STEP 5

FOSTER YOUR CULTURE

Australia's swimming team made history at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics when it won more gold medals than any previous Australian Olympic swimming team. The Dolphins won 21 medals in Tokyo (including open water), nine of them gold. This was a far cry from the 2012 London Olympics where Australia had its worst swimming team performance, with 10 medals overall and only the women's 4x100 relay team winning gold. The performance raises curiosity about the team's rise at Tokyo.

Culture in practice

When Rohan Taylor was appointed as head coach, replacing Jacco Verhaeren, his clear focus was to continue an overt and very deliberate culture build. Rohan had discussed this with Jacco in the transition to his 2020 appointment, in the midst of the COVID pandemic and only 12 months before Tokyo was scheduled to take place. ‘From my experience in a previous role as head coach at Nunawading Swimming Club in Melbourne, I knew the importance of culture,’ he told me when I interviewed him after Tokyo. ‘I took lessons I learned from there to the Dolphins.

‘To begin with I looked back to London, when the team's culture had been labelled poor. So I asked myself, what is culture? I see it as a living environment. What people see, feel and hear. It's the collective behaviours of people. I realised that historically there had been a focus on values, but not on behaviour. In London there were also a lot of silos due to an overemphasis on independence.’

Rohan emphasised three factors for the Dolphins in the lead‐up to London. ‘Early into the role I worked with the athlete‐and‐coach leadership group and we discussed which practical examples of athlete behaviours we wanted to foster.’ The discussion was based on a premise of three areas he had determined to emphasise in the culture build: (1) Recognise the core reason we are here — to perform; (2) Understand that each person's behaviour influences the rest of the team; (3) Central to this change was athletes’ buying into the culture and wanting to do things for the team rather than doing things because they had no choice.’

Trust and relationships were a priority. ‘I felt that, historically, people only understood the first of the three principles. The personal relationships hadn't been there when they needed to. I emphasised that supporting each other mattered most. This level of investment is necessary should pressure start to derail performance.

‘I didn't want to throw out or change the values that were in place. I aimed to align existing values (courage, excellence and unity) with the three principles I was introducing. Courage related to influencing others and respecting their individuality. Excellence related to preparing to the best of your ability. Unity was about recognising others, regardless of their performance. Unity was the fabric.’

When he took on the role as head coach, one thing that Rohan also wanted to create was a ‘legacy statement’. He reflected on a time when he had done some swimming coaching for the Hawthorn AFL team between 2005 and 2009. A quote he saw in the elevator at the club made a lasting impression on him. It read: ‘If you embrace Hawthorn, Hawthorn will embrace you.’ Drawing from that experience, in a coach‐and‐athlete leadership meeting in his new role he raised the idea of a legacy statement and relayed the story of the impact the Hawthorn declaration had made on him. After some discussion, the group came up with their own statement: ‘We make each other better.’

‘I wanted people to have something they could readily check their behaviour against.’ The statement was on all the slides used in team meetings and referred to regularly.

A key aspect of the culture build was acknowledging positive behaviours that aligned with the three principles. Highlighting what was working, what was good and fun was important. ‘I didn't want to wait until people stuffed up to highlight what we were striving for,’ Rohan said.

Following the explicit work on culture, examples of positive behaviours arose almost immediately. Squad members at a training camp who had finished a session jumped into another lane to help other swimmers finish their session. At the games, after a medal swim, Kaylee McKeown didn't have her team runners with her. A message went up to the stands from pool deck asking anyone wearing a size nine shoe to get down ASAP. ‘About five people jumped up to help,’ Rohan recalled proudly.

This is a summary of the steps Rohan described that he took as part of the culture build:

- He sorted out small things quickly, before they morphed into big things.

- He conducted fortnightly leadership meetings with athletes and coaches from early in the year.

- He considered the coach team for Tokyo carefully. ‘They had to have at least one athlete on the team, and they had to be experienced. This helped the relationship piece.’ He recognised the risk of younger, less‐experienced coaches focusing on their own athlete's needs at the expense of the whole team.

- He appointed an experienced senior assistant coach to help him.

- On arrival at Tokyo, he inducted the whole group into the venues, facilities and support structures.

- On their first visit to the pool, he arranged for the team to perform a chant on pool deck as a sign of unity in front of others.

- He designed the team's area to feel like a home away from home.

- At the pre‐departure camp at Tokyo, he reinforced positive behaviours and reflected on why the team were well prepared.

- In Tokyo he conducted routine check‐ins every morning with athletes and coaches. This typically took 30 minutes, but ‘if needed I was prepared to give more time to stay and have a conversation. It wasn't token’.

- He proactively sought out individuals identified as possibly being vulnerable.

The proactive emphasis continued to be practised after the Games in the form of a specific debriefing. This debrief format started after the 2018 Commonwealth Games. That competition, the Pan Pacific Games and the world championships were all debriefed with an emphasis on opportunities for future action noted. That information was used to assist the build‐up to Tokyo. The specific debrief from Tokyo included two opportunities: to ‘protect what we know works’ and to ‘apply our learning and experience to Paris in 2024’.

There was one major point regarding culture that Rohan was determined to highlight. ‘We wanted people to feel they were part of a great experience, regardless of performance. We didn't want people looking back at events like the Olympic Games and not have great memories as their dominant reflection.’ Simply by using the word ‘we’ rather than ‘I’, Rohan showed he was living the values and behaviours he encouraged.

