chapter at a glance

The recognition of individual differences is central to any discussion of organizational behavior. This chapter addresses the nature of individual differences and describes why understanding and valuing these differences is increasingly important in today's workplace. Here's what to look for in Chapter 2. When finished reading, check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT ARE INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND WHY ARE THEY IMPORTANT?

Self-Awareness and Awareness of Others

Components of Self

Development of Self

WHAT IS PERSONALITY?

Big Five Personality Traits

Social Traits

Personal Conception Traits

Emotional Adjustment Traits

HOW ARE PERSONALITY AND STRESS RELATED?

Sources of Stress

Outcomes of Stress

Managing Stress

WHAT ARE INDIVIDUAL VALUES?

Sources of Values

Types of Values

Values across National Cultures

WHY IS DIVERSITY IMPORTANT IN THE WORKPLACE?

Importance of Diversity

Types of Diversity

Valuing and Supporting Diversity

In 1999, when Xerox was making a succession decision, everyone was surprised to see Anne Mulcahy, a relative newcomer, selected as CEO. Dubbed the "accidental CEO" because she never aspired to the job, she quickly acted to recruit the best talent she could find. A key player turned out to be Ursula Burns. Like Mulcahy, Burns was an unusual choice. Raised in a housing project on Manhattan's Lower East Side by a hard-working single mother who cleaned, ironed, and provided child care in order to give her daughter a private education and the opportunity to earn an engineering degree from Columbia University, Burns was not your typical executive. Together, Mulcahy and Burns are breaking new ground. In 2007, marking the first time a woman CEO of a Fortune 500 company turned over the reins to another woman, Mulcahy selected Burns to be president and to be seated on the Board of Directors.

"I think we are really tough on each other ...in a way most people couldn't handle."

Mulcahy was Burns's role model as she rose through the Xerox ranks. Burns remembers being on a panel with Mulcahy and realizing, "Wow, this woman is exactly where I am going." Mulcahy coaches Burns, shooting her looks in meetings when Burns needs to listen instead of "letting my big mouth drive the discussion," says Burns with a laugh. Mulcahy is pushing Burns to develop a poker face, telling her after a meeting, "Ursula, they could read your face. You have to be careful. Sometimes it's not appropriate."

Mulcahy and Burns show how individual differences can build a strong team. Their relationship is complex and sometimes contentious: "I think we are really tough on each other," says Mulcahy. "We are in a way most people can't handle. Ursula will tell me when she thinks I am so far away from the right answer." Chimes in Burns: "I try to be nice."[103]

appreciating that people are different

People are complex. While you approach a situation one way, someone else may approach it quite differently. These differences among people can make the ability to predict and understand behavior in organizations challenging. They also contribute to what makes the study of organizational behavior so fascinating.

In OB, the term individual differences is used to refer to the ways in which people are similar and how they vary in their thinking, feeling, and behavior. Although no two people are completely alike, they are also not completely different. Therefore, the study of individual differences attempts to identify where behavioral tendencies are similar and where they are different. The idea is that if we can figure out how to categorize behavioral tendencies and identify which tendencies people have, we will be able to more accurately predict how and why people behave as they do.

Although individual differences can sometimes make working together effectively difficult, they can also offer great benefits. The best teams often result from combining people with different skills and approaches and who think in different ways—by putting the "whole brain" to work.[104] For people to capitalize on these differences requires understanding and valuing what differences are and what benefits they can offer.

In this chapter we examine factors that increase awareness of individual differences—our own and others—in the workplace. Two factors that are important for this are self-awareness and awareness of others. Self-awareness means being aware of our own behaviors, preferences, styles, biases, personalities, etc., and awareness of others means being aware of these same things in others. To help engage this awareness, we begin by understanding components of the self and how these components are developed. We then discuss what personality is and identify the personality characteristics and values that have the most relevance for OB. As you read these concepts, think about where you fall on them. Do they sound like you? Do they sound like people you know?

Collectively, the ways in which an individual integrates and organizes personality and the traits they contain make up the components of the self, or the self-concept. The self-concept is the view individuals have of themselves as physical, social, and spiritual or moral beings.[105] It is a way of recognizing oneself as a distinct human being.

A person's self-concept is greatly influenced by his or her culture. For example, Americans tend to disclose much more about themselves than do the English; that is, an American's self-concept is more assertive and talkative.[106]

Two related—and crucial—aspects of the self-concept are self-esteem and self-efficacy. Self-esteem is a belief about one's own worth based on an overall self-evaluation.[107] People high in self-esteem see themselves as capable, worthwhile, and acceptable and tend to have few doubts about themselves. The opposite is true of a person low in self-esteem. Some OB research suggests that whereas high self-esteem generally can boost performance and satisfaction outcomes, when under pressure, people with high self-esteem may become boastful and act egotistically. They may also be overconfident at times and fail to obtain important information.[108]

Self-efficacy, sometimes called the "effectance motive," is a more specific version of self-esteem. It is an individual's belief about the likelihood of successfully completing a specific task. You could have high self-esteem yet have a feeling of low self-efficacy about performing a certain task, such as public speaking.

Self-efficacy is an individual's belief about the likelihood of successfully completing a specific task.

Just what determines the development of the self? Is our personality inherited or genetically determined, or is it formed by experience? You may have heard someone say something like, "She acts like her mother." Similarly, someone may argue that "Bobby is the way he is because of the way he was raised." These two arguments illustrate the nature/nurture controversy: Are we the way we are because of heredity—that is, genetic endowment—or because of the environments in which we have been raised and live—cultural, social, situational? As shown, these two forces actually operate in combination. Heredity consists of those factors that are determined at conception, including physical characteristics, gender, and personality factors. Environment consists of cultural, social, and situational factors.

The impact of heredity on personality continues to be the source of considerable debate. Perhaps the most general conclusion we can draw is that heredity sets the limits on just how much personality characteristics can be developed; environment determines development within these limits. For instance, a person could be born with a tendency toward authoritarianism, and that tendency could be reinforced in an authoritarian work environment. These limits appear to vary from one characteristic to the next, and across all characteristics there is about a 50–50 heredity-environment split.[109]

A person's development of the self is also related to his or her culture. As we show throughout this book, cultural values and norms play a substantial role in the development of an individual's personality and behaviors. Contrast the individualism of U.S. culture with the collectivism of Mexican culture, for example.[110] Social factors reflect such things as family life, religion, and the many kinds of formal and informal groups in which people participate throughout their lives—friendship groups, athletic groups, and formal workgroups. Finally, the demands of differing situational factors emphasize or constrain different aspects of an individual's personality. For example, in class are you likely to rein in your high spirits and other related behaviors encouraged by your personality? On the other hand, at a sporting event, do you jump up, cheer, and loudly criticize the referees?

