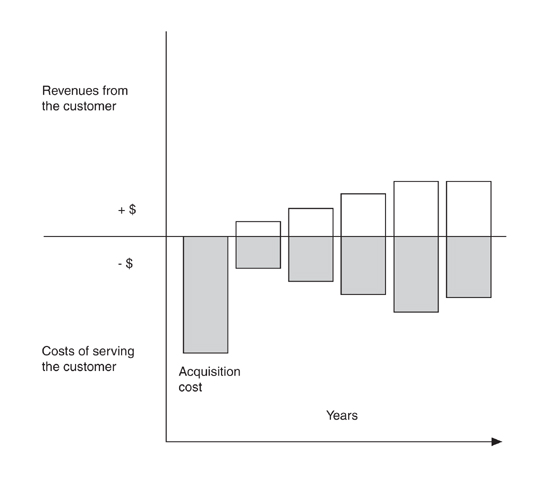

One method for making your decision is customer lifetime economic value analysis. This method estimates the present value of all net cash flows from the customer over a period of years. As shown in Exhibit 10-1, the company experienced an initial cost in acquiring a particular customer. In each subsequent year, serving this customer resulted in a mix of revenues and costs. The net of these cash flows (revenues less costs) were approximately zero during the first year, but increasingly positive (that is, profitable) as time went on—a pattern that every company hopes for in its customer relationships. This customer is a gift that keeps on giving—and worth working hard to keep.

Contrast the positive cash flow of this customer to the situation shown in Exhibit 10-2. Here we have the case of customer who is unprofitable to serve—roughly breakeven on a year-to-year basis. If this unprofitable customer is also a difficult person, you should ask yourself, “Do I want to knock myself out dealing with him?” Unless you anticipate a major change in the value of this customer, you’d be better off parting ways with him. Doing so will reduce stress and give you more time to spend with customers of real value.

Whether you’re dealing with a valuable customer you hope to retain or with a valueless customer you’d like to “fire,” observe these guidelines:

• Be in command of the facts.

• Be totally conversant with your company’s policies regarding discounts, payment terms, and so forth.

• Understand the customer’s interests and your own.

• Listen carefully. The customer may have a valid reason for being difficult.

• Seek a win-win solution.

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .

Can you turn a “difficult” customer into a source of ideas for your company? The extra services and special product tweaks that “problem” customers request can give you a glimpse into your customers’ needs—and maybe valuable new market opportunities. Furthermore, almost everyone likes to be asked for advice and input. Listening to your problem customer may help you turn him into a champion.

Your Boss

Your boss is probably the most important person in your work life. Consequently, if he or she is difficult, you need to find a way to alter the situation for the better.

The problem of difficult bosses is so widespread that a website (badbossology.com) has arisen to provide solace to the multitudes who suffer under them. How do people feel about their bosses? A Badbossology.com survey with 1,118 respondents found that 48 percent would fire their bosses if they could; 29 percent would send their bosses for psychological assessment; and 23 percent would enroll their bosses in a management training course. Another of its surveys found that the majority of employees spend 10 hours or more each month complaining about or listening to others complain about bad bosses, while nearly one-third spend 20 or more hours in boss-bashing. Just how reliable these data are is open to question; nevertheless, they underscore what everyone in the working world knows in his bones: there are a lot of difficult people in management positions. Hopefully, you’re not one of them.

What makes a boss “difficult”? Consider these causes:

• Doesn’t communicate. This is a typical cause of bad-bossdom. Direct reports don’t know their boss’s priorities or his expectations of them. The boss provides no feedback. People are kept in the dark about management’s plans. Lots of hard work is wasted when the boss complains, “That’s not what I wanted. Do it over.”

• Fails to respect subordinates and their contributions. People feel devalued, and that is taking a toll on morale. Failing to get respect, the boss’s direct reports return the favor, creating tension.

• Fails to develop subordinates’ skills and careers. Good managers provide coaching and give their direct reports important, career-enhancing assignments.

They are happy when their best people are promoted into more important positions. The bad boss does not want subordinates to grow professionally—that would only encourage them to leave for a better job.

• Creates a bottleneck. Nothing can be undertaken or decided without this boss’s okay, making her a bottleneck in the flow of work. Since she’s seldom available to make routine decisions, uncompleted work piles up.

• Micromanages. Either through a lack of trust, an obsession with control, or a need to let everyone know that she’s the brightest person in the room, this boss has to be involved in everything and make all the decisions. Competent subordinates feel suffocated.

• Is highly political. Everything this boss does is done to advance his career. He will blame others for his mistakes and take personal credit for their accomplishments. He will also lie and withhold information when doing so furthers his ambitions. He will not support his people if doing so involves a political risk for him.

If you spend enough time in organizations, you’re bound to encounter a boss with one or more of these bad characteristics. Working for any one of them is bound to be difficult—though a useful object lesson in how not to manage people.

Though there are a few personally flawed characters in this list of bad managers, most of them are good people who just haven’t learned how to communicate or deal effectively with the human resources entrusted to them. Perhaps they had no managerial training. Perhaps they learned the ropes of management from a boss who had one or more of those bad habits. Perhaps they are simply buckling under the pressure of their jobs. Whatever the case, if your difficult boss is a fair, well-intentioned person, there’s a good chance that the two of you can develop a productive and mutually beneficial working relationship.

