1. Learning Styles

Activity | Suggested Part | Overview |

|---|---|---|

1. Learning Styles Inventory—Online at: | 1 | This online inventory provides insight into a person's relative strengths on seven alternative approaches to learning, described as: visual learner, print learner, auditory learner, interactive learner, haptic learner, kinesthetic learner, and olfactory learner. |

2. Study Tips for Different Learning Styles | 1 | This reading included in the workbook provides study tips for learners with different tendencies and strengths. |

2. Student Leadership Practices Inventory by Kouzes and Posner

Activity | Suggested Part | Overview |

|---|---|---|

1. Student Leadership Practices Inventory—Student Workbook | All | This workbook includes a worksheet to help interpret feedback and plan improvement in each leadership practice assessed, sections on how to compare scores with the normative sample and how to share feedback with constituents, and more than 140 actual steps students can take to get results. |

2. Student Leadership Practices Inventory—Self | All | This 30-item inventory will help students evaluate their performance and effectiveness as a leader. Results from the simple scoring process help students prepare plans for personal leadership development. |

3. Student Leadership Practices Inventory—Observer | All | This version of the LPI is used by others to assess the individual's leadership tendencies, thus allowing for comparison with self-perceptions. |

See companion Web site for online versions of many assessments: www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Assessment | Suggested Chapter | Cross-References and Integration |

|---|---|---|

1. Managerial Assumptions | 1 Organizational Behavior Today | leadership |

2. A Twenty-First-Century Manager | 1 Organizational Behavior Today 14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change 16 Organizational Goals and Structures 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | leadership; decision making; globalization |

3. Turbulence Tolerance Test | 1 Organizational Behavior Today 2 Individual Differences, Values, and Diversity | perception; individual differences; organizational change and stress |

4. Global Readiness Index | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction 14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change | diversity; culture; leading; perception; management skills; career readiness |

5. Personal Values | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction 6 Motivation and Performance | perception; diversity and individual differences; leadership |

6. Intolerance for Ambiguity | 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning | perception; leadership |

7. Two-Factor Profile | 5 Motivation Theories 6 Motivation and Performance | job design; perception; culture; human resource management |

8. Are You Cosmopolitan? | 6 Motivation and Performance 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | diversity and individual differences; organizational culture |

9. Group Effectiveness | 7 Teams in Organizations 8 Teamwork and Team Performance 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | organizational designs and cultures; leadership |

10. Least Preferred Co-worker Scale | 13 Foundations for Leadership | diversity and individual differences; perception; group dynamics and teamwork |

11. Leadership Style | 13 Foundations for Leadership | diversity and individual differences; perception; group dynamics and teamwork |

12. "TT" Leadership Style | 11 Communication and Collaboration 13 Foundations for Leadership | diversity and individual differences; perception; group dynamics and teamwork |

13. Empowering Others | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance 11 Communication and Collaboration 12 Power and Politics | leadership; perception and attribution |

14. Machiavellianism | 12 Power and Politics | leadership; diversity and individual differences |

15. Personal Power Profile | 12 Power and Politics | leadership; diversity and individual differences |

16. Your Intuitive Ability | 9 Creativity and Decision Making | diversity and individual differences |

17. Decision-Making Biases | 7 Teams in Organizations 9 Creativity and Decision Making | teams and teamwork; communication; perception |

18. Conflict Management Strategies | 10 Conflict and Negotiation | diversity and individual differences; communication |

19. Your Personality Type | 2 Individual Differences, Values, and Diversity | diversity and individual differences; job design |

20. Time Management Profile | 2 Individual Differences, Values, and Diversity | diversity and individual differences |

21. Organizational Design Preference | 16 Organizational Goals and Structures 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | job design; diversity and individual differences |

22. Which Culture Fits You? | 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | perception; diversity and individual differences |

Selections from The Pfeiffer Annual Training

Activity | Suggested Part | Overview |

|---|---|---|

A. Sweet Tooth: Bonding Strangers into a Team | Parts 1, 3, 4 | Perception, teamwork, decision making, communication |

B. Interrogatories: Identifying Issues and Needs | Parts 1, 3, 4 | Current issues, group dynamics, communication |

C. Decode: Working with Different Instructions | Parts 3, 4 | Decision making, leadership, conflict, teamwork |

D. Choices: Learning Effective Conflict Management Strategies | Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Conflict, negotiation, communication, decision making |

E. Internal/External Motivators: Encouraging Creativity | Parts 2, 4, 5 | Creativity, motivation, job design, decision making |

F. Quick Hitter: Fostering the Creative Spirit | Parts 4, 5 | Creativity, decision making, communication |

Additional Team and Experiential Exercises

Exercise | Suggested Chapter | Cross-References and Integration |

|---|---|---|

1. My Best Manager | 1 Introducing Organizational Behavior 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction | leadership |

2. Graffiti Needs Assessment | 1 Introducing Organizational Behavior | human resource management; communication |

3. My Best Job | 1 Introducing Organizational Behavior 6 Motivation and Performance | motivation; job design; organizational cultures |

4. What Do You Value in Work? | 5 Motivation Theories | diversity and individual differences; performance management and rewards; motivation; job design; decision making |

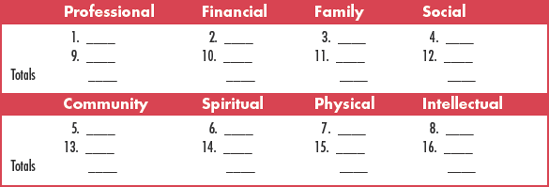

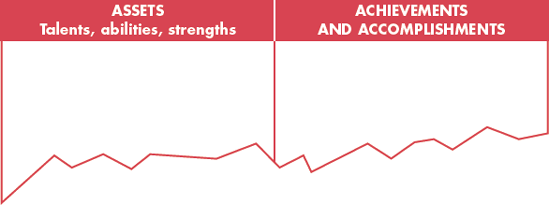

5. My Asset Base | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning | perception and attribution; diversity and individual differences; groups and teamwork; decision making |

6. Expatriate Assignments | 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | perception and attribution; diversity and individual differences; decision making |

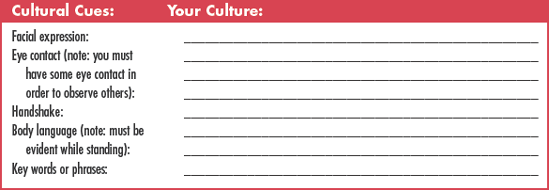

7. Cultural Cues | 14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change | perception and attribution; diversity and individual differences; decision making; communication; conflict; groups and teamwork |

8. Prejudice in Our Lives | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction | perception and attribution; decision making; conflict; groups and teamwork |

9. How We View Differences | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | culture; international; diversity and individual differences; decision making; communication; conflict; groups and teamwork |

10. Alligator River Story | 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning | diversity and individual differences; decision making; communication; conflict; groups and teamwork |

11. Teamwork and Motivation | 5 Motivation Theories | performance management and rewards; groups and teamwork |

12. The Downside of Punishment | 5 Motivation Theories | motivation; perception and attribution; performance management and rewards |

13. Tinkertoys | 6 Motivation and Performance 16 Organizational Goals and Structures 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | organizational structure; design and culture; groups and teamwork |

14. Job Design Preferences | 6 Motivation and Performance | motivation; job design; organizational design; change |

15. My Fantasy Job | 6 Motivation and Performance | motivation; individual differences; organizational design; change |

16. Motivation by Job Enrichment | 6 Motivation and Performance | motivation; job design; perception; diversity and individual differences; change |

