chapter at a glance

Organizations use strategy, technology, and design options to respond to opportunities and challenges in their competitive landscapes. Here's what to look for in Chapter 17. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHY ARE STRATEGY AND ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING IMPORTANT?

Strategy

Organizational Learning

Linking Strategy and Organizational Learning

HOW DOES STRATEGY INFLUENCE ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN?

Organizational Design and Strategic Decisions

Organizational Design and Co-Evolution

Organizational Design and Growth

HOW DOES TECHNOLOGY INFLUENCE ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN?

Operations Technology and Organizational Design

Adhocracy as a Design Option for Innovation and Learning

Information Technology

HOW DOES THE ENVIRONMENT INFLUENCE ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN?

Environmental Complexity

Organizational Networks and Alliances

Costco pursues a low-cost strategy in order to effectively compete. According to its CEO Jim Sinegal, "Costco is able to offer lower prices and better values by eliminating virtually all the frills and costs historically associated with conventional wholesalers and retailers, including salespeople, fancy buildings, delivery, billing and accounts receivable. We run a tight operation with extremely low overhead which enables us to pass on dramatic savings to our members."

Costco is the fifth largest retailer in the United States with some 53 million card holders and some 250,000 employees. With global sales approaching 75 billion dollars it currently ranks 29th on the Fortune global 500 list. Its goals are also as clear as its strategy—make money for shareholders.

"Costco is able to offer lower prices ... by eliminating virtually all the frills and costs historically associated with conventional wholesalers and retailers."

On the surface this sounds much like most large box discount retailers. So what is the difference?

Costco does not skimp on employees. From the start they have paid almost all full-time employees full benefits, including health care and retirement. And the base wages are among the highest in the industry. They also promote from within. It is not at all unusual to find that a store manager started her career with Costco.

Costco stores have a more limited range of items to cut carrying costs. Most stores have some five thousand items compared to about 100,000 for Wal-Mart. Costco also tends to carry more higher end products in their TV, automotive supply, and apparel departments compared to competitors. They often bring in very high quality brands with very low margins to stimulate store excitement.

There is emphasis on building in the long term. CEO Sinegal recognizes that Costco could bump short term profits by increasing markups and eliminating employee benefits, but that would be inconsistent with building a long term business. Further, it would not be consistent with the nurturing and development of customer loyalty.

how to compete in a changing landscape

The world in which organizations now operate provides countless demands and constraints, as well as alternatives and choices for survival and growth. This world is also constantly changing, and doing so in fundamental ways. To be successful, organizations need, at a minimum, a sound strategy and the ability to learn.

We indicated that Costco has a low cost strategy.[788] Strategy is the process of positioning the organization in the competitive environment and implementing actions to compete successfully. It is a pattern in a stream of decisions.[789] Choosing the types of contributions the firm intends to make to the larger society, precisely whom it will serve, and exactly what it will provide to others are conventional ways in which the firm begins the pattern of decisions and corresponding implementations that define its strategy.

Strategy positions the organization in the competitive environment and implements actions to compete successfully.

The strategy process is ongoing. It should involve individuals at all levels of the firm to ensure that there is a recognizable, consistent pattern—yielding a superior capability over rivals—up and down the firm and across all of its activities. This recognizable pattern involves many facets to develop a sustainable and unique set of dynamic capabilities. Note how Costco has established itself as a low-cost provider and has consistently held to minimizing costs while valuing employees and customers. Costco has positioned itself for superior capability, and it has developed a consistent pattern of decisions to ensure future success.

Obviously, a successful strategy does not evolve in a vacuum but is driven by the goals emphasized, the size of the enterprise, the nature of the technology used by the firm, and its setting as well as the structure used to implement the strategy. In this chapter, we will emphasize the development of dynamic capabilities via organizational learning as an enduring feature of a successful strategy. We emphasize organizational learning because learning will be critical for firms competing in the 21st century.

Organizational learning is the process of acquiring knowledge and using information to adapt successfully to changing circumstances. For organizations to learn, they must engage in knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention in adapting successfully to changing circumstances.[790] In simpler terms, organizational learning involves the adjustment of the actions based on the organization's experience and that of others. The challenge is doing to learn and learning to do.

Organizational learning is the process of knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention.

How Organizations Acquire Knowledge Firms obtain information in a variety of ways and at different rates during their histories. Perhaps the most important information is obtained from sources outside the firm at the time of its founding. During the firm's initial years, its managers copy, or mimic, what they believe are the successful practices of others.[791] As they mature, however, firms can also acquire knowledge through experience and systematic search.

Mimicry Mimicry is important to the new firm because (1) it provides workable, if not ideal, solutions to many problems; (2) it reduces the number of decisions that need to be analyzed separately, allowing managers to concentrate on more critical issues; and (3) it establishes legitimacy or acceptance by employees, suppliers, and customers and narrows the choices calling for detailed explanation. One of the key factors involved in examining mimicry is the extent to which managers attempt to isolate cause-effect relationships. Simply copying others without attempting to understand the issues involved often leads to failure. When mimicking others, managers need to adjust for the unique circumstances of their corporation. See OB Savvy 17.1 for tips about Process Benchmarking.

Experience A primary way to acquire knowledge is through experience. All organizations and managers can learn in this manner. Besides learning-by-doing, managers can also systematically embark on structured programs to capture the lessons to be learned from failure and success. For instance, a well-designed research and development program allows managers to learn as much through failure as through success.[792]

Mimicry is the copying of the successful practices of others.

Learning-by-doing in an intelligent way is at the heart of many Japanese corporations, with their emphasis on statistical quality control, quality circles, and other such practices. Many firms have discovered that numerous small improvements can cumulatively add up to a major improvement in both quality and efficiency. The major problem with emphasizing learning-by-doing is the inability to forecast precisely what will change and how it will change. Managers need to believe that improvements can be made, listen to suggestions, and actually implement the changes. It is much more difficult to do than to say, however.[793]

Vicarious Learning Vicarious learning involves capturing the lessons of others' experiences. Typically, successful vicarious learning involves both scanning and grafting.[794]

Scanning involves looking outside the firm and bringing back useful solutions. At times, these solutions are applied to recognized problems. More often, these solutions float around management until they are needed to solve a problem.[795] Astute managers can contribute to organizational learning by scanning external sources, such as competitors, suppliers, industry consultants, customers, and leading firms. For instance, by reverse engineering the competitor's products (developing the engineering drawings and specifications from the existing product), an organization can quickly match all standard product features. By systematically exploring the proposed developments from suppliers, a firm may become a lead user and be among the first to capitalize on the developments of suppliers.

