chapter at a glance

In our busy multi-tasking world where work, family, and leisure are often intertwined, there's much to consider when trying to build high-performance work settings that also fit well with individual needs and goals. Here's what to look for in Chapter 6. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT IS THE LINK BETWEEN MOTIVATION, PERFORMANCE, AND REWARDS?

Integrated Model of Motivation

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards

Pay for Performance

Pay for Skills

WHAT ARE THE ESSENTIALS OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT?

Performance Management Process

Performance Appraisal Methods

Performance Appraisal Errors

HOW DO JOB DESIGNS INFLUENCE MOTIVATION AND PERFORMANCE?

Scientific Management

Job Enlargement and Job Rotation

Job Enrichment

Job Characteristics Model

WHAT ARE THE MOTIVATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES OF ALTERNATIVE WORK ARRANGEMENTS?

Compressed Work Weeks

Flexible Working Hours

Job Sharing

Telecommuting

Part-Time Work

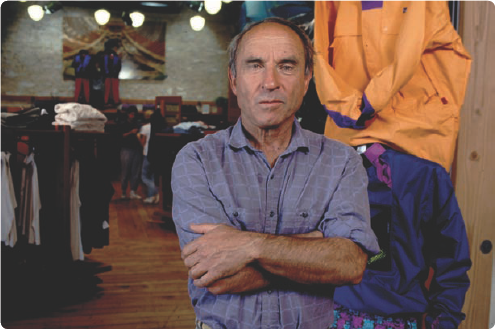

Would you buy into this vision: high-quality products and minimum impact on the environment? Workers at the outdoor clothing supplier Patagonia Inc. do. Says one MBA who turned down a job with a global giant to start as a stock handler at one of the firm's California stores: "I wanted to work for a company that's driven by values." And those values driving Patagonia begin with the founder, Yvon Chouinard. "Most people want to do good things but don't. At Patagonia," he says, "it's an essential part of your life." The firm's stated mission is: "Build the best product, do no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire, and implement solutions to the environmental crisis." And Chouinard understands that it all happens through people.

Stop into its headquarters in Ventura, California, and you will find on-site day care and full medical benefits for all employees—full-time and part-time alike. In return, Chouinard expects the best: hard work and high performance achieved through creativity and collaboration. And he refuses to grow the firm too fast, preferring to keep things manageable so that values and vision are well served.

"It's easy to go to work when you get paid to do what you love to do."

At a time when polls report that many Americans are losing or feeling less passion for their jobs because of high stress, bad bosses, and jobs lacking in motivational pull, Patagonia offers something different. Although employees are well paid and get the latest in bonus packages, the firm doesn't focus on money as the top reward. Its most popular perk is the "green sabbatical"—time off, with pay, to work for environmental causes. Says one of those who succeeded in landing a job where there are 900 resumes for every open position: "It's easy to go to work when you get paid to do what you love to do."

Chouinard describes his approach to running a business in his book, Let My People Go Surfing. It is a green-business primer and memoir. Patagonia has reused materials and, among other things, provided on-site day care, flextime, and maternity and paternity leave. The guiding philosophy has given priority to doing things right and profits will follow. So far it's working; Patagonia is now a $270+ million business

it's about person-job fit

Wouldn't it be nice if we could all connect with our jobs and organizations the way those at Patagonia seem to do? In fact there are lots of great workplaces out there, and they become great because the managers at all levels of responsibility do things that end up turning people on to their work rather than off of it. This book is full of insights and ideas in this regard, and the motivation theories discussed in the last chapter are an important part of the story. In many ways the link between theory and application rests with a manager's abilities to activate rewards so that the work environment offers motivational opportunities to people in all the rich diversity of their individual differences.

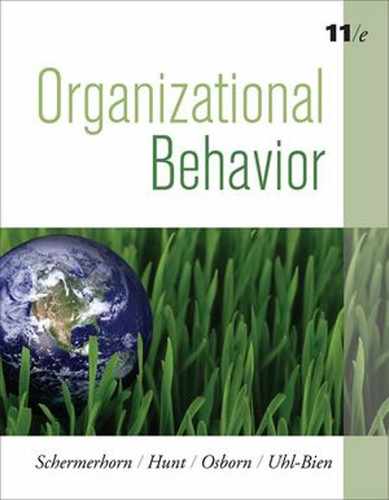

Figure 6.1 outlines an integrated model of motivation, one that ties together much of the previous discussion regarding the basic effort → performance → rewards relationship. Note that the figure shows job performance and satisfaction as separate but potentially interdependent work results. Performance is influenced most directly by individual attributes such as ability and experience; organizational support such as resources and technology; and effort, or the willingness of someone to work hard at what they are doing. Satisfaction results when rewards received for work accomplishments are performance contingent and perceived as equitable.

It is in respect to effort that an individual's level of motivation is of key importance. In the last chapter motivation was defined as forces that account for the level and persistence of an individual's effort expended at work. In other words and as shown in the figure, motivation predicts effort. But since motivation is a property of the individual, all that managers can do is try to create work environments within which someone finds sources of motivation. As the theories in the last chapter suggest, a major key to achieving this is to build into the job and work setting a set of rewards that match well with individual needs and goals.

Motivation accounts for the level and persistence of a person's effort expended at work.

Double check Figure 6.1 and locate where various motivation theories come into play. Reinforcement theory is found in the importance of performance contingency and immediacy in determining how rewards affect future performance. Equity theory is an issue in the perceived fairness of rewards. The content theories are useful guides to understanding individual needs that give motivational value to the possible rewards. And expectancy theory is central to the effort → performance → reward linkage.

The typical reward systems of organizations emphasize a mix of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Intrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that the individual receives directly as a result of task performance; they do not require the participation of another person or source. It was intrinsic rewards that were largely behind Herzberg's concept of job enrichment discussed in the last chapter. He believes that people are turned on and motivated by high content jobs that are rich in intrinsic rewards. A feeling of achievement after completing a particularly challenging task in a job designed with a good person-job fit is an example.