17. Annual Pay Raises | 5 Motivation Theories 6 Motivation and Performance | motivation; learning and reinforcement; perception and attribution; decision making; groups and teamwork |

18. Serving on the Boundary | 7 Teams in Organizations | intergroup dynamics; group dynamics; roles; communication; conflict; stress |

19. Eggsperiential Exercise | 7 Teams in Organizations | group dynamics and teamwork; diversity and individual differences; communication |

20. Scavenger Hunt—Team Building | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance | groups; leadership; diversity and individual differences; communication; leadership |

21. Work Team Dynamics | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance | groups; motivation; decision making; conflict; communication |

22. Identifying Team Norms | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance | groups; communication; perception and attribution |

23. Workgroup Culture | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | groups; communication; perception and attribution; job design; organizational culture |

24. The Hot Seat | 8 Teamwork and Team Performance | groups; communication; conflict and negotiation; power and politics |

25. Interview a Leader | 12 Power and Politics 13 Foundations for Leadership | performance management and rewards; groups and teamwork; new workplace; organizational change and stress |

26. Leadership Skills Inventories | 13 Foundations for Leadership | individual differences; perception and attribution; decision making |

27. Leadership and Participation in Decision Making | 13 Foundations for Leadership | decision making; communication; motivation; groups; teamwork |

28. My Best Manager. Revisited | 12 Power and Politics | diversity and individual differences; perception and attribution |

29. Active Listening | 11 Communication and Collaboration | group dynamics and teamwork; perception and attribution |

30. Upward Appraisal | 6 Motivation and Performance 11 Communication and Collaboration | perception and attribution; performance management and rewards |

31. 360° Feedback | 6 Motivation and Performance 11 Communication and Collaboration | communication; perception and attribution; performance management and rewards |

32. Role Analysis Negotiation | 9 Creativity and Decision Making | communication; group dynamics and teamwork; perception and attribution; communication; decision making |

33. Lost at Sea | 9 Creativity and Decision Making | communication; group dynamics and teamwork; conflict and negotiation |

34. Entering the Unknown | 9 Creativity and Decision Making 10 Conflict and Negotiation | communication; group dynamics and teamwork; perception and attribution |

35. Vacation Puzzle | 10 Conflict and Negotiation | conflict and negotiation; communication; power; leadership |

36. The Ugli Orange | 9 Creativity and Decision Making 10 Conflict and Negotiation | communication; decision making |

37. Conflict Dialogues | 10 Conflict and Negotiation | conflict; communication; feedback; perception; stress |

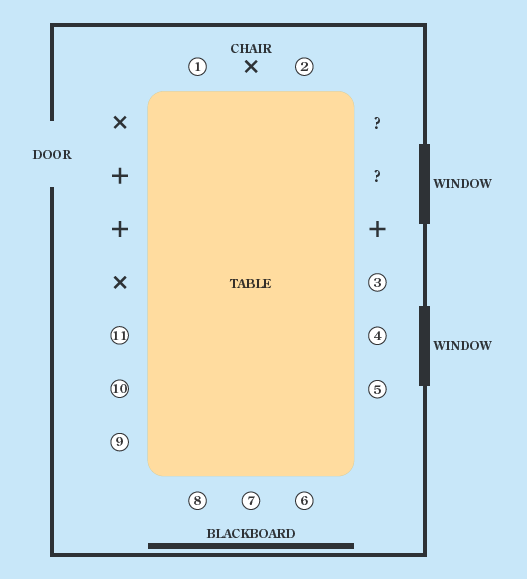

38. Force-Field Analysis | 9 Creativity and Decision Making | decision making; organization structures, designs, cultures |

39. Organizations Alive! | 16 Organizational Goals and Structures 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | organizational design and culture; performance management and rewards |

40. Fast-Food Technology | 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation 16 Organizational Goals and Structures | organizational design; organizational culture; job design |

41. Alien Invasion | 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation 16 Organizational Goals and Structures 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | organizational structure and design; international; diversity and individual differences; perception and attribution |

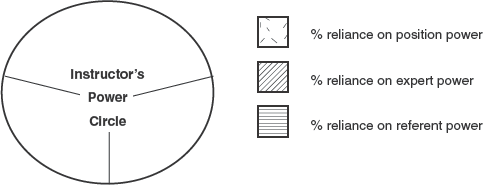

42. Power Circles Exercise | 12 Power and Politics | influence; power; leadership; change management |

Case | Suggested Chapter | Cross-References and Integration |

|---|---|---|

1a. Trader Joe's | 1 Introducing Organizational Behavior | human resource management; organizational cultures; innovation; information technology; leadership |

1b. Management Training Dilemma | 1 Introducing Organizational Behavior | ethics and decision making; communication; conflict and negotiation |

2. Ursula Burns, Xerox | 2 Individual Differences, Values, and Diversity | diversity and individual differences; perception and attribution; performance management; job design; communication; conflict; decision making |

3. Louise Quam, Tysvar, LLC | 3 Emotions, Attitudes, and Job Satisfaction | organizational cultures; globalization; innovation; motivation |

4. MagRec, Inc. | 4 Perception, Attribution, and Learning | ethics and diversity; organizational structure, design, and culture; decision making; organizational change |

5. It Isn't Fair | 5 Motivation Theories | perception and attribution; performance management and rewards; communication; ethics and decision making |

6a. Perfect Pizzeria | 6 Motivation and Performance | organizational design; motivation; performance management and rewards |

6b. Hovey and Beard | 6 Motivation and Performance | organizational cultures; globalization; communication; decision making |

7. The Forgotten Group Member | 7 Teams in Organizations | teamwork; motivation; diversity and individual differences; perception and attribution; performance management and rewards; communication; conflict; leadership |

8. NASCAR's Racing Teams | 7 Teams in Organizations | organizational cultures; leadership; motivation and reinforcement; communication |

9. Decisions, Decisions | 9 Creativity and Decision Making | organizational structure; organizational cultures; change and innovation; group dynamics and teamwork; diversity and individual differences |

10. The Missing Raise | 10 Conflict and Negotiation | change; innovation and stress; job designs; communication; power and politics |

11. The Poorly Informed Walrus | 11 Communication and Collaboration | diversity and individual differences; perception and attribution |

12. Faculty Empowerment | 12 Power and Politics | change; innovation and stress; job designs; communication; power and politics |

13a. The New Vice President | 13 Foundations for Leadership | leadership; performance management and rewards; diversity and individual differences; communication; conflict and negotiation; power and influence |

13b. Southwest Airlines | 14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change | leadership; performance management and rewards; diversity and individual differences; communication; conflict and negotiation; power and influence |

14. Novo Nordisk | 14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change | leadership; performance management and rewards; diversity and individual differences; communication; conflict and negotiation; power and influence |

15. Never on a Sunday | 15 Organizational Culture and Innovation | ethics and diversity; organizational structure, design, and culture; decision making; organizational change |

16. First Community Financial | 16 Organizational Goals and Structures | organizational structure, designs, and culture; performance management and rewards |

17. Mission Management and Trust | 17 Strategy, Technology, and Organizational Design | organizational structure, designs, and culture; performance management and rewards |

This is a Wiley resource—www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Step 1.

Take the Learning Style Instrument at www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Step 2.

The instrument will give you scores on seven learning styles:

Visual learner—focus on visual depictions such as pictures and graphs

Print learner—focus on seeing written words

Auditory learner—focus on listening and hearing

Interactive learner—focus on conversation and verbalization

Haptic learner—focus on sense of touch or grasp

Kinesthetic learner—focus on physical involvement

Olfactory learner—focus on smell and taste

Step 3.