Scanning is looking outside the firm and bringing back useful solutions to problems.

Grafting is the process of acquiring individuals, units, or firms to bring in useful knowledge. Almost all firms seek to hire experienced individuals from other firms simply because experienced individuals may bring with them a completely new series of solutions. Contracting out or outsourcing is the reverse of grafting and involves asking outsiders to perform a particular function. Whereas virtually all organizations contract out and outsource, the key question for managers is often what to keep.

Information Distribution and Interpretation Once information is obtained, managers must establish mechanisms to distribute relevant information to the individuals who may need it. A primary challenge in larger firms is to locate quickly who has the appropriate information and who needs specific types of information.

Although data collection is helpful, it is not enough. Data are not information; the information must be interpreted. Information within organizations is a collective understanding of the firm's goals and of how the data relate to one of the firm's stated or unstated objectives within the current setting. Unfortunately, a number of common problems often thwarts the process of developing multiple interpretations.[796]

Chief among the problems of interpretation are self-serving interpretations. Among managers, the ability to interpret events, conditions, and history to their own advantage is almost universal. Managers and employees alike often see what they have seen in the past or see what they want to see. Rarely do they see what is or can be.

Retention Organizations contain a variety of mechanisms that can be used to retain useful information.[797] Six important retention mechanisms are individuals, transformation procedures, formal structures, ecology, external archives, and internal information technologies (IT).

Individuals are the most important storehouses of information for organizations. Organizations that retain a large and comparatively stable group of experienced individuals are expected to have a higher capacity to acquire, retain, and retrieve information. Collectively, these individuals hold memory via rich, vivid, and meaningful stories that outlive those who experienced the event.

Transformation mechanisms such as documents, rule books, written procedures, and even standard but unwritten methods of operation are all transformation mechanisms used to store accumulated information. In cases where operations are extremely complex but rarely needed, written sources of information are often invaluable.

The organization's formal structure and the positions in an organization are less obvious but equally important mechanisms for storing information. When an aircraft lands on the deck of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, there are typically dozens of individuals on the deck, apparently watching the aircraft land. Each person on the deck is there for a specific purpose. Each can often trace his or her position to a specific accident that would not have occurred had some individual originally been assigned that position.

Physical structures (or ecology, in the language of learning theorists) are potentially important mechanisms used to store information. For example, a traditional way of ordering parts and subcomponents in a factory is known as the "two-bin" system. One bin is always kept in reserve. Once an individual opens the reserve bin, he or she automatically orders replacements. In this way, the plant never runs out of components.

External archives can be tapped to provide valuable information in larger organizations. Former employees, stock market analysts, suppliers, distributors, and the media can be important sources of valuable information. These external archives are important because they may provide a view of events quite different from that held in the organization.

Finally, internal information technology of a firm, or its IT System, can provide a powerful and individually tailored mechanism for storing information. All too often, however, managers are not using their IT systems strategically and are not tapping into them as mechanisms for retention.

As this quick overview of strategy and learning suggests, there are many strategies and many ways to learn. Historically, these two concepts have been discussed separately. Often strategy is linked to economic perspectives of the firm whereas learning is discussed with organizational change. Today, however, many OB scholars recognize that to compete successfully in the 21st century global economy, individuals, units, and firms will need to learn continually. A firm based in a developed nation cannot successfully compete with firms based in developing counties just by being more efficient any more than an individual in Western Europe or North America can afford to work for the same wages as laborers from developing countries. There is just too much difference in the labor rates.

Production technology now spreads globally; transportation of goods is cheap and the delivery of many services cuts across national boundaries. However, this does not mean firms in developed nations are doomed. Firms can know more about their local markets; they can carefully select what they produce, what services they provide, what they buy, and how to build capability. They must learn and use their strategy to provide the necessary balance between exploration and exploitation of new ideas.[798] They must be capable of sustained learning at the organizational level to capture the lessons from exploring new technologies and exploiting existing markets.[799]

It is important to emphasize that sustaining a competitive strategy with consistent learning involves more than just a commitment by individuals; it calls for a systematic adjustment of the organization's structure and processes to alterations in the size and scope of operations, the technology selected, and the environmental setting. The process involved in making these dynamic adjustments is known as organizational design.

Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration.[800] It goes beyond just indicating who reports to whom and what types of jobs are contained in each department. The design process takes the basic structural elements and molds them to the firm's desires, demands, constraints, and choices. The choice of an appropriate organizational design is contingent upon several factors, including the size of the firm, its operations and information technology, its environment, and, of course, the strategy it selects for growth and survival.

Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration for an organization.

For example, IBM's senior management has selected a form of organization for each component of IBM that matches that component's contribution to the whole. The overall organizational design matches the technical challenges facing IBM, allows it to adjust to new developments, and helps it shape its competitive landscape. Above all, the design promotes the development of individual skills and abilities, but different designs stress different skills and abilities. See, for instance, the activities IBM supports for Naoki Abe in its Yorktown Research Center. As we discuss each major contingency factor, we will highlight the design option the firm's managers need to consider and link these options to aspects of innovation and learning.[801]

To show the intricate intertwining of strategy and organizational design, it is important to reiterate and extend the dualistic notion of strategy.[802] Recall that strategy is a positioning of the firm in its environment to provide it with the capability to succeed. Strategy is also a pattern in the stream of decisions. Here we will emphasize that what the firm intends to do must be backed up by capabilities for implementation in a setting that facilitates success.

