STEP 6

PROTECT YOUR WELLBEING

Tayla Harris is one of the most recognisable players in the Australian Football Women's League (AFLW). She was an inaugural player with the Brisbane Lions when the competition started in 2017 and an all‐Australian representative in 2017 and 2018. After she transferred to Carlton in 2018, she became the leading goal‐kicker that year and the next and in 2021 she continued her career at Melbourne in the AFLW. She has also been a high‐performance boxer, having had eight professional bouts at the time of writing.

One of Tayla's strengths is her kicking. In a match against the Western Bulldogs in 2019, she powered into a trademark kick that was captured by photographer Michael Wilson. Tayla was in full flight, propelled off the ground by her strong action. When the photo went viral, Tayla became a target of online trolls and harassment that is hard to fathom. ‘It was totally unexpected,’ she said when I asked her about the incident. ‘I couldn't have imagined anyone would think anything other than “there's an athlete playing their sport”. I tried to understand it but couldn't. I found it very frustrating.

‘I decided that because it was totally unacceptable I had to respond. [Tayla retweeted the photograph with the comment, ‘Here's a pic of me at work … think about this before your derogatory comments, animals’]. I also did it because my biggest fear was that young girls seeing the negative comments would avoid or stop playing sport. I was okay with responding because the public support was amazing and powerful.

‘I have a very close circle of supporters. As soon as it happened, they did whatever it took to help me. I'm not afraid to ask for advice or suggestions. That meant as well as my closest supports I got some great advice from other people I respected. Because of that support from everyone, the situation became more uncomfortable than bad.’

Tayla's story offers lessons on many levels. The importance of established supports to nurture athletes’ wellbeing is paramount. The importance of seeking help is another. Her capacity to reframe the situation from bad to uncomfortable on the back of support also reflects how she managed her narrative through that time. The community support led to the creation of a statue of Tayla in mid kick that symbolised, among other things, the importance of respect — for women in general and for athletes simply plying their trade. It also symbolised the importance of respect on social media. Inappropriate, even toxic commentary on social media has become an additional layer of stress for many people, including athletes, as this medium has gained momentum over the past decade. ‘It doesn't matter if you're a man or a woman, young or old — everyone has a right to do what they love,’ Tayla said at the unveiling of the statue.

I have worked with athletes who have been abused on social media for their performances. Some comments have been crudely disrespectful, as in Tayla's case. Some threatening messages are from frustrated and angry gamblers who have lost money wagering on an event. Some supporters who are frustrated with an athlete's performance feel they have the right to abuse and threaten them. Such behaviour is totally unacceptable and should not be tolerated. It adds another stress that athletes have to deal with — another challenge to their wellbeing.

Tayla should be applauded for how she handled the situation, as well as how she managed her own wellbeing. But it never should have come to that. Sporting teams and bodies have started to do more to support people in this situation. In my opinion, this work has to continue and increase. The subject of athletes’ wellbeing has gained increased attention in recent times and should continue to be a priority.

No one is immune

The reality is that no one is immune to emotional, mental health or wellbeing challenges, certainly not high‐profile elite athletes or any person involved in sport. Proactively looking after their wellbeing and mental health should be an ongoing priority.

The positive human spirit can find strength even in seemingly dire circumstances. Challenges that feel insurmountable can be overcome. Having worked with many athletes through extremely difficult emotional situations, I have the utmost respect for their effort and capacity to deal with adversity and recover and return to strength. I know that many people draw inspiration from their stories.

Wellbeing enables exceptional positive personal and professional experiences. Nothing is as important as you — not a job, an exam mark or a relationship, not winning, not even sport itself. Drawing on positive spirit, as well as using supports and a range of other strategies, can help sustain wellbeing. From there, performance in any field is easier to maintain.

Performance does not grant immunity. Winning doesn't protect against wellbeing challenges either. Winning can actually add layers of stress, with increased external attention and scrutiny compounding the personal pressure athletes put on themselves to perform. ‘As an athlete I always felt like I wasn't good enough,’ Nicole Pratt admitted. ‘I didn't recognise the importance of celebrating. I was caught up in pushing on. For example, when I won my one and only WTA career title in India: it was a solid draw and a hard‐fought tournament win, but there was no one there to celebrate with. It should have been a great moment, but I felt horrible without anyone there to share it with. It was a bit hollow. That night after the win I spent in my room crying. From that experience I realised that sharing is more important than winning.’

Nicole's story speaks to the emotional toll that elite sport can take. Many athletes are relentless in their pursuit to perform, often at the cost of their own wellbeing. Wellbeing has to be prioritised above performance by all. Recognising that no one is immune to wellbeing challenges, managing them must be a daily task. Sometimes this is intuitive; at other times it has to be deliberately managed. Wellbeing cannot be taken for granted. It's a skill that should be prioritised. This chapter discusses some of the factors surrounding wellbeing and strategies to maintain it.

Find the positive

Sport creates many exciting and interesting opportunities for athletes and other people involved. It can foster and build wellbeing by creating lasting positive relationships and experiences that can be reflected on for years to come. Training with teammates or squad members, learning new skills or simply doing something they love to do are some elements that can make a sport enjoyable, even away from competition. A healthy sporting environment can also be a place to develop life skills and personal growth. This may be one reason why it has been suggested that athletes make great employees.

On managing wellbeing, finding positives in what you are doing is a good place to start. A positive doesn't have to be a huge achievement. It can be a small task. This is why I ask athletes to identify and record daily positives, as discussed in earlier steps. It's incredible how difficult this is for some people. But once they are able to recognise daily positives, they become more attuned to noticing small things they enjoy. They notice positives in others as well. This is different from gratitude, which we'll discuss later in the chapter. Examples of daily positives can include:

- did something well or enjoyed at training

- had a good chat with someone

- made a nice dinner

- complimented a teammate

- started a conversation with an athlete or coach I don't often speak with.