Evidence of the successful culture build was reflected in performance. ‘The historical data leads us to anticipate that medallists are most likely to come from the top five ranked swimmers going into the meet,’ Rohan explained. ‘At London and Rio we had a conversion rate of top five ranked swimmers to medals of about 30 per cent. At Tokyo, we were able to shift that conversion to about 68 per cent. I attribute that to a wide range of factors predominantly based on the culture shift.’

So when watching the Australian Swimming Team or many other teams and athletes on screens, look beyond the performance to what lies behind it. Culture work is reflected in how coaches and athletes interact with each other and external stakeholders. It is reflected in how they hold themselves in times of inevitable challenges and losses, as well as positive performances.

Rohan's story reminds us that performance does not exist in a vacuum. It is founded on a wide range of influences that make up a team's environment and culture. Some of those influences are self‐evident but those that aren't are no less vital. Culture is an important cog in the performance mindset.

Thinking, decisions and behaviour

I like to view culture informally as the ‘personality’ or vibe of an organisation, be it sporting, corporate, educational, not‐for‐profit or governmental. It can also reflect what an organisation stands for, what matters most. Culture is often viewed as a shared pattern of behaviours, beliefs and values understood by organisation members. They impact a wide range of factors such as creativity, learning, thinking and decision making. As I discuss with groups when working in this space, effective culture should guide thinking, decisions and behaviour.

More formally, culture has been defined as ‘the social and psychological environment that maximises individual and team ability to achieve success’1 and as ‘a shared pattern of assumptions that guide standards and expectations in performance and behaviour’.2

Viewed from a structural perspective, culture can include a vision, a mission statement, values, purpose, priorities and behaviours. The range of terminology used when discussing or building a culture can be confusing, but the important thing to remember is that organisations are clear on what they are building and the language or narrative around it. Good cultures are sustained on processes being integrated into structures, communication channels and operations. It also involves all stakeholders being clear on the terminology and how it applies to the organisation and to them.

In sport, one interesting nuance related to culture is creating a single representative team out of individuals who may typically live in different cities and compete against each other. Track and field and swimming teams are two examples. Individuals from national soccer, netball, hockey and basketball teams, too, may compete against one another from week to week and unite only briefly before competing as a single team against other states or countries. Establishing a lasting culture in these circumstances can be challenging. This is in contrast to teams and squads that train and compete together on a weekly basis and compete seasonally.

Regardless of how a team is established, a strong and supportive culture is a competitive advantage, so I recommend that its development be by design rather than by default.

Looking back on his Paris–Roubaix victory, Mat Hayman reflected, ‘Special things happen to special teams. Knowing how supportive everyone was as a group was special. It was a great team for two years leading into that race. We were underdogs but a very close‐knit unit, and that helped me and was the special part.’

Sam Mitchell also believes that culture is vital to team success. ‘Most people are a reflection of their environment and perform at a level that parallels that environment.’

There is little doubt that individuals in teams and organisations feed off the culture of which they are a part. Yes, individuals contribute to culture, but the impact of culture on people cannot be overestimated.

High‐performance environments

Culture is one component of an environment. One model identifies four components essential to a high‐performance environment.3 These are:

- leadership (vision, support, challenge)

- performance enablers (information, instruments, incentives)

- people (attitudes, behaviours, capacity)

- culture (achievement, wellbeing, innovation and internal processes).

The authors recommended that practitioners working in the high‐performance and culture space take a holistic view and consider coaching leaders, facilitating performance enablers, engaging people and shaping cultural change in order to impact the whole environment. Their findings supported the contention that ‘a performance environment that is created in elite sports teams is equally as important as the people performing within it’.

I have always advocated for organisational structure as a source of competitive advantage in a sporting environment. What positions exist within such a structure, and who holds them? For example, is there a person responsible for culture development and management, or does that role fall to the coach? Is it a dual‐management role? Is there a leadership group of athletes who actively support the culture? Is data related to culture collected? What funds are directed towards staff capable of establishing a high‐performance culture? If a person is identified as highly capable, is a position created for them within the structure? These questions remind us that many factors need to be considered if structure is to provide a competitive advantage.

Nicole Pratt reflected that, ‘Environment is incredibly important. It breeds positive culture. I craved to be in a world‐class environment. I went from being a country kid to the Australian Institute of Sport, and that was really stimulating. Later I moved to the USA, to Harvard, and that environment was incredibly positive. There was recognition that all the athletes were doing something amazing. At times, in Australia I felt that being ranked 30 in the world was not recognised, but in the US at the time everyone thought it was amazing. That gave me breathing room, because what I was doing was celebrated and I took joy in what I was doing there. I had a real sense of belonging in that environment. After being a top‐ranked junior, my senior ranking was 340. After two years in the Harvard environment, I got to 140. Then I moved to Orlando, another great environment, and I progressed to 35. Both US environments had a culture of excellence, positives and a process focus that enabled everyone to achieve what they were capable of. It helped my career progression.’

These positive environments were one reason Nicole loved playing for her country. It was a different experience from that of being an individual on the grinding tennis tour. ‘Playing Fed Cup and at the Olympics was always a priority because I wanted to strive to be a national representative. I played my best tennis in those environments. I was highly charged and emotionally invested. When we played Colombia in Wollongong, we were down 1–2 and I hadn't played a match yet. Fifteen minutes before the last singles, Evonne Goolagong Cawley told me I was playing. It meant so much to me that even with limited preparation I went out there and won. Australia went on to win the doubles and the tie. It was an amazing experience, similar to the Olympics.’