Intrinsic rewards are valued outcomes received directly through task performance.

Extrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that are given to an individual or group by some other person or source in the work setting. They might include things like sincere praise for a job well done or symbolic tokens of accomplishment such as "employee-of-the-month" awards. Importantly too, anything dealing with compensation, or the pay and benefits one receives at work, is an extrinsic reward. And, like all extrinsic rewards, pay and benefits have to be well managed in all aspects of the integrated model for their motivational value to prove positive in terms of performance impact.

Pay is the most obvious and perhaps most talked about extrinsic reward for many of us. And it is not only an important extrinsic reward; it is an especially complex one. When pay functions well in the context of the integrated model of motivation, it can help an organization attract and retain highly capable workers. It can also help satisfy and motivate these workers to work hard to achieve high performance. But when something goes wrong with pay, the results may well be negative effects on satisfaction and performance. Pay dissatisfaction is often reflected in bad attitudes, increased absenteeism, intentions to leave and actual turnover, poor organizational citizenship, and even adverse impacts on employees' physical and mental health.

The research of scholar and consultant Edward Lawler generally concludes that for pay to serve as a motivator, high levels of job performance must be viewed as the path through which high pay can be achieved.[321] This is the essence of performance-contingent pay or pay for performance. It basically means that you earn more when you produce more and earn less when you produce less. Although the concept is compelling, a survey by the Hudson Institute demonstrates that it is more easily said than done. When asked if employees who do perform better really get paid more, a sample of managers responded with 48 percent agreement while only 31 percent of nonmanagers indicated agreement. And when asked if their last pay raise had been based on performance, 46 percent of managers and just 29 percent of nonmanagers said yes.[322]

The essence of performance-contingent pay is that you earn more when you produce more and earn less when you produce less.

Merit Pay It is most common to talk about pay for performance in respect to merit pay, a compensation system that directly ties an individual's salary or wage increase to measures of performance accomplishments during a specified time period. Although research supports the logic and theoretical benefits of merit pay, it also indicates that the implementation of merit pay plans is not as universal or as easy as might be expected. In fact, surveys over the past 30 or so years have found that as many as 80 percent of respondents felt that they were not rewarded for a job well done.[323]

To work well, a merit pay plan should create a belief among employees that the way to achieve high pay is to perform at high levels. This means that the merit system should be based on realistic and accurate measures of individual work performance. It also means that the merit system is able to clearly discriminate between high and low performers in the amount of pay increases awarded. Finally, it is also important that any "merit" aspects of a pay increase are not confused with across-the-board "cost-of-living" adjustments.

Merit pay is also subject to criticisms. For example, merit pay plans may cause problems when they emphasize individual achievements and fail to recognize the high degree of task interdependence that is common in many organizations today. Also, merit pay systems must be consistent with overall organization strategies and environmental challenges if they are to be effective. For example, a firm facing a tight labor market with a limited supply of highly skilled individuals might benefit more from a pay system that emphasizes employee retention rather than strict performance results.[324] With these points in mind, it is appropriate to examine a variety of additional and creative pay practices.[325]

Bonuses The awarding of cash bonuses, or extra pay for performance that meets certain benchmarks or is above expectations, has been a common practice for many employers. It is especially common in the higher executive ranks. Top managers in some industries earn annual bonuses of 50 percent or more of their base salaries. One of the trends now emerging is the attempt to extend such opportunities to employees at lower levels in organizations, and in both managerial and nonmanagerial jobs. Employees at Applebee's, for example, may earn "Applebucks"—small cash bonuses that are given to reward performance and increase loyalty to the firm.[326]

Gain Sharing and Profit Sharing Another way to link pay with performance accomplishments is through gain sharing. Such a plan gives workers the opportunity to earn more by receiving shares of any productivity gains that they help to create. The Scanlon Plan is probably the oldest and best-known gain-sharing plan. It gives workers monetary rewards tied directly to specific measures of increased organizational productivity. Participation in gain sharing is supposed to create a greater sense of personal responsibility for organizational performance improvements and increase motivation to work hard. They are also supposed to encourage cooperation and teamwork in the workplace.[327]

Profit sharing is somewhat similar to gain sharing, but instead of rewarding employees for specific productivity gains they are rewarded for increased organizational profits; the more profits made, the more money that is available for distribution to employees through profit sharing.[328] Of course when profits are lower, individuals earn less due to reduced profit-sharing returns. And indeed, one of the criticisms of the approach is that profit increases and decreases are not always a direct result of employees' efforts; many other factors, including the bad global economy recently experienced, can come into play. In such cases the question becomes whether it is right or wrong for workers to earn less because of things over which they have no control.

Stock Options and Employee Ownership Another way to link pay and performance is for a company to offer its employees stock options linked to their base pay.[329] Such options give the owner the right to buy shares of stock at a future date at a fixed or "strike" price. This means that they gain financially the more the stock price rises above the original option price. The expectation is that employees with stock options will be highly motivated to do their best so that the firm performs well; they gain financially as the stock price increases. However, as the recent economic downturn reminded us, the value of the options an employee holds can decline or zero out when the stock price falls.

In employee stock ownership plans, or ESOPs, companies may give stock to employees or allow stock to be purchased by them at a price below market value. The incentive value of the stock awards or purchases is like the stock options; "employee owners" will be motivated to work hard so that the organization will perform well, its stock price will rise, and as owners they will benefit from the gains. Of course, the company's stock prices can fall as well as rise.[330] During the economic crisis many people who had invested heavily in their employer's stock were hurt substantially. Such risk must be considered in respect to the motivational value of stock options and employee ownership plans.

An alternative to pay for performance is to pay people according to the skills they possess and continue to develop. Skill-based pay rewards people for acquiring and developing job-relevant skills. Pay systems of this sort pay people for the mix and depth of skills they possess, not for the particular job assignment they hold. An example is the cross-functional team approach at Monsanto-Benevia, where each team member has developed quality, safety, administrative, maintenance, coaching, and team leadership skills. In most cases, these skills involve the use of high-tech, automated equipment. Workers are paid for this "breadth" of capability as well as for their willingness to use any of the skills needed by the company.

