Chapter at a glance

Some challenges of leadership and organizational change are quite new; others have been recognized for decades. In this chapter we explore moral persuasion, cultural differences, strategy, and situational change for insights on increasing your effectiveness as a leader. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT IS MORAL LEADERSHIP?

Authentic Leadership

Spiritual Leadership

Servant Leadership

Ethical Leadership

WHAT IS SHARED LEADERSHIP?

Shared Leadership in Work Teams

Shared Leadership and Self-Leadership

HOW DO YOU LEAD ACROSS CULTURES?

The GLOBE Perspective

Culturally Endorsed Leadership Matches

Universally Endorsed Aspects of Leadership

WHAT IS STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP?

Top Management Teams

Multiple-Level Leadership

Leadership Tensions and Complexity

Contexts for Leadership Action

HOW DO YOU LEAD ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE?

Leaders as Change Agents

Phases of Planned Change

Planned Change Strategies

Resistance to Change

John C. Lechleiter, Chairman of the Board and CEO of Eli Lilly, recognized the need for all Lilly employees to become a positive force for a sustained implementation. He challenged all to "Be Inspired. Be Connected. Be a Catalyst." As the CEO, he reiterates the core of the Lilly approach to leadership—prize integrity, strive for excellence, and respect individuals. Lechleiter led the effort for reorientation, linked this reorientation to helping others, challenged individuals to make a difference, and reiterated the Lilly's core values for action.

"Be Inspired. Be Connected. Be a Catalyst."

Under his leadership, Lilly recently revamped its approach to responsibility. He guided the effort to redefine the Lilly framework for social responsibility with the engagement of some 22,000 Lilly employees. His goal was to not only change the face of Lilly in the industry and the communities it serves but also to change the focus of debate about the role of big pharma in U.S. health delivery. Lechleiter recognized that Lilly needed a new positive image. As a result of the effort, Lilly strives to provide "Answers that Matter," via innovative medicines delivered with transparency to tailor therapies to individuals who need them and identify those patients most likely to benefit from Lilly drugs.

Lechleiter admits that while Lilly is moving in the right direction, there are daunting challenges ahead. "Lilly continues to deliver strong financial results ... the pharmaceutical industry, however, continues to face major challenges, and we must act quickly and decisively to address them." He added, "We also recognize the tremendous opportunities that can be created by a company with a clear vision and a commitment to change ... we believe we will provide a continuous flow of high value medicines." flow of high value medicines."

great leaders walk the talk

John C. Lechleiter of Eli Lilly recognizes not only the responsibility to lead ethically but also the power of moral leadership.[631] All of us are aware of recent concerns with moral leadership issues. American International Group (AIG), for example, joined the growing list of firms such as Enron and Merrill Lynch, which at one time had highly questionable leadership. It appears that leaders of various government, religious, and educational entities made decisions based on short-term individual gain rather than long-term collective benefit.

As these problems have gained attention and scrutiny, there has been a stronger emphasis in research on topics including authentic leadership, servant leadership, spiritual leadership, and ethical leadership. These are the topics we will cover in our treatment of moral leadership. Essentially the moral leader is attempting to use transcendent values to stimulate action that is considered beneficial. The challenge of moral leadership starts with who you are and what you think the job of a leader should be.

Authentic leadership essentially argues "know thyself."[632] It involves both owning one's personal experiences (values, thoughts, emotions, and beliefs) and acting in accordance with one's true self (expressing what you really think and believe, and acting accordingly). Although no one is perfectly authentic, authenticity is something to strive for. It reflects the unobstructed operation of one's true or core self. It also underlies virtually all other aspects of leadership, regardless of the particular theory or model involved.

Those high in authenticity are thought to have optimal self-esteem, or genuine, true, stable, and congruent self-esteem, as opposed to fragile self-esteem based on outside responses. Leaders who desire authentic leadership should have genuine relationships with followers and associates and display transparency, openness, and trust.[633] All of these points draw on psychological well-being emphasized in positive psychology literature.[634] For instance, Nelson Mandela is considered authentic leaders.

In positive psychology we find a stress on self-efficacy, which is an individual's belief about the likelihood of successfully completing a specific task; optimism, the expectation of positive outcomes; hope, the tendency to look for alternative pathways to reach a desired goal; and resilience, the ability to bounce back from failure and keep forging ahead. An increase in any one of these is seen as increasing the others. These are important traits for a leader to demonstrate, and are believed to positively influence his or her followers.

Perhaps the most important aspect of authentic leadership is the notion that being a leader begins with you and your perspective on leading others. But being authentic is just one aspect of moral leadership. A second feature is your view of the leader's task.

In contrast to authentic leadership, spiritual leadership can be seen as a field of inquiry within the broader setting of workplace spirituality.[635] Western religious theology and practice coupled with leadership ethics and values provide much of the base for the actions of a spiritual leader. As one might expect with a view based on religion, there is considerable disagreement. One key point of contention is whether spirituality and religion are the same. To some, spirituality stems from their religion. For others, it does not. Researchers note that organized religions provide rituals, routines, and ceremonies, thereby providing a vehicle for achieving spirituality. Of course, one could be considered religious by following religious rituals but could lack spirituality, or one could reflect a strong spirituality without being religious.

![Casual model of spiritual leadership theory. [Source: Lewis W. Fry. Steve Vitucci, and Marie Cedillo, "Spiritual Leadership and Army Transformation: Theory, Measurement, and Establishing a Baseline," The Leadership Quarterly 16.5 (2005), p. 838.]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1401.png)

Figure 14.1. Casual model of spiritual leadership theory. [Source: Lewis W. Fry. Steve Vitucci, and Marie Cedillo, "Spiritual Leadership and Army Transformation: Theory, Measurement, and Establishing a Baseline," The Leadership Quarterly 16.5 (2005), p. 838.]

Even though spiritual leadership does not yet have a strong research base in organizational behavior, there has been some research resulting in the term Spiritual Leadership Theory or SLT. It is a causal leadership approach for organizational transformation designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning organization. Spiritual leadership includes values, attitudes, and behaviors required to intrinsically motivate the leader and others to have a sense of spiritual survival through calling and membership. In other words, the leader and followers experience meaning in their lives, believe they make a difference, and feel understood and appreciated. Such a sense of leader and follower survival tends to create value congruence across the strategic, empowered team and at the individual level; it ultimately encourages higher levels of organizational commitment, productivity, and employee well-being.

Figure 14.1 summarizes a causal model of spiritual leadership. It shows three core qualities of a spiritual leader: Vision—defines the destination and journey, reflects high ideals, encourages hope/faith; Altruistic love—trust/loyalty as well as forgiveness/acceptance/honesty, courage, and humility; Hope/Faith—endurance, perseverance, do what it takes, have stretch goals.

