Chapter 5

Hospitality

Introduction

In the first section we looked at the procedures required to ensure that the guest gets a room, enjoys possession of it until he is ready to depart, and (to quote the Hotel Proprietors Act 1956 again) ‘pays a reasonable sum for the services and facilities provided’. These are important, but we must now turn our attention to what lies behind them.

In reality, complaints about booking or billing errors only account for a small proportion of guests’ criticisms of hotels. Most hotels have accommodation to spare on all but the very busiest of nights, so even if you've made a mistake over a booking and the guest arrives unexpectedly you can usually room him, if necessary with an apology and perhaps a reduction in price. An error in a bill can quickly be corrected, again with a polite apology. In most cases, prompt and courteous remedial action will disarm criticism, and can even leave a favourable impression.

So what do guests complain about? Well, mainly about a lack of friendliness (and sometimes downright incivility) on the part of the staff. One British survey found that the larger hotels, particularly the chains, were ‘rather cold’ in their attitudes towards their customers, and one of the authors of this book recalls overhearing a guest who was staying at a small private hotel explaining why to his dinner companion. ‘I'm fed up with paying £50 a night in a ... group hotel,’ he said. ‘Only to be made to feel that I'm interrupting the staffs tea break any time I want something’.

‘Hospitality’ and ‘service’ are vitally important concepts. They are also elusive ones which are very difficult to turn into a straightforward checklist of do's and don'ts for new staff. However, they must be considered. It may be helpful if we try to summarize the argument in this chapter:

1 ‘Hospitality’ means the whole process of anticipating and satisfying a guest's needs. This goes right back to the design stage and covers facilities and staffing levels in relation to what the would-be guest is willing to pay. We should therefore start by establishing what these needs are. We will find that although they include tangible (i.e. material) requirements such as a comfortable bed, they also include important psychological satisfactions as well. These depend very much on his current state of mind and his prior expectations.

2 ‘Service’ is closely linked with hospitality, but we have chosen to define it more narrowly in terms of what staff can do to satisfy the guest's needs. We will find that it is not just what is done but how it is done that is important. This links up with our recognition that hospitality involves catering for guests’ psychological needs.

The argument as a whole will lead us to emphasize the importance of the behavioural aspects of face-to-face communications. It therefore leads us to consider ‘social skills’, which we will go on to cover in the following chapter.

Guest needs

The hotel ‘package’

‘Hospitality’ involves anticipating and satisfying a guest's needs. The hotel ‘package’ is a complex one, and the guest's perception of quality depends on the extent to which these are satisfied. However, we must take price into consideration as well: no sensible guest expects to find gold-plated taps in a two-star hotel. In other words, you can have a high quality inexpensive hotel, just as you can have a poor quality five-star one.

Quality is thus a function of the extent to which the hotel satisfies the full range of guest needs, taking price into consideration. It is necessarily a subjective assessment on the part of any individual guest, but if we could somehow combine the various elements we should be able to arrive at an aggregate quality rating in respect of any hotel. We suggest that a possible mechanism for determining this might be as follows:

![]()

Where: Q = Quality

L = Location (e.g. city centre or suburb)

F = Range of facilities (e.g. bath, TV, pool, etc.)

C = Standard of comfort (e.g. warmth, quietness, cleanliness, softness of beds, etc.)

A = Ambience (e.g. attractiveness of decor, etc.)

R = Range of services available (e.g. parking, porterage, concierge, room service, etc.)

S = Speed or promptness of staff service

H = Hospitality (e.g. warmth of the staff s welcome)

P = Price (e.g. is this perceived to be high, average or low in terms of the services and facilities provided?)

All the elements of the ‘package’ have accounting implications (location, facilities, comfort and ambience are initially capital items, but they also involve running costs such as rent, fuel and maintenance; service range and speed are functions of the number of staff employed; while hospitality reflects expenditure on staff training).

The idea is to give a score for each of the package elements. This might be as simple as 3 to 1, with ‘3’ meaning ‘above expectations’ and ‘1’ the opposite. ‘Price’ would be scored on a broadly similar basis, with ‘3’ meaning ‘higher than expected’ and ‘1’ that it is perceived to be low.

Imagine you are a guest and work it out for yourself. If your scores were (say) L = 2; F = 2; C = 2;A = 3;R = 3;S = 2 and H = 3, the average would be about 2.4. Now, if you thought the price high (i.e. 3), the ‘Q’ rating would be 0.8. If you thought it about right (i.e. 2), the ‘Q’ rating would be 1.2, and if you thought it low (i.e. 1), the rating would be 2.4. In other words, the highest rating comes where a high package average is provided at a low price. In simple English, this means that the customers see the hotel as offering value for money.

