STEP 2

BOOST YOUR RESILIENCE

Mat Hayman could be described as a journeyman in road cycling. His professional career in one of the most physically challenging sports lasted almost 20 years. He rode for high‐profile teams such as Rabobank, Team Sky and Orica–Green Edge and competed in the Tour de France four times. Mat also won gold in the road cycling at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games. Through most of his career he was typically a ‘domestique’: a support rider who rides tactically for the benefit of the team. He also became a one‐day race specialist. Mat experienced many ups and downs through his career. Along the way, he learned how to deal with these challenges, and the lessons learned had to be applied again and again.

Mat's career‐best achievement came when he least expected it. It was in his favourite one‐day classic, the gruelling Paris–Roubaix. In 2016, the 15th time he competed in the race, he crossed the line in first place by less than a second. The Paris–Roubaix is held over 250 kilometres of French countryside, with more than 50 kilometres of the race on old cobblestone farm tracks. In the insightful documentary All for One, which chronicles the formation and journey of the Australian cycling team, Orica Green‐Edge, as well as Mat's own personal story, legendary race commentator Phil Liggett described the Paris–Roubaix as ‘one that everybody hates to ride, but everybody wants to win’.1

Mat's mantra: Always keep riding

When I interviewed Mat about his career he reflected, ‘My first races at the Paris–Roubaix were far from successful. In 2008 I was stone last. My job was to support my teammates and I just wanted to help them and get to the finish line. It would have been easy to give up, but it would have hurt more, in the long run, to stop.’ He recalled how, after those early results, ‘my relationship with the race blossomed’. That relationship, with encouragement and support from an older Belgian teammate, Marc Wauters, who he looked up to, proved to have a lasting and telling impact. ‘Like me, he was not a traditional winner. He was a worker, an unsung hero, but instrumental to the team. He used to say to me, “always keep riding”.’ It became Mat's mantra.

After years of persistence, in 2016, and now an experienced elder statesman of the team, Mat had put together a solid pre‐season. In the intervening years he had had varying results, from 8th in 2012 to 76th in 2015. Then unfortunately — or fortunately, as it turned out — six weeks before the 2016 event, Mat crashed in a lead‐up race, fracturing the radial head of his elbow. The doctors told him his Paris–Roubaix was over and he returned to his family at their base in Belgium, arm in cast. ‘I was disappointed but looked at the silver lining of getting home and spending some time with my five‐year‐old son,’ he said. ‘I also thought, let's get on the wind trainer and see what I can do. So when I got home, I started doing sessions on the wind trainer in the garage. I had no real goal or certainty at the time.’

Five weeks later, cast removed, Mat met up with the team again and, in a last‐minute decision, secured the final position in the team selection. ‘From my unusual lead‐up I had no expectations.’ In the race, however, after about five and a half hours, with 15 or 20 kilometres to go, he was in a breakaway group of five. ‘I realised it could be my best performance. Then I over‐corrected on a corner and got dropped from the group. My first reaction was Why me? I had a total letdown and fell in a real slump. Why did I dare to get my hopes up? was another thought that came into my mind. Then, in a moment, I decided to change that thought to If I don't go now and do absolutely everything I can, I'll never forgive myself. I thought, left leg, right leg, keep going, and started chasing the group down.

‘When I caught the pack, I had the opposite feeling — it was an absolute morale booster. I had a new lease of life. I realised after that if I hadn't had that error and that moment, I might not have won. It impacted how I thought and behaved and the choice I made for the remainder of the race,’ he recalled with a smile. The final sprint to the finish line resulted in a narrow victory. It was followed by emotions of disbelief then elation. ‘I can't believe it,’ he said on finishing. ‘This is my favourite race. It's a race I dream of every year. This year I didn't even dare to dream!’

Mat's story highlights the roller‐coaster of emotions that can occur in the lead‐up to and during an event. It also reinforces the importance of a resilient mindset, manifested in this instance it was how he coped with the initial injury, how he trained back at his base in Belgium, how he dealt with almost not being selected, and then the race itself. His resilient mindset was built long before his victory. It was forged through his wide range of experiences, his passion for the event, support from his team, a willingness to keep having a go, and his self‐talk around that mantra: ‘always keep riding’.

Aim to be resilient

The only guarantee in sport is that there is no guarantee. All athletes experience losses, disappointments and setbacks. They are more common than observers will be aware of and are a part of any athlete's journey. Indeed, these experiences are part of life. How challenges are perceived, interpreted and managed is what resilience is about. For athletes, resilience is an essential ingredient of advancement, and becoming resilient should always be a goal. Consciously learning and working towards being more resilient should be embraced, because you can be sure it will be called upon.

I view resilience as being able to deal with adversity, to bounce back from challenges, big or small, and to keep going, regardless of the circumstances. Resilience is determined by how a person thinks as well as what they do in a wide variety of circumstances. They may not be able to do much to change a situation, but should nonetheless aim to remain steadfast and positive. Sometimes they may manage to manufacture no more than a hint of resolve, but they still take positive action. Resilience shapes how a person thinks and what they do. Some people will even seek challenges and thrive on them.

A person may need to be resilient in order to deal with thoughts or fears that others might view as insignificant. Worry, anxiety and fear can take over. Resilience is often required in these situations.

In my work I have learned to respect a person's experience from their viewpoint. One thing that working with people's mindsets teaches you is not to judge. The same circumstances will be experienced differently by different people. Many factors influence whether a person views an event as a challenge as well as how they cope. These may include whether or not they are prepared, their expectations, their experience in a particular environment or the importance of events in the context of the bigger picture. A person's self‐image and their emotional state at the time of an event can also influence how they interpret and manage a situation. Resilience is also built from creating opportunities for experiencing success, not only overcoming challenges.

Being clear on what resilience looks like in a range of circumstances can be powerful. It primes the mind. I invite athletes to reflect on when they have been resilient. What helped and how were they able to be resilient? I introduce activities and use worksheets to keep records of these resilient experiences and the strategies used. This shifts the focus from the challenge to the thoughts and actions that enabled forward momentum. It's amazing how resilience stories can be embedded in a person's narrative. It helps shift the enduring story from the challenge to the recovery or management of the situation.

For example, when working with athletes with two or more knee reconstructions, I look at the recovery as well as the injury. With a change of emphasis, the focus of the story can shift from the injury to the recovery. Many people have more resilience capacity than they realise. Sport certainly provides an opportunity to grow resilience.