Skill-based pay rewards people for acquiring and developing job-relevant skills.

Skill-based pay is one of the fastest-growing pay innovations in the United States. Besides flexibility, some advantages of skill-based pay are employee cross-training—workers learn to do one another's jobs; fewer supervisors—workers can provide more of these functions themselves; and more individual control over compensation—workers know in advance what is required to receive a pay raise. One disadvantage is possible higher pay and training costs that are not offset by greater productivity. Another is the possible difficulty of deciding on appropriate monetary values for each skill.[331]

If you want to get hired by Procter & Gamble and make it to the upper management levels you better be good. Not only is the company highly selective in hiring, it also carefully tracks the performance of every manager in every job they are asked to do. The firm always has at least three performance-proven replacements ready to fill any vacancy that occurs. And by linking performance to career advancement, motivation to work hard is built into the P&G management model.[332]

The effort → performance → reward relationship is evident in the P&G management approach. However, we shouldn't underestimate the challenge of managing any such performance-based reward system. It entails responsibility for accurately measuring performance and then correctly using those measurements in making pay and other human resource management decisions. Performance must be measured in ways that are accurate and respected by everyone involved. When the performance measurement fails, the motivational value of any pay or reward systems will fail as well.

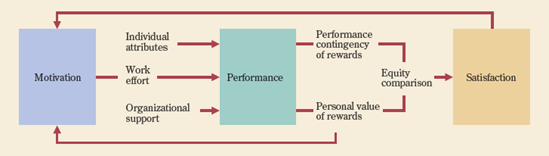

As described in Figure 6.2, performance management involves this sequence of steps: (1) identify and set clear and measurable performance goals, (2) take performance measurements to monitor goal progress, (3) provide feedback and coaching on performance results, and (4) use performance assessment for human resource management decisions such as pay, promotions, transfers, terminations, training, and career development.

The foundation for any performance management system is performance measurement. And if performance measurement is to be done well, managers must have good answers to both the "Why?" and the "What?" questions.

The "Why?" question in performance management addresses purpose, which is two-fold. Performance management serves an evaluation purpose when it lets people know where their actual performance stands relative to objectives and standards. Such an evaluation also becomes a key input to decisions that allocate rewards and otherwise administer the organization's human resource management systems. Performance management serves a developmental purpose when it provides insights into individual strengths and weaknesses that can be used to plan helpful training and career development activities.

The "What?" question in performance management takes us back to the old adage "what gets measured happens." It basically argues that people will do what they know is going to be measured. Given this, managers are well advised to always make sure they are measuring the right things in the right ways in the performance management process. Measurements should be based on clear job performance criteria, be accurate in assessing performance, provide a defensible basis for differentiating between high and low performance, and be an insightful source of feedback that can help improve performance in the future. Both output measures and activity measures are in common use.

Output measures of performance assess what is accomplished in respect to concrete work results. For example, a software developer might be measured on the number of lines of code written a day or on the number of lines written that require no corrections upon testing. Activity measures of performance assess work inputs in respect to activities tried and efforts expended. These are often used when output measures are difficult and in cases where certain activities are known to be good predictors of eventual performance success. An example might be the use of number of customer visits made per day by a sales person, instead of or in addition to counting the number of actual sales made.

Output measures of performance assess achievements in terms of actual work results.

Activity measures of performance assess inputs in terms of work efforts.

The formal procedure for measuring and documenting a person's work performance is called performance appraisal. As might be expected, there are a variety of alternative performance appraisal methods, and they each have strengths and weaknesses that make them more appropriate for use in some situations than others.[333]

Comparative Methods Comparative methods of performance appraisal seek to identify one worker's standing relative to others. Ranking is the simplest approach and is done by rank ordering each individual from best to worst on overall performance or on specific performance dimensions. Although relatively simple to use, this method can become burdensome when there are many people to consider. An alternative is the paired comparison in which each person is directly compared with every other person being rated. Each person's final ranking is determined by the number of pairs for which they emerged the "winner." As you might expect, this method gets quite complicated when there are many people to compare.

Another alternative is forced distribution. This method forces a set percentage of all persons being evaluated into pre-determined performance categories such as outstanding, good, average, and poor. For example, it might be that a team leader must assign 10 percent of members to "outstanding," another 10 percent to "poor," and another 40 percent each to "good" and "average." This forces the rater to use all the categories and avoid tendencies to rate everyone about the same. But it can be a problem if most of the people being rated are truly about the same.

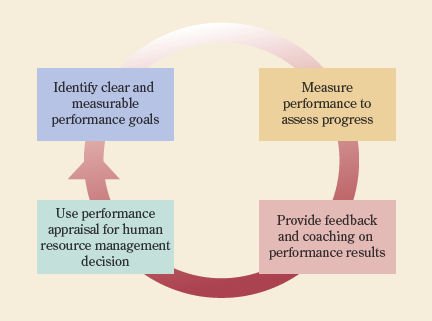

Rating Scales Graphic rating scales list a variety of dimensions that are thought to be related to high-performance outcomes for a given job that the individual is accordingly expected to exhibit, including cooperation, initiative, and attendance. The scales allow the manager to assign the individual scores on each dimension. An example is shown in Figure 6.3. These ratings are sometimes given point values and combined into numerical ratings of performance.

The primary appeal of graphic rating scales is their ease of use. They are efficient in the use of time and other resources, and they can be applied to a wide range of jobs. Unfortunately, because of generality, they may not be linked to job analysis or to other specific aspects of a given job. This difficulty can be dealt with by ensuring that only relevant dimensions of work based on sound job analysis procedures are rated. However, there is a trade-off: the more the scales are linked to job analyses, the less general they are when comparing people on different jobs.