This ‘quality rating’ of ours is only intended as a conceptual structure (i.e. a way of thinking) about quality in relation to the hotel ‘package’. However, it might be turned into an actual mechanism by asking guests via a questionnaire to score their perceptions using the kind of simple rating system we have suggested: these could be aggregated and a ‘Q’ rating derived.

There is one important point to note, though. If the score in any single element were to drop below a minimum level (reflected by a ‘0’ perhaps), then the rating as a whole would be affected in the same way. The point is that while guests can overlook minor shortcomings, really unpleasant experiences are likely to put them off the hotel for good. Imagine one entering a well-designed, attractive lobby, being greeted pleasantly, shown to a comfortable room and then finding the bath and toilet infested by (Agh!) cockroaches... That ‘0’ would wipe out all the other 3s, wouldn't it?

Tangible and intangible needs

Analysing the hotel ‘package’ shows that the needs it caters for are a mixture of tangible (i.e. physical) and intangible (i.e. psychological) ones. The first involve anything aimed at saving the guest effort or stress. One way of looking at them is to think through what he will require from start to finish of his stay. He will probably have travelled some distance before arriving, and may well be on business. On arrival, he will require:

![]() Easy access to reception and somewhere to leave his car, if he has one.

Easy access to reception and somewhere to leave his car, if he has one.

![]() Easy access for himself and his luggage to his room.

Easy access for himself and his luggage to his room.

![]() A lock and a room key so that he can be sure of privacy.

A lock and a room key so that he can be sure of privacy.

![]() Toilet facilities so that he can ‘freshen up’.

Toilet facilities so that he can ‘freshen up’.

![]() Somewhere to keep his clothing fit to wear, and, for longer stays, laundry facilities.

Somewhere to keep his clothing fit to wear, and, for longer stays, laundry facilities.

![]() Something to eat and drink.

Something to eat and drink.

![]() A chair so that he can relax in comfort.

A chair so that he can relax in comfort.

![]() Alternatively, somewhere to exercise, such as a sauna, gymnasium or swimming pool.

Alternatively, somewhere to exercise, such as a sauna, gymnasium or swimming pool.

![]() Again alternatively, facilities so that he can work in his room, or possibly hold a meeting.

Again alternatively, facilities so that he can work in his room, or possibly hold a meeting.

![]() Facilities so that he can receive and transmit messages.

Facilities so that he can receive and transmit messages.

![]() Some form of individual or group entertainment, such as a TV in his room, or perhaps a disco.

Some form of individual or group entertainment, such as a TV in his room, or perhaps a disco.

![]() A bed so that he can sleep in comfort.

A bed so that he can sleep in comfort.

![]() Some provision for a wake-up call in the morning, an early morning tea or coffee, breakfast and possibly a paper as well.

Some provision for a wake-up call in the morning, an early morning tea or coffee, breakfast and possibly a paper as well.

In cold climates the facilities will have to be warmed; in hot climates they need to be cooled down, or at least ventilated. In noisy environments (such as city centres or the vicinity of airports) they need to be silenced. In all cases they must be clean.

Intangible needs

The approach discussed above tends to lead to a ‘facilities orientated’ approach, whereby hotels are assessed largely on the basis of their physical features (such as the provision of toilet facilities en suite) and the availability of staff to cater for the guest's needs in terms of saving them effort or inconvenience (like portering and room service).

These are legitimate considerations, but they are not'the only ones. What are equally important are the measures taken to make the guest feel welcome and psychologically relaxed. These can be divided into:

1 The ambience (i.e. style and decor) of the building. Imagine a spacious bedroom equipped with every possible facility which is nevertheless painted in dull, monotonous colours and whose outlook is restricted to the local gasworks or an interior wall. A guest could be physically very comfortable in such a room, but that might not prevent him from feeling depressed, even suicidal. Surveys show that guests place a high value on accommodation which is ‘comfortable, pleasant and relaxing’. While comfort has a ‘sensory’ dimension, the other two requirements clearly fall within the psychological sphere.

2 The amount of hospitality or customer care displayed by the staff. It is (sadly) not too hard to envisage a receptionist checking in a guest efficiently but unsmilingly, and it is just as easy to imagine a porter carrying the guest's luggage up to his room in such an ungracious manner as to totally destroy any favourable impression that the physical act itself might have created.

The hierarchy of needs

This analysis confirms that guests have psychological needs which require to be satisfied just as much as their physical ones. But just what are these, and how do they interact?