Servant leadership, developed by Robert K. Greenleaf, is based on the notion that the primary purpose of business should be to create a positive impact on the organization's employees as well as the community. In an essay he wrote about servant leadership in 1970, Greenleaf said: "The servant-leader is servant first ... It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead."[636]

The servant leader is attuned to basic spiritual values and, in serving these, assists others including colleagues, the organization, and society. Viewed in this way servant leadership is not a unique example of leadership but rather a special kind of service. The servant leader helps others discover their inner spirit, earns and keeps the trust of their followers, exhibits effective listening skills, and places the importance of assisting others over self-interest. It is best demonstrated by those with a vision and a desire to serve others first, rather than by those seeking leadership roles. Servant leadership is usually seen as a philosophical movement, with the support of the Greenleaf Center for Servant Development, an international nonprofit organization founded by Robert K. Greenleaf in 1964 and headquartered in Indiana. The Center promotes the understanding and practice of servant leadership, holds conferences, publishes books and materials, and sponsors speakers and seminars throughout the world.

While servant leadership is not rooted in OB research, its guiding philosophy is consistent with that of the other aspects of moral leadership discussed here. In this case, the power of modeling service is the basis for influencing others. You lead to serve and ask others to follow; their followership then becomes a special form of service.

There is no simple definition of ethical leadership. However, many believe that ethical leadership is characterized by caring, honest, principled, fair, and balanced choices by individuals who act ethically, set clear ethical standards, communicate about ethics with followers, and reward as well as punish others based on ethical or unethical conduct.[637] Figure 14.2 summarizes the similarities and differences among ethical, authentic, spiritual, and transformational leadership. A key similarity cutting across all these dimensions is role modeling. Altruism, or concern for others, and integrity are also important similarities. Leaders influence others by appealing to transcendent values. In terms of differences, authentic leaders stress authenticity and self-awareness and tend to be more transactional than do the other leaders. Ethical leaders emphasize moral concerns, while spiritual leaders stress visioning, hope, and faith, as well as work as a vocation.

![Similarities and differences between ethical, spiritual, authentic, and transformational theories of leadership. [Source: Michael E. Brown and Linda K. Trevino, "Ethical Leadership: A Review and Future Directions," The Leadership Quarterly 17.6 (December 2006), p. 598.]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1402.png)

Figure 14.2. Similarities and differences between ethical, spiritual, authentic, and transformational theories of leadership. [Source: Michael E. Brown and Linda K. Trevino, "Ethical Leadership: A Review and Future Directions," The Leadership Quarterly 17.6 (December 2006), p. 598.]

Transformational leaders emphasize values, vision, and intellectual stimulation. Taken as a whole, it is clear that any of these related approaches are important and ready for systematic empirical and conceptual development. Even servant leadership would lend itself to further developments.[638] Despite the lack of research, ethical leadership can and should be a driving force for improving today and tomorrow's leaders. Take a look at Ethics in OB for one example.[639]

Shared leadership is defined as a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both. This influence process often involves peer or lateral influence; at other times it involves upward or downward hierarchical influence. The key distinction between shared leadership and traditional models of leadership is that the influence process involves more than just downward influence on subordinates by an appointed or elective leader. Rather, leadership is broadly distributed among a set of individuals instead of centralized in the hands of a single individual who acts in the role of a superior.[640]

Shared leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process through which individuals in teams lead one another.

So far our treatment of leadership has tended to treat it as vertical influence. The notion of vertical leadership is best depicted by the old Westerns of Hollywood fame. A single rider wearing a white hat and riding a white horse—the bad guys wear black hats and ride black horses—arrives in town. The townsfolk are passive and docile while they stand by and watch as the hero cleans up the town, eliminates the bad guys, and declares, "My work here is done." You should recognize that leadership is not restricted to the vertical influence of the lone figure in a white hat but extends to other people as well. Shared and vertical leadership can be more specifically illustrated in terms of self-directing work teams.

Locations of Shared Leadership Leadership can come from outside or inside the team. Within a team, leadership can be assigned to one person, rotate across team members, or even be shared simultaneously as different needs arise across time.[641] Outside the team, leaders can be traditional, formally designated, first-level supervisors, or an outside vertical (top down) leader of a self-managing team whose duties tend to be quite different from those of a traditional supervisor. Often these nontraditional leaders are called "coordinators" or "facilitators." A key part of their job is to provide resources to their unit and serve as a liaison with other units, all without the authority trappings of traditional supervisors. Here, team members tend to carry out traditional managerial/leadership functions internal to the team along with direct performance activities.

The activities or functions vary and could involve a designated team role or even be defined more generally as a process to facilitate shared team performance. In the latter case, you are likely to see job rotation activities, along with skill-based pay, where workers are paid for the mix and depth of skills they possess as opposed to the skills of a given job assignment they might hold.

Desired Shared Conditions The key element to successful team performance is to create and maintain conditions for that performance. While a wide variety of characteristics may be important for the success of a specific effort, five important characteristics have been identified across projects. They include (1) efficient, goal directed effort; (2) adequate resources; (3) competent, motivated performance; (4) a productive, supportive climate; and (5) a commitment to continuous improvement.

Efficient, Goal-Directed Effort The key here is to coordinate the effort both inside and outside the team. Team leaders can play a crucial role and need to coordinate individual efforts with those of the team, as well as team efforts with those of the organization or major subunit. Among other things, such coordination calls for shared visions and goals.

Adequate Resources Teams rely on their leaders to obtain enough equipment, supplies, and so on to carry out the team's goals. These are often handled by the outside facilitator and almost always involve internal and external negotiations enabling the facilitator to do his or her negotiating outside the team.

Competent, Motivated Performance Team members need the appropriate knowledge, skills, abilities, and motivation to perform collective tasks well. Leaders may be able to influence team composition so as to enhance shared efficacy and performance. We often see this demonstrated with short-term teams such as task forces.

A Productive, Supportive Climate Here, we are talking about high levels of cohesiveness, mutual trust, and cooperation among team members. Sometimes these aspects are part of a team's "interpersonal climate." Team leaders contribute to this climate by role-modeling and supporting relationships that build the high levels of cohesion, trust, and collaboration. Team leaders can also work to enhance shared beliefs about team efficacy and collective capability.

Commitment to Continuous Improvement and Adaptation A successful team should be able to adapt to changing conditions. Again, both internal and external team leaders may play a role. The focus on continuous improvement may be through formal mechanisms. Often, however, teams recognize that a failure to strive for improvement actually results in a deterioration of performance.

These shared and vertical self-directing team activities tend to encourage self-leadership activities. Self-leadership can help both the individual and the team. All members, at one point or another, are expected to be leaders. Self-leadership represents a portfolio of self-influence strategies that positively influence individual behavior, thought processes, and related activities. Self-leadership activities are divided into three broad categories: behavior-focused, natural-reward, and constructive-thought-pattern strategies.[642]

Behavior-Focused Strategies Behavior-focused strategies tend to increase self-awareness, leading to the handling of behaviors involving necessary but not always pleasant tasks. These strategies include personal observation, goal setting, reward, self-correcting feedback, and practice. Self-observation involves examining your own behavior in order to increase awareness of when and why you engage in certain behaviors. Such examination identifies behaviors that should be changed, enhanced, or eliminated. Poor performance could lead to informal self-notes documenting the occurrence of unproductive behaviors. Such heightened awareness is a first step toward behavior change.