Break it down into smaller parts

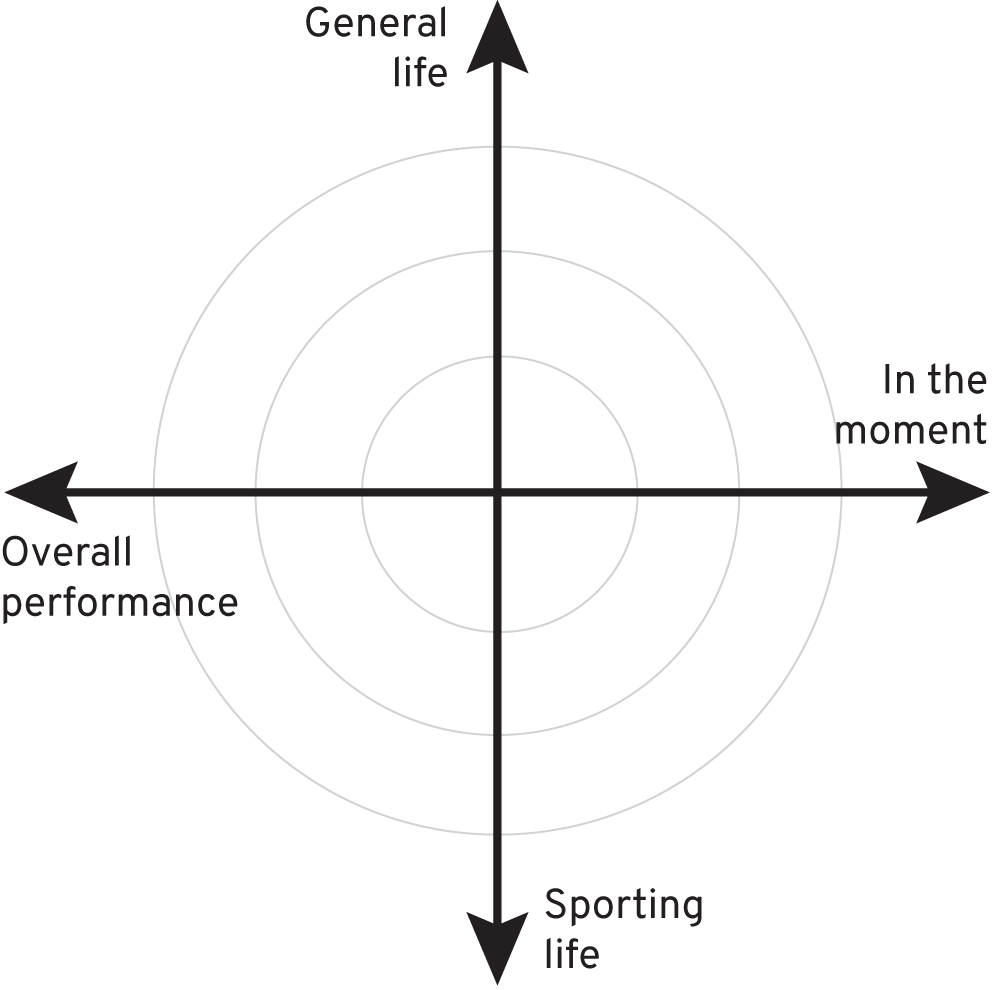

There's little doubt that resilience is important across a sporting journey just as it is across a lifespan. Challenges will always arise. How well prepared a person is, and how they respond to them, contributes to their experience in pursuing the goal and to the eventual outcome. Resilience is indispensable in a broad range of different circumstances, as may be seen in figure 2.1 (overleaf).

Different aspects to navigate within each component are outlined in table 2.1 (overleaf).

The explanatory list in table 2.1 is not exhaustive, and there are other details that could be included in each category. This model considers resilience ‘in the moment’ or during an event, compared with managing overall performance including before or after the event and week to week. It also considers life in general and sporting life.

I created this model to break resilience down into smaller components that athletes can more easily identify and manage. Of course, categories overlap, and how one is managed influences and impacts on others within the model. Helping athletes to focus on different categories if something is not going well means strategies and mindsets can be applied to deal with different, smaller situations. The model also helps people to recognise that resilience isn't fixed. It can vary from situation to situation and from time to time. It also helps people to recognise that if there is a challenge in one area, it doesn't mean everything is bad.

Figure 2.1: Resilience compass

This model of resilience is equally useful in sport or other real‐life experiences. The categories for sporting life, in the moment and overall performance can be interchanged with any other endeavour — at work or school or for any other task or project. Importantly, resilience can be taught and developed. There is no doubt that accumulated experience in dealing with challenges assists with this. The challenge with experience is that she teaches the lesson after the event, which, though inevitable, is not always desirable. What's important is that the experience is used for personal and performance progress.

Table 2.1: a resilience model

| In the moment | In front or behind during a competition Win or lose a contest Scores for or against Facing defeat or victory |

| Overall performance | Performance within a season or competition blocks General week‐to‐week training including, development of mindset, skill or conditioning Form slumps or winning streaks |

| General life | Relationships Family Living arrangements Study and work outside sport Finances |

| Sporting life | Contracts Development and progression Relationships with peers, competitors and coaches General demands including, travel and time Balance Sport politics Selection, injury, illness Media |

Ride the roller‐coaster with multiple resilience strategies

Seeing the roller‐coaster of experiences as part of sport can certainly help an athlete confront and manage challenges as they arise. Acknowledging that challenges exist and anticipating them can help athletes cope with them when they occur, as can acknowledging that when striving to achieve something, a wide range of challenges and emotions are inevitable. The more you strive for anything, the more likely it is that you'll come up against challenges. This doesn't mean you like the ups and downs, but you are more prepared for them. Applying this mindset to a challenge helps you embrace challenges with a management mindset of ‘make the most of this time’ by (a) recognising it as temporary (when that's the case), (b) recognising that lessons learned from a challenge can contribute to improvements and (c) looking forward to when circumstances are easier. Embracing the roller‐coaster as ultimately contributing to progress is another way to look at challenges.

One big challenge Brigitte Muir had to overcome to achieve her goal of climbing the seven summits was fundraising. As with many sports, climbing mountains is not a cheap pursuit. ‘As well as trying to get sponsors to fund my goal, I got jobs to raise money to climb mountains,’ she told me. ‘I did all sorts of work, including grape picking and painting.’ But raising money was far from her only challenge.