Nicole's story is one of many that support the view that a healthy environment and culture can be a uniting and driving force that contributes to motivation, performance, engagement, positive experiences and personal growth.

Individual athlete and coach influence on culture

During his basketball career, Dave Andersen was part of no fewer than 22 national championship–winning teams in a list of countries that included Italy, Russia, Spain, France and Australia. With only five players on court at a time and squads of about 12 in a season, one person's impact on a team's culture can be significant. ‘I had a goal in every team I played for to be the “glue‐guy”,’ Dave recalls. ‘My mother was from England and my father was Danish, and I was born and raised in Australia, so it was bred into me to be culturally open‐minded. So when there were people from several nationalities in one team, I always deliberately tried to get them working together so we were all on the same page and it definitely helped.’

This may be one of the reasons why NBL team Melbourne United called Dave and re‐rostered him as a backup player just before the final series during a COVID‐impacted 2021 season. As it turned out, he didn't get court time in that final series, but he was at every training session and on the bench for every game, educating and supporting. So his 22nd and final championship was won without any court time. Such was the value of the glue‐guy.

In a 2010 study, researcher Peter Schroeder investigated how much team improvement was related to (a) a change in team culture and (b) the leadership behaviours inculcated by coaches in this process.4 He interviewed 10 NCAA Division One head coaches who had guided previously unsuccessful teams to championship level within five years. He found that ‘coaches started the cultural change process by creating core sets of values specific to their teams. To ingrain these values, coaches taught them with several tactics, recruited athletes who would embrace team values, and “punished” and rewarded consistent with the values’.

Cultural change was achieved reasonably quickly, in most cases by the third year. This fits with my own experience. Intent to build a culture is essential, along with investment in resources. Certainly, I have seen culture change quite rapidly when leaders have positive intent, have skills and resources and are united in their efforts. In my experience, positive culture change can occur as rapidly as across one or two seasons. Rohan at Swimming Australia is testament to this.

This study also identified two environmental effects on team cultural change. Some environments created an ‘aura’ that heightened the importance of team culture, which meant coaches did not have to spend as much time helping athletes understand and adhere to core values; hence the environment contributed to rewarding the values. But in environments that didn't have the resources to foster team culture, coaches had to spend much more time defining and teaching core values. These environments didn't reinforce core values, and in some instances even diminished their importance.

This study reflected the importance of valuing culture across an organisation. When all parties, from the boardroom to the last selected athlete to support staff, understand their influence on culture, everyone benefits and performance improves.

As athletes become more mature, appreciating and understanding their influence and impact on the environment and culture is of relevance. Engaging with their environment in a positive way to maximise the resources available to them can assist progress. Creating their own small positive sub‐cultures with supports, family and friends within the larger environment they are part of can also be of benefit. It is part of recognising reciprocal influence, a concept modelled by esteemed psychologist, Albert Bandura and his work on reciprocal determinism. The model outlines that psychological functioning involves continuous reciprocal interaction between behavioural, cognitive and environmental influences.5 Reciprocal influence acknowledges that people both influence and are impacted by the environment and culture they are in.

Cultural consistency

The study mentioned earlier confirms the importance of resources and broader buy‐in to building and sustaining culture. I have observed sports in which administrative staff force particular organisational values onto coaches and players. This approach is fraught with danger, since the values developed by organisational staff may have minimal application for competitive athletes. In addition, values must have ‘behavioural definitions’ associated with them that can be attached to on‐ and off‐field performance.

In my experience, values must be shared across an organisation in a way that allows specific behaviours to be adapted to suit different areas, including the athletes and coaches. This means the entire organisation will operate according to consistent cultural values. Each part of an organisation, including coaches and athletes, not only is accountable to the whole but grows in response to shared values with specific and differing codes of behaviour to them. This facilitates alignment, with people across an organisation being on the same page and directing their energy towards a common goal. Of course, this may not always be an option, but it's a model worth considering.

The finding from this study on effective emotional management supports a broader concept embraced by some sport teams and adapted from corporate environments: psychological safety.

Psychological safety

In 1999, when Amy Edmondson, Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, published a paper titled ‘Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams’, it is unlikely she would have known the ripple effect her study would have.7 She defined psychological safety as ‘a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’. Her research was based on an investigation of 51 small teams within a large manufacturer of office furniture that, at the time, had about 5000 employees. Her findings led her to conclude that a combination of structural and interpersonal characteristics influenced learning and performance in teams.

Structural features consisted of ‘a clear and compelling goal, an enabling team design (including context support such as adequate resources, information and rewards), along with team leader behaviour such as coaching and direction setting’. Learning involved seeking feedback, discussing errors and using this information to improve. Interestingly, and overlapping with sport, Edmondson noted the need for learning in teams as increasingly critical due to the growing complexity in fast‐paced environments that requires learning behaviour to make sense of what is happening and to take action.

Edmondson also noted that team psychological safety is distinct from individual psychological safety. Team psychological safety alleviates concern about the reactions of others and promotes a team's willingness to point out and learn from errors. Team members are willing to speak‐up about errors if they feel they will not be rejected by the team and that the team is capable of using the new information to improve.