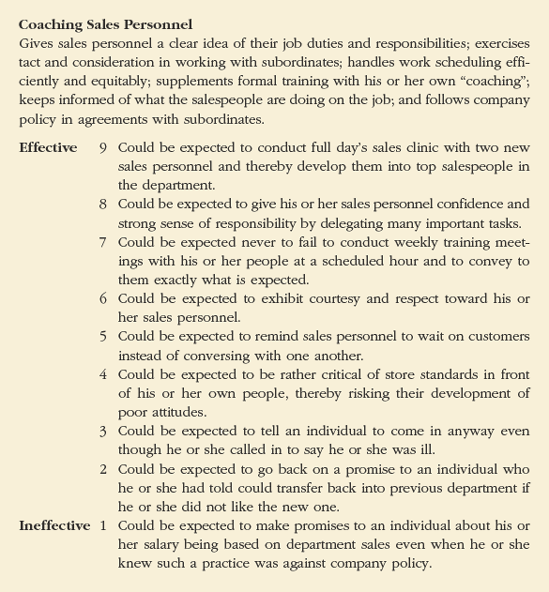

The behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) adds more sophistication by linking ratings to specific and observable job-relevant behaviors. These are typically provided by managers and personnel specialists and include descriptions of superior and inferior performance. Once a large sample of behavioral descriptions has been collected, each behavior is evaluated to determine the extent to which it describes good versus bad performance. The final step is to develop a rating scale in which the anchors are specific critical behaviors, each reflecting a different degree of performance effectiveness.

The behaviorally anchored rating scale links performance ratings to specific and observable job-relevant behaviors.

A sample BARS for a retail department manager is shown in Figure 6.4. Note the specificity of the behaviors and the scale values for each. Similar behaviorally anchored scales would be developed for other dimensions of the job. The BARS approach is detailed and complex, and requires time to develop. But it can provide specific behavioral information that is useful for counseling and feedback, especially when combined with comparative methods just discussed and other methods described next.[334]

Critical Incident Diary Critical incident diaries are written records that give examples of a person's work behavior that leads to either unusual performance success or failure. The incidents are typically recorded in a diary-type log that is kept daily or weekly under predetermined dimensions. In a sales job, for example, following up sales calls and communicating necessary customer information might be two of the dimensions recorded in a critical incident diary. Descriptive paragraphs can then be used to summarize each salesperson's performance for each dimension as activities are observed. This approach is excellent for employee development and feedback. But because the method consists of qualitative statements rather than quantitative ratings, it is more debatable in terms of summative evaluations. This is why we often find the critical incident technique used in combination with one of the other methods.

Figure 6.4. Sample performance appraisal dimension from the behaviorally anchored rating scale for a department store manager.

360° Evaluation To obtain as much appraisal information as possible, many organizations now use a combination of evaluations from a person's bosses, peers, and subordinates, as well as internal and external customers and self-ratings. Such a comprehensive approach is called a 360° evaluation and it is very common now in horizontal and team-oriented organization structures.[335] The 360° evaluation has also moved online with software that both collects and organizes the results of ratings from multiple sources. A typical approach asks the jobholder to do a self rating and then discuss with the boss and perhaps a sample of the 360° participants the implications from both evaluation and counseling perspectives.

A 360° evaluation gathers evaluations from a jobholder's bosses, peers, and subordinates, as well as internal and external customers and self-ratings.

Regardless of the method being employed, any performance appraisal system should meet two criteria: reliability—providing consistent results each time it is used for the same person and situation, and validity—actually measuring people on dimensions with direct relevance to job performance. In addition to the strengths and weaknesses of the methods just discussed, there are a number of measurement errors that can reduce the reliability or validity of performance appraisals.[336]

Halo error—results when one person rates another person on several different dimensions and gives a similar rating for each dimension.

Leniency error—just as some professors are known as "easy A's," some managers tend to give relatively high ratings to virtually everyone under their supervision; the opposite is strictness error—giving everyone a low rating.

Central tendency error—occurs when managers lump everyone together around the average, or middle, category; this gives the impression that there are no very good or very poor performers on the dimensions being rated.

Recency error—occurs when a rater allows recent events to influence a performance rating over earlier events; an example is being critical of an employee who is usually on time but shows up one hour late for work the day before his or her performance rating.

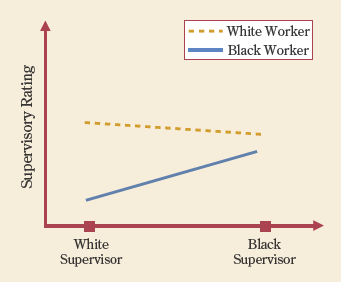

Personal bias error—displays expectations and prejudices that fail to give the jobholder complete respect, such as showing racial bias in ratings.

Reliability means a performance measure gives consistent results.

Validity means a performance measure addresses job-relevant dimensions.

When it comes to motivation we might say that nothing beats a good person-job fit. This means that the job requirements fit well with individual abilities and needs, and that the experience of performing the job under these conditions is likely to be high in intrinsic rewards. By contrast, a poor person-job fit is likely to cause performance problems and be somewhat demotivating for the worker. You might think of the goal this way: Person + Good Job Fit = Intrinsic Motivation.

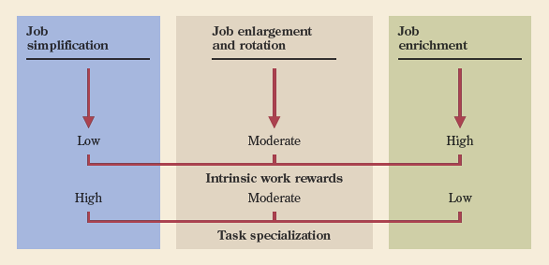

Job design is the process through which managers plan and specify job tasks and the work arrangements that allow them to be accomplished. Figure 6.5 shows three major alternative job design approaches, and it also indicates how they differ in the way required tasks are defined and in the motivation provided for the worker. In this sense, the "best" job design is always one that meets organizational requirements for high performance, offers a good fit with individual skills and needs, and provides valued opportunities for job satisfaction.