Self-Rewards It helps if you, as a team member, set high but reachable goals and provide yourself with rewards when they are reached. Self-rewards can be quite useful in moving behaviors toward goal attainment. Self-rewards can be real (e.g., a steak dinner) or imaginary (imagining a steak dinner). Also, such things as the rehearsal of desired behaviors you know will lead to self-established goals before the actual performance can prove quite useful. Rehearsals allow you to perfect skills that will be needed when the actual performance is required.

Constructive Thought Patterns Constructive thought patterns focus on the creation or alteration of cognitive thought processes. Self-analysis and improvement of belief systems, mental imagery of successful performance outcomes, and positive self-talk can help. Developing a mental image of the necessary actions allows you to think about what needs to be accomplished and how it will be accomplished before the stress of performance takes hold.

These activities can influence and control the team members' thoughts through the use of cognitive strategies designed to facilitate ways of thinking that can positively affect performance. Where these activities occur, they tend to serve as partial substitutes for hierarchical leadership even though they may be encouraged in a shared situation in contrast to a vertical leadership setting.

A final thought is in order before we move on. Leadership should not be restricted to the traditional style of vertical leadership, nor should the focus be primarily on shared leadership. Shared leadership appears in many forms and is often used successfully in combination with vertical leadership. As with a number of the leadership approaches discussed in this book, various contingencies operate that influence the emphasis that should be devoted to each of the leadership perspectives.

At some point in your career you will confront the challenge of cross-cultural leadership. This may come in the form of leading team members from different cultures or it may come when you are offered your first international assignment. Or it might happen when you are asked to join in a cooperative venture with a foreign-based supplier or distributor. There are a wide variety of approaches to meeting the challenge of cross-cultural leadership. A major research project conducted by an international team of researchers provides an excellent overview of the factors you need to consider. Called project GLOBE, it outlines the common dimensions of leadership that are important, as well as the significant differences in how effective managers lead in different cultures.

Project GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Program) is an ambitious program involving over 17,000 managers from 951 organizations functioning in 62 nations throughout the world. The project, which is led by Robert House, has involved over 140 country co-investigators, plus a coordinating team and a number of research associates.[643]

The GLOBE approach argues that leadership variables and cultural variables can be meaningfully applied at societal and organizational levels. Congruence between cultural expectations and leadership is expected to yield superior performance. The central assumption behind the model, shown in Figure 14.3, is that the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture predict organizational practices, leader attributes, and behaviors that are most often carried out and are most effective in that culture.

![A simplified version of the original GLOBE theoretical model. [Source: See Robert J. House, Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta (eds.), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004).]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1403.png)

Figure 14.3. A simplified version of the original GLOBE theoretical model. [Source: See Robert J. House, Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta (eds.), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004).]

A variety of leadership assumptions are evident in the Globe theoretical model as summarized in Figure 14.3. For example, societal cultural norms, values, and practices affect leaders' attributes and behaviors, as do organizational forms, cultures, and practices. Founders and organization members are immersed in their own societal cultures as well as in the prevailing practices in their industries. Societal cultural norms, values, and practices also affect organizational culture and practices. Both societal culture and organizational culture, in turn, influence the culturally endorsed leadership prototype. And, leader attributes and behaviors affect organizational forms, cultures, and practices.

As shown in the figure above as well, acceptance of leaders by followers facilitates leadership effectiveness. Leaders who are not accepted by organization members will find it more difficult and arduous to influence these members than leaders who are accepted. Leader effectiveness over time, furthermore, increases leader acceptance. Demonstrated leader effectiveness causes some members to adjust their behaviors toward the leader in positive ways. Those followers not accepting the leader are likely to leave the organization either voluntarily or involuntarily.

So far the GLOBE researchers have identified and studied six broad-based dimensions. That can be more or less effective in different cultures. These leadership dimensions are:

Charismatic/value-based—the extent to which the leader inspires, motivates, and expects high performance outcomes;

Team-oriented—the degree to which the leader stresses team building and implementation of a common goal among team members;

Participative—the degree to which subordinates are involved in making an implementation;

Humane-oriented—the degree to which the leader stresses support, consideration, compassion, and generosity;

Autonomous—the degree to which the leader stresses independent and individualistic leadership;

Self-protective—the degree to which the leader stresses ensuring the safety and security of the individual, self-centered, and face saving.

In addition to these leadership dimensions, the GLOBE researchers also identified and studied variations in national cultures. They chose to emphasize cultural aspects known to have some relationship to effective leadership. The presumption was that leaders in different cultures would be required to adjust their approaches to best fit these cultural differences. In other words, effective leadership is based on a good fit of leadership approach and culture. The nine dimensions of societal cultural used in the GLOBE studies are:

assertiveness: assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in relationships versus nonconfrontational;

future orientation: future-oriented behaviors such as delaying gratification and investing in the future versus a stress on immediate gratification;

gender egalitarianism: the collective minimizes gender inequality versus asserting major differences by gender;

uncertainty avoidance: reliance on social norms, rules, etc., to alleviate future unpredictability versus adaptation to rapid change;

power distance: expectation that power is equally distributed versus large differences in the power of positions and individuals;

institutional collectivism: organization/society rewards and collective resources/action versus individual rewards;

in-group collectivism: individuals express pride, loyalty, and similar attitudes in organizations/families versus individualism;

performance orientation: the collective encourages/rewards group for performance improvement versus rewards for membership;

humane orientation: the collective encourages/rewards individuals for being fair, generous, and kind.

![Summary of GLOBE comparisons for culturally endorsed leadership dimensions. [Source: Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, Mary Sully de Luque, and Robert J. House, "In the Eye of the Beholder: Cross Cultural Lessons in Leadership from Project GLOBE," Academy of Management Perspectives 20.7 (2006), pp. 67–90.] Note: H = high rank; M = medium rank; L = low rank as a culturally endorsed leadership dimension.](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1404.png)

Figure 14.4. Summary of GLOBE comparisons for culturally endorsed leadership dimensions. [Source: Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, Mary Sully de Luque, and Robert J. House, "In the Eye of the Beholder: Cross Cultural Lessons in Leadership from Project GLOBE," Academy of Management Perspectives 20.7 (2006), pp. 67–90.] Note: H = high rank; M = medium rank; L = low rank as a culturally endorsed leadership dimension.

Although each culture has its own unique pattern across these nine dimensions, nations do have enough similarities to be grouped in societal clusters. These clusters often form around geographic areas where there is a common language and an extensive pattern of interaction. For example, Argentina is a member of the Latin America societal cluster while India is a member of the Southern Asia societal cluster. Figure 14.4 shows some of the major societal clusters identified in project GLOBE and highlights a representative country for each cluster.

So far GLOBE researchers have matched cultural and leadership dimensions for over 62 countries and collapsed them to form 10 geographic clusters. For the six broad-based leadership dimensions, Figure 14.4 shows the degree to which a particular aspect of leadership is endorsed with an H for highly endorsed, an M for moderately endorsed, and an L for not endorsed. Where an emphasis on a specific leadership dimension is matched with an H on a cultural dimension, it is labeled a culturally endorsed leadership dimension. This aspect of leadership is characteristic of what individuals in the culture expect from an effective leader.