Historically, executives were told that firms had available a limited number of economically determined generic strategies that were built upon the foundations of such factors as efficiency and innovation.[803] If the firm wanted efficiency it should adopt the machine bureaucracy (many levels of management backed with extensive controls replete with written procedures). If it wanted innovation, it should adopt a more organic form (fewer levels of management with an emphasis on coordination). Today the world of corporations is much more complex and executives have found much more sophisticated ways of competing.

Now many senior executives emphasize the skills and abilities that their firms need to compete and to remain agile and dynamic in a rapidly changing world.[804] The structural configuration or organizational design of the firm should not only facilitate the types of accomplishment desired by senior management, but also allow individuals to experiment, grow, and develop competencies so that the strategy of the firm can evolve.[805] Over time, the firm may develop specific administrative and technical skills as middle and lower-level managers institute minor adjustments to solve specific problems. As they learn, so can their firms if the individual learning of employees can be transferred across and up the organization's hierarchy. As the skills of employees and managers develop, they may be recognized by senior management and become a foundation for revisions in the overall strategy of the firm.

With astute senior management, the firm can co-evolve. That is, the firm can adjust to both internal and external changes even as it shapes some of the challenges facing it. Co-evolution is a process.[806] One aspect of this process is repositioning the firm in its setting as the setting changes. A shift in the environment may call for adjusting the firm's scale of operations. Senior management can also guide the process of positioning and repositioning in the environment. Co-evolution may call for changes in technology. For instance, a firm can introduce new products into new markets. It can change parts of its environment by joining with others to compete. However, senior management must also have the necessary internal capabilities if it is to shape its environment. It cannot introduce new products without extensive product development capabilities or rush into a new market it does not understand. Shaping capabilities via the organization's design is a dynamic aspect of co-evolution.

The second aspect of strategy is a pattern in the stream of decisions. In a recent poll of some 750 CEOs, Samuel Palmisano, CEO of IBM, reported that two-thirds of the respondents reported being inundated with change and new competitors. Most saw that their primary focus would be to adjust their firm's processes, management, and culture to the new learning challenges. Most called for collaboration with other firms and suggested that they would emphasize learning to innovate.[807]

The organizational design can reinforce a focus and provide a setting for the continual development of employee skills. As the environment, strategy, and technology shift, we will see shifts in design and the resulting capabilities. IBM was once known as big blue, a button-down, white-shirt, blue-tie-and-black-shoe, second-to-market imitator with the bulk of its business centered on mainframe computers. The company is now a major hub in e-commerce and is on the cutting edge as an integrator across systems, equipment, and service. To remain successful, IBM will continue to rely upon the willingness of employees to take chances, refine their skills, and work together creatively.

The interplay of forces helps mold and shape the behavior in organizations and the development of competencies through a firm's organizational design. Even with co-evolution, managers must maintain a recognizable pattern of choices in the design that leads to accomplishing a broadly shared view of where the firm is going.

Most organizations want to grow, and as they grow, the organizational design of the firm needs to be attuned to its size. For many reasons, large organizations cannot be bigger versions of their smaller counterparts. When the number of individuals in a firm is increased arithmetically, the number of possible interconnections between these individuals increases geometrically. In other words, the direct interpersonal contact among all members in an organization must be managed. The design of small firms is directly influenced by its core operations technology, whereas larger firms have many core operations technologies in a wide variety of much more specialized units. In short, larger organizations are often more complex than smaller firms. While all larger firms are bureaucracies, smaller firms need not be. In larger firms, additional complexity calls for a more sophisticated organizational design. Such is not the case for the small firm.

Smaller Size and the Simple Design The simple design is a configuration involving one or two ways of specializing individuals and units. Vertical specialization and control typically emphasize levels of supervision without elaborate formal mechanisms (for example, rulebooks and policy manuals), and the majority of the control resides in the manager. Thus, the simple design tends to minimize bureaucracy and rest more heavily on the leadership of the manager.

The simple design pattern is appropriate for many small firms, such as family businesses, retail stores, and small manufacturing firms.[808] The strengths of the simple design are simplicity, flexibility, and responsiveness to the desires of a central manager—in many cases, the owner. Because a simple design relies heavily on the manager's personal leadership, however, this configuration is only as effective as is the senior manager.

For example, B&A Travel is a comparatively small travel agency owned by Helen Druse. Reporting to Helen is a part-time staff member, Jane Bloom, for accounting and finance. Joan Wiland heads the operations arm. Joan supervises eight travel agents and keeps the dedicated computer system operating. Each of the lead travel agents specializes in a geographical area, and all but Sue Connely and Bart Merve take client requests for all types of trips. Sue is in charge of three major business accounts, and Bart heads a tour operation. Both of these agents report directly to Helen. Coordination is achieved through their dedicated intranet and Internet connections. Joan uses weekly meetings and a lot of personal contact by Helen and Joan to coordinate everyone. Control is enhanced by the computerized reservation system they all use. Helen makes sure each agent has a monthly sales target, and she routinely chats with important clients about their level of service. Helen realizes that developing participation from even the newest associate is an important tool in maintaining a "fun" atmosphere.

Read the Leaders on Leadership feature for this chapter and the story about G24i's leadership team. This small high-tech producer in the solar-power business has a simple structure to implement its strategy. The backgrounds of the leadership team clearly reflect the competencies they bring to help this new and innovative start-up to succeed.[809]

The Perils of Growth and Age As organizations age and begin to grow beyond their simple structure they become more rigid, inflexible, and resistant to change.[810] Managerial scripts become routines, and both managers and employees begin to believe their prior success will continue into the future without an emphasis on innovation or learning. The organization or department becomes subject to routine scripts.

A managerial script is a series of well-known routines for problem identification and alternative generation and analysis common to managers within a firm.[811] Different organizations have different scripts, often based on what has worked in the past. In a way, the script is a ritual that reflects the "memory banks" held by the corporation. Managers become bound by what they have seen. The danger is that they may not be open to what actually is occurring. They may be unable to unlearn.

A managerial script is a series of well-known routines for problem identification and alternative generation and analysis common to managers within a firm.

The script may be elaborate enough to provide an apparently well-tested series of solutions based on the firm's experience. Typically, older firms are structured for efficiency. Their organizational design emphasizes repetition, volume processing, and routine. In order to learn, the organization needs to be able to unlearn, switch routines to obtain information quickly, and provide various interpretations of events rather than just tap into external archives.