In 1993, when Brigitte made her first attempt on Everest, the weather was just too bad. ‘That's the nature of it,’ she commented pragmatically. On returning in 1995, she was with her then–husband Jon, who was a fit and healthy person but got sick on the mountain. ‘I had no choice. I had to get him back down.’ On a second attempt that year she got (perilously) closer. ‘I was at the back of a group on a steep section of the ascent. We got to just over 8500 metres (with less than 300 metres of climbing to the summit) and my headlight went out. It was dark. Pitch black. I couldn't see in front of me or behind. I made the big mistake of not saying anything straight away, so I was stuck. From experience I knew I had to wait and not try to go anywhere in the dark. I couldn't go up or down. I sat still and ended up waiting for three hours until I could see. By the time I had visibility it was too late to ascend and I was way too cold to go up anyway, so I made my own way back down to the last camp.’ The group summitted and for a long time had not even noticed she was missing.

‘After those experiences, I needed to work on my morale and reassure those supporting my quest. I decided I needed to climb an easier 8000 metre peak with no oxygen and no Sherpas or guides. It was necessary because I hadn't climbed above 8000 metres on a mountain yet.’ Achieving that goal gave her the injection of confidence she needed, and she returned to Everest again in 1996. It was a tragic year on the mountain. Over the season, 11 people died trying to reach the summit. Her trip became a rescue mission rather than a summit attempt, as planned.

Finally in 1997, determined to complete her task, she returned once again. It was still not without drama. During the ascent, the expedition leader became unwell at base camp. Tragically, he died in his sleep. On the mountain, the weather also wasn't looking good, but a window opened. ‘We left for our summit attempt at about 1 am. We stood on top of the world at 10.30 am.’ But on the way down she faced another challenge. ‘I got pulmonary oedema. It was so difficult to breathe I couldn't sleep. I had to stay awake for 65 hours to get down.’ There were challenges around every corner, including getting back down safely, but she finally achieved her goal.

Brigitte's story demonstrates her capacity to deal with expected and unexpected challenges in each of the areas described in the model in figure 2.1. The strategies she used included keeping her challenges in context, staying determined to achieve the goal, learning from past experience, using supports and being patient. Through her resilience, Brigitte not only climbed the seven summits, but achieved her supplementary goal of seeing the world on her way.

Metacognition relates to an awareness of and, ultimately, control over one's thinking. I sometimes refer to metacognition as thinking about how you are thinking, which is relevant because not everything you think is true. The research highlighted indicated that high performers reflect on how they think about and interpret a situation, which helps them to reframe and deal with challenges. Thinking about how and why you are thinking something can be very empowering. Metacognition also helps a person to know and understand themselves, including how they approach different situations and the strategies they can use. That's one reason why I get people to reflect on how and why they handled certain situations a particular way.

Resilience grows with an open mind

Garth Tander has an impressive record in V8 Supercars, but he experienced many ups and downs across his career. ‘The early part of my career wasn't straightforward,’ he told me.

In 1997, Garth finished the Australian Formula Ford Championship in first place overall. It was a solid performance but it had exhausted his budget. With no options to compete in any categories in 1998, he was uncertain of where or if an opportunity would arise. His best option was to take up a role as a junior mechanic with the team he drove for. ‘I had no budget and gave up being a race car driver. I thought I was done, with no money and no opportunity,’ he admitted. Then, when Steven Richards, who was driving for Gary Rogers Motorsport, unexpectedly left after three rounds to take up an opportunity as a test driver for Nissan in England, an opening emerged. Richards’ opportunity was Tander's good fortune, as he excitedly took a call from Gary Rogers offering him a drive.

‘I finished the 1997 season in August and had not been in a car since when I got the call in March. It was only an event‐by‐event offer until the end of the year. It felt like every opportunity was an audition and I tried way too hard,’ Garth said. ‘I made lots of mistakes but luckily the team stood by me and gave me another year. It was a one‐year contract and the stability helped me feel more comfortable, which enabled me to make better decisions in the car when racing. From there I got a three‐year deal, but it was shaky at the start.’ Bumps in the road weren't over yet.

After a good start to his new contract the team was struggling, and Tander's performances again began to drop away. ‘The sport had become more competitive and I had to keep up high performances. I started trying too hard again, overdrove and made way too many mistakes. I ended up taking a calculated risk and agreed with the team to finish my contract. I was 24 years old by then and realised I had to find a new team and a new mindset.

‘Early in my career I didn't know what resilience was and how it could benefit me. I tried too hard to impress instead of letting the process of gaining experience help me grow. When we were struggling as a team, I really needed to develop resilience.

‘For me, resilience is about looking in the mirror and saying I did everything I could and I helped the team do what they could to perform. In motorsport, it's not enough to say you did everything you could, without considering whether you assisted others. Resilience is not just about performance and technical execution. It's about doing your role as a cog in the wheel for the team. I learned that I needed to be open minded and look beyond the timesheet to determine if I was being resilient.’

As these stories illustrate, athletes who bring a resilient and learning mindset to challenges are better equipped to navigate the obstacles they confront on their sporting journey. With an open mindset, resilience grows over time.

A learning approach to building resilience

In 2016, a research study on resilience found that a combination of psychological characteristics, social support and learning factors assisted athletes to navigate their way through challenges.4 The project involved 20 athletes between age 20 and 29 competing internationally in sports such as athletics, archery, mountain bike riding and hockey. Challenges in the study related to sport‐specific experiences such as illness or injury, and not personal life trauma.

The researchers found that the challenges were negotiated through skills that were brought to, rather than generated by, such experiences. The research also concluded that, when effectively managed, events that require a resilient mindset can ultimately increase focus and motivation. The athletes used a range of strategies:

- Within the psychological characteristics, motivation was a key to stimulating and driving recovery. Increased focus on a specific goal and a reflective attribution style that attributed success to controllable factors and failure to uncontrollable factors was identified in the athletes. This attribution helped to maintain self‐esteem and motivation. (More on attribution style shortly.)

- In relation to social support, the athletes described the value of identifying and knowing when to utilise social supports.

- Learning factors that assisted the athletes included drawing on and applying learning from previous experiences and enabling a ‘big picture’ approach to their situation.