Consider your top four rankings among the learning styles. They suggest your most preferred methods of learning.

Step 4.

Read the following study tips for the learning styles. Think about how you can take best advantage of your preferred learning styles.

Have you ever repeated something to yourself over and over to help remember it? Or does your best friend ask you to draw a map to someplace where the two of you are planning to meet, rather than just tell her the directions? If so, then you already have an intuitive sense that people learn in different ways. Researchers in learning theory have developed various categories of learning styles. Some people, for example, learn best by reading or writing. Others learn best by using various senses—seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, or even smelling. When you understand how you learn best, you can make use of learning strategies that will optimize the time you spend studying. To find out what your particular learning style is, go to www.wiley.com/college/boone and take the learning styles quiz you find there. The quiz will help you determine your primary learning style:

Visual Learner | Auditory Learner | Haptic Learner | Olfactory Learner |

Print Learner | Interactive Learner | Kinesthetic Learner |

Then, consult the information below and on the following pages for study tips for each learning style. This information will help you better understand your learning style and how to apply it to the study of business.

Study Tips for Visual Learners

If you are a Visual Learner, you prefer to work with images and diagrams. It is important that you see information.

Visual Learning

Draw charts/diagrams during lecture.

Examine textbook figures and graphs.

Look at images and videos on WileyPLUS and other Web sites.

Pay close attention to charts, drawings, and handouts your instructor uses.

Underline; use different colors.

Use symbols, flowcharts, graphs, different arrangements on the page, white spaces.

Visual Reinforcement

Make flashcards by drawing tables/charts on one side and definition or description on the other side.

Use art-based worksheets; cover labels on images in text and then rewrite the labels.

Use colored pencils/markers and colored paper to organize information into types.

Convert your lecture notes into "page pictures." To do this:

Use the visual learning strategies outlined above.

Reconstruct images in different ways.

Redraw pages from memory.

Replace words with symbols and initials.

Draw diagrams where appropriate.

Practice turning your visuals back into words.

If visual learning is your weakness: If you are not a Visual Learner but want to improve your visual learning, try re-keying tables/charts from the textbook.

Study Tips for Print Learners

If you are a Print Learner, reading will be important but writing will be much more important.

Print Learning

Write text lecture notes during lecture.

Read relevant topics in textbook, especially textbook tables.

Look at text descriptions in animations and Web sites.

Use lists and headings.

Use dictionaries, glossaries, and definitions.

Read handouts, textbooks, and supplementary library readings.

Use lecture notes.

Print Reinforcement

Rewrite your notes from class, and copy classroom handouts in your own handwriting.

Make your own flashcards.

Write out essays summarizing lecture notes or text book topics.

Develop mnemonics.

Identify word relationships.

Create tables with information extracted from textbook or lecture notes.

Use text-based worksheets or crossword puzzles.

Write out words again and again.

Reread notes silently.

Rewrite ideas and principles into other words.

Turn charts, diagrams, and other illustrations into statements.

Practice writing exam answers.

Practice with multiple choice questions.

Write paragraphs, especially beginnings and endings.

Write your lists in outline form.

Arrange your words into hierarchies and points.

If print learning is your weakness: If you are not a Print Learner but want to improve your print learning, try covering labels of figures from the textbook and writing in the labels.

Study Tips for Auditory Learners

If you are an Auditory Learner, then you prefer listening as a way to learn information. Hearing will be very important, and sound helps you focus.

Auditory Learning

Make audio recordings during lecture. Do not skip class; hearing the lecture is essential to understanding.

Play audio files provided by instructor and textbook.

Listen to narration of animations.

Attend lecture and tutorials.

Discuss topics with students and instructors.

Explain new ideas to other people.

Leave spaces in your lecture notes for later recall.

Describe overheads, pictures, and visuals to somebody who was not in class.

Auditory Reinforcement

Record yourself reading the notes and listen to the recording.

Write out transcripts of the audio files.

Summarize information that you have read, speaking out loud.

Use a recorder to create self-tests.

Compose "songs" about information.

Play music during studying to help focus.

Expand your notes by talking with others and with information from your textbook.

Read summarized notes out loud.

Explain your notes to another auditory learner.

Talk with the instructor.

Spend time in quiet places recalling the ideas.

Say your answers out loud.

If auditory learning is your weakness: If you are not an Auditory Learner but want to improve your auditory learning, try writing out the scripts from pre-recorded lectures.

Study Tips for Interactive Learners

If you are an Interactive Learner, you will want to share your information. A study group will be important.

Interactive Learning

Ask a lot of questions during lecture or TA review sessions.

Contact other students, via e-mail or discussion forums, and ask them to explain what they learned.

Interactive Reinforcement

"Teach" the content to a group of other students.

Talking to an empty room may seem odd, but it will be effective for you.

Discuss information with others, making sure that you both ask and answer questions.

Work in small group discussions, making a verbal and written discussion of what others say.

If interactive learning is your weakness: If you are not an Interactive Learner but want to improve your interactive learning, try asking your study partner questions and then repeating them to the instructor.

Study Tips for Haptic Learners

If you are a Haptic Learner, you prefer to work with your hands. It is important to physically manipulate material.

Haptic Learning

Take blank paper to lecture to draw charts/tables/diagrams.

Using the textbook, run your fingers along the figures and graphs to get a "feel" for shapes and relationships.

Haptic Reinforcement

Trace words and pictures on flash-cards.

Perform electronic exercises that involve drag-and-drop activities.

Alternate between speaking and writing information.

Observe someone performing a task that you would like to learn.

Make sure you have freedom of movement while studying.

If haptic learning is your weakness: If you are not a Haptic Learner but-want to improve your haptic learning, try spending more time in class working with graphs and tables while speaking or writing down information.

Study Tips for Kinesthetic Learners

If you are a Kinesthetic Learner, it will be important that you involve your body during studying.

Kinesthetic Learning

Ask permission to get up and move during lecture.

Participate in role-playing activities in the classroom.

Use all your senses.

Go to labs; take field trips.

Listen to real-life examples.

Pay attention to applications.

Use trial-and-error methods.

Use hands-on approaches.

Kinesthetic Reinforcement

Make flashcards; place them on the floor, and move your body around them.

Move while you are teaching the material to others.

Put examples in your summaries.

Use case studies and applications to help with principles and abstract concepts.

Talk about your notes with another Kinesthetic person.

Use pictures and photographs that illustrate an idea.

Write practice answers.

Role-play the exam situation.

If kinesthetic learning is your weakness: If you are not a Kinesthetic Learner but want to improve your kinesthetic learning, try moving flashcards to reconstruct graphs and tables, etc.

Study Tips for Olfactory Learners

If you are an Olfactory Learner, you will prefer to use the senses of smell and taste to reinforce learning. This is a rare learning modality.

Olfactory Learning

During lecture, use different scented markers to identify different types of information.

Olfactory Reinforcement

Rewrite notes with scented markers.

If possible, go back to the computer lab to do your studying.

Burn aromatic candles while studying.

Try to associate the material that you're studying with a pleasant taste or smell.

If olfactory learning is your weakness: If you are not an Olfactory Learner but want to improve your olfactory learning, try burning an aromatic candle or incense while you study, or eating cookies during study sessions.

James M. Kouzes

Barry Z. Posner, Ph.D.