A culturally endorsed leadership dimension is one that members of a culture expect from effective leaders.

Perhaps the best way to grasp this complicated perspective is to examine the patterns across the leadership dimensions by cluster in Figure 14.4. For example, in the United States the charismatic dimension is highly endorsed while the protective dimension is not. For team orientation, endorsement is medium. In Russia, the self protective dimension is culturally endorsed. Note the differences in the degree to which specific dimensions of leadership are endorsed or refuted. For instance, there is a very sharp contrast between the Anglo cluster (of which the United States is a part) and the Middle East.

Finally, GLOBE seeks to understand which attributes of leadership are universally endorsed. To date, across the sampled countries, some aspects of leadership are associated with effective leadership while others portray ineffective leadership. Leadership described in terms of integrity, charismatic-visionary, charismatic-inspirational, and team-oriented are almost universally endorsed as indications of outstanding leadership. Leadership described in terms of irritability, egocentricity, noncooperativeness, malevolence, being a loner, dictatorial, and ruthless are identified as indicators of ineffective leadership. Some aspects of leadership were seen as effective in only some national samples and involve leaders as being characterized as individualistic, status conscious, risk taking, or self-sacrificing.

The important point to remember is that there are dramatically different expectations for leaders in different cultures. Leading across cultures is far from simple, as this overview of the GLOBE project suggests. Throughout the book we have stressed integrity, and the discussion of shared leadership emphasizes an orientation toward a team. These aspects of leadership appear to be important in most cultures. In many respects the GLOBE perspective on leadership highlights the difficulty in prescribing exactly what a leader should do in our increasingly global economy. As your career progresses and you become more engaged in cross-cultural leadership it will be important for you to go beyond a universalist view to study cultural expectations. Each culture is unique and the pattern of cultural expectations upon leaders is also unique.

There are probably as many views of strategic leadership as there are scholars studying this complex subject. When the focus is on strategic leadership it is the study of a quasi-independent unit, department, or organization. A number of researchers focus on the top management team as a group, suggesting that if there is greater diversity in the challenges and opportunities facing the firm, the top management team should be more diverse.[644] Essentially, they indicate that a major challenge of top management is to develop an effective group process that will cope with the struggles and opportunities facing the firm. Several researchers have just focused on the chief executive officer, such as a president of the United States, but new research suggests that strategic leadership is not rooted in just the top management team or the CEO.[645] It involves a number of individuals, some of whom may be partially outside the organization such as the outside members of the board of directors. To understand the challenges of strategic management it is important to examine the roles of managers at different organizational levels.

Top management teams (TMTs) refer to the relatively small group of executives at the very top of the organization or the leaders of the firm. Often the top management team is composed of three to ten executives.[646] The composition of the top management team is important because the collective nature, temperament, outlook, and interactions among these individuals alters the choices made in the leadership of the organization.

Much of the research on top management teams uses demographic characteristics as proxies for harder-to-obtain psychological variables. Such variables as age, tenure, education, and functional background are used in this perspective. Researchers typically attempt to link such variables to various kinds of organizational outcomes, including sales growth, innovation, and executive turnover.[647]

Because of conflicting findings, researchers have been working to enrich this approach. One important review argues that a given TMT is likely to face a variety of different situations over time. Demographic composition may be relatively stable but the tasks are dynamic and variable. Sometimes team members have similar information (symmetric) and interests, and sometimes not (asymmetric). With asymmetric information and symmetric interests, there is an opportunity for the top management team to develop new innovative solutions. For example, when considering a merger, some executives may have information on the potential partner's finances, its management style and strategy, or on the partner's connections with others. The team may initially move to buy the new partner but sell off selected portions of the new business.

It is important to recognize that in today's dynamic environment it is desirable for top management teams to have a variety of skills, experiences, and emergent theories which are basically explanations of what might happen and why. Diversity of the skills and abilities of the team can promote debate and discussion, which can lead to more comprehensive, balanced, and effective initiatives for improvement.[648] Homogeneous top management groups are less likely to identify and respond to subtle but important variations. This can result in stale strategies, unresponsiveness, and dulling consistency. Of course, there are practical limits to the degree of diversity and the range of emergent theories that top management can effectively discuss. Too much variation can yield excessive discussion and paralysis by analysis.[649]

The TMT researchers argue that group process must be handled differently and effectively for dynamic versus less dynamic settings. Not only should the composition of the top management team be adjusted to the degree of change facing the firm but there should also be adjustments in group process. With change facing the firm, there needs to be more emphasis on processing information, a representation of broader interests, a strong recognition of existing power asymmetries, and additional emphasis on developing new emergent theories of action.[650]

There is a variety of leadership requirements at different levels or echelons of management. The multiple-level perspective argues that there are three organizational domains from the bottom to the top of the organization, typically consisting of no more than two managerial levels within a domain: (1) the production domain at the bottom of the organization; (2) the organization domain in the middle levels; and (3) the systems domain at the top.[651] Each domain and level gets more complex than those beneath it in terms of its leadership and managerial requirements.

One way of expressing the increasing complexity of the levels is in terms of how long it takes to see the results of the key decisions required at any given domain and level. The time frame can range from three months or so at the lowest level, which emphasizes hands-on work performance and practical judgment to solve ongoing problems, to 20 years or more at the top.

Because problems become increasingly complex from the lower levels to the upper levels of the organization, you can expect that managers at each domain and level must demonstrate increasing cognitive and behavioral complexity in order to deal with an increase in organizational complexity. One way of measuring a manager's cognitive complexity is in terms of how far into the future he or she can develop a vision. Notice that this measure is trait oriented, similar in some ways but different from intelligence. In other words, using an intelligence measure instead of a complexity measure will not do. Accompanying such vision should be an increasing range and sophistication of leadership behaviors.

This approach, or extensions of it, is notable for emphasizing the impact of top leadership as it cascades deep within the organization. One example of such cascading, indirect leadership, is the leadership-at-a-distance. Even individuals several levels above a unit can influence the style and tone of what occurs in a unit. One way of thinking about such cascading is in terms of a leadership of emphasis at the top and much more of a leadership in emphasis as the cascading moves down the organization.