Keeping such a record doesn't need to be ongoing. It can be used intermittently to develop the habit of noticing positives and thinking positively. Noticing positives also contributes to building wellbeing hygiene. I see wellbeing hygiene as a product of developing protective mechanisms that contribute to sustaining wellbeing and enhancing resilience to deal with challenges through thinking positively and putting structures in place that protect wellbeing.

Person first, athlete second

Scott Draper experienced his share of challenges, both personal and sporting, as described in step 2 on resilience. These experiences contributed to his prioritising wellbeing. ‘If you have your life in order, it is so much easier to compete,’ he told me.

A consideration in sport, as well as other fields, is that wellbeing and mental health don't exist in isolation. It would be convenient to compartmentalise our lives, but the reality is that wellbeing and mental health exist within a larger dynamic system that all of us, including athletes, operate and exist within. Life and sport coexist, and it is difficult to block out one for the sake of the other.

Athletes are people first and are subject to the same wellbeing and mental health concerns as anyone else. Difficult relationships, family worries and other personal issues affect athletes just as they do everyone else, and these issues need to be recognised.

Many sports provide little or no financial return or security for athletes. As a result, many athletes have ‘dual careers’, studying or working while training and pursuing their sporting ambitions. In these circumstances, a high‐performing focus that exists in sport can carry over to other areas of life, which can be good but can also create additional pressure and layers of challenge. I have seen athletes thoroughly enjoy studying or holding down a job to balance their sport, but it can put an unsustainable pressure on them when they feel they have to do as well in that field as in their sport or the workload and demand from each is overwhelming.

A person can only spread themselves so far. In this situation athletes, coaches and supports must recognise that each individual experience should help the other. When it doesn't, changes need to be made. I am typically quite assertive on this. Wellbeing is not a space to be patient in. Training and performance can build slowly. The slightest hint of a wellbeing challenge needs to be treated as urgent. The person is more important than the sport. As I mentioned in step 4 on leadership, there have been times when I have called a crisis meeting late at night. I have learned to drop everything, and have done so many times, to try to prevent a difficult situation from escalating.

At times, sport can be a haven, a space in which to escape life's challenges. It may provide life lessons to foster emotional growth and positive wellbeing. On the other hand, a sporting environment can exaggerate any pre‐existing concerns or vulnerabilities and cause frustration and stress.

Recognising different factors that can impact wellbeing is one aspect to help manage this space. Some of these are listed here.

Athlete‐centred environments

An athlete‐centred environment is one that sees the athlete's wellbeing and personal development as equal to or more important than their performance. It prioritises the person over the sport. Coaching should incorporate working with the whole person, not just the athlete. This approach influences communication, decisions about training and a range of other factors. It guides thinking, behaviour and decisions or operations in a sport.

An athlete‐centred environment should be overt and observable, not just a philosophy to be discussed. In this way it can be evaluated and emphasised by all stakeholders in the organisation, including coaches, other staff and administrators, as well as the athletes. It is no different to a people‐first culture at a workplace or student‐focussed environment that encompasses social‐emotional learning at a school.

Look beyond the behaviour

When working with athletes on wellbeing and mental health issues, the broader picture needs to be considered. This encompasses reflecting on both the environment and the person. What is happening in the sporting environment that may be impacting wellbeing? What systems and processes are impacting wellbeing positively or negatively? What is happening in that person's life? What is impacting their emotions and behaviour? These are necessary questions.

Too often people focus on individuals regarding their wellbeing and mental health without considering the environment. This is unfair. Wellbeing concerns are not simply about the person. For example, if a sport has multiple wellbeing and mental health issues, the environment and system require thorough investigation and likely an overhaul. At times the environment may be fine; it may even support and assist the individual, yet they may still struggle emotionally. Understanding what is affecting their wellbeing, both positively and negatively, gives individuals and the organisation an important insight to assist in navigating people into a better mental space. Don't simply look at the person when considering wellbeing challenges. This insight helps explain why culture is so important, as discussed in step 5 on culture.

Poor behaviour in sportspeople can also reflect stress. ‘Look beyond the behaviour’ is advice I have long encouraged coaches to consider. Missing sessions, arriving late or underperforming may point to a deterioration in coping. At more severe levels, substance abuse and behavioural issues need to be addressed, but can also be a reflection that something more is going on. In these instances, both the behaviour and the emotional factors contributing to the behaviour must be addressed; otherwise repeat offences will likely occur. This does not excuse poor behaviour that clearly has consequences, more that, when addressing and dealing with poor behaviour, a deeper dive is often necessary.

Wellbeing and mental health

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as ‘a state of wellbeing in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’.2

This definition has evolved from a positive psychology framework where the capacity to flourish and thrive is assessed. This framework is distinct from historical medical models in which the absence of a mental health issue was itself associated with positive wellbeing. The WHO points out that mental health is more than just the absence of mental disorders.

Sport psychologist Carolina Lundqvist has noted that the construct of wellbeing is both multifaceted and complex and has been poorly understood and defined. She has suggested that ‘an increased understanding of wellbeing in athletes is desirable, as this information could potentially address aspects of competitive sports that constitute obstacles and facilitate athletes’ ability to flourish and use their full potential as both humans and athletes’.3

In a recent overview of mental health in elite sports, Lundqvist noted the ‘almost explosive growth in interest in investigation of mental health among athletes’.4 This has been stimulated in part by a global shift towards greater responsiveness on mental health issues in society overall. Lundqvist also noted that ‘wellbeing is increasingly adopted as an indicator of positive mental health’. She noted that single‐continuum models have been increasingly described to understand wellbeing and mental health and that in these models individuals typically move along a continuum:

- normal variations in mood, psychological and social activity

- normal emotional or behavioural reactions to life‐situations, such as being nervous or sad

- increased levels of psychological harm or injury, such as anxiety, reduced performance, difficulty concentrating and social withdrawal

- mental illness as a diagnosed clinical condition.

To be clear with regard to wellbeing and mental health, there is a distinct difference between a wellbeing concern and a more serious mental health condition. Often these can be confused. This is when professional advice and support is required. It's worth noting that it's normal to experience a range of emotions, including being sad or disappointed. There is a difference, as the model identified, between normal emotional reactions to poor performances, life events and a clinical mental health condition. Other models, such as the dual‐continuum model proposed by Keyes5, recognise that athletes may be flourishing with complete mental health or still functioning with incomplete mental health or illness. Having a mental health concern does not preclude a person from working or performing. I have worked with many high performers who continue to function in their role while they have mental health challenges.