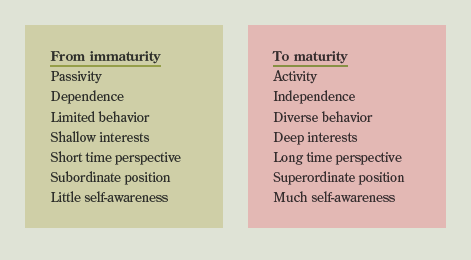

The developmental approaches of Chris Argyris, Daniel Levinson, and Gail Sheehy systematically examine the ways personality develops across time. Argyris notes that people develop along a continuum of dimensions from immaturity to maturity, as shown in Figure 2.1. He believes that many organizations treat mature adults as if they were still immature and that this creates many problems in terms of bringing out the best in employees. Levinson and Sheehy maintain that an individual's personality unfolds in a series of stages across time. Sheehy's model, for example, talks about three stages—ages 18–30, 30–45, and 45–85 +. Each of these has a crucial impact on the worker's employment and career, as we will discuss in Chapter 3. The implications are that personalities develop over time and require different managerial responses. Thus, the needs and other personality aspects of people initially entering an organization change sharply as they move through different stages or toward increased maturity.[111]

The term personality encompasses the overall combination of characteristics that capture the unique nature of a person as that person reacts to and interacts with others. As an example, think of a person who in his senior year in high school had turned selling newspapers into enough of a business to buy a BMW; who became a billionaire as the founder of a fast-growing, high-tech computer company by the time he was 30; who told his management team that his daughter's first words were "Daddy—kill-IBM, Gateway, Compaq"; who learned from production mistakes and brought in senior managers to help his firm; and who is so private he seldom talks about himself. In other words, you would be thinking of Michael Dell, the founder of Dell Computer, and of his personality.[112]

Personality is the overall combination of characteristics that capture the unique nature of a person as that person reacts to and interacts with others.

Personality combines a set of physical and mental characteristics that reflect how a person looks, thinks, acts, and feels. Sometimes attempts are made to measure personality with questionnaires or special tests. Frequently, personality can be inferred from behavior alone, such as by the actions of Michael Dell. Either way, personality is an important individual characteristic to understand—it helps us identify predictable interplays between people's personalities and their tendencies to behave in certain ways.

Numerous lists of personality traits—enduring characteristics describing an individual's behavior—have been developed, many of which have been used in OB research and can be looked at in different ways. A key starting point is to consider the personality dimensions that recent research has distilled from extensive lists into what is called the "Big Five":[113]

The Big Five personality dimensions

Extraversion—outgoing, sociable, assertive

Agreeableness—good-natured, trusting, cooperative

Conscientiousness—responsible, dependable, persistent

Emotional stability—unworried, secure, relaxed

Openness to experience—imaginative, curious, broad-minded

Standardized personality tests determine how positively or negatively an individual scores on each of these dimensions. For instance, a person scoring high on openness to experience tends to ask lots of questions and to think in new and unusual ways. You can consider a person's individual personality profile across the five dimensions. In terms of job performance, research has shown that conscientiousness predicts job performance across five occupational groups of professions—engineers, police, managers, salespersons, and skilled and semiskilled employees. Predictability of the other dimensions depends on the occupational group. For instance, not surprisingly, extraversion predicts performance for sales and managerial positions.

A second approach to looking at OB personality traits is to divide them into social traits, personal conception traits, and emotional adjustment traits, and then to consider how those categories come together dynamically.[114]

Social traits are surface-level traits that reflect the way a person appears to others when interacting in various social settings. The problem-solving style, based on the work of Carl Jung, a noted psychologist, is one measure representing social traits.[116] It reflects the way a person goes about gathering and evaluating information in solving problems and making decisions.

Social traits are surface-level traits that reflect the way a person appears to others when interacting in social settings.

Problem-solving style reflects the way a person gathers and evaluates information when solving problems and making decisions.

Information gathering involves getting and organizing data for use. Styles of information gathering vary from sensation to intuitive. Sensation-type individuals prefer routine and order and emphasize well-defined details in gathering information; they would rather work with known facts than look for possibilities. By contrast, intuitive-type individuals prefer the "big picture." They like solving new problems, dislike routine, and would rather look for possibilities than work with facts.

The second component of problem solving, evaluation, involves making judgments about how to deal with information once it has been collected. Styles of information evaluation vary from an emphasis on feeling to an emphasis on thinking. Feeling-type individuals are oriented toward conformity and try to accommodate themselves to other people. They try to avoid problems that may result in disagreements. Thinking-type individuals use reason and intellect to deal with problems and downplay emotions.

When these two dimensions (information gathering and evaluation) are combined, four basic problem-solving styles result: sensation-feeling (SF), intuitive-feeling (IF), sensation-thinking (ST), and intuitive-thinking (IT), together with summary descriptions as shown in Figure 2.2.

Research indicates that there is a fit between the styles of individuals and the kinds of decisions they prefer. For example, STs (sensation-thinkers) prefer analytical strategies—those that emphasize detail and method. IFs (intuitive-feelers) prefer intuitive strategies—those that emphasize an overall pattern and fit. Not surprisingly, mixed styles (sensation-feelers or intuitive-thinkers) select both analytical and intuitive strategies. Other findings also indicate that thinkers tend to have higher motivation than do feelers and that individuals who emphasize sensations tend to have higher job satisfaction than do intuitives. These and other findings suggest a number of basic differences among different problem-solving styles, emphasizing the importance of fitting such styles with a task's information processing and evaluation requirements.[117]

Problem-solving styles are most frequently measured by the typically 100-item Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which asks individuals how they usually act or feel in specific situations. Firms such as Apple, AT&T, and Exxon, as well as hospitals, educational institutions, and military organizations, have used the Myers-Briggs for various aspects of management development.[118]

The personal conception traits represent the way individuals tend to think about their social and physical setting as well as their major beliefs and personal orientation concerning a range of issues.

Locus of Control The extent to which a person feels able to control his or her own life is concerned with a person's internal-external orientation and is measured by Rotter's locus of control instrument.[119] People have personal conceptions about whether events are controlled primarily by themselves, which indicates an internal orientation, or by outside forces, such as their social and physical environment, which indicates an external orientation. Internals, or persons with an internal locus of control, believe that they control their own fate or destiny. In contrast, externals, or persons with an external locus of control, believe that much of what happens to them is beyond their control and is determined by environmental forces (such as fate). In general, externals are more extraverted in their interpersonal relationships and are more oriented toward the world around them. Internals tend to be more introverted and are more oriented toward their own feelings and ideas. Figure 2.3 suggests that internals tend to do better on tasks requiring complex information processing and learning as well as initiative. Many managerial and professional jobs have these kinds of requirements.

Proactive Personality Although some people in organizations are passive recipients when faced with constraints, others take direct and intentional action to change their circumstances. The disposition that identifies whether or not individuals act to influence their environments is known as proactive personality. Individuals with high proactive personality identify opportunities and act on them, show initiative, take action, and persevere until meaningful change occurs. In contrast, people who are not proactive fail to identify—let alone seize—opportunities to change things. Less proactive individuals are passive and reactive, preferring to adapt to circumstances rather than change them.[120]

A proactive personality is the disposition that identifies whether or not individuals act to influence their environments.

Given the demanding nature of work environments today, many companies are seeking individuals with more proactive qualities—individuals who take initiative and engage in proactive problem solving. Research supports this, showing that proactive personality is positively related to job performance, creativity, leadership, and career success. Other studies have shown proactive personality related to team effectiveness and entrepreneurship. Moreover, when organizations try to make positive and innovative change, these changes have more positive effects for proactive individuals—they are more involved and more receptive to change.

Taken together, research is providing strong evidence that proactive personality is an important and desirable element in today's work environment.

Figure 2.3. Ways in which those high in internal locus of control differ from those high in external locus of control.