The systems domain leadership at the top of an organization is normally responsible for creating complex systems, organizing acquisition of major resources, creating vision, developing strategy and policy, and identifying organizational design. These functions call for a much broader conception of leadership. In many respects leadership of combines leadership and management. Of course, leadership in is also exercised in the systems and organization domains and involves a more face-to-face approach. One example of leadership of is the indirect, cascading effects of an upper-domain decision concerning, say, leadership development programs to be implemented down the organization. Another example of leadership of is the cascading of the "intent of the commander" where middle-level leaders try to mimic what they think the top-level leader would do in their situation.[652] Examine Research Insight to see how one group of researchers linked CEO values to culture and then to organizational outcomes as the values of the CEO cascaded.[653]

This multiple-level leadership view also recognizes that regardless of the level, leaders must engage in direct supervision and must be effective followers. The saying is that, "everyone has a boss." And even most CEOs would argue that those near the top must act as a team and the notion of shared leadership at the top of the organization is clearly relevant.[654]

A strategic leadership perspective developed by Boal and Hooijberg focuses on the tensions and complexity faced by strategic leaders. This perspective is shown in Figure 14.5.[655] Notice that off to the left their approach starts the notion of tension from Emergent Theories and the Competing Values Framework (CVF).[656] It suggests a tension between flexibility versus control and internal focus versus external focus. The internal versus external focus dimension distinguishes between social actions emphasizing such internal effectiveness measures as employee satisfaction, versus a focus on external effectiveness measures such as market share and profitability. The control versus flexibility dimension contrasts actions focused on goal clarity and efficiency and those emphasizing adaptation to people and the external environment. As a whole, the two focus dimensions define four quadrants and eight leadership roles that address these distinct organizational demands. They emphasize the challenges leaders often face when working toward meeting the competing demands of stakeholders.

![Boal and Hooijberg Perspective on Strategic Leadership. [Source: Kimberiy B. Boal and Robert Hooijberg, "Strategic Leadership Research: Moving On." The Leadership Quarterly 11 (2009).]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1405.png)

Figure 14.5. Boal and Hooijberg Perspective on Strategic Leadership. [Source: Kimberiy B. Boal and Robert Hooijberg, "Strategic Leadership Research: Moving On." The Leadership Quarterly 11 (2009).]

Executives who have a large repertoire of leadership roles available and know when to apply these roles are more likely to be effective than leaders who have a small role repertoire and who indiscriminately apply these roles. This repertoire and selective application is termed behavioral complexity. To exhibit both repetitive and selective application, executives need cognitive and behavioral complexity as well as flexibility. Of course, they may understand and see the differences between their subordinates and superiors but not be able to behaviorally differentiate so as to satisfy the demands of each group.

In terms of cognitive complexity, the underlying assumption is that those high in cognitive complexity process information differently and perform certain tasks better than less cognitively complex persons because they use more categories to discriminate. In other words, such complexity taps into how a person constructs meaning as opposed to what he or she thinks.

Behavioral complexity is the possession of a repertoire of leadership roles and the ability to selectively apply them.

Cognitive complexity is the underlying assumption that those high in cognitive complexity process information differently and perform certain tasks better than less cognitively complex people.

Figure 14.5 shows CVF, behavioral complexity, emotional complexity, and cognitive complexity as directly associated with absorptive capacity, capacity to change, and managerial wisdom as well as with charismatic/transformational leadership and vision. In other words, the block to the left shows the challenges and opportunities facing those at and near the top. The leadership of these individuals, alone and in combination, alter the degree to which the firm can adjust day-to-day management. As the complexity of the challenges and opportunities increase there is more stress on the organization. How it is led then becomes more important.

Organizational Competencies and Strategic Leadership Finally, consistent with the research of Boal and Hooijberg, it is important to recognize key organizational competencies and link them with strategic leadership effectiveness and ultimately with organizational effectiveness.[657] The first key competency is absorptive capacity. Absorptive capacity is the ability to learn. It involves the capacity to recognize new information, assimilate it, and apply it toward new ends. It utilizes processes necessary to improve the organization-environment fit. Absorptive capacity of strategic leaders is of particular importance because those in such a position have a unique ability to change or reinforce organizational action patterns.

Absorptive capacity is the ability to learn.

The second key competency is adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity refers to the ability to change. Boal and Hooijberg argue that in the new, fast-changing competitive landscape, organizational success calls for strategic flexibility, that is, being able to respond quickly to competitive conditions. The third key competency is managerial wisdom which involves the ability to perceive variation in the environment and understand the social actors and their relationships. Thus, emotional intelligence is called for and the leader must be able to take the right action at the right moment.

An Example of the Model Let's look at an integrative example of an engineering company that had, at one time, 100 percent of its contracts with the Department of Defense. Astute strategic leaders—those high in absorptive capacity, change, and managerial wisdom—realized that a company reorientation was necessary given the decline in the defense budget. They had to reconceptualize their organization's system. Contract bidding procedures changed; the company no longer needed to comply with numerous government regulations in I terms of its contracts, and executive leaders had to acquire new customers. These leaders tended to increase the three capacities noted above, and they formulated future visions and emphasized organizational transformation. They might even have appeared charismatic, if not visionary. Strategic leaders high in behavioral complexity and emotional intelligence are likely to spot trends more quickly than others and better prepare their organizations for the future.[658]

During the recent recession, it became quite clear that leaders are facing new and unique challenges. Not only have North American-based firms fully entered the information age, they have recognized the need to innovate or die. The old titans of the industrial age, the Fords, the GMs, the U.S. Steels, today look like remnants of a bygone era. Now we send tweets, instead of sending handwritten letters, and check e-mails on our Blackberry anytime and anywhere. Our family pictures are displayed electronically instead of as paper photos in frames or albums. Increasingly, leaders in every level of the organization are confronting the necessity and challenges of continual innovation and the uncertainty of the age. Simply put, leaders need to be acutely aware of the setting in which they lead.[659] And, the leadership needed in a routine setting is not the same leadership that is needed in other contexts.[660]

Contextual leadership perspectives detail the conditions facing the leader and then suggest the type of leadership that is needed for success. In organizational behavior, the term context is used to describe the collection of opportunities and constraints that affect the occurrence and meaning of behavior as well as the relationships among variables.[661] The different contexts may be described in terms of the stability and uncertainty facing the leader and his other unit.

Context is the collection of opportunities and constraints that affect the occurrence and meaning of behavior and the relationships among variables.

For most managers there are three major sources of instability. The first is market and environmental instability. During a recession, for example, the market is extremely unstable. Second is technological instability, where what is produced and how it is produced are changing. For example, competitors may be innovating rapidly but in ways your firm cannot easily predict. Finally, there is firm instability with an emphasis on process and procedure or internal administration instability. An example is an internal production and delivery system that needs changing but the instability is so great that the design changes cannot keep up with system demands. In other words, managers cannot clear the swamp because the alligators keep eating the workers.

Four Leadership Contexts These sources of instability can be combined to depict the overall character of the opportunities and constraints facing the leader. For simplicity consider the four contexts in Figure 14.6.[662] In context 1 (Stability), stable conditions exist and the focus is on adjusting and creating internal operations to enhance system goals. This is often the context for earlier leadership perspectives. Note that to measure success, the leader should judge progress on the basis of goals assigned to his or her unit.

![Four situational contexts, the desired leadership, and how to measure success. [Source: Based on Osborn, Hunt, and Jauch (2002).]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__1406.png)

Figure 14.6. Four situational contexts, the desired leadership, and how to measure success. [Source: Based on Osborn, Hunt, and Jauch (2002).]