Destigmatising wellbeing and mental health

In recent times, the greater preparedness of athletes with a global voice to speak publicly about mental health concerns has drawn necessary attention to mental health. It's so important to destigmatise discussion about mental health to encourage people to seek help. We need to get to a stage where athletes are as comfortable saying, ‘I'm struggling mentally at the moment’, as they are saying, ‘I've got a tight hamstring’. These conversations can prevent normal and temporary struggles from becoming more significant.

Athletes with a global profile who have spoken about mental health include tennis player Naomi Osaka, swimmer Michael Phelps and gymnast Simone Biles. This has contributed to creating an increased accountability on sports bodies to manage the overall care of athletes, including their mental health.

Incidence of wellbeing and mental health concerns in sport

Adolescence and early adulthood are stages of life that can be immensely enjoyable but can also bring many physical and emotional challenges. These years, of course, correspond almost perfectly with the most active period of an athlete's career.

There is some variation in the research about whether athletes experience a higher or lower incidence of mental health issues than the general population. This is understandable, as it is likely influenced by the sport, the culture and a range of other factors. From my experience, backed by data collected before and after interventions I have conducted or coordinated, I have seen squads and teams improve wellbeing and mental health over time when good wellbeing programs and cultures are in place.

A 2016 study suggested that on the basis of current evidence, elite athletes appeared to experience a broadly comparable risk of mental health concerns, such as depression and anxiety, to the general population.7 The authors found that greater risk of mental health issues might be experienced by athletes who were injured, were approaching or in retirement, or were experiencing performance difficulty. The study suggested there was a tendency towards greater vulnerability in sports involving a particularly lean body shape and in female athletes. Low social support was identified as a risk factor, highlighting the importance of formal and informal support networks.

Coping, both in and outside of performance, was reported to be important. Managing poor performances, dealing with performance‐related anxiety, managing injuries and social media content were some examples noted that impact coping. The authors also argued that assessment and management of mental health and wellbeing needs should be on par with that for physical needs.

Prevention is better than cure

Identifying and acting on a wellbeing concern early can prevent many future concerns. It is important to differentiate between experiencing symptoms associated with stress and a mental health diagnosis. Being aware that people may exhibit different symptoms can assist with early detection and intervention to stop a wellbeing concern becoming a clinical mental health issue. It also helps to differentiate between a more serious mental health concern and an understandable response to a short‐term situation.

Behaviours that may be symptoms or signs to look out for may include:

- more isolated or withdrawn than usual (not returning calls or messages)

- less motivated (being late, missing training, diminished performance at training)

- less interested in general or when speaking with others (giving one‐word or short answers)

- exhibiting lower self‐care (presenting more poorly than usual)

- being angrier or showing less energy than usual and seeming ‘flat’.

To assist people to look out for each other, I often consider behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms to be aware of and whether these are persistent, invasive and excessive. Given that athletes and coaches spend a lot of time together, keeping an eye out for these behaviours shouldn't be hard. They won't automatically signal a wellbeing or mental health issue, but a checking‐in conversation is always worthwhile.

Whether or not a person is experiencing wellbeing or mental health challenges, good wellbeing hygiene can be developed using some of the following strategies. These are only examples and by no means an exhaustive list.

Self‐appreciation, self‐permission, self‐acceptance and self‐compassion

Over a career, feeling that only the highest standards are acceptable every day is emotionally unsustainable. Nobody wins all the time. Even people expected to win might not. That's the nature of competition. Accepting that there are ups and downs both physically and emotionally can be empowering and a relief. It doesn't mean not striving for the best possible performance. It does mean developing self‐appreciation, self‐permission, self‐acceptance and self‐compassion.

Athletes are conditioned to strive constantly and absorb challenges, physical and emotional. They are conditioned to set high standards, to push through difficulties and to be hard on themselves. These are generally positive traits for an athlete. But while at times such an approach will serve performance well, emotionally it can create vulnerability, undermining wellbeing and in turn performance. Pushing through mental distress is not the same as pushing through physical discomfort to complete a challenging session, hard training block or tough competition. Because they are accustomed to pushing through discomfort, many athletes I have worked with take the same approach with their wellbeing. This is misguided.

In sport, selection and self‐validation can hinge on tiny margins of difference that have significant consequences. That's part of sport. But for an athlete to hitch their sense of wellbeing to such fine margins, although at times inevitable, is unhealthy.

To develop skills in the ‘selves’, consider appreciating effort, recognising enjoyment, and putting outcome and sport in context. The selves help athletes to be kind to themselves. They're about self‐care. They're also about being comfortable with being yourself mentally and physically. Appreciating relationships, opportunities and enriching experiences over and above outcome can help here. Adopting a learning approach can also help embrace the four selves. Striving for high achievement isn't often associated with complimenting oneself. It is typically more related to self‐deprecation or put‐downs. Self‐complimenting is important to sustain energy and is a part of this mindset.

Taking control of your wellbeing means not waiting for others to give you permission to do something that may benefit you. Too often athletes avoid self‐care until someone else gives them permission to take a break or do something emotionally nourishing. Certainly, at times this requires negotiation. You can't do anything you want at any time — like just not turning up. But asking for permission to miss a session or giving yourself permission to take a day off and do something that will help your wellbeing is important. It may be as simple as taking a lunch break or going for a walk! Prioritising time in each day for self‐care is part of this.

Self‐compassion has been a growing area of interest in sport. It is the compassion athletes direct towards themselves when faced with ‘painful’ or challenging experiences and is linked to adaptive psychological functioning and wellbeing. Negatively comparing themselves with other athletes (I call it the curse of comparison) is a common trap for athletes to fall into. These comparisons can relate to body image, development disparity or different opportunities. Its victims often become self‐conscious or self‐critical to their own detriment. Adopting a mastery or self‐referencing approaches and respecting individuality on a performance pathway can help to limit the curse of comparison. It can also foster self‐appreciation, self‐acceptance and self‐compassion, as well as enable self‐permission.