Maslow's ‘hierarchy of human needs’ is well known. He argues that human beings have a number of different needs, and that the basic ones must be satisfied before the higher level ones. This may well oversimplify the psychological reality, but it provides us with a commonsense conceptual framework which we can all recognize every time we feel the urge to go out for a (basic need) drink in preference to opening our (higher level need) textbook. It also helps us to understand just how psychologically complex the hotel ‘product’ really is, and why the same guest can appear to have different needs at different times. Let us try to follow it through.

1 ‘Survival’. By this Maslow means the need to obtain the basic physiological essentials required to sustain life. Travellers require (in the words of the Hotel Proprietors Act 1956) ‘food, drink, and if so required sleeping accommodation’, and it is one of the hotel's fundamental functions to provide these. At its most basic, this set of needs is met by the more primitive form of hostel. Someone caught in wild, inhospitable terrain at nightfall would be very relieved indeed to find a rudimentary mountain refuge, especially if it contained a stove, a little firewood and a tin or two of food, and we doubt whether such a traveller would worry overmuch about the lack of clean towels or obsequious service. Standards change over time. A century ago it was possible to find examples of very cheap lodging houses offering nothing but the opportunity to sleep propped up against a rope stretched across a room, and even in the 1930s it was common to put same-sex single guests together in the same room (and frequently the same bed). En-suite toilet facilities were restricted to the more expensive rooms, and married couples (and sometimes their children as well) were expected to occupy double beds.

Standards are also relative. A country hotel miles from anywhere else needs to be able to provide some sort of meal for late arrivals, whereas a hotel located in a city centre and surrounded by catering establishments of all types only has to offer some kind of breakfast facilities and need not have a restaurant at all.

2 ‘Security’. The hotel's job is not just to satisfy the guest's basic survival needs. It must also attempt to provide ‘a substitute home’. This is difficult, because the concept of ‘home’ involves all kinds of subtle elements which the hotel cannot hope to supply. After all, ‘home’ is our very own personal territory: we generally have our favourite chair and our own shelf of books or records. Most hotels can't offer anything like this. The dining area is public territory, where most of us feel we have to watch our manners and our general behaviour, the bedroom lacks the cosy familiarity that only comes with long use, and we can't even enjoy undisturbed possession of it because the housekeeping staff need daily access to clean and tidy it.

‘Home’ also usually means family, and here again the hotel situation suffers by comparison. Most business travellers will have left their own families behind at their real homes, and while this may seem fun for a night or two, it rapidly loses its attraction. Even families staying at hotels are placed in an unusual and sometimes stressful situation in as much as they are thrown together to a much greater extent than they would be at home, without the support or refuge of their studies, workshops or gardens.

It is difficult to feel secure in a strange environment, especially when one is also surrounded by strangers. In theory, hotel employees are there to serve the guest, but this doesn't necessarily help: such staff are not employed by the guest but by the hotel, and many people feel diffident about commanding their services under these circumstances.

This feeling of insecurity on the part of the guest needs to be appreciated. It is, obviously, at its most intense when he enters the hotel for the first time. He is likely to have been travelling for some time and will be tired, hungry and in urgent need of a wash and change of clothes. Entering a strange environment under these circumstances is a strain, and such guests are in need of reassurance. They need to be:

– Recognized. If they have to catch your eye, you are already off to a bad start. They also have to be recognized as individuals. ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’ are all very well, but all good hoteliers know that it is the use of the guest's own name which really conveys this impression.

– Persuaded that you are there to help them. ‘Can I help you?’ says it all, quickly and economically.

– Convinced that they are welcome. A smile is one of the quickest and most effective methods of reassuring anyone.

– Assisted into their own personal ‘back area’ as quickly as possible. The term ‘back area’ is a sociological one: it stands for that private space which we all need from time to time: a place where we can relax, let our guards down, conduct running repairs to our appearance and generally prepare for our next foray into the public gaze.

The registration process offers a good illustration of the way that a simple procedure can operate at more than one level at once. There are good practical reasons why the guest should begin his stay by approaching the desk, confirming his reservation, signing the register and obtaining a key. But this process also allows the hotel to offer a whole series of reassurances. Yes, we recognize you as a guest; yes, we confirm that you have a reservation; yes, we are allocating you exclusive use of Room 407; and yes, we appreciate that you would like to get into that room as quickly as possible. As part of this process, the hotel hands over a visible symbol of the guest's occupancy rights in the form of a room key.