In context 2 (Crisis), there are identifiable and dramatic departures from prior practice and sudden threats to high priority goals, providing little or no response time. For many managers the current recession is such a crisis and calls for dramatic action and active leadership where charismatic and transformational leadership can be particularly important. While the situation appears dire, leaders are aware of factors contributing to the crisis and can develop action plans to try and weather the storm. For example, in a recession, downsizing is a way to preserve the firm until the economy improves. To judge success, the leader should monitor the degree to which the unit is coping with the crisis and make sure it is on track to return to normal operations. While those in the middle can face a crisis, in cases of a dramatic downturn the firm may even bring in a new CEO. Examine Leaders on Leadership for the case of Carol Bartz and Yahoo.

In context 3 (Dynamic Equilibrium), organizational stability occurs only within a range of shifting priorities with programmed change efforts. This is the well-known dynamic equilibrium setting found in many analyses of corporate strategy, strategic leadership, and change leadership.

Context 4 (Near the Edge of Chaos) is a transition zone poised between order and chaos. Here, the system must rapidly adjust while maintaining sufficient stability to learn.[663] While globally operating high tech firms are classic examples of those at the edge of chaos,[664] more conventional analyses of today's corporations have suggested that many firms are moving toward the edge of chaos. Why? By moving forward with a balance of exploration and exploitation they find superior performance. Poised near the edge of chaos, firms stress innovation, responsiveness, and adaptability over routine efficiency.

Near the edge of chaos, context 4 leaders operate in uncertainty where no one person can actually describe the challenges and opportunities facing the firm. The context is just too complex. With this level of complexity some of the traditional aspects of leadership are expected to yield very poor performance. For example, transformational leadership often fails simply because no single leader is capable of charting the necessary goals and paths to keep the system viable.[665] More transactional leadership appears to provide stability but often reinforces sticking to a failed approach. The challenge is to stimulate innovation while keeping the learning environment stable.

Patterning of Attention and Network Development Recent research suggests that in order to meet context challengers, leaders need to emphasize two often neglected aspects of leadership, patterning of attention and network development.[666] Patterning of attention involves isolating and communicating important information from a potentially endless stream of events, actions, and outcome. The term patterning is used to stress the establishment of a norm where the leader is expected to ask questions, raise issues, and help gather information for unit members. The leader is not telling others what the goal is or how to reach it. Nor is the leader stressing an ideology or moral position. The leader is merely stimulating discussion among others in the setting. This discussion, in turn, produces new knowledge and information as individuals develop coping strategies.

Patterning of attention involves isolating and communicating what information is important and what is given attention from a potentially endless stream of events, actions, and outcome.

Members of a particular unit or firm may not be able to develop effective ways to compete in a very complex situation. They often need help from others and the leader may engage in network development. Network development involves developing and managing the connections among individuals both inside and outside the unit. With greater network development the leader expands the contacts needed to provide a greater diversity of information to the unit. This expansion of contacts may be with other units inside the firm or with a wide variety of knowledgeable individuals outside the firm. For instance, key customers are often consulted in order to make changes and successfully implement product innovation.

In combination, greater patterning of attention and network development increases the size, interconnectedness, and diversity of the unit to provide a variety of world views. By increasing the depth and breadth of talent in combination with increased interaction, the chances are much greater that the unit will isolate reachable goals and evolve a sustaining way of accomplishing them. Too much patterning of attention and/or network development, however, can decrease the chances of effective adaptation. This would be the case when there is too much talk and not enough action. Managers must realize that patterning of attention and network development is a delicat balancing act. Finally, as suggested in Mastering Management, network leadership can be an important aspect of influence in many contexts. In this illustration it is used to establish a philanthropic entity.[667]

Leaders can also change the situation facing them and their followers. Change leadership deals with the idea that an organization needs to master the challenges of change while creating a satisfying, healthy, and effective workplace for its employees. For over a decade firms have dealt with a "new economy (that) has ushered in great business opportunities—and great turmoil."[668] The terms "turmoil" and "turbulence" are particularly salient in the current economic environment. In addition to the traditional challenges, the forces of globalization provide a number of problems and opportunities, and the new economy is constantly springing surprises on even the most experienced organizational executives. Flexibility, competence, and commitment are the rules of the day. People in the new workplace must be comfortable dealing with adaptation and continuous change, along with greater productivity, willingness to learn from the successes of others, total quality, and continuous improvement.

To deal with all of these concerns and more, we will examine leaders as change agents, phases of planned change, change strategies, and resistance to change.

While change is the watch word for most firms it is important to separate transformational from incremental change. Some of this change may be described as radical change, or frame-breaking change.[669] This is transformational change, which results in a major overhaul of the organization or its component systems. Organizations experiencing transformational change undergo significant shifts in basic characteristics, including the overall purpose/mission, underlying values and beliefs, and supporting strategies and structures.[670] In today's business environments, transformational changes are often initiated by a critical event, such as a new CEO, a new ownership brought about by merger or takeover, or a dramatic failure in operating results. When it occurs in the life cycle of an organization, such radical change is intense and all encompassing.[671] Examine OB Savvy 14.1 to increase the chances of successfully coping with a transformational change.

The most common form of change is incremental change, or frame-bending change. This type of change, being part of an organization's natural evolution, is frequent and less traumatic than other types of change. Typical incremental changes include the introduction of new products, technologies, systems, and processes. Although the nature of the organization remains relatively the same, incremental change builds on the existing ways of operating to enhance or extend them in new directions. The capability of improving continuously through incremental change is an important asset in today's demanding business environment.

The success of both radical and incremental change in organizations depends in part on change agents who lead and support the change processes. These are individuals and groups who take responsibility for changing the existing behavior patterns of another person or even the entire social system. Although change agents are sometimes consultants hired from outside the organization, most managers in today's dynamic times are expected to act in the capacity of change agents. Indeed, this responsibility is essential to the leadership role. Simply put, being an effective change agent means being effective at "change leadership."

Planned and Unplanned Change Not all change in organizations is the result of a change agent's direction. Unplanned changes can occur spontaneously or randomly. They may be disruptive, such as a wildcat strike that ends in a plant closure, or beneficial, such as an interpersonal conflict that results in a new procedure designed to improve the flow of work between two departments. When the forces of unplanned change appear, the goal is to act quickly in order to minimize negative consequences and maximize possible benefits. In many cases, an unplanned change can be turned into an advantage.

In contrast, planned change is the result of specific efforts led by a change agent. It is a direct response to someone's perception of a performance gap—a discrepancy between the desired and actual state of affairs. Performance gaps may represent problems to be solved or opportunities to be explored. Most planned changes are efforts intended to deal with performance gaps in ways that benefit an organization and its members. The processes of continuous improvement require constant vigilance to spot performance gaps and to take action to resolve them.

Forces and Targets for Change The driving forces for change are ever-present in and around today's dynamic work settings. They are found in the organization-environment relationship, with mergers, strategic alliances, and divestitures among the examples of organizational attempts to redefine their relationships in challenging social and political environments. They are found in the organizational life cycle, with changes in culture and structure among the examples of how organizations must adapt as they evolve from birth through growth and toward maturity. They are found in the political nature of organizations, with changes in internal control structures, including benefits and reward systems that attempt to deal with shifting political currents.

Planned change is a response to someone's perception of a performance gap—a discrepancy between the desired and actual state of affairs.