Gratitude and kindness

Being grateful is as relevant in the competitive environment of sport as it is in life. There is little doubt that being grateful can help wellbeing. There are numerous ways to show gratitude. There are also a variety of methods of coaching and building it.

Neurologically, expressing gratitude has been shown to contribute to releasing dopamine and serotonin, two important ‘feel good’ neurotransmitters. Showing gratitude has also been linked to the hypothalamus, which assists with regulating sleep, as well as a range of other functions. Gratitude is more than comparing yourself with people less fortunate. It's about recognising specific elements in your own life or circumstances to be grateful for.

On occasion, I have facilitated specific gratitude education and activity sessions for athletes. These have included identifying who has been helpful on a sporting journey and clearly communicating appreciation to that person. I have also been involved with organising athletes to send Christmas cards to supporters as a form of appreciation. Gratitude journals are a proven strategy for maintaining wellbeing. Keeping a record of what you are grateful for and writing letters of gratitude to bring even small positive experiences to the front of your mind can contribute to your wellbeing. A common activity is to record three things to be grateful for each day. This can be done for a week or a fortnight. It can be a one‐off or regularly repeated. The idea is to increase what a person identifies and notices around them.

Even saying ‘thank you’ as a form of gratitude has been associated with wellbeing benefits. Expressing gratitude can facilitate relationships and input from others. It can help keep perspective by ironing out the highs and lows. It can also contribute to feeling that there is a team involved in the journey.

Similarly, helping others has been shown to be positive for wellbeing, which is why athletes and sporting organisations can benefit from involvement with not‐for‐profit, community‐based activities and charitable organisations. Random acts of kindness, as well as formal pro‐social behaviour such as volunteering and supporting charities, have also been shown to benefit wellbeing. A gratitude journal is different from recognising daily positives, although there is clearly some overlap.

These concepts are about building wellbeing holistically. The focus of such activities, I believe, is on prevention and proactivity in developing wellbeing hygiene through positive emotional mindsets. Such activities, to be clear, are not the primary methodology for treating clinical depression and anxiety.

Journaling

As mentioned in step 2 on resilience, debriefing and reviewing can assist athletes in a number of ways. I have found journals and written records to be powerful tools for many athletes. I once had a follow‐up call from an athlete I had worked with some five years earlier. His career had stalled. The enquiry: ‘Do you still have the notes we made? I used them for a while but have lost them.’ Fortunately, I recalled the conversation and had kept the notes. The athlete agreed that it was time to update the notes based on his current circumstances. It's not too different from Jacqui Cooper looking at her 10‐year plan 10 times a day for 10 years. There are many well‐regarded athletes who are known for keeping some form of journals for personal or performance purposes.

Many athletes keep a journal for different purposes, such as goal setting, daily positives, gratitude or competition plans and reviews. It may be to record daily training to monitor and feel in control of performance. It may include quotes or mantras. It may be paper and pen or on an electronic device. A journal is a personal diary. It allows an athlete to debrief on their own and organise their thoughts and ideas. It can also help get them out of their head. Journals serve as a powerful reflection tool. Many athletes use and carry journals and diaries with them highlighting exceptional training sessions, work done and a range of other positive and learning features. I myself have kept diaries for many years to monitor my daily training, injuries, goals, events, health and thoughts. While not always for everyone or for every day, it is an underestimated tool on a sporting or any other journey.

Sport relationship and identity

For some athletes, their sport can feel like their whole life, rather than one part of it. This is understandable given that, for many athletes, engagement in their sport takes priority over most other activities. To achieve in most sports requires being fully absorbed. When commitment is high and the activity dominates most days for years on end, it is easy to become institutionalised within the sport. Stepping outside the bubble of their sport can help athletes to broaden their identity and ensure that institutionalisation doesn't occur.

In the worst case, it can feel as though without sport there is nothing. Sometimes this way of thinking requires external validation for recognition that sport is a part of life, rather than all that a person has in their life. This was evident in a Twitter comment posted by American gymnast Simone Biles during the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. During the competition her emotional challenges were laid bare for all to see. She was criticised by some, but she also received what she described as incredible support. She commented that the support she received helped her realise that she was more than her gymnastic achievements.10

Her comment provides some insight into why athletes can be vulnerable when things are not working. At times, people who commit so much time, energy and emotional investment in a pursuit can feel that their entire identity hinges on that activity. Clearly, their identity is defined not just by their sport, or by their success in the sport, even if it sometimes feels that way. Sport may be a significant and dominant part of what someone does, but it is about what they do, not who they are.

For Storm Sanders: ‘The biggest thing about wellbeing is to be able to open up to your team and to people you trust. It's so important to check in with yourself and with others. Even when my tennis got better, I always spoke to family back home. Even if you set aside your sport and results for only 10 minutes a day, it helps keep you grounded and that helps your consistency. I try to use down time to do things I enjoy.

‘After the semifinal at Wimbledon, after losing four match points and then losing the match, I thought I was still proud to have got those match points. I don't want to forget the journey. I try to recognise what's been good and really appreciate the journey.

‘Part of that is to make sure my identity is not just based on wins or losses. I try to make sure I have an identity beyond tennis and results. I have friends and other goals, so if I don't win a match I can keep going. I think if I felt like tennis was my whole and entire life, I would feel a lot more pressure to perform and wouldn't perform as well. It's easy to get stuck thinking you can only do one thing. It's important to dedicate time to yourself regardless of your results.

‘When I was injured, I found I could do other things. It helped me to see tennis as one chapter in my life, and not to ignore life after tennis. I realised it would not be my whole life. That probably happened because I had to start from zero again after a year out. I also recognised that you need support after big events, mainly because emotions run so high. It's so important to have the right people and supports around you.’

Storm and Simone, along with many other athletes, have learned how important it is to have an identity beyond sport. It takes pressure off performance and can ultimately help performance, even though that's not the priority.