How you build a good working relationship with a difficult boss should be determined by the situation. Much will depend on the nature of the person you’re dealing with and his or her openness to change. The first step, however, is always communication. Even if your boss is closed-mouth and a poor listener, you must find a way to get through. And the most important thing for you to communicate is your interest in helping him or her to be successful. That kind of offer is irresistible to every rational boss—good ones and bad ones alike. Above all:

• Frame your conversations in terms of his or her interests and responsibilities, and how you can help.

• Be very aware of top management’s priorities and concerns, and how your unit, working through your boss, can address them.

Neither of these actions, however, will solve the problem of the difficult boss who is irrational, incompetent, or lacking integrity. In that case, you have two choices: (1) quit or make a lateral move within the organization, or (2) minimize contact with your toxic boss until such time as he or she is forced to walk out. Truly terrible bosses are eventually fired or retired. While you wait for that happy day, build support for yourself within the wider organization:

• Build a strong and supportive network within the company.

• Develop a mentoring relationship with a respected manager or executive who outranks your boss.

• Resist whining about your boss; remain professional at all times.

These actions will provide a measure of employment protection and, very possibly, open the door to a new and better job within the company.

You

Yes, you! The most important factor in keeping employees engaged is a positive relationship with their boss. Look again at the list of behaviors that characterize bad bosses, and honestly assess yourself against them.

Exercise 10-3

Exercise 10-3

Becoming a Good Boss

The “flip sides” of the traits of a bad boss are all good habits to practice. Rate your own behavior from 1 to 10, with 1 being “rarely” and 10 being “always.”

1. I communicate information, expectations, and feedback in a timely and positive fashion.____

2. I respect my subordinates and let them know that I value their contributions.____

3. I work with my subordinates to develop their skills and careers.____

4. When my input is required, I provide it in a timely way.____

5. I delegate appropriately and avoid micromanaging.____

6. I try to be fair and make decisions based on the merits of the case, not on favoritism or office politics._____

Being a good boss is an important part of becoming a successful manager. These actions, as well as the other tips and advice found throughout this book, will serve you throughout your career.

Conflict is a state in which the ideas, interests, plans, goals, egos, and agendas of individuals clash. Workplace conflict can be destructive. Examples of unproductive conflict include: the winner-take-all scenario, where one individual or department wins and another loses, undermining collaboration and hurting morale; the not-good-for-me scenario, in which an individual or a group advances or blocks an agenda based solely on their own interests, without regard for the overall health of the organization; turf warfare, where parties battle for control of resources and influence; and the it’s personal scenario, which develops when personal conflicts spill over into the workplace. Controlled conflict can also be valuable, bringing new ideas to the table, improving discussion, and ensuring that management hears all sides of an issue.

Difficult people can take up a lot of a manager’s time. When dealing with difficult employees, use a two-step process to address the issue. Step 1 is to prepare by making notes on the behavior or issue, noting negative consequences, indicating what must change, anticipating the response, preparing for diversionary tactics, and making a plan for change. Step 2 is to set up a meeting by phone or e-mail to be held in a business-like setting. At this meeting you will listen carefully, while holding firm to the result you outlined in your plan.

When the difficult person is a customer, analyzing his value to your organization will help you determine how best to handle him. One method for assessing a customer’s value is customer lifetime economic value analysis. In dealing with all difficult customers, regardless of value to the organization, you must be professional; in command of the facts; well informed about organizational policies on discounts, payment terms, and so on; understand both the customer’s interests and your own; willing and able to listen carefully; and ready to seek a win-win solution.

Perhaps the most challenging “difficult” relationship is the difficult boss. When this is the case, frame your conversations in terms of his or her interests and responsibilities, and how you can help. Be very aware of top management’s priorities and concerns, and how your unit, working through your boss, can address them. The characteristics of bad bosses—poor communication, lack of respect for others, not developing staff, being a bottleneck, micromanaging, and acting politically—can all be studied as ways to be a better boss.

1. Which is a typical characteristic of a difficult boss? |

1. (b) |

(a) Is too open with subordinates |

|

(b) Doesn’t communicate |

|

(c) Has a process orientation |

|

(d) Delegates challenging tasks |

|

2. In dealing with a difficult customer, you should give some thought to this customer’s: |

2. (d) |

(a) personal feelings. |

|

(b) relationship with your employees. |

|

(c) interest in competing products or services. |

|

(d) lifetime economic value to the company. |

|

3. John has given Bernice a file cabinet he doesn’t need. This helps Bernice immensely. In return, John asks if his people can use Bernice’s photocopier periodically. “Sure,” says, Bernice, “it’s idle half the time.” This is an example of: |

3. (b) |

(a) process sharing. |

|

(b) a value-creating trade. |

|

(c) an even trade. |

|

(d) conflict resolution. |

|

4. A manager should work to eliminate: |

4. (b) |

(a) all conflict. |

|

(b) unproductive conflict. |

|

(c) conflict over the best way to achieve a unit goal. |

|

(d) time spent on discussing differences of opinion. |

|

5. Conflict serves a useful purpose in an organization when it: |

5. (c) |

(a) pits competing employees in winner-take-all situations. |

|

(b) allows managers to exercise their organizational authority. |

|

(c) forces people to raise and debate important issues. |

|

(d) divides employees along loyalty lines. |

xhibit 10-1

xhibit 10-1