Jossey-Bass Publishers • San Francisco

Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer Classroom Collection

Copyright © 1998 by James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0-7879-4425-4

Jossey-Bass is a registered trademark of Jossey-Bass Inc., a Wiley Company.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ. 07030-5774, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. [email protected].

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly, call (888) 378-2537, fax to (800) 605-2665, or visit our Web site at www.josseybass.com.

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Jossey-Bass books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department at Jossey-Bass.

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

This book is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

"Leadership is everyone's business." That's the conclusion we have come I to after nearly two decades of research into the behaviors and actions of people who are making a difference in their organizations, clubs, k teams, classes, schools, campuses, communities, and even their families. We found that leadership is an observable, learnable set of practices. Contrary to some myths, it is not a mystical and ethereal process that cannot be understood by ordinary people. Given the opportunity for feedback and practice, those with the desire and persistence to lead—to make a difference—can substantially improve their ability to do so.

The Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) is part of an extensive research project into the everyday actions and behaviors of people, at all levels and across a variety of settings, as they are leading. Through our research we identified five practices that are common to all leadership experiences. In collaboration with others, we extended our findings to student leaders and to school and college environments and created the student version of the LPI.[1] The LPI is a tool, not a test, designed to assess your current leadership skills. It will identify your areas of strength as well as areas of leadership that need to be further developed.

The Student LPI helps you discover the extent to which you (in your role as a leader of a student group or organization) engage in the following five leadership practices:

Challenging the Process. Leaders are pioneers—people who seek out new opportunities and are willing to change the status quo. They innovate, experiment, and explore ways to improve the organization. They treat mistakes as learning experiences. Leaders also stay prepared to meet whatever challenges may confront them. Challenging the Process involves

Searching for opportunities

Experimenting and taking risks

As an example of Challenging the Process, one student related how innovative thinking helped him win a student class election: "I challenged the process in more than one way. First, I wanted people to understand that elections are not necessarily popularity contests, so I campaigned on the issues and did not promise things that could not possibly be done. Second, I challenged the incumbent positions. They thought they would win easily because they were incumbents, but I showed them that no one has an inherent right to a position."

Challenging the Process for a student serving as treasurer of her sorority meant examining and abandoning some of her leadership beliefs: "I used to believe, 'If you want to do something right, do it yourself.' I found out the hard way that this is impossible to do.... One day I was ready to just give up the position because I could no longer handle all of the work. My adviser noticed that I was overwhelmed, and she turned to me and said three magic words: 'Use your committee.' The best piece of advice I would pass along about being an effective leader is that it is okay to experiment with letting others do the work."

Inspiring a Shared Vision.

Leaders look toward and beyond the horizon. They envision the future with a positive and hopeful outlook. Leaders are expressive and attract other people to their organization and teams through their genuineness. They communicate and show others how their interests can be met through commitment to a common purpose. Inspiring a Shared Vision involves

Envisioning an uplifting future

Enlisting others in a common vision

Describing his experience as president of his high school class, one student wrote: "It was our vision to get the class united and to be able to win the spirit trophy.... I told my officers that we could do anything we set our minds on. Believe in yourself and believe in your ability to accomplish things."

Enabling Others to Act. Leaders infuse people with energy and confidence, developing relationships based on mutual trust. They stress collaborative goals. They actively involve others in planning, giving them discretion to make their own decisions. Leaders ensure that people feel strong and capable. Enabling Others to Act involves

Fostering collaboration

Strengthening people

It is not necessary to be in a traditional leadership position to put these principles into practice. Here is an example from a student who led his team as a team member, not from a traditional position of power: "I helped my team members feel strong and capable by encouraging everyone to practice with the same amount of intensity that they played games with. Our practices improved throughout the year, and by the end of the year had reached the point I was striving for: complete involvement among all players, helping each other to perform at our very best during practice times."

Modeling the Way. Leaders are clear about their personal values and beliefs. They keep people and projects on course by behaving consistently with these values and modeling how they expect others to act. Leaders also plan projects and break them down into achievable steps, creating opportunities for small wins. By focusing on key priorities, they make it easier for others to achieve goals. Modeling the Way involves

Setting the example

Achieving small wins

Working in a business environment taught one student the importance of Modeling the Way. She writes: "I proved I was serious because I was the first one on the job and the last one to leave. I came prepared to work and make the tools available to my crew. I worked alongside them and in no way portrayed an attitude of superiority. Instead, we were in this together."

Encouraging the Heart. Leaders encourage people to persist in their efforts by linking recognition with accomplishments and visibly recognizing contributions to the common vision. They express pride in the achievements of the group or organization, letting others know that their efforts are appreciated. Leaders also find ways to celebrate milestones. They nurture a team spirit, which enables people to sustain continued efforts. Encouraging the Heart involves

Recognizing individual contributions

Celebrating team accomplishments

While organizing and running a day camp, one student recognized volunteers and celebrated accomplishments through her actions. She explains: "We had a pizza party with the children on the last day of the day camp. Later, the volunteers were sent thank you notes and 'valuable volunteer awards' personally signed by the day campers. The pizza party, thank you notes, and awards served to encourage the hearts of the volunteers in the hopes that they might return for next year's day camp."

But some things can be changed only if there is a strong and genuine inner desire to make a difference. For example, enthusiasm for a cause is unlikely to be developed through education or job assignments; it must come from within.

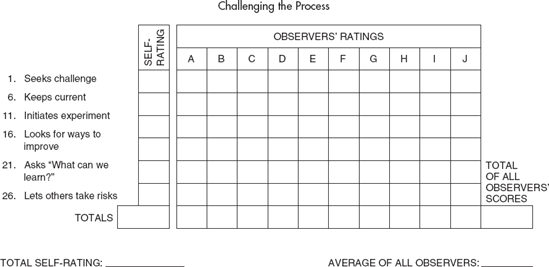

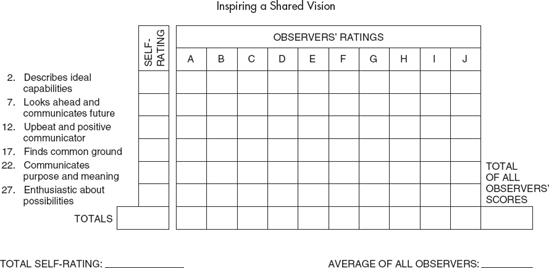

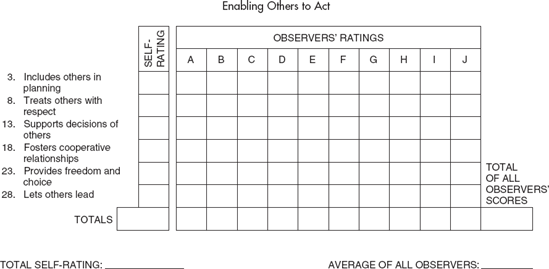

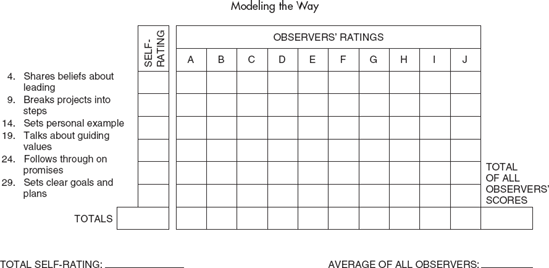

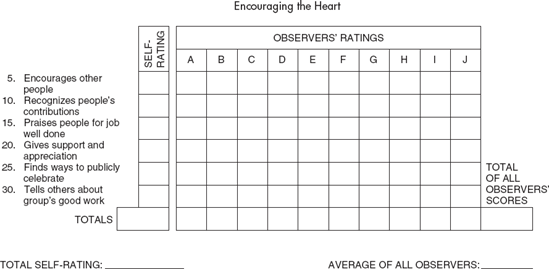

On pages W-18 through W-21 are grids for recording your Student LPI scores. The first grid (Challenging the Process) is for recording scores for items 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, and 26 from the Student LPI-Self and Student LPI-Observer. These are the items that relate to behaviors involved in Challenging the Process, such as searching for opportunities, experimenting, and taking risks. An abbreviated form of each item is printed beside the grid as a handy reference.