Consider the traditional room key for a moment. It is normally a large, solid object, made more so by a massive tag emblazoned with the hotel's name and address in some permanent form. It is bulky and inconvenient. The usual explanation for this is that experience shows that if it isn't large and heavy the guest will carry it around with him during his stay and forget to deposit it with reception when he leaves. But this begs the question of why guests behave in such a way. The fact is that keys are potent symbols (they have a long history as central elements in important ceremonies). You should ask yourself just what the room key might stand for as far as the hotel guest is concerned. Common sense suggests that it is the outward symbol of exclusive occupancy rights to HIS room. If so, you would expect him to be reluctant to surrender it to anyone during his stay, which is precisely what experience suggests is the case.

3 ‘Belongingness’. This recognizes the fact that man is a social animal with a strong need for companionship. Let us see how this applies to our imaginary hotel guest. Once he has checked in, washed, changed and had something to eat and drink, how does he then spend the remainder of the evening? He may, of course, simply read or watch the room's TV for a while, or even go to bed, but a great many guests prefer to come down to the bar or lounge and try to strike up a conversation with any other residents who happen to be there (or failing that, the long-suffering barperson).

This conviviality used to be an attractive feature of the old-fashioned inn. Dickens and other writers have drawn vivid pictures for us of how travellers would congregate in the ‘Common Room’ to exchange news and gossip and to entertain each other with stories and songs. They would often be joined by ‘mine host’, who would not only make sure that they were supplied with drink but also perform any necessary introductions.

This need for companionship is important, but we mustn't forget that it follows the security-based desire for privacy (i.e. the need to retreat into a ‘back area’). This helps us to understand why guests are unlikely to feel very sociable when they first arrive, and only become gregarious after they have had a chance to unwind and get to know the place a bit. It follows, therefore, that satisfying the guests’ need for ‘belongingness’ is more likely to be a feature of longer stay establishments. Experience suggests that this is broadly true.

Successful holiday packages such as holiday camps or cruises provide a whole series of opportunities for the guests to get to know each other, and the organizers employ staff to make sure that the mixing process actually does take place.

A guest can also ‘belong’ to a hotel in the sense of being a well-liked regular, on good terms with the permanent staff. It is relatively easy to create this feeling in a small family hotel, but much more difficult in a large one with high staff turnover, where the guest is likely to meet a different receptionist each time he arrives. One way to overcome this is to maintain guest history records. Another way in which chains create a kind of ‘family’ link is by issuing special privilege cards to their regular customers: as well as entitling such guests to various extra services and discounts, they also perform the valuable role of identifying the guests as regulars entitled to special consideration. This is perhaps not as good as a totally spontaneous welcome based on genuine recognition, but it does go some way towards meeting a need.

4 ‘Esteem’. You might say that esteem (i.e. the need to be liked and respected) follows on logically from belongingness because when we make new acquaintances we want them to think well of us. Unfortunately, guests are (by definition) away from their own home environments, and they sometimes take the opportunity to present their backgrounds in a more favourable light than is really justified (this can result in embarrassment when holiday acquaintances take up their reckless invitations to visit them at home).

Traditionally, many hotels have cultivated an image of social exclusiveness, so that the very act of staying at them enhances a guest's own self-esteem. Although the more extreme forms of snobbery are now much less evident, guests still expect to be treated with respect, if not outright deference. We still call them ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam’, for instance, and we still offer to carry the bags of perfectly fit and healthy visitors.

This exclusiveness is often reflected in high prices. To some extent these are inevitable, because high-quality twenty-four-hour service is necessarily labourintensive. However, the link between costs and prices is only a loose one, and it is well known that a price increase unaccompanied by any change in the tangible features of the ‘package’ can sometimes improve occupancies dramatically. We will consider this in more detail when we look at tariffs.

5 ‘Self-actualization’. This is Maslow's final and highest level need. By it he means the typical human being's desire to improve himself in some way or other, physically, mentally or spiritually. You might ask what this has to do with the receptionist. In fact, it is the basis for a number of extra services that hotels offer, and it is even the reason for a lot of ‘tourist’ bookings.

Take the guest's desire to maintain or improve his physical condition. This is why hotels have long found it profitable to provide swimming pools, and are increasingly finding it necessary to have saunas, gymnasiums and other such facilities. As people become more and more health-conscious, they are being made increasingly aware of the need for exercise, and receptionists need to be able to advise them where and when they might obtain it (by going jogging, for instance).

Mental improvement (in the sense of enlarging one's range of knowledge) is another need which can lead to all manner of unexpected enquiries. Tourists travel in order to ‘see the sights’, and while they may have brought guidebooks with them, a friendly word of advice is almost always welcome. Since receptionists are usually local, they are well placed to provide a ‘bridge’ into the regional culture. They are often called upon to advise guests about when best to visit the local museums, for example, or to bring other attractions to their notice.