Job design is the process of specifying job tasks and work arrangements.

The history of scholarly interest in job design can be traced in part to Frederick Taylor's work with scientific management in the early 1900s.[337] Taylor and his contemporaries wanted to create management and organizational practices that would increase people's efficiency at work. Their approach was to study a job carefully, break it into its smallest components, establish exact time and motion requirements for each task to be done, and then train workers to do these tasks in the same way over and over again. Taylor's principles of scientific management can be summarized as follows:

Taylor's scientific management used systematic study of job components to develop practices to increase people's efficiency at work.

Develop a "science" for each job that covers rules of motion, standard work tools, and supportive work conditions.

Hire workers with the right abilities for the job.

Train and motivate workers to do their jobs according to the science.

Support workers by planning and assisting their work using the job science.

These early efforts were forerunners of current industrial engineering approaches to job design that emphasize efficiency. Such approaches attempt to determine the best processes, methods, workflow layouts, output standards, and person-machine interfaces for various jobs. A good example is found at United Parcel Service (UPS), where calibrated productivity standards carefully guide workers. At regional centers, sorters must load vans at a set number of packages per hour. After analyzing delivery stops on regular van routes, supervisors generally know within a few minutes how long a driver's pickups and deliveries will take. Engineers devise precise routines for drivers, who save time by knocking on customers' doors rather than looking for doorbells. Handheld computers further enhance delivery efficiencies.

Today, the term job simplification is used to describe a scientific management approach to job design that standardizes work procedures and employs people in clearly defined and highly specialized tasks. The machine-paced automobile assembly line is a classic example. Why is it used? Typically, the answer is to increase operating efficiency by reducing the number of skills required to do a job, by being able to hire low-cost labor, by keeping the needs for job training to a minimum, and by emphasizing the accomplishment of repetitive tasks. However, the very nature of such jobs creates potential disadvantages as well. These include loss of efficiency in the face of lower quality, high rates of absenteeism and turnover, and demand for higher wages to compensate for unappealing jobs. One response to such problems is through advanced applications of new technology. In automobile manufacturing, for example, robots now do many different kinds of work previously accomplished with human labor.

In job simplification the number or variety of different tasks performed is limited. Although this makes the tasks easier to master, the repetitiveness can reduce motivation. This result has prompted alternative job design approaches that try to make jobs more interesting by adding breadth to the variety of tasks performed.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining into one job two or more tasks that were previously assigned to separate workers. Sometimes called horizontal loading, this approach increases job breadth by having the worker perform more and different tasks, but all at the same level of responsibility and challenge.

Job rotation, another horizontal-loading approach, increases task variety by periodically shifting workers among jobs involving different tasks. Again, the responsibility level of the tasks stays the same. The rotation can be arranged according to almost any time schedule, such as hourly, daily, or weekly schedules. An important benefit of job rotation is training. It allows workers to become more familiar with different tasks and increases the flexibility with which they can be moved from one job to another.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining into one job two or more tasks that were previously assigned to separate workers.

Job rotation increases task variety by periodically shifting workers among jobs involving different tasks.

A third job design alternative traces back to Frederick Herzberg's two-factor theory of motivation described in Chapter 5. This theory suggests that jobs designed on the basis of simplification, enlargement, or rotation shouldn't be expected to deliver high levels of motivation.[338] "Why," asks Herzberg, "should a worker become motivated when one or more 'meaningless' tasks are added to previously existing ones or when work assignments are rotated among equally 'meaningless' tasks?" He recommends using job enrichment to build high-content jobs full of motivating factors such as responsibility, achievement, recognition, and personal growth. Such jobs include planning and evaluating duties that would otherwise be reserved for managers.

The content changes made possible by job enrichment (see OB Savvy 6.2) involve what Herzberg calls vertical loading to increase job depth. This essentially means that tasks normally performed by supervisors are pulled down into the job to make it bigger. Such enriched jobs, he believes, satisfy higher-order needs and increase motivation to achieve high levels of job performance.

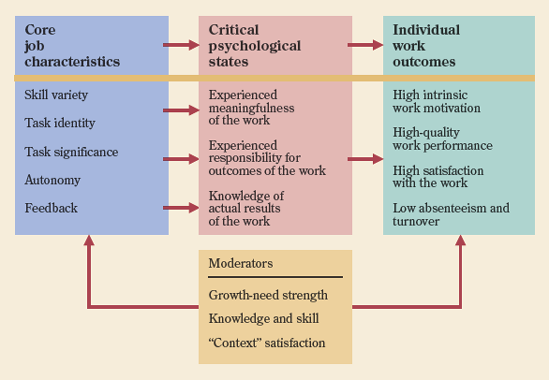

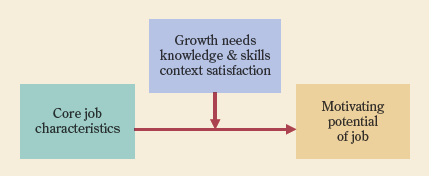

OB scholars have been reluctant to recommend job enrichment as a universal solution to all job performance and satisfaction problems, particularly given the many individual differences that characterize people at work. Their answer to the question "Is job enrichment for everyone?" is a clear "No." Present thinking focuses more on a diagnostic approach to job design developed by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham.[339] Their job characteristics model provides a data-based approach for creating job designs with good person-job fit that maximize the potential for motivation and performance.

Figure 6.6 shows how five core job characteristics activate the model and inform the process of job design. The higher a job scores on each core characteristic, the more it is considered to be enriched.

Skill variety—the degree to which a job includes a variety of different activities and involves the use of a number of different skills and talents

Task identity—the degree to which the job requires completion of a "whole" and identifiable piece of work, one that involves doing a job from beginning to end with a visible outcome

Task significance—the degree to which the job is important and involves a meaningful contribution to the organization or society in general

Autonomy—the degree to which the job gives the employee substantial freedom, independence, and discretion in scheduling the work and determining the procedures used in carrying it out

Job feedback—the degree to which carrying out the work activities provides direct and clear information to the employee regarding how well the job has been done

Job Diagnostic Survey Hackman and Oldham recommend measuring the current status of a job based on each core characteristic.[340] These characteristics can then be changed systematically to enrich the job and increase its motivational potential. This assessment can be accomplished using an instrument called the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS), which is included in the OB Skills Workbook as part of the team and experiential exercise "Job Design." Scores on the JDS are combined to create a motivating potential score, or MPS, which indicates the degree to which the job is capable of motivating people.