In the first column, which is headed "Self-Rating," write the scores that you gave yourself. If others were asked to complete the Student LPI-Observer and if the forms were returned to you, enter their scores in the columns (A, B, C, D, E, and so on) under the heading "Observers' Ratings." Simply transfer the numbers from page W-18 of each Student LPI-Observer to your scoring grids, using one column for each observer. For example, enter the first observer's scores in column A, the second observer's scores in column B, and so on. The grids provide space for the scores of as many as ten observers.

After all scores have been entered for Challenging the Process, total each column in the row marked "Totals." Then add all of the totals for observers; do not include the "self" total. Write this grand total in the space marked "Total of All Observers' Scores." To obtain the average, divide the grand total by the number of people who completed the Student LPI-Observer. Write this average in the blank provided. The sample grid shows how the grid would look with scores for self and five observers entered.

The other four grids should be completed in the same manner.

The second grid (Inspiring a Shared Vision) is for recording scores to the items that pertain to envisioning the future and enlisting the support of others. These include items 2, 7, 12, 17, 22, and 27.

The third grid (Enabling Others to Act) pertains to items 3, 8, 13, 18, 23, and 28, which involve fostering collaboration and strengthening others.

The fourth grid (Modeling the Way) pertains to items about setting an example and planning small wins.

These include items 4, 9, 14, 19, 24, and 29.

The fifth grid (Encouraging the Heart) pertains to items about recognizing contributions and celebrating accomplishments. These are items 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30.

Grids for Recording Student LPI Scores

Scores should be recorded on the following grids in accordance with the instructions on page W-17. As you look at individual scores, remember the rating system that was used:

"1" means that you rarely or seldom engage in the behavior.

"2" means that you engage in the behavior once in a while.

"3" means that you sometimes engage in the behavior.

"4" means that you engage in the behavior fairly often.

"5" means that you engage in the behavior very frequently.

After you have recorded all of your scores and calculated the totals and averages, turn to page W-21 and read the section on interpreting scores.

This section will help you to interpret your scores by looking at them in several ways and by making notes to yourself about what you can do to become a more effective leader.

Ranking Your Ratings

Refer to the previous chapter, "Recording Your Scores." On each grid, look at your scores in the blanks marked "Total Self-Rating." Each of these totals represents your responses to six statements about one of the five leadership practices. Each of your totals can range from a low of 6 to a high of 30.

In the blanks that follow, write "1" to the left of the leadership prac tice with the highest total self-rating, "2" by the next-highest total self-rating, and so on. This ranking represents the leadership practices with which you feel most comfortable, second-most comfortable, and so on. The practice you identify with a "5" is the practice with which you feel least comfortable.

Again refer to the previous chapter, but this time look at your scores in the blanks marked "Average of All Observers." The number in each blank is the average score given to you by the people you asked to complete the Student LPI-Observer. Like each of your total self-ratings, this number can range from 6 to 30.

In the blanks that follow, write "1" to the right of the leadership practice with the highest score, "2" by the next-highest score, and so on. This ranking represents the leadership practices that others feel you use most often, second-most often, and so on.

Self | Observers | |

_____ | Challenging the Process | _____ |

_____ | Inspiring a Shared Vision | _____ |

_____ | Enabling Others to Act | _____ |

_____ | Modeling the Way | _____ |

_____ | Encouraging the Heart | _____ |

Comparing Your Self-Ratings to Observers' Ratings

To compare your Student LPI-Self and Student LPI-Observer assessments, refer to the "Chart for Graphing Your Scores" on the next page. On the chart, designate your scores on the five leadership practices (Challenging, Inspiring, Enabling, Modeling, and Encouraging) by marking each of these points with a capital "S" (for "Self"). Connect the five resulting "S scores" with a solid line and label the end of this line "Self" (see sample chart below).

If other people provided input through the Student LPI-Observer, designate the average observer scores (see the blanks labeled "Average of All Observers" on the scoring grids) by marking each of the points with a capital "O" (for "Observer"). Then connect the five resulting "O scores" with a dashed line and label the end of this line "Observer" (see sample chart). Completing this process will provide you with a graphic representation (one solid and one dashed line) illustrating the relationship between your self-perception and the observations of other people.

Percentile Scores

Look again at the "Chart for Graphing Your Scores." The column to the far left represents the Student LPI-Self percentile rankings for more than 1,200 student leaders. A percentile ranking is determined by the percentage of people who score at or below a given number. For example, if your total self-rating for "Challenging" is at the 60th percentile line on the "Chart for Graphing Your Scores," this means that you assessed yourself higher than 60 percent of all people who have completed the Student LPI; you would be in the top 40 percent in this leadership practice. Studies indicate that a "high" score is one at or above the 70th percentile, a "low" score is one at or below the 30th percentile, and a score that falls between those ranges is considered "moderate."

Using these criteria, circle the "H" (for "High"), the "M" (for "Moderate"), or the "L" (for "Low") for each leadership practice on the "Range of Scores" table below. Compared to other student leaders around the country, where do your leadership practices tend to fall? (Given a "normal distribution," it is expected that most people's scores will fall within the moderate range.)

Range of Scores

In my perception | In others' perception | ||||||

Practice | Rating | Practice | Rating | ||||

Challenging the Process | H | M | L | Challenging the Process | H | M | L |

Inspiring a Shared Vision | H | M | L | Inspiring a Shared Vision | H | M | L |

Enabling Others to Act | H | M | L | Enabling Others to Act | H | M | L |

Modeling the Way | H | M | L | Modeling the Way | H | M | L |

Encouraging the Heart | H | M | L | Encouraging the Heart | H | M | L |

Exploring Specific Leadership Behaviors

Looking at your scoring grids, review each of the thirty items on the Student LPI by practice. One or two of the six behaviors within each leadership practice may be higher or lower than the rest. If so, on which specific items is there variation? What do these differences suggest? On which specific items is there agreement? Please write your thoughts in the following space.

Challenging the Process

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Inspiring a Shared Vision

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Enabling Others to Act

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Modeling the Way

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Encouraging the Heart

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Comparing Observers' Responses to One Another

Study the Student LPI-Observer scores for each of the five leadership practices. Do some respondents' scores differ significantly from others? If so, are the differences localized in the scores of one or two people? On which leadership practices do the respondents agree? On which practices do they disagree? If you try to behave basically the same with all the people who assessed you, how do you explain the difference in ratings? Please write your thoughts in the following space.

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Take a few moments to summarize your Student LPI feedback by completing the following Strengths and Opportunities Summary Worksheet. Refer to the "Chart for Graphing Your Scores," the "Range of Scores" table, and any notes you have made.

After the summary worksheet you will find some suggestions for getting started on meeting the leadership challenge. With these suggestions in mind, review your Student LPI feedback and decide on the actions you will take to become an even more effective leader. Then complete the Action-Planning Worksheet to spell out the steps you will take. (One Action-Planning Worksheet is included in this workbook, but you may want to develop action plans for several practices or behaviors. You can make copies of the blank form before you fill it in or just use a separate sheet of paper for each leadership practice you plan to improve.)