Few managers question a successful script. Consequently, they start solving today's problems with yesterday's solutions. Managers are trained, both in the classroom and on the job, to initiate corrective action within the historically shared view of the world. That is, managers often initiate small, incremental improvements based on existing solutions instead of creating new approaches to identify underlying problems.

For larger organizations a key challenge is eliminating the vertical, horizontal, external, and geographic barriers that block desired action, innovation, and learning.[812] These barriers include an overemphasis on vertical relations that can block communication up and down the firm; an overemphasis on functions, product lines, or organizational units that blocks effective coordination; maintaining rigid lines of demarcation between the firm and its partners that isolate it from others; and reinforcing natural cultural, national, and geographical borders that can limit globally coordinated action. In breaking down such barriers, the goal is not necessarily to eliminate them altogether, but to make them more permeable.[813]

There are several major factors associated with the inability to dynamically co-evolve and develop a cycle with positive benefits, but three are obvious from current research.[814] One is organizational inertia. It is very difficult to change an organization, and the larger the organization, the more inertia it often has. A second is hubris. Too few senior executives are willing to challenge their own actions or those of their firms because they see a history of success. A third is the issue of detachment. Executives often believe they can manage far-flung, diverse operations through analysis of reports and financial records. They lose touch and fail to make the needed unique and special adaptations required of all firms.

Inertia, hubris, and detachment are common maladies, but they are not the automatic fate of all corporations. Firms can successfully co-evolve. As we have repeatedly demonstrated, managers are constantly trying to reinvent their firms. They hope to initiate a benefit cycle—a pattern of successful adjustment followed by further improvements.[815] General Mills, IBM, Cisco, and Microsoft are examples of firms experiencing a benefit cycle. In this cycle, the same problems do not keep recurring as the firm develops adequate mechanisms for learning. The firm has few major difficulties with the learning process, and managers continually attempt to improve knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory.

Although the design for an organization should reflect its size, it must also be adjusted to fit technological opportunities and requirements.[816] Successful organizations are said to arrange their internal structures to meet the dictates of their dominant "operations technologies" or workflows and, more recently, information technology opportunities.[817] Operations technology is the combination of resources, knowledge, and techniques that creates a product or service output for an organization.[818] Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.[819]

Operations technology is the combination of resources, knowledge, and techniques that creates a product or service output for an organization.

Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.

As researchers in OB have charted the links between operations technology and organizational design, two common classifications for operations technology have received considerable attention: Thompson's and Woodward's classifications.

Thompson's View of Technology James D. Thompson classified technologies based on the degree to which the technology could be specified and the degree of interdependence among the work activities with categories called intensive, mediating, and long-linked.[820] Under intensive technology, there is uncertainty as to how to produce desired outcomes. A group of specialists must be brought together interactively to use a variety of techniques to solve problems. Examples are found in a hospital emergency room or a research and development laboratory. Coordination and knowledge exchange are of critical importance with this kind of technology.

Mediating technology links parties that want to become interdependent. For example, banks link creditors and depositors and store money and information to facilitate such exchanges. Whereas all depositors and creditors are indirectly interdependent, the reliance is pooled through the bank. The degree of coordination among the individual tasks with pooled technology is substantially reduced, and information management becomes more important than coordinated knowledge application.

Under long-linked technology, also called mass production or industrial technology, the way to produce the desired outcomes is known. The task is broken down into a number of sequential steps. A classic example is the automobile assembly line. Control is critical, and coordination is restricted to making the sequential linkages work in harmony.

Joan Woodward also divides technology into three categories: small-batch, mass production, and continuous-process manufacturing.[821] In units of small-batch production, a variety of custom products are tailor-made to fit customer specifications, such as tailor-made suits. The machinery and equipment used are generally not very elaborate, but considerable craftsmanship is often needed. In mass production, the organization produces one or a few products through an assembly-line system. The work of one group is highly dependent on that of another, the equipment is typically sophisticated, and the workers are given very detailed instructions. Automobiles and refrigerators are produced in this way.

Organizations using continuous-process technology produce a few products using considerable automation. Classic examples are automated chemical plants and oil refineries. Millennium Chemicals' operations are a good example of what Woodward called continuous-process manufacturing. As the Ethics in OB suggests, innovative firms such as Millennium Chemicals are infusing ethics into day-to-day operations and making ethics a part of a recognizable pattern we have called strategy.

From her studies, Woodward concluded that the combination of structure and technology was critical to the success of the organizations. When technology and organizational design were matched properly, a firm was more successful. Specifically, successful small-batch and continuous-process plants had flexible structures with small workgroups at the bottom; more rigidly structured plants were less successful. In contrast, successful mass-production operations were rigidly structured and had large workgroups at the bottom. Since Woodward's studies, various other investigations supported this technological imperative. Today we recognize that operations technology is just one factor involved in the success of an organization.[822]

The influence of operations technology is clearly seen in small organizations and in specific departments within large firms. In some instances, managers and employees simply do not know the appropriate way to service a client or to produce a particular product. This is an extreme example of Thompson's intensive type of technology, and it may be found in some small-batch processes where a team of individuals must develop a unique product for a particular client.

Mintzberg suggests that at these technological extremes, the "adhocracy" may be an appropriate design.[823] An adhocracy is characterized by

few rules, policies, and procedures;

substantial decentralization;

shared decision making among members;

extreme horizontal specialization (as each member of the unit may be a distinct specialist);

few levels of management; and

virtually no formal controls.

Adhocracy emphasizes shared, decentralized decision making; extreme horizontal specialization; few levels of management; the virtual absence of formal controls; and few rules, policies, and procedures.

This design emphasizes innovation and learning. The adhocracy is particularly useful when an aspect of the firm's operations technology presents two sticky problems:

the tasks facing the firm vary considerably and provide many exceptions, as in a management consulting firm, or

problems are difficult to define and resolve.[824]

The adhocracy places a premium on professionalism and coordination in problem solving.[825] Large firms may use temporary task forces, form special committees, and even contract with consulting firms to provide the creative problem identification and problem solving that the adhocracy promotes. For instance, Microsoft creates autonomous departments to encourage talented employees to develop new software programs. Allied Chemical and 3M set up quasi-autonomous groups to work through new ideas.