Authoritarianism/Dogmatism Both "authoritarianism" and "dogmatism" deal with the rigidity of a person's beliefs. A person high in authoritarianism tends to adhere rigidly to conventional values and to obey recognized authority. This person is concerned with toughness and power and opposes the use of subjective feelings. An individual high in dogmatism sees the world as a threatening place. This person regards legitimate authority as absolute, and accepts or rejects others according to how much they agree with accepted authority. Superiors who possess these latter traits tend to be rigid and closed. At the same time, dogmatic subordinates tend to want certainty imposed upon them.

Authoritarianism is a tendency to adhere rigidly to conventional values and to obey recognized authority.

Dogmatism leads a person to see the world as a threatening place and to regard authority as absolute.

From an ethical standpoint, we can expect highly authoritarian individuals to present a special problem because they are so susceptible to authority that in their eagerness to comply they may behave unethically.[121] For example, we might speculate that many of the Nazis who were involved in war crimes during World War II were high in authoritarianism or dogmatism; they believed so strongly in authority that they followed unethical orders without question.

Machiavellianism A third personal conceptions dimension is Machiavellianism, which owes its origins to Niccolo Machiavelli. The very name of this sixteenth-century author evokes visions of a master of guile, deceit, and opportunism in interpersonal relations. Machiavelli earned his place in history by writing The Prince, a nobleman's guide to the acquisition and use of power.[122] The subject of Machiavelli's book is manipulation as the basic means of gaining and keeping control of others. From its pages emerges the personality profile of a Machiavellian—someone who views and manipulates others purely for personal gain.

Psychologists have developed a series of instruments called Mach scales to measure a person's Machiavellian orientation.[123] A high-Mach personality is someone who tends to behave in ways consistent with Machiavelli's basic principles. Such individuals approach situations logically and thoughtfully and are even capable of lying to achieve personal goals. They are rarely swayed by loyalty, friendships, past promises, or the opinions of others, and they are skilled at influencing others.

Research using the Mach scales provides insight into the way high and low Machs may be expected to behave in various situations. A person with a "cool" and "detached" high-Mach personality can be expected to take control and try to exploit loosely structured environmental situations but will perform in a perfunctory, even detached, manner in highly structured situations. Low Machs tend to accept direction imposed by others in loosely structured situations; they work hard to do well in highly structured ones. For example, we might expect that, where the situation permitted, a high Mach would do or say whatever it took to get his or her way. In contrast, a low Mach would tend to be much more strongly guided by ethical considerations and would be less likely to lie or cheat or to get away with lying or cheating.

Self-Monitoring A final personal conceptions trait of special importance to managers is self-monitoring. Self-monitoring reflects a person's ability to adjust his or her behavior to external, situational (environmental) factors.[124]

Self-monitoring is a person's ability to adjust his or her behavior to external situational (environmental) factors.

High self-monitoring individuals are sensitive to external cues and tend to behave differently in different situations. Like high Machs, high self-monitors can present a very different appearance from their true self. In contrast, low self-monitors, like their low-Mach counterparts, are not able to disguise their behaviors—"what you see is what you get." There is also evidence that high self-monitors are closely attuned to the behavior of others and conform more readily than do low self-monitors.[125] Thus, they appear flexible and may be especially good at responding to the kinds of situational contingencies emphasized throughout this book. For example, high self-monitors should be especially good at changing their leadership behavior to fit subordinates with more or less experience, tasks with more or less structure, and so on.

The emotional adjustment traits measure how much an individual experiences emotional distress or displays unacceptable acts, such as impatience, irritability, or aggression. Often the person's health is affected if they are not able to effectively manage stress. Although numerous such traits are cited in the literature, a frequently encountered one especially important for OB is the Type A/Type B orientation.[126]

Emotional adjustment traits are traits related to how much an individual experiences emotional distress or displays unacceptable acts.

Type A orientations are characterized by impatience, desire for achievement, and a more competitive nature than Type B.

Type B orientations are characterized by an easygoing and less competitive nature than Type A.

Individuals with a Type A orientation are characterized by impatience, desire for achievement, and perfectionism. In contrast, those with a Type B orientation are characterized as more easygoing and less competitive in relation to daily events.[127] Type A people tend to work fast and to be abrupt, uncomfortable, irritable, and aggressive. Such tendencies indicate "obsessive" behavior, a fairly widespread—but not always helpful—trait among managers. Many managers are hard-driving, detail-oriented people who have high performance standards and thrive on routine. But when such work obsessions are carried to the extreme, they may lead to greater concerns for details than for results, resistance to change, overzealous control of subordinates, and various kinds of interpersonal difficulties, which may even include threats and physical violence. In contrast, Type B managers tend to be much more laid back and patient in their dealings with co-workers and subordinates.

It is but a small step from a focus on the emotional adjustment traits of Type A/Type B orientation to consideration of the relationship between personality and stress. We define stress as a state of tension experienced by individuals facing extraordinary demands, constraints, or opportunities. As we show, stress can be both positive and negative and is an important fact of life in our present work environment.[128]

Stress is tension from extraordinary demands, constraints, or opportunities.

An especially important set of stressors includes personal factors, such as individual needs, capabilities, and personality.[129] Stress can reach a destructive state more quickly, for example, when experienced by highly emotional people or by those with low self-esteem. People who perceive a good fit between job requirements and personal skills seem to have a higher tolerance for stress than do those who feel less competent as a result of a person-job mismatch.[130] Also, of course, basic aspects of personality are important. This is true not only for those with Type A orientation, but also for the Big Five dimensions of neuroticism or negative affectivity; extroversion or positive affectivity; and openness to experience, which suggests the degree to which employees are open to a wide range of experience likely to involve risk taking and making frequent changes.[131]

Any look toward your career future in today's dynamic times must include an awareness that stress is something you, as well as others, are sure to encounter.[132] Stressors are the wide variety of things that cause stress for individuals. Some stressors can be traced directly to what people experience in the workplace, whereas others derive from nonwork and personal factors.

Work Stressors Without doubt, work can be stressful, and job demands can disrupt one's work-life balance. A study of two-career couples, for example, found some 43 percent of men and 34 percent of women reporting that they worked more hours than they wanted to.[133] We know that work stressors can arise from many sources—from excessively high or low task demands, role conflicts or ambiguities, poor interpersonal relations, or career progress that is either too slow or too fast. A list of common stressors includes the following:

Possible work-related stressors

Task demands—being asked to do too much or being asked to do too little

Role ambiguities—not knowing what one is expected to do or how work performance is evaluated

Role conflicts—feeling unable to satisfy multiple, possibly conflicting, performance expectations

Ethical dilemmas—being asked to do things that violate the law or personal values

Interpersonal problems—experiencing bad relationships or working with others with whom one does not get along

Career developments—moving too fast and feeling stretched; moving too slowly and feeling stuck on a plateau

Physical setting—being bothered by noise, lack of privacy, pollution, or other unpleasant working conditions

Life Stressors A less obvious, though important, source of stress for people at work is the spillover effect that results when forces in their personal lives "spill over" to affect them at work. Such life stressors as family events (e.g., the birth of a new child), economic difficulties (e.g., the sudden loss of a big investment), and personal affairs (e.g., a separation or divorce) can all be extremely stressful. Since it is often difficult to completely separate work and nonwork lives, life stressors can affect the way people feel and behave on their jobs as well as in their personal lives.