Strengths and Opportunities Summary Worksheet

Strengths

Which of the leadership practices and behaviors are you most comfortable with? Why? Can you do more?

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Areas for Improvement

What can you do to use a practice more frequently? What will it take to feel more comfortable?

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

The following are ten suggestions for getting started on meeting the leadership challenge.

Prescriptions for Meeting the Leadership Challenge

Challenge the Process

Fix something

Adopt the "great ideas" of others

Inspire a Shared Vision

Let others know how you feel

Recount your "personal best"

Enable Others to Act

Always say "we"

Make heroes of other people

Model the Way

Lead by example

Create opportunities for small wins

Encourage the Heart

Write "thank you" notes

Celebrate, and link your celebrations to your organization's values

Action-Planning Worksheet

What would you like to be better able to do?

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

What specific actions will you take?

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

What is the first action you will take? Who will be involved? When will you begin?

Action __________________________

________________________________

________________________________

People Involved ________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

Target Date ________________

Complete this sentence: "I will know I have improved in this leadership skill when ..."

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

When will you review your progress?_______________________

James M. Kouzes is chairman of TPG/Learning Systems, which makes leadership work through practical, performance-oriented learning programs. In 1993 The Wall Street Journal cited Jim as one of the twelve most requested "nonuniversity executive-education providers" to U.S. companies. His list of past and present clients includes AT&T, Boeing, Boy Scouts of America, Charles Schwab, Ciba-Geigy, Dell Computer, First Bank System, Honeywell, Johnson & Johnson, Levi Strauss & Co., Motorola, Pacific Bell, Stanford University, Xerox Corporation, and the YMCA

Barry Z. Posner, PhD, is dean of the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University, and professor of organizational behavior. He has received several outstanding teaching and leadership awards, has published more than eighty research and practitioner-oriented articles, and currently is on the editorial review boards for The Journal of Management Education, The Journal of Management Inquiry, and The Journal of Business Ethics. Barry also serves on the board of directors for Public Allies and for The Center for Excellence in Non-Profits. His clients have ranged from retailers to firms in health care, high technology, financial services, manufacturing, and community service agencies.

Kouzes and Posner are coauthors of several best-selling and award-winning leadership books. The Leadership Challenge: How to Keep Getting Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations (2nd ed., 1995), with over 800,000 copies in print, has been reprinted in fifteen languages, has been featured in three video programs, and received a Critic's Choice award from the nation's newspaper book review editors. Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It, Why People Demand It (1993) was chosen by Industry Week as one of the five best management books of the year. Their latest book is Encouraging the Heart: A Leader's Guide to Rewarding and Recognizing Others (1998).

Transferring the Scores

After you have responded to the thirty statements on the previous two pages, please transfer your responses to the blanks below. This will make it easier to record and score your responses. Notice that the numbers of the statements are listed horizontally. Make sure that the number you assigned to each statement is transferred to the appropriate blank. Fill in a response for every item.

1. _____ | 2. _____ | 3. _____ | 4. _____ | 5. _____ |

6. _____ | 7. _____ | 8. _____ | 9. _____ | 10. _____ |

11. _____ | 12. _____ | 13. _____ | 14. _____ | 15. _____ |

16. _____ | 17. _____ | 18. _____ | 19. _____ | 20. _____ |

21. _____ | 22. _____ | 23. _____ | 24. _____ | 25. _____ |

26. _____ | 27. _____ | 28. _____ | 29. _____ | 30. _____ |

Further Instructions

Please write your name here:__________________________________________

Please bring this form with you to the workshop (seminar or class) or return this form to:

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

If you are interested in feedback from other people, ask them to complete the Student LPI-Observer, which provides you with perspectives on your leadership behaviors as perceived by others.

Jossey-Bass is a registered trademark of Jossey-Bass Inc., a Wiley Company.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ, 07030-5774, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008.

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass Publishers

350 Sansome Street

San Francisco, California 94104

(888) 378-2537

Fax (800) 605-2665

www.josseybass.com

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

This instrument is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

ISBN: 0-7879-4426-2

Transferring the Scores

After you have responded to the thirty statements on the previous two pages, please transfer your responses to the blanks below. This will make it easier to record and score your responses. Notice that the numbers of the statements are listed horizontally. Make sure that the number you assigned to each statement is transferred to the appropriate blank. Fill in a response for every item.

1. _____ | 2. _____ | 3. _____ | 4. _____ | 5. _____ |

6. _____ | 7. _____ | 8. _____ | 9. _____ | 10. _____ |

11. _____ | 12. _____ | 13. _____ | 14. _____ | 15. _____ |

16. _____ | 17. _____ | 18. _____ | 19. _____ | 20. _____ |

21. _____ | 22. _____ | 23. _____ | 24. _____ | 25. _____ |

26. _____ | 27. _____ | 28. _____ | 29. _____ | 30. _____ |

Further Instructions

The above scores are for (name of person):_______________________________

Please bring this form with you to the workshop (seminar or class) or return this form to:

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

ISBN: 0-7879-4427-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass Publishers

350 Sansome Street

San Francisco, California 94104

(888) 378-2537

Fax (800) 605-2665

www.josseybass.com

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This instrument is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

Find online versions of many assessments at www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Procedure:

The general idea is just to relax, have fun, and get to know one another while completing a task. Form groups of five. All groups in the room will be competing to see which one can first complete the following items with the name of a candy bar or sweet treat. The team that completes the most items correctly first will win a prize.

Source: Robert Allan Black, The 2002 Annual Volume 1, Training/© 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Pee Wee ..., baseball player.

Dried up cows.

Kids' game minus toes.

Not bad and more than some.

Explosion in the sky.

Polka....

Rhymes with Bert's, dirts, hurts.

Happy place to drink.

Drowning prevention device.

Belongs to a mechanic from Mayberry's cousin.

They're not "lesses"; they're....

Two names for a purring pet.

Takes 114 licks to get to the center of these.

Sounds like asteroids.

A military weapon.

A young flavoring.

Top of mountains in winter.

To catch fish you need to....

Sounds like riddles and fiddles.

Questions for discussion:

What lessons about effective teamwork can be learned from this activity?

What caused each subgroup to be successful?

What might be learned about effective teamwork from what happened during this activity?

What might be done next time to increase the chances of success?

Variation

Have the individual subgroups create their own lists of clues for the names of candies/candy bars/sweets. Collect the lists and make a grand list using one or two from each group's contribution. Then hold a competition among the total group.

Procedure:

This activity is an opportunity to discover what issues and questions people have brought to the class. The instructor will select from the topic list below. Once a topic is raised, participants should ask any questions they have related to that topic. No one is to answer a question at this time. The goal is to come up with as many questions as possible in the time allowed. Feel free to build on a question already asked, or to share a completely different question.

Questions for discussion:

How did you feel about this process?

What common themes did you hear?

What questions would you most like to have answered?

Interrogatories Starter Topic List

Class requirements

Coaching

Communication

Customers

Instant messaging

Job demands

Leadership

Management

Meetings

Mission

Performance appraisal

Personality

Priorities

Project priorities

Quality

Rules

Service

Social activities

Success

Task uncertainty

Teamwork

Time

Training

Values

Work styles

Source: Cher Holton, The 2002 Annual: Volume 1, Training/© 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Procedure:

You are probably familiar with codes and cryptograms from your childhood days. In a cryptogram, each letter in the message is replaced by another letter of the alphabet. For example, LET THE GAMES BEGIN! May become this cryptogram:

YZF FOZ JUKZH CZJVQ!

