chapter at a glance

Organizations are collections of people working together to achieve common goals. In this chapter, we discuss organizational goals and how organizations structure themselves to reach them. Here's what to look for in Chapter 16. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF ORGANIZATIONAL GOALS?

Societal Goals

Output Goals

Systems Goals

WHAT ARE THE HIERARCHICAL ASPECTS OF ORGANIZATIONS?

Organizations as Hierarchies

Controls Are a Basic Feature

Centralization and Decentralization

HOW IS WORK ORGANIZED AND COORDINATED?

Traditional Types of Departments

Coordination

WHAT ARE BUREAUCRACIES AND WHAT ARE THE COMMON FORMS?

Mechanistic Structure and the Machine Bureaucracy

Organic Structures and the Professional Bureaucracy

Hybrid Structures

In March 2008, the new owners of the WNBA's Seattle Storm announced that Karen Bryant would be the new Storm CEO. Known as KB, she was a local high school basketball superstar with a modest record as a collegian. As a high school coach she had a three-year record of 24 and 44 before leaving coaching and basketball. Yet, she returned to basketball as an executive. Unfortunately, her first stint as a professional basketball executive looked like a failure when the local professional team and league folded. But Bryant did not quit, and rebounded with a top position with the Seattle Storm team.

"Now, there's no lack of clarity."

When the matched men's team, the Seattle Supersonics, was sold and moved to Oklahoma, four local businesswomen and community leaders bought the women's team and set it free from the confines of the men's program. The new owners created Force 10 Hoops LLC and said they needed an experienced executive who could set realistic goals and develop a structure to reach these targets. The owners wanted a fresh start.

Regarding the change, Bryant said, "Sometimes there were other priorities. Now, there's no lack of clarity. There's no confusion about what our resources are, nor are there any surprises." According to Bryant, the goals are clear and compatible, (1) world class basketball, (2) fan accessibility and affordability, (3) maintaining a sense of community, and (4) creating a successful business model.

In a very short time, Bryant built a successful business model without the deep pockets so typical of professional sports team owners. The successful business model was based on fielding a competitive team, ticket prices that allow the whole family to attend a game, and extensive community involvement. In 2009, Force 10 Hoops was honored as "Business of the Year," by the King County Municipal League.

the key is to match structures to goals

The notion that organizations have goals is very familiar to us simply because our world is one of organizations.[748] Most of us are born, go to school, work, and retire in organizations. Without organizations and their limited, goal-directed behavior, modern societies would simply cease to function. We would need to revert to older forms of social organization based on royalty, clans, and tribes. Organizational goals are so pervasive we rarely give them more than passing notice. Karen Bryant of the Seattle Storm basketball team can easily list the firm's goals. She knows the type of social contribution it makes, whom it serves, and the myriad ways of improving its performance.

Bryant is also aware that corporate goals are common to individuals within the firm only to the extent that an individual's interests can be partially served by the organization. And she understands that the pattern of goals selected and emphasized can help to motivate members and gain support from outsiders.[749]

No firm can be all things to all people. By selecting goals, firms also define who they are and what they will try to become. The choice of goals involves the type of contribution the firm makes to the larger society and the types of outputs it seeks. Managers decide how to link conditions considered desirable for enhanced survival prospects with its societal and output desires.[750] From these basic choices, executives can work with subordinates to develop ways of accomplishing the chosen targets. As we saw with Force 10 Hoops, LLC, the goals of the firm should be consistent and compatible with the way in which it is organized.

Organizations do not operate in a social vacuum but rather they reflect the needs and desires of the societies in which they operate. Societal goals reflect an organization's intended contributions to the broader society.[751] Organizations normally serve a specific societal function or an enduring need of the society. Astute top-level managers build on the professed societal contribution of the organization by relating specific organizational tasks and activities to higher purposes. By contributing to the larger society, organizations gain legitimacy, a social right to operate, and more discretion for their nonsocietal goals and operating practices. By claiming to provide specific types of societal contributions, an organization can also make legitimate claims over resources, individuals, markets, and products. For instance, would you not want a higher salary to work for a tobacco firm than a health food store? Tobacco firms are heavily taxed and under increasing pressure for regulation because their societal contribution is highly questionable.

Often, the social contribution of the firm is a part of its mission statement. Mission statements are written statements of organizational purpose. Weaving a mission statement together with an emphasis on implementation to provide direction and motivation is an executive order of the first magnitude. A good mission statement says whom the firm will serve and how it will go about accomplishing its societal purpose.[752]

We would expect to see the mission statement of a political party linked to generating and allocating power for the betterment of citizens. Mission statements for universities often profess to both develop and disseminate knowledge. Courts are expected to integrate the interests and activities of citizens. Finally, business firms are expected to provide economic sustenance and material well-being.[753]

Organizations that can more effectively translate the positive character of their societal contribution into a favorable image have an advantage over firms that neglect this sense of purpose. Executives who link their firm to a desirable mission can lay claim to important motivational tools that are based on a shared sense of noble purpose. Some executives and consultants talk of a "strategic vision" which links highly desirable and socially appealing goals to the contributions a firm intends to make.[754] The first step, as shown in Mastering Management 16.1, is a clear compelling mission statement.

Organizations need to refine their societal contributions in order to target their efforts toward a particular group.[755] In the United States, for example, it is generally expected that the primary beneficiary of business firms is the stockholder. Interestingly, in Japan employees are much more important, and stockholders are considered as important as banks and other financial institutions. Although each organization may have a primary beneficiary, its mission statement may also recognize the interests of many other parties. Thus, business mission statements often include service to customers, the organization's obligations to employees, and its intention to support the community.

As managers consider how they will accomplish their firm's mission, many begin with a very clear statement of which business they are in.[756] This statement can form the basis for long-term planning and may help prevent huge organizations from diverting too many resources to peripheral areas. For some corporations, answering the question of which business they are in may yield a more detailed statement concerning their products and services. These product and service goals provide an important basis for judging the firm. Output goals define the type of business an organization is in and provide some substance to the more general aspects of mission statements.