Even though we tend to view and discuss stress from a negative perspective, it isn't always a negative influence on our lives. Indeed, there are two faces to stress—one positive and one negative.[134] Constructive stress, or eustress, acts in a positive way. It occurs at moderate stress levels by prompting increased work effort, stimulating creativity, and encouraging greater diligence. You may know such stress as the tension that causes you to study hard before exams, pay attention, and complete assignments on time in a difficult class. Destructive stress, or distress, is dysfunctional for both the individual and the organization. One form is the job burnout that shows itself as loss of interest in and satisfaction with a job due to stressful working conditions. When a person is "burned out," he or she feels exhausted, emotionally and physically, and thus unable to deal positively with work responsibilities and opportunities. Even more extreme reactions sometimes appear in news reports of persons who attack others and commit crimes in what is known as "desk rage" and "workplace rage."

Too much stress can overload and break down a person's physical and mental systems, resulting in absenteeism, turnover, errors, accidents, dissatisfaction, reduced performance, unethical behavior, and even illness. Stanford scholar and consultant Jeffrey Pfeffer calls those organizations that create excessive stress for their members "toxic workplaces." A toxic company implicitly says this to its employees: "We're going to put you in an environment where you have to work in a style and at a pace that is not sustainable. We want you to come in here and burn yourself out. Then you can leave."[135]

As is well known, stress can have a bad impact on a person's health. It is a potential source of both anxiety and frustration, which can harm the body's physiological and psychological well-being over time.[136] Health problems associated with distress include heart attacks, strokes, hypertension, migraine headache, ulcers, substance abuse, overeating, depression, and muscle aches. Managers and team leaders should be alert to signs of excessive distress in themselves and their co-workers. Key symptoms are changes from normal patterns—changes from regular attendance to absenteeism, from punctuality to tardiness, from diligent work to careless work, from a positive attitude to a negative attitude, from openness to change to resistance to change, or from cooperation to hostility.

Coping Mechanisms With rising awareness of stress in the workplace, interest is also growing in how to manage, or cope, with distress. Coping is a response or reaction to distress that has occurred or is threatened. It involves cognitive and behavioral efforts to master, reduce, or tolerate the demands that are created by the stressful situation.

Coping is a response or reaction to distress that has occurred or is threatened.

Two major coping mechanisms are those which: (1) regulate emotions or distress (emotion-focused coping), and (2) manage the problem that is causing the distress (problem-focused coping). As described by Susan Folkman, problem-focused coping strategies include: "get the person responsible to change his or her mind," "make a plan of action and follow it," and "stand your ground and fight for what you want." Emotion-focused coping strategies include: "look for the silver lining, try to look on the bright side of things," "accept sympathy and understanding from someone," and "try to forget the whole thing."[137]

Individual differences are related to coping mechanisms. Not surprisingly, neuroticism has been found to be associated with increased use of hostile reaction, escapism/fantasy, self-blame, sedation, withdrawal, wishful thinking, passivity, and indecisiveness. On the other hand, people high in extraversion and optimism use rational action, positive thinking, substitution, and restraint. And individuals high in openness to experience are likely to use humor in dealing with stress. In other words, the more your personality allows you to approach the situation with positive affect the better off you will be.

Stress Prevention Stress prevention is the best first-line strategy in the battle against stress. It involves taking action to keep stress from reaching destructive levels in the first place. Work and life stressors must be recognized before one can take action to prevent their occurrence or to minimize their adverse impacts. Persons with Type A personalities, for example, may exercise self-discipline; supervisors of Type A employees may try to model a lower-key, more relaxed approach to work. Family problems may be partially relieved by a change of work schedule; simply knowing that your supervisor understands your situation may also help to reduce the anxiety caused by pressing family concerns.

Personal Wellness Once stress has reached a destructive point, special techniques of stress management can be implemented. This process begins with the recognition of stress symptoms and continues with actions to maintain a positive performance edge. The term "wellness" is increasingly used these days. Personal wellness involves the pursuit of one's job and career goals with the support of a personal health promotion program. The concept recognizes individual responsibility to enhance and maintain wellness through a disciplined approach to physical and mental health. It requires attention to such factors as smoking, weight, diet, alcohol use, and physical fitness. Organizations can benefit from commitments to support personal wellness. A University of Michigan study indicates that firms have saved up to $600 per year per employee by helping them to cut the risk of significant health problems.[139] Arnold Coleman, CEO of Healthy Outlook Worldwide, a health fitness consulting firm, states: "If I can save companies 5 to 20 percent a year in medical costs, they'll listen. In the end you have a well company and that's where the word 'wellness' comes from."[140]

Personal wellness involves the pursuit of one's job and career goals with the support of a personal health promotion program.

Organizational Mechanisms On the organizational side, there is an increased emphasis today on employee assistance programs designed to provide help for employees who are experiencing personal problems and the stress associated with them. Common examples include special referrals on situations involving spousal abuse, substance abuse, financial difficulties, and legal problems. In such cases, the employer is trying to at least make sure that the employee with a personal problem has access to information and advice on how to get the guidance and perhaps even treatment needed to best deal with it. Organizations that build positive work environments and make significant investments in their employees are best positioned to realize the benefits of their full talents and work potential. As Pfeffer says: "All that separates you from your competitors are the skills, knowledge, commitment, and abilities of the people who work for you. Organizations that treat people right will get high returns."[141] That, in essence, is what the study of organizational behavior is all about.

Values can be defined as broad preferences concerning appropriate courses of action or outcomes. As such, values reflect a person's sense of right and wrong or what "ought" to be.[142] "Equal rights for all" and "People should be treated with respect and dignity" are representative of values. Values tend to influence attitudes and behavior. For example, if you value equal rights for all and you go to work for an organization that treats its managers much better than it does its workers, you may form the attitude that the company is an unfair place to work; consequently, you may not produce well or may perhaps leave the company. It is likely that if the company had had a more egalitarian policy, your attitude and behaviors would have been more positive.

Values are broad preferences concerning appropriate courses of action or outcomes.

Parents, friends, teachers, siblings, education, experience, and external reference groups are all value sources that can influence individual values. Indeed, peoples' values develop as a product of the learning and experience they encounter from various sources in the cultural setting in which they live. As learning and experiences differ from one person to another, value differences result. Such differences are likely to be deep seated and difficult (though not impossible) to change; many have their roots in early childhood and the way a person has been raised.[143]

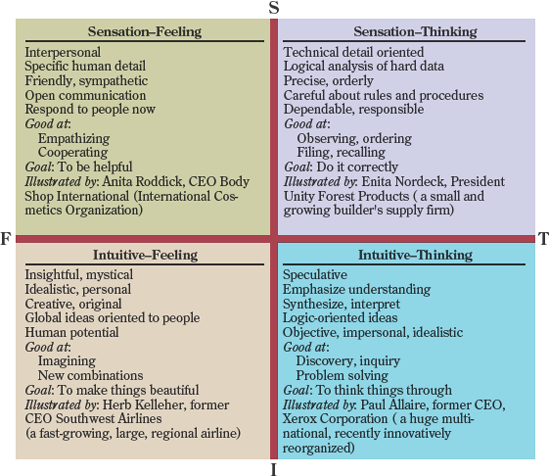

The noted psychologist Milton Rokeach has developed a well-known set of values classified into two broad categories.[144] Terminal values reflect a person's preferences concerning the "ends" to be achieved; they are the goals an individual would like to achieve during his or her lifetime. Rokeach divides values into 18 terminal values and 18 instrumental values as summarized in Figure 2.4. Instrumental values reflect the "means" for achieving desired ends. They represent how you might go about achieving your important end states, depending on the relative importance you attached to the instrumental values.