In the cryptogram Y replaces L, Z replaces E, F replaces T, and so on. Notice that the same letter substitutions are used throughout this cryptogram: Every E in the sentence is replaced by a Z, and every T is replaced by an F.

Here's some information to help you solve cryptograms:

Letter Frequency

The most commonly used letters of the English language are e, t, a, i, o, n, s, h, and r.

The letters that are most commonly found at the beginning of words are t, a, o, d, and w.

The letters that are most commonly found at the end of words are e, s, d, and t.

Word Frequency

One-letter words are either a or I.

The most common two-letter words are to, of, in, it, is, as, at, be, we, he, so, on, an, or, do, if, up, by, and my.

The most common three-letter words are the, and, are, for, not, but, had, has, was, all, any, one, man, out, you, his, her, and can.

The most common four-letter words are that, with, have, this, will, your, from, they, want, been, good, much, some, and very.

The goal of the activity is to learn to work together more effectively in teams. Form into groups of four to seven members each. Have members briefly share their knowledge of solving cryptogram puzzles.

In this exercise all groups will be asked to solve the same cryptogram. If a team correctly and completely solves the cryptogram within two minutes, it will earn two hundred points. If it takes more than two minutes but fewer than three minutes, the team will earn fifty points.

Before working on the cryptogram, each participant will receive an Instruction Sheet with hints on how to solve cryptograms. Participants can study this sheet for two minutes only. They may not mark up the Instruction Sheet but they may take notes on an index card or a blank piece of paper. The Instruction Sheets will be taken back after two minutes.

At any time a group can send one of its members to ask for help from the instructor. The instructor will decode any one of the words in the cryptogram selected by the group member.

After the points are tallied, the instructor will lead class discussion.

Decode Cryptogram

ISV'B JZZXYH BPJB BPH SVQE

_____________________________

UJE BS UCV CZ BS FSYTHBH.

_____________________________

ZSYHBCYHZ BPH AHZB UJE BS

_____________________________

UCV CZ BS FSSTHWJBH UCBP

_____________________________

SBPHWZ—Z. BPCJMJWJOJV

_____________________________

Source: Sivasailam "Thiagi" Thiagarajan, The 2003 Annual: Volume 1, Training/© 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Procedure: Form teams of three.

Assume you are a group of top managers who are responsible for an organization of seven departments. Working as a team, choose an appropriate strategy to intervene in the situations below when the conflict must be managed in some way. Your choices are withdrawal, suppression, integration, compromise, and authority. Refer to the list below for some characteristics of each strategy. Write your team's choice following each situation number. Engage in discussion led by the instructor.

CHOICES: STRATEGIES AND CONTINGENCIES

Withdrawal Strategy

Use When (Advantages)

Choosing sides is to be avoided

Critical information is missing

The issue is outside the group

Others are competent and delegation is appropriate

You are powerless

Be Aware (Disadvantages)

Legitimate action ceases

Direct information stops

Failure can be perceived

Cannot be used in a crisis

Suppression (and Diffusion) Strategy

Use When (Advantages)

A cooling down period is needed

The issue is unimportant

A relationship is important

Be Aware (Disadvantages)

The issue may intensify

You may appear weak and ineffective

Integration Strategy

Use When (Advantages)

Group problem solving is needed

New alternatives are helpful

Group commitment is required

Promoting openness and trust

Be Aware (Disadvantages)

Group goals must be put first

More time is required for dialogue

It doesn't work with rigid, dull people

Compromise Strategy

Use When (Advantages)

Power is equal

Resources are limited

A win-win settlement is desired

Be Aware (Disadvantages)

Action (a third choice) can be weakened

Inflation is encouraged

A third party may be needed for negotiation

Authority Strategy

Use When (Advantages)

A deadlock persists

Others are incompetent

Time is limited (crisis)

An unpopular decision must be made

Survival of the organization is critical

Be Aware (Disadvantages)

Emotions intensify quickly

Dependency is promoted

Winners and losers are created

Source: Chuck Kormanski, Sr., and Chuck Kormanski, Jr., The 2003 Annual: Volume 1, Training/© 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Situation #1

Two employees of the support staff have requested the same two-week vacation period. They are the only two trained to carry out an essential task using a complex computer software program that cannot be mastered quickly. You have encouraged others to learn this process so there is more backup for the position, but heavy workloads have prevented this from occurring.

Situation #2

A sales manager has requested a raise because there are now two salespeople on commission earning higher salaries. The work performance of this individual currently does not merit a raise of the amount requested, mostly due to the person turning in critical reports late and missing a number of days of work. The person's sales group is one of the highest rated in the organization, but this may be the result of having superior individuals assigned to the team, rather than to the effectiveness of the manager.

Situation #3

It has become obvious that the copy machine located in a customer service area is being used for a variety of personal purposes, including reproducing obscene jokes. A few copies have sometimes been found lying on or near the machine at the close of the business day. You have mentioned the matter briefly in the organization's employee newsletter, but recently you have noticed an increase in the activity. Most of the office staff seems to be involved.

Situation #4

Three complaints have filtered upward to you from long-term employees concerning a newly hired individual. This person has a pierced nose and a visible tattoo. The work performance of the individual is adequate and the person does not have to see customers; however, the employees who have complained allege that the professional appearance of the office area has been compromised.

Situation #5

The organization has a flex-time schedule format that requires all employees to work the core hours of 10 A.M. to 3 P.M., Monday through Friday. Two department managers have complained that another department does not always maintain that policy. The manager of the department in question has responded by citing recent layoffs and additional work responsibilities as reasons for making exceptions to policy.

Situation #6

As a result of a recent downsizing, an office in a coveted location is now available. Three individuals have made a request to the department manager for the office. The manager has recommended that the office be given to one of the three. This individual has the highest performance rating, but was aided in obtaining employment with the company by the department manager, who is a good friend of the person's family. Colleagues prefer not to work with this individual, as there is seldom any evidence of teamwork.

Situation #7

Two department managers have requested a budget increase in the areas of travel and computer equipment. Each asks that your group support this request. The CEO, not your group, will make the final decision. You are aware that increasing funds for one department will result in a decrease for others, as the total budget figures for all of these categories are set.

Situation #8

Few of the management staff attended the Fourth of July picnic held at a department manager's country home last year. This particular manager, who has been a loyal team player for the past twenty-one years, has indicated that he/she plans to host the event again this year. Many of you have personally found the event to be boring, with little to do but talk and eat. Already a few of the other managers have suggested that the event be held at a different location with a new format or else be cancelled.

Situation #9

It has come to your attention that a manager and a subordinate in the same department are having a romantic affair openly in the building. Both are married to other people. They have been taking extended lunch periods, yet both remain beyond quitting time to complete their work. Colleagues have begun to complain that neither is readily available mid-day and that they do not return messages in a timely manner.

Situation #10

Two loyal department managers are concerned that a newly hired manager who is wheelchair-bound has been given too much in the way of accommodations beyond what is required by the Americans with Disabilities Act. They have requested similar changes to make their own work lives easier. Specifically, they cite office size and location on the building's main floor as points of contention.

Procedure:

This interactive, experience-based activity is designed to increase participants' awareness of creativity and creative processes. Begin by thinking of a job that you now hold or have held. Then complete Questions 1 and 2 from the Internal/External Motivators Questionnaire (see below).

Form into groups. Share your questionnaire results and make a list of responses to Question 1.

Discuss and compare rankings of major work activities listed for Question 2. Make a list with at least two responses from each participant.