Output goals are the goals that define the type of business an organization is in.

Historically, fewer than 10 percent of the privately owned businesses founded in a typical year can be expected to survive to their twentieth birthday.[757] The survival rate for public organizations is not much better. Even in organizations for which survival is not an immediate problem, managers seek specific types of conditions within their firms that minimize the risk of demise and promote survival. These conditions are positively stated as systems goals.

Systems goals are concerned with the conditions within the organization that are expected to increase the organization's survival potential. The list of systems goals is almost endless, since each manager and researcher links today's conditions to tomorrow's existence in a different way. For many organizations, however, the list includes growth, productivity, stability, harmony, flexibility, prestige, and human-resource maintenance. In some businesses, analysts consider market share and current profitability important systems goals. Other recent studies suggest that innovation and quality are also considered important.[758]

Systems goals are concerned with conditions within the organization that are expected to increase its survival potential.

In a very practical sense, systems goals represent short-term organizational characteristics that higher-level managers wish to promote. Systems goals often must be balanced against one another. For instance, a productivity and efficiency drive, if taken too far, may reduce the flexibility of an organization even in a downturn. For example, PepsiCo's CEO Indra Nooyi, eliminated plants and over 3,000 jobs, yet she also knows she must expand PepsiCo's operations in China.[759]

Often different parts of the organization are asked to pursue different types of systems goals. For example, higher-level managers may expect to see their production operations strive for efficiency while pressing for innovation from their R&D lab and promoting stability in their financial affairs. The relative importance of different systems goals can vary substantially across various types of organizations. Although we may expect the University of British Columbia or the University of New South Wales to emphasize prestige and innovation, few expect such businesses as Pepsi or Coke to subordinate growth and profitability to prestige. We expect to see some societal expectations and output desires used to justify the incorporation of some systems goals.

Systems goals are important to firms because they provide a road map that helps them link together various units of their organization to assure survival. Well-defined systems goals are practical and easy to understand; they focus the manager's attention on what needs to be done. Accurately stated systems goals also offer managers flexibility in devising ways to meet important targets. They can be used to balance the demands, constraints, and opportunities facing the firm. Recent research suggests incorporating integrity and ethics into the desired system goals characteristics.

The choices managers make regarding systems goals should naturally form a basis for dividing the work of the firm—a basis for developing a formal structure. In other words, to insure success, management needs to match decisions regarding what to accomplish with choices concerning an appropriate way to reach these goals.

The formal structure shows the planned configuration of positions, job duties, and the lines of authority among different parts of the enterprise.[760] The configuration selected provides the organization with specific strengths to reach toward some goals more than others. Traditionally, the formal structure of the firm has also been called the division of labor. Some still use this terminology to isolate decisions concerning formal structure from choices regarding the division of markets and/or technology. We will deal with environmental and technology issues after we discuss the structure as a foundation for managerial action. Here, we emphasize that the formal structure outlines the jobs to be done, the person(s) (in terms of position) who is (are) to perform specific activities, and the ways the total tasks of the organization are to be accomplished. In other words, the formal structure is the skeleton of the firm. See Leaders on Leadership on the structural change instituted by Irene Rosenfeld, CEO of Kraft Foods.

In larger organizations, there is a clear separation of authority and duties by hierarchical rank. That is, firms are vertically specialized. This separation represents vertical specialization, a hierarchical division of labor that distributes formal authority and establishes where and how critical decisions are to be made. This division creates a hierarchy of authority—an arrangement of work positions in order of increasing authority.[761]

The Organization Chart Organization charts are diagrams that depict the formal structures of organizations. A typical chart shows the various positions, the position holders, and the lines of authority that link them to one another.

Organization charts are diagrams that depict the formal structures of organizations.

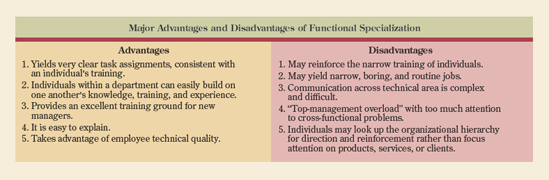

Figure 16.1 presents a partial organization chart for a large university. The total chart allows university employees to locate their positions in the structure and to identify the lines of authority linking them with others in the organization. For instance, in this figure, the treasurer reports to the vice president of administration, who, in turn, reports to the president of the university.

While an organization chart may clearly indicate who reports to whom, it is also important to recognize that it does not show how work is completed, who exercises the most power over specific issues, or how the firm will respond to its environment. An organization chart is just the beginning to an understanding of how a firm organizes its work. In firms facing constant change, the formal chart may be quickly out of date. However, organization charts can be important to the extent that they accurately represent the "chain of command."

The chain of command is a listing of who reports to whom up and down the firm and shows how executives, managers, and supervisors are hierarchically connected. Traditional management theory suggests that each individual should have one boss and each unit one leader. Under these circumstances, there is a "unity of command." Unity of command is considered necessary to avoid confusion, to assign accountability to specific individuals, and to provide clear channels of communication up and down the organization.

Span of Control The number of individuals reporting to a supervisor is called the span of control. Narrower spans of control are expected when tasks are complex, when subordinates are inexperienced or poorly trained, or when tasks call for team effort. Unfortunately, narrow spans of control yield many organizational levels. The excessive number of levels is not only expensive, but it also makes the organization unresponsive to necessary change. Communications in such firms often become less effective because they are successively screened and modified so that subtle but important changes are ignored. Furthermore, with many levels, managers are removed from the action and become isolated.