How athletes deal with challenges was also investigated in a study by experienced psychologist Dave Collins and colleagues titled ‘Super champions, champions and almosts: important commonalities on the rocky road’. This research, also referred to in the introduction, comprised interviews with 54 athletes from team and individual sports including soccer, rugby, athletics and rowing.5 ‘Super champions’ had accrued a minimum of 50 appearances for their national team while ‘champions’ represented their country but had fewer than five international caps. ‘Almosts’ had achieved at youth level but had played only at second‐level national league in their sport.

The researchers found that super champions were more proactive in dealing with challenges and differed from champions in how they conceptualised, thought about and actioned their experiences. They appeared to arrive at a challenge with an established attitude, rather than the reactive response adopted by the almosts. They also had a ‘learn from it’ approach to their challenges, while the lower achievers were characterised by external attributions and often seemed almost surprised by failure.

The authors noted that most of the challenges experienced were sport related, such as injury, non‐selection or deselection, rather than personal issues. Interestingly, they also theorised that the proactive strategies used by higher achievers might begin to develop in teenage years, even before they got started on the ‘rocky road’. They found no evidence to support a necessary role for major trauma in the development of resilience. The studies indicated that high performers use a variety of skills to enable them to be resilient. Learning from experience was a central theme.

In my experience, healthy sporting environments facilitate proactive coaching of resilience. Teenage years are not a time when these characteristics are necessarily developed naturally; rather, they are developed from deliberate or inadvertent lessons. Such skills should be part of an ongoing education for any athlete or young person right through their sporting career or life journey.

‘I wasn't born with resilience,’ remarked champion aerial skier Jacqui Cooper. ‘I was probably weak as an individual at 16 years old. I didn't back myself then. At 16 you don't really know anything about yourself. When Geoff Lipshut said, “I think you can be great”, I felt like there was a shining light. I couldn't see the dream that he could see, but that was what I hung onto. His belief in me. From there I learned to be adaptive and resilient. I have no doubt resilience can be learned. I didn't want to forget challenges and move on. I wanted to remember them so I could applaud myself when I improved. I wanted to take this learning and put it in my resilience bank so I could use it to handle future challenges. I learned to take my failures with me, to try to avoid making the same mistakes. It was from my failures that I learned the most. A podium is great, but it only lasts three minutes, and I didn't learn as much. By the end of my career I was so robust nothing could throw me off!’

As mentioned, athletes face constant challenges — from niggling injuries to managing different relationships in a sport to fears and experiences of underperformance, even at a training session. Each of these experiences brings learning opportunities and are times to be resilient. Accepting these experiences as part of a sporting journey and viewing them as lessons and growth opportunities helps prepare athletes for dealing with them — not if they occur, but when they occur. That's what Jacqui did and it helped her performance and to prolong her career.

Keep going: injuries, disappointments and setbacks

By the time of the 2002 Salt Lake Winter Olympics, Jacqui had become a three‐time world champion and earned the right to be the gold medal favourite leading into the aerial event. She had practised her sport for 13 years and in that time she had finished 16th at her debut Olympics in 1994. In 1998 she had crashed out of the event. Now, as world number one, it was her turn to shine. Her resilience had grown, but it was about to be tested. One day before the Games a training accident shattered her knee. She had a tibia plateau fracture, ruptured her ACL, damaged cartilage and destroyed her knee capsule. ‘Since I was 16, I had never missed an event, so it was surreal to be sitting in the stands watching the event that people thought I was going to win. Four knee operations in the following 12 months rendered her unable to ski for two and a half years.

‘Everyone was feeling for me,’ she said. ‘After the injury, Geoff came to talk to me and said, “No one will blame you for leaving the sport. But if you do want to come back, you'll need to come back different, to reinvent yourself. You'll need to relearn everything and come back even better.” I realised I needed to move on from being an “acrobatic moron” and risk‐taker to being a technician.’ It took four years, but by 2006 she was back to world number one. ‘That conversation with Geoff invigorated me. I set about reinventing my skiing.’ Before returning to Australia, she stayed on at Salt Lake as long as she could, watching the semifinals. Waking up after surgery back in Australia, she saw that her younger teammate Alisa Camplin had gone on to win the gold. She had never won a major event before. ‘I was so happy. I was happy Australia won a gold and it took a lot of pressure off the sport after all the support we'd been given.’ Gratitude was Jacqui's overriding emotion going into her journey of rehabilitation and recovery. Her resilience had grown to a level where she was able to think beyond her own challenges to appreciate the achievements of others.

In 1999, at the age of 18, basketballer Dave Andersen left Australia for his first professional contract in Europe with the Italian squad, Team Bologna. It took him only a few years to become entrenched as one of the best imports in Europe. By 2004 he had been a central figure in winning two championships, as well as claiming a most valuable player in the finals series. He was quickly sought by CSKA, Moscow, in their bid for a title in the EuroLeague, a competition held each year between the best teams in Europe. After Dave's arrival at CSKA, the team proceeded to win four straight championships. The NBA was also beckoning. That would fulfil a career dream. Then, in 2007, at a big match in Spain against FC Barcelona, a freak accident left him with a snapped tibia and fibula near the ankle. His tendons and ligaments were also badly damaged.

‘It was Australia Day too,’ he recalled. ‘People said it was a career‐ending injury. I flew back to Moscow with it untreated, and my leg blew up like a balloon. It was a pretty painful flight. Once there, I took on board my treatment options and decided to have surgery back in Australia, which meant flying back home with the breaks. I had a great medical team in Melbourne who I had confidence in, so their advice helped me cope. I knew that resilience had to be a big focus for me then.

‘I think resilience is the most important mindset for an athlete or anyone,’ Dave told me. ‘It extends beyond injuries. You need to keep working hard even when you don't feel like it. To stay resilient in general I also learnt to adjust my goals, which kept me looking forward. I carry a resilience card in my wallet — it's still there, even though I've retired!’ It took about 10 months of rehab to recover, but after working with his support team and being clear and determined to pursue the NBA dream, Dave returned to Europe in 2008, this time playing for FC Barcelona, a European sporting powerhouse and, ironically, the team he was playing against when he was injured. From there the call finally came. It was from the Houston Rockets in the NBA. All his perseverance and resilience had paid off. He was US bound.