About a dozen years after the publication of Edmondson's work, Google embarked on a similar assignment: to identify what made their best internal teams effective. ‘Project Aristotle’ reflected Aristotle's aphorism that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Over three years researchers analysed 180 teams from engineering and sales. Their findings concluded that the most important ingredient of success was how teams worked together and that psychological safety was paramount. Other important factors were dependability, structure and clarity, meaning and impact.

Edmondson's and Google's work highlighted the importance of psychological safety to culture. Since then, emotional intelligence has also been highlighted as assisting the promotion of psychological safety.

Learn and grow

Athletes spend countless hours training physically. Therefore, it is inevitable that, barring injury, they'll develop and improve in that way. The challenge is the rate of improvement. The goal is to steepen the development curve over time. Yes, training harder, better resources and a range of other conditions contribute, but an often‐overlooked ingredient to shift the rate of improvement is the capacity to grow and learn faster. It is less about the shiny new facilities and more about coaching competence and a culture that contributes to growth. Another important element is engagement. And positive culture enhances engagement, which in turn enhances learning. Work plus engagement results in higher and faster development. In essence good cultures embrace and create a learning environment. The learning applies to all members of an organisation.

To assist fast‐track growth, at times I have conducted assessments on athletes and coaches to identify preferred learning styles. This information can help coaches to coach better and help athletes to contribute to and engage in their learning. Some people learn better by reading, others by watching and some by doing. Taking such considerations into account only enhances the growth and experience of athletes and coaches. New Zealand educator Neil Fleming has researched how kinaesthetic, visual, aural and read/write are learning styles that can be adapted to maximise the benefits of coaching and, in turn, athletes.8

Effective cultures and learning environments balance individual and collective needs well, including catering for a wide variety of approaches to learning.

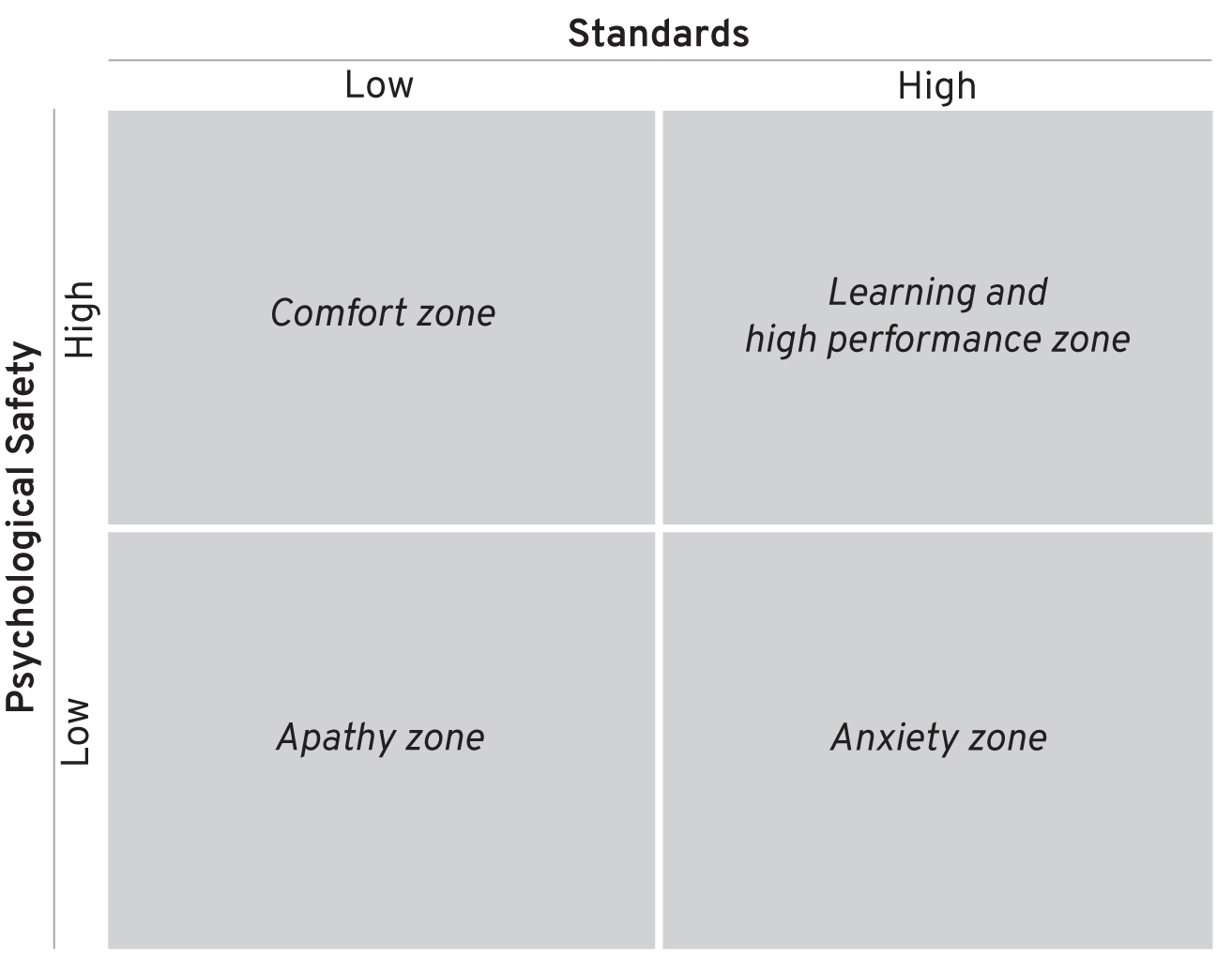

In 2008, Amy Edmondson expanded her work on psychological safety by presenting a model that incorporated a ‘learning zone’.9 She discusses this further in her book, The Fearless Organization.10 Within her model, the learning zone occurs when high psychological safety and high standards combine. In contrast, an anxiety zone evolves from the interaction between high standards with low psychological safety (see figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1: psychological safety and performance standards

Source: Amy Edmondson, The Fearless Organization (Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, 2018)

Edmondson also differentiates between execution as efficiency and execution as learning.