Individually record your answers to Questions 3 and 4 below. Then share your answers and again list member responses within your group.

Individually, compare your responses to Questions 1 and 2 with your responses to Questions 3 and 4. Then answer Question 5. Again, share with the group and make a group list of answers to Question 5 for the recorder, who is to record these answers on the flip chart. (Ten minutes.)

Questions for Discussion:

What was the most important part of this activity for you?

What have you learned about motivation?

What impact will having done this activity have for you back in the workplace?

How will what you have learned change your leadership style or future participation in a group?

What will you do differently based on what you have learned?

INTRINSIC/EXTRINSIC MOTIVATORS QUESTIONNAIRE

How could you do your job in a more creative manner? List some ways in the space below:

List four or five major work activities or jobs you perform on a regular basis in the left-hand boxes on the following chart. Use a seven-point scale that ranges from 1 (low) to 7 (high) to rate each work activity on three separate dimensions: (a) level of difficulty, (b) potential to motivate you, and (c) opportunity to add value to the organization.

Major Work Activity

Level of Difficulty

Potential to Motivate

Opportunity to Add Value

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

List five motivators or types of rewards that would encourage you to do your job in a more creative manner.

List three motivators or types of rewards from Question 3 above that you believe would definitely increase your creativity. Indicate whether these motivators are realistic or unrealistic in terms of your job or work setting. Indicate whether each is intrinsic or extrinsic.

Motivators

Realistic/Unrealistic

Intrinsic

Extrinsic

1.

2.

3.

List three types of work activities you like to perform and the motivators or rewards that would stimulate and reinforce your creativity.

Work Activity

Rewards That Reinforce Creativity

1.

2.

3.

Source: Elizabeth A. Smith, The 2003 Annual: Volume 1, Training/© 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Part A Procedure:

Write the Roman numeral nine (IX) on a sheet of paper.

Add one line to make six. After you have one response, try for others.

Questions for discussion:

What does solving this puzzle show us about seeing things differently?

Why don't some people consider alternatives easily?

What skills or behaviors would be useful for us to develop our ability to see different points of view?

Part B Procedure:

Rent the video or DVD of "Patch Adams." In this video Patch (Robin Williams) is studying to become a doctor, but he does not look, act, or think like a traditional doctor. For Patch, humor is the best medicine. He is always willing to do unusual things to make his patients laugh. Scenes from this video can be revealing to an OB class.

Show the first Patch Adams scene (five minutes)—this is in the psychiatric hospital where Patch has admitted himself after a failed suicide attempt. He meets Arthur in the hospital. Arthur is obsessed with showing people four fingers of his hand and asking them: "How many fingers can you see?" Everybody says four. The scene shows Patch visiting Arthur to find out the solution. Arthur's answer is: "If you only focus on the problem, you will never see the solution. Look further. You have to see what other people do not see."

Engage the class in discussion of these questions and more:

How does this film clip relate to Part A of this exercise?

What restricts our abilities to look beyond what we see?

How can we achieve the goal of seeing what others do not see?

Show the second Patch Adams scene (five minutes)—this is when Patch has left the hospital and is studying medicine. Patch and his new friend Truman are having breakfast. Truman is reflecting on the human mind and on the changing of behavioral patterns (the adoption of programmed answers) as a person grows older. Patch proposes to carry out the Hello Experiment. The objective of the experiment is "to change the programmed answer by changing the usual parameters."

Engage the class in discussion of these questions and more:

What is a programmed answer?

What is the link between our programmed answers and our abilities to exhibit creativity?

How can we "deprogram" ourselves?

Summarize the session with a wrap-up discussion of creativity, including barriers and ways to encourage it.

Source: Mila Gascó Hernández and Teresa Torres Coronas, The 2003 Annual: Volume 1, Training/© 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

While vacationing in the Caribbean, founder "Trader" Joe Coulombe, discovered a way to differentiate his 7-Eleven-style corner stores from those of his competitors. Joe observed that consumers are more likely to try new things while on vacation. With a nautical theme and cheerful guides sporting Hawaiian shirts, Joe transformed his stores into oases of value by replacing humdrum sundries with exotic, one-of-a-kind foods priced persuasively below any reasonable competitor.[4]

For over fifty years, Trader Joe's has competed with such giants as Whole Foods and Dean & DeLuca. So what is its recipe for success? The company applies its pursuit of value to every facet of its operations. Buyers travel all over the world in search of great tasting foods and beverages. By focusing on natural ingredients, inspiring flavors, and buying direct from the producer whenever possible, Trader Joes' is able to keep costs down. The chain prides itself on its thriftiness and cost-saving measures, proclaiming, "We run a pretty lean ship," "Every penny we save is a penny you save," and "Our CEO doesn't even have a secretary."[5]

"When you look at food retailers," says Richard George, professor of food marketing at St. Joseph's University, "there is the low end, the big middle, and then there is the cool edge—that's Trader Joe's."[6] But how does Trader Joe's compare with other stores with an edge, such as Whole Foods? Both obtain products locally and from all over the world. Each values employees and strives to offer the highest quality. However, there's no mistaking that Trader Joe's is cozy and intimate, whereas Whole Foods' spacious stores offer an abundance of choices. By limiting its stock and selling quality products at low prices, Trader Joe's sells twice as much per square foot than other supermarkets.[7] Most retail mega-markets, such as Whole Foods, carry between 25,000 and 45,000 products; Trader Joe's stores carry only 1,500 to 2,000.[8] But this scarcity benefits both Trader Joe's and its customers. According to Swarthmore professor Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice: Why Less Is More, "Giving people too much choice can result in paralysis.... [Rjesearch shows that the more options you offer, the less likely people are to choose any."[9]

Despite the lighthearted tone suggested by marketing materials and in-store ads, Trader Joe's aggressively courts friendly, customer-oriented employees by writing job descriptions highlighting desired soft skills ("ambitious and adventurous, enjoy smiling and have a strong sense of values") as much as actual retail experience.[10]

Trader Joe's connects with its customers because of the culture of product knowledge and customer involvement that its management cultivates among store employees. Trader Joe's considers its responsible, knowledgeable, and friendly "crew" to be critical to its success. Therefore they nurture their employees with a promote-from-within philosophy.

Each employee is encouraged to taste and learn about the products and to engage customers to share what they've experienced. Most shoppers recall instances when helpful crew members took the time to locate or recommend particular items. Says one employee,

"Our customers don't just come here to buy a loaf of bread. They can do that anywhere. They come to try new things. They come to see a friendly face. They come because they know our names and we know theirs. But most of all, they come because we can tell them why not all Alaskan salmon has to come from Alaska or the difference between a Shiraz and a Syrah. The flow of ideas and information at the store level is always invigorating."[11]

When it comes to showing its appreciation for its employees, Trader Joe's puts its money where its mouth is. Those who work for Trader Joe's earn considerably more than their counterparts at other chain grocers. Starting benefits include medical, dental, and vision insurance, company-paid retirement, paid vacation, and a 10% employee discount.[12] Being a privately owned company and a little media shy, Trader Joe's has been keeping some of its financial information confidential these days, but would say that managers make in the neighborhood of $100K per year.

Outlet managers are highly compensated, substantially more so than at other retailers, partly because they know the Trader Joe's system inside and out (managers are hired only from within the company). Future leaders enroll in training programs such as Trader Joe's University that foster in them the loyalty necessary to run stores according to both company and customer expectations, teaching managers to imbue their part-timers with the customer-focused attitude shoppers have come to expect.[13]