New information technologies now allow organizations to broaden the span of control, flatten their formal structures, and still maintain control of complex operations. At Nucor, for instance, senior managers pioneered the development of "minimills" for making steel and developed what they call "lean" management. At the same time, management has expanded the span of control with extensive employee education and training backed by sophisticated information systems. The result: Nucor has four levels of management from the bottom to the top.[762]

Line and Staff Units A very useful way to examine the vertical division of labor is to separate line and staff units. Line units and personnel conduct the major business of the organization. The production and marketing functions are two examples. In contrast, staff units and personnel assist the line units by providing specialized expertise and services, such as accounting and public relations. For example, the vice president of administration in a university (Figure 16.1) heads a staff unit, as does the vice president of student affairs. All academic departments are line units since they constitute the basic production function of the university.

Two additional useful distinctions regarding line and staff are often made in firms. One distinction is the nature of the relationship of a unit in the chain of command. A staff department, such as the office of the V.P. for External Affairs in Figure 16.1, may be divided into subordinate units, such as Legislative Liaison and Development. Although all units reporting to a higher-level staff unit are considered staff from an organizational perspective, some subordinate staff units are charged with conducting the major business of the higher unit—they have a line relationship up the chain of command. In Figure 16.1 both Legislative Liaison and Development are staff units with a line relationship to the unit immediately above them in the chain of command—the V.P. for External Affairs. Why the apparent confusion? It is a matter of history, with the notion of line and staff originally coming from the military with its emphasis on command. In a military sense, the V.P. for External Affairs is the commander of this staff effort—the individual responsible for this activity and the one held accountable.

A second useful distinction for both line and staff units concerns the amount and types of contacts each maintains with outsiders to the organization. Some units are mainly internal in orientation; others are more external in focus. In general, internal line units (e.g., production) focus on transforming raw materials and information into products and services, whereas external line units (e.g., marketing) focus on maintaining linkages to suppliers, distributors, and customers. Internal staff units (e.g., accounting) assist the line units in performing their function. Normally, they specialize in specific technical or financial areas. External staff units (e.g., public relations) also assist the line units, but the focus of their actions is on linking the firm to its environment and buffering internal operations. To recap: the Legislative Liaison unit is external staff with a line relationship to the office of the V.P. for External Affairs.

Staff units can be assigned predominantly to senior-, middle-, or lower-level managers. When staff is assigned predominantly to senior management, the capability of senior management to develop alternatives and make decisions is expanded. When staff is at the top, senior executives can directly develop information and alternatives and check on the implementation of their decisions. Here, the degree of vertical specialization in the firm is comparatively lower because senior managers plan, decide, and control via their centralized staff. With new information technologies, fewer firms are placing most staff at the top. They are replacing internal staff with information systems and placing talented individuals farther down the hierarchy. For instance, executives at giant international glass bottle maker OI have shifted staff from top management to middle management. When staff are moved to the middle of the organization, middle managers now have the specialized help necessary to expand their role.

Many firms are also beginning to ask whether certain staff should be a permanent part of the organization at all. Some are outsourcing many of their staff functions. Manufacturing firms are spinning off much of their accounting, personnel, and public relations activities to small, specialized firms.[763] Outsourcing by large firms has been a boon for smaller corporations.

For some time, firms have used information technology to streamline operations and reduce staff to lower costs and raise productivity.[764] One way to facilitate these actions is to provide line managers and employees with information and managerial techniques designed to expand on their analytical and decision-making capabilities—that is, to replace internal staff.[765]

When considering the firm's hierarchy, vertical specialization with its division of labor that distributes formal authority is only half of the picture. Distributing formal authority calls for control. Control is the set of mechanisms used to keep action or outputs within predetermined limits. Control deals with setting standards, measuring results versus standards, and instituting corrective action. We should stress that effective control occurs before action actually begins. For instance, in setting standards, managers must decide what will be measured and how accomplishment will be determined. While there are a wide variety of organizational controls, they are roughly divided into output, process, and social controls.

Control is the set of mechanisms used to keep actions and outputs within predetermined limits.

Output Controls Earlier in this chapter, we suggested that systems goals are a road map that ties together the various units of the organization to achieve a practical objective. Developing targets or standards, measuring results against these targets, and taking corrective action are all steps involved in developing output controls.[766] Output controls focus on desired targets and allow managers to use their own methods to reach defined targets. Most modern organizations use output controls as part of an overall method of managing by exception.

Output controls are controls that focus on desired targets and allow managers to use their own methods for reaching defined targets.

Output controls are popular because they promote flexibility and creativity and they facilitate dialogue concerning corrective actions. Reliance on outcome controls separates what is to be accomplished from how it is to be accomplished. Thus, the discussion of goals is separated from the dialogue concerning methods. This separation can facilitate the movement of power down the organization, as senior managers are reassured that individuals at all levels will be working toward the goals senior management believes are important, even as lower-level managers innovate and introduce new ways to accomplish these goals.

Process Controls Few organizations run on outcome controls alone. Once a solution to a problem is found and successfully implemented, managers do not want the problem to recur, so they institute process controls. Process controls attempt to specify the manner in which tasks are accomplished. There are many types of process controls, but three groups have received considerable attention: (1) policies, procedures, and rules; (2) formalization and standardization; and (3) total quality management controls. Before we discuss each of these, check OB Savvy 16.1 for a note of caution.

Process controls are controls that attempt to specify the manner in which tasks are to be accomplished.

Policies, Procedures, and Rules Most organizations implement a variety of policies, procedures, and rules to help specify how goals are to be accomplished. Usually, we think of a policy as a guideline for action that outlines important objectives and broadly indicates how an activity is to be performed. A policy allows for individual discretion and minor adjustments without direct clearance by a higher-level manager. Procedures indicate the best method for performing a task, show which aspects of a task are the most important, or outline how an individual is to be rewarded.

Many firms link rules and procedures. Rules are more specific, rigid, and impersonal than policies. They typically describe in detail how a task or a series of tasks is to be performed, or they indicate what cannot be done. They are designed to apply to all individuals, under specified conditions. For example, most car dealers have detailed instruction manuals for repairing a new car under warranty, and they must follow very strict procedures to obtain reimbursement from the manufacturer for warranty work.