- Efficiency includes leaders providing answers, feedback being one way, and staff asking questions when unsure, with problem solving rare.

- Learning involves leaders setting direction and articulating the mission, feedback being two way, and problem solving being constant on the basis of information provided.

It becomes apparent that creating a learning environment is important for success over the long haul. This aligns well with learning in sport, considering the length of time it takes to be able to perform consistently at a high level. It also highlights the importance of a learning environment to be ingrained in the culture of sport. Too often the time pressure for results creates an environment where people are predominantly told, which in turn becomes counter‐productive to both culture and performance.

Emotional intelligence

In sporting environments, psychological safety can be thought of as a cultural variable and emotional intelligence as a quality that contributes to it. In many environments I have worked in, both coaches and athletes have had emotional intelligence assessments and education, either in groups or one‐to‐one. Emotional intelligence helps groups and teams who have to work together in often unusual and unpredictable circumstances. Teams also usually contain a wide variety of personalities, and emotional intelligence encourages empathy, understanding and respect of others, which contributes to a positive culture.

As a concept, emotional intelligence was popularised by Daniel Goleman, who has written extensively on the topic. His early work in this space began with his book Emotional Intelligence: why it can matter more than IQ, which was published in 1996.12 I have often used emotional intelligence as a topic to assist the personal development of both athletes and coaches in sport, as well as in corporate environments. Emotional intelligence can be coached and developed in athletes either directly or indirectly and benefits both personal interaction as well as culture and performance.

In my experience, psychological safety and emotional intelligence are both vital to culture. Emotional intelligence skills, such as effective communication, empathy, stress management and being open minded also contribute to psychological safety.

Relationships and communication

Effective communication and relationships are a cornerstone of a positive culture. They bring to life and sustain any values and behaviours as well as enable conversations and interaction to thrive. I often consider relationships in sporting environments as being either personal or performance based, as mentioned earlier. The stronger personal relationships are, the more thorough performance conversations can be. In turn, relationships, are built on a foundation of effective communication and positive experiences built over time. With strong personal relationships, however, one has to be sure not to be a ‘yes’ person and fail to provide honest feedback when necessary. There are many examples of successful sportspeople being surrounded by ‘yes’ people who want to be associated with them and avoid being honest for fear of the consequences. Strong cultures enable honest and direct communication without fear of repercussion.

Considering the variation of personalities, life experiences, ages and interpersonal skills people have, communication cannot be taken for granted. Good cultures are sensitive to these variations and establish processes to facilitate effective and appropriate communication education and channels. From a practical perspective, nurturing communication and relationships within squads and teams, as well as between athletes and coaches, can be done through designated activities and high‐level coaching practices. Such activities may be social and as simple as sharing meals or investing in a variety of tasks, including playing non‐specific games, having mentor and buddy systems, using small groups for different activities or allowing time for individuals to get to know each other better. Bringing emotional intelligence and social sensitivity to tasks can also help. As discussed in step 4 on leadership, it is not just what is done but how it is done that matters.

Additionally, specific education on communication and relationships can benefit individuals in squads and teams. There are a wide variety of avenues to enable this, depending on a range of factors including age, level or time together as a group. In sporting environments, understanding how to give and receive direct feedback is of utmost importance as the next challenge is always just around the corner. One aspect of this education should encompass providing feedback on behaviour, as distinct from on the person. Timing is another relevant aspect of providing feedback. Whether feedback should be in a group or individual environment also has to be considered. Tone, volume and language used are typical ingredients of communication education. Another consideration: is it assertive, aggressive or passive? Is it clear? Is there follow‐up?

Good communication and strong relationships enable athletes to be comfortable with acknowledging vulnerabilities and admitting errors that are a natural part of any sporting performance. Being able to put your hand up and accept responsibility for errors without feeling judged either by yourself or by others is powerful. Emotional intelligence and psychological safety encourage this openness, which is why they are important elements in effective cultures of all kinds and in sport specifically. It doesn't mean that all team members become best friends, but it does confirm the benefits of knowing the person as well as the performer.

As Garth Tander developed his driving skills, he also developed his leadership and understanding of the importance of culture. It is likely his appreciation of culture is another factor that enhanced his performance. ‘Team culture is so important because the individuals that make up the team are so varied. As I developed, I realised the need to respect and appreciate differences in people and other people's roles. I went from being young and brash and not appreciating others who helped me to being someone who did. As my career progressed, I learned to build personal relationships across the team with different staff. I asked them about personal interests to develop a deeper and more genuine connection. I realised it's really important to show appreciation for the people you go into battle with. Once a good culture is embedded and lived there is more harmony and efficiency. There are also fewer internal challenges and distractions. It also helps communication and avoids wasting time on things that don't help winning.