The same is true about spiritual improvement. Leaving aside the question of whether tourism is a quasi-spiritual exercise, guests may need some guidance in respect of religious facilities. You may not know the answer to ‘Where is the nearest Greek Orthodox church?’, but it is the kind of thing you might be asked, and you ought to know how to find the answer.

In a much broader sense, self-actualization means enlarging one's whole range of experiences. The longer the guest's stay, the more likely this need is to come to the fore. Satisfying it involves the inclusion of local dishes in the menu, the provision of local folk music and dancing as part of the entertainments offered, and the arrangement of guided tours to local attractions. However, the process of meeting these self-actualizing needs has to be carefully balanced against recognizing the guest's ‘security’ needs. It has been said that tourist hotels located in exotic tropical locations provide a kind of Western sanctuary where the guests can be sure of the water, the food and the plumbing: in other words, a ‘back area’ into which the guests can retreat after their expeditions into the local culture.

Needs in relation to one another

Maslow maintains that these needs form a hierarchy, with each in turn coming to the fore as soon as its predecessor is satisfied. To illustrate this, let us go back to our hypothetical traveller lost in the wilds at nightfall. As we said, he would be pleased to come across even the most villainous of inns. Once lodged there, however, he would start to worry about the safety of his belongings. Reassured on that score, he might well join in the general conversation, and, having done so, would do his best to earn the respect and liking of his companions. At length, having spent an unexpectedly pleasant evening, he might take a last turn outside in order to admire the grandeur of the scenery and reflect a little on the infinite...

Of course, Maslow's needs don't usually pop up to be satisfied one after another in this neat and tidy fashion. They are seldom so clearly identifiable or arranged in such strict sequence, but rather merge into each other so that it is sometimes difficult to say just which one is uppermost at any one time. When a receptionist says, ‘Hello, Mr Jenkinson, nice to see you again. How have you been? We've put you into Room 402 as usual’, she may well be satisfying several of Mr Jenkinson's needs at once: reassuring him that he is expected (security), initiating a friendly conversation (belongingness), and making it clear that he is welcome (esteem). Satisfying three out of five basic human needs in one short exchange isn't bad: no wonder this kind of approach wins repeat business!

Service

The nature of service

As we have seen, hospitality is a big topic which involves the hotel ‘package’ as a whole. It starts with market research and goes on through planning and design to cover issues such as staffing levels and maintenance. Service is that part of the process which involves day-to-day contact between the staff and the customer. This links up with the generally accepted view that services (i.e. the products of ‘service industries’) differ from material goods in that they are:

1 Much less tangible. As we have seen, the service ‘package’ is made up of sensory and psychological experiences rather than objects that the guest can take home and add to his permanent possessions.

2 Much more perishable. Goods can be stockpiled, but services can't. As every commentator on the hotel industry points out, an unsold room night is lost for ever.

3 Simultaneous. The customer has to be there when the service is delivered. This is obviously true in the case of the hotel guest, without whose physical presence the whole concept of a hotel experience becomes meaningless. The situation is quite different for a manufacturing industry, where the factory makes the product long before the customer buys it.

4 Heterogeneous. The product is hard to standardize. Different customers have different needs. It is thus very difficult to establish output standards for a service firm, and even harder to ensure that they are always met.

All this means that the ‘service product’ depends very much on the way the staff behave. This is not true of manufacturing industries. One can admire a finished artefact without worrying about whether there might have been a bitter labour dispute during the manufacturing process, but a comparable event in a hotel would make a guest's stay pretty unpleasant.

Service quality

We need to focus a little more on the nature of this important service element. How can we measure its quality? Well, the customer would expect the staff to be:

1 Reliable. As far as front office is concerned, this means the avoidance of error in every one of the procedures we discussed in Part One, from taking the booking correctly, through allocating a clean and tidy room, to having an accurate bill ready for when the guest wants to check out.

2 Responsive. This means that each service should be available as and when the guest wants it, and not when it happens to suit the staff. It thus covers the important time dimension. In front office terms, it means promptness in answering the telephone and not keeping the guest waiting while you finish your conversation with a colleague or whatever. Management should ensure that the desk is conveniently situated and that customer waiting time is cut to a minimum through sensible staff scheduling.

3 Courteous. This is very much an individual staff responsibility. It means being polite even when the guest is overbearing, inconsiderate or even downright offensive. It can conflict with other requirements such as responsiveness, for it can mean being willing to explain things clearly and patiently even though there is a queue waiting. It can also mean being friendly and reassuring, though it is sometimes difficult to draw the line between being coldly polite on the one hand and too familiar on the other.