We should note, however, that the adhocracy is notoriously inefficient. Further, many managers are reluctant to adopt this form because they appear to lose control of day-to-day operations. The implicit strategy consistent with the adhocracy is a stress on quality and individual service as opposed to efficiency. With more advanced information technology, firms are beginning to combine an adhocracy with bureaucratic elements based on advanced information systems.

Recall that we defined information technology as the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information.[826] Information technology (IT), the Web, and the computer are virtually inseparable and they have fundamentally changed the organization design of firms to capture new competencies.[827] While some suggest that IT refers only to computer-based systems used in the management of the enterprise, we take a broader view.[828] With substantial collateral advances in telecommunication options, advances in the computer as a machine are much less profound than how information technology is transforming how firms manage all of their parts.

From an organizational standpoint, IT can be used, among other things, as a partial substitute for some operations as well as some process controls and impersonal methods of coordination. IT has a strategic capability as well as a capability for transforming information to knowledge. For instance, most financial firms could not exist without IT, because it is now the base for the industry. Early adopters created new segments of the industry with both major contributions to our economy and major new threats. With IT, exotic international financial products are available today, which did not exist 20 years ago. And financial institutions created completely new aspects of their industry based on IT, such as exotic derivatives; it is now painfully obvious that these new aspects of the industry outpaced the ability of management to control them. Information technology, just as operations technology, can yield great good or great harm.

IT as a Substitute Old bureaucracies prospered and dominated other firms, in part, because they provided efficient production through specialization and through how they managed their information. Where the organization used mediating technology or long-linked technology, the machine bureaucracy ran rampant. In these firms, rules, policies, and procedures, as well as other process controls, could be rigidly enforced based on very scant information.[829] Such was the case for the U.S. post office: postal clerks had rules telling them how to hold their hands when sorting mail.

In many organizations, the initial implementation of IT displaced the most routine, highly specified, and repetitious jobs.[830] A second wave of substitution replaced process controls and informal coordination mechanisms. Management discovered that written rules, policies, and procedures could be replaced with a decision support system (DSS) that programmed repetitive routine choices into a computer-based system. For instance, if you apply for a credit card, a computer program will check your credit history and other financial information. If your application passes several preset tests, you are issued a credit card.

IT to Add Capability IT has also long been recognized for its potential to add capability.[831] For many years, scholars have talked of using IT to improve the efficiency, speed of responsiveness, and effectiveness of operations. Married to machines, IT became advanced manufacturing technology when computer-aided design (CAD) was combined with computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) to yield the automated manufacturing cell. More complex decision-support systems have provided middle and lower-level managers with programs to aid in analyzing complex problems rather than merely ratifying routine choices. Computer-generated reports now give senior executives the opportunity to track the individual sales performance of every salesperson from top to bottom.

Now instead of substituting for existing operations, or process controls, IT provides individuals deep within the organization with the information they need to plan, coordinate with others, and control their own operations. Connectivity is the watchword of today and with parallel developments in telecommunications, a whole world of electronic commerce, teleconferencing—with combinations of data, pictures, and sound—and cell phones has opened new opportunities for companies. For example, textbooks now provide you with Web exercises and other opportunities for online learning in each chapter.

IT systems can also empower individuals, expanding their jobs and making them both interesting and challenging. The emphasis on narrowly defined jobs replete with process controls imposed by middle management can be transformed to broadly envisioned, interesting jobs based on IT-embedded processes with output controls. The IT system can handle the routine operations while individuals deep within the organization deal with the exceptions. For example, you can order plumbing supplies to update a bath or kitchen from Moen directly. Their Web site provides pictures of the products, specifications, and a phone number if you need help. The Moen representatives are there to provide the needed technical assistance and design help while their Web site provides the product information.[832]

For the production segments of firms using long-linked technology such as in auto assembly plants and canneries, IT is now linked to total quality management (TQM) programs and embedded in the machinery. Data on operations now transform into knowledge of operations and are used to improve quality and efficiency. This means that firms have had to rethink their view of employees as brainless robots. To make TQM work with IT, all employees must plan, do, and control. Combining IT and TQM with empowerment and participation is fundamental for success.[833]

The Virtual Organization and IT Opportunities Shortly before the turn of the last century, e-business exploded upon the scene.[834] Today e-business is integrated into the virtual organization just as on-site project teams morphed into virtual project teams.

E- Business and IT Whether it is business to business (B2B) or business to consumers (B2C), there is a whole new set of firms with information technology at the core of their operations. One of the more flamboyant early entrants to the B2C world is the now-familiar Amazon.com. Opened in 1995 to sell books directly to customers via the Internet, it rapidly expanded to toys and games, health and beauty products, groceries, computers and video games, as well as cameras and photography. It is now a virtual general store with one of the best-recognized Web site addresses available.

It is interesting to examine the transformation in the design of this firm to illustrate the notion of co-evolution and the ability to learn with advanced IT. Initially, Amazon.com was organized as a simple structure. As it grew, it became more complex by adding divisions devoted to each of its separate product areas. To remain flexible and promote growth in both the volume of operations and the capabilities of employees, it did not develop an extensive bureaucracy. There are still very few levels of management. It built separate organizational components based on product categories (divisional structure) with minimal rules, policies, and procedures. In other words, the organizational design it adopted appeared relatively conventional.[835]

What was not conventional was the use of IT for learning about customers and for coordinating and tracking operations. Although their Web site is not particularly advanced technically, you can easily order a book, track the delivery, and feel confident it will arrive as promised. In recent years, Amazon.com has used its IT prowess to develop strategic alliances with brick and mortar firms and it effectively changed the competitive landscape.