Rules, procedures, and policies are often employed as substitutes for direct managerial supervision. Under the guidance of written rules and procedures, the organization can specifically direct the activities of many individuals. It can ensure virtually identical treatment across even distant work locations. For example, a McDonald's hamburger and fries taste much the same whether they are purchased in Hong Kong, Indianapolis, London, or Toronto simply because the ingredients and the cooking methods follow written rules and procedures.

Formalization and Standardization Formalization refers to the written documentation of rules, procedures, and policies to guide behavior and decision making. Beyond substituting for direct management supervision, formalization is often used to simplify jobs. Written instructions allow individuals with less training to perform comparatively sophisticated tasks. Written procedures may also be available to ensure that a proper sequence of tasks is executed, even if this sequence is performed only occasionally.

Formalization is the written documentation of work rules, policies, and procedures.

Most organizations have developed additional methods for dealing with recurring problems or situations. Standardization is the degree to which the range of allowable actions in a job or series of jobs is limited so that actions are performed in a uniform manner. It involves the creation of guidelines so that similar work activities are repeatedly performed in a similar fashion. Such standardized methods may come from years of experience in dealing with typical situations, or they may come from outside training. For instance, if you are late in paying your credit card, the bank will automatically send you a notification and start an internal process of monitoring your account.

Standardization is the degree to which the range of actions in a job or series of jobs is limited.

Total Quality Management The process controls discussed so far—policies, procedures, rules, formalization, and standardization—represent the lessons of experience within an organization. That is, managers institute these process controls based on experience typically one at a time. Often there is no overall philosophy for using control to improve the overall operations of the company. Another way to institute process controls is to establish a total quality management process within the firm.

The late W. Edwards Deming is the modern-day founder of the total quality management movement.[767] When Deming's ideas were not generally accepted in the United States, he found an audience in Japan. Thus, to some managers, Deming's ideas appear in the form of the best Japanese business practices.

The heart of Deming's approach is to institute a process approach to continual improvement based on statistical analyses of the firm's operations. Around this core idea, Deming built a series of 14 points for managers to implement. As they are shown in Mastering Management 16.2, note the emphasis on everyone working together using statistical controls to improve continually. All levels of management are to be involved in the quality program. Managers are to improve supervision, train employees, retrain employees in new skills, and create a structure that pushes the quality program. Where the properties of the firm's outcomes are well defined, as in most manufacturing operations, Deming's system and emphasis on quality work well, especially when implemented in conjunction with empowerment and participative management.

Different firms use very different mixes of vertical specialization, output controls, process controls, and managerial techniques to allocate the authority or discretion to act.[768] The farther up the hierarchy of authority the discretion to spend money, to hire people, and to make similar decisions is moved, the greater the degree of centralization. The more such decisions are delegated, or moved down the hierarchy of authority, the greater the degree of decentralization.

Centralization is the degree to which the authority to make decisions is restricted to higher levels of management.

Decentralization is the degree to which the authority to make decisions is given to lower levels in an organization's hierarchy.

Greater centralization is often adopted when the firm faces a single major threat to its survival. Thus, it is little wonder that armies tend to be centralized and that firms facing bankruptcy increase centralization. Recent research even suggests that governmental agencies may improve their performance via centralization when in a defensive mode.[769]

Greater decentralization generally provides higher subordinate satisfaction and a quicker response to a diverse series of unrelated problems. Decentralization also assists in the on-the-job training of subordinates for higher-level positions. Decentralization is now a popular approach in many industries. For instance, Union Carbide is pushing responsibility down the chain of command, as are SYSCO and Hewlett-Packard. In each case, the senior managers hope to improve both performance quality and organizational responsiveness. Closely related to decentralization is the notion of participation. Many people want to be involved in making decisions that affect their work. Participation results when a manager delegates some authority for such decision making to subordinates in order to include them in the choice process. Employees may want a say both in what the unit objectives should be and in how they may be achieved.[770]

Firms such as Intel Corporation, Eli Lilly, Texas Instruments, and Hoffmann-LaRoche have also experimented by moving decisions down the chain of command and increasing participation. Governmental agencies find that increasing decentralization helps them effectively explore innovations.[771] Firms have generally found that just cutting the number of organizational levels was insufficient. They also needed to alter their controls toward quality, to stress constant improvement, and to change other basic features of the organization. As these firms changed their degree of vertical specialization, they also changed the division of work among units or the firm's horizontal specialization.

Managers must divide the total task into separate duties and group similar people and resources together.[772] Organizing work is formally known as horizontal specialization. Horizontal specialization is a division of labor that establishes specific work units or groups within an organization. This aspect of the organization is also called departmentation. There are several pure forms of departmentation. Whenever managers divide tasks and group similar types of skills and resources together, they must also be concerned with how each group's individual efforts will integrate with others. Integration across the firm is the subject of coordination. As noted below, managers use a mix of personal and impersonal methods of coordination to tie the efforts of departments together.

Horizontal specialization is a division of labor through the formation of work units or groups within an organization.

Since the pattern of departmentation is so visible and important in a firm, managers often refer to their pattern of departmentation as the departmental structure. While most firms use a mix of various types of departments, it is important to look at the traditional types and what they do and do not provide the firm.

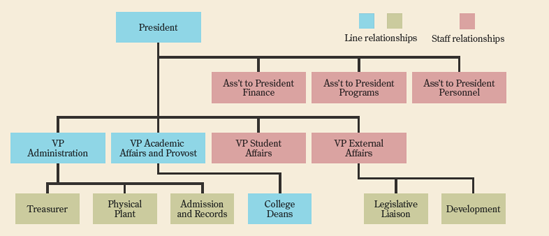

Functional Departments Grouping individuals by skill, knowledge, and action yields a pattern of functional departmentation. Recall that Figure 16.1 shows the partial organization chart for a large university in which each department has a technical specialty. Marketing, finance, production, and personnel are important functions in business. In many small firms, this functional pattern dominates. Even large firms use this pattern in technically demanding areas. Figure 16.2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the functional pattern. With all of these advantages, it is not surprising that the functional form is extremely popular. It is used in most organizations, particularly toward the bottom of the hierarchy. The extensive use of functional departments also has some disadvantages. Organizations that rely heavily on functional specialization may expect the following tendencies to emerge over time: an emphasis on quality from a technical standpoint, rigidity to change, and difficulty in coordinating the actions of different functional areas.