‘When I was doing high‐level physical training, if I'd had to do it on my own, I wouldn't have worked as hard as I needed to, but when I was training with others in a small‐group environment it was both more enjoyable and a better quality. It was a healthy competitive environment that helped me learn to push myself way harder. And it gave me a goal and enjoyment beyond racing.’

Individuals coming together in squads or team sports are there because they can perform, but Garth reminds us people can learn to appreciate others and that everyone contributes to a culture. A group performs better if there is a culture in which appreciation and gratitude are articulated and not taken for granted. Coaches and facilitators play an important role here to initiate conversations and foster relationships, particularly with junior athletes, which also contributes to the team's wellbeing.

In my own practice, I invite people to consider how they come across to others, as well as what formal and informal opportunities there are for communication and relationships to develop. At times I also conduct brief communication surveys that encourage reflection on the impact of different communication styles, such as predominantly assertive, positive, fun and jokey, or more serious. The key is to be aware of different communication styles and how one person's communication style impacts relationships and the culture.

Mastery climate

The concept of a mastery climate has its origins in the achievement goal theory that differentiates between an athlete's task and ego focus, which is discussed in step 1 on motivation. A mastery climate is characterised by learning and mastering skills and emphasises maximising effort or trying to do one's best. It goes without saying that sports environments are highly focused on outcome — athletes exist to win. However, an overemphasis on performance outcome to the detriment of mastery can have negative consequences.

The notion that a perceived mastery climate increases enjoyment and a belief that effort leads to achievement was identified in an early study from the 1990s with 105 basketball players from 9 varsity teams.16 This was further supported in a study with a small number of elite winter Olympic athletes. These athletes were high in task focus and moderate‐to‐high on ego, but felt the climate should have an emphasis on mastery and be accepting and caring to enable them to maximise success. The athletes also emphasised the importance of the coach as the creator of the climate.17

Emphasising mastery does not mean outcomes and results are set aside. Athletes and coaches know too well performance demands, and at times outcomes will be front‐of‐mind. Outcome goals and focus are often strong motivators. A mastery climate is about the day‐to‐day atmosphere around these outcomes. It embraces all that is needed to achieve a goal without unduly emphasising the outcome. It encourages reflecting on how to learn and improve as fast as possible in order to reach the highest possible standard. It emphasises self‐referencing when striving to develop and goals including mastering a craft. A skill of coaching and support teams is to know when to emphasise outcome within a mastery environment to maintain maximum motivation, effort and wellbeing.

Mastery's significance to wellbeing and performance of individuals and groups is often underrated. It is a key element of culture. Winning and losing can too easily detract from maintaining a mastery climate. Outcome cultures also have a use‐by date. Mastery climates emphasise sustainable targets that stand the test of time and stay relevant beyond winning and losing.

The New Zealand All Blacks

The culture of the New Zealand All Blacks rugby union team has been discussed a great deal. It is explored in detail in James Kerr's 2013 Legacy.19 A year later the University of Otago's Ken Hodge collaborated with former All Blacks Head Coach Graham Henry and Assistant Coach Wayne Smith on a journal article for The Sport Psychologist that gives an excellent overview of the development of the All Blacks culture from 2004 to 2011, culminating in a World Cup victory over France in 2011.20 The victory was on the back of New Zealand's worst ever World Cup performance in the previous tournament held in France in 2007, when for the first time they didn't reach the final four teams. The result created uproar in their rugby‐loving home country and was likely a contributor to an even greater emphasis on a team mindset and culture build that contributed to New Zealand securing back‐to‐back Rugby World Cups and lofting the trophy at the next opportunity in 2015.

In relation to motivational climate, Hodge, Henry and Smith signposted eight themes: (i) a critical turning point, (ii) flexible and evolving, (iii) dual management model, (iv) ‘Better people make better All Blacks’, (v) responsibility, (vi) leadership, (vii) expectation of excellence and (viii) team cohesion. They summarised their practical suggestions for coaches: ‘involve athletes in meaningful leadership roles via a version of the dual‐management model, adopt a mindset for transformational leadership via focus on individual consideration, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, fostering acceptance of group goals, high performance expectations and appropriate role‐modelling, learn how to be an emotionally intelligent coach by developing interpersonal and intrapersonal competencies of perceiving emotions in self and other and implement autonomy‐supportive coaching strategies’. The paper quotes Wayne Smith: ‘we worked on their strengths, rather than just their weaknesses. We wanted them to understand that they were there because of what they were good at.’

In the documentary Chasing Great, the then captain, Richie McCaw, explained that the team thought 2007 would be their moment, but they ignored the lessons from 2003.21 Richie, who went on to have one of the most decorated careers in rugby union history, said of the 2007 quarter‐final loss, ‘It didn't come down to talent. It came down to when the heat was on we weren't able to find a way to win. Training harder or being fitter wouldn't have helped. We had to admit we didn't have the tools in the box that we needed. We needed to not just pay lip service to the mental side. We addressed the elephant in the room and went to find the people and put time into the mental stuff.’