Terminal values reflect a person's preferences concerning the "ends" to be achieved.

Instrumental values reflect a person's beliefs about the means to achieve desired ends.

Illustrative research shows, not surprisingly, that both terminal and instrumental values differ by group (for example, executives, activist workers, and union members).[145] These preference differences can encourage conflict or agreement when different groups have to deal with each other.

Another frequently used classification of human values has been developed by psychologist Gordon Allport and his associates. These values fall into six major types:[146]

Alport's six value categories

Theoretical—interest in the discovery of truth through reasoning and systematic thinking

Economic—interest in usefulness and practicality, including the accumulation of wealth

Aesthetic—interest in beauty, form, and artistic harmony

Social—interest in people and love as a human relationship

Political—interest in gaining power and influencing other people

Religious—interest in unity and in understanding the cosmos as a whole

Once again, groups differ in the way they rank order the importance of these values. Examples are: ministers—religious, social, aesthetic, political, theoretical, economic; purchasing executives—economic, theoretical, political, religious, aesthetic, social; industrial scientists—theoretical, political, economic, aesthetic, religious, social.[147]

The previous value classifications have had a major impact on the values literature, but they were not specifically designed for people in a work setting. A more recent values schema, developed by Bruce Meglino and associates, is aimed at people in the workplace:[148]

Meglino and associates' value categories

Achievement—getting things done and working hard to accomplish difficult things in life

Helping and concern for others—being concerned for other people and with helping others

Honesty—telling the truth and doing what you feel is right

Fairness—being impartial and doing what is fair for all concerned

These four values have been shown to be especially important in the workplace; thus, the framework should be particularly relevant for studying values in OB.

In particular, values can be influential through value congruence, which occurs when individuals express positive feelings upon encountering others who exhibit values similar to their own. When values differ, or are incongruent, conflicts over such things as goals and the means to achieve them may result. Meglino and colleagues' value schema was used to examine value congruence between leaders and followers. The researchers found greater follower satisfaction with the leader when there was such congruence in terms of achievement, helping, honesty, and fairness values.[149]

Patterns and Trends in Values We should also be aware of applied research and insightful analyses of values trends over time. Daniel Yankelovich, for example, is known for his informative public opinion polls among North American workers, and William Fox has prepared a carefully reasoned book analyzing values trends.[150] Both Yankelovich and Fox note movements away from earlier values, with Fox emphasizing a decline in such shared values as duty, honesty, responsibility, and the like, while Yankelovich notes a movement away from valuing economic incentives, organizational loyalty, and work-related identity. The movement is toward valuing meaningful work, pursuit of leisure, and personal identity and self-fulfillment. Yankelovich believes that the modern manager must be able to recognize value differences and trends among people at work. For example, he reports finding higher productivity among younger workers who are employed in jobs that match their values and/or who are supervised by managers who share their values, reinforcing the concept of value congruence.

In a nationwide sample, managers and human resource professionals were asked to identify the work-related values they believed to be most important to individuals in the workforce, both now and in the near future.[151] The nine most popular values named were recognition for competence and accomplishments, respect and dignity, personal choice and freedom, involvement at work, pride in one's work, lifestyle quality, financial security, self-development, and health and wellness. These values are especially important for managers because they indicate some key concerns of the new workforce. Even though each individual worker places his or her own importance on these values, and even though the United States today has by far the most diverse workforce in its history, this overall characterization is a good place for managers to start when dealing with workers in the new workplace. It is important to remember, however, that although values are individual preferences, many tend to be shared within cultures and organizations.

The word "culture" is frequently used in organizational behavior in connection with the concept of corporate culture, the growing interest in workforce diversity, and the broad differences among people around the world. Specialists tend to agree that culture is the learned, shared way of doing things in a particular society. It is the way, for example, in which its members eat, dress, greet and treat one another, teach their children, solve everyday problems, and so on.[152] Geert Hofstede, a Dutch scholar and consultant, refers to culture as the "software of the mind," making the analogy that the mind's "hardware" is universal among human beings.[153] But the software of culture takes many different forms. We are not born with a culture; we are born into a society that teaches us its culture. And because culture is shared among people, it helps to define the boundaries between different groups and affect how their members relate to one another.

Culture is the learned and shared way of thinking and acting among a group of people or society.

Cultures vary in their underlying patterns of values and attitudes. The way people think about such matters as achievement, wealth and material gain, and risk and change may influence how they approach work and their relationships with organizations. A framework developed by Geert Hofstede offers one approach for understanding how value differences across national cultures can influence human behavior at work. The five dimensions of national culture in his framework can be described as follows:[154]

Hofstede's dimensions of national cultures

Power distance is the willingness of a culture to accept status and power differences among its members. It reflects the degree to which people are likely to respect hierarchy and rank in organizations. Indonesia is considered a high-power-distance culture, whereas Sweden is considered a relatively low-power-distance culture.

Uncertainty avoidance is a cultural tendency toward discomfort with risk and ambiguity. It reflects the degree to which people are likely to prefer structured versus unstructured organizational situations. France is considered a high uncertainty avoidance culture, whereas Hong Kong is considered a low uncertainty avoidance culture.

Individualism-collectivism is the tendency of a culture to emphasize either individual or group interests. It reflects the degree to which people are likely to prefer working as individuals or working together in groups. The United States is a highly individualistic culture, whereas Mexico is a more collectivist one.

Masculinity-femininity is the tendency of a culture to value stereotypical masculine or feminine traits. It reflects the degree to which organizations emphasize competition and assertiveness versus interpersonal sensitivity and concerns for relationships. Japan is considered a very masculine culture, whereas Thailand is considered a more feminine culture.

Long-term/short-term orientation is the tendency of a culture to emphasize values associated with the future, such as thrift and persistence, or values that focus largely on the present. It reflects the degree to which people and organizations adopt long-term or short-term performance horizons. South Korea is high on long-term orientation, whereas the United States is a more short-term-oriented country.

Uncertainty avoidance is the cultural tendency to be uncomfortable with uncertainty and risk in everyday life.

Individualism-collectivism is the tendency of members of a culture to emphasize individual self-interests or group relationships.

Masculinity-femininity is the degree to which a society values assertiveness or relationships.

Long-term/short-term orientation is the degree to which a culture emphasizes long-term or short-term thinking.

The first four dimensions in Hofstede's framework were identified in an extensive study of thousands of employees of a multinational corporation operating in more than 40 countries.[155] The fifth dimension of long-term/short-term orientation was added from research using the Chinese Values Survey conducted by cross-cultural psychologist Michael Bond and his colleagues.[156] Their research suggested the cultural importance of Confucian dynamism, with its emphasis on persistence, the ordering of relationships, thrift, sense of shame, personal steadiness, reciprocity, protection of "face," and respect for tradition.[157]

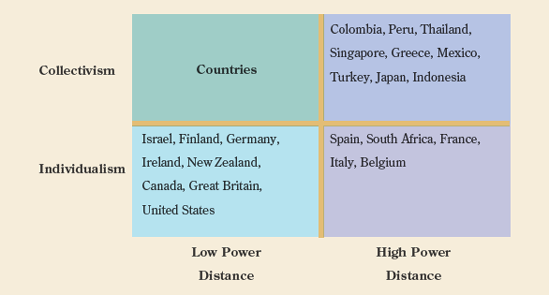

When using the Hofstede framework, it is important to remember that the five dimensions are interrelated, not independent.[158] National cultures may best be understood in terms of cluster maps or collages that combine multiple dimensions. For example, Figure 2.5 shows a sample grouping of countries based on individualism-collectivism and power distance. Note that high power distance and collectivism are often found together, as are low power distance and individualism. Whereas high collectivism may lead us to expect a work team in Indonesia to operate by consensus, the high power distance may cause the consensus to be heavily influenced by the desires of a formal leader. A similar team operating in more individualist and low-power-distance Great Britain or America might make decisions with more open debate, including expressions of disagreement with a leader's stated preferences.