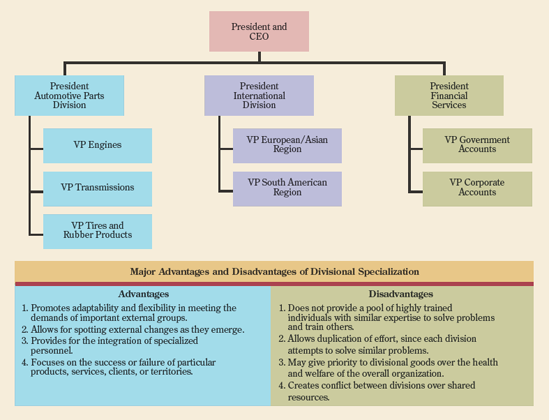

Divisional Departments In divisional departments individuals and resources are grouped by products, territories, services, clients, or legal entities.[773] Figure 16.3 shows a divisional pattern of organization grouped around products, regions, and customers for three divisions of a conglomerate. This pattern is often used to meet diverse external threats and opportunities. As shown in Figure 16.3, the major advantages of the divisional pattern are its flexibility in meeting external demands, spotting external changes, integrating specialized individuals deep within the organization, and focusing on the delivery of specific products to specific customers. Among its disadvantages are duplication of effort by function, the tendency for divisional goals to be placed above corporate interests, and conflict among divisions. It is also not the structure most desired for training individuals in technical areas; firms relying on this pattern may fall behind technically to competitors with a functional pattern.

Many larger, geographically dispersed organizations that sell to national and international markets may rely on departmentation by geography. The savings in time, effort, and travel can be substantial, and each territory can adjust to regional differences. Organizations that rely on a few major customers may organize their people and resources by client. Here, the idea is to focus attention on the needs of the individual customer. To the extent that customer needs are unique, departmentation by customer can also reduce confusion and increase synergy. Organizations expanding internationally may also form divisions to meet the demands of complex host-country ownership requirements. For example, NEC, Sony, Nissan, and many other Japanese corporations have developed U.S. divisional subsidiaries to service their customers in the U.S. market. Some huge European-based corporations such as Philips and Nestlé have also adopted a divisional structure in their expansion to the United States. Similarly, most of the internationalized U.S.-based firms, such as IBM, GE, and DuPont, have incorporated the divisional structure as part of their internalization programs.

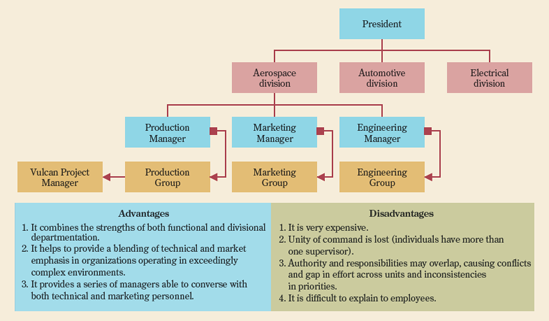

Matrix Structures Originally from the aerospace industry, a third unique form of departmentation called the matrix structure was developed and is now becoming more popular.[774] In aerospace efforts, projects are technically very complex, involving hundreds of subcontractors located throughout the world. Precise integration and control are needed across many sophisticated functional specialties and corporations. This is often more than a functional or divisional structure can provide, for many firms do not want to trade the responsiveness of the divisional form for the technical emphasis provided by the functional form. Thus, matrix departmentation uses both the functional and divisional forms simultaneously. Figure 16.4 shows the basic matrix arrangement for an aerospace program. Note the functional departments on one side and the project efforts on the other. Workers and supervisors in the middle of the matrix have two bosses—one functional and one project.

Matrix departmentation is a combination of functional and divisional patterns wherein an individual is assigned to more than one type of unit.

The major advantages and disadvantages of the matrix form of departmentation are summarized in Figure 16.4. The key disadvantage of the matrix method is the loss of unity of command. Individuals can be unsure as to what their jobs are, whom they report to for specific activities, and how various managers are to administer the effort. It can also be a very expensive method because it relies on individual managers to coordinate efforts deep within the firm. Despite these limitations, the matrix structure provides a balance between functional and divisional concerns. Many problems can be resolved at the working level, where the balance among technical, cost, customer, and organizational concerns can be dealt with.

NBBJ, the world's third largest architectural practice, manages a very broad range of projects. To meet these diverse challenges, NBBJ uses a matrix structure to draw specialists from its global offices to complete major design projects. NBBJ executives use senior contact staff in a local design studio to identify and focus on the specific needs of a client. They matrix across the global locations to supplement a local studio's staff.[775] Many organizations also use elements of the matrix structure without officially using the term matrix. For example, special project teams, coordinating committees, and task forces can be the beginnings of a matrix. These temporary structures can be used within a predominantly functional or divisional form and without upsetting the unity of command or hiring additional managers.

Which form of departmentation should be used? As the matrix concept suggests, it is possible to departmentalize by two different methods at the same time. Actually, organizations often use a mixture of departmentation forms. It is often desirable to divide the effort (group people and resources) by two methods at the same time in order to balance the advantages and disadvantages of each. These mixed forms help firms use their division of labor to capitalize on environmental opportunities, capture the benefits of larger size, and realize the potential of new technologies in pursuit of its strategy.