Of the 2011 World Cup victory, Richie said, ‘Instead of being scared I was embracing it, thinking bring it on.’ There's little doubt that the All Blacks had built an effective learning environment. ‘A key to whatever you do in life is to have a challenge and learn. If you stop learning, you can get sick of what you're doing. If you can get better, that's why you keep turning up.’ That mindset carried over to the 2015 World Cup, about which Richie said, ‘You want to be in that situation to test yourself. This is the 50‐foot wave I've been wanting.’

Building culture

There are many factors to consider when building a culture. It's one thing to hang a poster on a wall with some values printed on it, but to live a culture is altogether different. There are many ways organisations and people can do this. Here are a few thoughts from my experiences working with a wide variety of sports, schools and corporates on creating a culture.

TERMINOLOGY AND ENGAGEMENT

Commit to building a values‐driven culture. Engage and involve all stakeholders across the organisation in the importance of culture, and encourage them to contribute to culture build and reviews. Be clear on how you want to frame the culture: Is it more fun? More serious? More outcome or more process?

Start with the end in mind. Will it be framed in terms of mission, values and behaviours? Variations include: Purpose–Vision–Values–Behaviours and Purpose–Values–Behaviours. I've seen some organisations come up with phrases like ‘why we exist’ or ‘our manifesto’ or ‘our DNA’ to define or reflect a focus or an enduring component of their culture.

Once a structure is determined and the components propagated, be clear on how culture will be integrated and reviewed. Engage a range of stakeholders in order to maximise buy‐in, and emphasise culture at recruitment and in the course of induction. I recommend specific staff or consultants, such as performance psychologists, be nominated to facilitate this process.

I have asked sporting squads and groups engaged in a culture build questions like: ‘How is the group currently perceived?’, ‘How do we perceive competitors?’, ‘How would we like to be perceived?’, ‘What do we stand for?’, ‘How can we live the culture?’, ‘What behaviours are required?’, ‘What examples of positive behaviour do we have?’, ‘What are the benefits of working on culture?’ and ‘What gets in the way of our living culture?’

CLEAR VALUES AND BEHAVIOURS DESCRIBED

Many people are annoyed by vague values and behaviours that are difficult to relate to, too abstract, not relevant or not lived. Ensure that the culture includes clearly comprehensible terminology and values and behavioural definitions. The culture should stand the test of time and be relevant beyond one season. Specific team goals, such as a certain number of wins in a season, a ranking or a position, are goals that a culture may help the team achieve, but they are not a part of the culture. Goals are a part of a broader strategic plan that also includes culture.

SUPPORT PEOPLE AND PERFORMANCE

Support of both people and performance is essential in sport. Processes that enable athletes to maximise their capacity to perform, including access to resources, training and competition opportunities, should be available. Healthy cultures foster and compliment athlete determination and help them achieve their goals as well as be comfortable and grow as people. More on the people aspect in step 6 on wellbeing.

LEADERS LIVE, MODEL AND DRIVE CULTURE

While each person in an organisation influences its culture, and ultimately everyone is responsible for culture, its leaders have the greatest influence on how it is presented, lived and prioritised. Critical components are how much culture is valued and how it is built into processes. Coaches and leaders in particular can determine whether the culture shines and thrives or becomes murky and fades into the background.

COACHING, CELEBRATING AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Develop individual, small‐team and larger‐group education related to culture. Integrate reflection on culture into formal performance reviews as well as more informal conversations. Ideally, culture should be integrated into the organisation's narrative, its stories. Create opportunities to celebrate people and processes that exemplify and strengthen culture.

Culture can help ease the tensions experienced around performance conversations. Use culture to discuss behaviours that do or no not align with what is desired. Pointing out that a behaviour is not aligned with the culture doesn't reduce individual responsibility, but emphasises behaviour that is not aligned to culture.

DISPLAY AND SHARE

Ensure culture is reinforced internally and, when appropriate, externally. Determine as an organisation what is to be displayed, how and where. What exemplary stories will be shared? Will culture be reinforced on letterhead, in presentations, email signatures and websites? External stakeholders are far more interested in culture now than ever — they want to know what a sport stands for to ensure they are comfortable being aligned with it.

INTEGRATE INTO PROCESSES

At interviews, explain culture and assess cultural fit. Selected meetings can reflect on culture. Seasonal reviews and exit interviews are an opportunity to obtain feedback. At times a culture coordinator may facilitate cultural conversations. Careful consideration should be given to who will be formally charged with integrating and maintaining culture.

MONITORING AND EVOLVING CULTURE WITH DATA AND MEASUREMENT

Culture can be assessed quantitatively either by directly rating specific elements of the culture or by indirectly assessing related aspects like wellbeing, engagement, social‐emotional constructs and performance outcomes. There are many benefits to this kind of analysis, including recognising strengths and development areas, maintaining accountability, and balancing qualitative reflection or impressions about culture with real data. The data can be collected simply by creating a survey for people to rate and comment on, for example, how well they think values and behaviours are being upheld. In collecting data on culture, I have often used independent surveys that reflect culture, including engagement, as well as the specific rating of self and groups on the values and behaviours a sport adopts.

VALUES CONGRUENCY

As mentioned in step 4 on leadership, people whose values align with those of the organisation are often better able to contribute. They are usually more comfortable in the organisation. I often illustrate this with the example of the stress that would be experienced by a health advocate working for a tobacco company. Culture and individuals thrive when the values of team members, including staff and athletes, are congruent with the values of the organisation.

DIVERSITY

Hiring based on culture and values congruency doesn't mean everyone in the organisation should be the same. Effective cultures thrive on diversity, whether in gender, race, age, experience or thinking.