Jacqui's and Dave's stories are just two examples of what many athletes experience on their sporting journey. In each case, their motivation, focus on longer‐term goals, use of supports and a mindset that saw their setbacks as growth opportunities enabled them to pick themselves up and get going again. While the specific instances described relate to injuries, they are only examples of the approach to dealing with any challenge.

Other than injury, disappointments can take many forms. Not having a personal best (PB) for an extended period of time is one. Non‐selection in a squad or team is another. Not attaining a level of desired performance or achieving a desired outcome are also experiences that many athletes discuss as challenging and at times bitterly disappointing. Each of these scenarios requires a resilient mindset. Learning, staying patient, identifying positives and staying determined are only some strategies to manage these situations. Understanding the context of the performance is another, including how an opponent performed on the day.

Some might view Sasa Ognenovski's soccer journey as defined by disappointment after disappointment. He sees it differently. ‘Because I didn't have a traditional pathway, I saw my path as one of keeping going and never giving in to rejection. I told myself to keep believing in what I could do. I saw all of the experiences I had as opening my mind to what I needed to do. That developed my resilience to the point where I wasn't scared to try anything.

‘When I was playing in the National Soccer League (the local league in Australia) I paid for my own airfares and accommodation to go and trial with teams in Turkey, Croatia, Belgium and China. I didn't get selected by any of them. Then I got a call to trial for a Greek team and I paid for my fare to get back to Europe for that trial. I had 250 euros in my pocket and the public transport of a train, bus and taxi to get to the mountain training base cost me 248 euros. It ended up being worth it. It felt like a breakthrough when I was finally offered a four‐year contract. I started the first season well, but unfortunately the club went bankrupt and I didn't get a cent. I came home broke. The timing meant the signing cut‐off date for rosters in Australia had passed, so I went back on the tools as a carpenter and played in a local lower division.’

Through perseverance his agent got him a trial with the Brisbane Roar in the A‐league. ‘When I started training there I had a siege mentality, thinking I'm here now and I will do everything I can.’ He got a two‐year contract. Now 29 years old, he had three children and the family moved to Brisbane. ‘That's when I felt like I'd made it,’ he said. From there, his decade‐long journey of persistence began to reap rewards. From Brisbane, Sasa was contracted to Adelaide, then a team in South Korea, where he became captain and won man of the match in the Champions League, as well as Asian player of the year. It was then that he caught the attention of the Australian national team selectors and got the invite to play his first game for Australia against Egypt in Cairo, aged 31. ‘I felt vindicated,’ he recalled. ‘To be in the top 11 players in my country was an honour. It felt like all the work and training and all the trips around the world meant something more.’

Sasa's view of each disappointment as a learning opportunity helped him to grow, as did his willingness to spend all the money he had to get to trials. His readiness to travel around the world, even with his young family, also demonstrated his determination. His career was built on the back of a determined and resilient mindset. Sasa summed it up like this: ‘Without being challenged, you can't be elite at anything.’

Learning to lose

Learning to lose is an important skill that helps build resilience. No one enjoys losing, but everyone loses at some stage. Effective management of losing helps people to grow, keep going and work towards their goals. At times the losses can be ongoing. In reality, every win takes an athlete or team one step closer to a loss and every loss takes them one step closer to a win. In some sports, winning doesn't happen very often. Embracing the journey and the positive experiences beyond outcome is vital. Adjusting goals is also important.

A missed goal, a poor start, feeling unwell or sore, a lost contest, missing a final, podium or point against an opponent — all these situations demand that the athlete get up and get going again. Quickly. How well the athlete responds to such setbacks can influence the outcome of a performance. How they use the time between these moments to get going again is crucial. A sporting performance can be defined by a moment. It can be a fine line between winning and losing.

Rafael Nadal's performance at the Roland Garros French Open is one of the most commanding international sporting performances by an individual over the past century. On the clay court surface, he has won a record 13 tournaments in 15 attempts since his first victory in 2005. It's a staggering record. To win a Grand Slam tournament means winning seven matches from a draw of 128 of the best tennis players in the world. By the end of the fortnight, when the champion is crowned, 127 male and 127 female players will have experienced a loss. Only one female and one male player won't have tasted match defeat.

Along the way, even the tournament winners will have endured many mini‐challenges and defeats — in points, games and sets. How they respond to each mini‐defeat influences the next point, the next game and the next set. Ultimately, how the roller‐coaster ride of winning and losing is managed can decide the match and tournament outcome.

A review of every point in Nadal's 91 matches won in his tournament victories at the French Open up to and including 2020 indicates he has played a total of 16 234 points. Of those, he has won 9407 points and lost 6827. In percentage terms, it can be expressed as 58 per cent of points won against 42 per cent lost. It's unlikely that you would associate these figures with one of the world's most dominant sporting performances. Nonetheless it illustrates that even Nadal cannot afford to drop his head after losing a point. Indeed, resilience from point to point is surely one of his greatest skills. Yes, it also matters which key points are won, but resilience on points lost contributes to enabling a certain mindset on the ‘big’ points. This was never more evident than in his epic five set come‐from‐behind 2022 Australian Open win, where he lost 189 points in the match and won 182.

Resilience, as noted, can be taught. Both mindset coaching and physical training can help teach repeat efforts, repeat surges and recovery from a lapse or mini‐loss. It is something Nadal has learned. One year in Brisbane, in the lead‐up to the Brisbane International tournament, I gave a lecture along with Toni Nadal, Rafa's uncle and long‐term coach. In his presentation he recounted how he coached Rafa even as a junior to go again, keep hitting through every ball, regardless of the outcome of the shot before. He taught Rafa not to worry about errors. In Rafa: My Story, Nadal describes his mantra: ‘Every single moment counts … what I battle hardest to do in a tennis match is to quiet the voices in my head, to shut everything out of my mind but the contest itself and concentrate every atom of my being on the point I am playing. If I made a mistake on a previous point, forget it; should a thought of victory suggest itself, crush it.’ It's not surprising he also outlines that ‘The key to this game resides in the mind, and if the mind is clear and strong, you can overcome any obstacle, including pain. Mind can triumph over matter.’ Regarding his uncle he says, ‘Tony conditioned me from childhood that every match is going to be an uphill battle.’6 From his commentary it is evident why Nadal treats the error, or shot before, once past, as simply a learning opportunity — it is just as he was taught as a junior. The coach of a world champion had instilled a learning approach. It's not surprising that Nadal has achieved what he has.