A job's MPS can be raised by combining tasks to create larger jobs, opening feedback channels to enable workers to know how well they are doing, establishing client relationships to experience such feedback directly from customers, and employing vertical loading to create more planning and controlling responsibilities. When the core characteristics are enriched in these ways to raise the MPS as high as possible, the redesigned job can be expected to positively influence three critical psychological states: (1) experienced meaningfulness of the work, (2) experienced responsibility for the outcomes of the work, and (3) knowledge of actual results of the work. These positive psychological states, in turn, are supposed to have a positive impact on individual motivation, performance, and satisfaction.

Moderator Variables The job characteristics model recognizes that the five core job characteristics do not affect all people in the same way. Rather than accept Herzberg's implication that enriched jobs should be good for everyone, this approach suggests that enriched jobs will lead to positive outcomes only for those persons who are a good match for them. When the fit between the person and an enriched job is poor, positive outcomes are less likely and problems may well result. "Fit" in the job characteristics model is viewed from the perspective of three moderator variables shown in Figure 6.6 and briefly summarized again here.

The first moderator is growth-need strength, or the degree to which a person desires the opportunity for self-direction, learning, and personal accomplishment at work. It is similar to Abraham Maslow's esteem and self-actualization needs and Alderfer's growth needs, as discussed in Chapter 5. When applied here, the expectation is that people high in growth-need strengths at work will respond positively to enriched jobs, whereas people low in growth-need strengths will find enriched jobs to be sources of anxiety.

The second moderator is knowledge and skill. People whose capabilities fit the demands of enriched jobs are predicted to feel good about them and perform well. Those who are inadequate or who feel inadequate in this regard are likely to experience difficulties.

The third moderator is context satisfaction, or the extent to which an employee is satisfied with aspects of the work setting such as salary levels, quality of supervision, relationships with co-workers, and working conditions. In general, people who are satisfied with job context are more likely to do well with job enrichment.

Research Considerable research has been done on the job characteristics model in a variety of work settings, including banks, correctional institutions, telephone companies, and manufacturing firms, as well as in government agencies. Experts generally agree that the model and its diagnostic approach are useful, but not yet perfect, guides to job design.[341] On average, job characteristics do affect performance but not nearly as much as they do satisfaction. The research also emphasizes the importance of growth-needs strength as a moderator of the job design-job performance-job satisfaction relationships. Positive job characteristics affect performance more strongly for high-growth-need than for low-growth-need individuals. The relationship is about the same with job satisfaction. It is also clear that job enrichment can fail when job requirements are increased beyond the level of individual capabilities or interests.

One note of caution is raised by Gerald Salancik and Jeffrey Pfeffer, who question whether jobs have stable and objective characteristics to which individuals respond predictably and consistently.[342] Instead, they view job design from the perspective of social information processing theory. This theory argues that individual needs, task perceptions, and reactions are a result of socially constructed realities. Social information in organizations influences the way people perceive their jobs and respond to them. The same holds true, for example, in the classroom. Suppose that several of your friends tell you that the instructor for a course is bad, the content is boring, and the requirements involve too much work. You may then think that the critical characteristics of the class are the instructor, the content, and the workload, and that they are all bad. All of this may substantially influence the way you perceive your instructor and the course, and the way you deal with the class—regardless of the actual characteristics.

Finally, research suggests the following answers to common questions about job enrichment and its applications. Should everyone's job be enriched? The answer is clearly no. The logic of individual differences suggests that not everyone will want an enriched job. Individuals most likely to have positive reactions to job enrichment are those who need achievement, who exhibit a strong work ethic, or who are seeking higher-order growth-need satisfaction at work. Job enrichment also appears to be most advantageous when the job context is positive and when workers have the abilities needed to do the enriched job. Furthermore, costs, technological constraints, and workgroup or union opposition may make it difficult to enrich some jobs. Can job enrichment apply to groups? The answer is yes. The application of job-design strategies at the group level is growing in many types of settings. Part 3 discusses creative workgroup designs, including cross-functional work teams and self-managing teams.

New work arrangements are reshaping the traditional 40-hour week, with its 9-to-5 schedules and work done at the company or place of business. Virtually all such plans are designed to influence employee satisfaction and to help employees balance the demands of their work and nonwork lives.[343] They are becoming more and more important in fast-changing societies where demands for "work-life balance" and more "family-friendly" employers are growing ever more apparent. If you have any doubts at all regarding the importance of work-life issues, consider these facts: 78 percent of American couples are dual wage earners; 63 percent believe they don't have enough time for spouses and partners; 74 percent believe they don't have enough time for their children; 35 percent are spending time caring for elderly relatives.24 And, both baby boomers (87 percent) and Gen Ys (89 percent) rate flexible work as important; they also want opportunities to work remotely at least part of the time—Boomers (63 percent) and Gen Ys (69 percent).25

A compressed work week is any scheduling of work that allows a full-time job to be completed in fewer than the standard five days. The most common form of compressed work week is the "4/40," or 40 hours of work accomplished in four 10-hour days.

A compressed work week allows a full-time job to be completed in fewer than the standard five days.

This approach has many possible benefits. For the worker, additional time off is a major feature of this schedule. The individual often appreciates increased leisure time, three-day weekends, free weekdays to pursue personal business, and lower commuting costs. The organization can benefit, too, in terms of lower employee absenteeism and improved recruiting of new employees. But there are also potential disadvantages. Individuals can experience increased fatigue from the extended workday and family adjustment problems.