Whatever is divided up horizontally in two departments must also be integrated.[776] Coordination is the set of mechanisms that an organization uses to link the actions of their units into a consistent pattern. This linkage includes mechanisms to link managers and staff units, operating units with each other, and divisions with each other. Coordination is needed at all levels of management, not just across a few scattered units. Much of the coordination within a unit is handled by its manager. Smaller organizations may rely on their management hierarchy to provide the necessary consistency and integration. As the organization grows, however, managers become overloaded. The organization then needs to develop more efficient and effective ways of linking work units to one another.

Coordination is the set of mechanisms used in an organization to link the actions of its subunits into a consistent pattern.

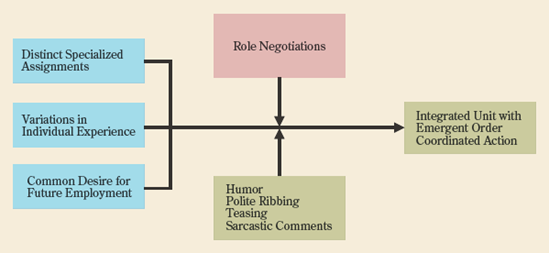

Personal Methods of Coordination Personal methods of coordination produce synergy by promoting dialogue and discussion, innovation, creativity, and learning, both within and across organizational units. Personal methods allow the organization to address the particular needs of distinct units and individuals simultaneously. There is a wide variety of personal methods of coordination.[777] Perhaps the most popular is direct contact between and among organizational members. As new information technologies have moved into practice, the potential for developing and maintaining effective contact networks has expanded. For example, many executives use e-mail to supplement direct personal communication. Direct personal contact is also associated with the ever-present "grapevine." Although the grapevine is notoriously inaccurate in its role as the corporate rumor mill, it is often both accurate enough and quick enough that managers cannot ignore it. Instead, managers need to work with and supplement the rumor mill with accurate information.

Managers are often assigned to numerous committees to improve coordination across departments. Even though committees are generally expensive and have a very poor reputation, they can become an effective personal mechanism for mutual adjustment across unit heads. Committees can be effective in communicating complex qualitative information and in helping managers whose units must work together to adjust schedules, workloads, and work assignments to increase productivity. As more organizations develop flatter structures with greater delegation, they are finding that task forces can be quite useful. Whereas committees tend to be long lasting, task forces are typically formed with a more limited agenda. Individuals from different parts of the organization are assembled into a task force to identify and solve problems that cut across different departments.

No magic is involved in selecting the appropriate mix of personal coordination methods and tailoring them to the individual skills, abilities, and experience of subordinates. Managers need to know the individuals involved, their preferences, and the accepted approaches in different organizational units. As the Research Insights feature suggests, different personal methods can be tailored to match different individuals and the settings in which they operate. Personal methods are only one important part of coordination. The manager may also establish a series of impersonal mechanisms.

Impersonal Methods of Coordination Impersonal methods of coordination produce synergy by stressing consistency and standardization so that individual pieces fit together. Impersonal coordination methods are often refinements and extensions of process controls with an emphasis on formalization and standardization. Larger organizations often have written policies and procedures, such as schedules, budgets, and plans that are designed to mesh the operations of several units into a whole by providing predictability and consistency.

Historically, firms used specialized departments to coordinate across units. However, this method is very expensive and often results in considerable rigidity. The most highly developed form of impersonal coordination comes with the adoption of a matrix structure. As noted earlier, this form of departmentation is designed to coordinate the efforts of diverse functional units. Many firms are using cross-functional task forces instead of maintaining specialized departments or implementing a matrix.

The final example of impersonal coordination mechanisms is undergoing radical change in many modern organizations. Originally, management information systems were developed and designed so that senior managers could coordinate and control the operations of diverse subordinate units. These systems were intended to be computerized substitutes for schedules, budgets, and the like. In some firms, the management information system still operates as a combined process control and impersonal coordination mechanism. In the hands of astute managers, however, the management information system becomes an electronic network, linking individuals throughout the organization. Using decentralized communication systems that connect all members allows once centralized systems to evolve into a supplement to personal coordination.

In the United States there is an aversion to controls, as the culture prizes individuality, democracy, and individual free will. Managers often institute controls under the title of coordination. Since some of the techniques are used for both, many managers suggest that all efforts at control are for coordination. It is extremely important to separate these two functions simply because the reactions to controls and coordination are quite different. The underlying logic of control involves setting targets, measuring performance, and taking corrective action to meet goals normally assigned by higher management. Thus, many employees see an increase in controls as a threat based on a presumption that they have been doing something wrong. The logic of coordination is to get unit actions and interactions meshed together into a unified whole. While control involves the vertical exercise of formal authority involving targets, measures, and corrective action, coordination stresses cooperative problem solving. Experienced employees recognize the difference between controls and coordination regardless of what the boss calls it.[778] Increasing controls rarely solves problems of coordination, and emphasizing coordination to solve control issues rarely works.

In the developed world, most firms are bureaucracies. In OB this term has a very special meaning, beyond its negative connotation. The famous German sociologist Max Weber suggested that organizations would thrive if they became bureaucracies by emphasizing legal authority, logic, and order.[779] Ideally, bureaucracies rely on a division of labor, hierarchical control, promotion by merit with career opportunities for employees, and administration by rule.

Bureaucracy is an ideal form of organization, the characteristics of which were defined by the German sociologist Max Weber.

Weber argued that the rational and logical idea of bureaucracy was superior to building the firm based on charisma or cultural tradition. The "charismatic" ideal-type organization was overly reliant on the talents of one individual and could fail when the leader leaves. Too much reliance on cultural traditions blocked innovation, stifled efficiency, and was often unfair. Since the bureaucracy prizes efficiency, order, and logic, Weber hoped that it could also be fair to employees and provide more freedom for individual expression than is allowed when tradition dominates or dictators rule. Many interpreted Weber as suggesting that bureaucracy or some variation of this ideal form, although far from perfect, would dominate modern society.[780] For large organizations the bureaucratic form is predominant. Yet, as noted in OB Savvy 16.2, this comes at some costs as well. While charismatic leadership and cultural traditions are still important today, it is the rational, legal, and efficiency aspects of the firm that characterize modern corporations.