4 Customer-orientated. This means putting the customer before the establishment. Any suspicion on the part of the guest that the priorities are the other way round (for example, as a result of his becoming the target for hard selling techniques) is likely to be counter-productive.

5 Confidential. It may be very tempting to gossip about what went on in a VIP's suite the night before, but a hotel which permits this is not providing good service.

6 Caring. This means that staff must make every effort to appreciate the individual guest's needs. As we have seen, these may differ from other guests’ and even change from hour to hour, but recognizing them is a key feature of the service concept. Guests don't like to be treated as if they were all identical, and you need to be able to ring the changes. It is this need to combine individuality of treatment with the maintenance of a consistent overall standard which provides much of the challenge in hospitality work.

This analysis emphasizes the fact that service quality depends very much on how the staff behave in face-to-face encounters.

Service in relation to guest expectations

Most writers agree that the customer's perception of service quality depends on both his prior expectations and his actual experience. This can lead to failure in one of five areas, or ‘gaps’:

![]() Gap 1 Between management perception and customer expectations (i.e. a failure on the part of the former to understand what the latter actually wants).

Gap 1 Between management perception and customer expectations (i.e. a failure on the part of the former to understand what the latter actually wants).

![]() Gap 2 Between management perception and service specification. This could arise if a management aiming to provide five-star service failed to provide enough room service staff.

Gap 2 Between management perception and service specification. This could arise if a management aiming to provide five-star service failed to provide enough room service staff.

![]() Gap 3 Between service specification and service delivery. This could happen if there were enough staff but they failed to respond promptly.

Gap 3 Between service specification and service delivery. This could happen if there were enough staff but they failed to respond promptly.

![]() Gap 4 Between service delivery and advertised quality (‘Yes, I know the brochure says we have a swimming pool, but it's not in use at the moment, sorry.’)

Gap 4 Between service delivery and advertised quality (‘Yes, I know the brochure says we have a swimming pool, but it's not in use at the moment, sorry.’)

![]() Gap 5 Between guest expectations and actual service delivery. This is simple enough in principle, but remember that such expectations will vary according to:

Gap 5 Between guest expectations and actual service delivery. This is simple enough in principle, but remember that such expectations will vary according to:

– The class of establishment. A visitor checking into a remote fishing inn for a leisurely weekend will not anticipate the same kind of service as in a city centre business hotel. He will certainly require competence and courtesy, but he would expect these to be of a different nature. He wouldn't insist that the desk be answered with quite the same promptness, and he would probably look for a slower, more familiar and easy-going kind of courtesy in keeping with the nature of his weekend.

– The personality, mood and circumstances of the individual customer. Some people need a high level of attention, while others don't. Some may want to be flattered and fawned over, while others may not want attention at all, preferring to slip in quietly with the minimum of fuss and bother. Basic personalities may also be affected by specific circumstances. A customer who has just had a bad day will react differently in a service situation from one who has just received good news. The first may well lose his temper over a minute's delay, the second is likely to smile tolerantly.

Roles

One of the things which determines a guest's level of satisfaction is his idea of how a receptionist ought to behave. This brings up the question of ‘roles’.

A role can be defined as the pattern of behaviour expected of a person in a particular position. We expect ticket collectors to collect tickets, just as we expect grandparents to be indulgent. In so doing, they are consciously or unconsciously imitating behaviour patterns which have been laid down by others (whom we call ‘role models’).

Roles do not exist in isolation. Although they may have ‘solo’ elements performed in isolation (like a receptionist checking an arrivals list before any guests appear), they only acquire real meaning in relation to other people. Indeed, slipping through the door leading to the staff quarters offers you the opportunity to step ‘out of role’ for a minute or two. This is often necessary, especially if you have been dealing with a particularly difficult customer.

Because roles involve an ‘audience’ as well as a ‘player’, it is important that both parties should be in broad agreement as to what the role involves. This is called ‘role consensus’. You can't step too far out of character without causing severe problems. A receptionist who is either too distant or too familiar is doing just that, and the guest is liable to be taken aback.

Although we are chiefly concerned with the receptionist's role, you should not forget that customers are also playing one of their own, that of the ‘hotel guest’. Few people spend a lot of time staying in hotels, so this particular role is not as familiar to them as some others. Their relationship with the hotel staff is one of particular difficulty, since very few individuals these days have any experience of dealing with household servants, and find it correspondingly awkward to strike the right note with staff who are there to provide comparable services. They may thus be slightly ill at ease, and it is part of the receptionist's job to ‘lead’ them if necessary.