At the national level, cultural value dimensions, such as those identified by Hofstede, tend to influence the previously discussed individual sources of values. The sources, in turn, tend to share individual values, which are then reflected in the recipients' value structures. For example, in the United States the sources would tend to be influenced by Hofstede's low-power-distance dimensions (along with his others, of course), and the recipients would tend to interpret their own individual value structures through that low-power-distance lens. Similarly, people in other countries or societies would be influenced by their country's standing on such dimensions.

We started this chapter by saying that individual differences are important because they can offer great benefits. The discussion now comes full circle with the topic of diversity.

Interest in workplace diversity gained prominence years ago when it became clear that the demographic make-up of the workforce was going to experience dramatic changes. At that time the workforce was primarily white male. Since then workforce diversity has increased in both the United States and much of the rest of the world, and white males are no longer the majority in the labor force.

The focus on diversity is important, however, not just because of demographic trends but because of the benefits diverse backgrounds and perspectives can bring to the workplace. Rather than being something we have to "manage," current perspectives focus on diversity as a key element of the "Global War for Talent." As described by Rob Mclnness in Diversity World:

It is clear that the greatest benefits of workforce diversity will be experienced not by the companies that have learned to employ people in spite of their differences, but by the companies that have learned to employ people because of them.[160]

From this perspective, workforce diversity refers to a mix of people within a workforce who are considered to be, in some way, different from those in the prevailing constituency. Seven important reasons for organizations to engage policies, practices, and perspectives to diversify their workforces are:[161]

Workforce diversity is a mix of people within a workforce who are considered to be, in some way, different from those in the prevailing constituency.

Resource Imperative: Today's talent is overwhelmingly represented by people from a vast array of backgrounds and life experiences. Competitive companies cannot allow discriminatory preferences and practices to impede them from attracting the best available talent.

Capacity-Building Strategy: Tumultuous change is the norm. Companies that prosper have the capacity to effectively solve problems, rapidly adapt to new situations, readily identify new opportunities, and quickly capitalize on them. This capacity is only realized by a diverse range of talent, experience, knowledge, insight, and imagination in their workforces.

Marketing Strategy: To ensure that products and services are designed to appeal to the buying power of diverse customer bases, "smart" companies are hiring people from all walks of life for their specialized insights and knowledge; the makeup of their workforce reflects their customer base.

Business Communications Strategy: All organizations are seeing a growing diversity in the workforces around them—their vendors, partners, and customers. Those that choose to retain homogenous workforces will likely find themselves increasingly ineffective in their external interactions and communications.

Economic Payback: Many groups of people who have been excluded from workplaces are consequently reliant on tax-supported social service programs. Diversifying the workforce, particularly through initiatives like welfare-to-work, can effectively turn tax users into taxpayers.

Social Responsibility: By diversifying our workforces we can help people who are "disadvantaged" in our communities get opportunities to earn a living and achieve their dreams.

Legal Requirement: Many employers are under legislative mandates to be nondiscriminatory in their employment practices. Noncompliance with Equal Employment Opportunity or Affirmative Action legislation can result in fines and/or loss of contracts with government agencies.

Given that diversity addresses how people differ from one another in terms of physical or societal characteristics, it can be considered from many perspectives, including demographic (gender, race/ethnicity, age), disability, economic, religion, sexual orientation, marital status, parental status, and even others. Since we cannot address all of them here, this section focuses on several key topics.

Gender Women now comprise 46.3 percent of U.S. business and 50 percent of management, professional, and related occupations. Even though this number has been increasing steadily over the last 60 years, women are still underrepresented at the highest levels of organizations.[162] Catalyst, a leading source of information on women in business (see Figure 2.7), tracks the number of women on Fortune 500 boards and in corporate officer positions (the highest-level executives who are often board-appointed or board approved).[163] Findings show that women have steadily gained access to the elite level of corporate leadership, but in the last two years this progress has stalled.[164] Women as top earners and CEOs lag far behind men, with women making up only 3 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs and 6.2 percent of Fortune 500 top earners (see Figure 2.6). As indicated in a Catalyst report,[165] the situation is even more difficult for women of color. In 2005, only 5 percent of all managers, professionals, and related occupations were African-American women; Latinas constituted 3.3 percent, and Asian women 2.6 percent. In Europe the numbers are slightly different, but show a similar pattern. In 2005, women (regardless of race/ethnicity) represented 44 percent of the workforce, 30 percent of managerial positions, and only 3 percent of company CEOs.[166]

![The Catalyst Pyramid of U.S. Women in Business. [Source: Based on Catalyst.org/132/us-women-in-business (March, 2009). Used by permission].](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__0206.png)

Figure 2.6. The Catalyst Pyramid of U.S. Women in Business. [Source: Based on Catalyst.org/132/us-women-in-business (March, 2009). Used by permission].

Why should we care about this? Because research shows that companies with a higher percentage of female board directors and corporate officers, on average, financially outperform companies with the lowest percentages by significant margins.[167] Women leaders are also beneficial because they encourage more women in the pipeline and act as role models and mentors for younger women. Moreover, the presence of women leaders sends important signals that an organization has a broader and deeper talent pool, is an "employer of choice," and offers an inclusive workplace.

The Leaking Pipeline Recognition that women have not penetrated the highest level, and even worse, that they are abandoning the corporate workforce just as they are positioned to attain these levels, has gained the attention of many organizations. The phrase leaking pipeline was coined to describe this phenomenon. The leaking pipeline theory gained credence with a study by Professor Lynda Gratton of the London Business School.[168] In her study she examined 6l organizations operating in 12 European countries and found that the number of women decreases the more senior the roles become.

Although research is just beginning to examine what is behind the leaking pipeline, one reason being discussed is potential stereotyping. Catalyst research[169] finds that women consistently identify gender stereotypes as a significant barrier to advancement. They describe the stereotyping as the "think-leader-think-male" mindset: the idea that men are largely seen as the leaders by default. When probed further, both men and women saw women as better at stereotypically feminine "caretaking skills," such as supporting and encouraging others, and men as excelling at more conventionally masculine "taking charge" skills, such as influencing superiors and problem solving—characteristics previously shown to be essential to leadership. These perceptions are even more salient in traditionally male-dominated fields, such as engineering and law, where women are viewed as "out of place" and have to put considerable effort into proving otherwise.

stereotyping occurs when people make a generalization, usually exaggerated or oversimplified (and potentially offensive) that is used to describe or distinguish a group.