In comparison to Amazon.com, many other new dot-com firms adopted a variation of the adhocracy as their design pattern. The thinking was that e-business was fundamentally different from the old bricks-and-mortar operations. Thus, an entirely new structural configuration was needed to accommodate the development of new e-products and services. The managers of these firms forgot two important liabilities of the adhocracy as they grew. First, there are limits on the size of an effective adhocracy. Second, the actual delivery of their products and services did not require continual product innovation but rested more on responsiveness to clients and maintaining efficiency. The design did not deliver what they needed. In common terms they had great Web sites, but they were grossly inefficient. Many of these businesses died almost as quickly as they were formed.

The Emergence of the Virtual Organization As IT has become widespread, firms are finding it can be the basis for a new way to compete. Some executives have started to develop "virtual organizations."[836] A virtual organization is an ever-shifting constellation of firms, with a lead corporation, that pools skills, resources, and experiences to thrive jointly. This ever-changing collection most likely has a relatively stable group of actors (usually independent firms) that normally includes customers, research centers, suppliers, and distributors all connected to each other. The lead firm possesses a critical competence that all need and therefore directs the constellation. While this critical competence may be a key operations technology or access to customers, it always includes IT as a base for connecting the firms. Across time, members of the constellation come and go during shifts in technology or alterations in environmental conditions. It is also important to stress that key customers are an integral part of a virtual organization. Not only do customers purchase from the company, they also participate in the development of new products and services. Thus, the virtual organization co-evolves by incorporating many types of firms.

A virtual organization is an ever-shifting constellation of firms, with a lead corporation, that pool skills, resources, and experiences to thrive jointly.

The virtual organization works if it operates by some unique rules and is led in a most untypical way. First, the production system that yields the products and services that customers desire needs to be a partner network among independent firms where they are bound together by mutual trust and collective survival. As customers desire change, the proportion of work done by any member firm might also change and the membership itself may change. In a similar fashion, the introduction of a new operations technology could shift the proportion of work among members or call for the introduction of new members.

Second, this partner network needs to develop and maintain (a) an advanced information technology (rather than just face-to-face interaction), (b) trust and cross-owning of problems and solutions, and (c) a common shared culture. Developing these characteristics is a very tall order, but the virtual organization can be highly resilient, extremely competent, innovative, and reasonably efficient—characteristics that are usually trade-offs. The virtual organization can effectively compete on a global scale in very complex settings using advanced operations and information technologies.

The role of the lead firm is also quite unusual and actually makes a network of firms a virtual organization. The lead firm must take responsibility for the whole constellation and coordinate the actions and evolution of autonomous member firms. Executives in the lead firm need to have the vision to see how the network of participants will both effectively compete with consistent enough patterns to be recognizable and still rapidly adjust to technological and environmental changes. Executives should not only communicate this vision and inspire individuals in the independent member firms, but also treat members as if they are volunteers. To accomplish this across independent firms, the lead corporation and its members need to rethink how they are internally organized and managed.[836]

Even before the complete development of a virtual organization, more than likely you will be involved with a "virtual" network of task forces and temporary teams to both define and solve problems. Here the members will only connect electronically. Recent work on participants of the virtual teams suggests you will need to rethink what it means to "manage." Instead of telling others what to do, you will need to treat your colleagues as unpaid volunteers who expect to participate in governing the meetings and who are tied to the effort only by a commitment to identify and solve problems.[837] Mastering Management provides guidelines to think about when managing a project in a virtual environment.[838]

An effective organizational design also reflects powerful external forces as well as size and technological factors. Organizations, as open systems, need to receive input from the environment and in turn to sell output to their environment. Therefore, understanding the environment is important.[839]

The general environment is the set of cultural, economic, legal-political, and educational conditions found in the areas in which the organization operates. Firms expanding globally encounter multiple general environments. Once, firms could separate foreign and domestic operations into almost separate operating entities, but this is rarely the case now. Today consumers and employees are responding to a series of global issues such as global warming, fair trade, and sustainability. Firms sourcing from developing countries are changing their sourcing practices to conform to expectations in developed nations, as illustrated by the Fairtrade movement. Here, farmers are encouraged to develop sustainable farming and are paid more for their products.[840]

The general environment is the set of cultural, economic, legal-political, and educational conditions found in the areas in which the organization operates.

The owners, suppliers, distributors, government agencies, and competitors with which an organization must interact to grow and survive constitute its specific environment. A firm typically has much more choice in the composition of its specific environment than its general environment. Although it is often convenient to separate the general and specific environmental influences on the firm, managers need to recognize the combined impact of both. Choosing some businesses, for instance, means entering global competition with advanced technologies.

A basic concern to address when analyzing the environment of the organization is its complexity. A more complex environment provides an organization with more opportunities and more problems. Environmental complexity refers to the magnitude of the problems and opportunities in the organization's environment, as evidenced by three main factors: the degree of richness, the degree of interdependence, and the degree of uncertainty stemming from both the general and the specific environment.

Environmental Richness Overall, the environment is richer when the economy is growing, when individuals are improving their education, and when everyone that the organization relies upon is prospering. For businesses, a richer environment means that economic conditions are improving, customers are spending more money, and suppliers (especially banks) are willing to invest in the organization's future. In a rich environment, more organizations survive, even if they have poorly functioning organizational designs. A richer environment is also filled with more opportunities and dynamism—the potential for change. The organizational design must allow the company to recognize these opportunities and capitalize on them.

The opposite of richness is decline. For business firms, the current general recession is a good example of a leaner environment. While corporate reactions do vary, it is instructive to examine typical responses to decline. In the United States, firms have traditionally reacted to decline first by issuing layoffs to non-supervisory workers and by moving the layoffs up the organizational ladder as the environment becomes leaner. Many European firms find it difficult to cut full-time employees quickly because of European employment laws. In sustained periods of decline, many European firms therefore turn to national governments for help. Much like U.S.-based firms, European-based firms view changes in organizational design as a last but increasingly necessary resort as they compete globally.

The specific environment is the set of owners, suppliers, distributors, government agencies, and competitors with which an organization must interact to grow and survive.

Environmental complexity is the magnitude of the problems and opportunities in the organization's environment as evidenced by the degree of richness, interdependence, and uncertainty.