Taking action

Cate Campbell is a four‐time Olympic swimmer with multiple medals to her credit. She is so highly regarded that she was selected as one of the Australian flagbearers (with basketballer Patty Mills) for the opening ceremony at Tokyo in 2021. With rumours swirling about whether the Tokyo 2020 Olympics would proceed in the midst of the COVID‐19 pandemic, Cate described the impact the uncertainty had on her in Vogue magazine. She received a message in March 2020 while at the supermarket that read ‘we're not going to Tokyo’. Cate admitted that ‘those words hit me with a physical force … My life suddenly seems meaningless — what now?’

Forced to stand still for the first time in her life, she decided, ‘to do something I have never done: to sit down, to stop moving, striving … I suddenly had the time and energy to pursue things I'd always wanted to do.’11 She learned that it's okay to stop and be still; 2020 taught her to swim more for the love of it, rather than out of fear.

Following her performance in Tokyo, Cate courageously and admirably announced that prior to the Games she had consulted her GP and a psychologist and had been prescribed anti‐depressant medication. She shared on Instagram her experience, noting that she wished she had got help sooner, and encouraged people to make mental health discussions more common. Her hope was that by sharing her story, it would reduce stigma and help to change people's perception of mental health.12

Cate's story reflects that medication is one tool, combined with counselling and other support mechanisms to assist a person to manage their emotions in challenging times. In the past the stigma, and concerns about medications, acted as a deterrent. Over the years medications have advanced incredibly. There are professionals specialising in this space to support and guide people through decisions about the best support path forward. It is much better to be proactive with managing wellbeing and begin intervention early (rather than waiting until a problem is exacerbated). This is reinforced by Cate with her reflection about reaching out for help sooner.

Help‐seeking

Help‐seeking is acknowledged as an essential component of wellbeing programs that advocate early intervention for athletes. It is a topic that should be incorporated into sporting programs and is a skill for individuals to build. A number of studies have been conducted to identify what assists athletes to seek help for mental health issues.

In sporting contexts, one obstacle to seeking help for wellbeing or mental health concerns is the cultural perception that the sporting world is for ‘mentally tough’ individuals. Athletes are conditioned to ‘push through’ physical pain barriers and deal with uncomfortable challenges.

In many sports, showing emotional or mental health vulnerabilities is too readily perceived as a sign of weakness. For high‐achieving athletes, who typically set high standards for themselves and are often put on a pedestal by the world outside, disappointment about feeling low can exaggerate the issue itself. Acknowledging emotional challenges can feel as though it compromises what an athlete thinks they should stand for. They unfairly judge themselves a failure for not always performing up to high expectations or for feeling anything other than great.

To enable help‐seeking to be viewed as part and parcel of high performance, such attitudes need to be recognised and dismissed, both by those around them and by the athlete themselves. Failure has to be redefined.

Mat Hayman began his professional cycling career in Europe when still a teenager. ‘I was 19, and it was hard. I was living in Poland and became very lonely and homesick. The only thing that made me happy was training and racing, but you don't train and race all day every day. I was very low mentally. The thing is, when you're down you don't want to do anything. Thankfully my mum and family recognised what was happening and pushed me to do something. I ended up joining a sketching and drawing class. It was totally outside my comfort zone but it helped me change my habits.’

When feeling low, Mat reached out to his family. They identified that he was unusually flat. They encouraged him to be proactive: to begin changing some poor habits that were driving him down. With their support, he said, ‘I began to turn things around, but they were scared there for a while.’

Mat makes an important point: reaching out for help is especially hard when a person is feeling low. Their energy level can be at its lowest, and their sense of embarrassment high, which is why many mental health problems such as anxiety and depression too often aren't managed until they are well advanced. It's also why prevention, help‐seeking and early intervention are so important. There are many ways to seek help and support such as in person, by phone, through self‐education or reaching out to family and friends. Reaching out in the smallest way can be of benefit.

The journey and narrative

Letting go of disappointing performances is a challenge for many high‐performing people. With so many variables influencing a performance, disappointments are inevitable. Results can't be changed over time. It's not uncommon for athletes to be unhappy if they come second. Dwelling on what could have been is more common than thinking I'm lucky I got second. A body of work in this space, called counterfactual thinking, provides some interesting insights. If a past performance is undermining wellbeing and the capacity to perform as a result of overwhelming disappointment, it has to be dealt with, rather than allowed to fester.

Putting a disappointing event, such as an injury or a poor performance, into context is difficult but necessary to help manage an athlete's wellbeing. As discussed in step 2 on resilience, pursuing a sporting career is rarely smooth sailing. There will be varying performances, and many twists and turns. Seeing a sporting experience as a journey can help to compartmentalise these events. A helicopter view helps athletes appreciate positive factors associated with their sport and success and not allow the challenges to dominate the narrative.

I often tell athletes that one single event does not define their journey. They are the authors of the experience, whether it's disappointing or gratifying. Some athletes are able to appreciate disappointments or even a poor performance, knowing they can learn and grow from them and they did all they could. Progress in sport is not linear. It's important to embrace all the experiences that contribute to the journey. The language you use to describe, talk about or remember an experience is a part of the narrative.

Managing a narrative helps you embrace an experience without judging it. An overall narrative is the culmination of a wide range of stories. How you see yourself in those stories and how you tell them can become defining. By effectively managing the narrative, you are the author of your own story. The events are what they are, but you decide how to interpret them. It may be happy or sad, or an incredible adventure with many ups and downs. Although the events cannot always be controlled, you can control and own the narrative.

None of this is to say that not winning or performing as desired or not gaining selection isn't gut‐wrenching, but rather that you should not allow it to define you.

Recovery, rest and sleep

Without adequate levels of recovery, rest and sleep, athletes will be vulnerable to a wide range of challenges, including injury, fatigue and emotional or mood challenges and fluctuations. Additionally, adequate sleep and rest facilitate alertness, capacity to absorb training loads and can help positive mood.