Challenges to culture

There are many challenges to building and living a culture. Here are a few elements that I consider when investigating the maximum impact a culture can have.

PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT, GEOGRAPHY OR SIZE

Leading and building culture can be simpler if everyone is in one place, just as a staff of 500 poses difficulties that a staff of 50 may not. And, as we've discussed, ensuring that values are relevant to athletes, as well as to coaches, support and administrative staff, can be a challenge.

Overestimating the impact of the physical environment, with its multiple meeting rooms, top‐shelf whiteboards and shiny signs, can cause us to forget for a moment that culture is created and reinforced by people and their behaviour. Mindset towards culture is the most important aspect. Physical structures reinforce culture but they do not create it. On the other hand, people do need a physical environment in which they are comfortable if they are to work productively and interact effectively.

CHANGE

Without ongoing commitment and maintenance, disruptions such as changes in leadership, organisation direction and staff can all dilute culture. New leaders often want to create their own mark on a team or organisation, including shifting culture. The foundation of a culture should remain reasonably constant, with recognition that at times some shift may need to occur for it to remain progressive and relevant.

At times, a lack of change can be as counterproductive as too much change. Effective organisations strive to retain competent staff who live the culture, and to part ways with staff who sabotage it deliberately or inadvertently. Many teams experience renewed energy when establishing a culture but find it difficult to sustain the commitment that keeps it alive, particularly considering the constant changes that often occur in sporting environments.

COMPETITIVE–COLLABORATIVE BALANCE

A genuine balance between competitiveness and collaboration is a key ingredient to sustaining a solid culture. As many high‐performance oriented individuals know, a healthy internal competitive environment can help drive high standards. Competition for selection or simply competitiveness at training can be extremely helpful and healthy. However, this becomes counterproductive when competitiveness overrides collaboration. Competition may be between athletes, coaches, support staff or administrators. The competition may be over results, a contract, for selection, attention or credit. Unhealthy competitiveness can drain people and culture and erode performance. Collaboration can keep competitiveness healthy.

INTENSITY–ENJOYMENT BALANCE

Something to keep in mind when building a sporting culture is that if it's too businesslike and formal it can stifle individuality and suffocate performance. The intensity involved in sport needs to be balanced with fun and enjoyment for culture to be sustained. Everyone needs a laugh at times. Sometimes fun happens inadvertently; at other times it's planned. A sporting culture is not based simply on a code of behaviour characterised by rules and curfews. Behaviour management is at times a relevant aspect of culture, but it's not the culture. Understanding how to balance intensity and enjoyment is a relevant aspect of culture in sport.

Building a good culture is hard; keeping a good culture is harder

Thinking about how difficult it is to build and sustain culture in sporting environments, Dave Andersen had some interesting observations on the NBA. ‘In my experience only about five teams in the NBA have an effective team culture. We place a much bigger emphasise on culture in sport in Australia than do other places I've played, including Europe and the USA,’ Dave told me. This may be one reason why the Australian men's basketball team were looked upon so fondly at the Tokyo Olympics. Like the swimming team, they exemplified a deliberate culture build that had started years before.

The men's basketball team achieved their best‐ever result with an inaugural Olympic bronze medal in a highly competitive environment. Patty Mills, who was team captain along with coach Brian Goorjian, placed great emphasis on culture. Immediately after the bronze medal victory, Mills spoke emotionally to Channel 7: ‘… it's our culture … Australian culture, our Aussie spirit … we have been able to build our Boomers culture by understanding the lay of the land that goes far beyond basketball … always giving back … understanding where we come from … living in the present, and who we represent.’ Mills’ speech was applauded globally and reflected just how much a positive culture adds to a team.

The culture was built on the foundation of a heartbreaking loss by just one point to Spain at the 2016 Rio Olympics. In Rio, the Boomers were leading by one point with under 10 seconds remaining, only to lose by one point. It was their fourth fourth place at an Olympic Games, which added to the meaning and importance of culture at Tokyo. Mills, who had played in that game in Rio, had additional fire. Dave Andersen, who played in 2016, was one of several Australian players not at Tokyo, which meant they ended their careers without an Olympic medal.

Of the Boomers’ culture, Dave Andersen said, ‘Definitely the culture footprint was planted as far back as 2008 at the Beijing Olympics, with Brett Brown coaching. Patty Mills was only 20 years old and playing his first Olympics. We had a goal to try to keep the nucleus of the team together and to carry it forward from then. We wanted to make and keep Australia competitive on the world stage. That created a camaraderie that was off the chain, and it was fun as well. So, the success in Tokyo started back then.’

Summary

Time, energy and resources are needed to build and sustain a positive, effective culture. Performance doesn't happen or exist in a vacuum. It is part of a dynamic psycho‐social system that affects people, how they operate, learn and maximise what they have trained. Its impact on people personally and on their performance cannot be overestimated. There are many ways to build and sustain effective environments and cultures, depending on the sport, the size of the group and how often they come together.

A key priority is to ensure leaders drive culture. Psychological safety and emotional intelligence in relationships and communication are vital ingredients. An emphasis on learning and mastery, as well as being aware of what helps build or challenge effective culture, are other ingredients that contribute to maximising culture.

In strong positive cultures everyone is on the same page and everyone is growing. That enables opportunity for people and performance to thrive.