Life challenges

As much as we might try to protect people from significant life challenges, no one, not even elite athletes, can be isolated from the realities of life. During every sporting career, ordinary life still happens. Athletes, like anyone else, experience a full range of life events, including the difficult and even the tragic, such as terminal illness or sudden death of a family member, a car accident or another confronting event. Dealing with personal challenges, such as addiction or poor decision making, requires resilience. At times these experiences will stall a sporting career. For athletes in the media spotlight, sometimes these problems are publicly known; at other times they aren't.

In 1998, tennis player Scott Draper was in Paris, competing at the French Open. ‘I was with my wife Kellie, who had cystic fibrosis,’ he related when I interviewed him. ‘The night before my first‐round match she was in a lot of pain with what turned out to be a twisted bowel. We had to get to a hospital. It was midnight before we saw a doctor and she went in for emergency surgery and didn't wake until about 7.30 am. Thankfully she was okay, but I hadn't slept at all. I had to decide whether to play my match, scheduled for 11 am. Kellie had a great attitude and wanted me to play. “Muddy” Waters helped me make my mind up to play, and Mark Woodforde was kind enough to go to the hospital and sit with Kellie. So I went back to the hotel to get my gear and eventually arrived at the court at 11.05. I almost got forfeited. No warm‐up. Tony Roach was courtside and gestured to ask what was going on.

I was a carer as well as a professional athlete, so I already had perspective, but that added another layer,’ Scott said. ‘Because of Kellie's positive attitude, my motivation was sky‐high to win for her. It was a match I didn't want to lose. I ended up winning in straight sets. I rushed back to the hospital straight after to tell her the result. But it caught up with me later and I lost the second‐round match. It meant I dropped out of the top 100 for the first time in three years. From that experience and what Kellie was going through. I was able to look at the bigger picture.

‘At times I used to struggle with motivation because I was tired from dealing with bigger things than sport. I had a reputation for being inconsistent. I used to focus on doing what I could, in my circumstances, and that's what I judged myself on.

‘I used to think about my high percentage play and commit to that. Assessing myself on that plan, rather than on the result, helped me stay resilient. Investing 100 per cent irrespective of the outcome gave me peace. That was different from when I was growing up and used to make excuses and didn't take ownership.

‘Knowing my why helped me build my resilience and bounce back repeatedly. It helped me move forward. I haven't been a look‐back person, unless it was to learn from something specific.’

Scott's story illustrates how life challenges can and sometimes do impact a sporting career. In these circumstances, it may be necessary to adjust how an athlete is operating as well as how they assess themselves. They don't have to be resilient all the time. It's okay and normal to dip and experience a range of emotions, and to be upset, disappointed or to struggle in certain contexts. Recognising that every journey is unique and includes a wide range of emotions can help resilience.

Explanatory style

In the Collins study mentioned earlier in the chapter, reflective attribution style was referred to as a strategy athletes use to build resilience. Let's delve a bit deeper into that strategy.

Attribution style, also referred to as explanatory style, relates to the way people explain events to themselves. Typically, explanatory style is broken into three components: internal–external, stable–unstable and global–specific.

An internal–external style relates to whether a person attributes an event to their own actions or to external factors. Stable–unstable relates to whether a person thinks the event is a one‐off or will likely be sustained. Global–specific relates to whether the event is seen as impacting all aspects of their life, or just part of it.

How a person explains events reflects and impacts resilience. A positive or negative explanatory style has been associated with being optimistic or pessimistic. Importantly, explanatory style can be taught and learned.

The American psychologist Martin Seligman, often cited as the founder of the positive psychology movement, has been heavily involved in the development of this thinking, though the concept of positive psychology can be detected in many disciplines over centuries. In essence, positive psychology incorporates maximising subjective wellbeing for individuals and groups.

In one famous early study in 1968, Seligman and colleagues conducted a study using dogs.7 Under experimental conditions, the dogs became helpless and passive. With retraining, however, the dogs learned to become proactive and put in effort to overcome challenges in which they had previously been passive. The study gave rise to the expression learned helplessness, which led to the phrase learned optimism. In his popular 1991 book of the same name, Seligman outlined his thinking on the importance of optimism and discusses how explanatory style can affect pessimism and optimism in the face of different events.8

Optimism helps resilience

In 1990, Seligman applied his theory in a competitive swimming environment. He wanted to know how swimmers would deal with a challenging event that he created in collaboration with coaches at the University of California at Berkeley. In one part of the study, 33 high‐performance athletes including national and world record holders were asked by their coach to do a time trial for their best event.9

The coaches were instructed to provide false (slow) times to the swimmers after their effort, with the intention of producing disappointment. The coaches then gave the swimmers 30 minutes’ rest before repeating their effort. Seligman found that, in general, athletes with an optimistic explanatory style did at least as well in their repeat effort. The performances of swimmers identified as having a pessimistic style after simulated defeat, however, deteriorated. Swimmers with a pessimistic explanatory style were also more likely to go on to perform below expectations during the season.

Seligman concluded that ‘explanatory style predicted swimming performance. Optimists performed better than expected and pessimists worse than expected, particularly after defeat.’ It was also suggested that ‘explanatory style predicted swimming performance beyond talent’.

This study has a range of implications for coaching athletes on mindset skills, including coaching positivity and optimism. It's particularly relevant for dealing with defeat, disappointments or perceived setbacks. How an athlete explains the event to themselves affects their resilience. The optimistic swimmers who went faster may have thought: ‘it's a one‐off’, ‘the time may be wrong’, ‘I need to lengthen my stroke’ or ‘I'm better than that — I'll go faster next time’. The pessimistic swimmers may have thought: ‘it's not my day — I'm tired’, ‘I struggle under time‐trial conditions’ or ‘it's not fair to get only 30 minutes’ recovery’.

Fast forward to 2002, when a paper by sport psychologists Robert Schinke and Wendy Jerome provided an overview of three general optimism skills that can be taught as part of a broader, comprehensive resilience program.10 They recognised that with specific mindset training, performance can be improved in challenging settings through targeted cognitive or thinking skills. They discussed ‘evaluating personal assumptions’ (along the lines of explanatory style), ‘disputing negative thoughts’ and ‘de‐catastrophising’ as three key skills to be taught to enhance resilience in athletes. They noted that the interventions are also appropriate for staff, including coaches and administrators, particularly given that athletes’ resilience becomes more robust when they are placed in ‘resilience‐producing environments’.