Roles which involve a lot of customer contact are called ‘boundary roles’, and it is generally agreed that they involve unusual stresses. The problem comes not so much from the need to satisfy conflicting demands (we all face this in one form or another as members of different family, social and working groups) but in having to deal with a number of simultaneous demands while being in a particularly exposed position. Just think of a sole receptionist attempting to cope with a group of boisterous sportsmen trying to check in, a shy foreigner unfamiliar with the requirements of the registration form, and a rather domineering lady who has come down to complain about the room she has been allocated!

The receptionist's role is determined first of all by the management, which lays down the basic ‘script’. It is also influenced by the customers, who provide a kind of interactive audience, and who will soon tell you if they don't like the way you are playing it. It is quite possible that management's and customers’ views might diverge: many managers grew up in the industry and still model their behaviour on the patterns they learned in their youth, possibly with an entirely different set of customers. Roles are also influenced by colleagues, because they are generally learned on the job, usually by imitating an older and more experienced receptionist. Normally this ‘role model’ will have been reasonably successful, but there is always the possibility that the learner will pick up bad habits because older staff sometimes become embittered and even downright hostile.

Most roles can be split down into a number of sub-roles. At varying times during the meal experience, a waiter may be expected to play ‘host’, ‘expert’ or ‘friend’, and the same is true of a receptionist. What is particularly relevant from our standpoint is that receptionists should be seen as helpful.

This discussion does no more than scratch the surface of role theory as it applies to the receptionist's job, but it does offer a ‘dramaturgical’ view of what it involves. This in turn implies that you can best prepare for it by ‘learning your lines’. These don't form a rigid, unchanging script because customers vary in their expectations, but there is enough commonality in them for rehearsal to be useful.

Communication

We have referred to communication a number of times, and we ought to make it clear what we mean by the term. In its broadest sense, it is the exchange of information, news, views and attitudes. The last item is one of the most important, and provides the main link with the theme of this chapter.

Actually, most of our first four chapters have been about communication, because what we have been describing are a series of procedural steps whereby information about a booking is transmitted, stored and acted upon. To begin with, the guest has to communicate his wish to stay at the hotel to front office, and front office has to communicate the availability or otherwise of rooms to the guest. Then front office has to advise the hotel's other departments of the guest's expected arrival so that they can prepare for him, and this, too, involves communication. When the guest arrives, he has to give (i.e. communicate) certain essential items of information to the receptionist as part of the registration process, and these may have to be shown (i.e. communicated) to the police. During the guest's stay he will incur various charges, and these must be communicated to front office so that they can be put on his bill. In due course this will be presented (i.e. communicated) to the guest, who may in turn ask for it to be sent (i.e. communicated) to his employers. Finally, front office must report (i.e. communicate) the results of the day's business to management.

Nor does communication end there. As we shall see later on, many of front office's activities involve communication with other hotels (for example, over guests who have to be found alternative accommodation elsewhere), or with various agencies, from tour operators through to tourist information centres, either because they have contacted it or because it contacts them directly in what is known as a ‘direct selling’ approach.

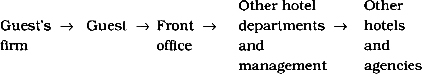

The process as a whole might be shown diagrammatically as shown below:

All this means that communication is at the very heart of front office's operations. If you think about it, almost all the pieces of equipment you are likely to use in your work are in fact devices for storing, processing or communicating information. You will answer the telephone, make notes, enter data into a computer, process vouchers, make out bills and send or file letters. You will either reply to guest's questions directly or look up the answers in appropriate reference books. Just about the only items you will handle that cannot be classed as data storage records of one kind or another will be room keys and guests’ valuables, and even here you will have to issue and check receipts.

There are said to be well over a hundred methods of communication within organizations. As far as hotels are concerned, they include the telephone, letters, fax, computerized displays and printouts, reports, memos, forms of one kind or another, advertisements, brochures, notice boards and other static displays, public address systems, automated alarm systems and simple face-to-face conversations.

Most writers distinguish between ‘oneway’ methods, which do not anticipate a reply, and ‘two-way’ methods, which permit the exchange of information and views. Another common distinction is between ‘formal’ methods (usually this means those approved by management) and ‘informal’ (unofficial or unplanned) ones. This last distinction is important if you are analysing how a department actually works (gossip is very much part of the ‘informal’ system) but it is not very helpful as far as the guest-receptionist relationship is concerned, because it ought to be part of your job to add little extra personal touches to the formal check-in or check-out process anyway.