This creates a problem in terms of a double bind for women, meaning that there is no easy choice. If they conform to the stereotype they are seen as weak; if they go against the stereotype they are going against norms of femininity. As some describe, it creates a situation of "damned if they do, doomed if they don't."[170]

The impact of stereotypic bias is often underestimated. Some believe that given the predominance of the stereotypes they must reflect real differences. However, research has shown they misrepresent reality: Gender is not a reliable predictor of how people will lead.[171] In fact, studies show that women outrank men on 42 of 52 executive competencies. Others believe that progress has been made so there is not a problem. As pointed out earlier, however, while progress has been made in management ranks, the same is not true at corporate officer levels. Given that approximately 50 percent of managerial positions have been occupied by women since 1990, we could expect current percentages of women at the highest levels to be higher than 2–3 percent.

What can companies do? One suggestion would be to address stereotypes and biases and consider the additional pressures placed on women as they work to meet the already challenging demands of executive environments. As Catalyst reports, "Ultimately, it is not women's leadership styles that need to change but the structures and perceptions that must keep up with today's changing times." Some things managers can do to change limiting structures and perceptions include:[172]

Communicate leadership appointment opportunities and decision processes transparently (rather than based on who you know).

Encourage females to communicate interest in, and apply for, leadership positions.

Provide mentoring and development infrastructure for high potential female managers that are geared to their unique needs.

Actively monitor and analyze satisfaction levels of the women managed/coached/mentored.

Support career development through the family years—not seeing the woman as "not motivated" or the family as a delay in her career path.

Emphasize personal and family goals, and more meaningful work that makes it worth staying in the workplace—stop the exodus of women poised to obtain top roles.

Create organizational cultures that are more satisfying to women (e.g., less militaristic, less command-and-control, less status-based and more meaning-based).

Measure performance through results—with less emphasis on "face-time."

Value leadership styles that are more inclusive and collaborative and rely less on a high degree of hierarchy.

Race and Ethnicity Racial and ethnic differences represent another prominent form of diversity in organizations. In the workplace, race and ethnicity are protected from discrimination by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This act protects individuals against employment discrimination on the basis of race and color, as well as national origin, sex, and religion. It applies to employers with 15 or more employees, including state and local governments.[173] It also applies to employment agencies and to labor organizations, as well as to the federal government. According to Title VII, equal employment opportunity cannot be denied any person because of his/her racial group or perceived racial group, his/her race-linked characteristics (e.g., hair texture, color, facial features), or because of his/her marriage to or association with someone of a particular race or color. It also prohibits employment decisions based on stereotypes and assumptions about abilities, traits, or the performance of individuals of certain racial groups.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects individuals against employment discrimination on the basis of race and color, national origin, sex, and religion.

Title VII's prohibitions apply regardless of whether the discrimination is directed at Whites, Blacks, Asians, Latinos, Arabs, Native Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, multi-racial individuals, or persons of any other race, color, or ethnicity. It covers issues of recruiting, hiring and promotion, transfer, work assignments, performance measurements, the work environment, job training, discipline and discharge, wages and benefits, and any other term, condition, or privilege of employment.

A Focus on Inclusion While in the past many organizations addressed the issue of racial and ethnic diversity from the standpoint of compliance (e.g., complying with the legal mandate by employing an Employment Equity and Affirmative Action Officer who kept track of and reported statistics), in recent years we have experienced a shift from a focus on diversity to a focus on inclusion. As described by Katharine Esty,[174] "This sea change has happened without fanfare and almost without notice. In most organizations, the word inclusion has been added to all the company's diversity materials with no explanation." As Esty explains, this change represents a shift from a numbers game to a focus on culture, and consideration of how organizations can create inclusive cultures for everyone.

The move from diversity to inclusion occurred primarily because employers began to learn that, although they were able to recruit diverse individuals, they were not able to retain them. In fact, some organizations found that after years of trying, they had lower representation among certain groups than they had earlier. They pieced together that this was related to the fact that the upper ranks of organizations continued to be primarily white male. In these environments awareness and diversity training was not enough—they needed to go more deeply. So, they asked different questions: Do employees in all groups and categories feel comfortable and welcomed in the organization? Do they feel included, and do they experience the environment as inclusive?[175]

Social Identity Theory As research shows, these questions are important because they relate to what social psychologists Henri Tajfel and John Turner termed social identity theory.[176] Social identity theory was developed to understand the psychological basis of discrimination. It describes individuals as having not one but multiple "personal selves" that correspond with membership in different social groups. For example, you have different "identities" depending on your group memberships: you may have an identity as a woman, a Latina, an "Alpha Delta Pi" sorority sister, etc. Social identity theory says that just the mere act of categorizing yourself as a member of a group will lead you to have favoritism toward that group. This favoritism will be displayed in the form of "in-group" enhancement at the expense of the out-group. In other words, by becoming a member of Alpha Delta Pi you enhance the status of that group and positively differentiate Alpha Delta Pi relative to the other sororities.

Social identity theory is a theory developed to understand the psychological basis of discrimination.

In terms of race and ethnicity, social identity theory suggests that simply by having racial or ethnic groups it becomes salient in people's minds; individuals will feel these identities and engage in-group and out-group categorizations. In organizational contexts these categorizations can be subtle but powerful—and primarily noticeable to those in the "out-group" category. Organizations may not intend to create discriminatory environments, but having only a few members of a group may evoke a strong out-group identity. This may make them feel uncomfortable and less a part of the organization.

In-group occurs when individuals feel part of a group and experience favorable status and a sense of belonging.

Out-group occurs when one does not feel part of a group and experiences discomfort and low belongingness

Age It is getting harder to have discussions with managers today without the issue of age differences arising. Age, or more appropriately generational, diversity is affecting the workplace like never before. And seemingly everyone has an opinion!

The controversy is being generated from Millenials, Gen Xers, and Baby Boomers mixing in the workplace—and trying to learn how to get along. Baby Boomers, the postwar generation born between 1946 and 1964, make up about 40 percent of today's workforce. Generation X, born between 1965 and 1980, make up about 36 percent of the workplace. Millenials, born between roughly 1981 and 2000, make up about 16 percent of the workforce (with the remaining 8 percent Matures, born between 1922 and 1945). The primary point of conflict: work ethic. Baby Boomers believe that Millenials are not hard working and are too "entitled." Baby Boomers value hard work, professional dress, long hours, and paying their dues—earning their stripes slowly.[177] Millenials believe Baby Boomers and Gen Xers are more concerned about the hours they work than what they produce. Millenials value flexibility, fun, the chance to do meaningful work right away, and "customized" careers that allow them the choice to go at the pace they want.

The generational mix provides an excellent example of diversity in action. Workforces that are more diverse have individuals with different backgrounds, values, perspectives, opinions, styles, etc. If the groups involved can learn to capitalize on these differences, they can create a work environment more beneficial for all. For example, one thing Millenials can bring to the workplace is their appreciation for gender equality and sexual, cultural, and racial diversity—Millenials embrace these concepts more than any previous generation. Millenials also have an appreciation for community and collaboration. They can help create a more relaxed workplace that reduces some of the problems that come from too much focus on status and hierarchy.[178] Boomers and Gen Xers bring a wealth of experience, dedication, and commitment that contribute to productivity, and a sense of professionalism that is benefiting their younger counterparts. Together, Millenials and Gen Xers may be able to satisfy the Gen X desire for work-life balance through greater demand for more flexible scheduling and virtual work. Accomplishing such changes will come when all the generations learn to understand, respect—and maybe even like—one another.