Environmental Interdependence The link between external interdependence and organizational design is often subtle and indirect. The organization may co-opt powerful outsiders by including them. For instance, many large corporations have financial representatives from banks and insurance companies on their boards of directors. The organization may also adjust its overall design strategy to absorb or buffer the demands of a more powerful external element. Perhaps the most common adjustment is the development of a centralized staff department to handle an important external group. For instance, few large U.S. corporations lack some type of centralized governmental relations group. Where service to a few large customers is critical, the organization's departmentation is likely to switch from a functional to a divisionalized form.[841]

Uncertainty and Volatility Environmental uncertainty and volatility can be particularly damaging to large bureaucracies. In times of change, investments quickly become outmoded, and internal operations no longer work as expected. The obvious organizational design response to uncertainty and volatility is to opt for a more flexible organic form. At the extremes, movement toward an adhocracy may be important. However, these pressures may run counter to those that come from large size and operations technology. In these cases, it may be too hard or too time consuming for some organizations to make the design adjustments. Thus, the organization may continue to struggle while adjusting its design just a little bit at a time. Some firms can deal with the conflicting demands from environmental change and need for internal stability by developing alliances.

In today's complex global economy, organizational design must go beyond the traditional boundaries of the firm.[842] Firms must learn to co-evolve by altering their environment. Two ways are becoming more popular: (1) the management of networks, and (2) the development of alliances. Many North American firms are learning from their European and Japanese counterparts to develop networks of linkages to the key firms they rely upon. In Europe, for example, one finds informal combines or cartels. Here, competitors work cooperatively to share the market in order to decrease uncertainty and improve favorability for all. Except in rare cases, these arrangements are often illegal in the United States.

In Japan, the network of relationships among well-established firms in many industries is called a keiretsu. There are two common forms. The first is a bank-centered keiretsu, in which firms link to one another directly through cross-ownership and historical ties to one bank. The Mitsubishi group is a good example of a company that grew through cross-ownership. In the second type, a vertical keiretsu, a key manufacturer is at the hub of a network of supplier firms or distributor firms. The manufacturer typically has both long-term supply contracts with members and cross-ownership ties. These arrangements help isolate Japanese firms from stockholders and provide a mechanism for sharing and developing technology. Toyota is an example of a firm at the center of a vertical keiretsu.

A specialized form of network organization is evolving in U.S.-based firms as well. Here, the central firm specializes in core activities, such as design, assembly, and marketing, and works with a small number of participating suppliers on a long-term basis for both component development and manufacturing efficiency. The central firm is the hub of a network where others need it more than it needs any other member. Although Nike was a leader in the development of these relationships, now it is difficult to find a large U.S. firm that does not outsource extensively. Executives seeking to find cheap sources of foreign labor often justify outsourcing from the U.S. firms. However, as a design option, managers should examine how this alternative fits with the firm's strategy and technology as well. For instance, if the firm markets high quality products matched with service, outsourcing may be inconsistent with the service requirements needed for success. Customers could move to firms that do not outsource service.

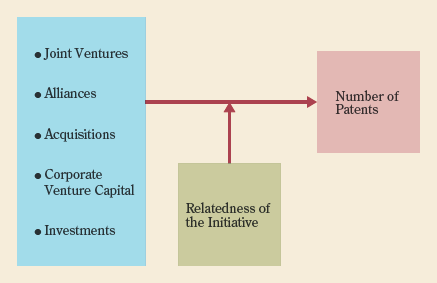

Being at the hub of a network can provide a greater opportunity to innovate and gain greater financial returns. Hiring capable individuals with experience in developing new products helps. Combine these two traits, and firms generate substantially more innovation and gain substantially more financial returns.[843]

More extreme variations of network design are emerging to meet apparently conflicting environmental, size, and technological demands simultaneously. Firms are spinning off staff functions to reduce their overall size and take advantage of new IT options. For example, many call centers for computer technology support are outsourced to India. With too much outsourcing, firms become too highly dependent upon others, lose the ability to be flexible and respond to new opportunities, and may lose valuable information. For example, the use of foreign call centers cuts information flowing from customers to the core firm. With these new environmental challenges and technological opportunities, firms must choose and not just react blindly.

Another option is to develop interfirm alliances, which are cooperative agreements or joint ventures between two independent firms.[844] Often, these agreements involve corporations that are headquartered in different nations. In high-tech areas, such as robotics, semiconductors, advanced materials (ceramics and carbon fibers), and advanced information systems, a single company often does not have all of the knowledge necessary to bring new products to the market. Alliances are quite common in such high-technology industries. Via their international alliances, high-tech firms seek to develop technology and to ensure that their solutions standardize across regions of the world.

Developing and effectively managing an alliance is a managerial challenge of the first order. Firms are asked to cooperate rather than compete. The alliance's sponsors normally have different and unique strategies, cultures, and desires for the alliance itself. Both the alliance managers and sponsoring executives must be patient, flexible, and creative in pursuing the goals of the alliance and each sponsor. It is little wonder that some alliances are terminated prematurely.[845]

Of course, alliances are but one way of altering the environment. The firm can also invest in the projects of other firms via corporate venture capital. It may acquire other companies to bring their expertise directly into the firm. All of these can be beneficial.[846] However, these initiatives need to be related to the strategy of the firm and its technology. Examine the Research Insight to see how much firms learned from the use of joint ventures, established alliances and acquisitions (both partial and complete).[847]

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 17.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 17 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

Why are strategy and organizational learning important?

Strategy is the process of positioning the organization in the competitive environment and implementing actions to compete successfully. It is a pattern in a stream of decisions.

Organizational learning is the process of acquiring knowledge and using information to adapt successfully to changing circumstances.

For organizations to learn, they must engage in knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational retention in adapting successfully to changing circumstances.

Firms use mimicry, experience, vicarious learning, scanning, and grafting to acquire information.

Firms established mechanisms to convert information into knowledge. Chief among the problems of interpretation are self-serving interpretations.

Firms retain information via individuals, transformation mechanisms, formal structure, physical structure, external archives, and their IT system.

To compete successfully, individuals, units, and firms will need to constantly learn because of changes in the scope of operations, technology, and the environment.

What is organizational design, and how is it linked to strategy?

Organizational design is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration for an organization.

Organizational design is a way to implement the positioning of the firm in its environment.