A comprehensive review of the sleep of athletes14 outlined the importance of promoting positive sleep behaviour and avoiding situations that present risks to sleep. Some sport‐related factors found to impact sleep include night competitions, high training loads and early morning training. Non‐sport factors affecting sleep included social demands, lifestyle choices and work or study commitments that many athletes also have. Positive sleep hygiene includes avoiding meals close to bedtime, adequate exposure to natural morning light, not lying awake in bed for an extended time, a relaxing bedtime routine and a good sleep environment that contains a cool, dark space without electronic devices and with minimal noise or distraction.

When discussing sleep with athletes, a point I often suggest is a pre‐bed routine. This involves allocating a generally consistent time to go to bed and a consistent routine for approximately 30 to 60 minutes prior to that time. The goal is to promote winding down and can include habits such as checking or confirming what is on the next day to feel organised, slowing down and relaxing, not eating and, at times, noting down anything that is on your mind so that once your head hits the pillow these thoughts do not surface and keep you awake. The aim is to reduce your worries and to avoid ruminating on them. When athletes are travelling, I also often discuss taking their own pillow and pillowcase. The familiar feel and scent can cue you into having a peaceful sleep.

Another challenge to falling asleep is worrying about not sleeping, as this can contribute to wakefulness. The original reason for not falling asleep or waking during the night can diminish in comparison to the anxiety about not sleeping. One way to counter this is to focus on the restorative capacity of deep rest. If you're not sleeping, then switching away from worrying and focussing on deep rest can have positive restoration benefits and enable a person to fall back asleep. Identifying a good sleep position, a relaxing breathing pattern and methods to clear your mind are possible strategies to adopt.Using downtime to rest and learning how to switch off physically and mentally can assist recovery and build sleep habits. Naturally, we are discussing general sleep habits and not specifically your sleep the night before a major competition. As many athletes will attest to, prioritising and building skill in managing rest, recovery and sleep will aid wellbeing and performance.

Cognitive behaviour therapy and thinking traps

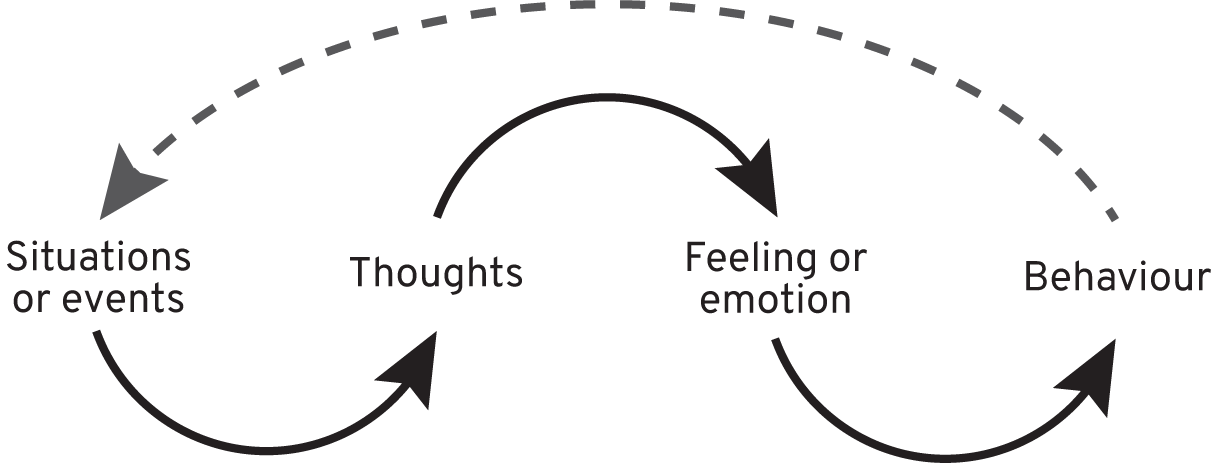

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has been described as a short‐term, skills‐focused approach to changing thoughts and behaviours. Over time, the term and the practice of CBT have emerged to represent the interaction between thoughts, emotions and behaviour.

Figure 6.1 is a model that is associated with cognitive behaviour therapy:

Figure 6.1: cognitive behaviour therapy model

By applying certain strategies, managing situations, thoughts and behaviour can help wellbeing and performance. Feelings and emotions are more difficult to manage, but no less important to acknowledge. Certainly, emotions can provide clues that help people manage their thoughts, behaviours and circumstances.

From this model, to manage wellbeing or performance a person can look to managing the situation or their environment, as well as their thoughts or behaviour. I often begin conversations on this topic by considering triggers, situations or events that occur around people and the resulting thoughts that may dominate their thinking. Challenging worries or doubts, maximising positive self‐talk and managing the overall narrative fall within the CBT model. Managing toxic negative self‐talk is a part of this process.

Helping athletes to manage ‘thinking traps’ is a CBT strategy to help wellbeing. Catastrophising, generalising, all‐or‐nothing or personalising are only some thinking traps that are commonplace. How these thoughts are managed is important in life and sport.

Disputing irrational thinking, reducing self‐consciousness and self‐criticism can also be managed through CBT strategies.

Environment, thinking and doing

In practical terms, I often consider managing wellbeing as managing the environment, thinking as well as actions or ‘doing’. An environment perspective considers both personal and sporting environments.

Here are a few questions that can be checked to monitor environment:

Environment at training

- What are relationships in the environment like?

- Does the training load need to be managed?

- What time, how often and where is training?

Environment away from training

- What are living circumstances like?

- How are relationships away from training?

- Are friends helpful and supportive of a sporting lifestyle?

- What demands do they face outside of high performance sport?

Here are a few strategies to manage thinking:

Thinking

- Identify specific worries and challenge them.

- Manage thinking traps.

- Consider what you are proud of.

- Consider what you are focussing on. Use self‐talk and neutral ‘let's see’ language when appropriate and be curious in your approach to situations, as discussed in step 3 on focus.

- Monitor and listen to warning signs, and be comfortable speaking about and being proactive in seeking support for in relation to wellbeing.

- Consider your SEAs — strengths, enjoyment and achievements. Record and reflect on these. Update the records routinely and get input from others to add to or confirm your own thoughts.