Disability In recent years the "disability rights movement" has been working to bring attention and support to the needs of disabled workers.[179] The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has been a significant catalyst in advancing their efforts. The ADA is a comprehensive federal civil-rights statute signed into law in 1990 to protect the rights of people with disabilities, and is parallel to acts previously established for women and racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. It prohibits discrimination and mandates that disabled Americans be accorded equality in pursuing jobs, goods, services, and other opportunities.

The focus of the ADA is to eliminate employers' practices that make people with disabilities unnecessarily different. Disabilities include any form of impairment (loss or abnormality of psychological or anatomical structure or function), disability (any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being), or handicap (a disadvantage resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfillment of a role that is normal, depending on age, sex, social, and cultural factors, for that individual).

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a federal civil-rights statute that protects the rights of people with disabilities.

A disability is any form of impairment or handicap.

The ADA has helped to generate a more inclusive climate where organizations are reaching out more to people with disabilities. The most visible changes from the ADA have been in issues of universal design—the practice of designing products, buildings, public spaces, and programs to be usable by the greatest number of people. You may see this in your own college or university's actions to make their campus and classrooms more accessible.[180]

The disability rights movement is working passionately to advance a redefinition of what it means to be disabled in American society. The goal is to overcome the "stigmas" attached to disability. A stigma is a phenomenon whereby an individual with an attribute, which is deeply discredited by his/her society, is rejected as a result of the attribute. Because of stigmas, many are reluctant to seek coverage under the ADA because they do not want to experience discrimination in the form of stigmas.

Stigma is a phenomenon whereby an individual is rejected as a result of an attribute that is deeply discredited by his/her society, is rejected as a result of the attribute.

Estimates indicate that over 50 million Americans have one or more physical or mental disabilities. Even though recent studies report that disabled workers do their jobs as well as, or better than, nondisabled workers, nearly three-quarters of severely disabled persons are reported to be unemployed. Almost 80 percent of those with disabilities say they want to work.[181] Therefore, the need to address issues of stigmas and accessibility for disabled workers is not trivial.

As companies continue to appreciate the value of diversity and activists continue to work to "de-stigmatize" disabilities by working toward a society in which physical and mental differences are accepted as normal and expected—not abnormal or unusual—we can expect to see even greater numbers of disabled workers. This may be accelerated by the fact that the cost of accommodating these workers has been shown to be low.[182]

Sexual Orientation The issue of sexual orientation is also gaining attention in organizations. A December 2008 Newsweek poll shows that 87 percent of Americans believe that gays and lesbians should have equal rights in terms of job opportunities.[184] Moreover, many businesses are paying close attention to statistics showing that the gay market segment is one of the fastest growing segments in the United States. The buying power of the gay/lesbian market is set to exceed $835 billion by 2011.[185] Companies wanting to tap into this market will need employees who understand and represent it.

Although sexual orientation is not protected by the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC), which addresses discrimination based on race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, and disability,[186] some states have executive orders protecting the rights of gay and lesbian workers. The first state to pass a law against workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation was Wisconsin in 1982.[187] As of January 2008, thirteen states prohibited workplace discrimination against gay people, while seven more had extended such protections to LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) people.

Regardless of legislation, findings are beginning to show that the workplace is improving for gay Americans. Thirty years ago the first U.S. corporation added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy. Can you guess who it was? The company was AT&T and its chairman John DeButts.[189] He made the statement that his company would "respect the human rights of our employees." This action opened the door for other companies, which then began adding same-sex domestic partners to health insurance benefits. In 2007, John Browne, CEO of oil and gas producer BP PLC, said: "If we want to be an employer of the most able people who happen to be gay or lesbian, we won't succeed unless we offer equal benefits for partners in same-sex relationships."

Browne reflects the attitude of a growing list of companies that are extending rights to gay and lesbian workers. In 2007, 4,463 companies offered health insurance benefits to employees' domestic partners, and 2,162 employers have nondiscrimination policies covering sexual orientation. The higher a company is on the Fortune 500 list, the more likely it is to have both domestic partner benefits and a written nondiscrimination policy covering sexual orientation.[190] Among the companies listed as most friendly to gays are Disney, Google, US Airways, the New York Times Co., Ford, Nike, and PepsiCo.

Human Rights Campaign As noted by the Human Rights Campaign president Joe Solmonese, "Each of these companies is working hard to transform their workplaces and make them safer for millions of employees around the country. We can now say that at least 10 million employees are protected on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity on the job."[191]

While there is still a long way to go, as more gays and lesbians have become open about their sexuality at work and elsewhere, attitudes are changing. Companies are beginning to understand that respecting and recruiting gay employees is good for the employees—and good for the bottom line.

The concept of valuing diversity in organizations emphasizes appreciation of differences in creating a setting where everyone feels valued and accepted. Valuing diversity assumes that groups will retain their own characteristics and will shape the firm as well as be shaped by it, creating a common set of values that will strengthen ties with customers, enhance recruitment, and contribute to organizations and society. Sometimes diversity management is resisted because of fear of change and discomfort with differences. But as Dr. Santiago Rodriguez, Director of Diversity for Microsoft, says, true diversity is exemplified by companies that "hire people who are different— knowing and valuing that they will change the way you do business."

So how do managers and firms deal with all this? By committing to the creation of environments that welcome and embrace inclusion and working to promote a better understanding of factors that help support inclusion in organizations. The most prominent of these include:[192]

Strong commitment to inclusion from the Board and Corporate Officers

Influential mentors and sponsors who can help provide career guidance and navigate politics

Opportunities for networking with influential colleagues

Role models from same-gender, racial, or ethnic group

Exposure through high visibility assignments

An inclusive culture that values differences and does not require extensive adjustments to fit in

Work to acknowledge and reduce subtle and subconscious stereotypes and stigmas

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 2.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 2 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What are individual differences and why are they important?

The study of individual differences attempts to identify where behavioral tendencies are similar and where they are different to be able to more accurately predict how and why people behave as they do.

For people to capitalize on individual differences they need to be aware of them. Self-awareness is being aware of our own behaviors, preferences, styles, biases, and personalities; awareness of others means being aware of these same things in others.

Self-concept is the view individuals have of themselves as physical, social, and spiritual or moral beings. It is a way of recognizing oneself as a distinct human being.

The nature/nurture controversy addresses whether we are the way we are because of heredity, or because of the environments in which we have been raised and live.

What is personality?

Personality captures the overall profile, or combination of characteristics, that represents the unique nature of an individual as that individual interacts with others.

Personality is determined by both heredity and environment; across all personality characteristics, the mix of heredity and environment is about 50–50. The Big Five personality traits consist of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience.

A useful personality framework consists of social traits, personal conception traits, emotional adjustment traits, and personality dynamics, where each category represents one or more personality dimensions.

How are personality and stress related?

Stress emerges when people experience tensions caused by extraordinary demands, constraints, or opportunities in their jobs.

Personal stressors derive from personality type, needs, and values; they can influence how stressful different situations become for different people.

Work stressors arise from such things as excessive task demands, interpersonal problems, unclear roles, ethical dilemmas, and career disappointments.

Nonwork stress can spill over to affect people at work; nonwork stressors may be traced to family situations, economic difficulties, and personal problems.

Stress can be managed by prevention—such as making adjustments in work and nonwork factors; it can also be dealt with through coping mechanisms and personal wellness—taking steps to maintain a healthy body and mind capable of better withstanding stressful situations.

What are value differences and how do they vary across cultures?

Values are broad preferences concerning courses of action or outcomes.