Performance gap is a discrepancy between the desired and the actual conditions.

Planned change based on any of these forces can be internally directed toward a wide variety of organizational components, most of which have already been discussed in this book. As shown in Figure 14.7, these targets include organizational purpose, strategy, structure, and people, as well as objectives, culture, tasks, and technology. When considering these targets, it must be recognized that they are highly intertwined in the workplace. Changes in any one are likely to require or involve changes in others. For example, a change in the basic tasks—what people do—is inevitably accompanied by a change in technology—the way in which tasks are accomplished. Changes in tasks and technology usually require alterations in structures, including changes in the patterns of authority and communication as well as in the roles of workers. These technological and structural changes can, in turn, necessitate changes in the knowledge, skills, and behaviors of the members of the organization.[672] In all cases, tendencies to accept easy-to-implement, but questionable, "quick fixes" to problems should be avoided.

The failure rate of transformational organizational change is as high as 70 percent.[673] For a leader to improve his or her chances of success as a change agent, it is important to understand the normal process of change in organizations. Remember, most organizations operate on routines derived from prior success. Thus, a leader needs to think of any change effort in three phases—unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. All three phases must be handled well for a change to be successful.[674] Although the continuous nature of different changes means that these phases will often overlap, each phase is important and needs to be handled in a different manner. Inexperienced managers may become easily preoccupied with the changing phase and neglect the importance of the unfreezing and refreezing stages.

Unfreezing is the stage at which a situation is prepared for change. In this stage it is the responsibility of the change agent to show the need for alterations. Have environmental changes opened new opportunities? Has someone else developed a better way to get the job done? Has performance started to slip in comparison with the competition? A manager will ask such questions when he or she is preparing for improvement. Many changes are never tried, or they fail simply because situations are not properly unfrozen to begin with.

Unfreezing is the stage at which a situation is prepared for change.

Large units seem particularly susceptible to what is sometimes called the boiled frog phenomenon.[675] This refers to the notion that a live frog will immediately jump out when placed in a pan of hot water. When placed in cold water that is then heated very slowly, however, the frog will stay in the water until the water boils the frog to death. Organizations, too, can fall victim to similar circumstances. When change agents fail to monitor their environments, recognize important trends, or sense the need to change, their organizations may slowly suffer and lose their competitive edge. Although the signals that change may be needed are available, they are not noticed or given any special attention—until it is too late. In contrast, people who are always on the alert and understand the importance of "unfreezing" in the change process are the most successful leaders.

Changing involves taking action to modify a situation by altering things, such as the people, tasks, structure, or technology of the organization. Many change agents are prone to an activity trap. They bypass the unfreezing stage and start with the changing stage prematurely or too quickly. Although their intentions may be good, the situation has not been properly prepared for change and this often leads to failure. Change is difficult in any situation, let alone having to do so without setting the proper foundations.

Refreezing is the final stage in the planned change process. Designed to maintain the momentum of a change and eventually institutionalize it as part of the normal routine, refreezing secures the full benefits of long-lasting change. Refreezing involves positively reinforcing desired outcomes and providing extra support when difficulties are encountered. It involves evaluating progress and results, and assessing the costs and benefits of the change. And it allows for modifications to be made in the change to increase its success over time. If all of this is not done and refreezing is neglected, changes are often abandoned after a short time or incompletely implemented.

Changing is the stage in which specific actions are taken to create change.

Refreezing is the stage in which changes are reinforced and stabilized.

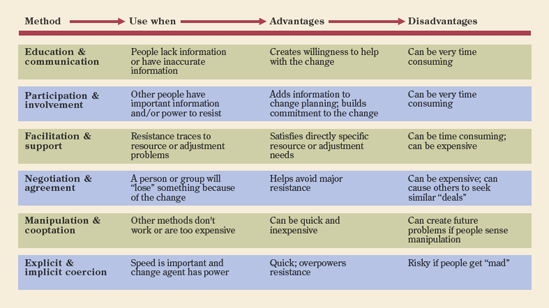

There are a variety of power change strategies utilized to mobilize power, exert influence over others, and get people to support planned change efforts. Three pure strategies, force-coercion, rational persuasion, and shared power, are described in Figure 14.8. Each of these strategies builds from the various bases of social power. Note in particular that each power source has somewhat different implications for the planned change process.[676]

Planned change strategies consist of force-coercion, rational persuasion, and shared power.

Force-Coercion A force—coercion strategy uses authority, rewards, or punishments as primary inducements to change. Here, the leader acts unilaterally to "command" change through the formal authority of his or her position, to induce change via an offer of special rewards, or to bring about change via threats of punishment. People respond to this strategy mainly out of the fear of being punished if they do not comply with a change directive or out of the desire to gain a reward if they do. Coercion compliance is usually temporary and continues only as long as the leader is present. With reliance upon legitimate authority and rewards, compliance remains as long as supervision is visible and rewards keep coming. The actions as a change agent using the force-coercion strategy might match the following profile:

Force—coercion strategy uses authority, rewards, and punishments to create change.

You believe that people who run things are motivated by self-interest and by what the situation offers in terms of potential personal gain or loss. Since you feel that people change only in response to such motives, you try to find out where their vested interests lie and then put the pressure on. If you have formal authority, you use it. If not, you resort to whatever possible rewards and punishments you have access to and do not hesitate to threaten others with these weapons. Once you find a weakness, you exploit it and are always wise to work "politically" by building supporting alliances wherever possible.[677]

Rational Persuasion Change agents using a rational persuasion strategy attempt to bring about change through the use of special knowledge, empirical support, or rational arguments. This strategy assumes that rational people will be guided by reason and self-interest in deciding whether or not to support a change. Expert power is mobilized to convince others that the change will leave them better off than before. It is sometimes referred to as an empirical-rational strategy of planned change. When successful, this strategy results in a longer-lasting, more naturalized change than does force-coercion. A change agent taking the rational persuasion approach to a change situation might behave as follows:

You believe that people are inherently rational and are guided by reason in their actions and decision making. Once a specific course of action is demonstrated to be in a person's self-interest, you assume that reason and rationality will cause the person to adopt it. Thus, you approach change with the objective of communicating—through information and facts—the essential "desirability" of change from the perspective of the person whose behavior you seek to influence. If this logic is effectively communicated, you are sure of the person who is adopting the proposed change.[678]

Shared Power A shared-power strategy actively involves the people who will be affected by a change in planning and making key decisions relating to this change. Sometimes called a normative-reeducative approach, this strategy tries to develop directions and support for change through involvement and empowerment. It builds essential foundations, such as personal values, group norms, and shared goals, so that support for a proposed change emerges naturally. Managers using normative-reeducative approaches draw on the power of personal reference and share power by allowing others to participate in planning and implementing the change. Given this high level of involvement, the strategy is likely to result in a longer-lasting and internalized change. A change agent who shares power and adopts a normative-reeducative approach to change is likely to fit this profile:

You believe that people have complex motivations and behave as they do as a result of sociocultural norms and commitments to these norms. You also recognize that changes in these orientations involve changes in attitudes, values, skills, and significant relationships, not just changes in knowledge, information, or intellectual rationales for action and practice. Thus, when seeking to change others, you are sensitive to the supporting or inhibiting effects of group pressures and norms. In working with people, you try to find out their side of things and identify their feelings and expectations [679]

In organizations, resistance to change is any attitude or behavior that indicates unwillingness to make or support a desired alteration. Leaders often view any resistance as something that must be "overcome" in order for change to be successful. This is not always the case, however. It is helpful to view resistance to change as feedback that the leader can use to facilitate gaining change objectives.[680] The essence of this constructive approach to resistance is to recognize that when people resist change, they are defending something that is important to them that appears to be threatened.