Here are a few questions to consider what you are doing:

Doing — non‐sport

- Who am I connecting with?

- What nature place do I enjoy?

- When is my personal time?

- What could I read?

- What could I watch?

- What could I listen to (such as music or podcasts)?

- What movement could I do (outside your sport)?

- What food could I enjoy?

- What am I remembering?

- What am I looking forward to?

- What project or hobby am I working on?

Doing — sport

- Can I do anything more at or for training?

- Do I need to do less at training?

- Who am I communicating and connecting with?

- Do I have too much on?

- What do I need to do from a lifestyle perspective to help my sport?

Reflecting on these questions can assist you in gaining insight and control and contribute to your wellbeing and performance. Considering what you are thinking and doing to help yourself and your situation is also relevant.

Mindfulness and ACT

Herb Elliott described it back when he was racing some 60 years ago. When possible, his pre‐race routine included just sitting under a tree to energise. This might have been an extension of his training base being conducted at Percy Cerutty's famed Portsea ‘Spartan’ camp. Portsea is a small town with a rugged ocean beach about 100 kilometres south of Melbourne. Back in 1960 it was an outpost of dirt roads, sand dunes and tea trees with myriad walking and running trails. To train there at that time would have meant an immersion in nature. Herb described that poetry, music, forests and solitude contributed to his spiritual strength. He emphasised that spirit, as much or more than physical conditioning, had to be stored up before a race — hence ‘sitting under a tree’ as part of his pre‐race preparation. Whether knowingly or unwittingly, Herb was practising mindfulness.

Mindfulness has been defined in a variety of ways, but is predominantly identified as a present‐moment, non‐judgemental awareness. While you are aware of internal stimuli (thoughts, feelings or physical/body sensations) and external stimuli (your immediate environment), a mindful approach means not trying to control or change them. Mindfulness evolved as a practice to use in general day‐to‐day life. In recent years, its application in sport settings has gained momentum, including for both personal and performance benefit.

A fundamental concept of mindfulness is that in the moment both past and future become irrelevant. All attention is directed towards the here and now. Internal and external stimuli, including thoughts, are recognised without judgement. For this reason, mindfulness has been linked to a flow state or as a strategy to achieve a flow state.

Another concept athletes can use to benefit wellbeing and performance is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). This concept combines mindfulness and acceptance skills to enhance psychological health by helping people develop a new relationship with challenging thoughts, feelings and emotions. Mindfulness‐Acceptance‐Commitment does not aim to change negative thoughts but to notice them and then allow them to pass, re‐directing attention and keeping an athlete's focus in the present.

Mindfulness is often used interchangeably with meditation. Meditation is a practice to train attention and awareness and is typically understood as a deliberate, formal activity. There are, however, many formal and informal ways to become more mindful. ‘Mindful eating’, ‘mindful walking’, ‘mindful breathing’ or ‘nature mindfulness’ are just some mindful activities. In my workshops with athletes, I have conducted a range of mindfulness exercises, including mindful eating, nature mindfulness and diaphragmatic breathing (more on this soon).

Mindful eating includes becoming more fully conscious of the flavour, texture and even scent of the food we eat. Too often we eat quickly, distractedly, on the go. Mindful eating means appreciating fully what we are eating. It invites us to slow down, and pay attention to the act of preparing and cooking food, as well as eating, including the taste sensations and nourishment it offers, enhancing the experience of eating. Even where the food has come from.

Nature mindfulness involves a conscious focus on the sky, trees, wind, temperature and landscape, becoming fully aware of nature and what is happening around us without judgement. In this way, nature can assist us to be fully absorbed in the present. I have encouraged athletes to watch clouds or tree branches in the wind or feel the sensation of the earth under their feet.

The relevance to sport of such activities is that they can help athletes to anchor themselves in the present and create a sense of calm. Don't worry about who is in the race or the heats yesterday or the final tomorrow. Let go of worries or distractions, and be fully absorbed in what it is you're doing now. Embrace the competition, the challenge, the opportunity. It doesn't mean you don't care about the opposition or tactics. Rather, you are more fully absorbed in the task at this moment, without the distraction of negative emotion.

Diaphragmatic breathing

Diaphragmatic breathing is one of the most effective exercises to assist people to manage their wellbeing and performance. It is a strategy that I teach regularly when working with athletes. It sounds so simple, but don't let the simplicity camouflage its significance or benefits.

Diaphragmatic breathing involves proactively engaging the diaphragm muscle that lies below the lungs and adjacent to the abdominal or stomach muscles. The diaphragm contracts and flattens on an inhale, creating a vacuum that helps pull air into the lungs. On an exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and assists in pushing air out of the lungs. In essence, on an inhale the diaphragm presses on the abdominal muscles, which can be observed to expand. On an exhale the abdominal muscles can be observed to contract inward towards the spine. Maintaining this pattern effectively when experiencing high demands for oxygen, fatigue and/or high levels of anxiety can be very challenging.

There are specific exercises to maintain effective diaphragm breathing, but the aim is for it to become almost instinctive. When done effectively, diaphragmatic breathing can be used away from an event to stimulate a calm or relaxed state, or in the lead‐up to or during competition.

Supports and mentors

Speaking about his sporting journey, Dave Andersen declared, ‘Support has been immense for me. I attribute my prolonged career to the support I've had. It helped me be a chameleon and adapt to the constant changes I experienced. And it wasn't just the people involved in the teams I was in but also my family, including my parents, brothers and sister. My wife Nerida has also been an enormous support. My first international contract was in Italy when I was 18. As a family we decided my brother Stewart would move over with me to help with the transition. It helped to have someone to talk to, and after crappy games to just chat and forget about it. We also did a lot of training together in extra sessions I did away from the team. A few years later, when I got a contract in Moscow, my other brother, Grant, came over and lived with me for a while.

‘As well as family, I worked on building a support team of professionals around me. I'd consult with them about sport and life, and they were vital. They shared the journey too, which added another positive layer. I could pick up the phone from anywhere in the world and call them and they would be there for me. They were always checking in on me as well, sharing the highs and lows.’