Organizational design provides a basis for a consistent stream of decisions.

Strategy and organizational design are interrelated, and must evolve with changes in size, technology, and the environment.

The design of a large organization is far more complex than that of a small firm. Smaller firms often adopt a simple structure because it works, is cheap, and stresses the influence of the leader.

With growth and aging, firms become subject to routine managerial scripts. Large organizations will need to systematically break down boundaries limiting learning.

How does technology influence organizational design?

Operations technology and organizational design should be interrelated to insure the firm produces the desired goods and/or services.

Adhocracy is an organizational design used in technology intense settings.

Information technology is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge.

IT provides an opportunity to change the design by substitution, for learning, and to capture strategic advantages.

IT forms the basis for the virtual organization.

How does the environment influence organizational design?

Organizations, as open systems, need to receive inputs from the environment and, in turn, to sell outputs to their environment.

The environment is more complex when it is richer and more interdependent with higher volatility and greater uncertainty.

The more complex the environment, the greater the demands on the organization, and firms should respond with more complex designs.

Firms need not stand alone but can develop network relationships and alliances to cope with greater environmental complexity.

By honing the knowledge gained in this text you can develop the skills to compete successfully in the 21st century and become a leader.

Adhocracy (p. 426)

Environmental complexity (p. 431)

General environment (p. 430)

Grafting (p. 417)

Information technology (p. 424)

Interfirm alliances (p. 434)

Organizational design (p. 419)

Organizational learning (p. 416)

Operations technology (p. 424)

Managerial script (p. 422)

Mimicry (p. 417)

Scanning (p. 417)

Simple design (p. 421)

Specific environment (p. 431)

Strategy (p. 416)

Virtual organization (p. 429)

The design of the organization needs to be adjusted to all but ____________. (a) the environment of the firm (b) the strategy of the firm (c) the size of the firm (d) the operations and information technology of the firm (e) the personnel to be hired by the firm

____________ is the combination of resources, knowledge, and techniques that creates a product or service output for an organization. (a) Information technology (b) Strategy (c) Organizational learning (c) Operations technology (d) The general environment (e) The benefit cycle

____________ is the combination of machines, artifacts, procedures, and systems used to gather, store, analyze, and disseminate information for translating it into knowledge (a) The specific environment (b) Strategy (c) Operations technology (d) Information technology (e) Organizational decline

Which of the following is an accurate statement about an adhocracy? (a) The design facilitates information exchange and learning. (b) There are many rules and policies. (c) Use of IT is always minimal. (d) It handles routine problems efficiently. (e) It is quite common in older industries.

The set of cultural, economic, legal-political, and educational conditions in the areas in which a firm operates is called the ____________. (a) task environment (b) specific environment (c) industry of the firm (d) environmental complexity (e) general environment

The segment of the environment that refers to the other organizations with which an organization must interact in order to obtain inputs and dispose of outputs is called ____________. (a) the general environment (b) the strategic environment (c) the learning environment (d) the technological setting (e) the specific environment

____________ are announced cooperative agreements or joint ventures between two independent firms. (a) Mergers (b) Acquisitions (c) Interfirm alliances (d) Adhocracies (e) Strategic configurations

The process of knowledge acquisition, organizational retention, and information distribution and interpretation is called ____________. (a) vicarious learning (b) experience (c) organizational learning (d) an organizational myth (e) a self-serving interpretation

Three methods of vicarious learning are ____________. (a) scanning, grafting, and contracting out (b) grafting, contracting out, and mimicry (c) maladaptive specialization, scanning, and grafting (d) scanning, grafting, and mimicry (e) experience, mimicry, and scanning

Three important factors that block information interpretation are ____________. (a) detachment, scanning, and common myths (b) self-serving interpretations, detachment, and common myths (c) managerial scripts, maladaptive specialization, and common myths (d) contracting out, common myths, and detachment (e) common myths, managerial scripts, and self-serving interpretations

Regarding the organizational design for a small firm compared to a large firm, __________. (a) they are almost the same (b) they are fundamentally different (c) a large firm is just a larger version of a small one (d) the small firm has more opportunity to use information technology

Organizations with well-defined and stable operations technologies ____________. (a) have more opportunity to substitute decision support systems (DSS) for managerial judgment than do firms relying on more variable operations technologies (b) have less opportunity to substitute decision support systems for managerial judgment than do firms relying on more variable operations technologies (c) are less able to develop international alliances (d) are more able to develop international alliances

Adhocracies tend to favor __________. (a) vertical specialization and control (b) horizontal specialization and coordination (c) extensive centralization (d) a rigid strategy

With extensive use of IT, ___________. (a) more staff are typically added (b) firms can use IT (c) firms can move internationally (d) firms can reduce redundancy

Environmental complexity __________. (a) refers to the set of alliances formed by senior management (b) refers to the overall level of problems and opportunities stemming from munificence, interdependence, and volatility (c) is restricted to the general environment of organizations (d) is restricted to other organizations with which an organization must interact in order to obtain inputs and dispose of outputs

The strategy of a firm ________. (a) is the process of positioning the organization in the competitive environment and implementing actions to compete successfully. It is a pattern in a stream of decisions (b) is only a process of positioning the organization to compete (c) is only a pattern in a stream of decisions (d) is a process of acquiring knowledge, organizational retention, and distributing and interpreting information

An organizational alliance is __________. (a) an extreme example of an adhocracy (b) an announced cooperative agreements or joint venture between two independent firms (c) always short-lived (d) a sign of organizational weakness

Copying of the successful practices of others is called __________. (a) mimicry (b) scanning (c) grafting (d) strategy

__________________ is the process of choosing and implementing a structural configuration for an organization. (a) Strategy (b) Organizational design (c) Grafting (d) Scanning

The process of acquiring individuals, units, and/or firms to bring in useful knowledge to the organization is called __________. (a) grafting (b) strategy (c) scanning (d) mimicry

Explain why a large firm could not use a simple structure.

Explain the deployment of IT and its uses in organizations.

Describe the effect operations technology has on an organization from both Thompson's and Woodward's points of view.

What are the three primary determinants of environmental complexity?