These studies emphasise the importance of how events are interpreted. Indeed, in a number of the sports I have been engaged with I have given groups the opportunity to choose a range of topics under a ‘performance mindset’ banner to reflect on and build skill in, and optimism has been a frequently chosen topic. How events are debriefed, interpreted and explained is part of the education process. At times I also co‐present with athletes from the group to share how they remain resilient, positive and optimistic. Their stories become powerful not only for increasing connection and cohesion within the group, but also as a natural and specific learning experience. Importantly, when discussing resilience in these circumstances, specific examples that relate to the athlete and sport are of most benefit. I'm not referring to deeper personal factors here. Shared sporting experiences normalise challenges, provide specific strategies and increase potential avenues of support within the group.

Reflecting, reviewing, debriefing and feedback

Managing self‐talk and deciding who to listen to and who to ignore are also relevant strategies when looking to build resilience. With the emergence in social media of public commentary on athletic performances, this inescapable external noise can be a real challenge for most athletes. So a key skill for athletes is to take control, managing their own thoughts and filtering out irrelevant external information, to deal more effectively with situations and remain resilient.

Perspective needs to be layered into reviews and evaluations. As noted, very few athletes win consistently. Athletes not at the top of the mountain in their sport, including those regularly on the fringe of selection, or on the fringe of qualifying for a national competition or event, make up the bulk of aspiring and performing sportspeople.

Debriefing and reviewing at an appropriate time after an event is underrated as a strategy for learning and building resilience. Many athletes appreciate an effective review. Reflecting on an event enables them to process their thoughts and emotions. Debriefing need not be reserved for major events. Ideally it is incorporated into regular practice. Viewing the situation from a rational rather than emotional mindset helps. Understanding why something happened can help. These strategies assist athletes let go and move forward. Reviewing and debriefing can embrace emotions as well as facts. These processes can keep an event in context or perspective. Athletes are vulnerable to holding on to a negative interpretation of an event for too long. Having said this, at times simply moving on from a performance is necessary. Over‐reviewing can be draining. This reflects the art of coaching and performing.

Working with individual athletes or squads, I often ask them to review and reflect on events and experiences. Building these processes into post‐training and performance routines, as well as into annual or other cycles, should become habit. There are many ways to do this. One exercise I use is to ask athletes for their reflections under three categories: self, others and environment or circumstances.

Some people tend to overly attribute poor or disappointing performances to themselves. It is good to take responsibility for poor performances, but not when the performance is not necessarily very bad or can be attributed to other factors. Broadening the review under these three banners allows a more accurate picture of a performance to be drawn. Resilient athletes do not evaluate themselves purely and simply on winning or losing. They do not judge or explain their performances as simply good or bad — or, more extremely, as ‘great’ or ‘terrible’. Appreciating that performances can fall short at times shifts how a review is conducted, and a plan to re‐energise can then be developed. Avoiding extreme, emotive terms in reviews nurtures consistency and can sustain both physical and mental energy. There is a lot of space between great and terrible. Remember the adage, ‘You're rarely going as well or as badly as you think you are.’

Some athletes may at times struggle to accept responsibility for their performance or situation. They blame others or circumstances — the weather, a coach, an opponent or anything to avoid taking personal responsibility. This self‐protection mechanism can hamper progress. Honesty can be difficult, because if the athlete made a big effort but their performance was poor, it can be confronting to consider what this says about their capacity. Taking responsibility is the beginning of a learning process. Being honest, and knowing when to take and accept responsibility, leads to growth, and this requires resilience. Athletes have to be comfortable with putting their hand up and saying ‘my bad’, ‘my mistake’, ‘my responsibility’. Understanding when and when not to do this is part of a performance mindset.

I often encourage athletes to conduct their own review of their performance, preferably before their coach's. This strengthens responsibility, enables them to be more open to feedback and facilitates more meaningful conversations with the coach. Reviewing helps them confront small or large challenges as well as small success within a win or loss and stimulates growth. This doesn't mean the reviewing style should be confronting. The style can be supportive which, can help confront the performance. A simple strategy to manage this is to review what has been done well and what has been learned. It should also identify what is required to move forward physically, mentally, technically or tactically. For many athletes I work with, I often mandate reviewing what has been done well and what has been learned, regardless of outcome.

Recording these thoughts facilitates the debrief strategy. Reflecting on the information collected provides another learning opportunity. Patterns in performance are more easily detected in a structured review. This exercise, as noted, remains constant for wins or losses. As well as reviewing specific events, reviews of blocks of training and performances in the lead‐up to major competitions, events or finals series can narrow the focus and enhance motivation. Such reviews can be summarised as ‘major learning’, ‘what I'm proud of’ or ‘why I can do well’. In effect, the purpose of these reviews is to emphasise key actions to move forward.

To summarise, the following are questions I have used at different times in athlete debriefs and reviews to facilitate learning and resilience:

- What are the details including score, conditions, opponents?

- What happened overall?

- What did you do well?

- What did you learn?

- Did you execute your plan, or how did your plan go?

- How was your mindset?

- What are you proud of?

- How have you/we grown?

- Based on this experience, what do you need to do, or what action needs to be taken at training, as well as in your next performance?

Of course, I'm not suggesting all of the above are necessary in a review. They are simply examples to reflect on. I recall asking athletes to identify what they could have done better and what they have learned from strong winning performances, not just losses. When wrapped in a package that embraces growth, accepting and confronting performances and emotions becomes easier. High‐performing athletes don't want their reviews sugar coated. But they are less likely to become deflated or despondent after honest evaluations based on facts and embracing lessons to move forward. This can be empowering and foster resilience.

Team resilience

Team resilience is important. How well equipped individuals are to handle adversity, and how well the group is educated to support one another, impacts team resilience. This can be taught as a specific concept and incorporated into team performance planning and reviews, so team members are aware of their impact on the resilience of other individuals and of the collective.

These researchers identified four main resilience characteristics of elite sport teams: group structure, mastery approaches, social capital and collective efficacy.

- Group structure includes topics such as group values and norms, shared leadership roles, communication channels and group accountability.

- Mastery approaches involve learning processes and effective behavioural responses, such as not dwelling too much on setbacks and managing change.