No one method of communication is an ideal combination of:

![]() Speed

Speed

![]() Cheapness

Cheapness

![]() Permanence

Permanence

![]() ‘Two way-ness’

‘Two way-ness’

![]() ‘Quality’ (i.e. the ability to convey subtle shades of meaning, feelings, attitudes, etc.)

‘Quality’ (i.e. the ability to convey subtle shades of meaning, feelings, attitudes, etc.)

The telephone, for instance, is quick, ‘two-way’ and reasonably inexpensive, but you have to make your own record of the conversation and misunderstandings are not uncommon. Letters are cheap and permanent, but they are not particularly quick, and they do not encourage ‘two-way’ communication. Fax and e-mail are fast, more ‘two-way’ than letters and more permanent than the telephone, but you need the right equipment at both ends. Forms arrange information systematically, but they can often seem rather cold and unfriendly. One of your tasks is to choose the most appropriate method of communication for the task in hand. The fact that we often do this without conscious thought does not lessen the importance of the decision.

The communication process is actually a rather complicated one. There are at least four stages, each of which presents its own problems.

1 The person who should initiate the process must perceive the need to transmit the information. This does not always happen, as frequent cries of ‘Oh, I forgot to tell you!’ demonstrate. Hotels often introduce simple message, amendment or report forms in order to overcome this problem.

2 Arranging the material in a form suitable for transmission can be difficult. Most of us have experienced difficulties in composing important letters, and trying to find the right form of words to console a guest who has suffered a serious loss is another example. Statistical information presents difficulties of its own for many employees: working out percentages is not everyone's strong point!

3 The information must then be transmitted. This often creates further problems, because most types of transmission equipment have limitations. Telephone lines can be bad, or handwriting illegible. Post can be delayed, or computer links break down. Guests, colleagues and managers can provide distractions, and the pile-up of work on your desk can create a ‘log jam’.

4 Even when the message does reach the recipient, it may not be fully understood because perceptions can vary from one individual to another. This can apply to the factual content of the message (arrival dates are unambiguous but departure dates aren't, which is why many hotels ask for the stay in nights). More seriously, the attitudes accompanying the communication may be misinterpreted. Well-meant advice can sound patronizing. One guest may see a smile as conciliatory, another may interpret that same smile as smug or superior. A lot depends upon his mood at the time: if he is tired and irritable (and guests who have travelled a long distance often are), then he is particularly liable to this kind of misinterpretation.

In theory, face-to-face conversation ought to be the most effective means of communication, because it is immediate and allows the maximum amount of information to ‘flow’ between the participants. You can hear your guest's words clearly, and you can also hear his tone of voice (without the distortion you sometimes get with the telephone) and see his accompanying facial expressions, bodily postures and tiny, give-away gestures. This is important, because you should be trying to gauge his state of mind. Is he hungry and impatient, or well fed and content? Is he really seriously upset about the fact that his bedside lamp doesn't work, or just making trouble for the sake of it? Is he telling the truth about that misplaced letter of confirmation?

However, because attitudes and feelings are easily communicated through what is called ‘non-verbal communication’ (expressions, tones of voice, posture, etc.), face-to-face communication can be dangerous. A bored and dissatisfied receptionist may say ‘Can I help you?’ in such a way that the guest obtains a clear message that she doesn't really want to do anything of the sort. Studies have shown that these non-verbal clues have about five times the effect of the verbal ones. In other words, our bored receptionist is likely to give an overall impression of incivility no matter how polite her actual words might seem to be. It is not so much what is said, but how it is said that counts.

Conclusion

The fact that ‘service’ depends so much upon interpersonal contact means that the way staff behave plays a particularly important part in determining service quality. Role theory tells us much the same thing because it implies that we consciously or unconsciously act or play a particular kind of role, and communication theory underlines this. The ‘dramaturgical’ approach described leads on naturally to a consideration of what are called ‘social skills’. The question is: how can we actually ‘project’ attitudes such as sympathy, helpfulness and sensitivity? We will consider this in our next chapter.

Assignments

1 How far do you think guest expectations in terms of physical facilities might differ between the Tudor and Pancontinental Hotels?

2 To what extent would their expectations differ as far as the intangible aspects of hospitality are concerned ?

3 How can a large and busy chain hotel with a high turnover of both guests and receptionists provide ‘personalized’ service?

4 To what extent do you think technology can be substituted for personal service?

5 Describe the various methods by which front office might communicate with guests before, during and after their stay, indicating their advantages and disadvantages and suggesting the circumstances in which each might be used.