Just as interpretations of Weber have evolved over time, so has the notion of a bureaucracy.[781] We will discuss two popular basic types of bureaucracies: the mechanistic structure and machine bureaucracy and the organic structure and professional bureaucracy as well as some hybrid approaches. Each type is a different mix of the basic elements discussed in this chapter, and each mix yields firms with a slightly different blend of capabilities and natural tendencies. That is, each type of bureaucracy allows the firm to pursue some goals more easily than others.

Mechanistic type of machine bureaucracy emphasizes vertical specialization and control with impersonal coordination and a heavy reliance on standardization, formalization, rules, policies, and procedures.

The mechanistic type of bureaucracy emphasizes vertical specialization and control.[782] Organizations of this type stress rules, policies, and procedures; specify techniques for decision making; and emphasize developing well-documented control systems backed by a strong middle management and supported by a centralized staff. There is often extensive use of the functional pattern of departmentation throughout the firm. Henry Mintzberg uses the term machine bureaucracy to describe an organization structured in this manner.[783]

The mechanistic design results in a management emphasis on routine for efficiency. Firms often used this design in pursuing a strategy of becoming a low-cost leader. Until the implementation of new information systems, most large-scale firms in basic industries were machine bureaucracies. Included in this long list were all of the auto firms, banks, insurance companies, steel mills, large retail establishments, and government offices. Efficiency was achieved through extensive vertical and horizontal specialization tied together with elaborate controls and impersonal coordination mechanisms.

There are, however, limits to the benefits of specialization backed by rigid controls. Employees do not like rigid designs, so motivation becomes a problem. Unions further solidify narrow job descriptions by demanding fixed work rules and regulations to protect employees from the extensive vertical controls. Key employees may leave. In short, using a machine bureaucracy can hinder an organization's capacity to adjust to subtle external changes or new technologies.

The organic type is much less vertically oriented than its mechanistic counterpart is; it emphasizes horizontal specialization. Procedures are minimal, and those that do exist are not as formalized. The organization relies on the judgments of experts and personal means of coordination. When controls are used, they tend to back up professional socialization, training, and individual reinforcement. Staff units are placed toward the middle of the organization. Because this is a popular design in professional firms, Mintzberg calls it a professional bureaucracy.[784]

Organic type or professional bureaucracy emphasizes horizontal specialization, extensive use of personal coordination, and loose rules, policies, and procedures.

Your university is probably a professional bureaucracy that looks like a broad, flat pyramid with a large bulge in the center for the professional staff. Power in this ideal type rests with knowledge. Furthermore, there was often an elaborate staff to "help" the line managers. Often the staff had very little formal power, other than to block action. Control is enhanced by the standardization of professional skills and the adoption of professional routines, standards, and procedures. Other examples of organic types include most hospitals and social service agencies.

Although not as efficient as the machine bureaucracy, the professional bureaucracy is better for problem solving and for serving individual customer needs. Since lateral relations and coordination are emphasized, centralized direction by senior management is less intense. Thus, this type is good at detecting external changes and adjusting to new technologies, but at the sacrifice of responding to central management direction.[785] Firms using this pattern found it easier to pursue product quality, quick response to customers, and innovation as strategies.

Many very large firms found that neither the mechanistic nor the organic approach was suitable for all of their operations. Adopting a machine bureaucracy would overload senior management and yield too many levels of management. Yet, adopting an organic type would mean losing control and becoming too inefficient. Senior managers may opt for one of a number of hybrid types.

We have already briefly introduced two of the more common hybrid types. One is an extension of the divisional pattern of departmentation, and sometimes called a divisional firm. Here, the firm is composed of quasi-independent divisions so that different divisions can be more or less organic or mechanistic. While the divisions may be treated as separate businesses, they often share a similar mission and systems goals.[786] When adopting this hybrid type, each division can pursue a different strategy. Land O' Lakes, for instance, is a divisional cooperative.

A second hybrid is the true conglomerate. A conglomerate is a single corporation that contains a number of unrelated businesses. On the surface, these firms look like divisionalized firms, but when the various businesses of the divisions are unrelated, the term conglomerate is applied.[787] For instance, General Electric is a conglomerate that has divisions in unrelated businesses and industries, ranging from producing light bulbs, to designing and servicing nuclear reactors, to building jet engines, to operating the National Broadcasting Company. Many state and federal entities are also, by necessity, conglomerates. For instance, a state governor is the chief executive officer of those units concerned with higher education, welfare, prisons, highway construction and maintenance, police, and the like.

The conglomerate type also simultaneously illustrates three important points. (1) All structures are combinations of the basic elements. (2) There is no one best structure—it all depends on a number of factors such as the size of the firm, its environment, its technology, and, of course, its strategy. (3) The firm does not stand alone but is part of a larger network of firms that competes against other networks.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 16.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 16 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What are the different types of organizational goals?

Societal goals: organizations make specific contributions to society and gain legitimacy from these contributions.

A societal contribution focused on a primary beneficiary may be represented in the firm's mission statement.

Output goals: as managers consider how they will accomplish their firm's mission, many begin with a very clear statement of which business they are in.

Firms often specify output goals by detailing the types of specific products and services they offer.

Systems goals: corporations have systems goals to show the conditions managers believe will yield survival and success.

Growth, productivity, stability, harmony, flexibility, prestige, and human-resource maintenance are examples of systems goals.

What are the hierarchical aspects of organizations?

The formal structure is also known as the firm's division of labor.

The formal structure defines the intended configuration of positions, job duties, and lines of authority among different parts of the enterprise.

Vertical specialization is used to allocate formal authority within the organization and may be seen on an organization chart.

Vertical specialization is the hierarchical division of labor that specifies where formal authority is located.