The organization can experience work scheduling problems and customer complaints because of breaks in work coverage. Some organizations may face occasional union opposition and laws requiring payment of overtime for work exceeding eight hours of individual labor in any one day. Overall reactions to compressed work weeks are likely to be most favorable among employees who are allowed to participate in the decision to adopt the new work week, who have their jobs enriched as a result of the new schedule, and who have the strong higher-order needs identified in Maslow's hierarchy.[344]

Another innovative work schedule, flexible working hours or flextime gives individuals a daily choice in the timing of their work commitments. One such schedule requires employees to work four hours of "core" time but leaves them free to choose their remaining four hours of work from among flexible time blocks. One person, for example, may start early and leave early, whereas another may start later and leave later. This flexible work schedule is becoming increasingly popular and is a valuable alternative for structuring work to accommodate individual interests and needs. All top 100 companies in Working Mother magazine's list of best employers for working moms offer flexible scheduling. Reports indicate that flexibility in dealing with nonwork obligations reduces stress and unwanted job turnover.27

The individual autonomy in work scheduling allowed by flextime can help reduce absenteeism, tardiness, and turnover for the organization, and also contribute to higher levels of organizational commitment and performance by workers. On the individual side it brings potential advantages in terms of commuting times and opportunities to meet personal responsibilities during the work week. It is a way for dual-career couples to handle children's schedules as well as their own; it is a way to meet the demands of caring for elderly parents or ill family members; it is even a way to better attend to such personal affairs as medical and dental appointments, home emergencies, banking needs, and so on. Proponents of this scheduling strategy argue that the discretion it allows workers in scheduling their own hours of work encourages them to develop positive attitudes and to increase commitment to the organization.

In job sharing, one full-time job is assigned to two or more persons who then divide the work according to agreed-upon hours. Often, each person works half a day, but job sharing can also be done on a weekly or monthly basis. Organizations benefit from job sharing when they can attract talented people who would otherwise be unable to work. An example is the qualified teacher who also is a parent. This person may be able to work only half a day. Through job sharing, two such persons can be employed to teach one class. Some job sharers report less burnout and claim that they feel recharged each time they report for work. The tricky part of this arrangement is finding two people who will work well with each other.

In job sharing one full-time job is split between two or more persons who divide the work according to agreed-upon hours.

Job sharing should not be confused with something called work sharing. This occurs when workers agree to cut back on the number of hours they work in order to protect against layoffs. In the recent economic crisis, for example, workers in some organizations agreed to voluntarily reduce their paid hours worked so that others would not lose their jobs. Many employers tried to manage the crisis with an involuntary form of work sharing. An example is Pella Windows which went to a four-day workweek for some 3,900 workers to avoid layoffs.[345]

Technology has enabled yet another alternative work arrangement that is now highly visible in many employment sectors ranging from higher education to government, and from manufacturing to services. Telecommuting is work done at home or in a remote location via the use of computers and advanced telecommunications linkages with a central office or other employment locations. And, it's popular; the number of workers who are telecommuting is growing daily, with corporate telecommuters now numbering at least 9 million.[346]

When asked what they like, telecommuters report increased productivity, fewer distractions, the freedom to be their own boss, and the benefit of having more time for themselves. Potential advantages also include more flexibility, the comforts of home, and the choice of locations consistent with the individual's lifestyle. But there are potential negatives as well. Some telecommuters report working too much while having less time to themselves, difficulty separating work and personal life, and less time for family.30 Other complaints include not being considered important, isolation from co-workers, decreased identification with the work team, and even the interruptions of everyday family affairs. One telecommuter says: "You have to have self-discipline and pride in what you do, but you also have to have a boss that trusts you enough to get out of the way."31

Telecommuting is work done at home or from a remote location using computers and advanced telecommunications.

A recent development is the co-working center, essentially a place where telecommuters go to share an office environment outside of the home and join the company of others. One marketing agency telecommuter says: "we have two kids, so the ability to work from home—it just got worse and worse. I found myself saying, 'If daddy could just have two hours....'" Now he has started his own co-working center to cater to his needs and those of others. One of those using his center says: "What you're paying for is not the desk, it's access to networking, creativity and community."[347]

Part-time work has become an increasingly prominent and controversial work arrangement. In temporary part-time work an employee works only when needed and for less than the standard 40-hour work week. Some choose this part-time schedule because they like it. But others are involuntary part-timers that would prefer a full-time work schedule but do not have access to one. Someone doing permanent part-time work is considered a "permanent" member of the workforce although still working fewer hours than the standard 40-hour week. Called permatemps, these workers are regularly employed but not given access to health insurance, pension, and other fringe benefits. Their situations fall into a murky area under the law and is attracting more public attention, including that of labor unions.

A part-time work schedule can be a benefit to people who want to supplement other jobs or who want something less than a full work week for a variety of personal reasons. But there are downsides. When a person holds multiple part-time jobs, the work burdens can be stressful; performance may suffer on the job, and spillover effects to family and leisure time can be negative. Also, part-timers often fail to qualify for fringe benefits such as health care insurance and retirement plans. And they may be paid less than their full-time counterparts.

Many employers use part-time work to hold down labor costs and to help smooth out peaks and valleys in the business cycle. Temporary part-timers are easily released and hired as needs dictate; during difficult business times they will most likely be laid off before full-timers. In today's economy the use of part-timers is growing as employers try to cut back labor costs; in just one year the number of involuntary part-time workers grew from 4.5 million to 9 million.[348]

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 6.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 6 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What is the link between motivation, performance, and rewards?

The integrated model of motivation brings together insights from content, process, and learning theories around the basic effort → performance → reward linkage.

Reward systems emphasize a mix of intrinsic rewards—such as a sense of achievement from completing a challenging task, and extrinsic rewards—such as receiving a pay increase.

Pay for performance systems take a variety of forms, including merit pay, gain-sharing and profit-sharing plans, lump-sum increases, and employee stock ownership.

Pay for skills is an increasingly common practice; flexible benefits plans are also increasingly common as the role of benefits as part of an employee's total compensation package gains in motivational importance.