The research on athlete mentoring is limited, but one review of the impact of peer mentoring (mentoring from a teammate) suggested that peer‐mentored athletes were more satisfied with their sport experience personally and with their performance. These athletes were also more satisfied with team integration and ethics, and with training and instruction, compared with athletes who were not mentored. On this basis, the authors recommended that teams explore peer‐mentoring programs.17 In my own experience, athlete mentor programs have been enormously positive, both for mentees, and for the mentor.

Dave Andersen, of course, plays a traditional team sport, but Scott Draper also recognised the importance of supports on his journey in what is typically identified as an individual sport. ‘What helped me in my tennis was realising it is not an individual sport. I had a personal and a professional support team. They were a huge part of it for me on many levels.’ I put this question to many squads in sports such as swimming and athletics that are competed individually: ‘Is it an individual or team sport?’ It's a team sport. The benefits of a solid support network cannot be underestimated, and the earlier these are established in a sporting career, the better. While at times they evolve naturally, often they are created and managed carefully and deliberately. As Dave mentioned, they support and share the journey.

Wellbeing programs and data

With the increasing focus in recent years on athlete wellbeing and mental health, several recommendations and models have been put forward to maximise athlete wellbeing and minimise concerns. One such model recommends a four‐tier framework for supporting athlete mental health and wellbeing.18 The base of the model emphasises preventive components, including building mental health literacy, individual athlete development, and mental health and wellbeing screening and feedback.

It emphasises building cultures around acknowledging that to benefit both athlete wellbeing and performance, mental health needs are as important as physical needs. Such programs help athletes develop a range of self‐management skills to deal with psychological distress.

In my work in professional sporting environments, I advocate strongly for such programs to be integrated into the organisation alongside performance development. As a part of this process, I have conducted both unidimensional mental health assessments and multidimensional wellbeing screening that have incorporated assessment of mental health symptoms. I prefer using holistic wellbeing data that is multidimensional. This type of assessment considers and collects information on a wide range of topics. One reason for this is because when associated with variables such as engagement, resilience and positivity, wellbeing is viewed in the context of specific relevant topics, which can be informative. These topics all inter‐relate. Collecting data across a range of areas that impact wellbeing is also time‐efficient in programs that are typically time‐poor. This is one of the reasons I developed the Six‐Star Wellbeing and Engagement survey that has three versions: one for students in schools, one for staff in different environments, including coaches, and administrators and one for athletes.

Utilising data collection in a sporting group creates opportunities for coaching wellbeing topics with groups of any size. Data also creates a layer of accountability to organisations on topics that are difficult to accurately determine objectively. The data also enables specific staff, such as psychologists within the sporting organisation, to monitor wellbeing over the athlete's sporting journey. I have also used wellbeing and mental health screening tools to collect data for the purpose of working with coaches.

A wide range of possible topics that can be incorporated in a wellbeing program for sports, includes (in no particular order):

- sleep and rest

- balance

- mood and mental health

- resilience

- engagement

- communication

- supports and mentors

- help‐seeking

- relaxation

- mindfulness

- optimism and positivity.

Of course, such programs are more effective when supported by coaches and administrators. Coaches and support staff can be co‐facilitators as well as recipients of these educational initiatives.

Wellbeing checklist

As outlined, when working with sporting teams and bodies, I advocate integrating wellbeing and mental health work into athlete programs, just as physical and mental skills performance training should be integrated.

I have created a 10‐point checklist to guide this process:

- Commit to the wellbeing of your sporting organisation by prioritising the wellbeing and mental health of its people — athletes, coaches and other staff. This includes selecting coaches and staff who embrace an athlete‐centred approach. As part of this process, set wellbeing goals.

- Allocate specific professional staff to monitoring and working on wellbeing of athletes and staff.

- Screen all athletes and coaching/support staff on wellbeing, utilising a multidimensional tool at appropriate times in the year such as pre‐season and in‐season. If using daily or weekly apps that incorporate wellbeing factors, ensure that the data is used effectively and that appropriate staff are alerted when variations are detected. It can be very frustrating for athletes and staff when data is collected but not followed up on.

- Provide whole‐team or small‐group feedback on de‐identified wellbeing data. Proactively initiate wellbeing check‐in meetings with individuals.

- Look out for warning signs, and follow up with potentially vulnerable individuals.

- Allocate time in the training program to discuss and coach wellbeing and mental health.

- Refer to specific professionals or mental health service providers when appropriate. Commit funding to support this process and ensure that finances are not a barrier to obtaining support. Build relationships with these service providers to optimise internal and external referral opportunities.

- Be flexible within the environment to enable personal emotional demands to be met, such as players having time away from training, if necessary. This may be as short as missing one or two sessions or half a day to longer breaks if needed.

- Identify specific vulnerable times, such as at induction, exit or retirement, injury, form slumps, moving away from home, extended down time such as after major competition or surgery, transition away from sport, post non‐selection phases or other specific circumstances.

- Review organisation systems and practices as a whole and their impact on wellbeing of people across the organisation.

Building an environment of positive wellbeing, including good support structures, clear communication channels and prioritising the person above the athlete can have significant positive benefits on people and performance. Keep in mind that when done well, this can be done in a time‐efficient manner and need not be a time consuming and laborious practice.

Summary

Coaches and staff working in teams and sporting organisations have a responsibility to prioritise proactive wellbeing education. An athlete‐centred environment sees the athlete as a whole person. At the same time, athletes must take responsibility for their own wellbeing and be comfortable seeking help when needed. Recognising that wellbeing can sustain energy and motivation to drive performance also has to be considered.

There are many strategies to manage and maintain wellbeing. These should be understood and integrated into the thinking and practices of athletes, coaches and other staff. Data collection can help sporting organisations in a variety of ways. Most importantly, taking a preventive and proactive approach to wellbeing should be prioritised above all else. The person is always more important than the performance. In line with this philosophy, be sure that organisations, teams and individuals set wellbeing goals and do not sacrifice these for performance goals.