Typically, a chain of command exists to link lower-level workers with senior managers.

The distinction between line and staff units also indicates how authority is distributed, with line units conducting the major business of the firm and staff providing support.

Managerial techniques, such as decision support and expert computer systems, are used to expand the analytical reach and decision-making capacity of managers to minimize staff.

Control is the set of mechanisms the organization uses to keep action or outputs within predetermined levels.

Output controls focus on desired targets and allow managers to use their own methods for reaching these targets.

Process controls specify the manner in which tasks are to be accomplished through (1) policies, rules, and procedures; (2) formalization and standardization; and (3) total quality management processes.

Firms are learning that decentralization often provides substantial benefits.

How is work organized and coordinated?

Horizontal specialization is the division of labor that results in various work units and departments in the organization.

Three main types or patterns of departmentation are observed: functional, divisional, and matrix. Each pattern has a mix of advantages and disadvantages.

Organizations may successfully use any type, or a mixture, as long as the strengths of the structure match the needs of the organization.

Coordination is the set of mechanisms an organization uses to link the actions of separate units into a consistent pattern.

Personal methods of coordination produce synergy by promoting dialogue, discussion, innovation, creativity, and learning.

Impersonal methods of control produce synergy by stressing consistency and standardization so that individual pieces fit together.

What are bureaucracies and what are the common forms?

The bureaucracy is an ideal form based on legal authority, logic, and order that provides superior efficiency and effectiveness.

Mechanistic, organic, and hybrid are common types of bureaucracies.

Hybrid types include the divisionalized firm and the conglomerate. No one type is always superior to the others.

Bureaucracy (p. 407)

Centralization (p. 399)

Conglomerates (p. 409)

Control (p. 397)

Coordination (p. 404)

Decentralization (p. 399)

Divisional departmentation (p. 401)

Formalization (p. 398)

Functional departmentation (p. 400)

Horizontal specialization (p. 400)

Line units (p. 396)

Matrix departmentation (p. 402)

Mechanistic type or machine bureaucracy (p. 407)

Mission statements (p. 390)

Organic type or professional bureaucracy (p. 408)

Organization charts (p. 393)

Output controls (p. 397)

Output goals (p. 392)

Process controls (p. 397)

Societal goals (p. 390)

Span of control (p. 395)

Staff units (p. 396)

Standardization (p. 398)

Systems goals (p. 392)

Vertical specialization (p. 393)

The major types of goals for most organizations are ____________. (a) societal, personal, and output (b) societal, output and systems (c) personal and impersonal (d) profits, corporate responsibility, and personal (e) none of the above

The formal structures of organizations may be shown in a(n) ____________. (a) environmental diagram (b) organization chart (c) horizontal diagram (d) matrix depiction (e) labor assignment chart

A major distinction between line and staff units concerns ____________. (a) the amount of resources each is allowed to utilize (b) linkage of their jobs to the goals of the firm (c) the amount of education or training they possess (d) their use of computer information systems (e) their linkage to the outside world

The division of labor by grouping people and material resources deals with ____________. (a) specialization (b) coordination (c) divisionalization (d) vertical specialization (e) goal setting

Control involves all but ____________. (a) measuring results (b) establishing goals (c) taking corrective action (d) comparing results with goals (e) selecting manpower

Grouping individuals and resources in the organization around products, services, clients, territories, or legal entities is an example of ____________ specialization. (a) divisional (b) functional (c) matrix (d) mixed form (e) outsourced specialization

Grouping resources into departments by skill, knowledge, and action is the ____________ pattern. (a) functional (b) divisional (c) vertical (d) means-end chains (e) matrix

A matrix structure ____________. (a) reinforces unity of command (b) is inexpensive (c) is easy to explain to employees (d) gives some employees two bosses (e) yields a minimum of organizational politics

____________ is the concern for proper communication enabling the units to understand one another's activities. (a) Control (b) Coordination (c) Specialization (d) Departmentation (e) Division of Labor

Compared to the machine bureaucracy (mechanistic type), the professional bureaucracy (organic type) ____________. (a) is more efficient for routine operations (b) has more vertical specialization and control (c) is larger (d) has more horizontal specialization and coordination mechanism (e) is smaller

Written statements of organizational purpose are called ____________. (a) mission statements (b) formalization (c) mean-ends chains (d) formalization

____________ is grouping individuals by skill, knowledge, and action yields. (a) Divisional departmentation (b) Functional departmentation (c) Hybrid structuration (d) Matrix departmentation

The division of labor through the formation of work units or groups within an organization is called ____________. (a) control (b) vertical specialization (c) horizontal specialization (d) coordination

______________ is the set of mechanisms used in an organization to link the actions of its subunits into a consistent pattern. (a) Departmentation (b) Coordination (c) Control (d) Formal authority

The set of mechanisms used to keep actions and outputs within predetermined limits is called ____________. (a) coordination (b) vertical specialization (c) control (d) formalization

__________________ describes how formal authority is distributed and establishes where and how critical decisions are to be made. (a) Vertical/horizontal specialization (b) Centralization/decentralization (c) Control/coordination (d) Bureaucratic/charismatic

Grouping people together by skill, knowledge, and action yields a ________ pattern of departmentation. (a) functional (b) divisional (c) matrix (d) dispersed

____________ in an organization provide specialized expertise and services. (a) Staff units and personnel (b) Line units and personnel (c) Cross-functional teams (d) Auditing units

One of the advantages of a ______________ is that it helps provide a blending of technical and market emphases in organizations operating in exceedingly complex environments. (a) functional structure (b) matrix structure (c) divisional structure (d) conglomerate structure

_________ goals are the goals that define the type of business an organization is in. (a) Divisional (b) Systems (c) Societal (d) Output

Compare and contrast output goals with systems goals.

Describe the types of controls that are used in organizations.

What are the major advantages and disadvantages of functional departmentation?

What are the major advantages and disadvantages of matrix departmentation?