What are the essentials of performance management?

Performance management is the process of managing performance measurement and the variety of human resource decisions associated with such measurement.

Performance measurement serves both an evaluative purpose for reward allocation and a development purpose for future performance improvement.

Performance measurement can be done using output measures of performance accomplishment or activity measures of performance efforts.

The ranking, paired comparison, and forced-distribution approaches are examples of comparative performance appraisal methods.

The graphic rating scale and behaviorally anchored rating scale use individual ratings on personal and performance characteristics to appraise performance.

360° appraisals involve the full circle of contacts a person may have in job performance—from bosses, to peers, to subordinates, to internal and external customers.

Common measurement errors in performance appraisal include halo errors, central tendency errors, recency errors, personal bias errors, and cultural bias errors.

How do job designs influence motivation?

Job design by scientific management or job simplification standardizes work and employs people in clearly defined and specialized tasks.

Job enlargement increases task variety by combining two or more tasks previously assigned to separate workers; job rotation increases task variety by periodically rotating workers among jobs involving different tasks; job enrichment builds bigger and more responsible jobs by adding planning and evaluating duties.

Job characteristics theory offers a diagnostic approach to job enrichment based on analysis of five core job characteristics: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback.

Job characteristics theory does not assume that everyone wants an enriched job; it indicates that job enrichment will be more successful for persons with high growth needs, requisite job skills, and context satisfaction.

What are the motivational opportunities of alternative work schedules?

Today's complex society is giving rise to a number of alternative work arrangements designed to balance the personal demands on workers with job responsibilities and opportunities.

The compressed work week allows a full-time work week to be completed in fewer than five days, typically offering four 10-hour days of work and three days free.

Flexible working hours allow employees some daily choice in timing between work and nonwork activities.

Job sharing occurs when two or more people divide one full-time job according to agreements among themselves and the employer.

Telecommuting involves work at home or at a remote location while communicating with the home office as needed via computer and related technologies.

Part-time work requires less than a 40-hour work week and can be done on a schedule classifying the worker as temporary or permanent.

Activity measures (p. 136)

Behaviorally anchored rating scale (p. 137)

Compressed work week (p. 146)

Critical incident diaries (p. 137)

Employee stock ownership plans (p. 134)

Extrinsic rewards (p. 131)

Flexible working hours (p. 146)

Forced distribution (p. 136)

Gain sharing (p. 133)

Graphic rating scales (p. 136)

Intrinsic rewards (p. 131)

Job design (p. 139)

Job enlargement (p. 142)

Job enrichment (p. 142)

Job rotation (p. 142)

Job sharing (p. 147)

Job simplification (p. 141)

Merit pay (p. 133)

Motivation (p. 130)

Output measures (p. 136)

Paired comparison (p. 136)

Performance-contingent pay (p. 132)

Profit sharing (p. 133)

Ranking (p. 136)

Reliability (p. 139)

Scientific management (p. 140)

Skill-based pay (p. 134)

Stock options (p. 134)

Telecommuting (p. 148)

360° evaluation (p. 138)

Validity (p. 139)

Work sharing (p. 147)

In the integrated model of motivation, what predicts effort? (a) rewards (b) organizational support (c) ability (d) motivation

Pay is generally considered a/an ____________ reward, while a sense of personal growth experienced from working at a task is an example of a/an ____________ reward. (a) extrinsic, skill-based (b) skill-based, intrinsic (c) extrinsic, intrinsic (d) absolute, comparative

If someone improves productivity by developing a new work process and receives a portion of the productivity savings as a monetary reward, this is an example of a/an ____________ plan. (a) cost sharing (b) gain sharing (c) ESOP (d) pay-for-skills

Performance measurement serves two broad purposes: evaluation and ____________. (a) reward allocation (b) counseling (c) discipline (d) benefits calculations

Which form of performance appraisal is an example of the comparative approach? (a) forced distribution (b) graphic rating scale (c) BARS (d) critical incident diary

If a performance appraisal method fails to accurately measure a person's performance on actual job content, it lacks ____________. (a) performance contingency (b) leniency (c) validity (d) strictness

A written record that describes in detail various examples of a person's positive and negative work behaviors is most likely part of which performance appraisal method? (a) forced distribution (b) critical incident diary (c) paired comparison (d) graphic rating scale

When a team leader evaluates the performance of all team members as "average," the possibility for ____________ error in the performance appraisal is quite high. (a) personal bias (b) recency (c) halo (d) central tendency

Job simplification is closely associated with ____________ as originally developed by Frederick Taylor. (a) vertical loading (b) horizontal loading (c) scientific management (d) self-efficacy

Job ____________ increases job ____________ by combining into one job several tasks of similar difficulty. (a) rotation, depth (b) enlargement, depth (c) rotation, breadth (d) enlargement, breadth

If a manager redesigns a job through vertical loading, she would most likely ____________. (a) bring tasks from earlier in the workflow into the job (b) bring tasks from later in the workflow into the job (c) bring higher level or managerial responsibilities into the job (d) raise the standards for high performance

In the job characteristics model, a person will be most likely to find an enriched job motivating if they ____________. (a) receive stock options (b) have ability and support (c) are unhappy with job context (d) have strong growth needs

In the job characteristics model, ____________ indicates the degree to which an individual is able to make decisions affecting his or her work. (a) task variety (b) task identity (c) task significance (d) autonomy

When a job allows a person to do a complete unit of work, for example, process an insurance claim from point of receipt from the customer to the point of final resolution with the customer, it would be considered high on which core characteristic? (a) task identity (b) task significance (c) task autonomy (d) feedback

The "4/40" is a type of ____________ work arrangement. (a) compressed workweek (b) "allow workers to change machine configurations to make different products" (c) job-sharing (d) permanent part-time

Explain how a 360° evaluation works as a performance appraisal approach.

Explain the difference between halo errors and recency errors in performance appraisal.

What role does growth-need strength play in the job characteristics model?

What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of a compressed work week?