Why People Resist Change People have many reasons to resist change—fear of the unknown, insecurity, lack of a felt need to change, threat to vested interests, contrasting interpretations, and lack of resources, among other possibilities. A work team's members, for example, may resist the introduction of an advanced workstation of computers because they have never used the operating system and are apprehensive. They may wonder whether the new computers will eventually be used as justification for "getting rid" of certain members of their department, or they may believe that they have been doing their jobs just fine and do not need the new computers. These and other viewpoints often create resistance to even the best and most well-intended planned changes.

Resistance to the Change Itself Sometimes a leader experiences resistance to the change itself. People may reject a change because they believe it is not worth their time, effort, or attention. They may believe that the proposed change asks them to do more for less. To minimize resistance in such cases, the leader should make sure that everyone who may be affected by a change knows how it satisfies the following criteria.[681]

- Benefit—

The change should have a clear advantage for the people being asked to change; it should be perceived as "a better way."

- Compatibility—

The change should be as compatible as possible with the existing values and experiences of the people being asked to change.

- Complexity—

The change should be no more complex than necessary; it must be as easy as possible for people to understand and use.

- Triability—

The change should be something that people can try on a step-by-step basis and make adjustments as things progress.

Resistance to the Change Strategy Leaders must also be prepared to deal with resistance to the change strategy. Someone who attempts to bring about change via force-coercion, for example, may create resistance among individuals who resent management of leadership by "command" or the use of threatened punishment. People may resist a rational persuasion strategy in which the data are suspect or the expertise of advocates is not clear. They may resist a shared-power strategy that even appears manipulative and insincere.

Resistance to the Change Agent Resistance to a leader implementing the change often involves personality differences and a poor history of relationships. Leaders who are isolated and aloof from other persons in the change situation, who appear self-serving, or who have a high emotional involvement in the changes are especially prone to such problems. Research indicates that leaders who differ from other persons on such dimensions as age, education, and socioeconomic status may encounter greater resistance to change.[682]

How to Deal with Resistance An informed leader has many options available for dealing positively with resistance to change. Figure 14.9 summarizes insights into how and when each of these methods may be used to deal with resistance to change. Regardless of the chosen strategy, it is always best to remember that the presence of resistance typically suggests that something can be done to achieve a better fit among the change, the situation, and the people affected. A good leader deals with resistance to change by listening to feedback and acting accordingly.[683]

The first approach in dealing with resistance to change is through education and communication. The objective is to teach people about a change before it is implemented and to help them understand the logic of the change. Education and communication seem to work best when resistance is based on inaccurate or incomplete information. A second way is the use of participation and involvement. With the goal of allowing others to help design and implement the changes, this approach asks people to contribute ideas and advice or to work on task forces or committees that may be leading the change. This is useful when the leader does not have all the information needed to successfully handle a problem situation. Here, for instance, the increased use of patterning of attention and network development by the leader may help resolve tensions.

Facilitation and support help to deal with resistance by providing help—both emotional and material—for people experiencing the hardships of change. Here a leader increases consideration by actively listening to problems and complaints. This is matched with greater initiating structure where the leader provides training in the new ways, and helps others to overcome performance pressures. Facilitation and support are highly recommended when people are frustrated by work constraints and difficulties encountered in the change process.

A negotiation and agreement approach offers incentives to actual or potential change resistors. Trade-offs are arranged to provide special benefits in exchange for assurances that the change will not be blocked. It is most useful when dealing with a person or group that will lose something of value as a result of the planned change.

Frustrated managers may attempt to use manipulation and co-optation in covert attempts to influence others, selectively providing information and consciously structuring events so that the desired change occurs. While manipulation and co-optation are common when other tactics do not work, only the more astute and experience executives find they can gain temporary reductions in resistance.

In a crisis, some leaders find that in order to overcome resistance to change they must resort to explicit or implicit coercion. Often, resistors are threatened with a variety of undesirable consequences if they do not go along with the plan. In a crisis, the temporary compliance to the change may be all that is necessary to weather the storm. Unfortunately, crises are much rarer than the use of this approach. When the crisis is past, even the temporary use of coercion means that leaders will need to embark on a new change program that stresses facilitation and support.

Finally, it is important to recognize the history, change, and culture of the firm as it undergoes planned change. Often a planned change will yield unanticipated alterations in the culture of the organization. We will spend the next chapter delving into the concept of organizational culture and the necessity to promote innovation, a unique kind of planned change.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 14.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 14 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What is moral leadership?

Moral leadership includes authentic leadership, servant leadership, and spiritual and ethical leadership.

Authentic leadership emphasizes owning one's personal experiences and acting in accordance with one's true or core self which underlies virtually all other aspects of leadership.

Servant leadership is where the leader is attuned to basic spiritual values and, in serving these, serves others including colleagues, the organization, and society.

Spiritual leadership is a field of inquiry within the broader setting of workplace spirituality; it includes values, attitudes, and behaviors required to intrinsically motivate self and others to have a sense of spiritual survival through calling and membership.

Ethical leadership emphasizes moral concerns.

What is shared leadership?

Shared leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both.

The influence process often involves peer or lateral influence and at other times involves upward or downward hierarchical influence within a team.

Although broader than traditional vertical leadership, shared leadership may be used in combination with it.

Self-leadership techniques can be used to improve the effectiveness of shared leadership.

How do you lead across cultures?

Cross-cultural leadership emphasizes Project GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Effectiveness Research Program), which involves 62 societies, 951 organizations, and about 140 country co-investigators.

It assumes that the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture predict organizational practices and leader attributes and behaviors that are most often carried out and most effective in that culture.

It identifies a number of potentially important aspects of culture that form the basis for culturally based leader prototypes.

It matches key aspects of leadership to the important aspects of culture to identify endorsed elements of leadership.

It suggests both universally endorsed elements of leadership as well as those unique to a particular culture and group of nations.

What is strategic leadership?

When the focus is on strategic leadership this is leadership of a quasi-independent unit, department, or organization.

The expectations for leaders, the time frame for their actions, and the complexity of the assignments increases as one moves up the organizational hierarchy.

Strategic leadership, as used here, includes the leadership of both the CEO and the top management team.

Boal and Hooijberg's view of strategic leadership uses emergent theories: cognitive complexity, emotional intelligence (complexity), and behavioral complexity as well as charismatic, transformational, and visionary leadership to influence absorptive capacity, capacity to change, and managerial wisdom, which in turn influence effectiveness.