- Social capital is about group identity, perceived social support and prosocial interactions, such as a no‐blame culture and frequent positive interactions.

- Collective efficacy includes drawing on past mastery experiences, group cohesion including qualities such as fighting spirit and commitment, and social persuasion that relates to feedback.

All four areas are important for team resilience. A no‐blame attitude and shared responsibility can lead to more efficient and effective problem solving and growth.

There are many challenges to team resilience, including external influences such as pressure from media, administrators and supporters. A demand for immediate results increases pressure in sporting environments. In these instances, team resilience and unity is vital. When unmanaged, pressure can lead people to become protective of their own turf and can fracture teams and negatively impact performance. Pressure is a time to increase resilience and unity.

At these times, communication becomes an important component of helping resilience. If athletes know and understand what is happening, they feel empowered. When there is a lack of information or communication, people can feel vulnerable.

Increasing communication within a group can help resilience, in and out of competition. If one person is struggling with performance, other team members can support them through instruction or encouragement, enabling them to hold their ground and helping the team to remain strong.

Navigating transition and other vulnerable times

As noted in the introduction, transition is a particularly vulnerable time for many athletes. It often brings new or unexpected challenges. Advancing from junior to open categories, returning from injury, a change in coach, changes of technique and physical changes are all times of transition. Moving to a new city or country, changes in relationships and changes in personal life circumstances can all impact coping.

How transition is navigated becomes important. Patience and an eye on the bigger picture also helps, as does staying positive. All contribute to a resilient mindset. When 16‐year‐old Storm Sanders moved from Perth to Melbourne, she didn't have as easy a path as she might have wished. However, she embraced these strategies to work through a challenging phase.

After the move, she quickly got down to work. Being at the National Tennis Centre and home of the Australian Open was inspiring, but it wasn't a fairytale transition. ‘I had challenge after challenge,’ she remembers. ‘It was not an easy road. I had injuries, setbacks and poor performances. From 19 to 23 I didn't get a full season on tour and felt like I was starting over multiple times. In 2018 I got a shoulder injury that wasn't able to be diagnosed for about four months. I couldn't lift my arm above my shoulder and didn't hit a ball for seven months. For a while there was no timeline and no certainty of recovery. I thought about giving up being a player and taking up coaching. But I decided to look for a positive. Resilience is finding a positive, even in adversity.

‘I wanted to find a way to get better at something, even if it wasn't tennis. I studied for a Bachelor of Science in Psychology. I also started doing match analyses of players on tour. It enabled me to see the game from a different perspective. I began to thrive in that tough and challenging situation. It also affirmed what I wanted to do — to get back to playing tennis. It definitely helped me when I started playing again.’

Unable to train, or restricted to minimal training, Storm was determined to stay positive. She used the experience to sustain her motivation going forward. Without knowing it at the time, she was also able to use the experience to her advantage in competition down the track. The more challenges she navigated successfully, the more resilient she became.

Adaptive perfectionism and flexibility

Striving for constant perfection can lead to burnout, dissatisfaction and misinterpretation of challenges. This may sound counterintuitive, given that the highest‐performing athletes must be relentless in their efforts to achieve the greatest success. But research with elite athletes has identified adaptive perfectionism as an important quality common to those who succeed at the highest level. That doesn't mean taking it easy. It does mean some flexibility to help resilience. I often use the analogy that if a rigid piece of wood is bent it snaps. Bend a piece of wood with some flex, however, and it will return to its original shape after being tested. Make no mistake, resilience is about flexibility and adaptability. This takes people beyond black and white, good or bad thinking.

In 2002, Daniel Gould and colleagues undertook a very interesting study with a group of athletes that provided revealing insights into performance.12 The study involved in‐depth interviews with 10 Olympic champions from both Winter and Summer Olympics between 1976 and 1998, who between them had won a total of 32 Olympic medals including 28 gold. They were, in other words, the best of the best. The paper identified 10 common psychological characteristics within the group. (This is discussed further in step 7 on performance.) One of the 10 characteristics was adaptive perfectionism.

The authors found that adaptive perfectionism was positively associated with achievement. Furthermore, the athletes in the sample were moderately high or high on personal standards and being organised but, interestingly, low on concern for mistakes. This indicates not that they weren't concerned with errors and challenges, but that they could contextualise them.

The athletes also reported that adversity, such as losing or frustration at training, was interpreted as teaching skills and attitudes important to psychological development. The authors noted that adversity contributed to teaching ‘how to lose with grace, mental strength, [and] determination as well as understanding that frustration comes with success’. Adaptive perfectionism helped resilience.

In 2018, a review of perfectionistic studies in sport was conducted by Hill, Mallinson‐Howard and Jowett.13 In their paper they distinguished between ‘perfectionistic striving' and ‘perfectionistic concerns’:

- Perfectionistic striving had a positive impact on performance, motivation and wellbeing.

- Perfectionistic concerns was related to maladaptive motivation and wellbeing, rather than to enhancing performance.

These findings reinforce the importance to ‘strive high’, without becoming overly self‐critical. When these two factors sit in balance, resilience can be maintained more effectively. Irrational self‐criticism along the lines of perfectionistic concerns makes resilience difficult to maintain.

Some athletes believe being perfectionistic helps them because it leads to obsessiveness and improvement. The studies mentioned, however, suggest that, taken too far, it can be counterproductive. Being too rigid and unforgiving of oneself can limit resilience. Resilience is not just about dealing with challenges and pushing on. It is also about knowing when to be flexible and forgiving. This approach helps athletes confront their fears and new uncharted territory that is a constant in their journey. Resilience is about finding a balance between when to push and strive and when to slow down, reflect and adjust. It helps to aim and push higher.

Summary

Resilience is about dealing with challenges, bouncing back and keeping going. It encompasses how a person thinks and what they do. It is a skill that can be developed through experience but also through specific strategies.

All athletes experience ups and downs and challenges, big or small, in sporting events or in life. Appreciating that many challenges including injuries, disappointments and setbacks are a part of sport is helpful and necessary. Athletes who see themselves as adventurers, always looking to scale new heights and embrace challenges, are often more resilient.

Focusing on learning, using supports, and remembering motives and goals can help build and sustain resilience. Debriefing — reviewing performances and events — can influence resilience. Learning how to manage explanatory style, being optimistic and balancing perfectionistic tendencies can help athletes remain resilient.